| Name: | St. Clair County |

|---|---|

| FIPS code: | 17-163 |

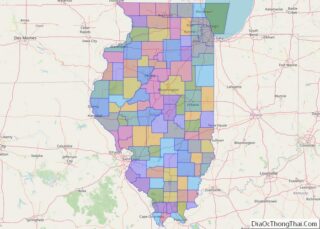

| State: | Illinois |

| Founded: | 1790 |

| Named for: | Arthur St. Clair |

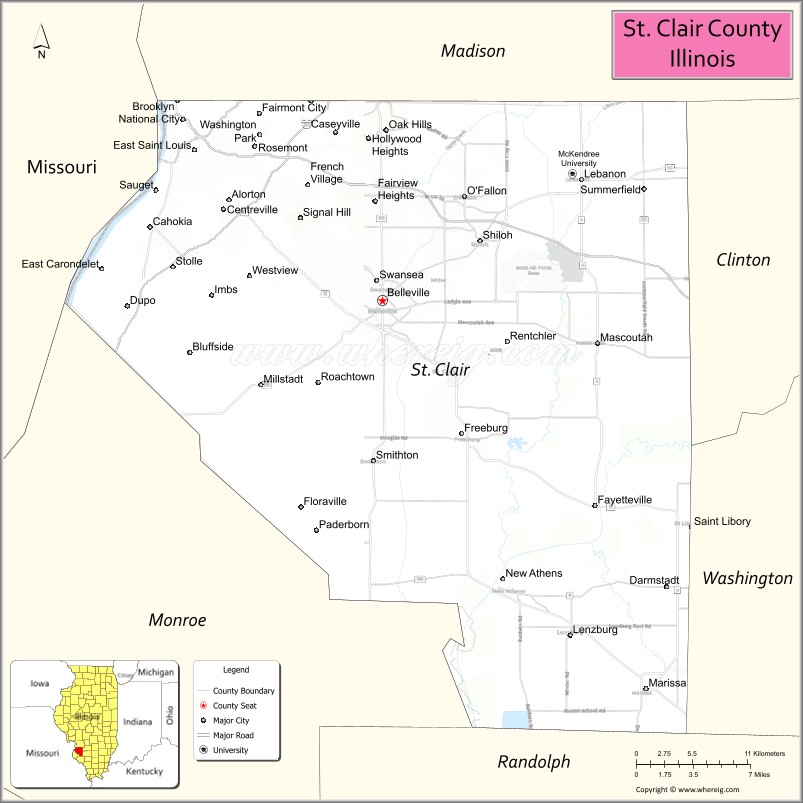

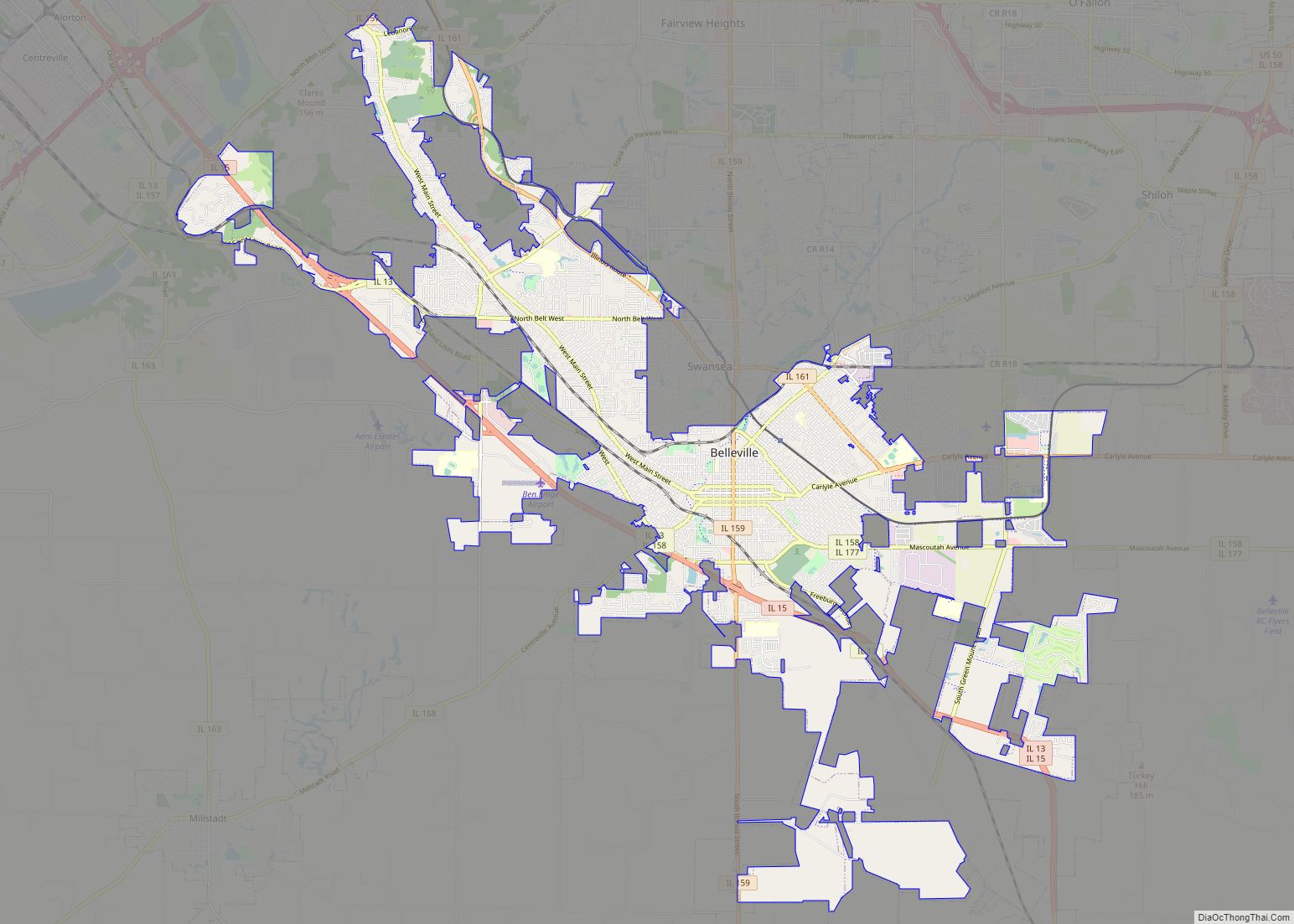

| Seat: | Belleville |

| Largest city: | Belleville |

| Total Area: | 674 sq mi (1,750 km²) |

| Land Area: | 658 sq mi (1,700 km²) |

| Total Population: | 257,400 |

| Population Density: | 380/sq mi (150/km²) |

| Time zone: | UTC−6 (Central) |

| Summer Time Zone (DST): | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Website: | www.co.st-clair.il.us |

