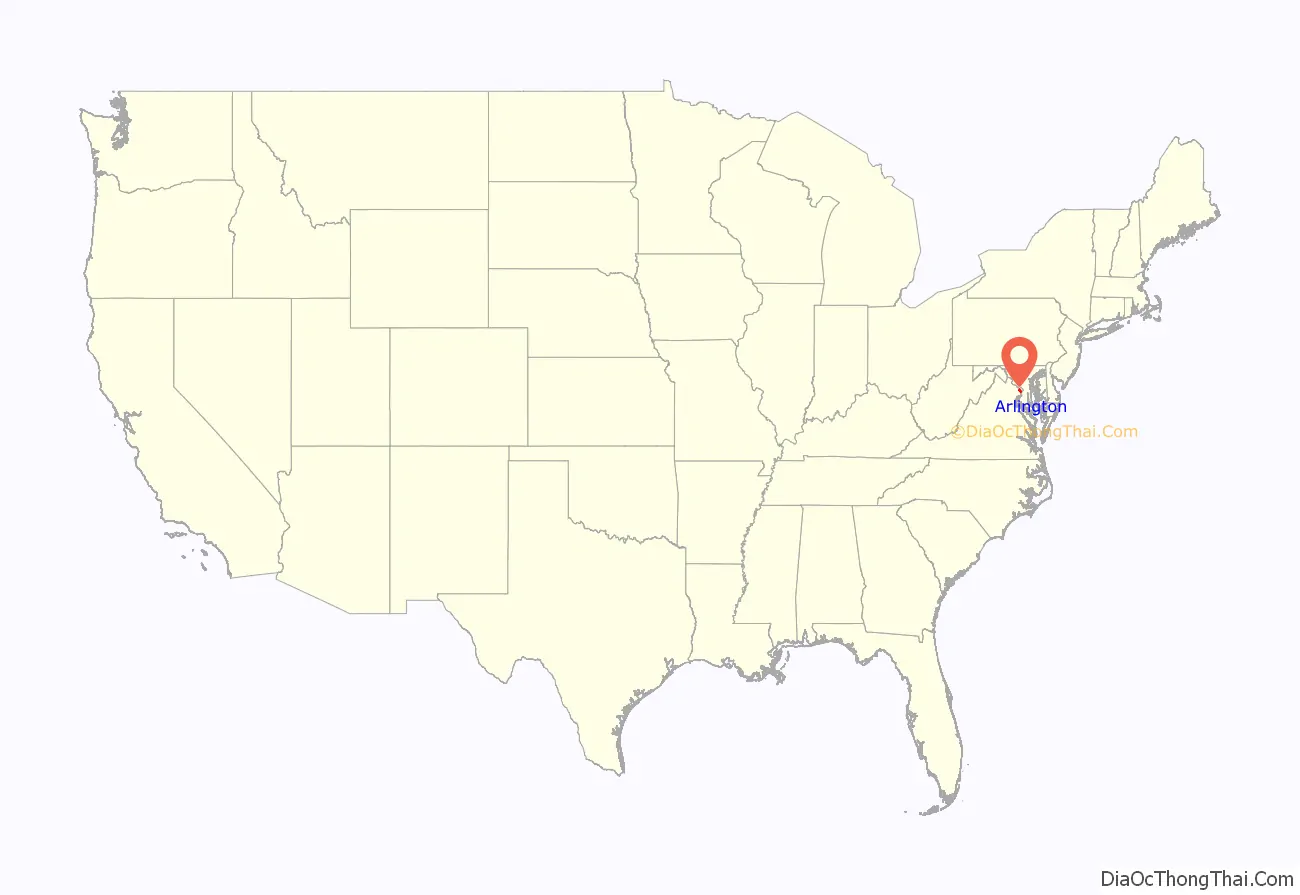

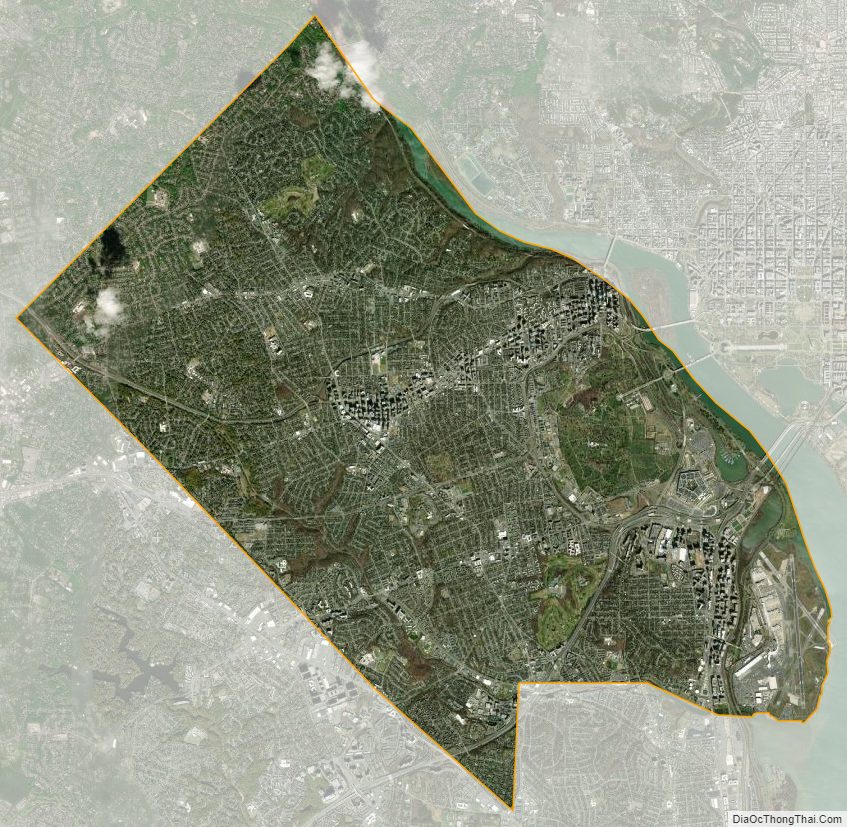

Arlington County is a county in the U.S. state of Virginia. The county is located in Northern Virginia on the southwestern bank of the Potomac River directly across from Washington, D.C.. The county is coextensive with the U.S. Census Bureau’s census-designated place of Arlington. Arlington County is the second-largest city in the Washington metropolitan area, although it does not have the legal designation of an independent city or incorporated town under Virginia state law.

In 2020, the county’s population was estimated at 238,643, making Arlington County the sixth-largest county in Virginia by population and the largest unincorporated community in the United States. If Arlington County were incorporated as a city, it would be the third-most populous city in Virginia. With a land area of 26 square miles (67 km), Arlington is the geographically smallest self-governing county in the U.S. but has no incorporated towns under state law. It has the fifth-highest income per capita among all U.S. counties, and is the nation’s 11th-most densely populated county.

Arlington is home to the Pentagon (headquarters of the U.S. Department of Defense), the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), Reagan National Airport, and Arlington National Cemetery. In academia, the county contains Marymount University, the satellite campuses and research programs of George Mason University’s Antonin Scalia Law School, Schar School of Policy and Government, and the Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution, as well as graduate programs, research, and non-traditional student education centers at the University of Virginia and Virginia Tech. Arlington is also the future home of the co-headquarters of Amazon, and the global headquarters of aerospace manufacturing and defense industry giants Boeing and Raytheon Technologies, as well as the American subsidiary of BAE Systems.

