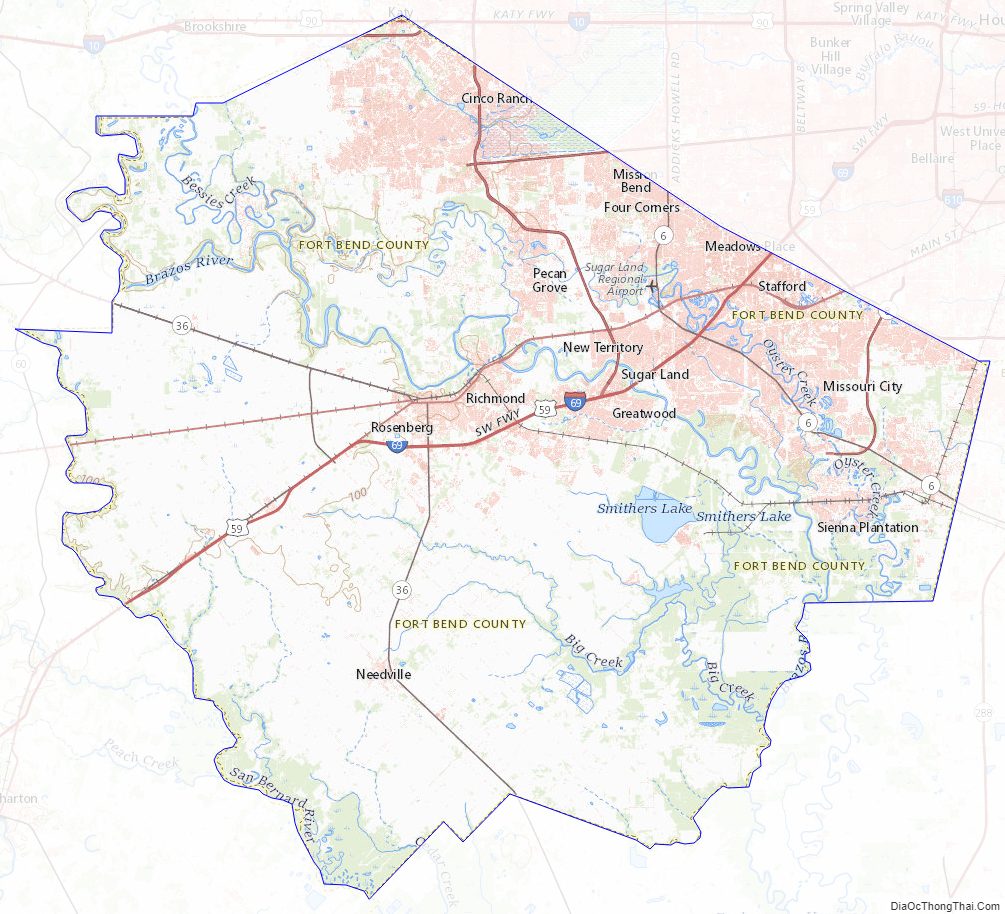

| Name: | Fort Bend County |

|---|---|

| FIPS code: | 48-157 |

| State: | Texas |

| Founded: | 1838 |

| Named for: | A blockhouse positioned in a bend of the Brazos River |

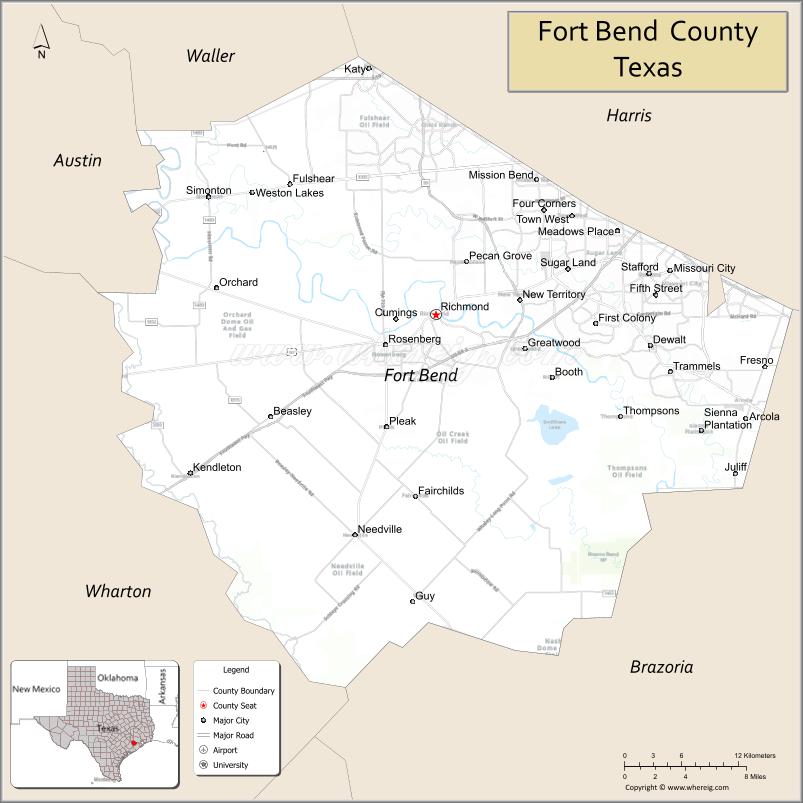

| Seat: | Richmond |

| Largest city: | Sugar Land |

| Total Area: | 885 sq mi (2,290 km²) |

| Land Area: | 861 sq mi (2,230 km²) |

| Total Population: | 822,779 |

| Population Density: | 930/sq mi (360/km²) |

| Time zone: | UTC−6 (Central) |

| Summer Time Zone (DST): | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Website: | www.fortbendcountytx.gov |

