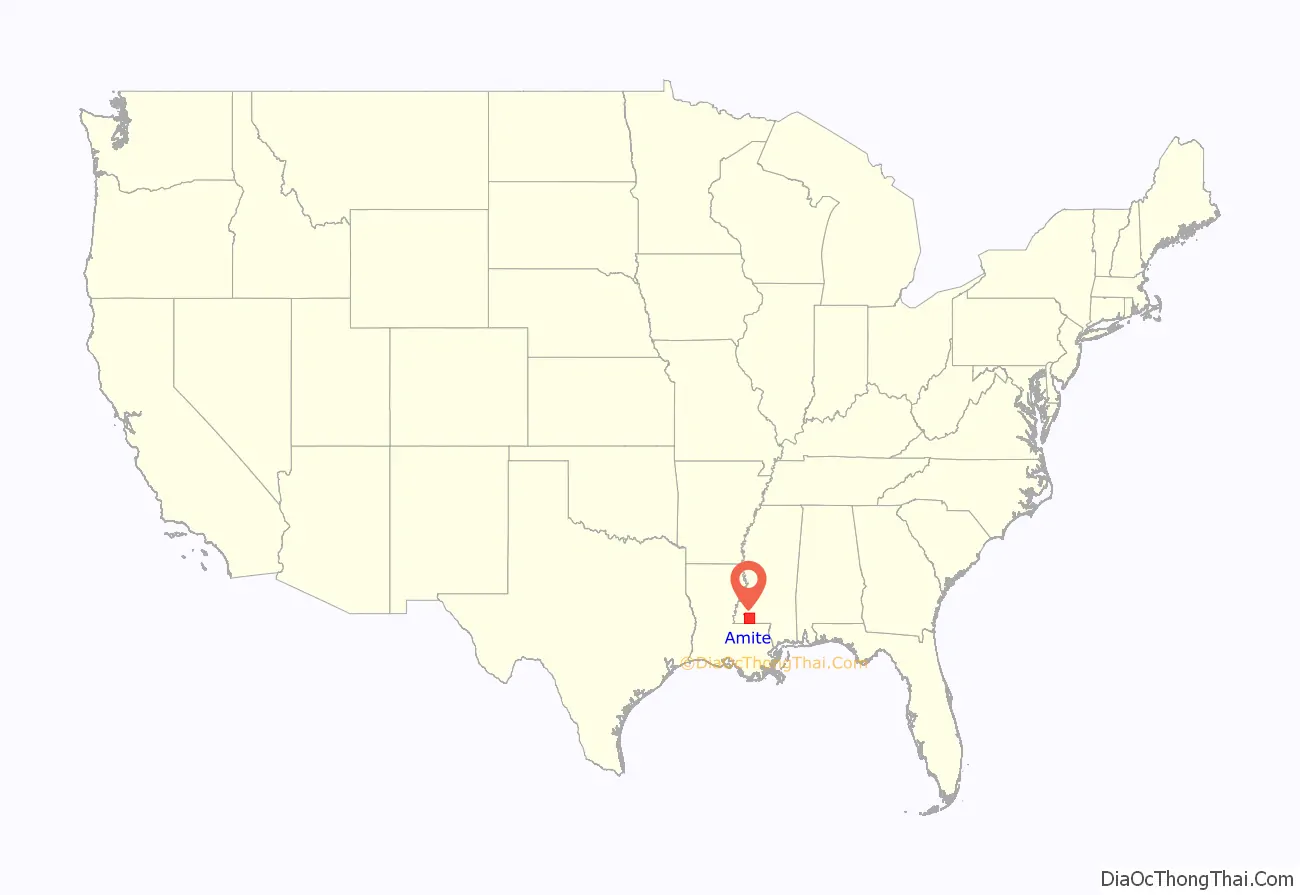

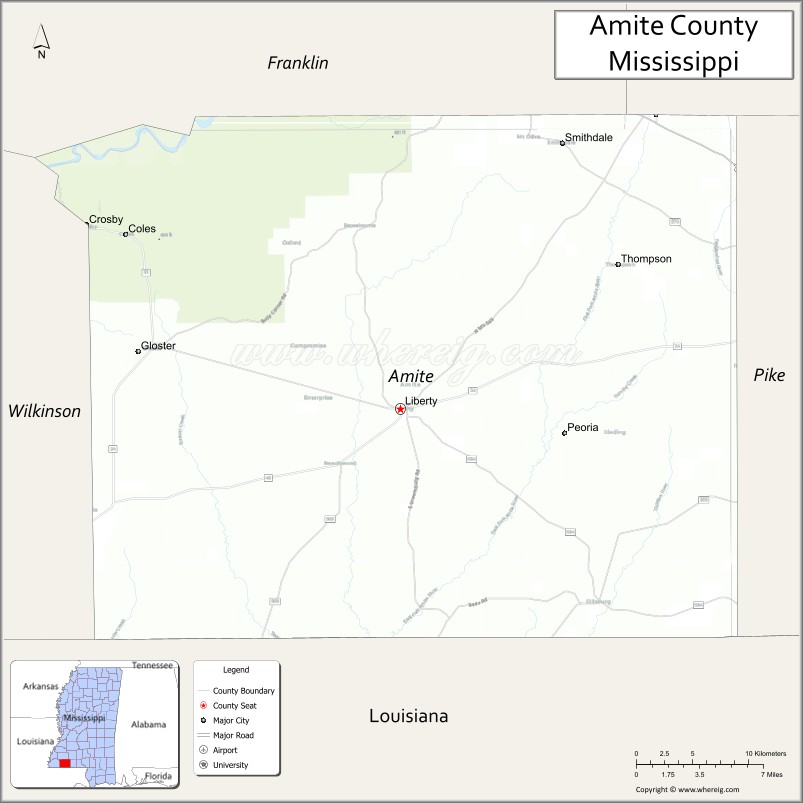

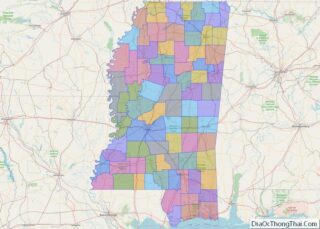

Amite County /ˈeɪ.mɛt/ is a county located in the state of Mississippi on its southern border with Louisiana. As of the 2020 census, the population was 12,720. Its county seat is Liberty. The county is named after the Amite River, which runs through the county.

Amite County is part of the McComb, MS micropolitan statistical area.

| Name: | Amite County |

|---|---|

| FIPS code: | 28-005 |

| State: | Mississippi |

| Founded: | 1809 |

| Named for: | Amite River |

| Seat: | Liberty |

| Largest town: | Gloster |

| Total Area: | 736 sq mi (1,910 km²) |

| Land Area: | 730 sq mi (1,900 km²) |

| Total Population: | 12,720 |

| Population Density: | 17/sq mi (6.7/km²) |

| Time zone: | UTC−6 (Central) |

| Summer Time Zone (DST): | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Website: | www.amitecounty.ms |

