New Orleans (/ˈɔːrl(i)ənz/ OR-l(ee)ənz, /ɔːrˈliːnz/ or-LEENZ, locally /ˈɔːrlənz/ OR-lənz; French: La Nouvelle-Orléans [la nuvɛlɔʁleɑ̃] (listen), Spanish: Nueva Orleans) is a consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 according to the 2020 U.S. census, it is the most populous city in Louisiana, third most populous city in the Deep South, and the twelfth-most populous city in the southeastern United States. Serving as a major port, New Orleans is considered an economic and commercial hub for the broader Gulf Coast region of the United States.

New Orleans is world-renowned for its distinctive music, Creole cuisine, unique dialects, and its annual celebrations and festivals, most notably Mardi Gras. The historic heart of the city is the French Quarter, known for its French and Spanish Creole architecture and vibrant nightlife along Bourbon Street. The city has been described as the “most unique” in the United States, owing in large part to its cross-cultural and multilingual heritage. Additionally, New Orleans has increasingly been known as “Hollywood South” due to its prominent role in the film industry and in pop culture.

Founded in 1718 by French colonists, New Orleans was once the territorial capital of French Louisiana before becoming part of the United States in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. New Orleans in 1840 was the third most populous city in the United States, and it was the largest city in the American South from the Antebellum era until after World War II. The city has historically been very vulnerable to flooding, due to its high rainfall, low lying elevation, poor natural drainage, and proximity to multiple bodies of water. State and federal authorities have installed a complex system of levees and drainage pumps in an effort to protect the city.

New Orleans was severely affected by Hurricane Katrina in August 2005, which flooded more than 80% of the city, killed more than 1,800 people, and displaced thousands of residents, causing a population decline of over 50%. Since Katrina, major redevelopment efforts have led to a rebound in the city’s population. Concerns about gentrification, new residents buying property in formerly closely knit communities, and displacement of longtime residents have been expressed.

