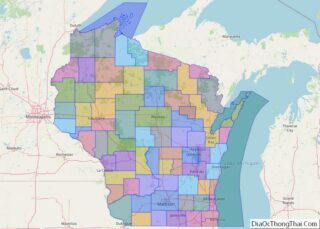

Door County is the easternmost county in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. As of the 2020 census, the population was 30,066. Its county seat is Sturgeon Bay. It is named after the strait between the Door Peninsula and Washington Island. The dangerous passage, known as Death’s Door, contains shipwrecks and was known to Native Americans and early French explorers. The county was created in 1851 and organized in 1861. Nicknamed the “Cape Cod of the Midwest,” Door County is a popular Upper Midwest vacation destination. It is also home to a small Walloon population.

| Name: | Door County |

|---|---|

| FIPS code: | 55-029 |

| State: | Wisconsin |

| Founded: | 1851 |

| Named for: | Porte des Morts |

| Seat: | Sturgeon Bay |

| Largest city: | Sturgeon Bay |

| Total Area: | 2,370 sq mi (6,100 km²) |

| Land Area: | 482 sq mi (1,250 km²) |

| Total Population: | 30,066 |

| Population Density: | 62.4/sq mi (24.1/km²) |

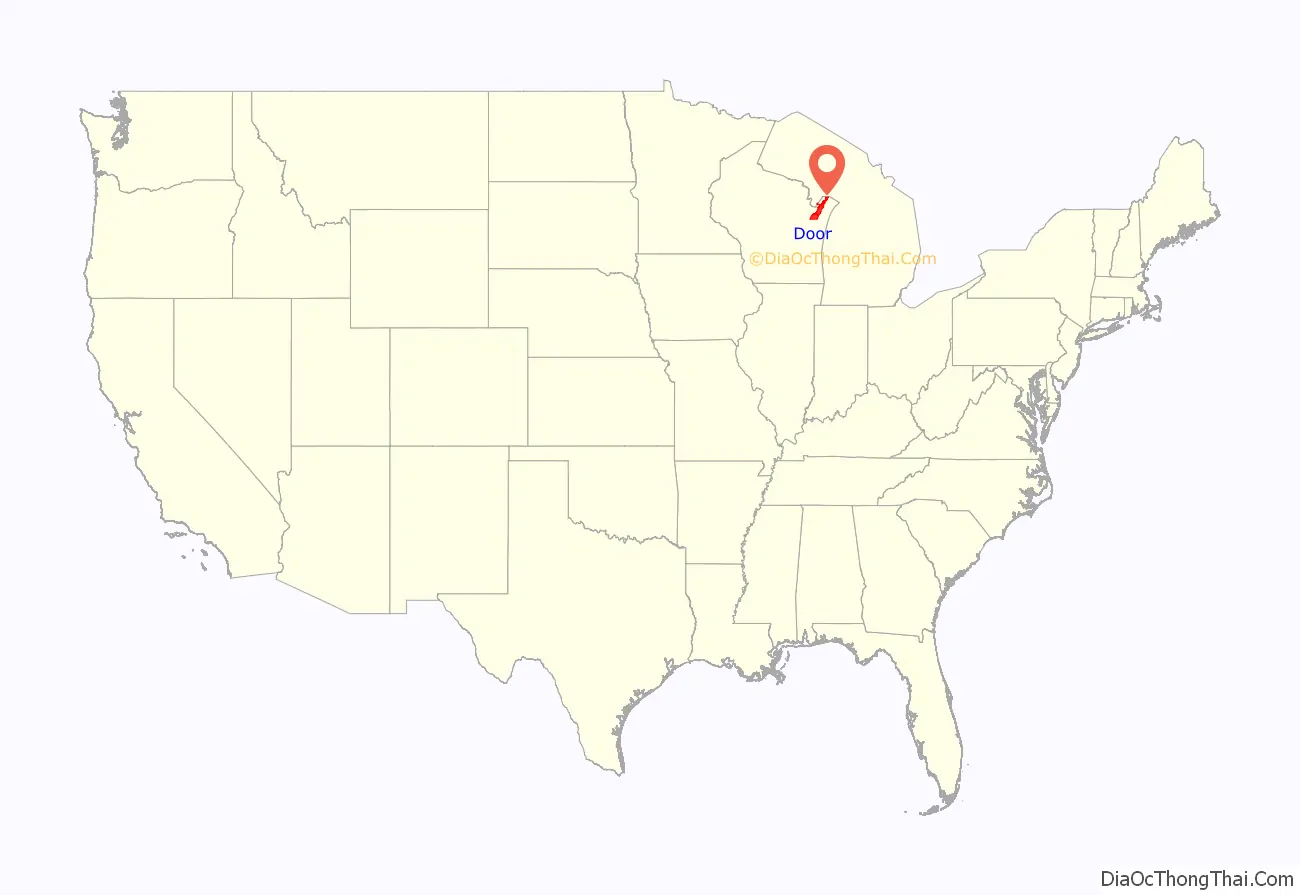

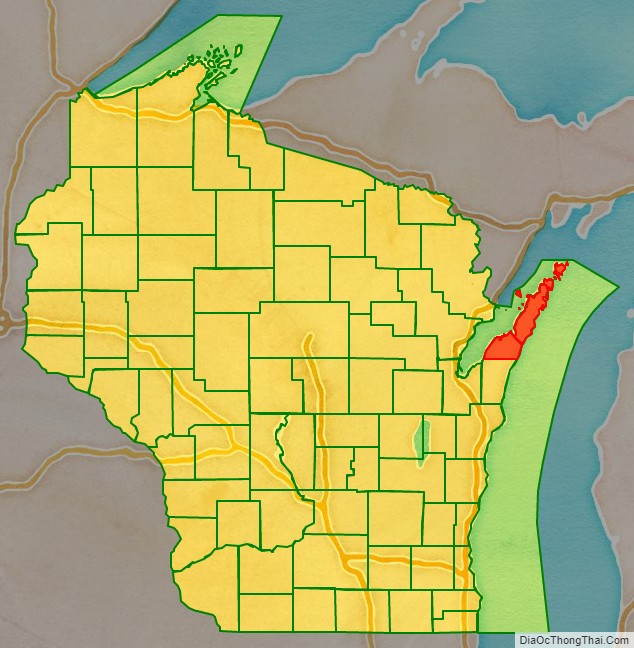

Door County location map. Where is Door County?

History

Native Americans and French

Door County’s name came from Porte des Morts (“Death’s Door”), the passage between the tip of Door Peninsula and Washington Island. The name “Death’s Door” came from Native American tales, heard by early French explorers and published in greatly embellished form by Hjalmar Holand, which described a failed raid by the Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) tribe to capture Washington Island from the rival Pottawatomi tribe in the early 1600s. It has become associated with shipwrecks within the passage. The earliest known written reference to the legend is from Emmanuel Crespel [fr], who termed the peninsula “Cap a la Mort” in 1728.

