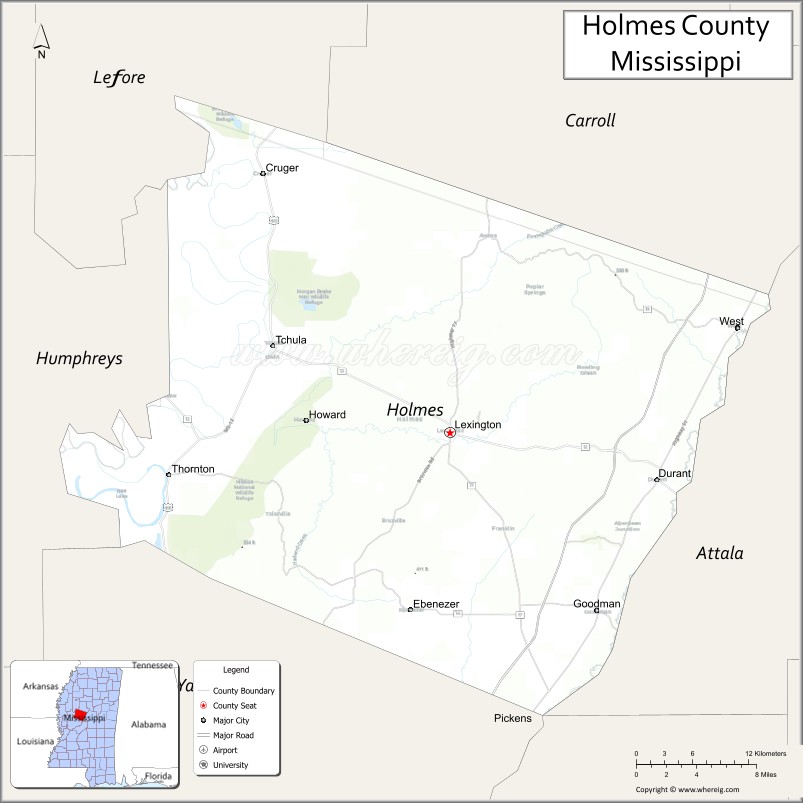

Holmes County is a county in the U.S. state of Mississippi; its western border is formed by the Yazoo River and the eastern border by the Big Black River. The western part of the county is within the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta. As of the 2020 census, the population was 17,000. Its county seat is Lexington. The county is named in honor of David Holmes, territorial governor and the first governor of the state of Mississippi and later United States Senator for Mississippi. Holmes County native, Edmond Favor Noel, was an attorney and state politician, elected as governor of Mississippi, serving from 1908 to 1912.

Cotton was long the commodity crop; before the Civil War, its cultivation was based on slave labor and the majority of the population consisted of enslaved African Americans. Planters generally developed their properties along the riverfronts. After the war, many freedmen acquired land in the bottomlands of the Delta by clearing and selling timber to raise the purchase price, but most lost their land during difficult financial times at the end of the century, becoming tenant farmers or sharecroppers. With an economy based on agriculture, the county had steep population declines from 1940 to 1970, due to mechanization of farm labor, and the second wave of the Great Migration. African Americans migrated from the Deep South especially to West Coast cities, where jobs were plentiful in the buildup of the defense industry.

Some African Americans had reacquired land in Holmes County in the 1940s under New Deal programs. By 1960, Holmes County’s 800 independent black farmers owned 50% of the land, a higher number of such farmers than elsewhere in the state. They were integral members of the Civil Rights Movement during the 1960s. In 1967, eight of ten black candidates to run for local county office were landowning farmers; they were the first African Americans to run for office in the county since Reconstruction. Holmes had more candidates running for offices for the Freedom Democratic Party than did any other county.