| Name: | Arlington County |

|---|---|

| FIPS code: | 51-013 |

| State: | Virginia |

| Founded: | February 27, 1801 |

| Named for: | Arlington House |

| Total Area: | 26 sq mi (70 km²) |

| Land Area: | 26 sq mi (70 km²) |

| Total Population: | 238,643 |

| Population Density: | 9,200/sq mi (3,500/km²) |

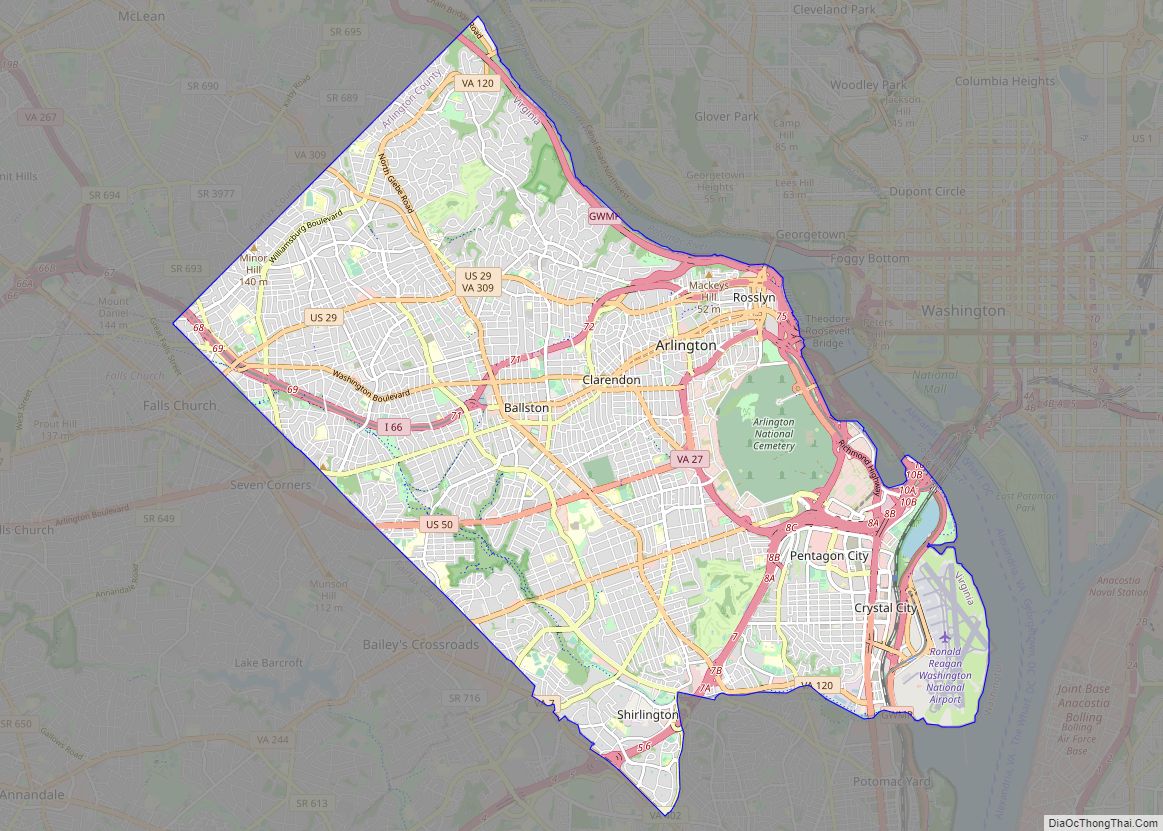

Arlington County location map. Where is Arlington County?

History

Colonial Virginia

The area that now constitutes Arlington County had been part of Fairfax County in the Colony of Virginia. Land grants from the British monarch were awarded to prominent Englishmen in exchange for political favors and efforts at development. One of the grantees was Thomas Fairfax for whom both Fairfax County and the City of Fairfax are named. The county’s name of Arlington comes from Henry Bennet, Earl of Arlington, a plantation along the Potomac River, and Arlington House, the family residence on that property. George Washington Parke Custis, grandson of First Lady Martha Washington, acquired this land in 1802. The estate was eventually passed down to Mary Anna Custis Lee, wife of General Robert E. Lee. The property later became Arlington National Cemetery during the Civil War.

District of Columbia

The area that now includes almost all of Arlington County, along with most of what is present-day Alexandria, was ceded to the new federal government by Virginia. With the passage of the Residence Act in 1790, Congress approved a new permanent capital to be located on the Potomac River, the exact area to be selected by U.S. President George Washington. The Residence Act originally only allowed the President to select a location in Maryland as far east as what is now the Anacostia River. However, President George Washington shifted the federal territory’s borders to the southeast in order to include the existing town of Alexandria at the district’s southern tip.

In 1791, Congress, at Washington’s request, amended the Residence Act to approve the new site, including the territory ceded by Virginia. However, this amendment to the Residence Act specifically prohibited the “erection of the public buildings otherwise than on the Maryland side of the River Potomac.”

As permitted by the United States Constitution, the initial shape of the federal district was a square, measuring 10 miles (16 km) on each side, totaling 100 square miles (260 km). During 1791–92, Andrew Ellicott and several assistants placed boundary stones at every mile point. Fourteen of these markers were in Virginia and many of the stones are still standing.

When Congress arrived in the new capital, they passed the Organic Act of 1801 to officially organize the District of Columbia and placed the entire federal territory, including the cities of Washington, Georgetown, and Alexandria, under the exclusive control of Congress. Further, the territory within the District was organized into two counties: the County of Washington to the east of the Potomac and the County of Alexandria to the west. It included almost all of the present Arlington County, plus part of what is now the independent city of Alexandria. This Act formally established the borders of the area that would eventually become Arlington but the citizens located in the District were no longer considered residents of Maryland or Virginia, thus ending their representation in Congress.

Retrocession

Residents of Alexandria County had expected the federal capital’s location to result in higher land prices and the growth of commerce. Instead the county found itself struggling to compete with the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal at the port of Georgetown, which was farther inland and on the northern side of the Potomac River next to the city of Washington. Members of Congress from other areas of Virginia also used their power to prohibit funding for projects, such as the Alexandria Canal, which would have increased competition with their home districts. In addition, Congress had prohibited the federal government from establishing any offices in Alexandria, which made the county less important to the functioning of the national government.