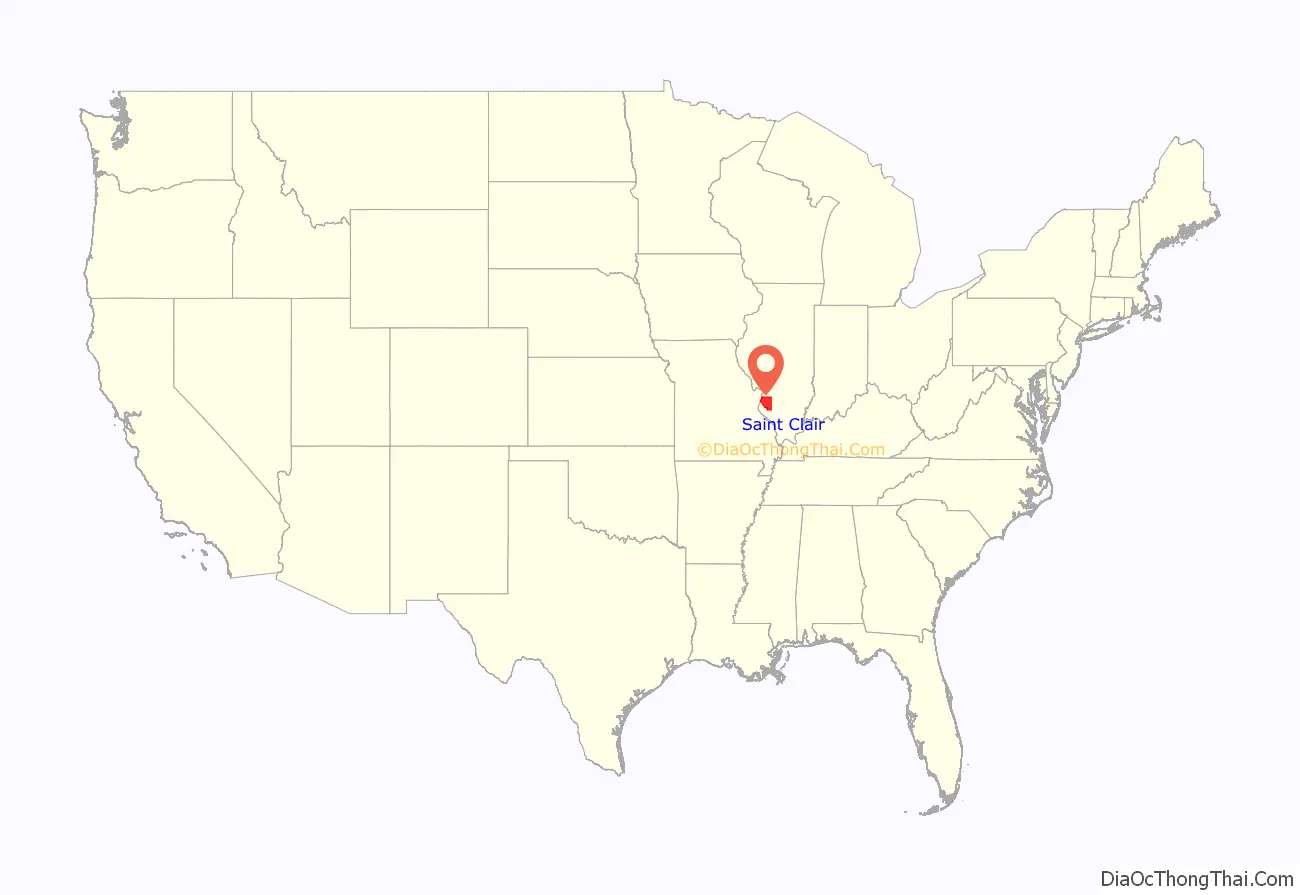

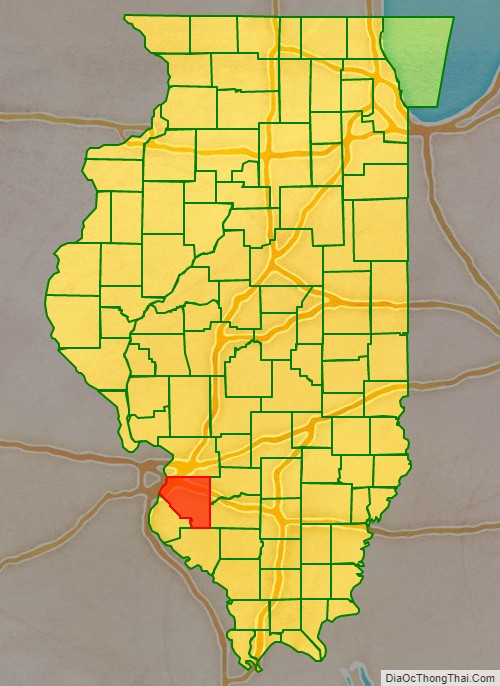