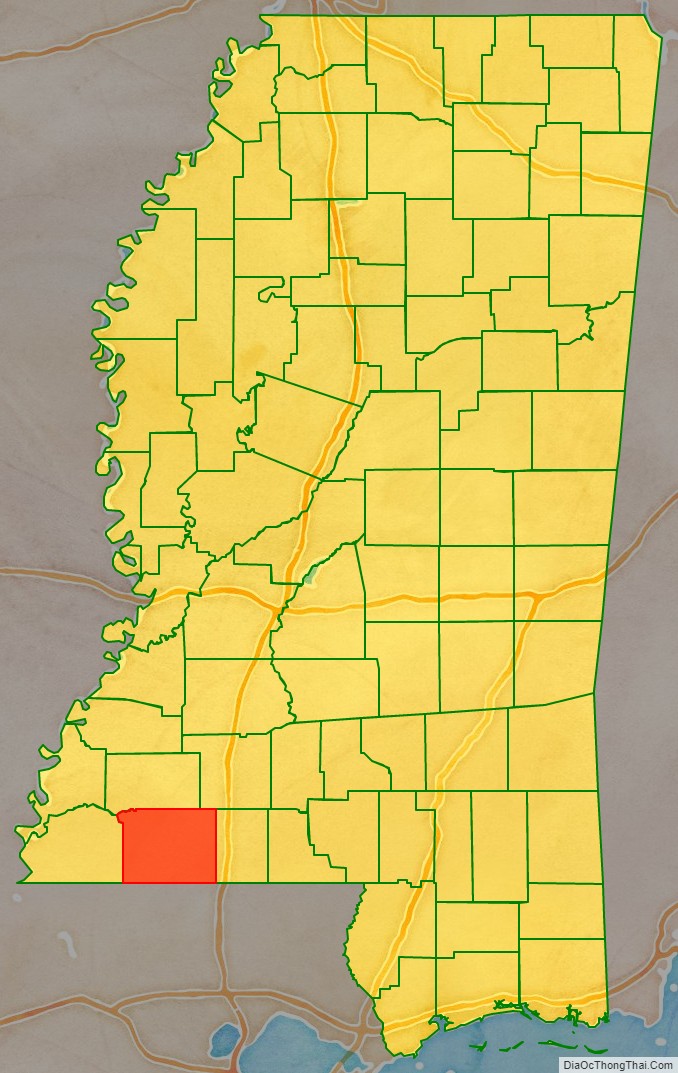

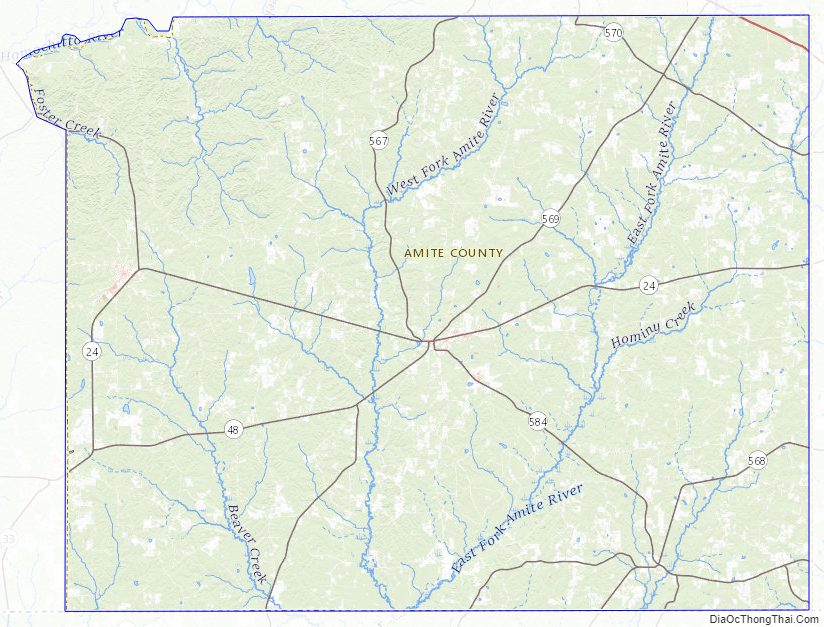

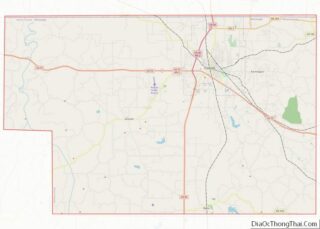

Amite County location map. Where is Amite County?

History

Amite County was established in February 1809 from the eastern portion of Wilkinson County. It was named after the Amite River. French explorers had named the latter for the friendly (amitié in French) indigenous Houma people they encountered in the region.

The legislation that established the county authorized the appointment of five commissioners to find a site for the county seat, near the county’s center and near a good spring; its name was to be Liberty. At this time, the total population of the county numbered about 4000 people, about 80% of whom were middle-class families of seventeenth-century Virginia stock who had gradually migrated through other frontier states. Primary religious groups were all Protestant, including Baptists, Presbyterians, and Methodists.

Completed in 1840, the courthouse in Liberty is the oldest courthouse in Mississippi in continuous use. Liberty eventually became the county’s justice and business center. The county economy was based on timber from longleaf pine and the cultivation of commodity crops of cotton, indigo, and tobacco, usually on plantations worked by enslaved African Americans. Given the reliance of planters on labor-intensive crops such as tobacco and cotton, the county soon had a majority population of enslaved African Americans. Even in the antebellum period, the county seat attracted entertainers and lecturers on tour. In the 1850s, Liberty hosted opera singer Jenny Lind, known as the “Swedish Nightingale,” at the Walsh building.

