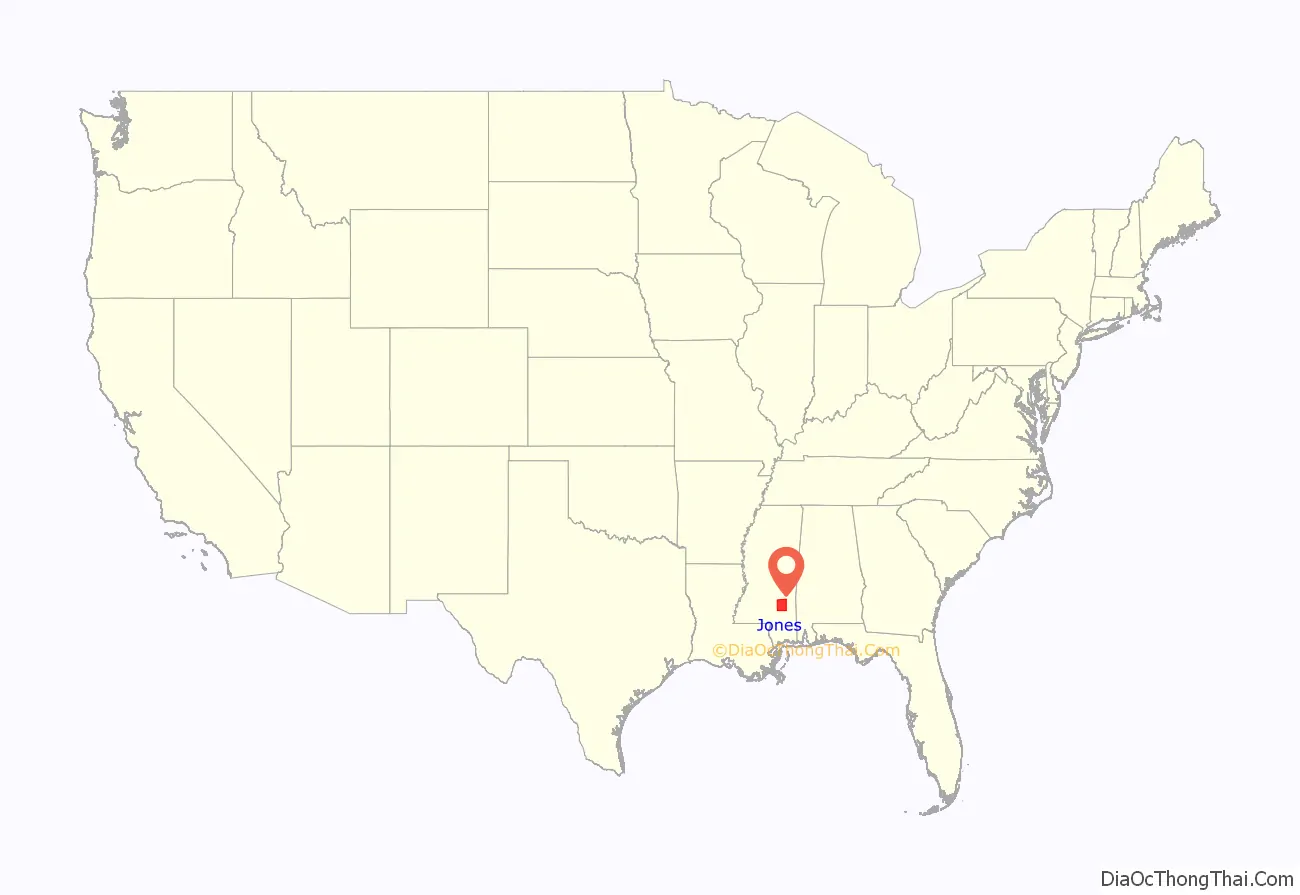

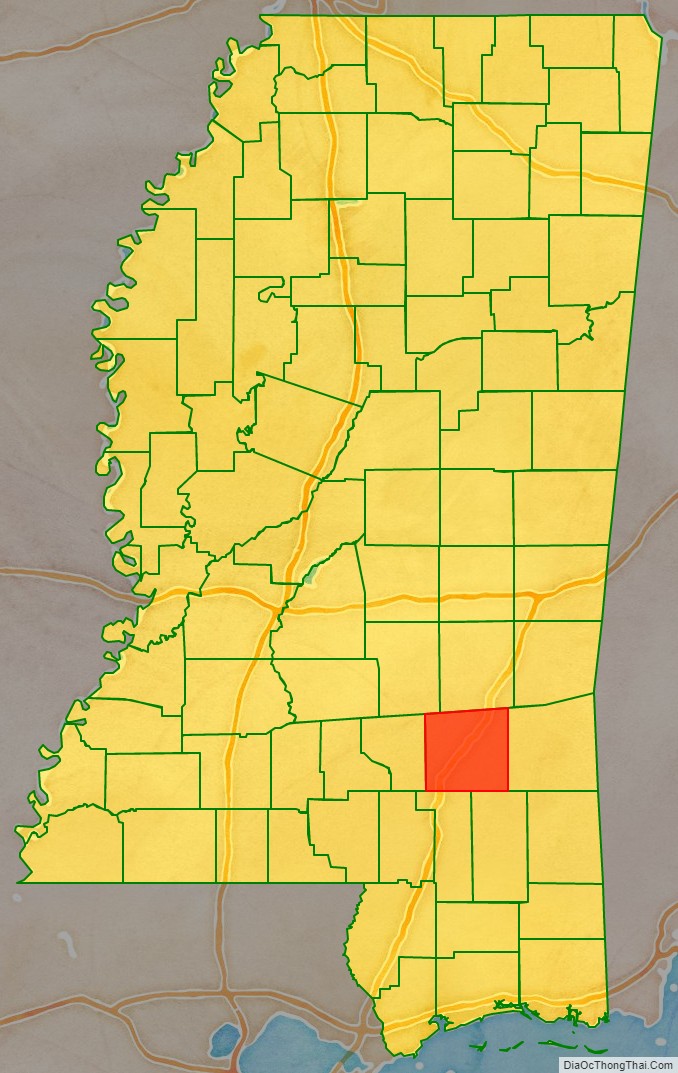

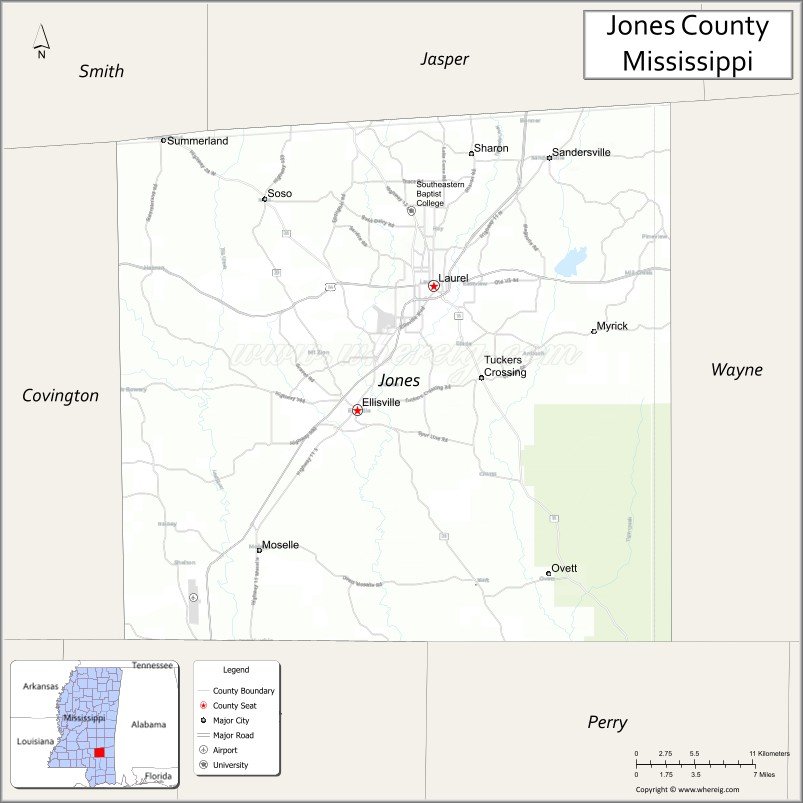

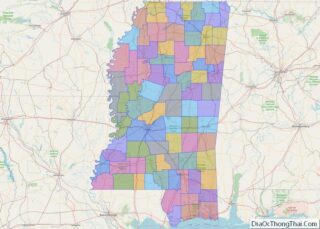

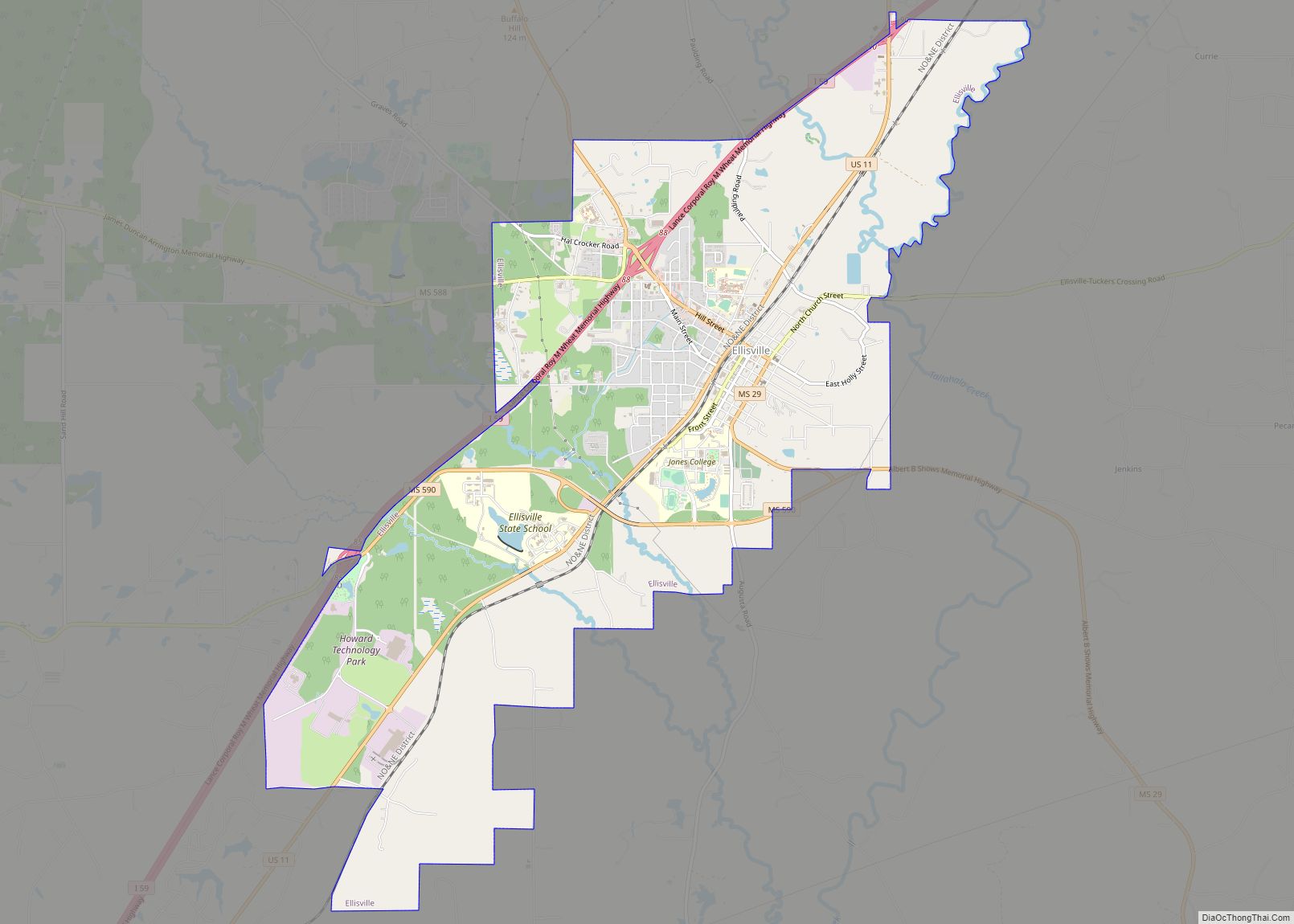

