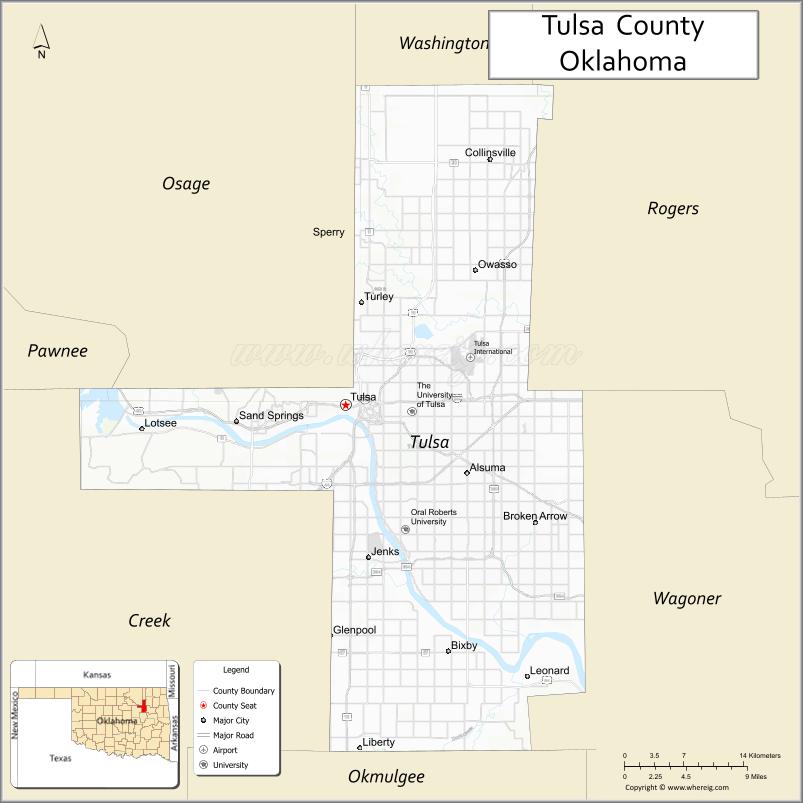

Tulsa County is located in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. As of the 2020 census, the population was 669,279, making it the second-most populous county in Oklahoma, behind only Oklahoma County. Its county seat and largest city is Tulsa, the second-largest city in the state. Founded at statehood, in 1907, it was named after the previously established city of Tulsa. Before statehood, the area was part of both the Creek Nation and the Cooweescoowee District of Cherokee Nation in Indian Territory.

Tulsa County is included in the Tulsa Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Tulsa County is notable for being the most densely populated county in the state. Tulsa County also ranks as having the highest income.

| Name: | Tulsa County |

|---|---|

| FIPS code: | 40-143 |

| State: | Oklahoma |

| Founded: | 1907 |

| Named for: | city of Tulsa |

| Seat: | Tulsa |

| Largest city: | Tulsa |

| Total Area: | 587 sq mi (1,520 km²) |

| Land Area: | 570 sq mi (1,500 km²) |

| Total Population: | 669,279 |

| Population Density: | 1,134/sq mi (438/km²) |

| Time zone: | UTC−6 (Central) |

| Summer Time Zone (DST): | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Website: | www.tulsacounty.org |