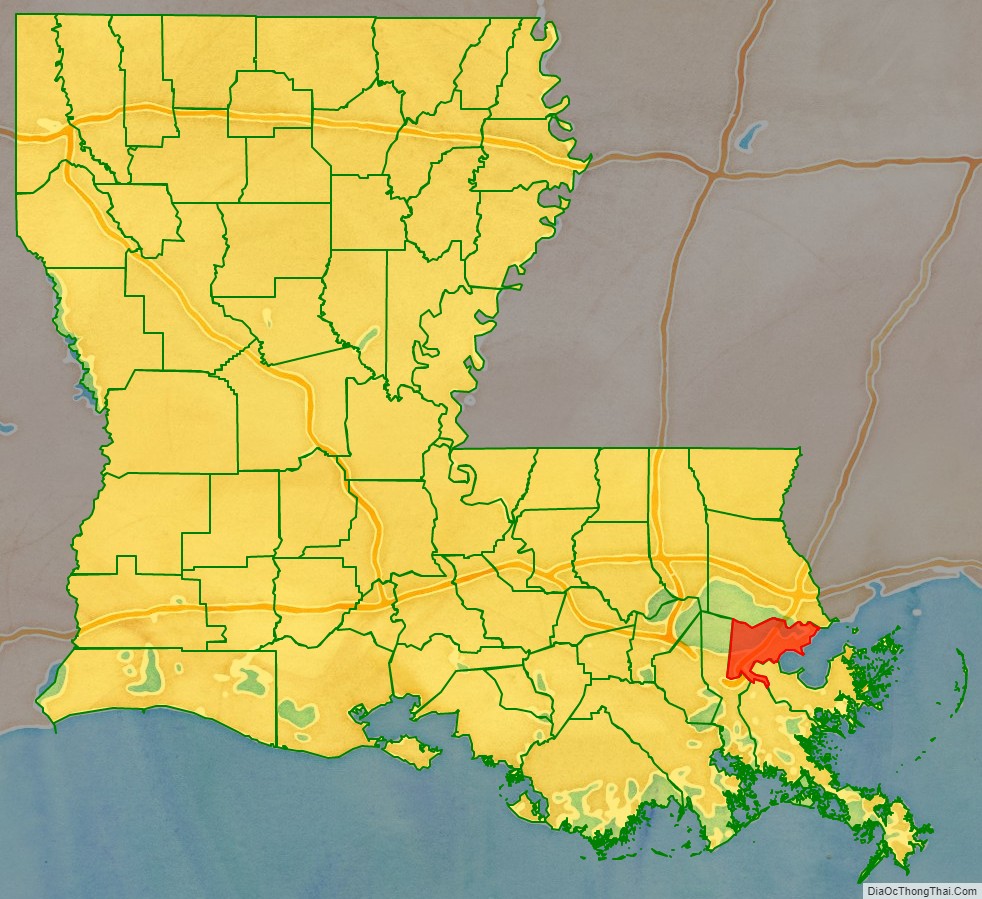

The city and Orleans Parish (French: paroisse d’Orléans) are coterminous. As of 2017, Orleans Parish is the third most populous parish in Louisiana, behind East Baton Rouge Parish and neighboring Jefferson Parish. The city and parish are bounded by St. Tammany Parish and Lake Pontchartrain to the north, St. Bernard Parish and Lake Borgne to the east, Plaquemines Parish to the south, and Jefferson Parish to the south and west.

The city anchors the larger Greater New Orleans metropolitan area, which had a population of 1,271,845 in 2020. Greater New Orleans is the most populous metropolitan statistical area in Louisiana and, since the 2020 census, has been the 46th most populous MSA in the United States.

| Name: | Orleans Parish |

|---|---|

| FIPS code: | 22-071 |

| State: | Louisiana |

| Founded: | 1807 |

| Named for: | Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (1674–1723) |

| Seat: | New Orleans |

| Total Area: | 350 sq mi (906 km²²) |

| Land Area: | 169.42 sq mi (438.80 km²) |

| Total Population: | 376,971 |

| Population Density: | 2,267/sq mi (875/km²) |

| Time zone: | UTC−6 (CST) |

| Summer Time Zone (DST): | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Website: | nola.gov |