In 1861, the state legislature called a convention to vote on secession from the United States. David Hurst, the delegate from Amite County, voted against secession, but the majority of the state’s delegates voted for it. Led by South Carolina, the largest slave-owning states were the first in the South to secede. Mississippi voted to join the Confederate States of America. During the Civil War, Captain George H. Tichenor married Margaret Anne Drane at the Liberty Baptist Church; Tichenor developed an antiseptic to treat wounds suffered by soldiers in the war. By the end of the war, 279 men from Amite County had died for the Confederate cause. Amite County was not in a theater of war.

A raiding party of Union cavalry, under the command of Colonel Benjamin Grierson, is known to have camped in the county nine miles east of Liberty on the evening of April 28, 1863, while conducting a deep penetration raid as part of the Vicksburg Campaign. As part of that raid, Union forces pillages many homes and plantations. Most of the buildings of the Amite Female Seminary, with 13 pianos, were burnt; one building was spared, the small Mary Van Norman Ratcliff Building, commonly known as the “Little Red Schoolhouse.”

At the end of the Civil War, Amite County’s population was 60% African American. During Reconstruction, freedmen elected several African Americans to local office as county sheriff. After Reconstruction, white Democrats regained power in the state legislature through a combination of violent voter repression and fraud. They disenfranchised most African Americans and many poor whites in the state by the new 1890 state constitution, which imposed a poll tax, literacy tests, and other requirements as barriers to voter registration. These were administered by whites in a discriminatory way. Most black voters and many poor whites were dropped from the voter rolls.

20th century to present

Racial violence, including lynchings, escalated during the Jim Crow years. The county had 14 documented lynchings in the period from 1877 to 1950; most took place around the turn of the century when disenfranchisement and imposition of Jim Crow was underway.

Blacks were excluded from the political process in the county and state until the late 1960s. African Americans were a majority in the state until the 1930s but excluded from voting, they were also excluded from juries and the entire political system.

The county continued to be based on agriculture, with cotton the basis of the economy into the 1930s. A boll weevil invasion damaged many cotton crops. Planters shifted to logging and dairy farming in the 1930s, during the Great Depression.

As agriculture was mechanized, reducing the need for farm labor, many blacks left Amite County during the first half of the 20th century in two waves of the Great Migration. In the first wave, before World War II, many moved north to Chicago and other industrial cities of the Midwest. In the second wave, they moved to the West Coast, where the burgeoning defense industry created jobs before, during, and after the war. From 1940 to 1960, the county population declined by 29%, as can be seen on the census tables below. Some rural whites also left the county for industrialized cities.

In the 1950s, local farmer E.W. Steptoe founded a chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in the county. Herbert Lee, a married farmer with nine children, was among its charter members. They were working to regain constitutional civil rights, including the ability to vote. In the summer of 1961, Bob Moses from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee worked in the county to organize African Americans for voter registration. He was beaten by Bill Caston, a cousin to the sheriff, near the county courthouse, and arrested. He was told to leave the county for his own safety. In the 1960s, only one African American of the total of 5,500 in Amite County was a registered voter. Even after the Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965, extensive grassroots efforts were required to register eligible voters.

Racial violence against blacks in the county escalated during the years of the Civil Rights Movement. On September 25, 1961, at the Westbrook Cotton Gin, about a dozen witnesses, both white and black, saw E.H. Hurst, a white state legislator, murder Herbert Lee in broad daylight. At the inquest that day, Hurst claimed self-defense and witnesses, intimidated by the armed white men in the courtroom, supported him. Learning that the federal government might hold a grand jury in the case, Louis Allen, an African-American veteran of World War II and witness to Lee’s murder, talked to the FBI to try to gain protection if he were to testify truthfully to what he saw. They said they could not help him. Whites suspected he had talked with the FBI and began to harass him.