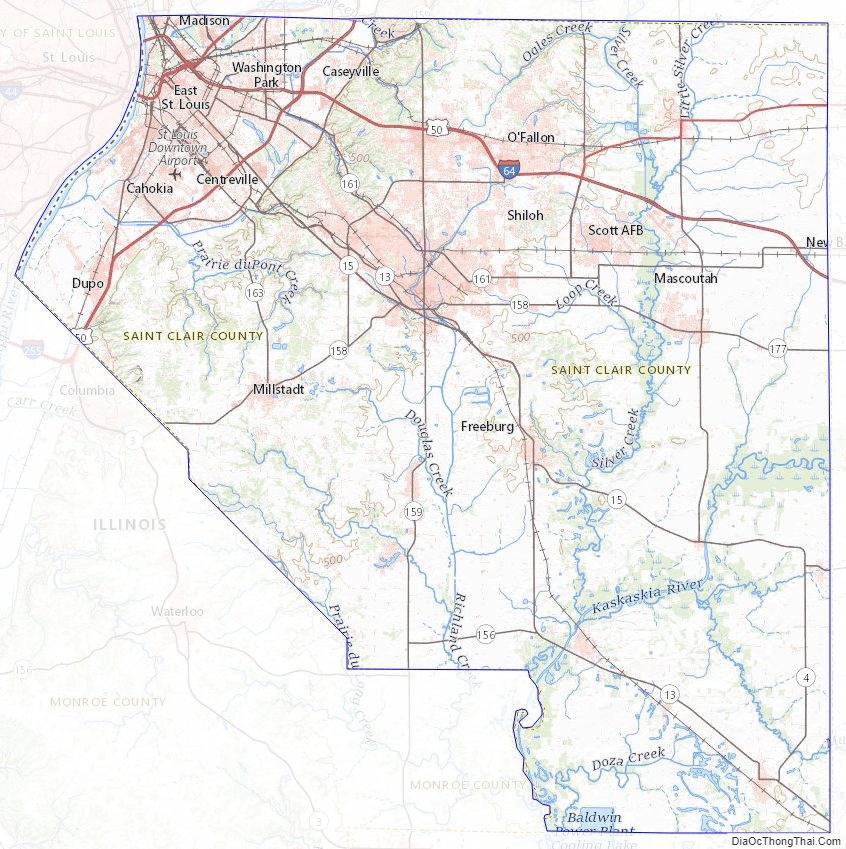

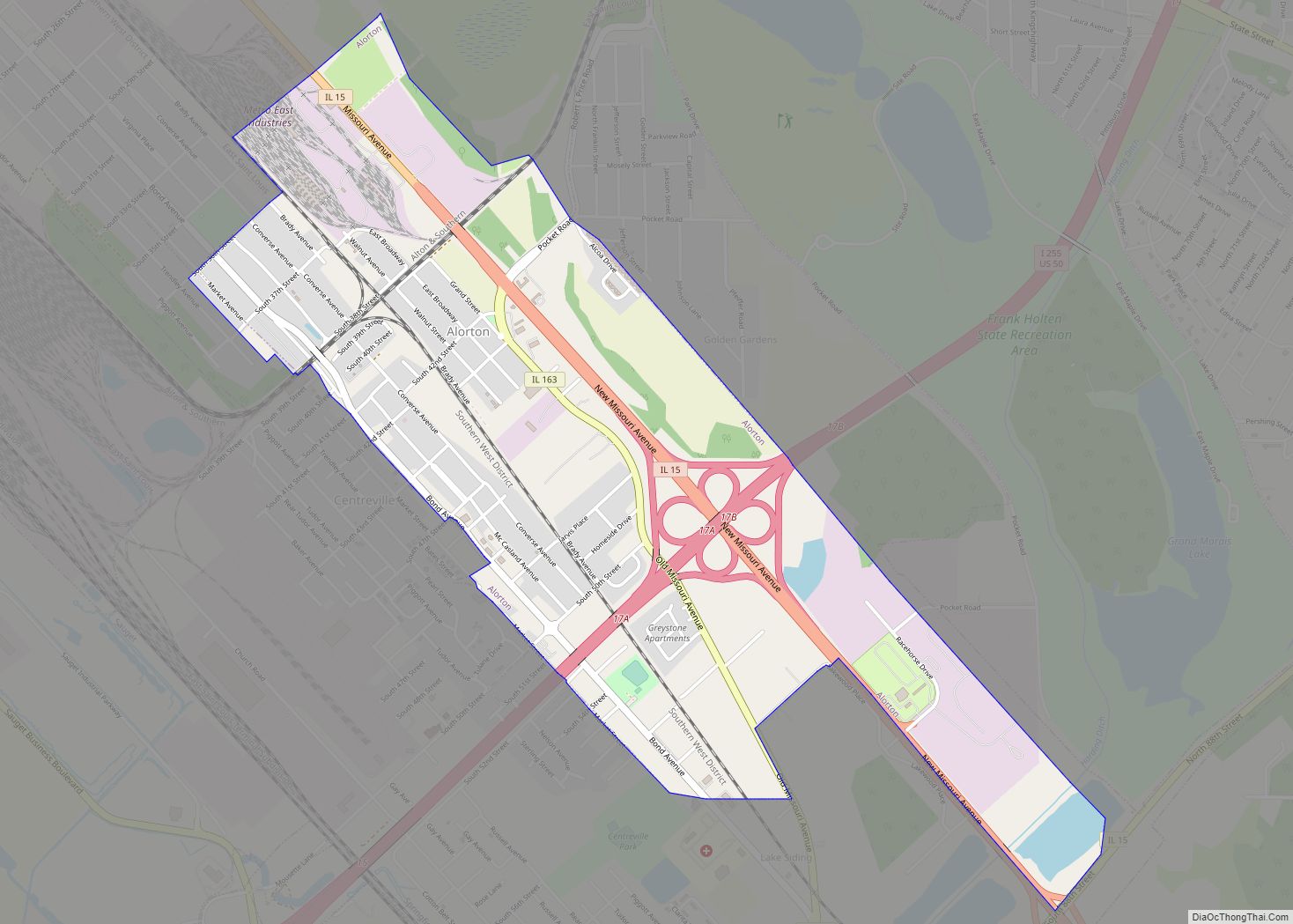