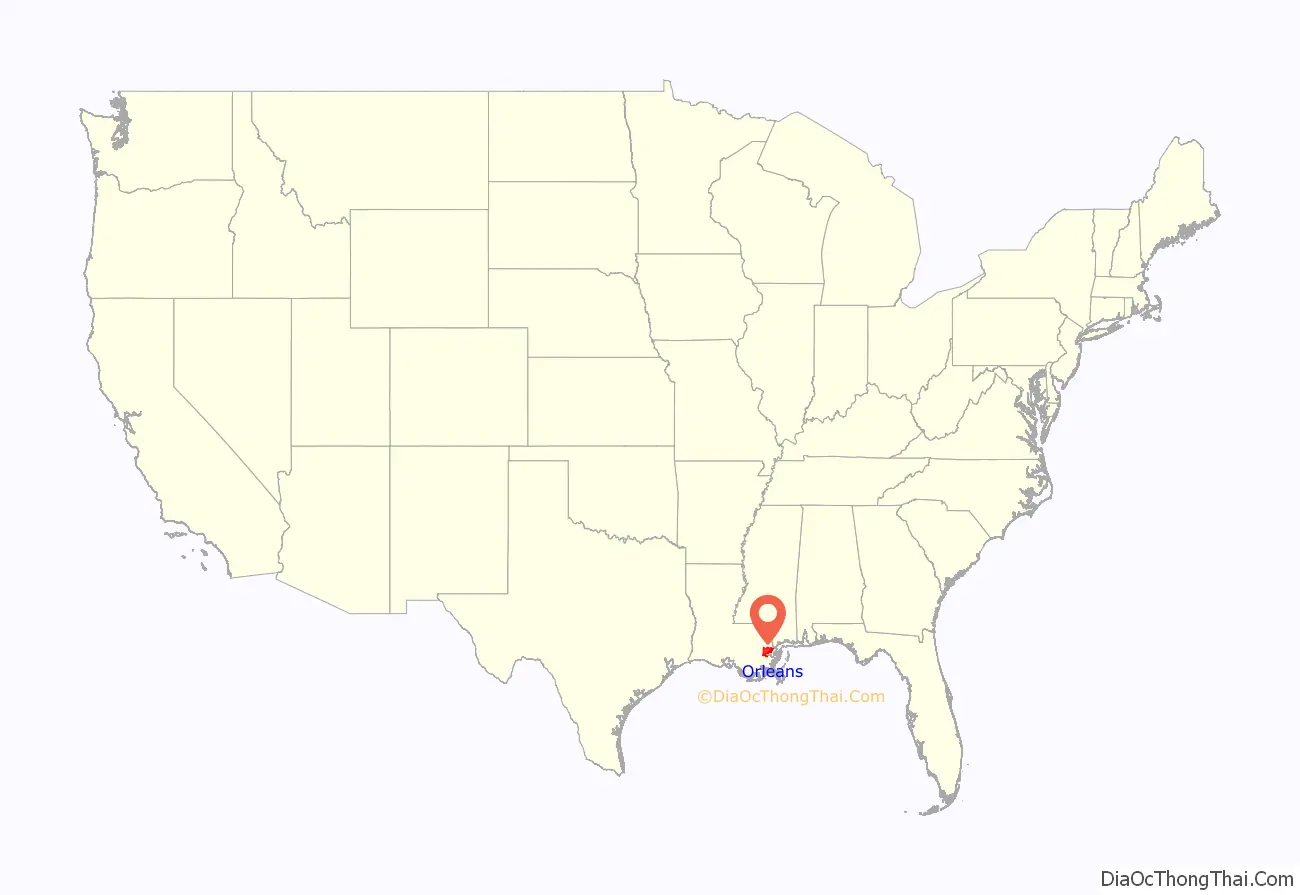

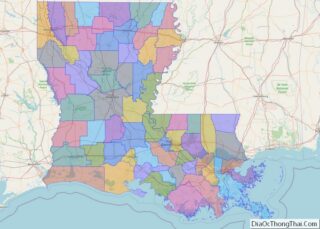

Orleans Parish location map. Where is Orleans Parish?

History

French–Spanish colonial era

La Nouvelle-Orléans (New Orleans) was founded in the spring of 1718 (May 7 has become the traditional date to mark the anniversary, but the actual day is unknown) by the French Mississippi Company, under the direction of Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, on land inhabited by the Chitimacha. It was named for Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, who was regent of the Kingdom of France at the time. His title came from the French city of Orléans. The French colony of Louisiana was ceded to the Spanish Empire in the 1763 Treaty of Paris, following France’s defeat by Great Britain in the Seven Years’ War. During the American Revolutionary War, New Orleans was an important port for smuggling aid to the American revolutionaries, and transporting military equipment and supplies up the Mississippi River. Beginning in the 1760s, Filipinos began to settle in and around New Orleans. Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid, Count of Gálvez successfully directed a southern campaign against the British from the city in 1779. Nueva Orleans (the name of New Orleans in Spanish) remained under Spanish control until 1803, when it reverted briefly to French rule. Nearly all of the surviving 18th-century architecture of the Vieux Carré (French Quarter) dates from the Spanish period, notably excepting the Old Ursuline Convent.

