Pope County is a county in the U.S. state of Arkansas. As of the 2020 census, the population was 63,381. The county seat is Russellville. The county was formed on November 2, 1829, from a portion of Crawford County and named for John Pope, the third governor of the Arkansas Territory. Pope County was the nineteenth (of seventy-five) county formed. The county’s borders changed eighteen times in the 19th century with the creation of new counties and adjustments between counties. The current boundaries were set on 8 March 1877.

Pope County is geographically diverse, with the Arkansas River Valley and its farmlands and towns in the southern portion and the Ozarks covering nearly two-thirds of the county to the north, including a portion of the rugged Boston Mountains, a deeply dissected plateau. Approximately 40% of the county is in the Ozark National Forest.

Pope County is an alcohol prohibition or dry county.

Pope County is part of the Russellville, Arkansas, Micropolitan Statistical Area which encompasses all of Pope and Yell County.

| Name: | Pope County |

|---|---|

| FIPS code: | 05-115 |

| State: | Arkansas |

| Founded: | November 2, 1829 |

| Named for: | John Pope |

| Seat: | Russellville |

| Largest city: | Russellville |

| Total Area: | 831 sq mi (2,150 km²) |

| Land Area: | 813 sq mi (2,110 km²) |

| Total Population: | 63,381 |

| Population Density: | 76/sq mi (29/km²) |

| Time zone: | UTC−6 (Central) |

| Summer Time Zone (DST): | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Website: | www.popecountyar.com |