Alexandria had also been an important center of the slave trade; Franklin and Armfield Office in Alexandria was once an office used in slave trading. Rumors circulated that abolitionists in Congress were attempting to end slavery in the District; such an action would have further depressed Alexandria’s slavery-based economy. At the same time, an active abolitionist movement arose in Virginia that created a division on the question of slavery in the Virginia General Assembly. Pro-slavery Virginians recognized that if Alexandria were returned to Virginia, it could provide two new representatives who favored slavery in the state legislature. (Some time after retrocession, during the American Civil War, this division led to the formation of the state of West Virginia, which comprised by what was then 51 counties in the northwest that favored abolitionism.)

Largely as a result of the economic neglect by Congress, divisions over slavery, and the lack of voting rights for the residents of the District, a movement grew to return Alexandria to Virginia from the District of Columbia. From 1840 to 1846, Alexandrians petitioned Congress and the Virginia legislature to approve this transfer known as retrocession. On February 3, 1846, the Virginia General Assembly agreed to accept the retrocession of Alexandria if Congress approved. Following additional lobbying by Alexandrians, Congress passed legislation on July 9, 1846, to return all the District’s territory south of the Potomac River back to Virginia, pursuant to a referendum; President James K. Polk signed the legislation the next day. A referendum on retrocession was held on September 1–2, 1846. The voters in the City of Alexandria voted in favor of the retrocession, 734 to 116, while those in the rest of Alexandria County voted against retrocession 106 to 29. Pursuant to the referendum, President Polk issued a proclamation of transfer on September 7, 1846. However, the Virginia legislature did not immediately accept the retrocession offer. Virginia legislators were concerned that the people of Alexandria County had not been properly included in the retrocession proceedings. After months of debate, the Virginia General Assembly voted to formally accept the retrocession legislation on March 13, 1847.

In 1852, the Virginia legislature voted to incorporate a portion of Alexandria County to make the City of Alexandria, which until then had been administered only as an unincorporated town within the political boundaries of Alexandria County.

Civil War

During the American Civil War, Virginia seceded from the Union as a result of a statewide referendum held on May 23, 1861; the voters from Alexandria County approved secession by a vote of 958–48. This vote indicates the degree to which its only town, Alexandria, was pro-secession and pro-Confederate. The rural county residents outside the city were Union loyalists and voted against secession.

Although Virginia was part of the Confederacy, the Confederacy did not control all of Northern Virginia. In 1862, the U.S. Congress passed a law that some claimed had required that owners of property in those districts in which the insurrection existed were to pay their real estate taxes in person.

In 1864, during the war, the federal government confiscated the Abingdon estate, which was located on and near the present Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport, when its owner failed to pay the estate’s property tax in person because he was serving in the Confederate Army. The government then sold the property at auction, whereupon the purchaser leased the property to a third party.

After the war ended in 1865, the Abingdon estate’s heir, Alexander Hunter, started a legal action to recover the property. James A. Garfield, a Republican member of the U.S. House of Representatives who had been a brigadier general in the Union Army during the Civil War and who later became the 20th President of the United States, was an attorney on Hunter’s legal team. In 1870, the Supreme Court of the United States, in a precedential ruling, found that the government had illegally confiscated the property and ordered that it be returned to Hunter.

The property containing the home of Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s family at and around Arlington House was subjected to an appraisal of $26,810, on which a tax of $92.07 was assessed. However, Lee’s wife, Mary Anna Custis Lee, the owner of the property, did not pay this tax in person. As a result of the 1862 law, the Federal government confiscated the property and made it into a military cemetery.

After the war ended and after the death of his parents, George Washington Custis Lee, the Lees’ eldest son, initiated a legal action in an attempt to recover the property. In December 1882, the U.S. Supreme Court found that the federal government had illegally confiscated the property without due process and returned the property to Custis Lee while citing the Court’s earlier ruling in the Hunter case. In 1883, the U.S. Congress purchased the property from Lee for its fair market value of $150,000, whereupon the property became a military reservation and eventually Arlington National Cemetery. Although Arlington House is within the National Cemetery, the National Park Service presently administers the House and its grounds as a memorial to Robert E. Lee.

Confederate incursions from Falls Church, Minor’s Hill and Upton’s Hill—then securely in Confederate hands—occurred as far east as the present-day area of Ballston. On August 17, 1861, an armed force of 600 Confederate soldiers engaged the 23rd New York Infantry near that crossroads, killing one. Another large incursion on August 27 involved between 600 and 800 Confederate soldiers, which clashed with Union soldiers at Ball’s Crossroads, Hall’s Hill, and along the modern-day border between the City of Falls Church and Arlington. A number of soldiers on both sides were killed. However, the territory in present-day Arlington was never successfully captured by Confederate forces.