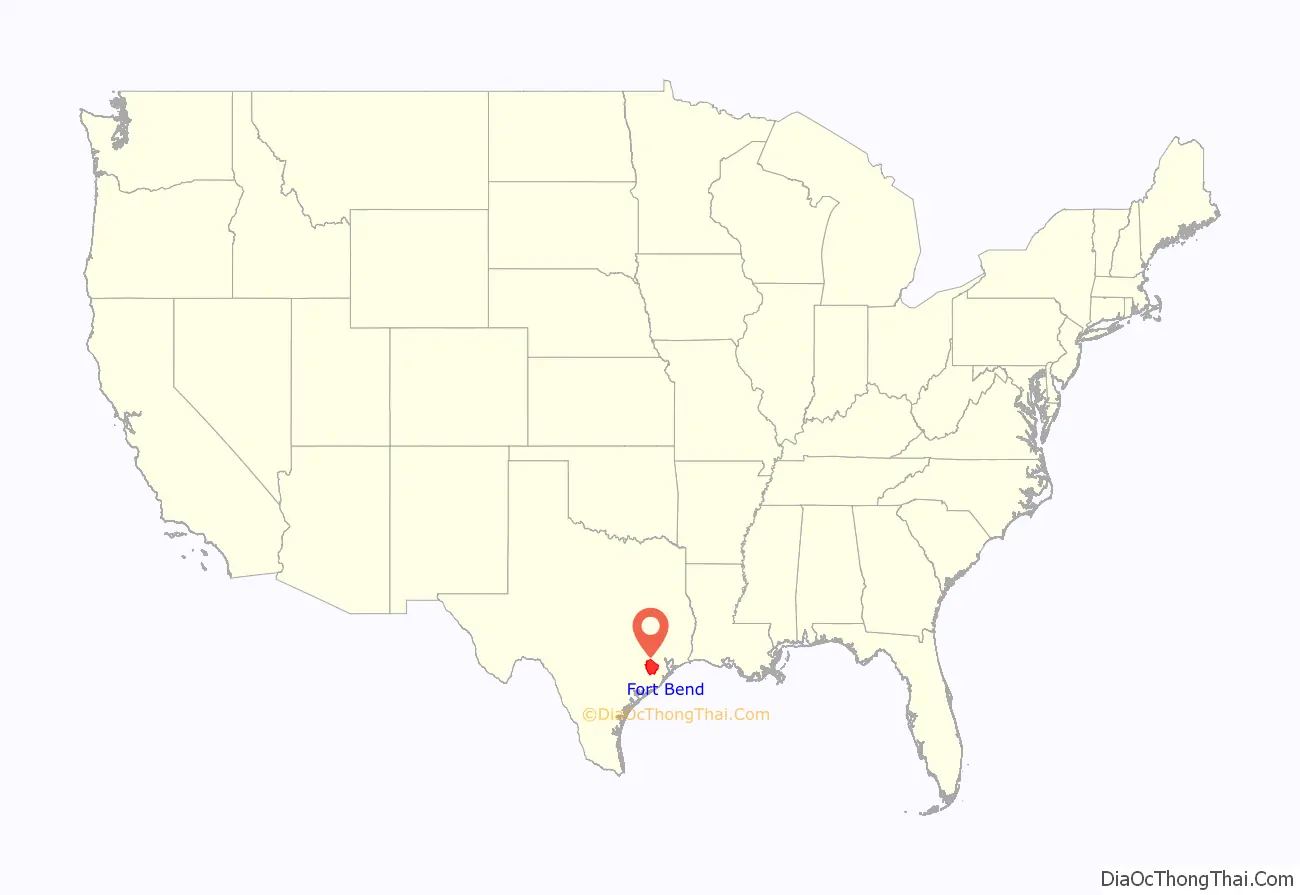

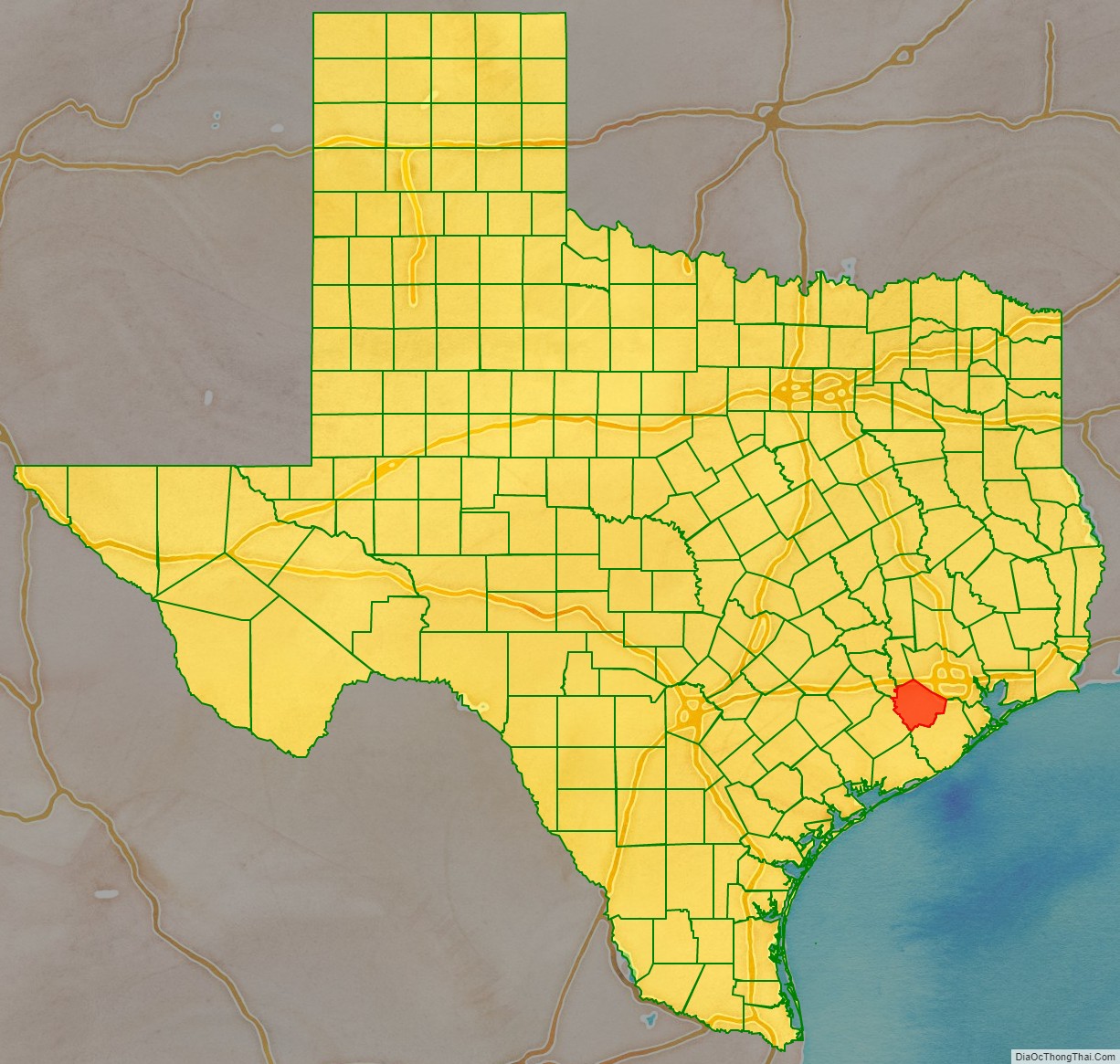

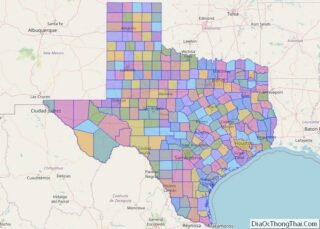

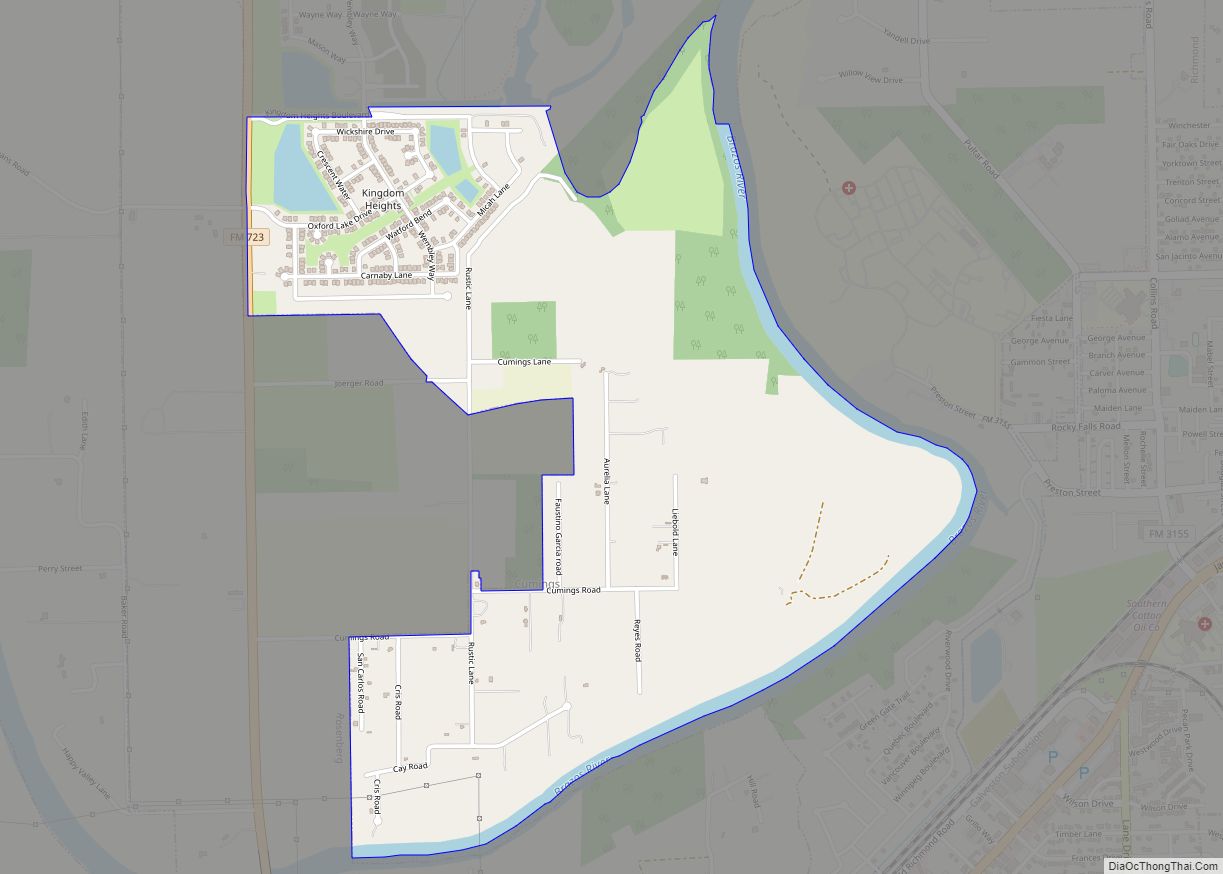

Fort Bend County location map. Where is Fort Bend County?

History

Before European settlement, the area was inhabited by Karankawa Indians. Spanish colonists generally did not reach the area during their colonization, settling more in South Texas.

After Mexico achieved independence from Spain, Anglo-Americans started entering from the east. In 1822, a group of Stephen F. Austin’s colonists, headed by William Travis, built a fort at the present site of Richmond. The fort was called Fort Bend because it was built in the bend of the Brazos River. The city of Richmond was incorporated under the Republic of Texas along with 19 other towns in 1837. Fort Bend County was created from parts of Austin, Harris, and Brazoria Counties in 1838.