Settlement and development

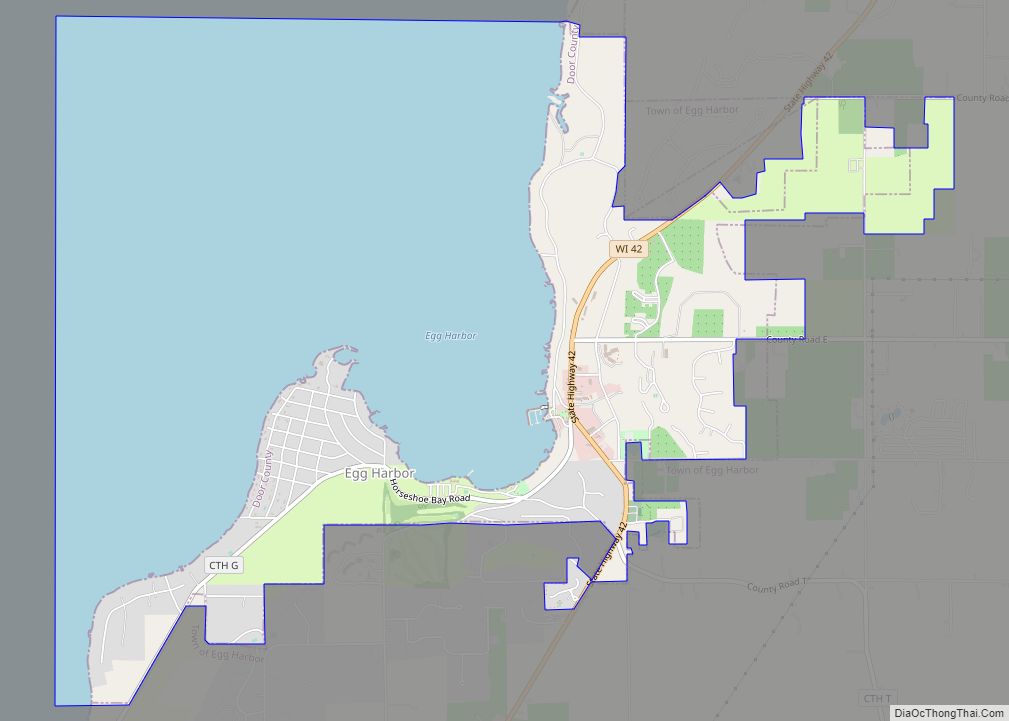

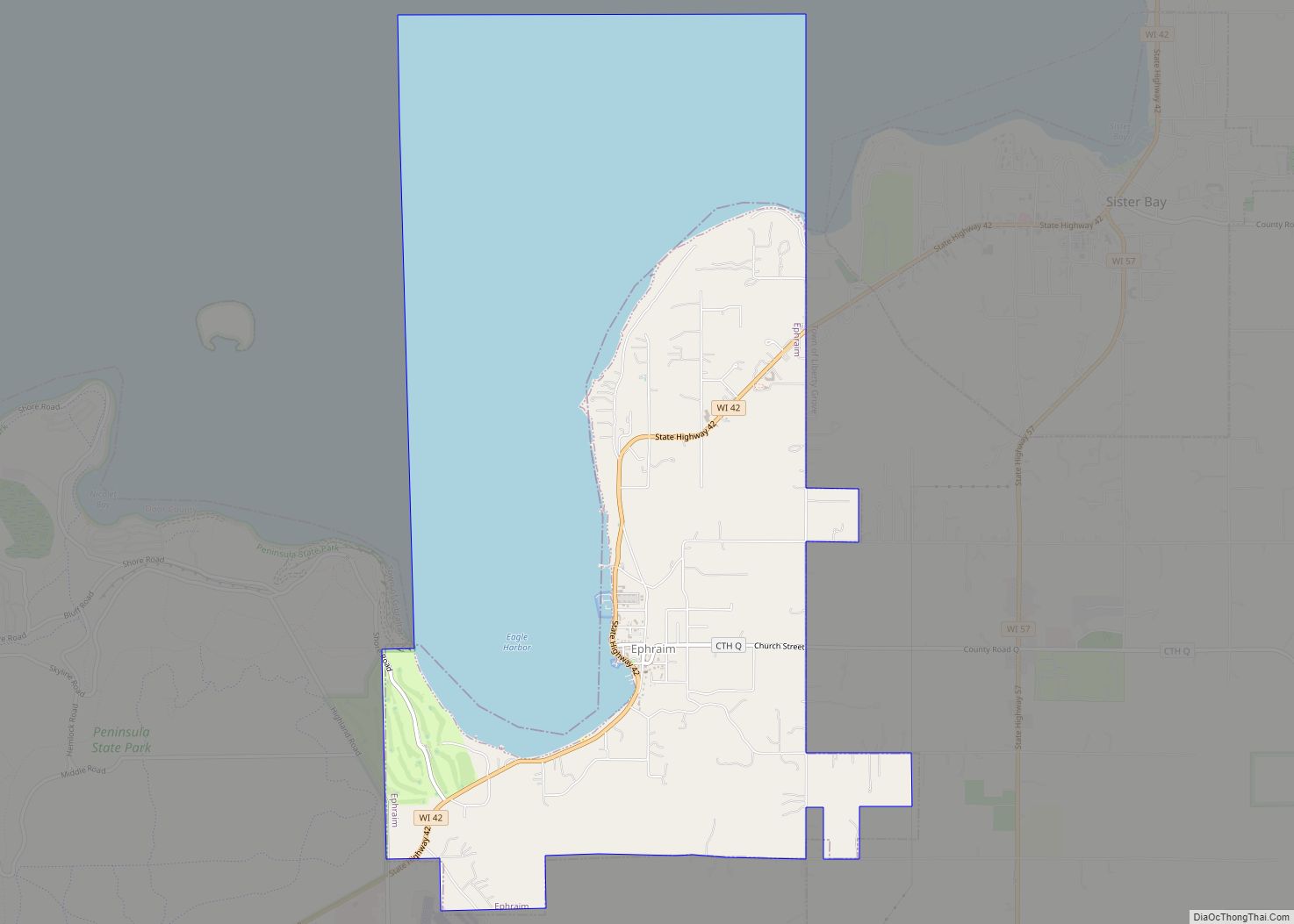

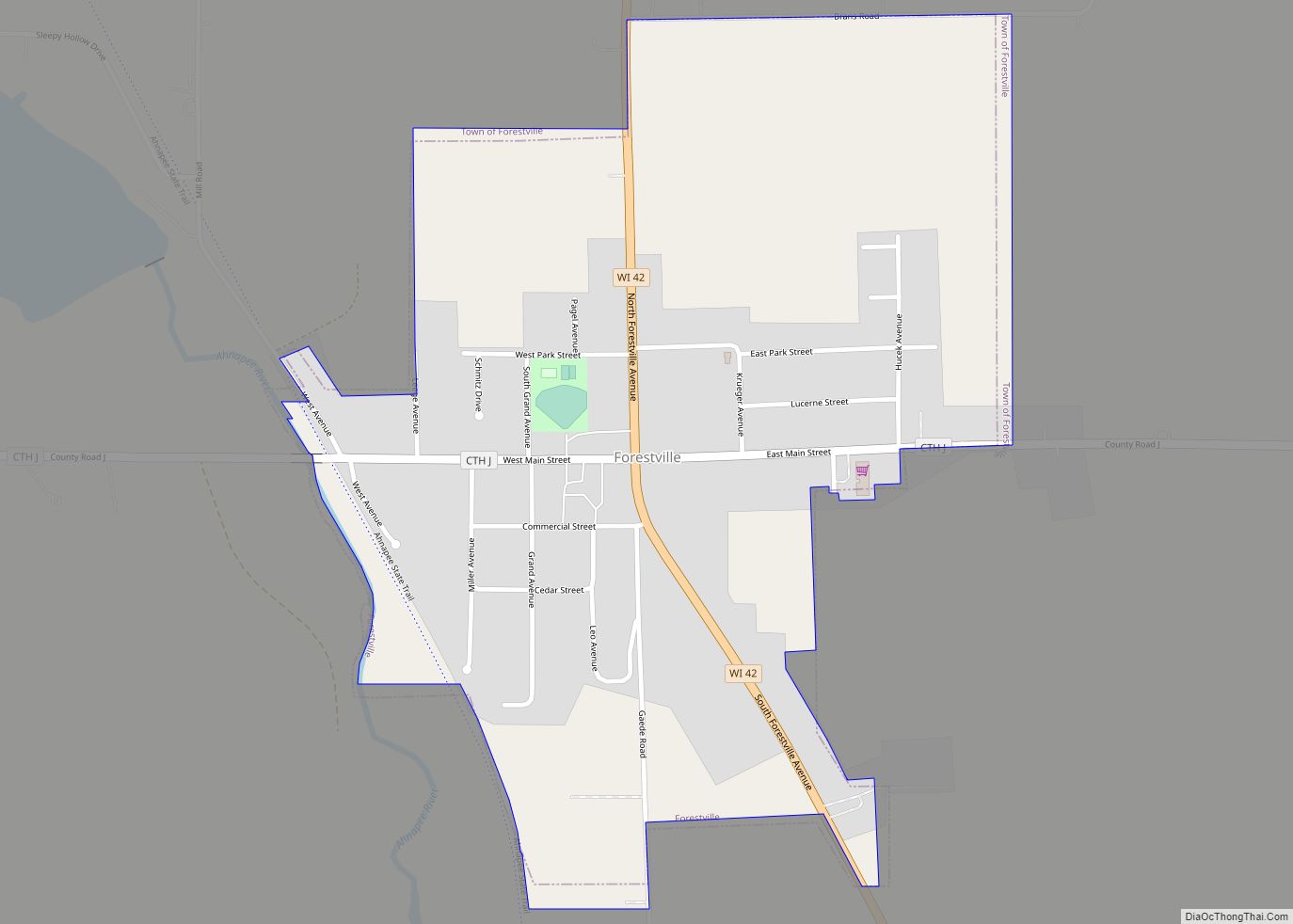

The 19th and 20th centuries saw the immigration and settlement of pioneers, mariners, fishermen, loggers, and farmers. The first white settler was Increase Claflin. In 1834, a federal government-operated quarry operation at the mouth of Sturgeon Bay shipped its first stone blocks; they were used for a harbor breakwater in Michigan City, Indiana. In 1851, Door County was separated from what had been Brown County. In 1853, Moravians founded Ephraim after Nils Otto Tank resisted attempts at land ownership reform at the old religious colony near Green Bay. An African-American community and congregation worshiping at West Harbor on Washington Island was described in 1854. Also in 1854 the first post office in the county opened, on Washington Island. In 1855, four Irishmen were accidentally left behind by their steamboat, leading to the settlement of what is now Forestville. In the 19th century, a fairly large-scale immigration of