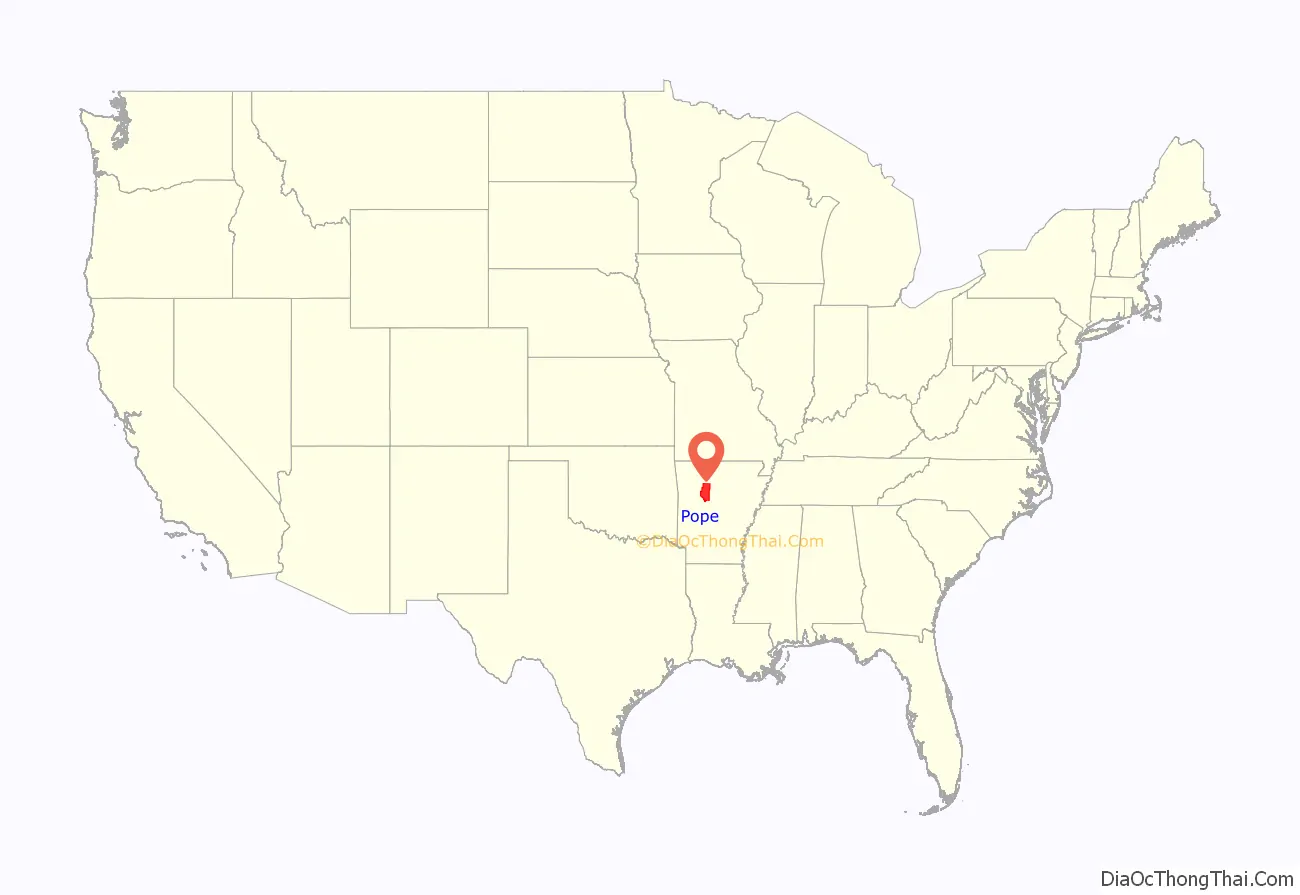

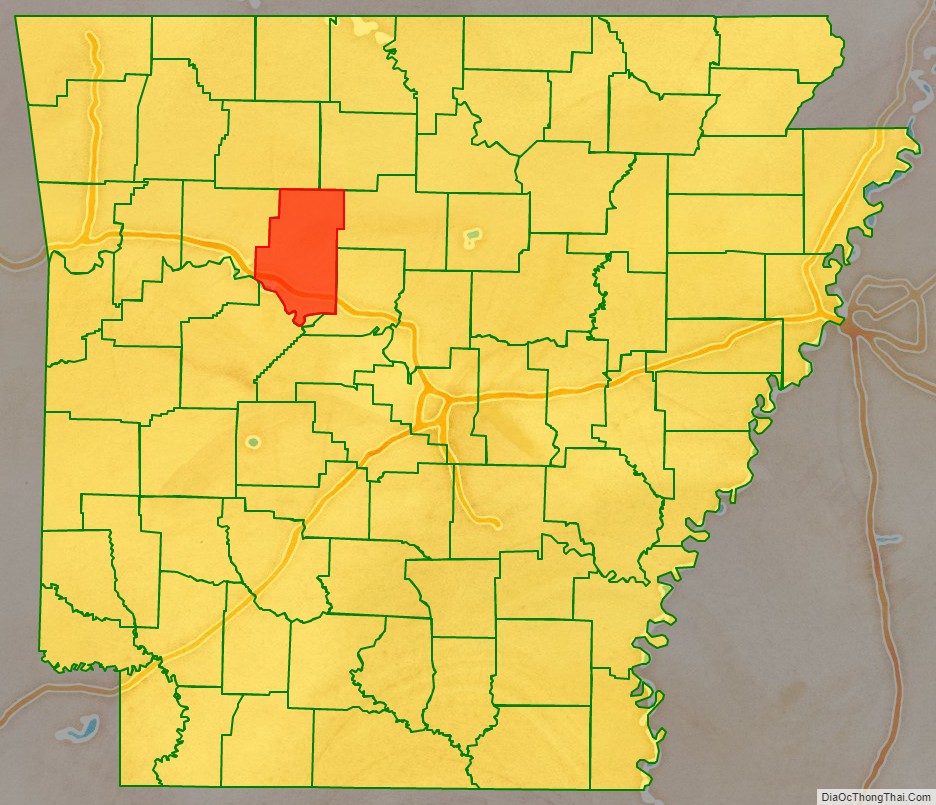

Pope County location map. Where is Pope County?

History

Louisiana Purchase and Cherokee Lands

In 1803, Napoleon Bonaparte sold French Louisiana to the United States, including all of Arkansas. Today, that transaction is known as the Louisiana Purchase.

By 1804, Present Jefferson, with others, looked to the new lands as a refuge for Indian peoples on lands near American settlements, keeping American settlers and Indian societies separate.

Soon after the Louisiana Purchase, much of the region encompassing future Pope and other counties was designated as lands for the removal of eastern native tribes. In about 1805, Cherokee living in southeast Missouri on the Mississippi River moved to the Arkansas River at the suggestion of Louisiana Territory Governor James Wilkinson. After the New Madrid earthquakes, most of the Cherokee—as many as 2,000 people—who had lived along the St. Francis River relocated to the Arkansas River Valley.

