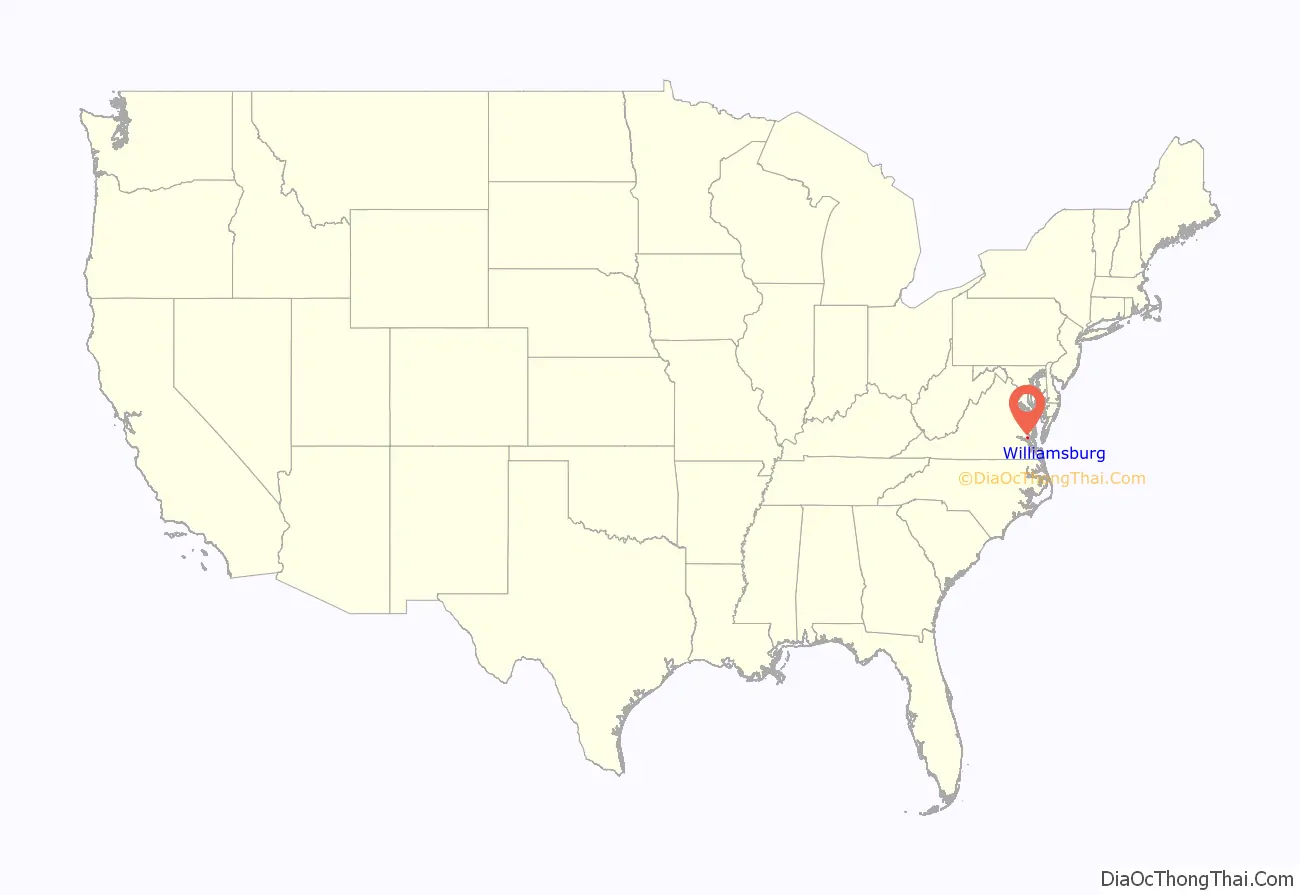

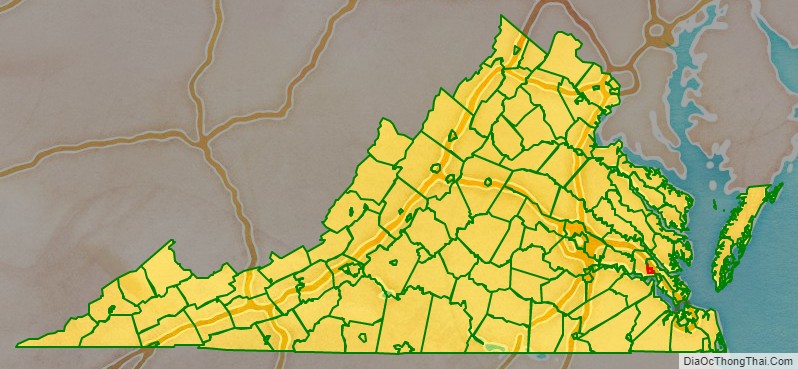

Williamsburg is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia, United States. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 15,425. Located on the Virginia Peninsula, Williamsburg is in the northern part of the Hampton Roads metropolitan area. It is bordered by James City County on the west and south and York County on the east.

English settlers founded Williamsburg in 1632 as Middle Plantation, a fortified settlement on high ground between the James and York rivers. The city functioned as the capital of the Colony and Commonwealth of Virginia from 1699 to 1780 and became the center of political events in Virginia leading to the American Revolution. The College of William & Mary, established in 1693, is the second-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and the only one of the nine colonial colleges in the South. Its alumni include three U.S. presidents as well as many other important figures in the nation’s early history.

The city’s tourism-based economy is driven by Colonial Williamsburg, the city’s restored Historic Area. Along with nearby Jamestown and Yorktown, Williamsburg forms part of the Historic Triangle, which annually attracts more than four million tourists. Modern Williamsburg is also a college town, inhabited in large part by William & Mary students, faculty and staff.