Belgian Walloons populated a small region in the southern portion of the county, including the area designated as the Namur Historic District. They built small roadside votive chapels, some still in use today, and brought other traditions over from Europe such as the Kermiss harvest festival.

Shortly after the 1831 Treaty of Washington, the federal government surveyed what is now Door County to determine the value of the timber and to divide up parcels for eventual sale. Following the treaty, land in what is now the county was sold or granted to private citizens. Lots from 40 to 320 acres (16 to 129 ha) were sold at 50 cents an acre. From 1841 to 1932, 1,661 land patents were issued to private citizens. Of these, 774 were bounty-land warrants to veterans authorized by the Scrip Warrant Acts of 1842, 1850, 1852, and 1855. The other patents concerned the sale of land: 711 patents were filed under the Land Act of 1820, 139 patents were filed under the Homestead Act of 1862, and 37 patents were filed under the Morrill Act of 1862.

At the time the Homestead Act of 1862 was passed, most of the county’s nearly 2,000 farmers were squatters earning most of their revenue from lumber and wood products. The most common product was cordwood; a cord of maple sold for 37 and a half cents. The remaining portion of the population consisted of about 1,000 fishermen and their families. The fishing industry centered on Washington Island, which at 632 persons was the most populated area at the time. Sturgeon Bay had a population of 230 people. Fishermen caught lake trout and whitefish, which were sold for two cents per pound. Out of the total population of 2,948 people, 170 fought in the Civil War. Most enlisted in 1861 or 1862. The entire assessed valuation of the county that year was $395,000, with an average of $8.00 in tax assessed to each family. It was difficult to earn enough money to pay taxes, which were often delinquent. There were 25 school districts, but staffing was a challenge due to delinquent taxes. Highway 42 between Sturgeon Bay and Egg Harbor had 27 chronic mudholes, some more than 3,000 feet (910 m) long and passage by wagons was at times unfeasible.