In 1815, the US government established a Cherokee Reservation in the Arkansas district of the Missouri Territory and tried to convince the Cherokee to move there voluntarily. The reservation boundaries extended from north of the Arkansas River to the southern bank of the White River. The Cherokee who moved to this reservation became known as the “Old Settlers” or Western Cherokee.

A village on the Illinois Bayou served as the capitol of the Western Cherokees from 1813 to 1824.

The Treaty of 1817 secured lands in Arkansas for the Western Cherokees north of the Arkansas River between Point Remove and Fort Smith. Most white settlers moved to new locations south of the river. By 1820, new Cherokee emigrants from the east had blended with the Old Settlers in a new “colony” with a string of Cherokee villages stretching for over 70 miles above Point Remove. About half of this distance was in the future Pope County. An 1820 description by Territorial Governor James Miller called it a “lovely, rich part of the country.”

In 1818, the chief of the Arkansas Cherokees, Tol-on-tus-ky (Tolunskee or Tollontiskee), requested that the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions send a mission to Arkansas. The assignment was given to Cephas Washburn and his brother-in-law, Alfred Finney, who established a mission in 1820 on the west side of Illinois Bayou about four miles from the Arkansas River. The stream was navigable for keelboats about nine months of the year. The mission was named Dwight for the late Rev. Timothy Dwight, president of Yale College and a corporate member of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. The site was on a gentle rise covered with a growth of oak and pine at the foot of which issued a large spring of pure water. Above, below and opposite the site was plenty of excellent bottomland for cultivation. The mission was conveniently near Indian villages. The mission eventually included more than 25 buildings, including seven log cabins, a dining hall, library, post office, lumber house, carpenter shop, saw mill, meat house, grist mill and barn. The land where Dwight Mission buildings were is now under the waters of Lake Dardanelle, but the cemetery is still on the hill nearby.

By the time Arkansas Territory was established in 1819, the western Cherokees represented at least 20 percent of the total population of the Territory, mostly centered along the Arkansas River and the future Pope County.

Arkansas Territory

Beginning in the 1820s, an increasing number of settlers came to Arkansas from southern states resulting in an environment for the eastern Indians who had moved to Arkansas that was similar to that from which they had been expelled. Under a new treaty concluded on May 6, 1828, the western boundary of Arkansas was established with seven million acres to the west of that provided to the Cherokees “forever.” The Cherokees agreed to leave the Arkansas lands within 14 months. In 1829, all of the people at Dwight Mission moved to the new Indian Territory—in present-day Oklahoma—, where Dwight Mission was re-established in a new location.

Pope County was established on November 2, 1829, ten years after the establishment of the Territory of Arkansas, with a temporary county seat to be at the home of John Bollinger. A county seat selection commission elected in January 1830 chose the community of Scotia, home of Judge Andrew Scott, a neighbor of Bollinger, as the permanent county seat. With the formation of Johnson County in 1833, Scotia was but half a mile from the county line. The county seat was moved to Dwight and, then, in 1834, to Norristown, a growing town of the Arkansas River upstream and across the river from Dardanelle.

Transportation into Arkansas’ interior in the early years was mostly limited to river travel. While navigable, the Arkansas River was unpredictable, alternating between floods and droughts and infested with sandbars and snags. The winding Arkansas River passed through a vast swampy floodplain that covered much of eastern Arkansas, a breeding ground for malaria-bearing mosquitos. Settlers in those areas soon suffered from malarial fevers and other ailments and Arkansas gained a reputation as a sick and swampy land. Most pioneers avoided Arkansas and chose other destinations to settle in. Those who ventured further—into central and western parts of the territory, and Pope County—found good soils along the river valley and, in the mountains, healthy forests of pine, oaks, and hickory, with well-drained soils for farming in the valleys, a wealth of forage for grazing and an abundance of game animals. At the end of the territorial years, the bulk of the people of Pope County were plain-folk farmers, herders, and hunters.

Antebellum Pope County

After Arkansas became a state on June 15, 1836, the county seat was moved to Dover in 1841 after being selected by commissioners chosen for that purpose. The first courthouse was a log structure.

With the outbreak of war with Mexico, in July 1846, a company of mounted infantry volunteers from Pope County, organized under Captain David West, along with volunteer units from other counties, entered service in the Indian Territory, replacing regular Army troops that had been dispatched to Mexico. The Arkansas volunteer troops provided an essential Federal military presence along the state’s western border and eastern portion of the Indian Territory during a period of violent disputes between factions in the Cherokee Nation. After the arrival of three companies of regular Army dragoon recruits, the Pope County volunteers returned home in late April 1847.