Robert G. Clark, Jr., a teacher in Holmes County, was elected as state representative in 1967, the first black person to be elected to state government in the 20th century. He served as the only African American in the state house until 1976. He continued to be re-elected to the state legislature from Holmes County until 2003. In the late 20th century, he was elected to the first of three terms as Speaker of the state House.

| Name: | Holmes County |

|---|---|

| FIPS code: | 28-051 |

| State: | Mississippi |

| Founded: | 1833 |

| Named for: | David Holmes |

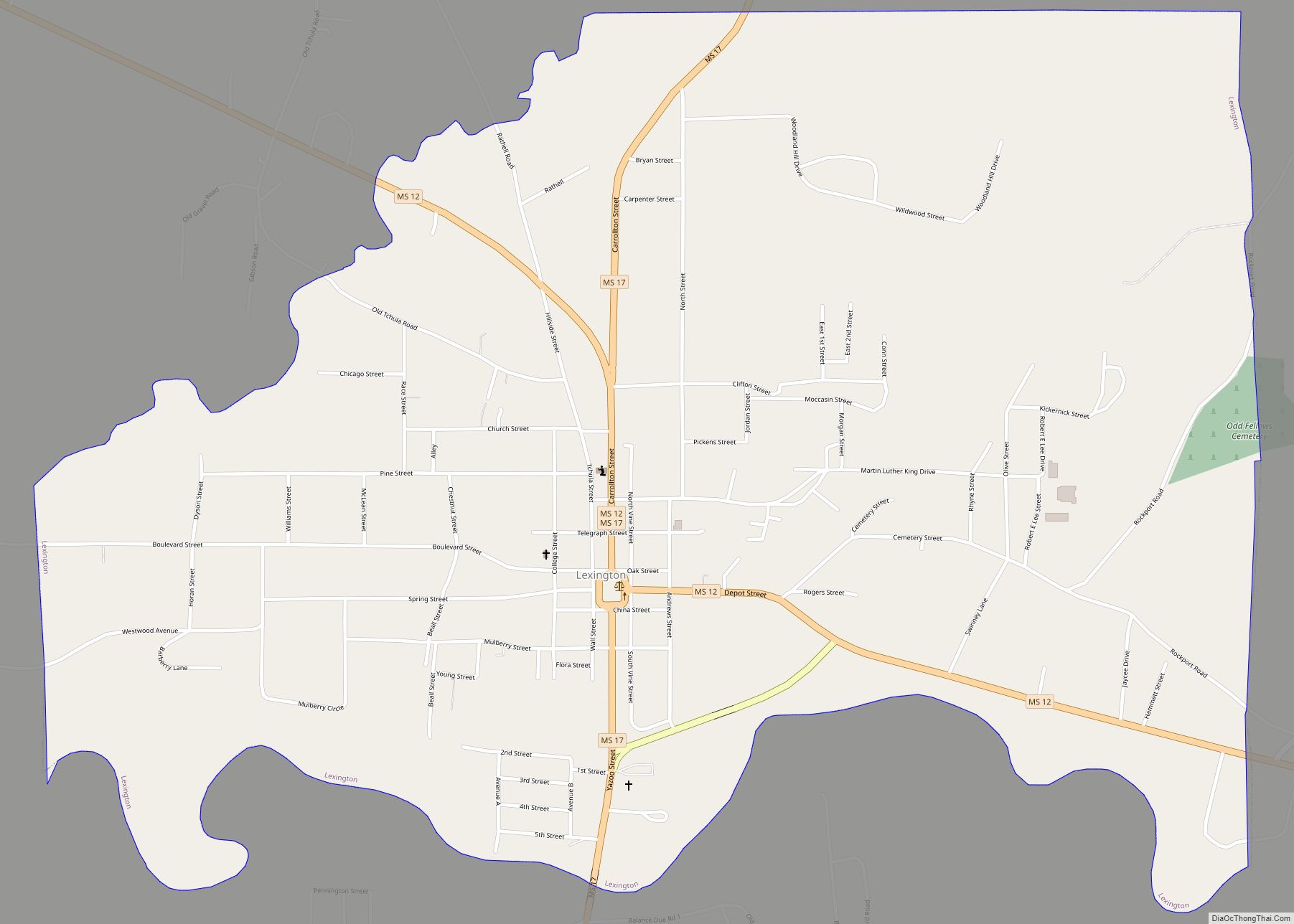

| Seat: | Lexington |

| Largest city: | Durant |

| Total Area: | 765 sq mi (1,980 km²) |

| Land Area: | 757 sq mi (1,960 km²) |

| Total Population: | 17,000 |

| Population Density: | 22/sq mi (8.6/km²) |

| Time zone: | UTC−6 (Central) |

| Summer Time Zone (DST): | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Website: | holmescountyms.org |