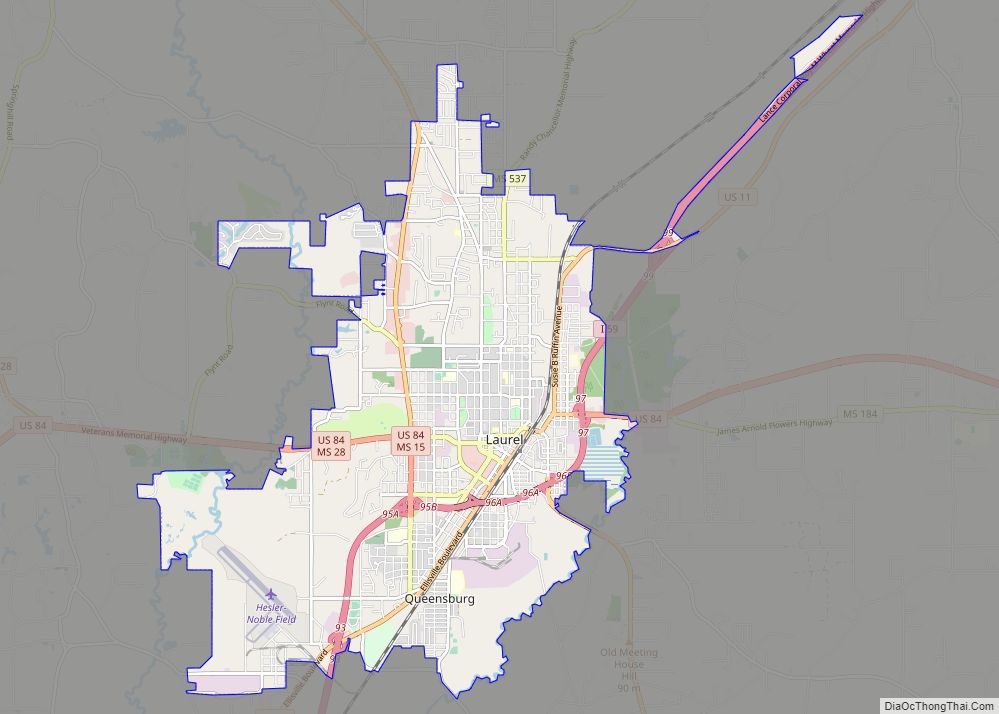

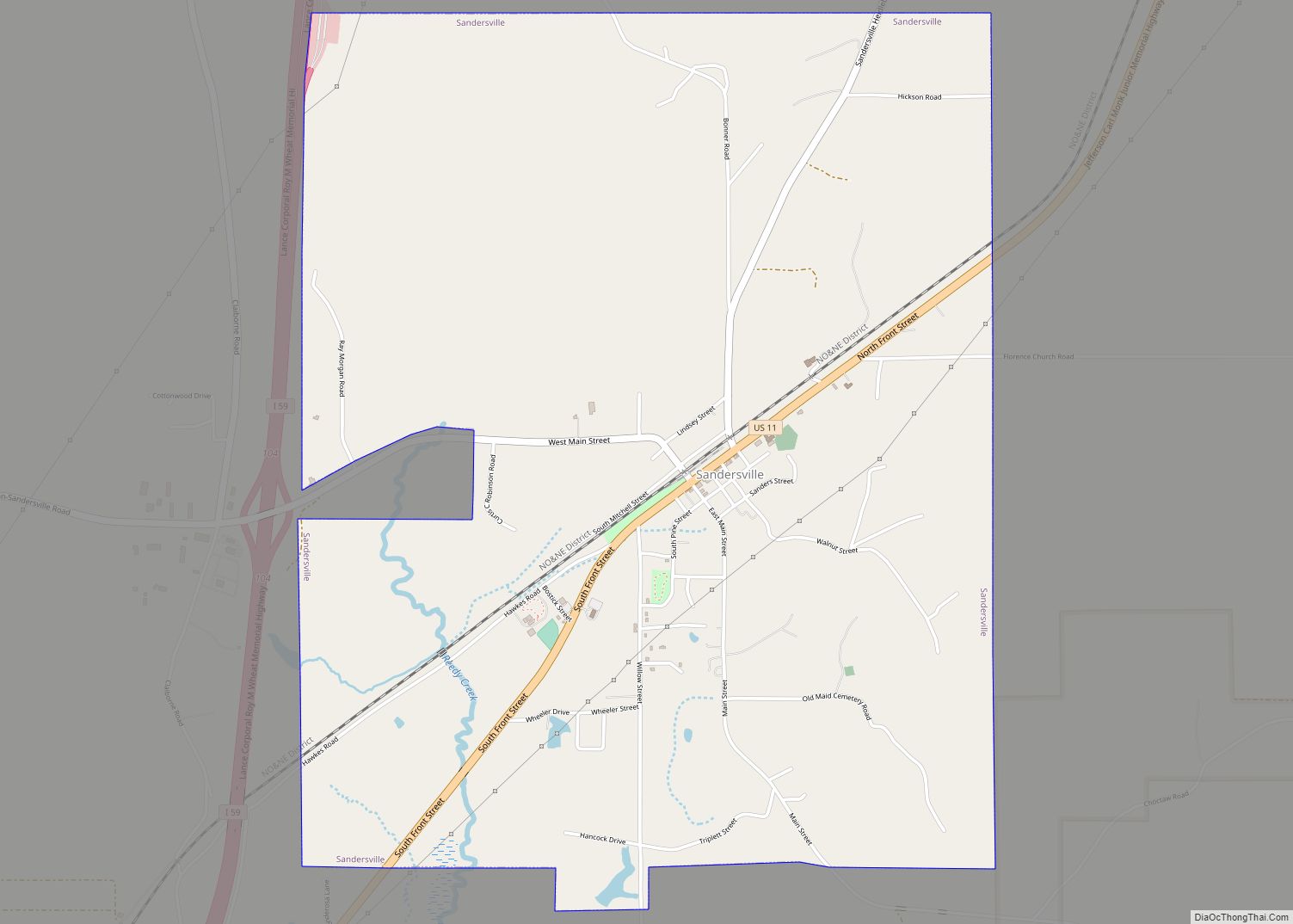

Jones County is in the southeastern portion of the U.S. state of Mississippi. As of the 2020 census, the population was 67,246. Its county seats are Laurel and Ellisville.

Jones County is part of the Laurel micropolitan area.

| Name: | Jones County |

|---|---|

| FIPS code: | 28-067 |

| State: | Mississippi |

| Founded: | 1826 |

| Named for: | John Paul Jones |

| Seat: | Laurel and Ellisville |

| Largest city: | Laurel |

| Total Area: | 700 sq mi (2,000 km²) |

| Land Area: | 695 sq mi (1,800 km²) |

| Total Population: | 67,246 |

| Population Density: | 96/sq mi (37/km²) |

| Time zone: | UTC−6 (Central) |

| Summer Time Zone (DST): | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Website: | jonescounty.com |