Separation from Alexandria

In 1870, the City of Alexandria became legally separated from Alexandria County by an amendment to the Virginia Constitution that made all Virginia incorporated cities (but not incorporated towns) independent of the counties of which they had previously been a part. Because of the confusion between the city and the county having the same name, a movement started to rename Alexandria County. In 1920, the name Arlington County was adopted, after Arlington House, the home of the American Civil War Confederate general Robert E. Lee, which stands on the grounds of what is now Arlington National Cemetery. The Town of Potomac was incorporated as a town in Alexandria County in 1908. The town was annexed by Alexandria in 1930.

In 1896, an electric trolley line was built from Washington through Ballston, which led to growth in the county (see Northern Virginia trolleys).

20th century

In 1920, the Virginia legislature renamed the area Arlington County to avoid confusion with the City of Alexandria which had become an independent city in 1870 under the new Virginia Constitution adopted after the Civil War.

In the 1930s, Hoover Field was established on the present site of the Pentagon; in that decade, Buckingham, Colonial Village, and other apartment communities also opened. World War II brought a boom to the county, but one that could not be met by new construction due to rationing imposed by the war effort.

In October 1942, not a single rental unit was available in the county. On October 1, 1949, the University of Virginia in Charlottesville created an extension center in the county named Northern Virginia University Center of the University of Virginia. This campus was subsequently renamed University College, then the Northern Virginia Branch of the University of Virginia, thereafter, the George Mason College of the University of Virginia, until it was finally designated George Mason University, which it remains today. The Henry G. Shirley Highway (now Interstate 395) was constructed during World War II, along with adjacent developments such as Shirlington, Fairlington, and Parkfairfax.

In February 1959, Arlington County Schools desegregated racially at Stratford Junior High School (now Dorothy Hamm) with the admission of black pupils Donald Deskins, Michael Jones, Lance Newman, and Gloria Thompson. The U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in 1954, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas had struck down the previous ruling on racial segregation Plessy v. Ferguson that held that facilities could be racially “separate but equal”. Brown v. Board of Education ruled that “racially separate educational facilities were inherently unequal”. The elected Arlington County School Board presumed that the state would defer to localities and in January 1956 announced plans to integrate Arlington schools. The state responded by suspending the county’s right to an elected school board. The Arlington County Board, the ruling body for the county, appointed segregationists to the school board and blocked plans for desegregation. Lawyers for the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) filed suit on behalf of a group of parents of both white and black students to end segregation. Black pupils were still denied admission to white schools, but the lawsuit went before the U.S. District Court, which ruled that Arlington schools were to be desegregated by the 1958–59 academic year. In January 1959 both the U.S. District Court and the Virginia Supreme Court had ruled against Virginia’s massive resistance movement, which opposed racial integration. The Arlington County Central Library’s collections include written materials as well as accounts in its Oral History Project of the desegregation struggle in the county.

Arlington during the 1960s underwent tremendous change after the huge influx of newcomers in the 1950s. M.T. Broyhill & Sons Corporation was at the forefront of building the new communities for these newcomers, which would lead to the election of Joel Broyhill as the representative of Virginia’s 10th congressional district for 11 terms. The old commercial districts did not have ample off-street parking and many shoppers were taking their business to new commercial centers, such as Parkington and Seven Corners. Suburbs further out in Virginia and Maryland were expanding, and Arlington’s main commercial center in Clarendon was declining, similar to what happened in other downtown centers. With the growth of these other suburbs, some planners and politicians pushed for highway expansion. The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 would have enabled that expansion in Arlington. However, he administrator of the National Capital Transportation Agency, economist C. Darwin Stolzenbach, saw the benefits of rapid transit for the region and oversaw plans for a below ground rapid transit system, now the Washington Metro, which included two lines in Arlington. Initial plans called for what became the Orange Line to parallel I-66, which would have mainly benefited Fairfax County. Arlington County officials called for the stations in Arlington to be placed along the decaying commercial corridor between Rosslyn and Ballston that included Clarendon. A new regional transportation planning entity was formed, the Washington Metropolitan Transit Authority. Arlington officials renewed their push for a route that benefited the commercial corridor along Wilson Boulevard, which prevailed. There were neighborhood concerns that there would be high-density development along the corridor that would disrupt the character of old neighborhoods. With the population in the county declining, political leaders saw economic development as a long-range benefit. Citizen input and county planners came up with a workable compromise, with some limits on development. The two lines in Arlington were inaugurated in 1977. The Orange Line’s creation was more problematic than the Blue Line’s. The Blue Line served the Pentagon and National Airport and boosted the commercial development of Crystal City and Pentagon City. Property values along the Metro lines increased significantly for both residential and commercial property. The ensuing gentrification caused the mostly working and lower middle class white Southern residents to either be priced out of rent or in some cases sell their homes. This permanently changed the character of the city, and ultimately resulted in the virtual eradication of this group over the coming 30 years, being replaced with an increasing presence of a white-collar transplant population mostly of Northern stock. While a population of white-collar government transplant workers had always been present in the county, particularly in its far northern areas and in Lyon Village, the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s saw the complete dominance of this group over the majority of Arlington’s residential neighborhoods, and mostly economically eliminated the former working-class residents of areas such as Cherrydale, Lyon Park, Rosslyn, Virginia Square, Claremont, and Arlington Forest, among other neighborhoods. The transformation of Clarendon is particularly striking. This neighborhood, a downtown shopping area, fell into decay. It became home to a vibrant Vietnamese business community in the 1970s and 1980s known as Little Saigon. It has now been significantly gentrified. Its Vietnamese population is now barely visible, except for several holdout businesses. Arlington’s careful planning for the Metro has transformed the county and has become a model revitalization for older suburbs.