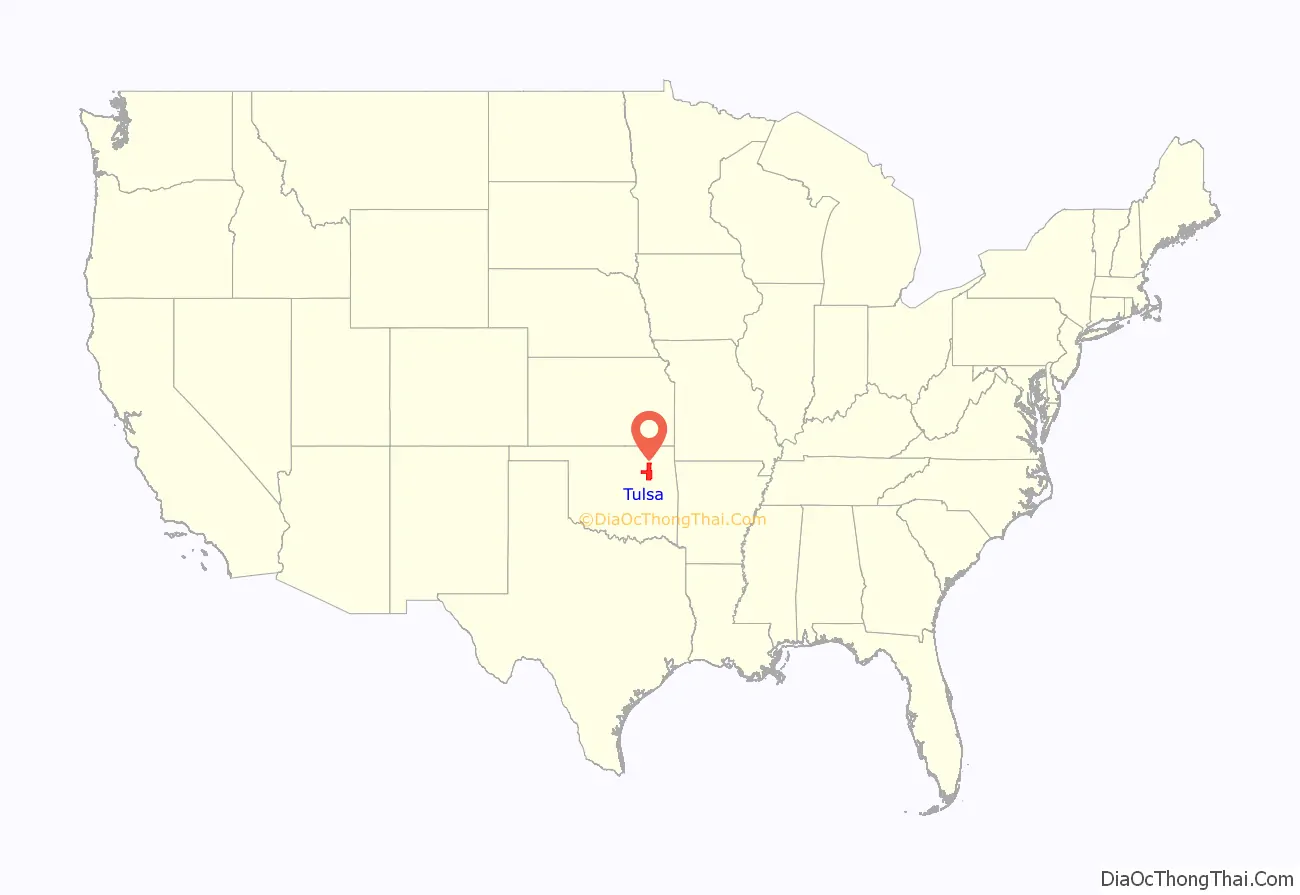

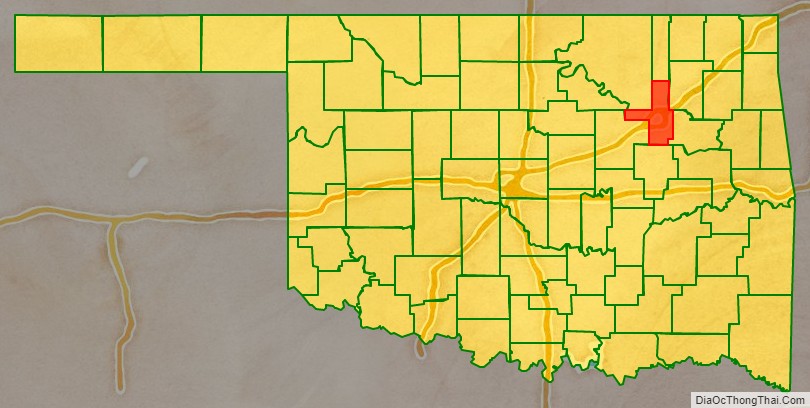

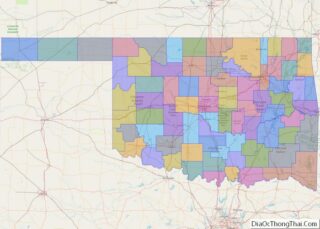

Tulsa County location map. Where is Tulsa County?

History

The history of Tulsa County greatly overlaps the history of the city of Tulsa. This section addresses events that largely occurred outside the present city limits of Tulsa.

Lasley Vore Site

The Lasley Vore Site, along the Arkansas River south of Tulsa, was claimed by University of Tulsa anthropologist George Odell to be the most likely place where Jean-Baptiste Bénard de la Harpe first encountered a group of Wichita people in 1719. Odell’s statement was based on finding both Wichita and French artifacts there during an architectural dig in 1988.

Old Fort Arbuckle

The U. S. Government’s removal of Native American tribes from the southeastern United States to “Indian Territory” did not take into account how that would impact the lives and attitudes of the nomadic tribes that already used the same land as their hunting grounds. At first, Creek immigrants stayed close to Fort Gibson, near the confluence of the Arkansas and Verdigris rivers. However, the government encouraged newer immigrants to move farther up the Arkansas. The Osage tribe had agreed to leave the land near the Verdigris, but had not moved far and soon threatened the new Creek settlements.