| Name: | Williamsburg City |

|---|---|

| FIPS code: | 51-830 |

| State: | Virginia |

| Founded: | 1632 |

| Total Area: | 9.10 sq mi (23.57 km²) |

| Land Area: | 8.94 sq mi (23.15 km²) |

| Total Population: | 15,425 |

| Population Density: | 1,700/sq mi (650/km²) |

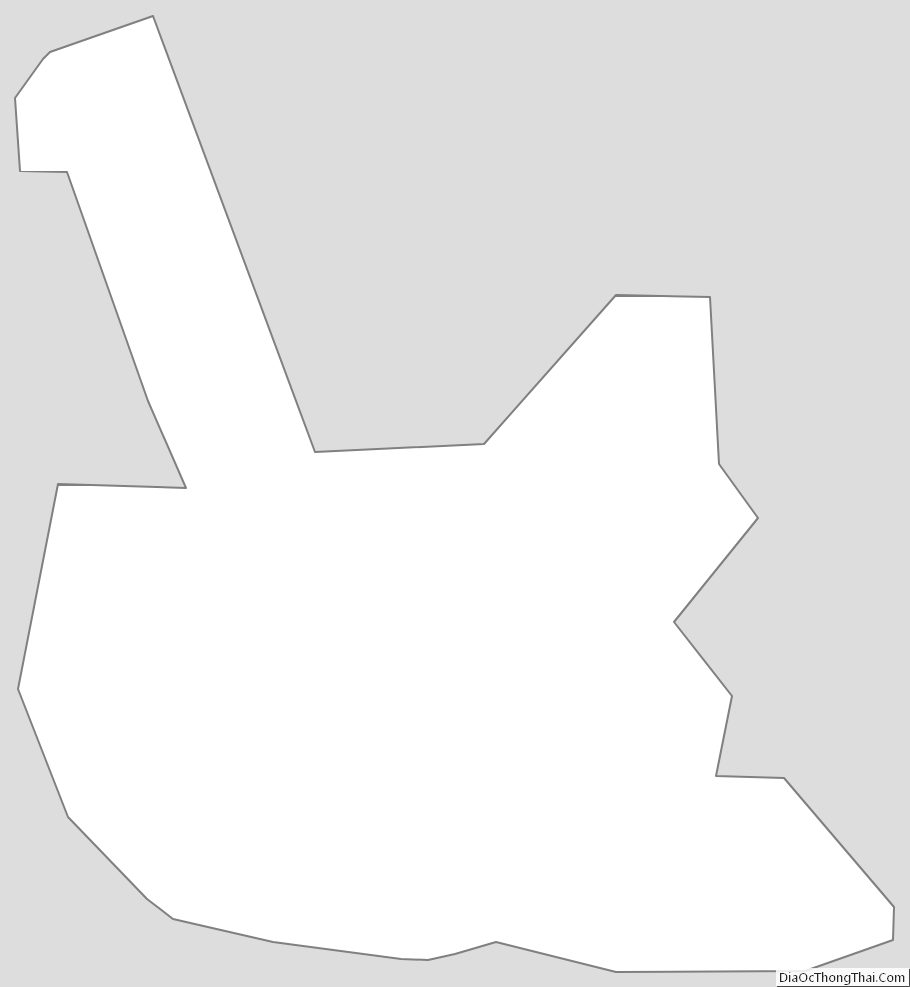

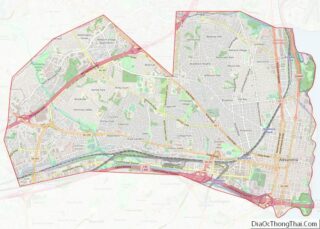

Williamsburg City location map. Where is Williamsburg City?

History

Origins

Before English settlers arrived at Jamestown to establish the Colony of Virginia in 1607, the area that would become Williamsburg formed part of the territory of the Powhatan Confederacy. By the 1630s, English settlements had grown to dominate the lower (eastern) portion of the Virginia Peninsula, and Powhatan tribes had abandoned their nearby villages. Between 1630 and 1633, after the war that followed the Indian Massacre of 1622, English colonists constructed a defensive palisade across the peninsula and a settlement named Middle Plantation as a primary guard-station along the palisade.

Jamestown, the original capital of Virginia Colony, burned down during the events of Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676. Once Governor William Berkeley had regained control, temporary government headquarters were established about 12 miles (19 km) away on the high ground at Middle Plantation, pending the rebuilding of the Statehouse at Jamestown. The members of the House of Burgesses discovered that the “temporary” location was both safer and more pleasant than Jamestown, which was humid and plagued with mosquitoes.