When the 1871 Peshtigo fire burned the town of Williamsonville, fifty-nine people were killed. The area of this disaster is now Tornado Memorial County Park, named for a fire whirl which occurred there. Altogether, 128 people in the county perished in the Peshtigo fire. Following the fire, some residents decided to use brick instead of wood.

In 1883, Harry Dankoler at the Door County Advocate set a world typesetting record.

In 1885 or 1886, what is now the Coast Guard Station was established at Sturgeon Bay. The small, seasonally open station on Washington Island was established in 1902.

As the period of settlement continued, Native Americans lived in Door County as a minority. The 1890 census reported 22 Indians living in Door County. They were self-supporting, subject to taxation, and did not receive rations. By the 1910 census their numbers had declined to nine.

In 1894 the Ahnapee and Western Railway was extended to Sturgeon Bay, with the first train arriving on August 9. In 1969, a train ran north of Algoma into the county for the last time, although trains continued to operate farther south until 1986.

From 1865 through 1870, three resort hotels were constructed in and near Sturgeon Bay along with another one in Fish Creek. One resort established in 1870 charged $7.50 per week (around $160 in 2021 dollars). Although the price included three daily meals, extra was charged for renting horses, which were also available with buggies and buggy-drivers. Besides staying in hotels, tourists also boarded in private homes. Tourists could visit the northern part of the county by Great Lakes passenger steamer, sometimes as part of a lake cruise featuring music and entertainment. Reaching the peninsula from Chicago took three days. The air surrounding the agricultural communities was relatively free of ragweed pollen because grain crops matured slowly in the cool climate and were harvested late in the year. This prevented late-season ragweed infestations in the stubble, which was especially attractive to those with hay fever in the city.

Even after the Ahnapee and Western extended service to Sturgeon Bay in 1894, many tourists continued taking the railroad to Menominee, Michigan to embark on steamships bound for communities in Door County. This route over Green Bay bypassed poor road conditions in the northern part of the county, which persisted until the early 1920s. Only after crushed stone highways were built did motor and horse-drawn coaches become popular for transportation between Sturgeon Bay and the northern part of the peninsula. By 1909 at least 1,000 tourists visited per year, a figure which grew to about 125,000 in 1920, 1 million in 1969, 1.25 million in 1978, and 1.9 million in 1995. In 1938 Jens Jensen cautioned about negative cultural impacts of tourism. He wrote, “Door County is slowly being ruined by the stupid money crazed fools. This tourist business is destroying the little bit of culture that was.”

In 1865, the first commercial fruit operation was established when grapes were cultivated on one of the Strawberry Islands. By 1895, a large fruit tree nursery was established and fruit horticulture was aggressively promoted. Not only farmers but even “city-bred” men were urged to consider fruit husbandry as a career. The first of multiple fruit marketing cooperatives began in 1897. In addition to corporate-run orchards, in 1910 the first corporation was established to plant and sell pre-established orchards. Although apple orchards predated cherry orchards, by 1913 it was reported that cherries had outpaced apples.

Women and children were typically employed to pick fruit crops, but the available work outstripped the labor supply. By 1918, it was difficult to find enough help to pick fruit crops, so workers were brought in by the YMCA and Boy Scouts of America. Cherry picking was marketed as a good summer camp activity for teenage boys in return for room, board, and recreation activities. One orchard hired players from the Green Bay Packers as camp counselors. Additionally, members of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin and other native tribes were employed to pick fruit crops. In addition to their pay, Native American families were given fruit that was too ripe for marketing, which they preserved and stored for long term use. A Civilian Conservation Corps camp was established at Peninsula State Park during the Great Depression. In the summer of 1945, Fish Creek was the site of a POW camp under an affiliation with a base camp at Fort Sheridan, Illinois. The German prisoners engaged in construction projects, cut wood, and picked cherries in Peninsula State Park and the surrounding area. During a brief strike, the POWs refused to work. In response the guards established a “no work, no eat” policy and they returned to work, picking 11 pails per day and eventually totaling 508,020 pails.

The Wisconsin State Employment Service established an office in Door County in 1949 to recruit Tejanos to pick cherries. Work was unpredictable, as cherry harvests were poor during certain years and workers were paid by the amount they picked. In 1951, the Wisconsin Department of Public Welfare conducted a study documenting conflict between migrant workers and tourists, who resented the presence of migrant families in public vacation areas. A list of recommendations was prepared to improve race relations. The employment of migrants continues to the present day. In 2013, there were three migrant labor camps in the county, housing a total of 57 orchard laborers and food processors along with five non-workers.

In the fall of 1901, passenger pigeons were seen in Forestville, “in quite large flocks”. This is the last reported sighting in the county. Before the forests were cleared away, myriads of passenger pigeons nested in the woods of the Door Peninsula, and during periods of migration they would frequently and effectually cloud the sun in their flight.