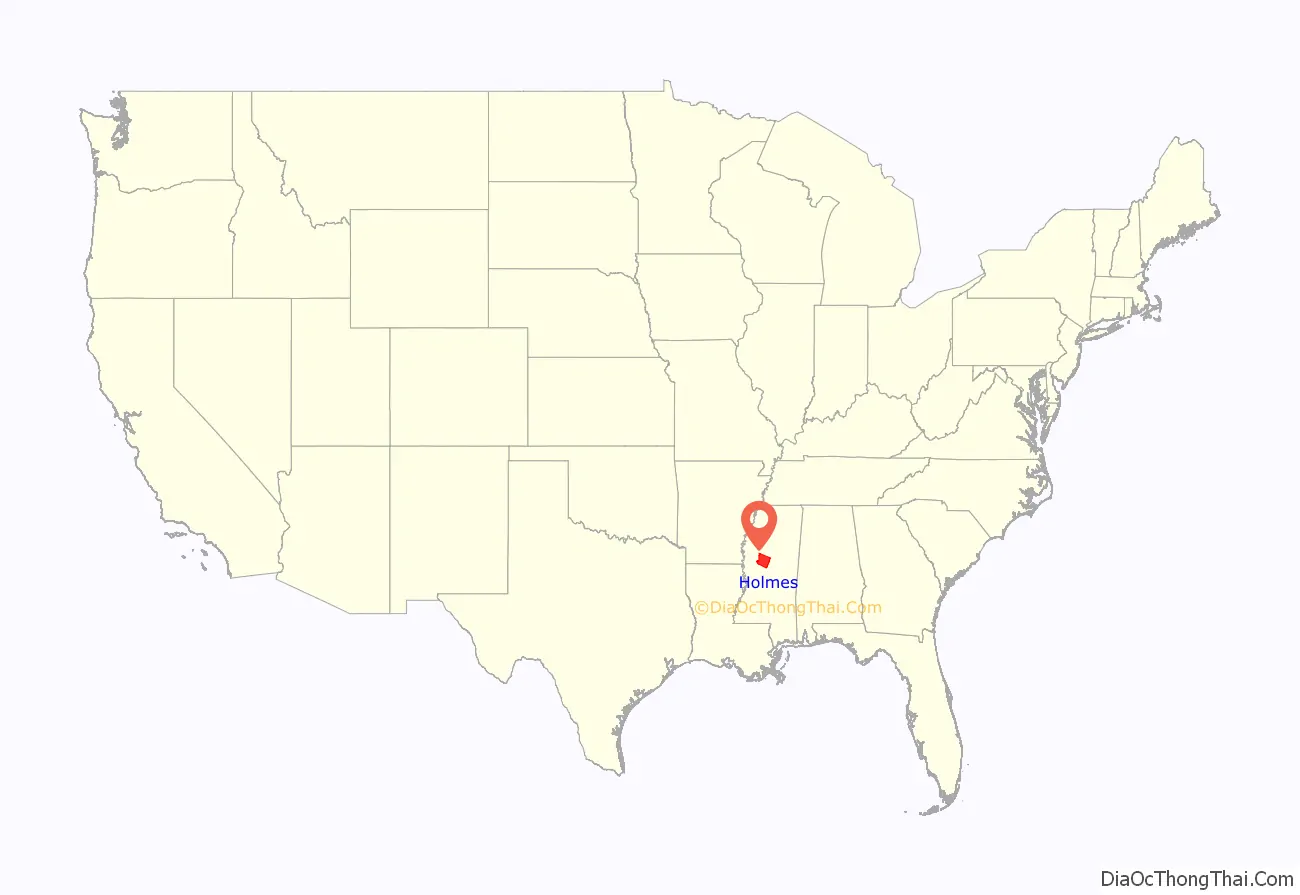

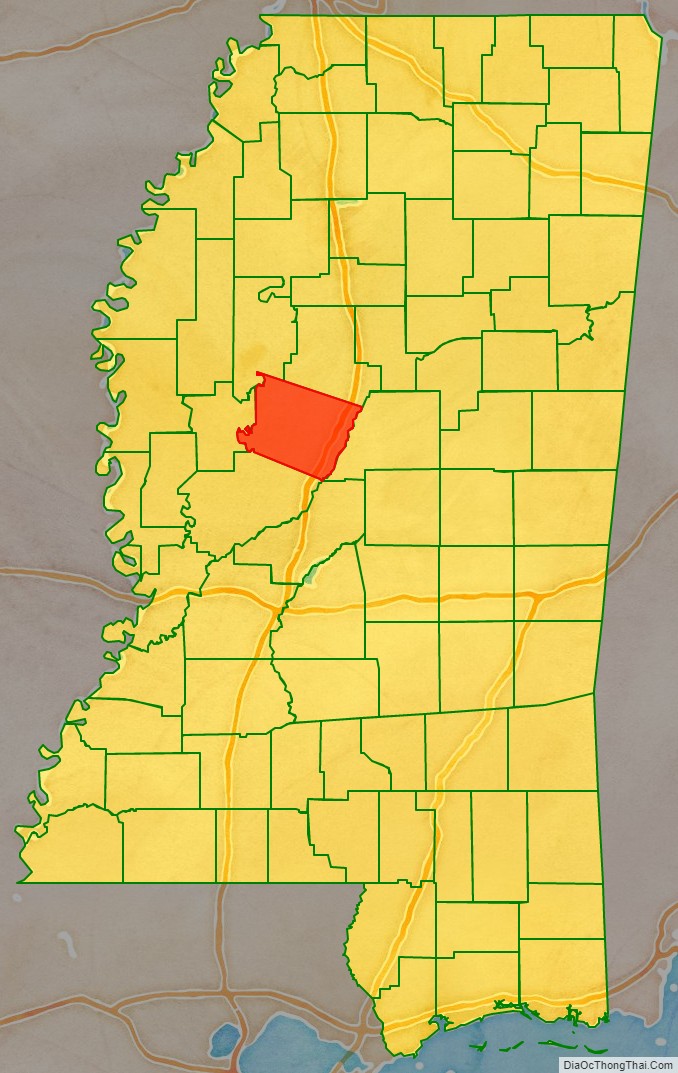

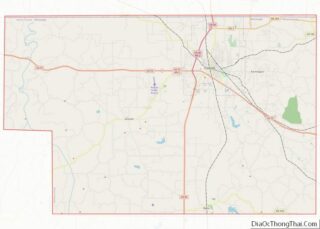

Holmes County location map. Where is Holmes County?

History

The western border of the county is formed by the Yazoo River; it is next to the Mississippi Delta, and shares its characteristics. The eastern border is formed by the Big Black River and the eastern part has hills. The county was developed for cotton plantations in the antebellum era before the American Civil War, with most properties of the period located along the riverfronts for transportation access. Due to the plantation economy and reliance on slave labor, the county was majority black before the Civil War. It has continued to be majority black (see Demographics). Because of these characteristics, it is included among the 200 counties defined as part of the Black Belt region that curves across the South, into Texas.

“According to U.S. Census data, the 1860 Holmes County population included 5,806 whites, 10 “free colored” and 11,975 slaves. By the 1870 census, the white population had increased about 6% to 6,145, and the “colored” population had increased about 10% to 13,225.” After the war, many freedmen and white migrants went to Holmes County and other parts of the Mississippi Delta, where they developed the bottomlands behind the riverfront properties, clearing and selling timber in order to buy their own lands. Workers were also attracted to the Delta area by higher than usual wages on the plantations, which had a labor shortage in the transition to a free labor economy.

By the turn of the 20th century, a majority of the landowners in the Delta counties were black. Effectively African-Americans were disenfranchised by the new constitution of 1890; the loss of political power added to their economic problems associated with the financial Panic of 1893. Unable to gain credit, many of the first generations of African-American landowners lost their properties by 1920. In this period, they were also competing for land with the better-funded timber and railroad companies. Afterward, African-Americans were forced to become sharecroppers or tenant farmers to make a living.