In 1965, after years of negotiations, Arlington swapped some land in the south end with Alexandria, though less than originally planned. The land was located along King Street and Four Mile Run. The exchange allowed the two jurisdictions to straighten out the boundary and helped highway and sewer projects to go forward. It moved into Arlington several acres of land to the south of the old county line that had not been a part of the District of Columbia.

21st century

On September 11, 2001, five al-Qaeda hijackers deliberately crashed American Airlines Flight 77 into the Pentagon, killing 115 Pentagon employees and 10 contractors in the building, as well as all 53 passengers, six crew members, and five hijackers on board the aircraft.

Arlington, regarded as a model of smart growth, has experienced explosive growth in the early 21st century.

The Turnberry Tower, located in the Rosslyn neighborhood, was completed in 2009. At the time of completion, the Turnberry Tower was the tallest residential building in the Washington metropolitan area.

In 2017, Nestle USA chose 1812 N Moore in Rosslyn as their US headquarters.

In 2018, Amazon.com, Inc. announced that it would build its co-headquarters in the Crystal City neighborhood, anchoring a broader area of Arlington and Alexandria that was simultaneously rebranded as National Landing.

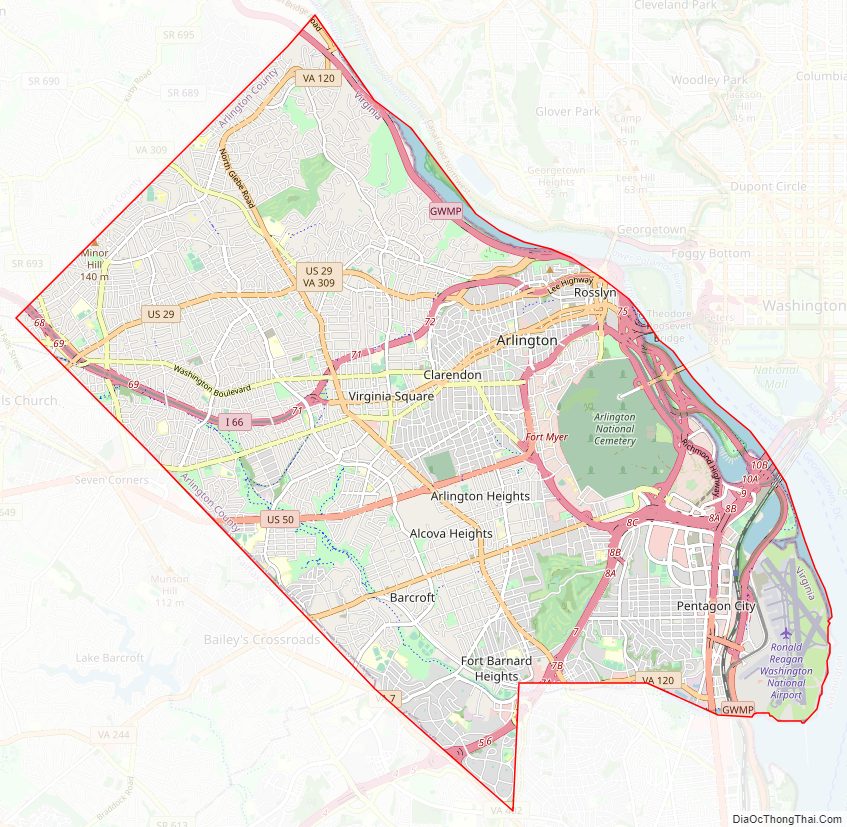

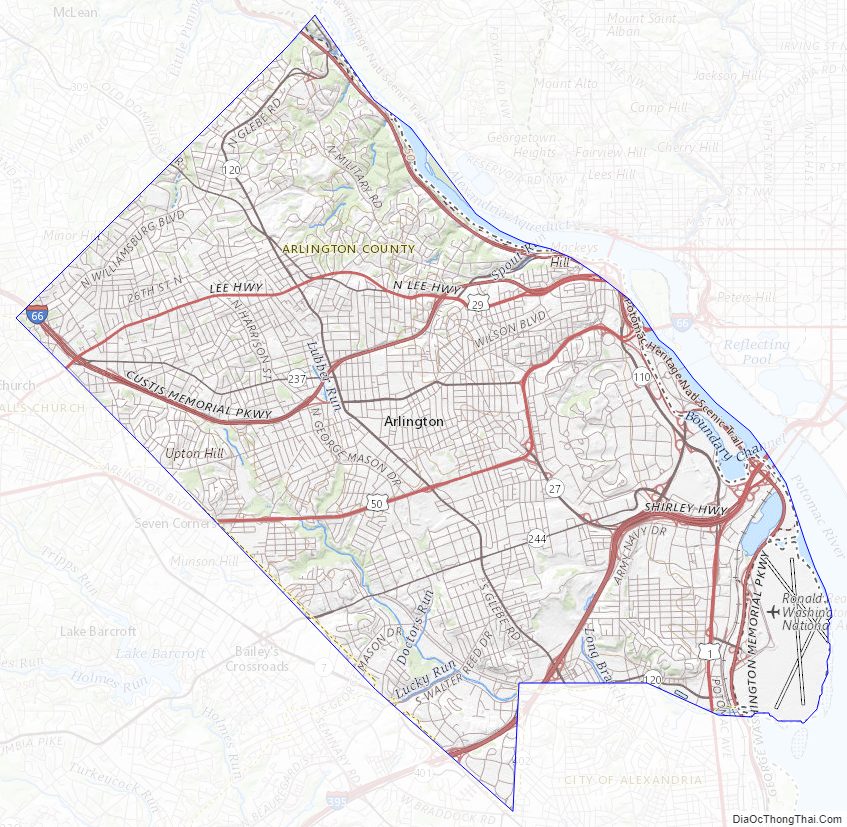

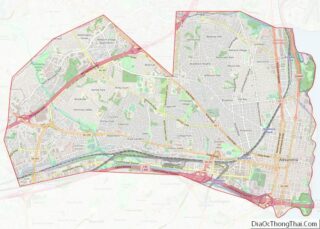

Arlington County Road Map

Geography

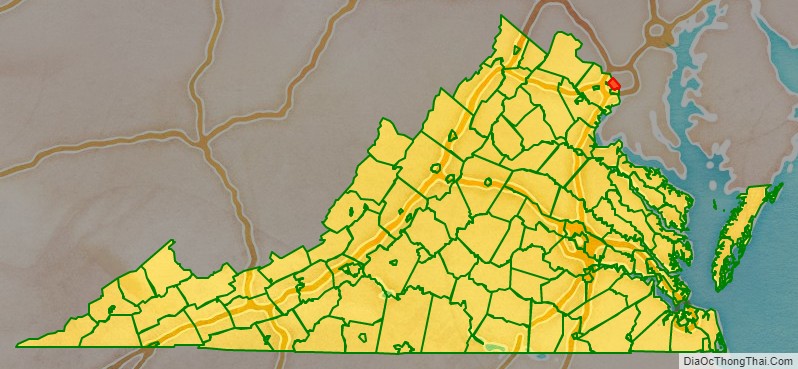

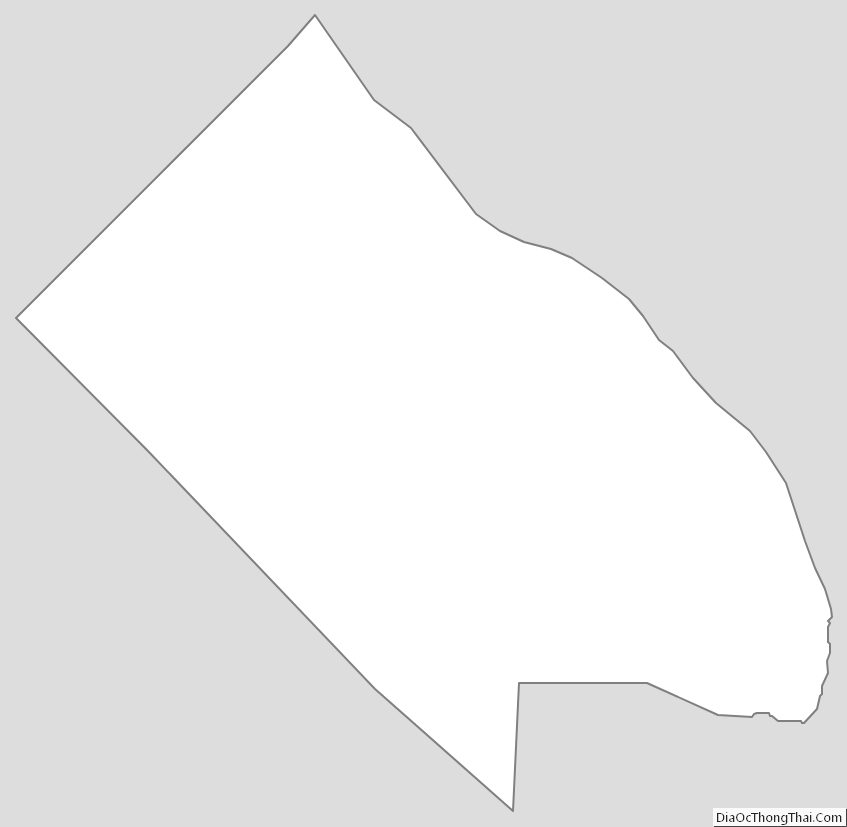

Arlington County is located in northeast Virginia and is surrounded by Fairfax County and Falls Church to the west, the city of Alexandria to the southeast, and Washington, D.C., to the northeast directly across the Potomac River, which forms the county’s northern border. Other landforms also form county borders, particularly Minor’s Hill and Upton’s Hill on the west.