A school of higher education had long been an aspiration of the colonists. An early attempt at Henricus failed after the Indian Massacre of 1622; the location at the outskirts of the developed part of the colony had left it vulnerable to attack. In the 1690s, the colonists again tried to establish a school. They commissioned Reverend James Blair, who spent several years in England lobbying, and finally obtained a royal charter for the desired new school. It was to be named the College of William & Mary in honor of the monarchs of the time. When Blair returned to Virginia, the new school was founded in a safe place, Middle Plantation, in 1693. Classes began in temporary quarters in 1694, and construction soon started on the College Building, a precursor to the Wren Building.

Williamsburg as capital

Four years later, in 1698, the rebuilt Statehouse in Jamestown burned down again, this time accidentally. The government again “temporarily” relocated to Middle Plantation, and in addition to the better climate now also enjoyed use of the college’s facilities. The college students made a presentation to the House of Burgesses, and it was agreed in 1699 that the colonial capital would move to Middle Plantation permanently. A village was laid out and Middle Plantation was renamed Williamsburg in honor of King William III of England, befitting the town’s newly elevated status.

After Williamsburg’s designation as the colony’s capital, immediate provision was made for construction of a capitol building and for platting the city according to Theodorick Bland’s survey. His design utilized the college’s extant sites and the almost new Bruton Parish Church as focal points, and placed the new Capitol building opposite the college, with Duke of Gloucester Street connecting them.