Fort Bend developed a plantation economy based on cotton as the commodity crop. Planters had numerous African-American slaves as laborers. By the 1850s, Fort Bend was one of six majority-black counties in Texas. In 1860, the slave population totaled 4,127, more than twice that of the 2,016 whites. Few free Blacks lived there, as Texas refused them entry.

While the area began to attract white immigrants in the late 19th century, it remained majority-Black during and after Reconstruction. Whites endeavored to control freedmen and their descendants through violence and intimidation. Freedmen and their sympathizers supported the Republican Party because of emancipation, electing their candidates to office. The state legislature was still predominately white. By the 1880s, most white residents belonged to the Democratic Party. Factional tensions were fierce, as political elements split largely along racial lines. The Jaybirds, representing the majority of the Whites, struggled to regain control from the Woodpeckers, who were made up of some whites who were consistently elected to office by the majority of African Americans, as several had served as Republican officials during Reconstruction.

Fort Bend County was the site of the Jaybird–Woodpecker War in 1888–89. After a few murders were committed, the political feud culminated in a gun battle at the courthouse on August 16, 1889, when several more people were killed and the Woodpeckers were routed from the county seat.

Governor Lawrence Sullivan Ross sent in militia forces and declared martial law. With his support, the Jaybirds ordered a list of certain Blacks and Woodpecker officials out of the county, overthrowing the local government. The Jaybirds took over county offices and established a “White-only pre-primary,” disenfranchising African Americans from the only competitive contests in the county. This device lasted until 1950, when Willie Melton and Arizona Fleming won a lawsuit against the practice in United States District Court, though it was overturned on appeal. In 1953, they ultimately won their suit when the Supreme Court of the United States declared the Jaybird primary unconstitutional in Terry v. Adams, the last of the white primary cases.

20th century to present

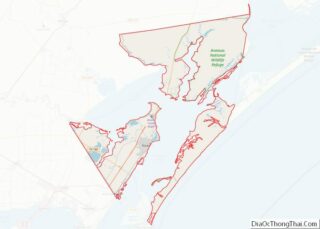

In the middle 1950s, Fort Bend and neighboring Galveston County were plagued by organized crime, which was involved with brothels and illegal casinos. Editor Clymer Wright of the Fort Bend Reporter joined with state officials and the Texas Rangers to rid the area of such corruption. Wright defied death threats to report on the issues and clean up the community. He soon sold his paper, now known as the Fort Bend Herald and Texas Coaster.