The period after Reconstruction and through the early 20th century had the highest incidence of white people lynching black people. Holmes County had 10 documented lynchings in the period from 1877 to 1950, most around the turn of the 20th century. Two lynchings took place in the county seat of Lexington, Mississippi in the 1940s.

White planters continued to recruit labor in the area, as freedmen wanted to work on their own account. The first Chinese immigrant laborers entered the Delta in the late 1870s. From 1900-1930, additional Chinese immigrants arrived in Mississippi, including some to Holmes County. They worked hard to leave field labor and often became merchants, especially becoming grocers of small stores in the rural Delta towns. As their socioeconomic status changed, the Chinese Americans carved out a niche “between black and white”, gaining admission to white schools for their children through court challenges. With the decline of small towns, most Chinese Americans moved to larger cities through the 20th century. In Mississippi, the number of ethnic Chinese has increased overall in the state through 2010, although it is still small in total – fewer than 5,000.

During the New Deal, the Roosevelt administration worked through the Farmers Home Administration to provide low-interest loans in order to increase black land ownership. They also established a co-op cotton gin to be used by farmers in the project. In Holmes County, numerous African-Americans became landowners in the 1930s and 1940s through this program. They were fiercely independent and later were among strong supporters of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, even as white people kept a grip on economic and political power through banks, police and the county courthouse. Although there had been outmigration, the population of the county in 1960 was still 42% black.

The USDA Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service (ASCS) (established under another name in the 1930s) carried out its programs on a county-wide level. County boards were elected annually by farmers to work on local programs, and to make approval of loans to farmers and similar issues. Although African-Americans made up a large portion of landowners in Holmes County, they were disenfranchised from voting and excluded from participating on the board. They were generally deprived of potential benefits through this program, as part of the pattern of racial discrimination against them across the South.

Beginning in the World War II period, the population of Holmes County declined markedly from its peak of 1940; through 1970 thousands left, with most African-Americans going to the West Coast or in Midwestern cities in the second wave of the Great Migration, taking jobs in the booming defense industry. From 1950 to 1960, for instance, some 6,000 black people left the county, a decline of nearly 19%. But in 1960 the county was still 72% black, with a total population of 27,100.

Even with these problems, in 1960 Holmes County had more independent black farmers than did any other county in the state: 800 black farmers owned 50% of the land in the county. They were among those who initiated the civil rights movement, particularly farmers of Mileston, where the soil was rich. They invited organizers of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to come to Mileston to help them take action. The majority of the first fourteen black people who attempted to register to vote on April 9, 1963 were landowners. Holmes County became the site of renewed organizing of grassroots efforts for African-American civil rights, with people designated as responsible for its Beats and precincts.

In 1954, the White Citizens Council was established to expressly to oppose desegregation of public schools after the United States Supreme Court ruling that year in Brown v. Board of Education, finding segregation to be unconstitutional. They raised funds to support whites-only schools, and conducted economic boycotts of blacks suspected of civil rights activism, as well as social and political pressure against whites who crossed them. Among their targets in the latter category was Hazel Brannon Smith, publisher and editor of two local papers in Lexington. For three years, her customers resisted the council’s effort to boycott her and cut out her advertising; the Council started a rival newspaper to try to take away her business. Opponents arranged for her husband to be fired from his job as county hospital administrator, and a group firebombed two of her papers. She received a Pulitzer Prize for journalism in 1964 for her editorials about the civil rights movement during this period.

The Freedom Democratic Party was organized in 1964 to work on black voter registration and education, and continued after passage of civil rights laws, in order to implement such laws. For instance, where white Democratic Party officials had defined the very large Lexington precinct, which held the majority of population, the county chapter of the FDP organized its own sub-precincts within it in order to communicate better with the community. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were important but had to be implemented on the local level, where resistance to black voting continued to be strong, sometimes becoming violent.