Alexander Spotswood, who arrived in Virginia as lieutenant governor in 1710, had several ravines filled and streets leveled, and assisted in erecting additional college buildings, a church, and a magazine for the storage of arms. In 1722, Williamsburg was granted a royal charter as a “city incorporate” (now believed to be the oldest charter in the United States). It was actually a borough.

Middle Plantation was included in James City Shire when it was established in 1634, as the colony reached a total population of approximately 5,000. (James City and Virginia’s other shires changed their names a few years later; James City Shire then became known as James City County). The middle ground ridge-line was essentially the dividing line with Charles River Shire, which was renamed York County after King Charles I (r. 1625–1649) fell out of favor with the citizens of England. As Middle Plantation (and later Williamsburg) developed, the boundaries were adjusted slightly. For most of the colonial period, the border between the two counties ran down the center of Duke of Gloucester Street. During this time, and for almost 100 years after the 1776 formation both of the Commonwealth of Virginia and of the United States, despite practical complications, the town remained divided between the two counties.

Williamsburg was the site of the first attempted canal in the United States. In 1771, Lord Dunmore, who was Virginia’s last Royal Governor, announced plans to connect Archer’s Creek, which leads to the James River, with Queen’s Creek, leading to the York River. It would have formed a water route across the Virginia Peninsula, but was not completed. Remains of this canal are visible at the rear of the grounds behind the Governor’s Palace in Colonial Williamsburg.

In the 1770s, the first purpose-built psychiatric hospital in the United States, the Public Hospital for Persons of Insane and Disordered Minds, was founded in the city. Known in modern times as Eastern State Hospital, it was established by Act of the Virginia colonial legislature on June 4, 1770. The Act to “Make Provision for the Support and Maintenance of Ideots, Lunaticks, and other Persons of unsound Minds” authorized the House of Burgesses to appoint a 15-man Court Of Directors to oversee the hospital’s operations and admissions. In 1771, contractor Benjamin Powell constructed a two-story building on Francis Street near the college, capable of housing 24 patients. The design included “yards for patients to walk and take the Air in” as well as provisions for a fence to keep the patients out of the town.

The Gunpowder Incident began in April 1775 as a dispute between Dunmore and Virginia colonists over gunpowder stored in the Williamsburg magazine. Fearing rebellion, Dunmore ordered royal marines to seize gunpowder from the magazine. Virginia militia led by Patrick Henry responded to the “theft” and marched on Williamsburg. A standoff ensued, with Dunmore threatening to destroy the city if attacked by the militia. The dispute was resolved when payment for the powder was arranged. This was an important precursor in the run-up to the American Revolution. Following the Declaration of Independence from Britain, the American Revolutionary War broke out in 1776.

On July 25, 1776, the Declaration of Independence was proclaimed at Williamsburg and received with “applause under discharge of cannon and firing of small arms with illuminations [fireworks] in the evening”.

During the war, Virginia’s capital was moved again, in 1780, this time to Richmond at the urging of then-Governor Thomas Jefferson, who feared Williamsburg’s location made it vulnerable to a British attack. Williamsburg remained a venue for many important conventions during the war.

Decline and Civil War

Williamsburg ceased to be the capital of the new Commonwealth of Virginia in 1780 and went into decline, although not to the degree Jamestown had. Another factor was travel: 18th- and early 19th-century transportation in the colony was largely by canals and navigable rivers. As it had been built on “high ground”, Williamsburg was not sited on a major water-route, unlike many early U.S. communities. The railroads that began to be built in the 1830s also did not yet come through the city.

Despite Williamsburg’s loss of the business activity involved in government, the College of William and Mary continued and expanded, as did the Public Hospital for Persons of Insane and Disordered Minds. The latter became known as Eastern State Hospital.

At the outset of the American Civil War (1861–1865), enlistments in the Confederate Army depleted the College of William and Mary’s student body and on May 10, 1861, the faculty voted to close the college for the duration of the war. The College Building served as a Confederate barracks and later as a hospital before being burned by Union forces in 1862.