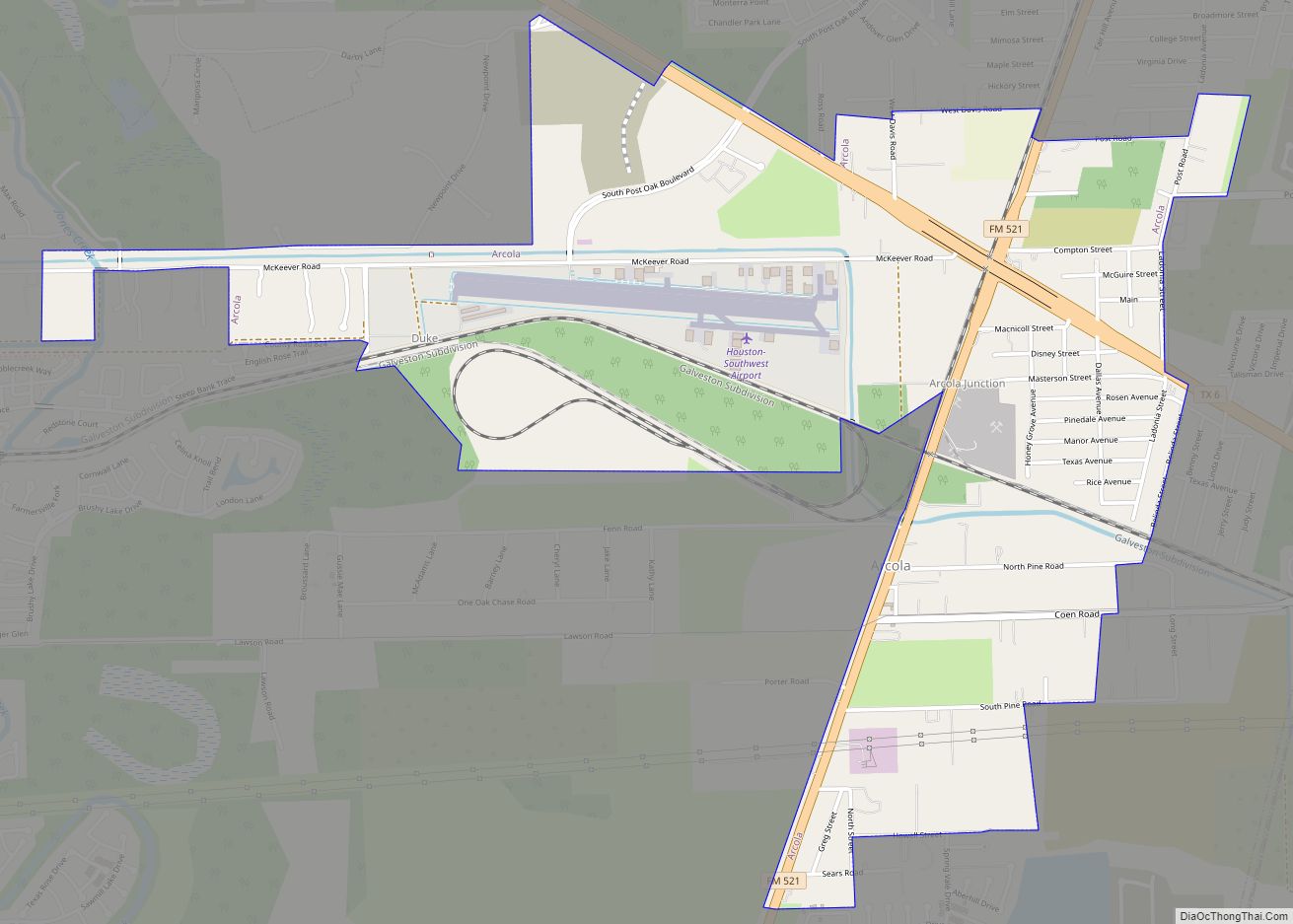

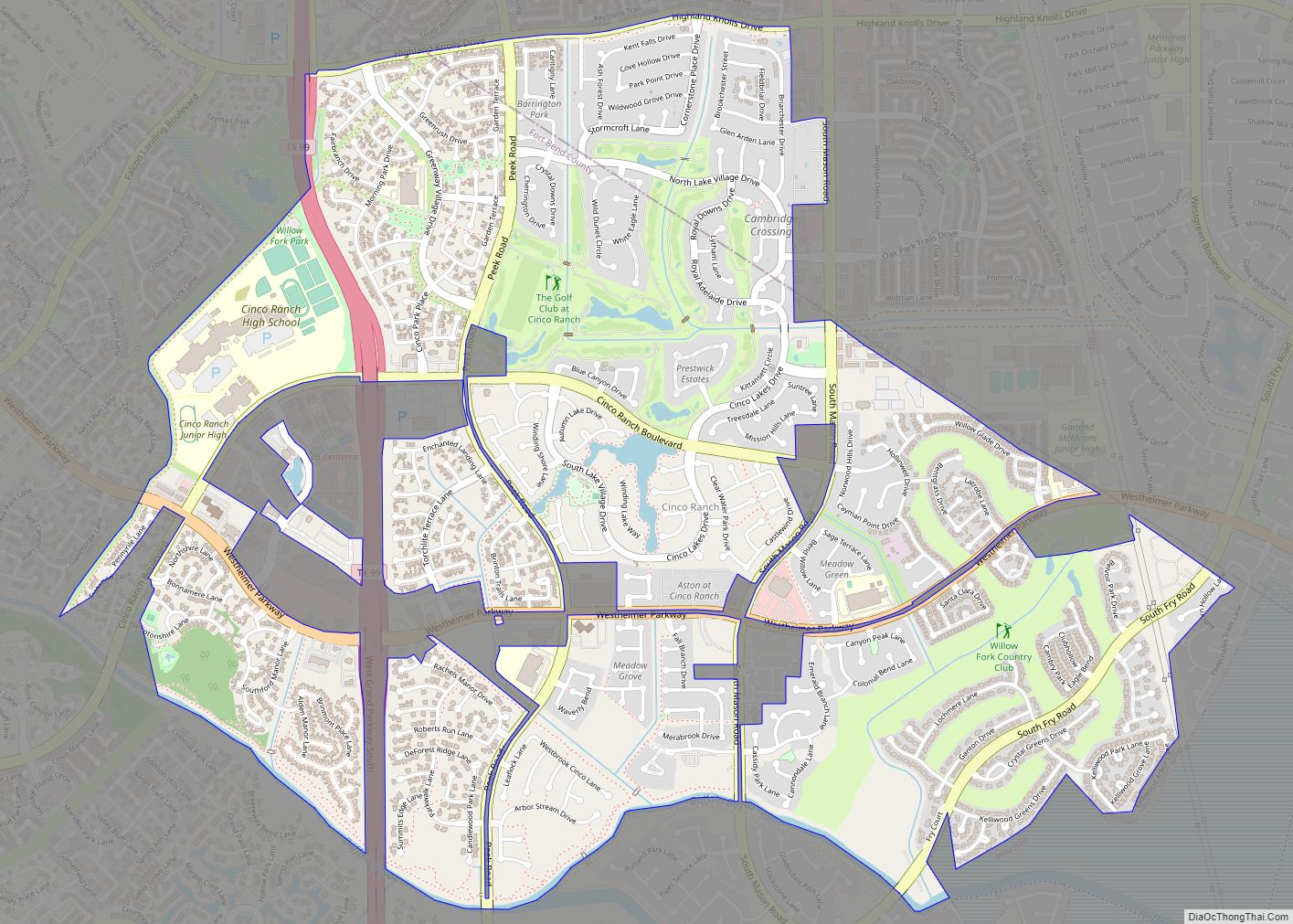

In the 1960s, the first of several master-planned communities that came to define the county were developed, marking the beginning of its transformation from a largely rural county dominated by railroad and oil and gas interests to a major suburban county dominated by service and manufacturing industries. Among the earliest such developments were Sugar Land’s Sugar Creek and Missouri City’s Quail Valley, whose golf course hosted the Houston Open during the 1973 and 1974 seasons of the PGA Tour. Another was First Colony in Sugar Land, a 9,700-acre development commenced in the 1970s by Houston developer Gerald D. Hines that eventually became the southwest Greater Houston area’s main retail hub, anchored by First Colony Mall and Sugar Land Town Square.

Since the 1980s, new communities have continued to develop, with Greatwood, New Territory, and Sienna (originally Sienna Plantation) among the more recent notable developments. In addition to continued development in the eastern part of the county around Sugar Land and Missouri City, the Greater Katy area began to experience rapid growth and expansion into Fort Bend County in the 1990s, led by the development of Cinco Ranch. By 2010, the county’s population exceeded 500,000, and it had become the second-largest county in the greater Houston area (behind Harris County).

In 2017, Hurricane Harvey caused significant flooding in Fort Bend County, leading to the evacuation of 200,000 residents and over 10,000 rescues. The unprecedented flooding, the result of record rainfall and overflow from the Brazos River and Barker Reservoir, resulted in damage to or destruction of over 6,800 homes in the county.