As a French colony, Louisiana faced struggles with numerous Native American tribes, who were navigating the competing interests of France, Spain, and England, as well as traditional rivals. Notably, the Natchez, whose traditional lands were along the Mississippi near the modern city of Natchez, Mississippi, had a series of wars culminating in the Natchez Revolt that began in 1729 with the Natchez overrunning Fort Rosalie. Approximately 230 French colonists were killed and the Natchez settlement destroyed, causing fear and concern in New Orleans and the rest of the territory. In retaliation, then-governor Étienne Perier launched a campaign to completely destroy the Natchez nation and its Native allies. By 1731, the Natchez people had been killed, enslaved, or dispersed among other tribes, but the campaign soured relations between France and the territory’s Native Americans leading directly into the Chickasaw Wars of the 1730s.

Relations with Louisiana’s Native American population remained a concern into the 1740s for governor Marquis de Vaudreuil. In the early 1740s traders from the Thirteen Colonies crossed into the Appalachian Mountains. The Native American tribes would now operate dependent on which of various European colonists would most benefit them. Several of these tribes and especially the Chickasaw and Choctaw would trade goods and gifts for their loyalty. The economic issue in the colony, which continued under Vaudreuil, resulted in many raids by Native American tribes, taking advantage of the French weakness. In 1747 and 1748, the Chickasaw would raid along the east bank of the Mississippi all the way south to Baton Rouge. These raids would often force residents of French Louisiana to take refuge in New Orleans proper.

Inability to find labor was the most pressing issue in the young colony. The colonists turned to sub-Saharan African slaves to make their investments in Louisiana profitable. In the late 1710s the transatlantic slave trade imported enslaved Africans into the colony. This led to the biggest shipment in 1716 where several trading ships appeared with slaves as cargo to the local residents in a one-year span.

By 1724, the large number of blacks in Louisiana prompted the institutionalizing of laws governing slavery within the colony. These laws required that slaves be baptized in the Roman Catholic faith, slaves be married in the church, and gave slaves no legal rights. The slave law formed in the 1720s is known as the Code Noir, which would bleed into the antebellum period of the American South as well. Louisiana slave culture had its own distinct Afro-Creole society that called on past cultures and the situation for slaves in the New World. Afro-Creole was present in religious beliefs and the Louisiana Creole language. The religion most associated with this period for was called Voodoo.

In the city of New Orleans an inspiring mixture of foreign influences created a melting pot of culture that is still celebrated today. By the end of French colonization in Louisiana, New Orleans was recognized commercially in the Atlantic world. Its inhabitants traded across the French commercial system. New Orleans was a hub for this trade both physically and culturally because it served as the exit point to the rest of the globe for the interior of the North American continent.

In one instance the French government established a chapter house of sisters in New Orleans. The Ursuline sisters after being sponsored by the Company of the Indies, founded a convent in the city in 1727. At the end of the colonial era, the Ursuline Academy maintained a house of 70 boarding and 100 day students. Today numerous schools in New Orleans can trace their lineage from this academy.

Another notable example is the street plan and architecture still distinguishing New Orleans today. French Louisiana had early architects in the province who were trained as military engineers and were now assigned to design government buildings. Pierre Le Blond de Tour and Adrien de Pauger, for example, planned many early fortifications, along with the street plan for the city of New Orleans. After them in the 1740s, Ignace François Broutin, as engineer-in-chief of Louisiana, reworked the architecture of New Orleans with an extensive public works program.

French policy-makers in Paris attempted to set political and economic norms for New Orleans. It acted autonomously in much of its cultural and physical aspects, but also stayed in communication with the foreign trends as well.

After the French relinquished West Louisiana to the Spanish, New Orleans merchants attempted to ignore Spanish rule and even re-institute French control on the colony. The citizens of New Orleans held a series of public meetings during 1765 to keep the populace in opposition of the establishment of Spanish rule. Anti-Spanish passions in New Orleans reached their highest level after two years of Spanish administration in Louisiana. On October 27, 1768, a mob of local residents, spiked the guns guarding New Orleans and took control of the city from the Spanish. The rebellion organized a group to sail for Paris, where it met with officials of the French government. This group brought with them a long memorial to summarize the abuses the colony had endured from the Spanish. King Louis XV and his ministers reaffirmed Spain’s sovereignty over Louisiana.