The Williamsburg area saw combat in the spring of 1862 during the Peninsula Campaign, a Union effort to take Richmond from the east from a base at Fort Monroe. Throughout late 1861 and early 1862, the small contingent of Confederate defenders was known as the Army of the Peninsula, led by General John B. Magruder. He successfully created ruses to fool the invaders as to the size and strength of his forces, and deterred their attack. The subsequent slow Union movement up the peninsula gained valuable time for defenses to be constructed at the Confederate capital at Richmond.

In early May 1862, after holding off Union troops for over a month, the defenders withdrew quietly from the Warwick Line (stretching across the Peninsula between Yorktown and Mulberry Island). As General George McClellan’s Union forces crept up the Peninsula to pursue the retreating Confederate forces, a rear-guard force led by General James Longstreet and supported by General J. E. B. Stuart’s cavalry blocked their westward progression at the Williamsburg Line. This was a series of 14 redoubts east of town, with earthen Fort Magruder (also known as Redoubt # 6) at the crucial junction of the two major roads leading to Williamsburg from the east. College of William and Mary President Benjamin S. Ewell oversaw the design and construction. He owned a farm in James City County, and had been commissioned as an officer in the Confederate Army after the college closed in 1861.

At the Battle of Williamsburg on May 5, 1862, the defenders succeeded in delaying the Union forces long enough for the retreating Confederates to reach the outer defenses of Richmond.

A siege of Richmond ensued, culminating in the Seven Days Battles (June to July 1862). McClellan’s campaign failed to capture Richmond. Meanwhile, on May 6, 1862, Williamsburg had fallen to the Union. The college’s Brafferton building operated for a time as quarters for the commanding officer of the Union garrison occupying the town. On September 9, drunken soldiers of the 5th Pennsylvania Cavalry set fire to the College Building, allegedly to prevent Confederate snipers from using it for cover. Williamsburg underwent much damage during the Union occupation, which lasted until September 1865.

Late 19th century

In 1881, Collis P. Huntington’s Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad (C&O) built its Peninsula Extension through the area, eventually establishing six stations in Williamsburg and the surrounding area. The Peninsula Extension was good news for the farmers and merchants of the Virginia Peninsula, and they generally welcomed the railroad, which aided passenger travel and shipping. Williamsburg allowed tracks to be placed down Duke of Gloucester Street and even directly through the ruins of the capitol building. (They were later relocated, and Collis Huntington’s real-estate arm, Old Dominion Land Company, donated the site to the forerunner of the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities.)

The railroad’s main purpose was shipping eastbound West Virginia bituminous coal to Newport News. Using the new coal piers, coal was loaded aboard large colliers in the harbor of Hampton Roads for shipment to New England and to export destinations worldwide.

Due in no small part to President Ewell’s efforts, education continued at the College of William and Mary, although teaching was temporarily suspended for financial reasons from 1882 to 1888. Ewell’s efforts to restore the school and its programs during and after Reconstruction became legendary in Williamsburg and at the college, and were ultimately successful, with funding both from the U.S. Congress and from the Commonwealth of Virginia. In 1888, the college secured $10,000 from the General Assembly of the Commonwealth and established a normal school to educate teachers; in 1906, the General Assembly modified the college charter, took ownership of the college buildings and grounds, and assumed primary responsibility for funding it. Ewell remained in Williamsburg as President Emeritus of the college until his death in 1894.

Beginning in the 1890s, C&O land agent Carl M. Bergh, a Norwegian-American who had earlier farmed in the midwestern states, realized that eastern Virginia’s gentler climate and depressed post-Civil War land prices would be attractive to his fellow Scandinavians who were farming in other northern parts of the country. He began sending out notices and selling land. Soon there was a substantial concentration of relocated Americans of Norwegian, Swedish, and Danish descent in the area. The location earlier known as Vaiden’s Siding on the railroad just west of Williamsburg in James City County was renamed Norge. These citizens and their descendants found the local conditions favorable, and many became leading merchants, tradespersons, and farmers in the community. These transplanted Americans brought some new blood and enthusiasm to the old colonial capital area.