In 1831, a party led by Rev. Isaac McCoy and Lt. James L. Dawson blazed a trail up the north side of the Arkansas from Fort Gibson to its junction with the Cimarron River. In 1832, Dawson was sent again to select sites for military posts. One of his recommended sites was about two and a half miles downstream from the Cimarron River junction. The following year, Brevet Major George Birch and two companies of the 7th Infantry Regiment followed the “Dawson Road” to the aforementioned site. Flattering his former commanding officer, General Matthew Arbuckle, Birch named the site “Fort Arbuckle.”

According to Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, the fort was about 8 miles (13 km) west of the present city of Sand Springs, Oklahoma. Author James Gardner visited the site in the early 1930s. His article describing the visit includes an old map showing the fort located on the north bank of the Arkansas River near Sand Creek, just south of the line separating Tulsa County and Osage County. After ground was cleared and a blockhouse built, Fort Arbuckle was abandoned November 11, 1834. The remnants of stockade and some chimneys could still be seen nearly a hundred years later. The site was submerged when Keystone Lake was built.

Battle of Chusto-Talasah

Main article Battle of Chusto-Talasah

At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, many Creeks and Seminoles in Indian Territory, led by Opothleyahola, retained their allegiance to the U. S. Government. In November, 1861, Confederate Col. Douglas H. Cooper led a Confederate force against the Union supporters with the purpose of either compelling their submission or driving them out of the country. The first clash, known as the Battle of Round Mountain, occurred November 19, 1861. Although the Unionists successfully withstood the attack and mounted a counterattack, the Confederates claimed a strategic victory because the Unionists were forced to withdraw.

The next battle occurred December 9, 1861. Col. Cooper’s force attacked the Unionists at Chusto-Talasah (Caving Banks) on the Horseshoe Bend of Bird Creek in what is now Tulsa County. The Confederates drove the Unionists across Bird Creek, but could not pursue, because they were short of ammunition. Still, the Confederates could claim victory.

Coming of the railroads

The Atlantic and Pacific Railroad had extended its main line in Indian Territory from Vinita to Tulsa in 1883, where it stopped on the east side of the Arkansas River. The company, which later merged into the St. Louis and San Francisco Railway (familiarly known as the Frisco), then built a steel bridge across the river to extend the line to Red Fork. This bridge allowed cattlemen to load their animals onto the railroad west of the Arkansas instead of fording the river, as had been the practice previously. It also provided a safer and more convenient way to bring workers from Tulsa to the oil field after the 1901 discovery of oil in Red Fork.

Oil Boom

A wildcat well named Sue Bland No. 1 hit paydirt at 540 feet on June 25, 1901, as a gusher. The well was on the property of Sue A. Bland (née Davis), located near the community of Red Fork. Mrs. Bland was a Creek citizen and wife of Dr. John C. W. Bland, the first practicing physician in Tulsa. The property was Mrs. Bland’s homestead allotment. Oil produced by the well was shipped in barrels to the nearest refinery in Kansas, where it was sold for $1.00 a barrel.