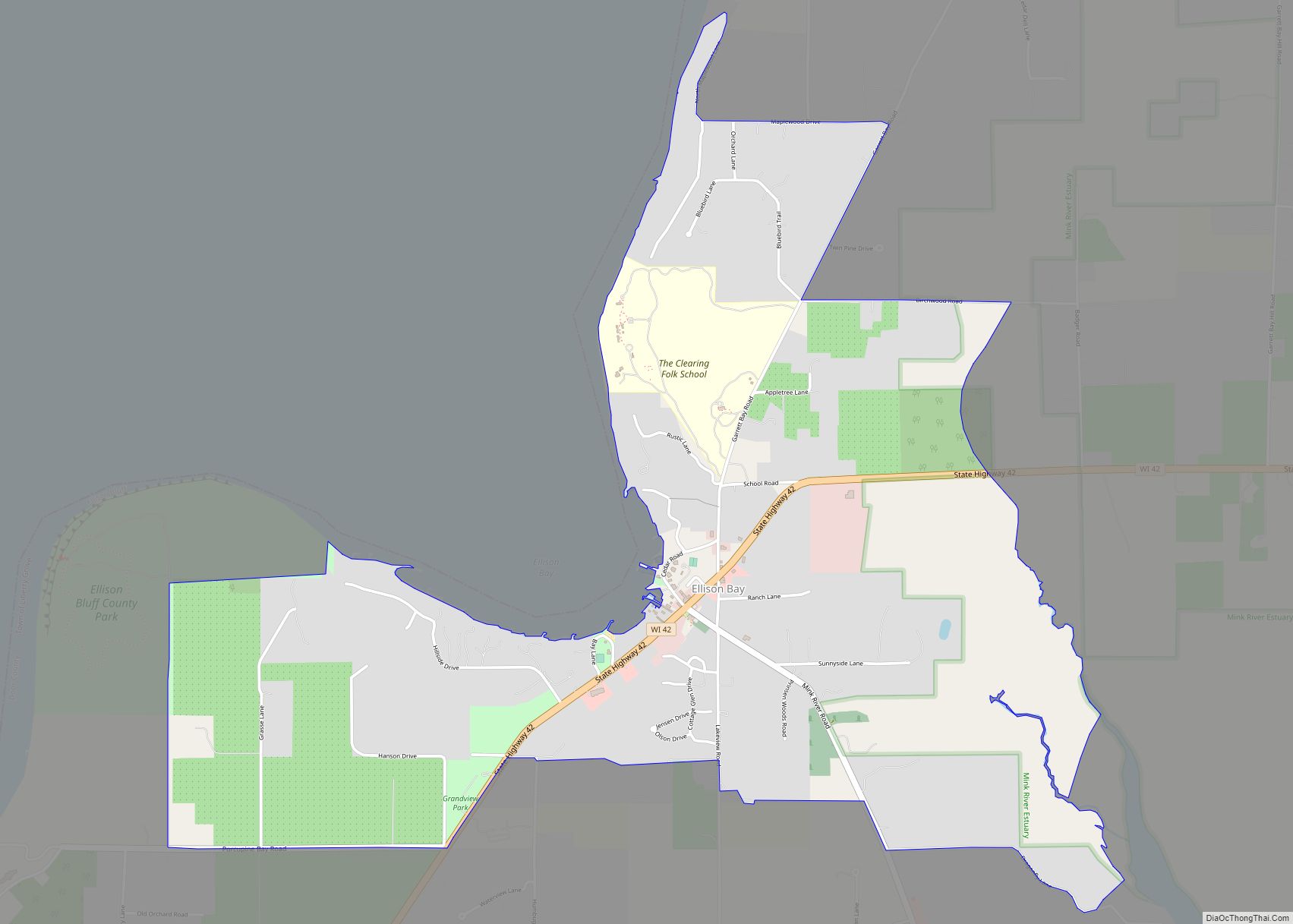

In 1905, the Lilly Amiot was in Ellison Bay with a load of freight, dynamite, and gasoline when it caught fire. After being cut loose, it drifted until exploding; the explosion was heard up to 15 miles away.

In 1912, the barnstormer Lincoln Beachey demonstrated his biplane during the county fair; this is believed to be the first takeoff and landing in the county.

In 1913, The Old Rugged Cross was first sung at the Friends Church in Sturgeon Bay as a duet by two traveling preachers.

In 1919, the first Army-Navy hydrogen balloon race was won by an Army team whose balloon splashed down in the Death’s Door passage. Two soldiers endured 10-foot (3 m) waves for an hour before their rescue by a fisherman.

In 1925, a cow in Horseshoe Bay named Aurora Homestead Badger produced 30,000 pounds (14,000 kg) of milk, at the time a world record for dairy cattle.

In June 1938 and again in October 1952, aerial photos were taken of the entire county; in 2011 the 1938 photos were made available online.

On June 14, 1939, Ted Bellak flew his the German-made glider Dove of Peace for 56 miles (90 km) from the newly opened Cherryland Airport to Frankfort, Michigan. He was towed into the air on a 3⁄8-inch-wide (9.5 mm), 200-foot-long (61 m) rope prior to gliding independently. At the time, this was the farthest distance traveled in a glider over a body of water. The trip took one hour and six minutes, with 57 minutes spent over Lake Michigan.