The FDP worked with residents to register African-American voters and encourage them to vote. As resistance continued by white officials, in November 1965 a federal registrar was assigned to Holmes County, based on residents’ petitions about the circuit clerk’s discrimination over a 4-month period. After this, 2,000 black voters were registered in two months.

The FDP also worked with local people to run for positions on the ASCS board. In the fall of 1965, six black farmers were elected to the county board, with four as alternates. This gave them a voice in determining how local programs would run. But discrimination in USDA programs continued and was widespread, as shown by a late 20th-century national class-action suit, Pigford v. Glickman, which was settled in 1999. Payments to members of the class affected continued into the 21st century.

In 1966 many communities in the county concentrated on setting up the new federal Head Start program for young children. The FDP continued to work with other communities on correcting unfair hiring at factories and unequal administration of welfare, as well as trying to end discrimination at eating places. From 1966 on, the FDP registered an increasing number of black voters and gained their participation in elections. By November 1967, nearly 6,000 new voters were registered in the county.

In 1967 black farmers and landowners, who had been part of the Movement since the early 1960s, accounted for eight of the ten candidates who ran for local and state offices: Thomas C. “Top Cat” Johnson, Ed Noel McGaw, Jr.; Ward Montgomery; John Malone; Willie James Burns; John Daniel Wesley; Griffin McLaurin, and Ralthus Hayes. McLaurin was elected as constable of one of the beats in the county.

Robert G. Clark (born 1928) and Robert Smith, both teachers, had joined the Movement in 1966 and ran for state representative and county sheriff, respectively. Clark was a member of a landowning family in Ebenezer; he had a master’s degree and had nearly finished his PhD from Michigan State University. He won a seat as the first and only black elected in 1967 to the Mississippi House of Representatives. By 2000, Clark had been re-elected to eight four-year terms in the state house and had been elected as Speaker three times since 1992. It was not until 1976 that another African American was elected to the state legislature, but then the number increased. Several blacks were elected to local offices in Holmes County well before that.

White people have also left the county since the mid-20th century because of declining work opportunities. Agribusinesses have bought up large tracts of land, and the number of independent farmers has declined markedly. By 2010, the total population was less than half that of 1940. Still largely rural, Holmes County in the 21st century has problems associated with poverty and limited access to health care; it has the lowest life expectancy of any county in the United States, for both men and women.