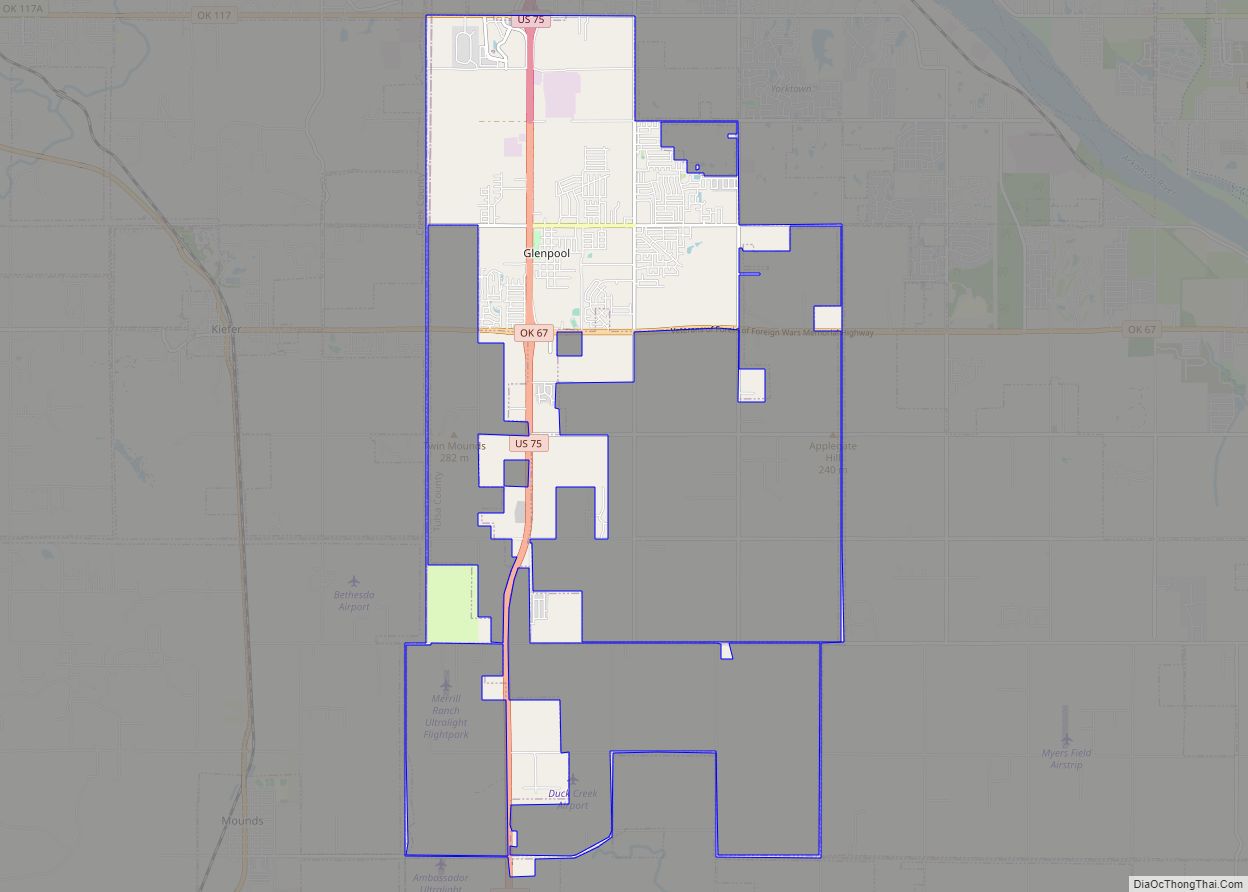

Other producing wells followed soon after. The next big strike in Tulsa County was the of Glenn Pool Oil Reserve in the vicinity of where Glenpool, Oklahoma was later founded..

Ironically, while the city of Tulsa claimed to be “Oil Capital of the World” for much of the 20th century, a city ordinance banned drilling for oil within the city limits.

Tulsa County Court House

In 1911–1912, Tulsa County built a court house in Tulsa on the northeast corner of Sixth Street and South Boulder Avenue. Yule marble was used in its construction. The land had previously been the site of a mansion owned by George Perryman and his wife. This was the court house where a mob of white residents gathered on May 31, 1921, threatening to lynch a young black man held in the top-floor jail. It was the beginning of the Tulsa Race Massacre.

An advertisement for bids specified that the building should be fireproof, built of either reinforced concrete or steel and concrete. The size was to be 120 feet (37 m) by 120 feet (37 m) with three floors and a full basement. Cost of the building was not to exceed $200,000. The jail on the top floor was not to exceed $25,000.

The building continued to serve until the present court house building (shown above) opened at 515 South Denver. The old building was then demolished and the land was sold to private investors. The land is now the site of the Bank of America building, completed in 1967.

1921 race riot

In the early 20th century, Tulsa was home to the “Black Wall Street”, one of the most prosperous Black communities in the United States at the time. Located in the Greenwood neighborhood, it was the site of the Tulsa Race Massacre, said to be “the single worst incident of racial violence in American history”, in which mobs of white Tulsans killed black Tulsans, looted and robbed the black community, and burned down homes and businesses. Sixteen hours of massacring on May 31 and June 1, 1921, ended only when National Guardsmen were brought in by the Governor. An official report later claimed that 23 Black and 16 white citizens were killed, but other estimates suggest as many as 300 people died, most of them Black. Over 800 people were admitted to local hospitals with injuries, and an estimated 1000 Black people were left homeless as 35 city blocks, composed of 1,256 residences, were destroyed by fire. Property damage was estimated at $1.8 million. Efforts to obtain reparations for survivors of the violence have been unsuccessful, but the events were re-examined by the city and state in the early 21st century, acknowledging the terrible actions that had taken place.