United States territorial era

The Third Treaty of San Ildefonso in 1800 restored French control of New Orleans and Louisiana, but Napoleon sold both to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Thereafter, the city grew rapidly with influxes of Americans, French, Creoles and Africans. Later immigrants were Irish, Germans, Poles and Italians. Major commodity crops of sugar and cotton were cultivated with slave labor on nearby large plantations.

Between 1791 and 1810, thousands of St. Dominican refugees from the Haitian Revolution, both whites and free people of color (affranchis or gens de couleur libres), arrived in New Orleans; a number brought their slaves with them, many of whom were native Africans or of full-blood descent. While Governor Claiborne and other officials wanted to keep out additional free black people, the French Creoles wanted to increase the French-speaking population. In addition to bolstering the territory’s French-speaking population, these refugees had a significant impact on the culture of Louisiana, including developing its sugar industry and cultural institutions.

As more refugees were allowed into the Territory of Orleans, St. Dominican refugees who had first gone to Cuba also arrived. Many of the white Francophones had been deported by officials in Cuba in 1809 as retaliation for Bonapartist schemes. Nearly 90 percent of these immigrants settled in New Orleans. The 1809 migration brought 2,731 whites, 3,102 free people of color (of mixed-race European and African descent), and 3,226 slaves of primarily African descent, doubling the city’s population. The city became 63 percent black, a greater proportion than Charleston, South Carolina‘s 53 percent at that time.

Battle of New Orleans

During the final campaign of the War of 1812, the British sent a force of 11,000 in an attempt to capture New Orleans. Despite great challenges, General Andrew Jackson, with support from the U.S. Navy, successfully cobbled together a force of militia from Louisiana and Mississippi, U.S. Army regulars, a large contingent of Tennessee state militia, Kentucky frontiersmen and local privateers (the latter led by the pirate Jean Lafitte), to decisively defeat the British, led by Sir Edward Pakenham, in the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815.

The armies had not learned of the Treaty of Ghent, which had been signed on December 24, 1814 (however, the treaty did not call for cessation of hostilities until after both governments had ratified it. The U.S. government ratified it on February 16, 1815). The fighting in Louisiana began in December 1814 and did not end until late January, after the Americans held off the Royal Navy during a ten-day siege of Fort St. Philip (the Royal Navy went on to capture Fort Bowyer near Mobile, before the commanders received news of the peace treaty).

Port

As a port, New Orleans played a major role during the antebellum period in the Atlantic slave trade. The port handled commodities for export from the interior and imported goods from other countries, which were warehoused and transferred in New Orleans to smaller vessels and distributed along the Mississippi River watershed. The river was filled with steamboats, flatboats and sailing ships. Despite its role in the slave trade, New Orleans at the time also had the largest and most prosperous community of free persons of color in the nation, who were often educated, middle-class property owners.

Dwarfing the other cities in the Antebellum South, New Orleans had the U.S.’ largest slave market. The market expanded after the United States ended the international trade in 1808. Two-thirds of the more than one million slaves brought to the Deep South arrived via forced migration in the domestic slave trade. The money generated by the sale of slaves in the Upper South has been estimated at 15 percent of the value of the staple crop economy. The slaves were collectively valued at half a billion dollars. The trade spawned an ancillary economy—transportation, housing and clothing, fees, etc., estimated at 13.5% of the price per person, amounting to tens of billions of dollars (2005 dollars, adjusted for inflation) during the antebellum period, with New Orleans as a prime beneficiary.

According to historian Paul Lachance,

After the Louisiana Purchase, numerous Anglo-Americans migrated to the city. The population doubled in the 1830s and by 1840, New Orleans had become the nation’s wealthiest and the third-most populous city, after New York and Baltimore. German and Irish immigrants began arriving in the 1840s, working as port laborers. In this period, the state legislature passed more restrictions on manumissions of slaves and virtually ended it in 1852.