There were 695 white families in Pope County in 1850. The total population, according to the census, was 4,710. Only 1,640 had been born in Arkansas. Most of the rest had been born in southern slave states. There were 11 who were foreign-born, including Dr. Thomas Russell. Sixty-two percent of the white population was under 15 years old. Twenty-three individuals were seventy or older; just two had made it to eighty. Over eighty percent of the population was supported by agriculture, mostly by self-sufficient farm families. Other occupations included carpentry, blacksmithing, tanning, lumbering, merchandising, and wagon-making. There were some lawyers, teachers, doctors, and preachers as well as millers, saddlers, shoemakers, cabinet-makers, county officials, and at least one tar kiln operator. There were only 100 slaveowners, and only ten owned ten or more slaves. Only three farmers had twenty or more slaves, enough to be considered “planters” in the slave culture of the south. There were no free blacks documented. There were thirteen sawmills—two steam-powered and the rest powered by water—, two tanneries, and a cotton factory producing 22,500 pounds of thread annually. Dr. Thomas Russell, for whom Russellville was named, owned 680 acres of land, four slaves, a store, and ten town lots. There were eleven one-teacher subscription schools with a total enrollment of 326 students. Churches totaled ten, according to the census, with 6 Methodist, 2 Baptist, 1 Cumberland Presbyterian, and 1 Old School Presbyterian. Principal causes of death, were, in order, croup, winter fever, cholera, hives, diarrhea, consumption and accidents. More than half of all deaths were infants under one year of age and only nine percent were over forty.

In the late 1850s, Edward Payson Washburn took inspiration from Pope County scenes near the family’s Norristown home for his most famous work, The Arkansas Traveller, the composition of which was derived from a story he heard from Colonel Sandford C. Faulkner. Supposedly occurring on the campaign trail in Arkansas in 1840, Colonel Faulkner’s humorous story ends with a fiddle playing squatter being won over by the traveler (man on horse in image). Washburn’s father was Cephas Washburn, founder of Dwight Mission.

While the majority of the population of Pope County consisted of rural families, many were squatters on state or federal land. In 1851, about 76% of households did not own land and, in 1860, some 66% did not.

In 1860, though its population had grown by 67.4% in a decade, Pope County was still sparsely settled. Along with the rest of Arkansas, it was on an economic frontier attracting relatively large numbers of new settlers, mostly from other southern states. Even though Arkansas had been a state since 1836, the few communities were small with limited development. The population in the 1860 census included 6,905 whites. There were 978 slaves, mostly in the agricultural areas in the southern part of the county. Most families were in the southern lowlands of the county. A railroad being developed to be built through the county—the Little Rock & Fort Smith—was to include a depot in Dover.

Civil War

After South Carolina seceded in December 1860, an election was scheduled in Arkansas for February 1861 to vote on whether Arkansas would secede and if a secession convention would be called. In Pope County, prior to the election, secession was rejected four to one in a straw ballot. In the statewide vote on February 18, secession was voted down. The convention in March rejected an ordinance of secession, scheduled a vote of the people on secession for August, and adjourned subject to recall by the president of the convention. After Confederate guns fired on Fort Sumter and President Lincoln issued a call for support from the states, many advocated for recalling the convention, but others were opposed, such as the delegate from Pope County, William Stout, who wrote, “I believe it is the President’s duty to put down rebellion. I have always thought so.”

Convention President David Walker issued a proclamation calling for the convention to reconvene on May 6 where, in the final vote,the Arkansas Ordinance of Secession was passed by a vote of 69 to 1.

In 1861, much of Pope County was still a wilderness frontier. There was no railroad. Roads were little more than tracks and there were no bridges crossing streams. The population was sparse with most dependent on subsistence farming. Many were squatters not owning the land their cabins were on.

During the war, what little civil authority there was collapsed throughout Arkansas. By 1863, in most of the state, travel was dangerous, farming hazardous, and county government inoperative. Pope County records at Dover were moved to a cave for protection. Several skirmishes took place in the county, but there were no major engagements. On April 8, 1865, Dover, including the courthouse was burned.