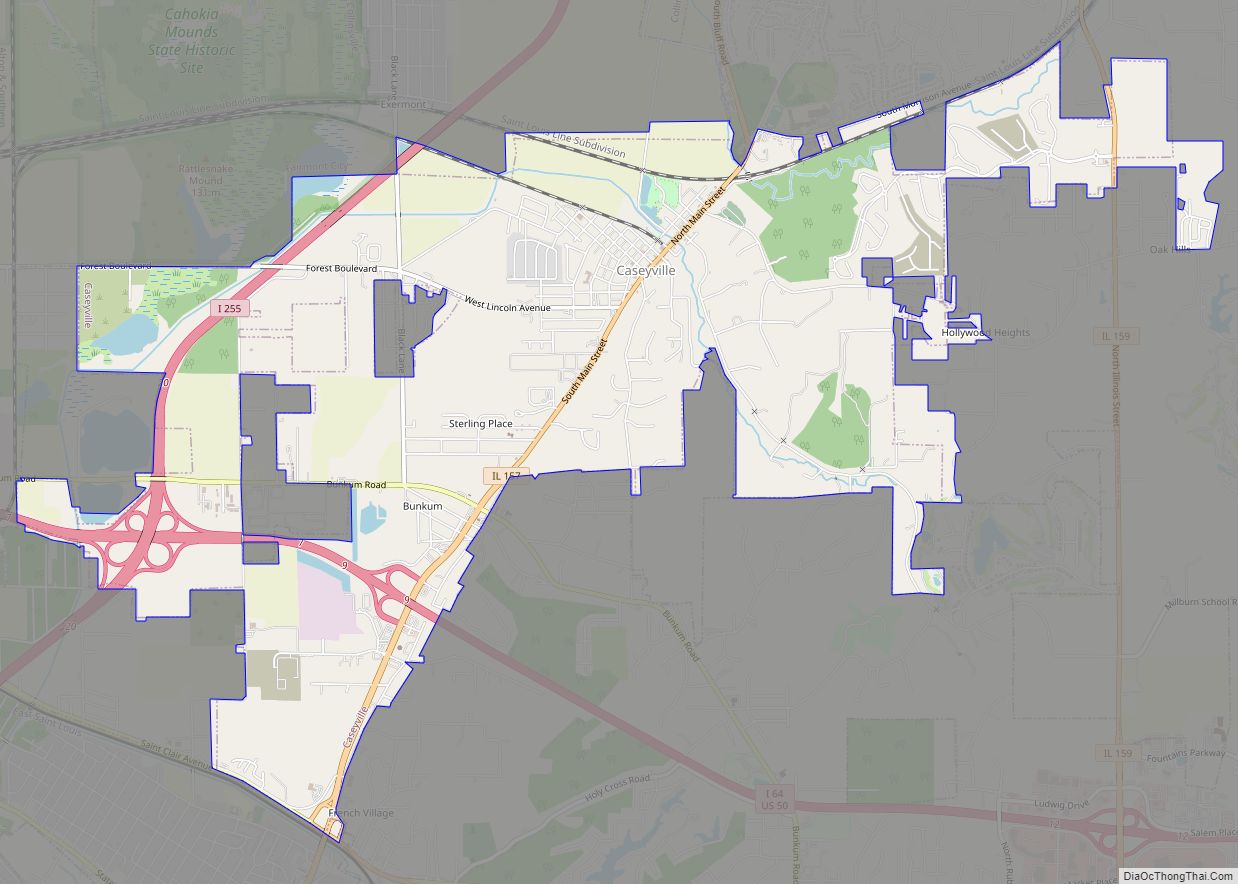

St. Clair County location map. Where is St. Clair County?