In the 1850s, white Francophones remained an intact and vibrant community in New Orleans. They maintained instruction in French in two of the city’s four school districts (all served white students). In 1860, the city had 13,000 free people of color (gens de couleur libres), the class of free, mostly mixed-race people that expanded in number during French and Spanish rule. They set up some private schools for their children. The census recorded 81 percent of the free people of color as mulatto, a term used to cover all degrees of mixed race. Mostly part of the Francophone group, they constituted the artisan, educated and professional class of African Americans. The mass of blacks were still enslaved, working at the port, in domestic service, in crafts, and mostly on the many large, surrounding sugarcane plantations.

After growing by 45 percent in the 1850s, by 1860, the city had nearly 170,000 people. It had grown in wealth, with a “per capita income [that] was second in the nation and the highest in the South.” The city had a role as the “primary commercial gateway for the nation’s booming midsection.” The port was the nation’s third largest in terms of tonnage of imported goods, after Boston and New York, handling 659,000 tons in 1859.

Civil War–Reconstruction era

As the Creole elite feared, the American Civil War changed their world. In April 1862, following the city’s occupation by the Union Navy after the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip, Gen. Benjamin F. Butler – a respected Massachusetts lawyer serving in that state’s militia – was appointed military governor. New Orleans residents supportive of the Confederacy nicknamed him “Beast” Butler, because of an order he issued. After his troops had been assaulted and harassed in the streets by women still loyal to the Confederate cause, his order warned that such future occurrences would result in his men treating such women as those “plying their avocation in the streets”, implying that they would treat the women like prostitutes. Accounts of this spread widely. He also came to be called “Spoons” Butler because of the alleged looting that his troops did while occupying the city, during which time he himself supposedly pilfered silver flatware.

Significantly, Butler abolished French-language instruction in city schools. Statewide measures in 1864 and, after the war, 1868 further strengthened the English-only policy imposed by federal representatives. With the predominance of English speakers, that language had already become dominant in business and government. By the end of the 19th century, French usage had faded. It was also under pressure from Irish, Italian and German immigrants. However, as late as 1902 “one-fourth of the population of the city spoke French in ordinary daily intercourse, while another two-fourths was able to understand the language perfectly,” and as late as 1945, many elderly Creole women spoke no English. The last major French language newspaper, L’Abeille de la Nouvelle-Orléans (New Orleans Bee), ceased publication on December 27, 1923, after ninety-six years. According to some sources, Le Courrier de la Nouvelle Orleans continued until 1955.

As the city was captured and occupied early in the war, it was spared the destruction through warfare suffered by many other cities of the American South. The Union Army eventually extended its control north along the Mississippi River and along the coastal areas. As a result, most of the southern portion of Louisiana was originally exempted from the liberating provisions of the 1863 “Emancipation Proclamation” issued by President Abraham Lincoln. Large numbers of rural ex-slaves and some free people of color from the city volunteered for the first regiments of Black troops in the War. Led by Brigadier General Daniel Ullman (1810–1892), of the 78th Regiment of New York State Volunteers Militia, they were known as the “Corps d’Afrique.” While that name had been used by a militia before the war, that group was composed of free people of color. The new group was made up mostly of former slaves. They were supplemented in the last two years of the War by newly organized United States Colored Troops, who played an increasingly important part in the war.

Violence throughout the South, especially the Memphis Riots of 1866 followed by the New Orleans Riot in the same year, led Congress to pass the Reconstruction Act and the Fourteenth Amendment, extending the protections of full citizenship to freedmen and free people of color. Louisiana and Texas were put under the authority of the “Fifth Military District” of the United States during Reconstruction. Louisiana was readmitted to the Union in 1868. Its Constitution of 1868 granted universal male suffrage and established universal public education. Both blacks and whites were elected to local and state offices. In 1872, lieutenant governor P.B.S. Pinchback, who was of mixed race, succeeded Henry Clay Warmouth for a brief period as Republican governor of Louisiana, becoming the first governor of African descent of a U.S. state (the next African American to serve as governor of a U.S. state was Douglas Wilder, elected in Virginia in 1989). New Orleans operated a racially integrated public school system during this period.