In 1941, the Sturgeon Bay Vocation School opened. It is now the Sturgeon Bay campus of Northeast Wisconsin Technical College.

In December 1959, the Bridgebuilder X disappeared after leaving a shipyard in Sturgeon Bay where it had been repaired. Its intended destinations were Northport and South Fox Island. Possible factors included lack of ballast and a sudden development of 11-foot (3.4 m) waves. The body of one of the two crew members was found the following summer.

In 2004, the county began a sister cities relationship with Jingdezhen in southeastern China.

To encourage tourism, Ephraim residents passed referendums in 2016 to allow beer and wine to be sold for consumption on premises within the village and to allow beer and single, recorked bottles of opened wine to be sold off-premises. Until then, Ephraim had been the state’s last dry municipality.

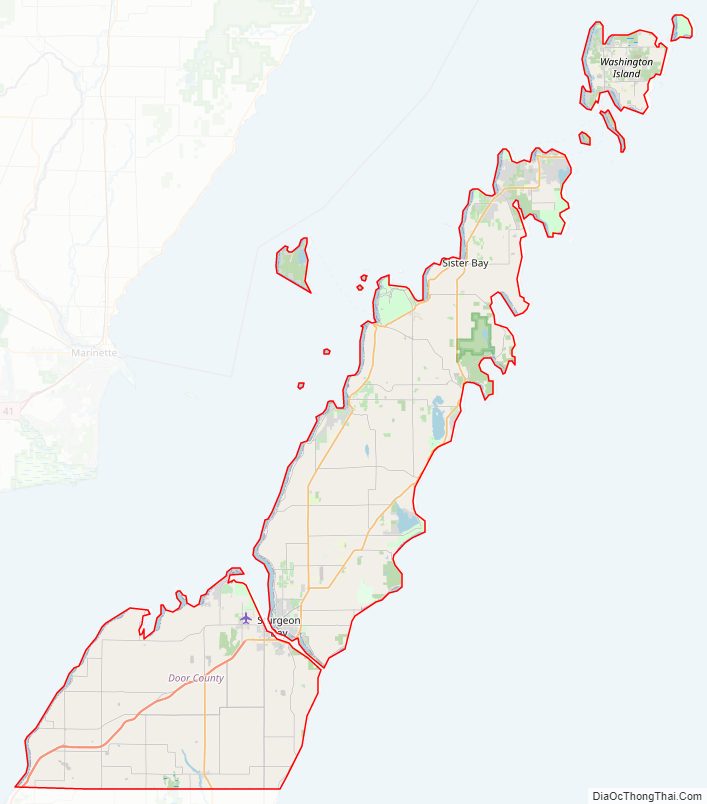

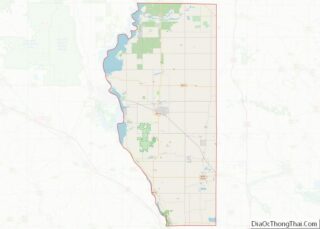

Door County Road Map

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 2,370 square miles (6,100 km), of which 482 square miles (1,250 km) is land and 1,888 square miles (4,890 km) (80%) is water. It is the largest county in Wisconsin by total area.

In general the shoreline is characterized by the scarp face on the west side. On the east side peat is followed by dunes and beaches of sand or gravel along the lakeshore. During years with receding lake levels, flora along the shore demonstrates plant succession. The middle of the peninsula is mostly flat with some rolling. There are three distinct aquifers and two types of springs present in the county.

The county covers the majority of the Door Peninsula. With the completion of the Sturgeon Bay Shipping Canal in 1881, the northern half of the peninsula became an artificial island. This canal is believed to have somehow “caused a wonderful increase in the quantity of fish” in nearby waters and also caused a reduction in the sturgeon population in the bay due to changes in the aquatic habitat. The 45th parallel north bisects the “island,” and this is commemorated by Meridian County Park.

Features

Dolomite outcroppings of the Niagara Escarpment are visible on both shores of the peninsula, but cliffs along the cuesta ridge are especially prominent on the Green Bay side, including at Bayshore Blufflands. South of Sturgeon Bay the steep side of the escarpment separates into multiple lower ridges without as many larger exposed rock faces. The face of the escarpment varies in appearance. It may consist of a bare rock face of dolomite alone, or as a face with dolomite above and shale underneath. Sometimes the rock layers are covered with glacial till.

Dolomites in the county have been separated by the different patterns marking the rocks. Each pattern is thought to represent a different general marine habitat from their formation. One layer has relatively straight and flat marks in the rocks, and is accompanied by fossils indicating a tidal flat, especially ostracods. The second layer of rocks has ripple marks and wavy patterns. Since the corals and shells in this layer are broken, the layer is inferred to have formed farther down along the reef shelf, where the corals and shells were exposed to the pounding of the waves. The third layer has rocks full of fossil burrows from marine animals. This layer formed in a still-deeper part of the middle reef under mostly calm conditions. Here, calm waters protected an abundant number of burrowing animals. Along with the fossil burrows are corals, brachiopods, and echinoderms. Yet the rocks in the third layer are interspersed with broken and disturbed material, indicating periodic storms. Each of these three layers is divided into smaller and more detailed sublayers.