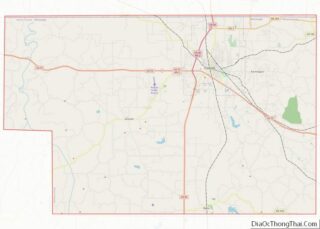

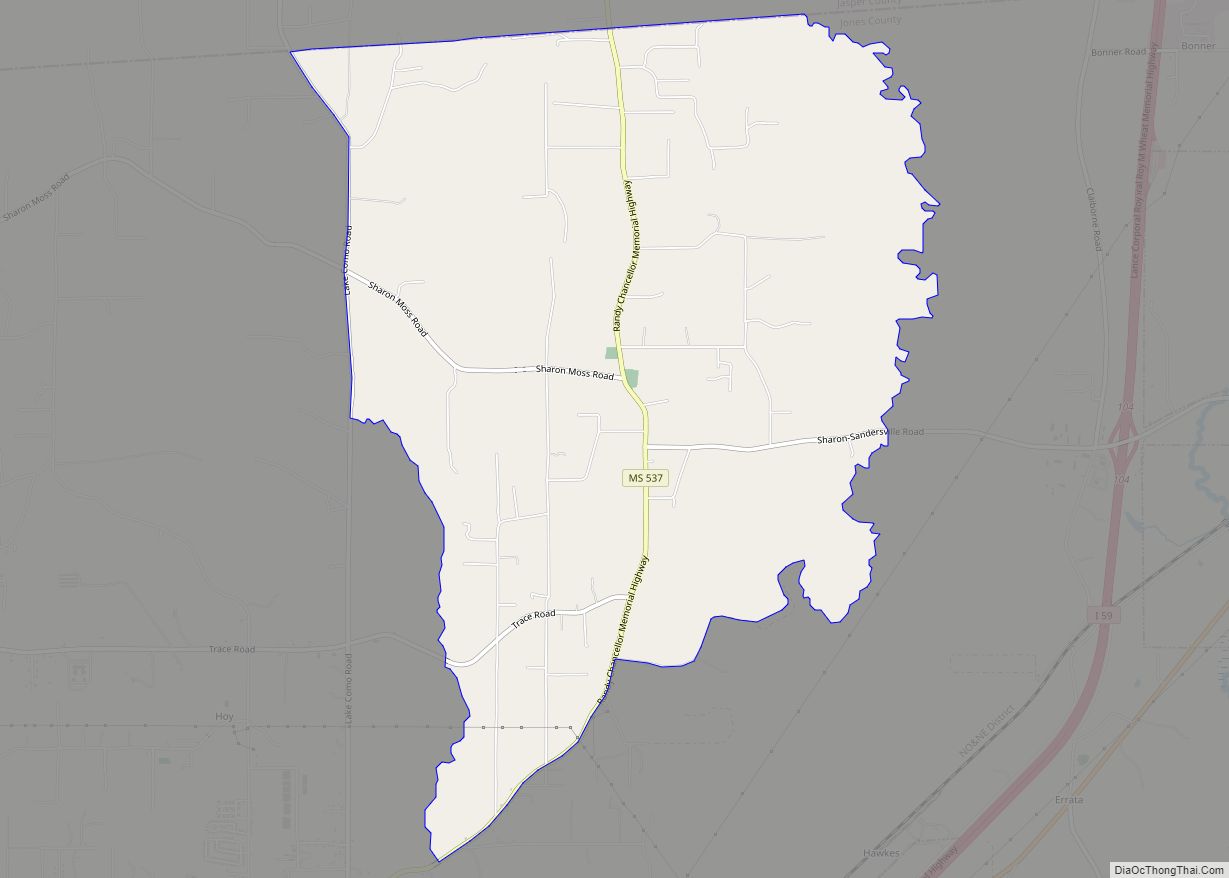

Jones County location map. Where is Jones County?

History

Less than a decade after Mississippi became the country’s 20th state, settlers organized this area of 700 sq mi (1,800 km) of pine forests and swamps for a new county in 1826. They named it Jones County after John Paul Jones, the early American Naval hero who rose from humble Scottish origin to military success during the American Revolution.

Ellisville, the county seat, was named for Powhatan Ellis, a member of the Mississippi Legislature who claimed to be a direct descendant of Pocahontas. During the economic hard times in the 1830s and 1840s, there was an exodus of population from Southeast Mississippi, both to western Mississippi and Louisiana in regions opened to white settlement after Indian Removal, and to Texas. The slogan “GTT” (“Gone to Texas”) became widely used.