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 26.1 square miles (67.6 km), of which 26.0 square miles (67.3 km) is land and 0.1 square miles (0.3 km) (0.4%) is water. It is the smallest county by area in Virginia and is the smallest self-governing county in the United States. About 4.6 square miles (11.9 km) (17.6%) of the county is federal property. The county courthouse and most government offices are located in the Courthouse neighborhood.

For over 30 years, the government has pursued a development strategy of concentrating much of its new development near transit facilities, such as Metrorail stations and the high-volume bus lines of Columbia Pike. Within the transit areas, the government has a policy of encouraging mixed-use and pedestrian- and transit-oriented development. Some of these “urban village” communities include:

- Aurora Highlands

- Ballston

- Barcroft

- Bluemont

- Broyhill Heights

- Claremont

- Clarendon

- Courthouse

- Crystal City

- Glencarlyn

- Greenbrier

- High View Park (formerly Halls Hill)

- Lyon Village

- Palisades

- Pentagon City

- Penrose

- Radnor – Fort Myer Heights

- Rosslyn

- Shirlington

- Virginia Square

- Waycroft-Woodlawn (formerly Woodlawn Park)

- Westover

- Williamsburg Circle

In 2002, Arlington received the EPA’s National Award for Smart Growth Achievement for “Overall Excellence in Smart Growth.” In 2005, the County implemented an affordable housing ordinance that requires most developers to contribute significant affordable housing resources, either in units or through a cash contribution, in order to obtain the highest allowable amounts of increased building density in new development projects, most of which are planned near Metrorail station areas.

A number of the county’s residential neighborhoods and larger garden-style apartment complexes are listed in the National Register of Historic Places and/or designated under the County government’s zoning ordinance as local historic preservation districts. These include Arlington Village, Arlington Forest, Ashton Heights, Buckingham, Cherrydale, Claremont, Colonial