Revival

Williamsburg remained a sleepy small town in the early 20th century. Some newer structures were interspersed with colonial-era buildings, but the town was much less progressive than Virginia’s other, busier communities of similar size. Some local lore indicates that the residents liked it that way, as described in longtime Virginia Peninsula journalist, author and historian Parke S. Rouse Jr.’s work. On June 26, 1912, the Richmond Times-Dispatch newspaper ran an editorial that dubbed the town “Lotusburg”, for “Tuesday was election day in Williamsburg but nobody remembered it. The clerk forgot to wake the electoral board, the electoral board could not arouse itself long enough to have the ballots printed, the candidates forgot they were running, the voters forgot they were alive.”

But even if such complacency existed, one Episcopal priest dreamed of expanding and changing Williamsburg’s future to give it a new major purpose, turning much of it into a massive living museum. In the early 20th century, the Reverend Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin of Williamsburg’s Bruton Parish Church championed one of the nation’s largest historic restorations. Initially, Goodwin just aimed to save his historic church building. This he had accomplished by 1907, in time for the 300th anniversary of the founding of the Episcopal Church in Virginia. But upon returning to Williamsburg in 1923 after serving a number of years in upstate New York, he realized that many of the other remaining colonial-era buildings were also in deteriorating condition.

Goodwin dreamed of a much larger restoration along the lines of what he had accomplished with his church. Of modest means, he sought support and financing from a number of sources before successfully attracting the interest and major financial support of Standard Oil heir and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr. and his wife Abby Aldrich Rockefeller. Their combined efforts created Colonial Williamsburg, restoring much of downtown Williamsburg and developing a 301-acre (1.22 km) Historic Area celebrating the patriots and early history of America.

As of 2022, Colonial Williamsburg is Virginia’s largest tourist attraction by attendance and the cornerstone of the Historic Triangle, with Jamestown and Yorktown joined by the Colonial Parkway. In the 21st century, Williamsburg has continued to update and refine its attractions. There are more features designed to attract modern children and to offer better and additional interpretation of the African-American experience in the town. A century after Goodwin’s work began, Colonial Williamsburg remains a work in progress.

In addition to Colonial Williamsburg, the city’s railroad station was restored to become an intermodal passenger facility. In nearby James City County, the c. 1908 C&O Railway combination passenger and freight station at Norge was preserved and, with a donation from CSX Transportation, relocated in 2006 to a site at the Williamsburg Regional Library’s Croaker Branch. Other landmarks outside the historic area include Carter’s Grove and Gunston Hall.

In 1932, a Catholic church was built to minister to students at the College of William & Mary. Old Saint Bede was made a national shrine, dedicated to Our Lady of Walsingham.

Recent history

The third of three debates between Republican President Gerald Ford and Democratic challenger Jimmy Carter was held at Phi Beta Kappa Memorial Hall at The College of William & Mary on October 22, 1976. Perhaps in tribute to the historic venue, as well as to the United States Bicentennial celebration, both candidates spoke of a “new spirit” in America.

The 9th G7 summit took place in Williamsburg in 1983. The participants discussed the growing debt-crisis, arms control and greater cooperation between the Soviet Union and the G7 (subsequently the G8). At the end of the meeting, Secretary of State George P. Shultz read to the press a statement confirming the deployment of American Pershing II-nuclear rockets in West Germany later in 1983.

On May 3, 2007, Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II visited Jamestown and Williamsburg. She had previously visited Williamsburg in 1957. Many world leaders, including President George W. Bush, visited Jamestown to mark its 400th anniversary. The celebration began in part in 2005 with events leading up to the anniversary, and was celebrated statewide throughout 2007, though the official festivities took place during the first week of May.

On February 5, 2009, President Barack Obama took his first trip aboard Air Force One to a House Democrats retreat in the city to attend and address their “Issues Conference”.