Jones County was in an area of mostly yeomen farmers and lumbermen, as the pine forests, swamp and soil were not easily cultivated for cotton. In 1860, the majority of white residents were not slaveholders. Slaves made up only 12% of the total population in Jones County in 1860, the smallest percentage of any county in the state.

Civil War years

Soon after the election of Abraham Lincoln as United States president in November 1860, slave-owning planters led Mississippi to join South Carolina and secede from the Union. These were the two states with the largest holdings of slaves. On November 29, 1860, the Mississippi state legislature called for a “Convention of the people of Mississippi” to be held to “adopt such measures for vindicating the sovereignty of the State as shall appear to them to be demanded.” The Convention convened on January 7, 1861, and the elected representatives from the various counties of Mississippi voted 83–15 to secede from the Union. Notably, included in the vote to secede was the representative from Jones County, Mr. John H. Powell. Other Southern states would follow suit.

As Mississippi debated the secession question, the inhabitants of Jones County voted overwhelmingly for the anti-secessionist John Hathorne Powell, Jr. In comparison to the pro-secessionist J.M. Bayliss, who received 24 votes, Powell received 374. But, at the Secession Convention, Powell voted for secession. Legend has it that, for his vote, he was burned in effigy in Ellisville, the county seat.

The reality is more complicated. The only choices possible at the Secession Convention were voting for immediate secession on the one hand, or for a more cautious, co-operative approach to secession among several Southern states on the other. Powell almost certainly voted for the more conservative approach to secession—the only position available to him that was consistent with the anti-secessionist views of his constituency.

Mississippi’s Declaration of Secession reflected planters’ interests in its first sentence: “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery…” Jones County had mostly yeoman farmers and cattle herders, who were not slaveholders and had little use for a war over slavery.

During the American Civil War, Jones County and neighboring counties, especially Covington County to its west, became a haven for Confederate deserters. A number of factors prompted desertions. The lack of food and supplies was demoralizing, while reports of poor conditions back home made the men fear for their families’ survival. Small farms deteriorated from neglect as women and children struggled to keep them up. Their limited stores and livestock were often taken by the Confederate tax-in-kind agents, who took excessive amounts of yeoman farmers’ goods. Many residents and soldiers were also outraged over the Confederate government’s passing of the Twenty Negro Law, allowing wealthy plantation owners to avoid military service if they owned twenty slaves or more. In spite of the great displeasure the law caused, few men actually were affected by the law. For example, out of the roughly 38,000 Slaveowners living in the South in 1860, 200 in Virginia, 120 in North Carolina, 201 in Georgia, and 300 in South Carolina won exemptions.

On October 13, 1863, a band of deserters from Jones County and adjacent counties organized to protect the area from Confederate authorities and the crippling tax collections. The company, led by Newton Knight, formed a separate government, with Unionist leanings, known as the “Free State of Jones”, and fought a recorded 14 skirmishes with Confederate forces. They also raided Paulding, capturing five wagonloads of corn that had been collected for tax from area farms, which they distributed back among the local population. The company harassed Confederate officials. Deaths believed to be at their hands were reported in 1864 among numerous tax collectors, conscript officers, and other officials.

The governor was informed by the Jones County court clerk that deserters had made tax collections in the county impossible. By the spring of 1864, the Knight company had taken effective control from the Confederate government in the county. The followers of Knight raised an American flag over the courthouse in Ellisville, and sent a letter to Union General William T. Sherman declaring Jones County’s independence from the Confederacy. In July 1864, the Natchez Courier reported that Jones County had seceded from the Confederacy.

Scholars have disputed whether the county truly seceded, with some concluding it did not fully secede. While there have been numerous attempts to study Knight and his followers, the lack of documentation during and after the war has made him an elusive figure. The rebellion in Jones County has been variously characterized as consisting of local skirmishes to being a full-fledged war of independence. It assumed legendary status among some county residents and Civil War historians, culminating in the release of a 2016 feature film, Free State of Jones. The film is credited as “based on the books ‘The Free State of Jones’ by Victoria E. Bynum and ‘The State of Jones’ by Sally Jenkins and John Stauffer.”