The civil war’s primary principles—for the South, independence and preservation of slavery, and for the North, restoration of the Union—soon lost their relevance in thinly settled Pope County. As in much of the region, the already hard lives of much of the population were disrupted by wartime loyalties separating unionists from rebels. For many, the struggle turned into a no-holds-barred conflict of killing and driving out opponents in the interest of ensuring the survival of families and allies. Of those who were able to, many fled to safer places. Most able-bodied men were away from home on one side or the other. Many of those left behind—women, old men, and children—fell prey to bands of guerrillas aligned to the Confederacy—called bushwhackers by Union sympathizers—or the Union—called jayhawkers by southerners. Some belonged to neither side, attacking both sides and committing murder and arson and “pilfering and robbing of clothes, rustling cattle, emptying corn bins, taking whatever they wanted.” Others actively supported one side or the other, such as William Stout’s cooperation with the federals, though it probably led to his assassination in 1865.

With Federal troops stationed at Lewisburg—on the river south of present-day Morrilton—and Clarksville in 1864, foraging parties seeking supplies ranged into Pope County. Many families remaining in the county suffered incursions by the military and guerilla bands.

Following the civil war, Pope County remained sparsely settled, with a census population in 1870 of only 503 more people than had been recorded before the war. Many of the people who had fled the upheaval and uncertainties of the war years never returned and, of course, many former residents had not survived the conflict. The Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad had been postponed by the conflict with the first rails not laid until 1869.

Reconstruction

Even though, in June 1868, Arkansas became the second former Confederate state to be fully restored to the Union, political and social stability was still years away. During the military reconstruction period (1867-1868), when Arkansas was placed in the Fourth Military District, companies E and G of the Nineteenth Infantry, were stationed in Pope County and headquartered at Dover for a year and a half. In 1868, a militia law passed by the general assembly authorized the governor to enroll a state guard modeled, generally, after the U. S. Army. Elements of this guard would be used four years later in Pope County.

Between 1865 and 1870, at least five county officials were assassinated: Sheriff Archibald D. Napier and Deputy Sheriff Albert Parks on October 24, 1865, County Clerk William Stout on December 4, 1865, Sheriff W. Morris Williams on August 20, 1866, and Russellville Postmaster John L. Harkey on July 27, 1868. Napier and Williams both served as Captain of the Third Arkansas Cavalry Regiment (Union), Company I where Wallace H. Hickox, Stout’s successor, was a lieutenant and John H. Williams, a successor to Parks and Morris Williams’ brother, was a bugler.

On March 1, 1870, the new Pope County jail in Dover was burned. A man named Glover later claimed responsibility.

A period of a little over seven months in 1872 and 1873 came to be known as the Pope County Militia War. However, there were no battles or skirmishes. There were no engagements between organized opponents of any kind. Instead, an unofficial militia, headed by four county officers, exerted excessive and harsh control over the county, including threats to burn Dover, the county seat. By the end of the period, three of the four officials were dead.

Late Nineteenth Century

By June 1873, regular service on the Little Rock & Fort Smith Railroad extended all the way through the county as far as Clarksville in Johnson County. County commerce that had previously made Dover the business center of the county moved to Russellville or Atkins.

After several attempts, the county seat was moved from Dover to Russellville in 1887. An act to move the county seat passed in the General Assembly in 1873 but was repealed during a special session of the General Assembly in 1874. On March 19, 1887, an election was held on whether to move the county seat to Russellville or to Atkins. Russellville was selected by a margin of 128 votes out of 2,670 total votes cast. The question on moving the county seat had also gone to the voters nearly a decade earlier on September 2, 1878, but the results were overturned in the courts.

With the completion of the railroad through the county and the move of the county seat, some smaller communities such as Norristown and Dover went into a period of decline or disappeared.

On August 15, 1893, train operations began on the Dardanelle and Russellville Railroad (D&R). A 4.8-mile (7.7 km) shortline that still exists, the D&R railroad runs from Russellville to the north bank of the Arkansas River at North Dardanelle, across from Dardanelle, Arkansas. The line was originally built primarily to transport agricultural products—primarily cotton—from Dardanelle to the LR&FS depot in Russellville. For the first eight years of operation, freight and passengers crossed the river on a ferry.

In 1891, the ferry across the river at Dardanelle was supplanted by the Dardanelle pontoon bridge which was in use for nearly four decades except for periods when its operation was interrupted because of high river flows or other disruptions.