Wartime damage to levees and cities along the Mississippi River adversely affected southern crops and trade. The federal government contributed to restoring infrastructure. The nationwide financial recession and Panic of 1873 adversely affected businesses and slowed economic recovery.

From 1868, elections in Louisiana were marked by violence, as white insurgents tried to suppress black voting and disrupt Republican Party gatherings. The disputed 1872 gubernatorial election resulted in conflicts that ran for years. The “White League”, an insurgent paramilitary group that supported the Democratic Party, was organized in 1874 and operated in the open, violently suppressing the black vote and running off Republican officeholders. In 1874, in the Battle of Liberty Place, 5,000 members of the White League fought with city police to take over the state offices for the Democratic candidate for governor, holding them for three days. By 1876, such tactics resulted in the white Democrats, the so-called Redeemers, regaining political control of the state legislature. The federal government gave up and withdrew its troops in 1877, ending Reconstruction.

Jim Crow era

Dixiecrats passed Jim Crow laws, establishing racial segregation in public facilities. In 1889, the legislature passed a constitutional amendment incorporating a “grandfather clause” that effectively disfranchised freedmen as well as the propertied people of color manumitted before the war. Unable to vote, African Americans could not serve on juries or in local office, and were closed out of formal politics for generations. The Southern U.S. was ruled by a white Democratic Party. Public schools were racially segregated and remained so until 1960.

New Orleans’ large community of well-educated, often French-speaking free persons of color (gens de couleur libres), who had been free prior to the Civil War, fought against Jim Crow. They organized the Comité des Citoyens (Citizens Committee) to work for civil rights. As part of their legal campaign, they recruited one of their own, Homer Plessy, to test whether Louisiana’s newly enacted Separate Car Act was constitutional. Plessy boarded a commuter train departing New Orleans for Covington, Louisiana, sat in the car reserved for whites only, and was arrested. The case resulting from this incident, Plessy v. Ferguson, was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1896. The court ruled that “separate but equal” accommodations were constitutional, effectively upholding Jim Crow measures.

In practice, African American public schools and facilities were underfunded across the South. The Supreme Court ruling contributed to this period as the nadir of race relations in the United States. The rate of lynchings of black men was high across the South, as other states also disfranchised blacks and sought to impose Jim Crow. Nativist prejudices also surfaced. Anti-Italian sentiment in 1891 contributed to the lynchings of 11 Italians, some of whom had been acquitted of the murder of the police chief. Some were shot and killed in the jail where they were detained. It was the largest mass lynching in U.S. history. In July 1900 the city was swept by white mobs rioting after Robert Charles, a young African American, killed a policeman and temporarily escaped. The mob killed him and an estimated 20 other blacks; seven whites died in the days-long conflict, until a state militia suppressed it.

Throughout New Orleans’ history, until the early 20th century when medical and scientific advances ameliorated the situation, the city suffered repeated epidemics of yellow fever and other tropical and infectious diseases.