History

This area was occupied for thousands of years by cultures of indigenous peoples. The first modern explorers and colonists of the area were French and French Canadians, founding a mission settlement in 1697 now known as Cahokia Village. After Great Britain defeated France in the Seven Years’ War in 1763 and absorbed its territory in North America east of the Mississippi River, British-American colonists began to move into the area. Many French Catholics moved to settlements west of the river rather than live under British Protestant rule.

After the United States achieved independence in the late 18th century, St. Clair County was the first county established in present-day Illinois; it antedates Illinois’ existence as a separate jurisdiction. The county was established in 1790 by a proclamation of Arthur St. Clair, first governor of the Northwest Territory, who named it after himself.

The original boundary of St. Clair county covered a large area between the Mackinaw and Ohio rivers. In 1801, Governor William Henry Harrison re-established St. Clair County as part of the Indiana Territory, extending its northern border to Lake Superior and the international border with Rupert’s Land.

When the Illinois Territory was created in 1809, Territorial Secretary Nathaniel Pope, in his capacity as acting governor, issued a proclamation establishing St. Clair and Randolph County as the two original counties of Illinois.

St. Clair County as it was re-established in 1809. This diagonal border line had been drawn by the Indiana Territorial government in 1803.

St. Clair County between 1812 and 1813

St. Clair County between 1813 and 1816

St. Clair County between 1816 and 1818

St. Clair County between 1818 and 1825

St. Clair County between 1825 and 1827

St. Clair County from 1827 to present

Originally developed for agriculture, this area became industrialized and urbanized in the area of East St. Louis, Illinois, a city that developed on the east side of the Mississippi River from St. Louis, Missouri. It was always strongly influenced by actions of businessmen from St. Louis, who were initially French Creole fur traders with western trading networks.

In the 19th century, industrialists from St. Louis put coal plants and other heavy industry on the east side of the river, developing East St. Louis. Coal from southern mines was transported on the river to East St. Louis, then fed by barge to St. Louis furnaces as needed. After bridges spanned the river, industry expanded.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the cities attracted immigrants from southern and eastern Europe and from the South. In 1910 there were 6,000 African Americans in the city. With the Great Migration underway from the rural South, to leave behind Jim Crow and disenfranchisement, by 1917, the African-American population in East St. Louis had doubled. Whites were generally hired first and given higher–paying jobs, but there were still opportunities for American blacks. If hired as strikebreakers, they were resented by white workers, and both groups competed for jobs and limited housing in East St. Louis. The city had not been able to keep up with the rapid growth of population. The United States was developing war industries to support its eventual entry into the Great War, now known as World War I.

In February 1917 tensions in the city arose as white workers struck at the Aluminum Ore Company. Employers fiercely resisted union organizing, sometimes with violence. In this case they hired hundreds of blacks as strikebreakers. White workers complained to the city council about this practice in late May. Rumors circulated about an armed African American man robbing a white man, and whites began to attack blacks on the street. The governor ordered in the National Guard and peace seemed restored by early June.