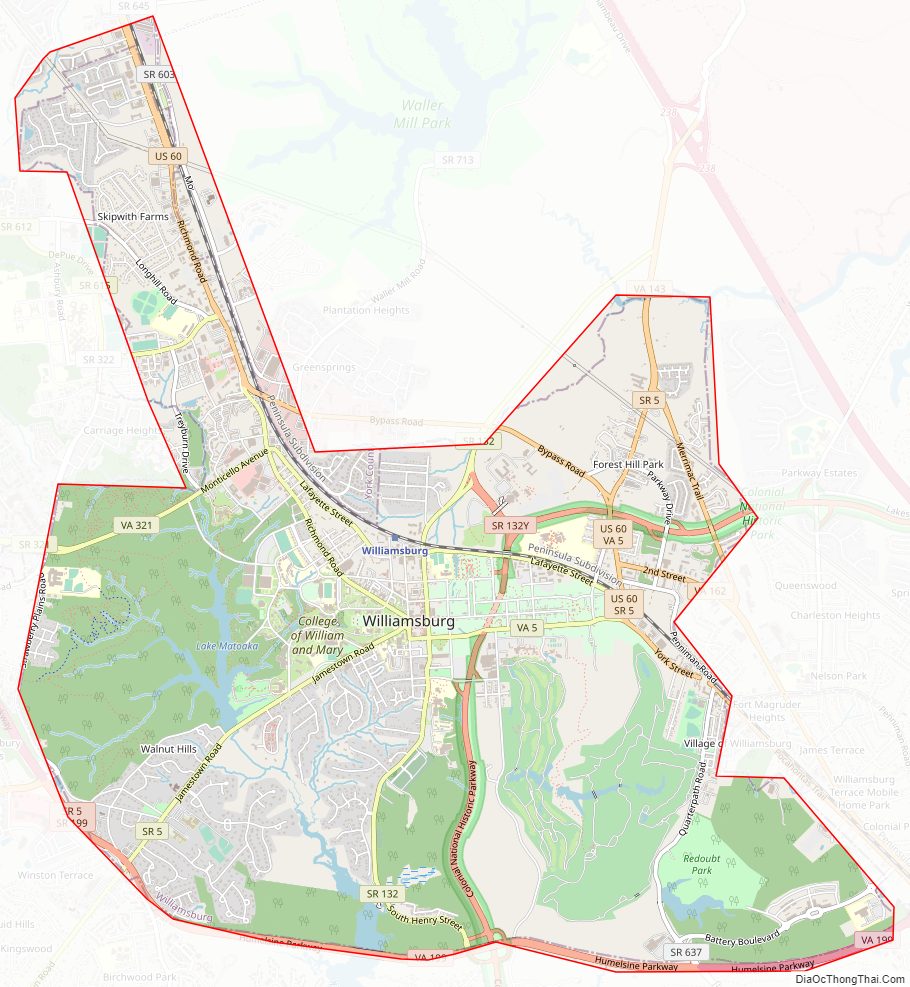

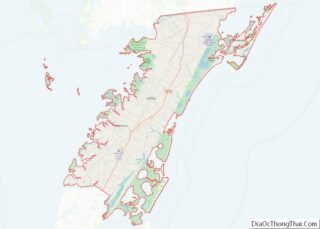

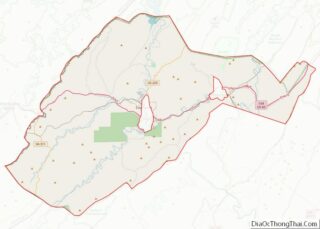

Williamsburg City Road Map

Geography

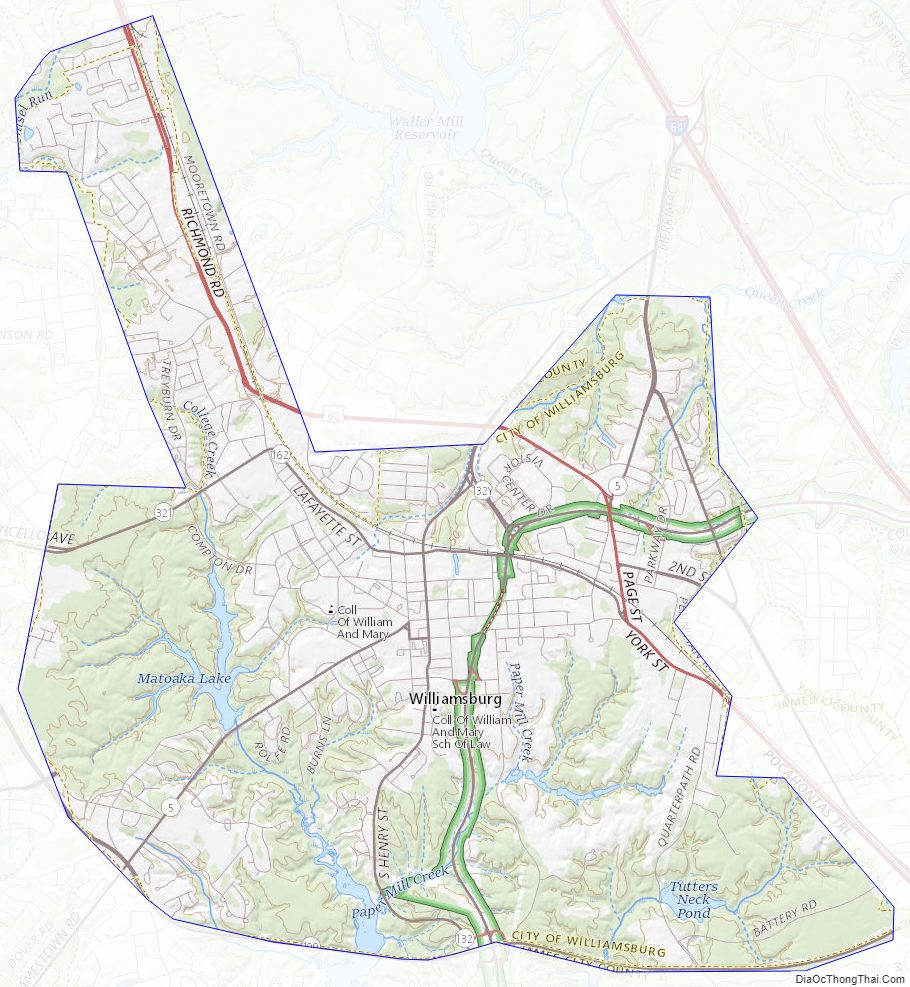

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 9.1 square miles (23.6 km), of which 8.9 square miles (23.1 km) is land and 0.2 square miles (0.5 km) (1.8%) is water.

Williamsburg stands upon a ridge on the Virginia Peninsula between the James and York Rivers. Queen’s Creek and College Creek partly encircle the city. James City County is to the west and south and York County to the north and east. As with all cities in Virginia, Williamsburg is legally independent of both counties.

The city is on the I-64 corridor, 45 miles (72 km) southeast of Richmond and about 37 miles (60 km) northwest of Norfolk. It is in the northwest corner of Hampton Roads, the nation’s 37th-largest metropolitan area, with a population of 1,576,370. Within Hampton Roads, Norfolk is recognized as the central business district, while the Virginia Beach seaside resort district and Williamsburg are primarily tourism centers.

Climate

Williamsburg is in the humid subtropical climate zone, with cool to mild winters, and hot, humid summers. Due to the inland location, winters are slightly cooler and spring days slightly warmer than in Norfolk, though lows average 3.2 °F (1.8 °C) cooler here due to the substantial urban buildup to the southeast. Snowfall averages 4.3 inches (11 cm) per season, and the summer months tend to be slightly wetter. With a period of record dating only back to 1951, extreme temperatures range from −7 °F (−22 °C) on January 21, 1985, to 104 °F (40 °C) on August 22, 1983, and June 26, 1952.