The county changed its name to Davis County, after Confederate president Jefferson Davis, on November 30, 1865, and kept the name until four years later.

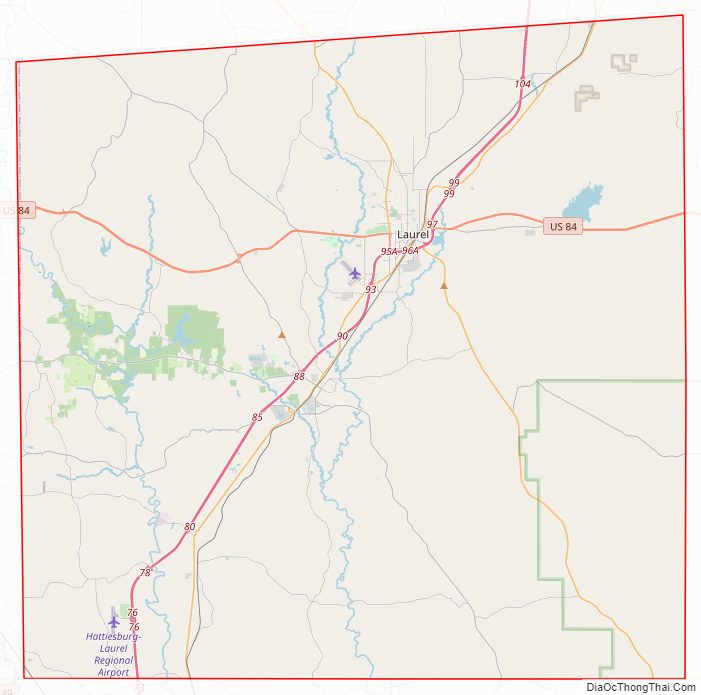

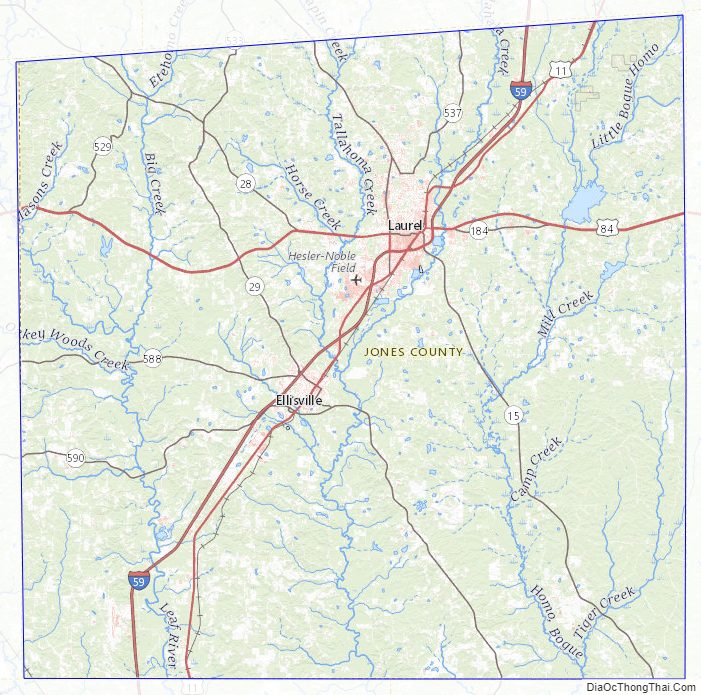

Jones County Road Map

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 700 square miles (1,800 km), of which 695 square miles (1,800 km) is land and 4.9 square miles (13 km) (0.7%) is water.

Adjacent counties

- Jasper County (north)

- Wayne County (east)

- Perry County (southeast)

- Forrest County (southwest)

- Covington County (west)

- Smith County (northwest)

National protected area

- De Soto National Forest (part)