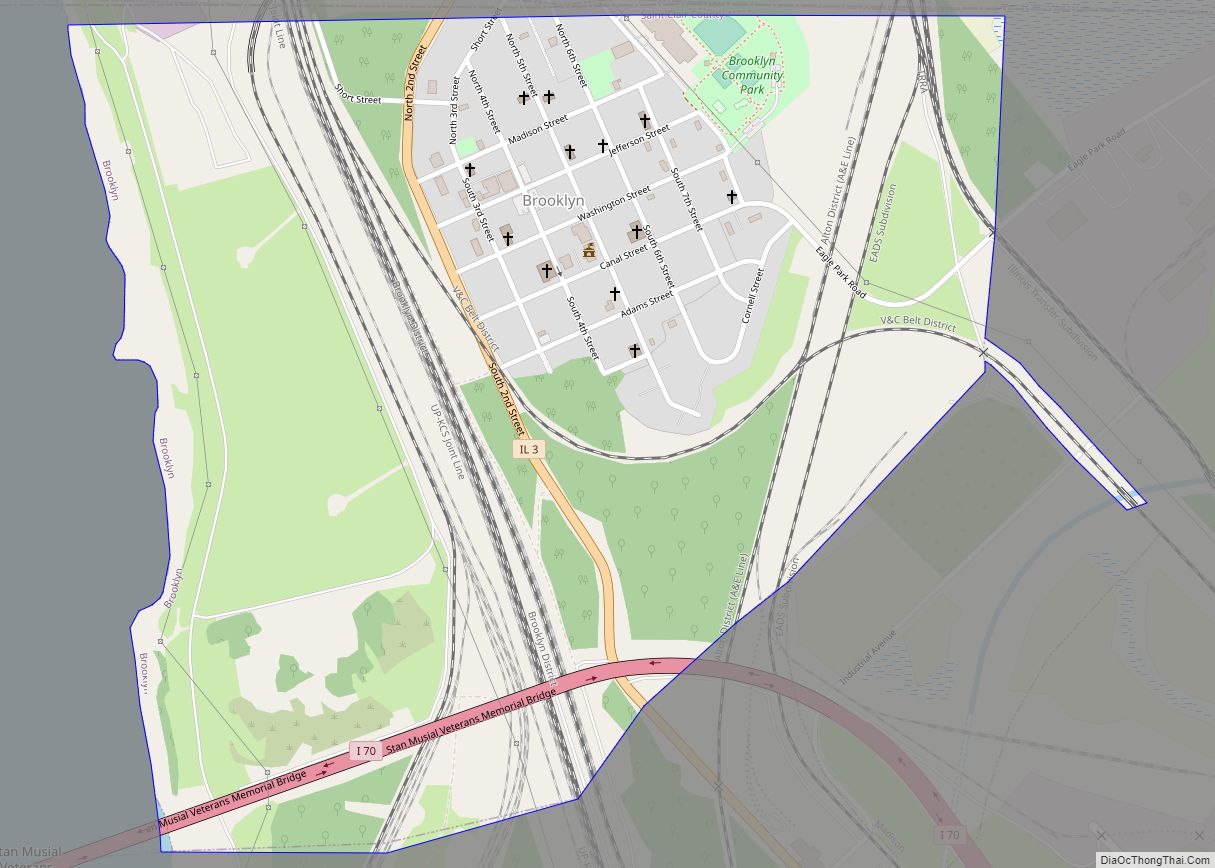

“On July 1, a white man in a Ford shot into black homes. Armed African-Americans gathered in the area and shot into another oncoming Ford, killing two men who turned out to be police officers investigating the shooting.” Word spread and whites gathered at the Labor Temple; the next day they fanned out across the city, armed with guns, clubs, anything they could use against the blacks they encountered. From July 1 through July 3, 1917, the East St. Louis riots engulfed the city, with whites attacking blacks throughout the city, pulling them from streetcars, shooting and hanging them, burning their houses. During this period, some African Americans tried to swim or use boats to get to safety; thousands crossed the Eads Bridge to St. Louis, seeking refuge, until the police closed it off. The official death toll was 39 blacks and nine whites, but some historians believe more blacks were killed. Because the riots were racial terrorism, the Equal Justice Initiative has included these deaths among the lynchings of African Americans in the state of Illinois in its 2017 3rd edition of its report, Lynching in America.

The riots had disrupted East St. Louis, which had seemed to be on the rise as a flourishing industrial city. In addition to the human toll, they cost approximately $400,000 in property damage (over $8 million, in 2017 US Dollars ). They have been described as among the worst labor and race-related riots in United States history, and they devastated the African-American community.

Rebuilding was difficult as workers were being drafted to fight in World War I. When the veterans returned, they struggled to find jobs and re-enter the economy, which had to shift down to peacetime.