Twentieth Century

On the night of January 16, 1906, nearly half of the business district of Russellville was destroyed by fire. The county courthouse was spared, though most of the buildings in its block of the city were lost.

In 1931, the 1878 county courthouse was demolished and replaced with the current building.

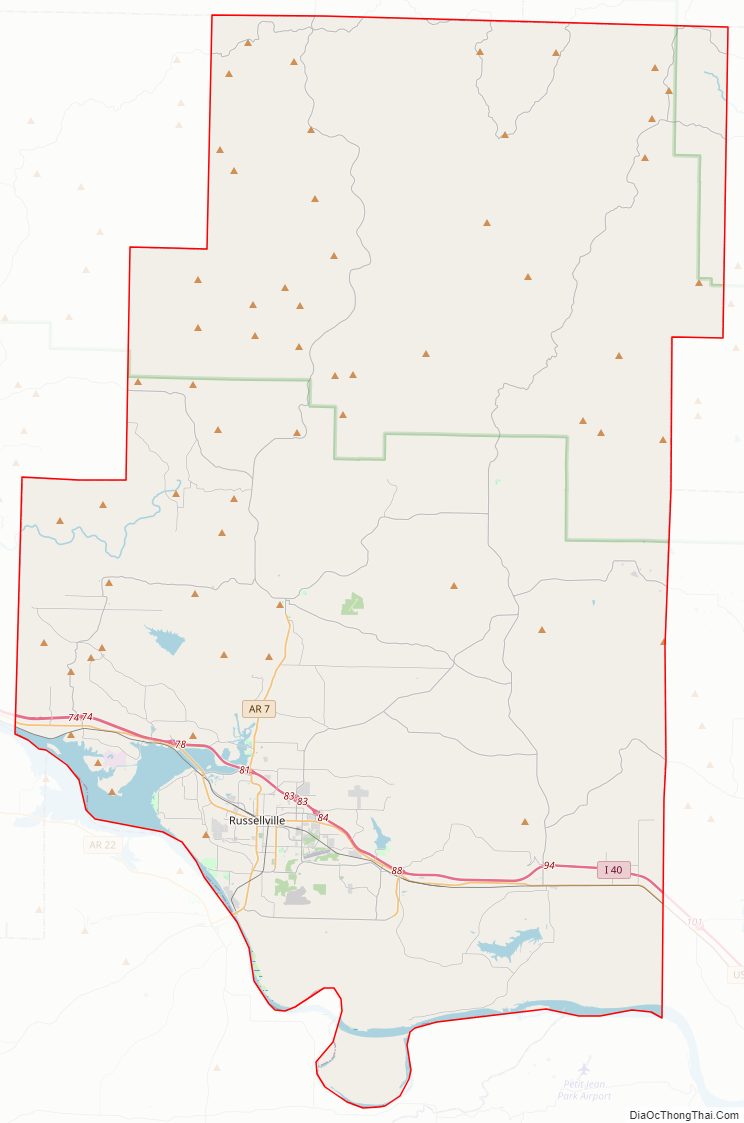

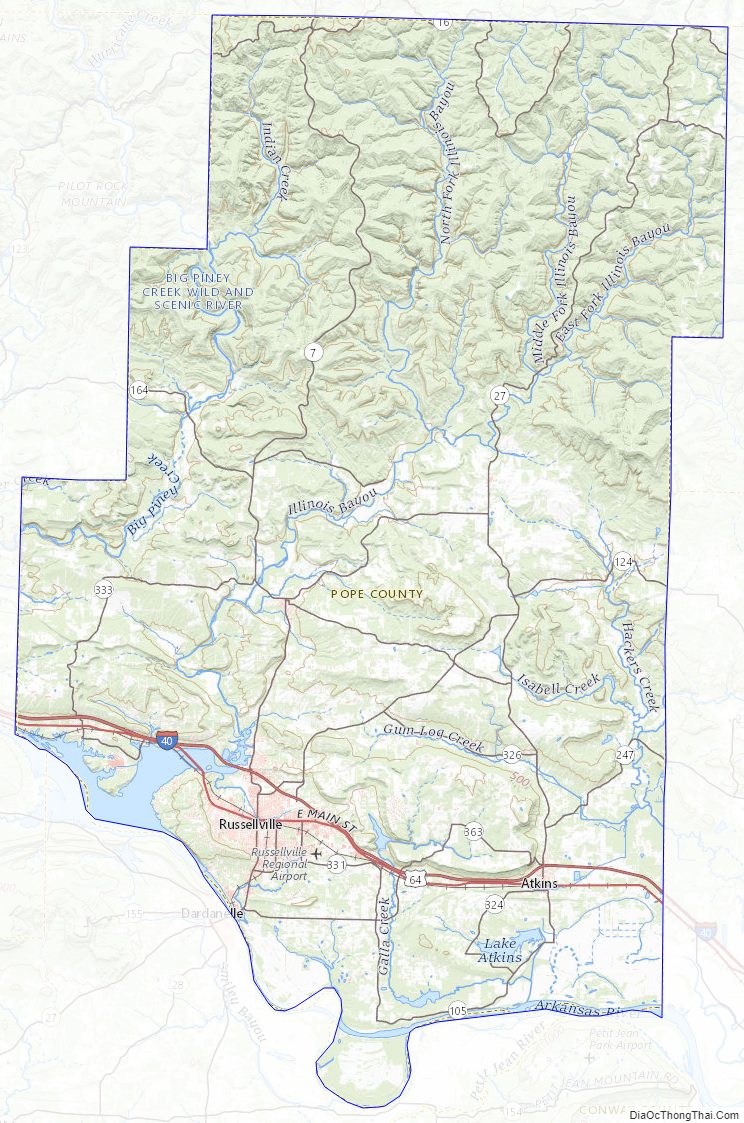

Pope County Road Map

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 831 square miles (2,150 km), of which 813 square miles (2,110 km) is land and 18 square miles (47 km) (2.2%) is water.