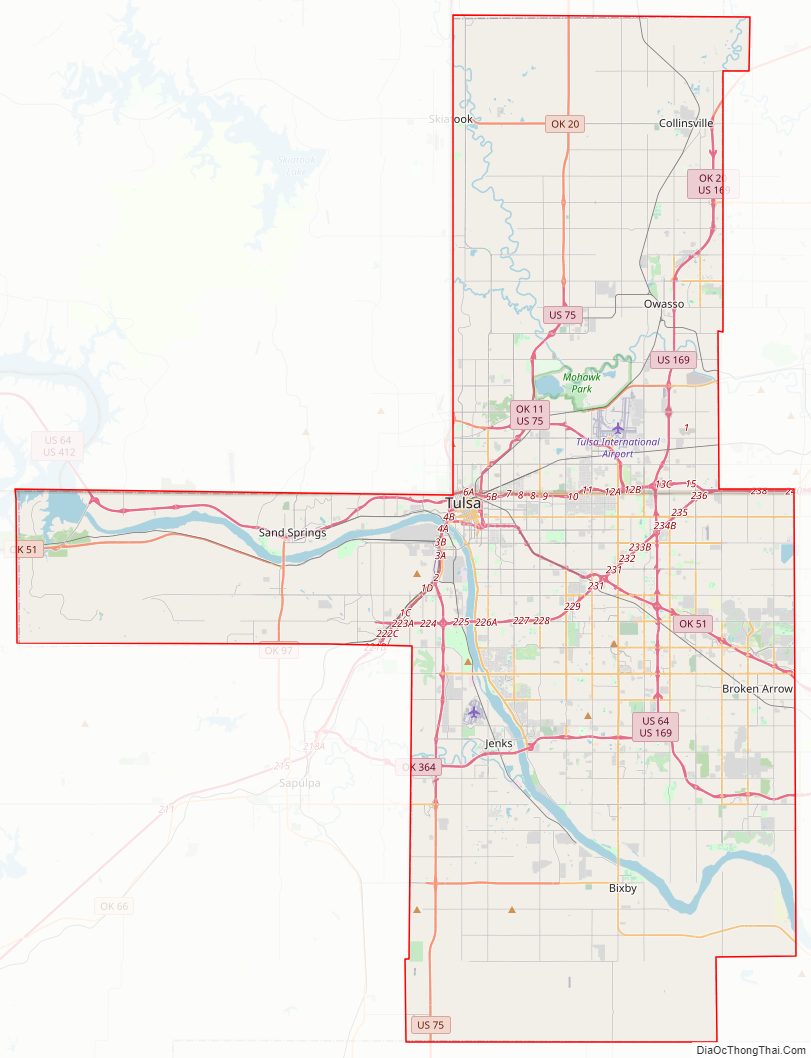

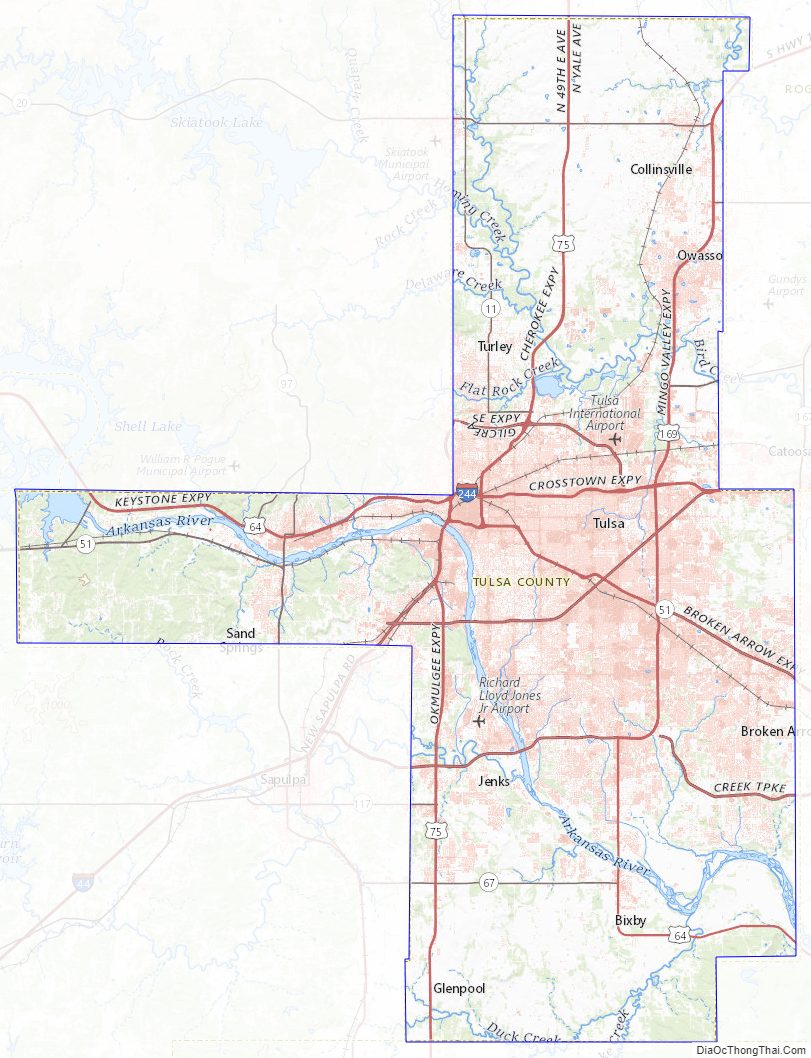

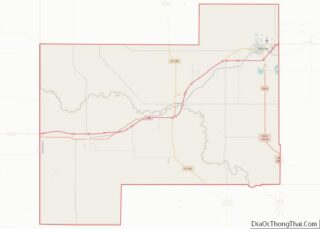

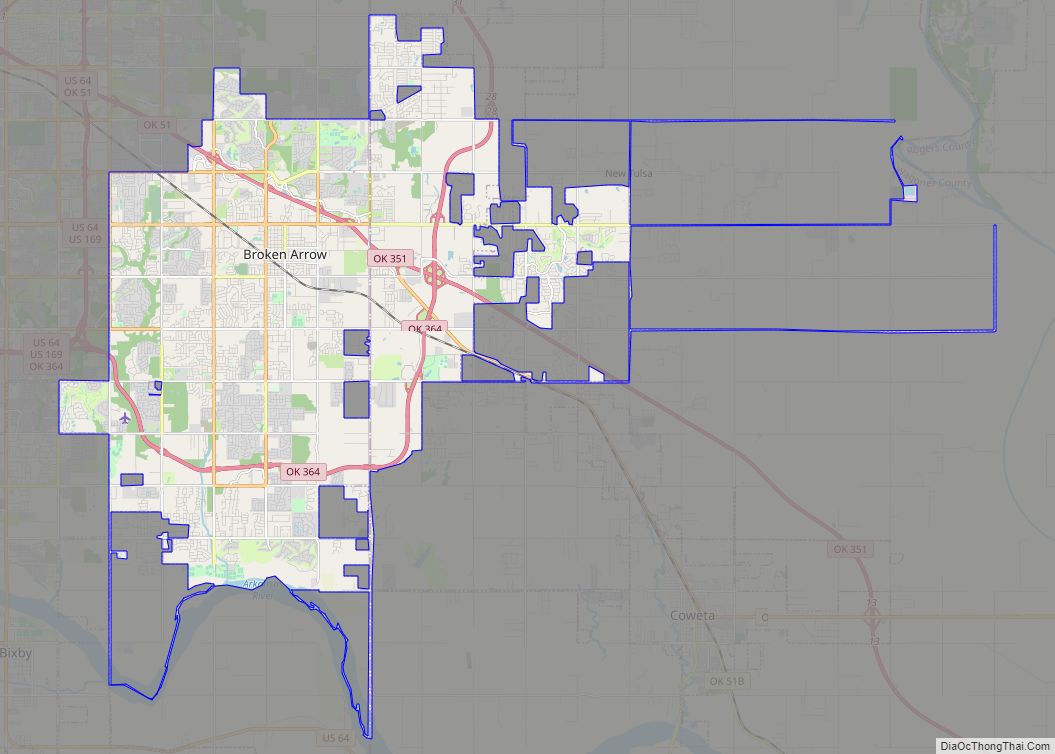

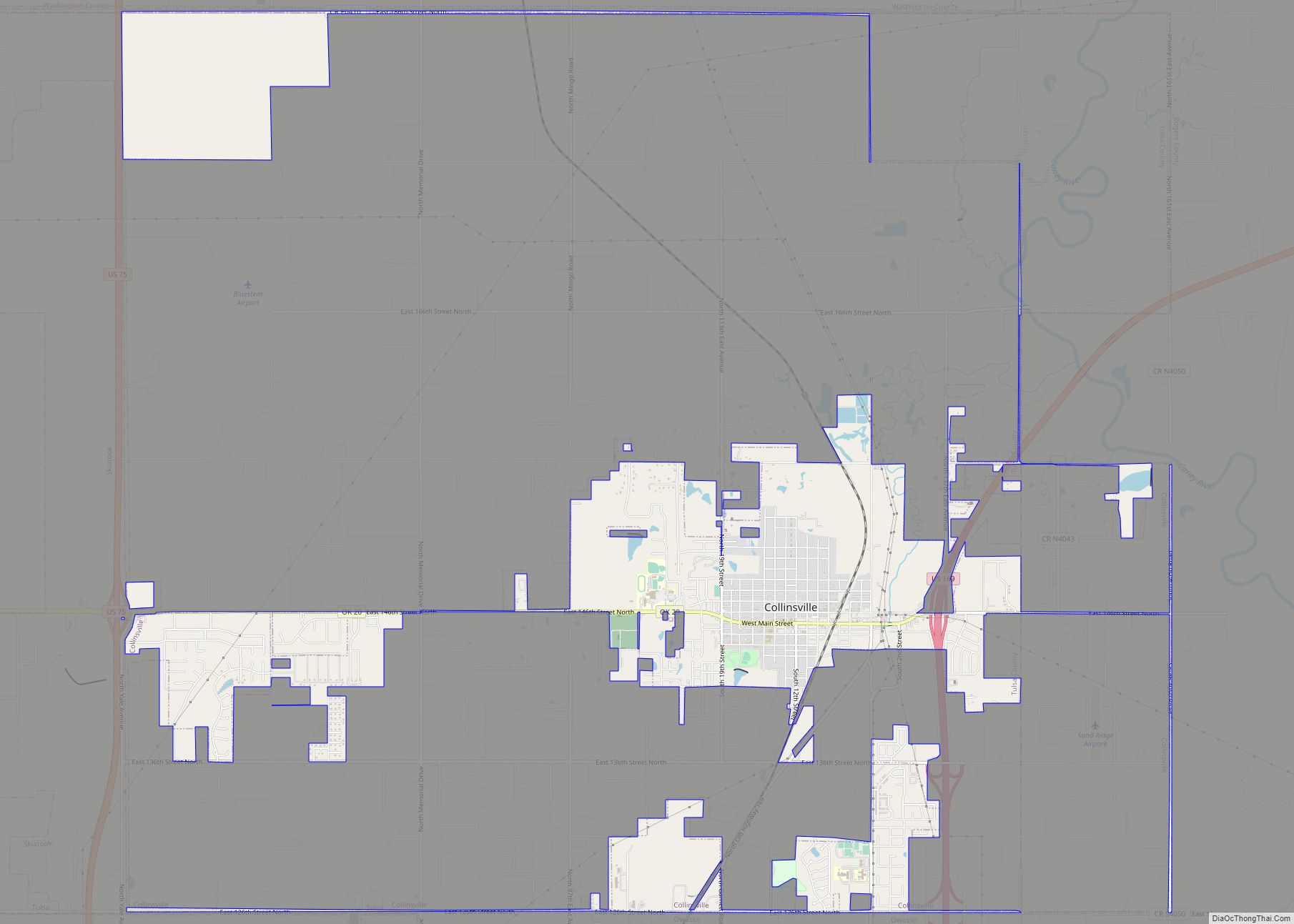

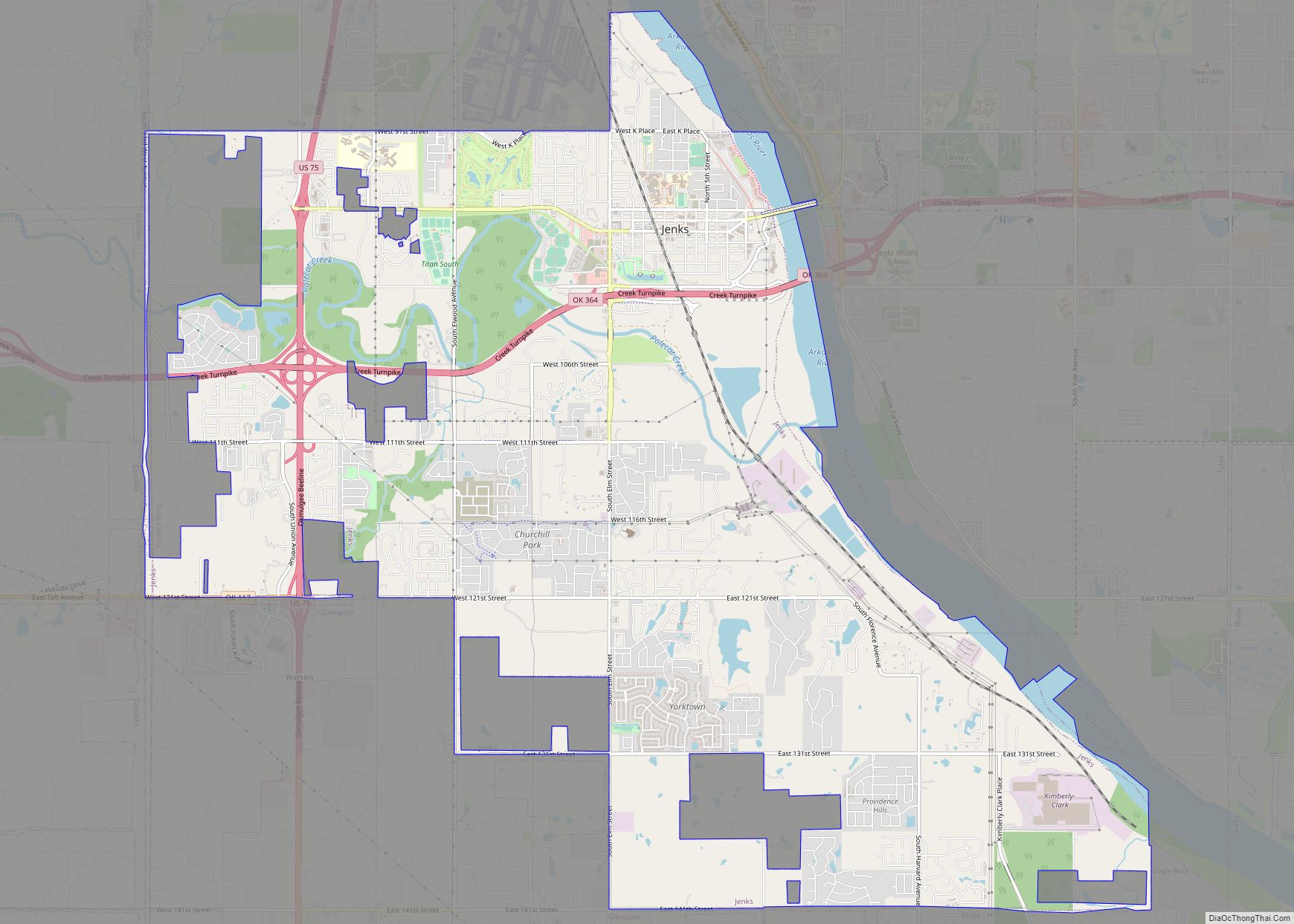

Tulsa County Road Map

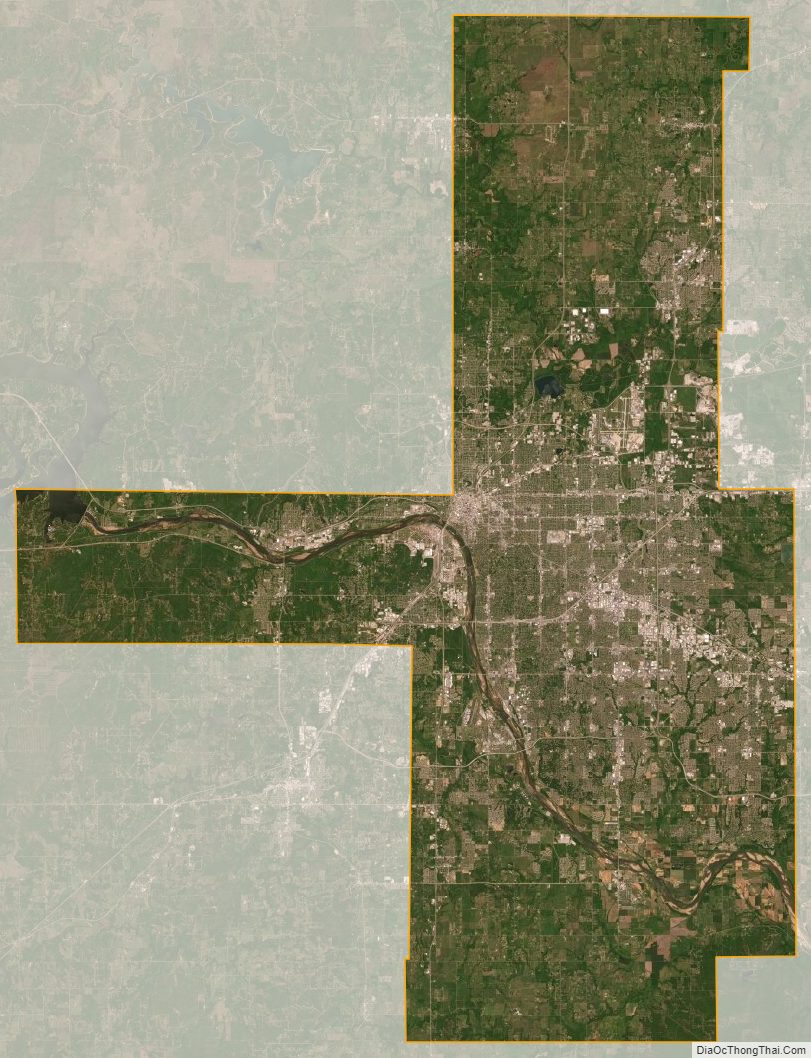

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 587 square miles (1,520 km), of which 570 square miles (1,500 km) is land and 17 square miles (44 km) (2.9%) is water.

The Arkansas River drains most of the county. Keystone Lake, formed by a dam on the Arkansas River, lies partially in the county. Bird Creek and the Caney River, tributaries of the Verdigris River drain the northern part of the county.

Adjacent counties

- Washington County (north)

- Rogers County (northeast)

- Wagoner County (southeast)

- Okmulgee County (south)

- Creek County (west)

- Pawnee County (northwest)

- Osage County (northwest)

Major highways

- Interstate 44

- Interstate 244

- Interstate 444

- U.S. Route 64

- U.S. Historic Route 66

- U.S. Route 75

- U.S. Route 169

- U.S. Route 412

- Creek Turnpike

- Oklahoma State Highway 11

- Former Oklahoma State Highway 12

- Oklahoma State Highway 20

- Oklahoma State Highway 51

- Oklahoma State Highway 67

- Oklahoma State Highway 97

- Oklahoma State Highway 97T

- Oklahoma State Highway 117

- Oklahoma State Highway 151

- Oklahoma State Highway 266

- Oklahoma State Highway 364

- Gilcrease Expressway

- L.L. Tisdale Parkway