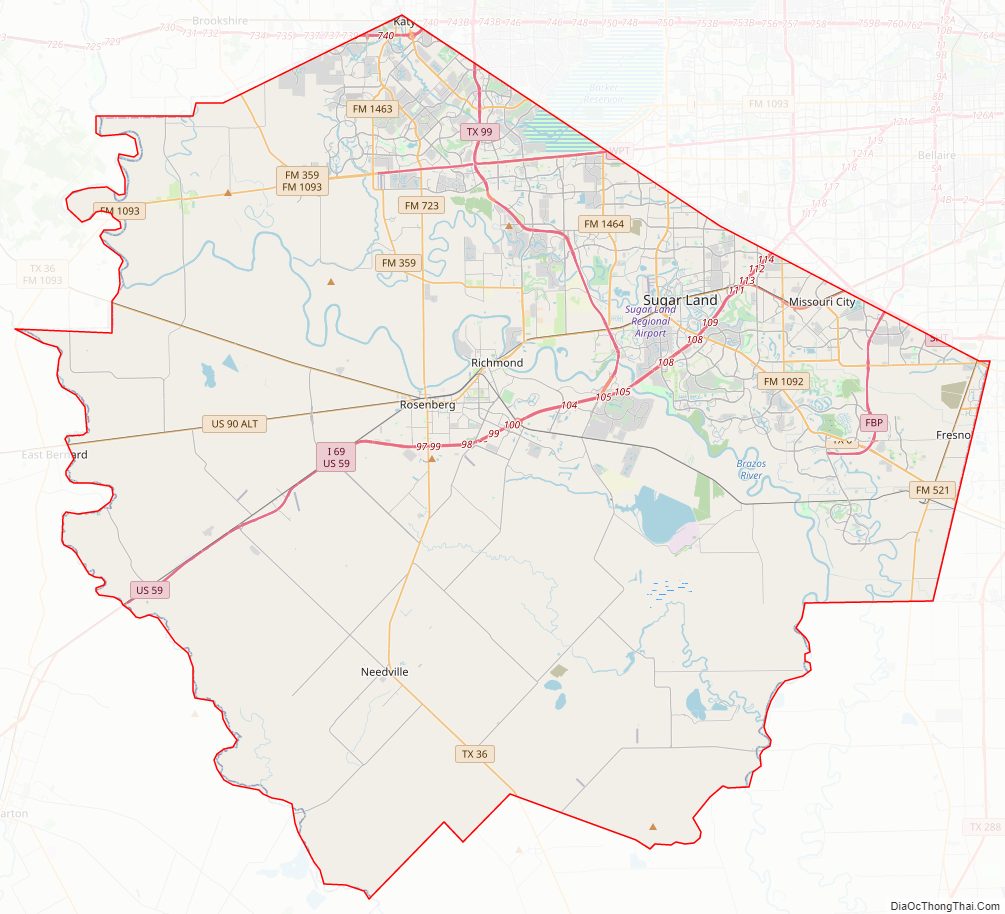

Fort Bend County Road Map

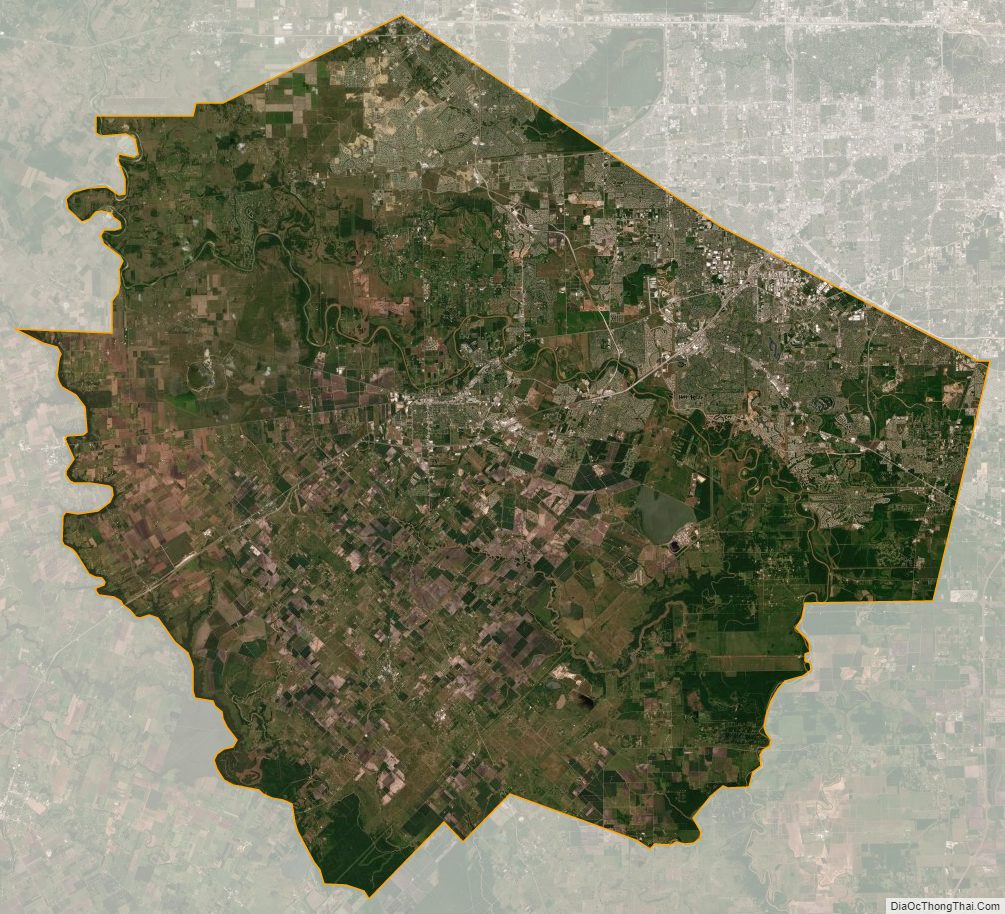

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 885 square miles (2,290 km), of which 24 square miles (62 km) (2.7%) are covered by water.

Adjacent counties

- Waller County (north)

- Harris County (northeast)

- Brazoria County (southeast)

- Wharton County (southwest)

- Austin County (northwest)