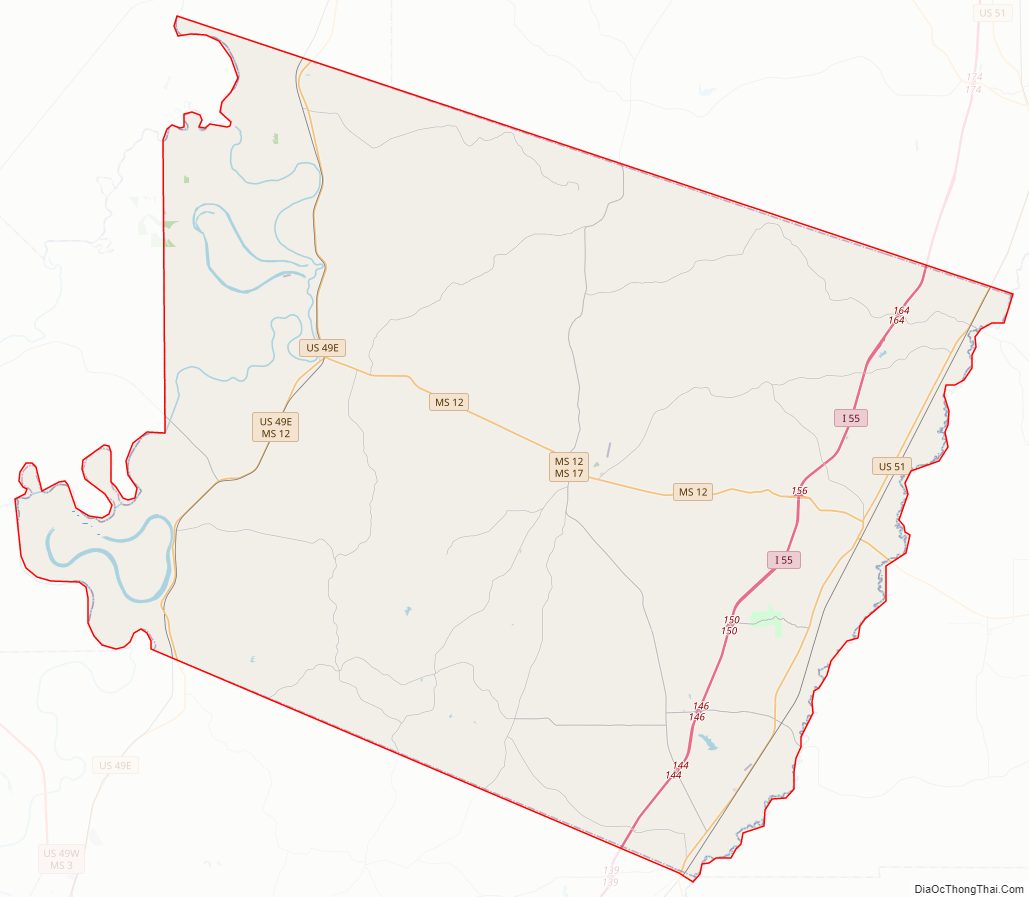

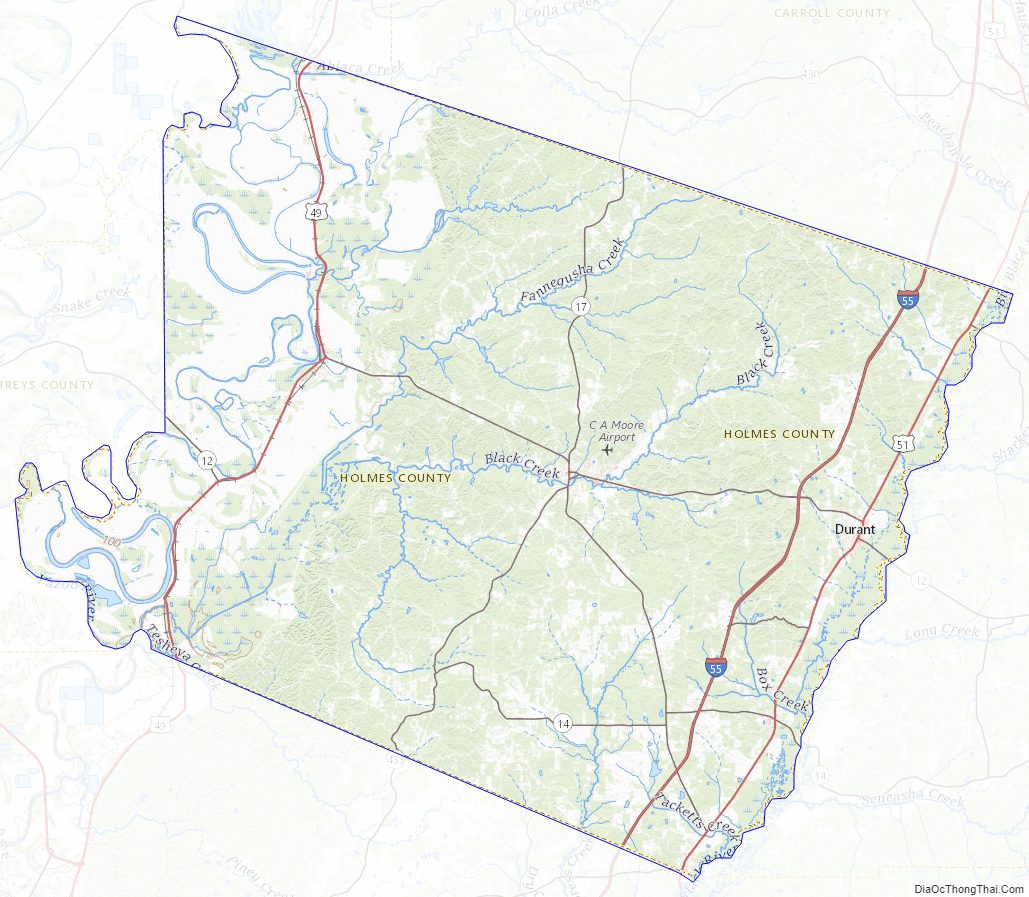

Holmes County Road Map

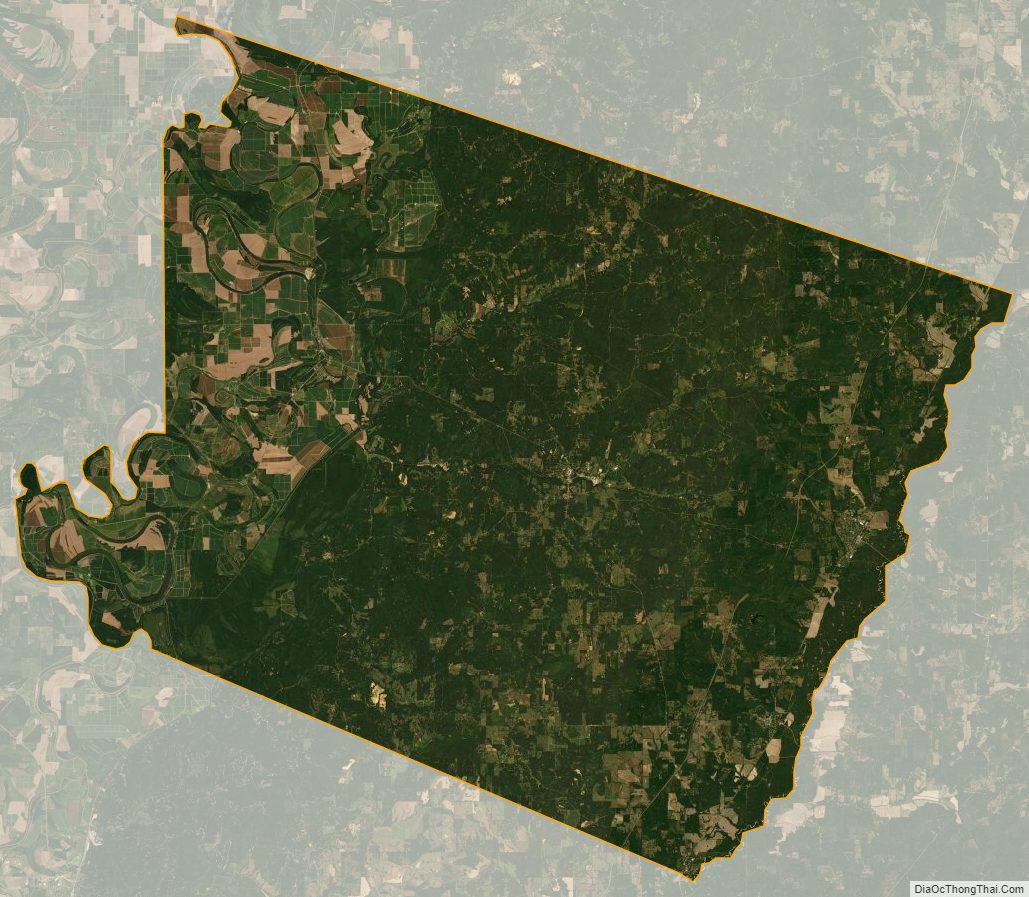

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 765 square miles (1,980 km), of which 757 square miles (1,960 km) is land and 7.9 square miles (20 km) (1.0%) is water.

Major highways

- Interstate 55

- U.S. Route 49

- U.S. Route 51

- Mississippi Highway 12

- Mississippi Highway 14

- Mississippi Highway 17

- Mississippi Highway 19

Adjacent counties

- Carroll County (north)

- Attala County (east)

- Yazoo County (south)

- Humphreys County (west)

- Leflore County (northwest)

National protected areas

- Hillside National Wildlife Refuge (part)

- Mathews Brake National Wildlife Refuge (part)

- Morgan Brake National Wildlife Refuge

- Theodore Roosevelt National Wildlife Refuge (part)