20th century

New Orleans’ economic and

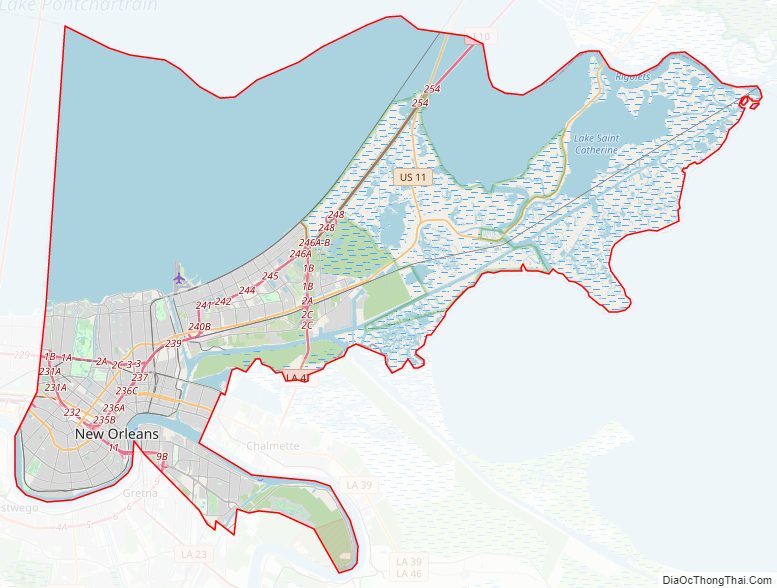

Orleans Parish Road Map

Geography

New Orleans is located in the Mississippi River Delta, south of Lake Pontchartrain, on the banks of the Mississippi River, approximately 105 miles (169 km) upriver from the Gulf of Mexico. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city’s area is 350 square miles (910 km), of which 169 square miles (440 km) is land and 181 square miles (470 km) (52%) is water. The area along the river is characterized by ridges and hollows.

Elevation

New Orleans was originally settled on the river’s natural levees or high ground. After the Flood Control Act of 1965, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built floodwalls and man-made levees around a much larger geographic footprint that included previous marshland and swamp. Over time, pumping of water from marshland allowed for development into lower elevation areas. Today, half of the city is at or below local mean sea level, while the other half is slightly above sea level. Evidence suggests that portions of the city may be dropping in elevation due to subsidence.

A 2007 study by Tulane and Xavier University suggested that “51%… of the contiguous urbanized portions of Orleans, Jefferson, and St. Bernard parishes lie at or above sea level,” with the more densely populated areas generally on higher ground. The average elevation of the city is currently between 1 foot (0.30 m) and 2 feet (0.61 m) below sea level, with some portions of the city as high as 20 feet (6 m) at the base of the river levee in Uptown and others as low as 7 feet (2 m) below sea level in the farthest reaches of Eastern New Orleans. A study published by the ASCE Journal of Hydrologic Engineering in 2016, however, stated:

The magnitude of subsidence potentially caused by the draining of natural marsh in the New Orleans area and southeast Louisiana is a topic of debate. A study published in Geology in 2006 by an associate professor at Tulane University claims:

The study noted, however, that the results did not necessarily apply to the Mississippi River Delta, nor the New Orleans metropolitan area proper. On the other hand, a report by the American Society of Civil Engineers claims that “New Orleans is subsiding (sinking)”:

In May 2016, NASA published a study which suggested that most areas were, in fact, experiencing subsidence at a “highly variable rate” which was “generally consistent with, but somewhat higher than, previous studies.”

Cityscape

The Central Business District is located immediately north and west of the Mississippi and was historically called the “American Quarter” or “American Sector.” It was developed after the heart of French and Spanish settlement. It includes Lafayette Square. Most streets in this area fan out from a central point. Major streets include Canal Street, Poydras Street, Tulane Avenue and Loyola Avenue. Canal Street divides the traditional “downtown” area from the “uptown” area.

Every street crossing Canal Street between the Mississippi River and Rampart Street, which is the northern edge of the French Quarter, has a different name for the “uptown” and “downtown” portions. For example, St. Charles Avenue, known for its street car line, is called Royal Street below Canal Street, though where it traverses the Central Business District between Canal and Lee Circle, it is properly called St. Charles Street. Elsewhere in the city, Canal Street serves as the dividing point between the “South” and “North” portions of various streets. In the local parlance downtown means “downriver from Canal Street”, while uptown means “upriver from Canal Street”. Downtown neighborhoods include the French Quarter, Tremé, the 7th Ward, Faubourg Marigny, Bywater (the Upper Ninth Ward), and the Lower Ninth