Major highways

- Interstate 40

- U.S. Highway 64

- Arkansas Highway 7

- Arkansas Highway 7S

- Arkansas Highway 7T

- Arkansas Highway 16

- Arkansas Highway 27

- Arkansas Highway 105

- Arkansas Highway 123

- Arkansas Highway 124

- Arkansas Highway 164

- Arkansas Highway 247

- Arkansas Highway 324

- Arkansas Highway 326

- Arkansas Highway 331

- Arkansas Highway 333

- Arkansas Highway 363

- Arkansas Highway 980

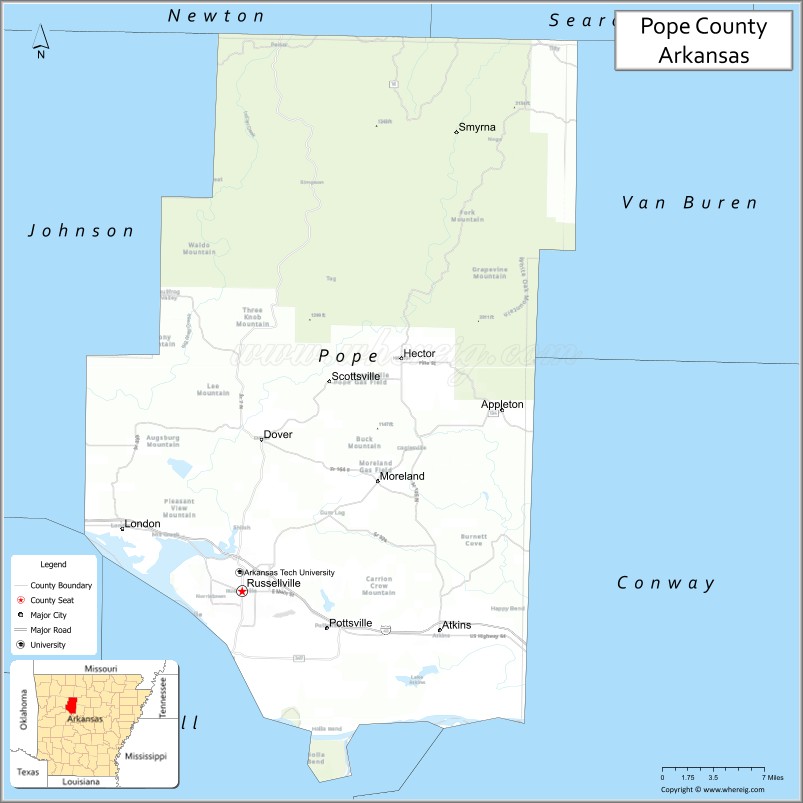

Adjacent counties

- Newton County (northwest)