In the late 20th century, national restructuring of heavy industry cost many jobs, hollowing out the city, which had a marked decline in population. Residents who did not leave have suffered high rates of poverty and crime. In the early 21st century, East St. Louis is a site of urban decay. Swathes of deteriorated housing were demolished and parts of the city have become urban prairie. In 2017 the city marked the centennial of the riots that had so affected its residents.

Other cities in St. Clair County border agricultural or vacant lands. Unlike the suburbs on the Missouri side of the metro area, those in Metro-East are typically separated by agriculture, or otherwise undeveloped land left after the decline of industry. The central portion of St. Clair county is located on a bluff along the Mississippi River. This area is being developed with suburban housing, particularly in Belleville, and its satellite cities. The eastern and southern portion of the county is sparsely populated. The older small communities and small tracts of newer suburban villages are located between large areas of land devoted to corn and soybean fields, the major commodity crops of the area.

According to the St. Clair County Historical Society, the county flag was designed in 1979 by Kent Zimmerman, a senior at O’Fallon Township High School. Zimmerman’s flag won first place in a contest against submissions by more than 40 grade school and high school students from throughout the county. The winning entry features the outline of St. Clair County with an orange moon, a stalk of corn, and a pickaxe against a background of three stripes alternating green, yellow, and green.

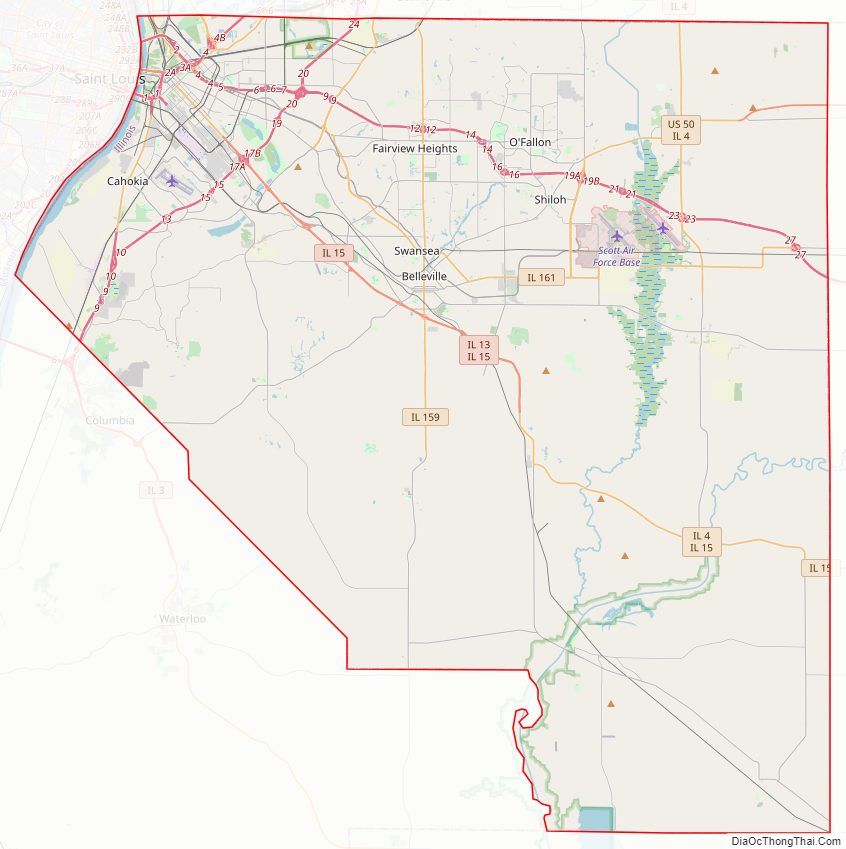

St. Clair County Road Map

Geography

According to the US Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 674 square miles (1,750 km), of which 658 square miles (1,700 km) is land and 16 square miles (41 km) (2.4%) is water.

Climate and weather

In recent years, average temperatures in the county seat of Belleville have ranged from a low of 22 °F (−6 °C) in January to a high of 90 °F (32 °C) in July, although a record low of −27 °F (−33 °C) was recorded in January 1977 and a record high of 117 °F (47 °C) at East St. Louis, Illinois was recorded in July 1954. Average monthly precipitation ranged from 2.02 inches (51 mm) in January to 4.18 inches (106 mm) in May.