Village, Fairlington, Lyon Park, Lyon Village, Maywood, Nauck, Penrose, Waverly Hills and Westover. Many of Arlington County’s neighborhoods participate in the Arlington County government’s Neighborhood Conservation Program (NCP). Each of these neighborhoods has a Neighborhood Conservation Plan that describes the neighborhood’s characteristics, history and recommendations for capital improvement projects that the County government funds through the NCP.

Arlington is often spoken of as divided between North Arlington and South Arlington, which designate the sections of the county that lie north and south of Arlington Boulevard. Places in Arlington are often identified by their location in one or the other. Much consideration is given to socioeconomic and demographic differences between these two portions of the county and the respective amounts of attention they receive in the way of public services.

Arlington ranks fourth in the nation, immediately after Washington, D.C., itself, for park access and quality in the 2018 ParkScore ranking of the top 100 park systems across the United States, according to the ranking methodologies of the nonpartisan Trust for Public Land.

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers, mild to moderately cold winters, and pleasant spring and fall seasons. Arlington averages 41.82 inches of precipitation that is fairly evenly spread out during the year. Snowfall averages 13.7 inches per year. The snowiest months are January and February, although snow also falls in December and March; scarce snow may fall in November or April. The county usually has 60 nights with lows below freezing and 40 days with highs in the 90s. Hundred degree temperatures readings are rare, even more so negative temperature readings, last occurring August 13, 2016 and January 19, 1994, respectively. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Arlington County has a slightly colder version of the humid subtropical climate, abbreviated “Cfa” on climate maps.