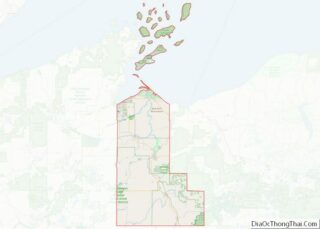

The bluffs are interrupted by a series of lowlands which stretch along a northwest to southeast direction; Sturgeon Bay and the Portes de Mortes passage are two of these lowlands. Beyond the peninsula’s northern tip, the partially submerged ridge forms the Potawatomi Islands, which stretch to the Garden Peninsula in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. The largest of these is Washington Island. The islands form the Town of Washington and also the southern part of Fairbanks Township in Delta County, Michigan. The lakebed along the scarp face on the Green Bay side has a sharp bottom gradient, while in many places the lakebed of the Lake Michigan side has a more gentle bottom gradient.

Areas overlooking the scarp face are attractive locations for houses and communications towers, and the stone of the escarpment is quarried. A former stone quarry five miles northeast of Sturgeon Bay is now a county park. Many caves are found in the escarpment.

The county has 298 miles (480 km) of shoreline. In 2012, 268 miles (431 km) of the shoreline along Lake Michigan and Green Bay was surveyed and characterized by type. 42.9 miles (69.0 km) of the shore was made of artificial materials, while the remaining 225.1 miles (362.3 km) was natural. Of the natural shorelines, 167.8 miles (270.0 km) consisted of bedrock and boulders, 39.3 miles (63.2 km) was sandy, 17.4 miles (28.0 km) were covered in smaller stones such as shingles, pebbles, and cobbles, and 0.6 miles (0.97 km) was silty or mucky. Out of the total area surveyed, 101.0 miles (162.5 km) consisted of a flat coast, 88.9 miles (143.1 km) consisted of 2-to-10-foot (1 to 3 m) bluffs, 68.8 miles (110.7 km) consisted of 2-to-10-foot (1 to 3 m) dunes, and 9.3 miles (15.0 km) consisted of high bluffs taller than 10 feet (3 m).

Eskers are only found in the far southwest corner of the county, but drumlins and small moraines also occur farther up the peninsula. The Door-Leelanau Ridge is an underwater moraine cutting across Lake Michigan between Door and Leelanau counties. A lacustrine terrace is located in Robert LaSalle Park.

The 102-foot-high (31 m) Brussels Hill (44°45′06″N 87°35′27″W / 44.75166°N 87.59093°W / 44.75166; -87.59093 (Brussels Hill), elevation 851 feet [259 m]) is the highest point in the county. The nearby Red Hill Woods is the largest remaining maple–beech forest in the area.

Old Baldy (44°55′13″N 87°12′07″W / 44.920344°N 87.20192°W / 44.920344; -87.20192 (Old Baldy)) is the state’s tallest sand dune at 93 feet above the lake level.

Pollution

The combination of shallow soils and fractured bedrock makes well water contamination more likely. At any given time, at least one-third of private wells may contain bacteria.

Mines, prior landfills, and former orchard sites are considered impaired lands and marked on an electronic county map. A different electronic map shows the locations of private wells polluted with lead, arsenic, and other contaminants down to the section level.

Most air pollution reaching the monitor in Newport State Park comes from outside the county. The stability of air over the Lake Michigan shore along with the lake breezes may increase the concentration of ozone along the shoreline. Additionally, pollution modeling predicts the presence of locally generated air pollution associated with vehicular traffic in the city of Sturgeon Bay.

Soils

The most common USDA soil association in the northern two-thirds of the county is the Summerville-Longrie-Omena. These associated soils typically are less than three feet deep. Altogether, thirty-nine percent of the county is mapped as having less than three feet (about a meter) to the dolomite bedrock. Because there is relatively little soil over much of the peninsula and the bedrock is fractured, snowmelt quickly enters the aquifer. This causes seasonal basement flooding in some areas.

Soils in the county are classified as “frigid” because they usually have an average annual temperature of less than 46.4 °F (8.0 °C). The implication of this classification is that county soils are expected to be wetter and have less microbial activity than soils in warmer areas classified as “mesic.” County soils are colder than those in inland areas of Wisconsin due to the climate-moderating effects of nearby bodies of water.

Climate

The county has a humid continental climate (classified as Dfb in Köppen) with warm summers and cold snowy winters. Data from the Peninsular Agricultural Research Station north of the city of Sturgeon Bay gives average monthly temperatures ranging from 68.7 °F (20.4 °C) in the summer down to 18.0 °F (−7.8 °C) in the winter. The moderating effects of nearby bodies of water reduce the likelihood of damaging late spring freezes. Late spring freezes are less likely to occur than in nearby areas, and when they do occur, they tend not to be as severe.