Allen’s business was boycotted by whites, and the veteran was beaten and arrested more than once by the county sheriff. He stayed in the area to help his aging parents, but planned to leave. On January 31, 1964, he was shot and killed on his land. No one was ever prosecuted for Allen’s death. Investigations since 1994 suggest that Allen was killed by Daniel (Danny) Jones, the county sheriff and son of the Ku Klux Klan’s leader in the county. Danny Jones was featured as a likely perpetrator in the Allen case, in a 2011 episode of 60 Minutes focusing on civil rights cold cases, but he denied an interview. He died in 2012 or 2013.

Following the repression of the civil rights era and a continuing poor economy, younger African Americans continued to leave the county, seeking jobs in bigger cities. The population declined more than 11 percent from 1960 to 1970, and further declines occurred to 1980 (see census tables below.) Because of the murders of Lee and Allen, voter registration efforts had stopped in the early 1960s. African Americans did not register until after passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which provided federal protection and oversight. Today the county is majority white in population.

Noted historic sites listed on the National Register of Historic Places include the Amite County Courthouse and the Westbrook Cotton Gin, the only one surviving of seven in the county. In addition, 19th-century plantation houses and the Liberty and Bethany Presbyterian churches are listed on the Register.

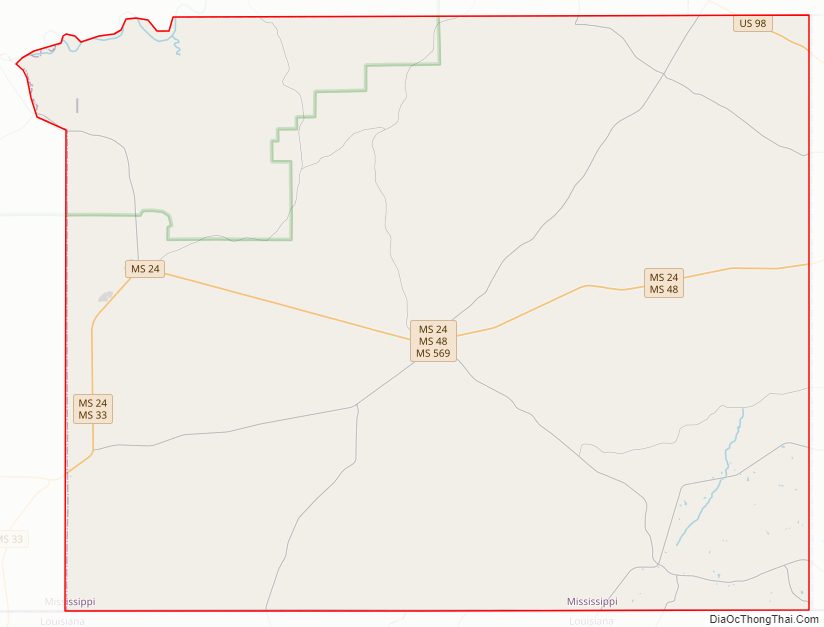

Amite County Road Map

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 732 square miles (1,900 km), of which 730 square miles (1,900 km) is land and 1.5 square miles (3.9 km) (0.2%) is water.

Major highways

- U.S. Highway 98

- Mississippi Highway 24

- Mississippi Highway 33

- Mississippi Highway 48

- Mississippi Highway 569

- Mississippi Highway 570

- Mississippi Highway 567

- Mississippi Highway 568

- Mississippi Highway 571

- Mississippi Highway 584

Adjacent counties

- Franklin County (north)

- Lincoln County (northeast)

- Pike County (east)

- Tangipahoa Parish, Louisiana (southeast)

- St. Helena Parish, Louisiana (south)

- East Feliciana Parish, Louisiana (southwest)

- Wilkinson County (west)

National protected area

- Homochitto National Forest (part)

State protected area

- Ethel Stratton Vance Natural Area

Flora and fauna

The flora of Amite County includes about 1000 species of vascular plants.

Illicium floridanum, Florida anise or stinkbush, a plant species endemic to the southeastern U.S.

Bottomland mixed hardwood-spruce pine forest along the West Fork Amite River

Stewartia malacodendron, or silky camellia, an uncommon species of the southeastern U.S.