- Searcy County (northeast)

- Van Buren County (northeast)

- Conway County (southeast)

- Yell County (south)

- Logan County (southwest)

- Johnson County (west)

National protected areas

- Holla Bend National Wildlife Refuge (part)

- Ozark National Forest (part)

- East Fork Wilderness

Pope County Topographic Map

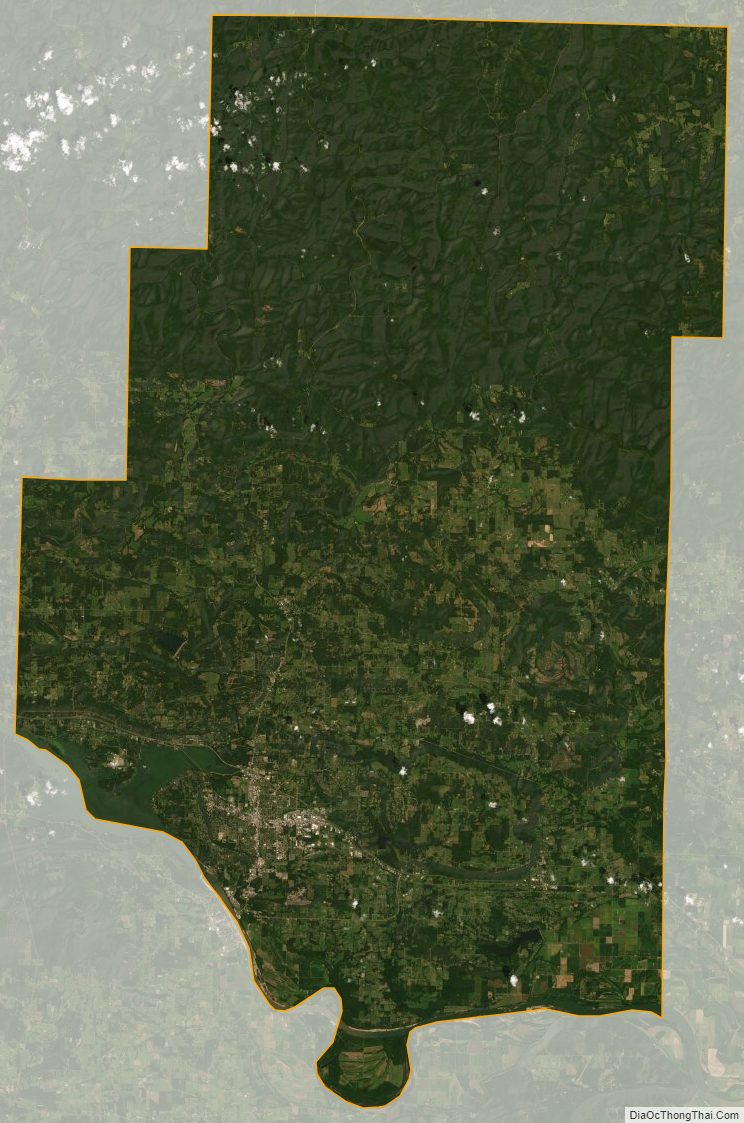

Pope County Satellite Map

Pope County Outline Map

See also

Map of Arkansas State and its subdivision:- Arkansas

- Ashley

- Baxter

- Benton

- Boone

- Bradley

- Calhoun

- Carroll

- Chicot

- Clark

- Clay

- Cleburne

- Cleveland

- Columbia

- Conway

- Craighead

- Crawford

- Crittenden

- Cross

- Dallas

- Desha

- Drew

- Faulkner

- Franklin

- Fulton

- Garland

- Grant

- Greene

- Hempstead

- Hot Spring

- Howard

- Independence

- Izard

- Jackson

- Jefferson

- Johnson

- Lafayette

- Lawrence

- Lee

- Lincoln

- Little River

- Logan

- Lonoke

- Madison

- Marion

- Miller

- Mississippi

- Monroe

- Montgomery

- Nevada

- Newton

- Ouachita

- Perry

- Phillips

- Pike

- Poinsett

- Polk

- Pope

- Prairie

- Pulaski

- Randolph

- Saint Francis

- Saline

- Scott

- Searcy

- Sebastian

- Sevier

- Sharp

- Stone

- Union

- Van Buren

- Washington

- White

- Woodruff

- Yell

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming