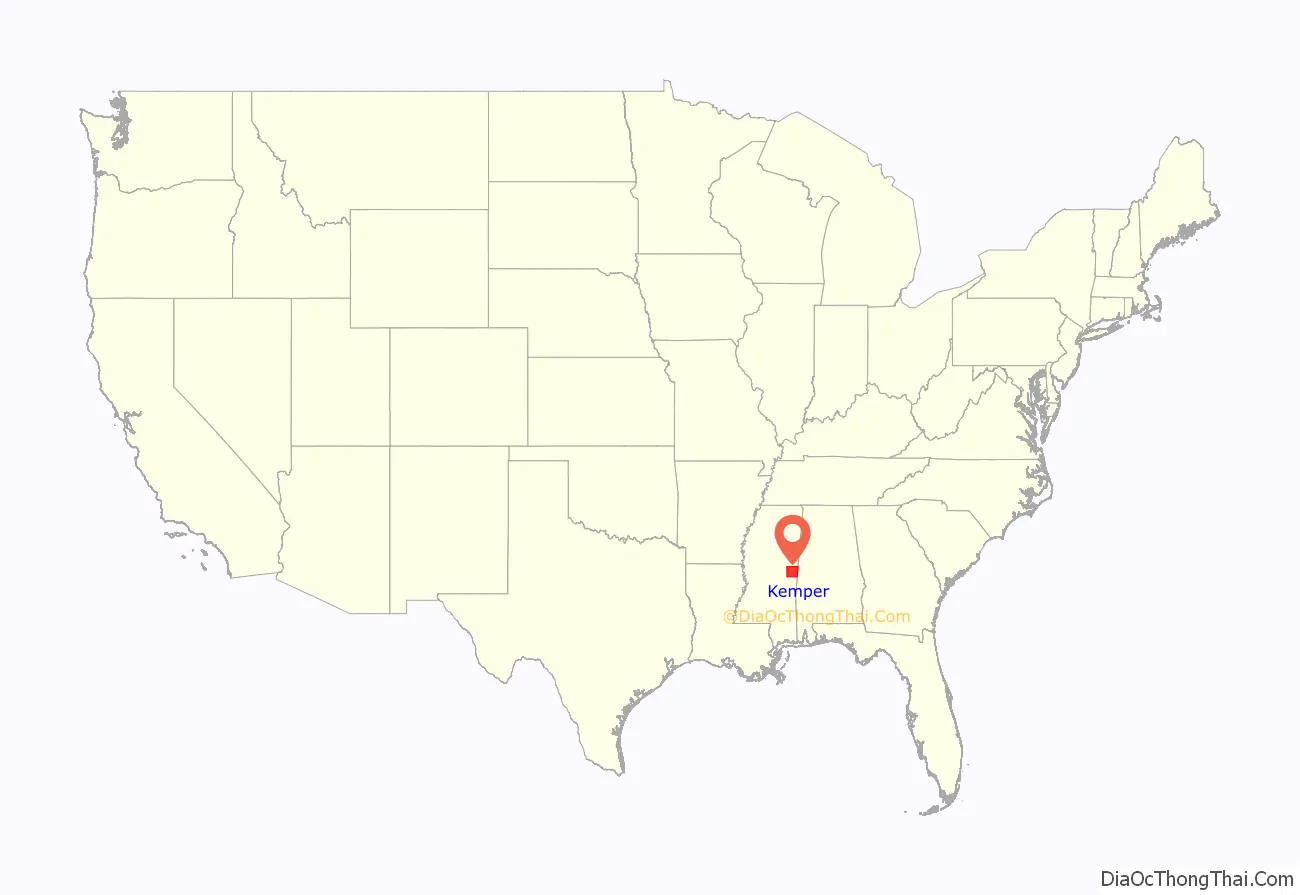

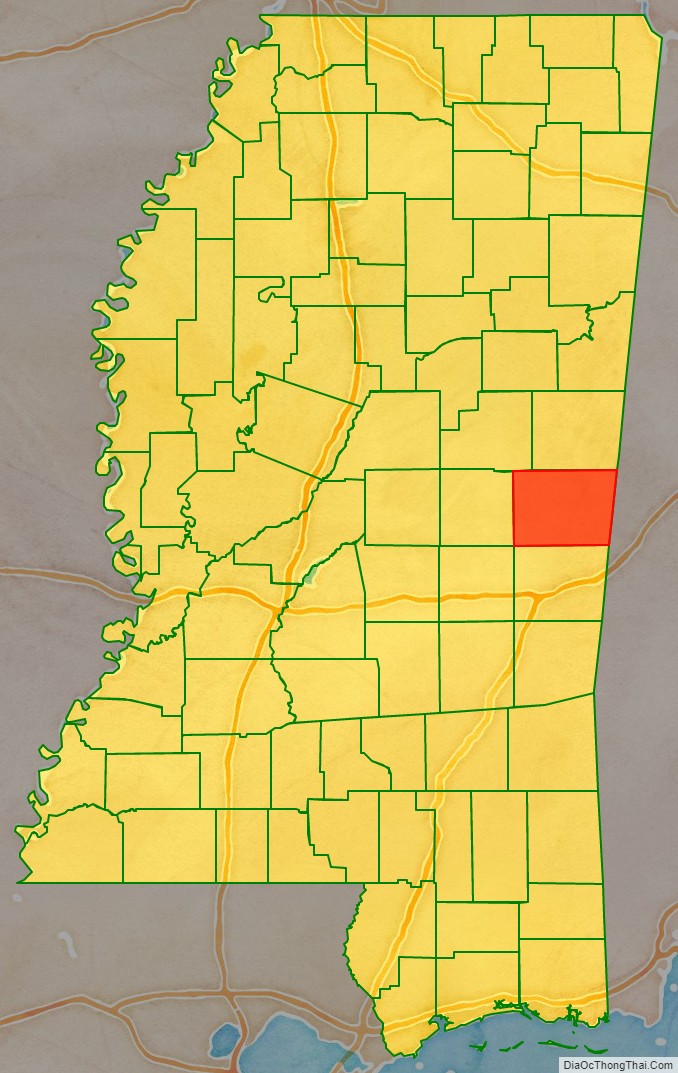

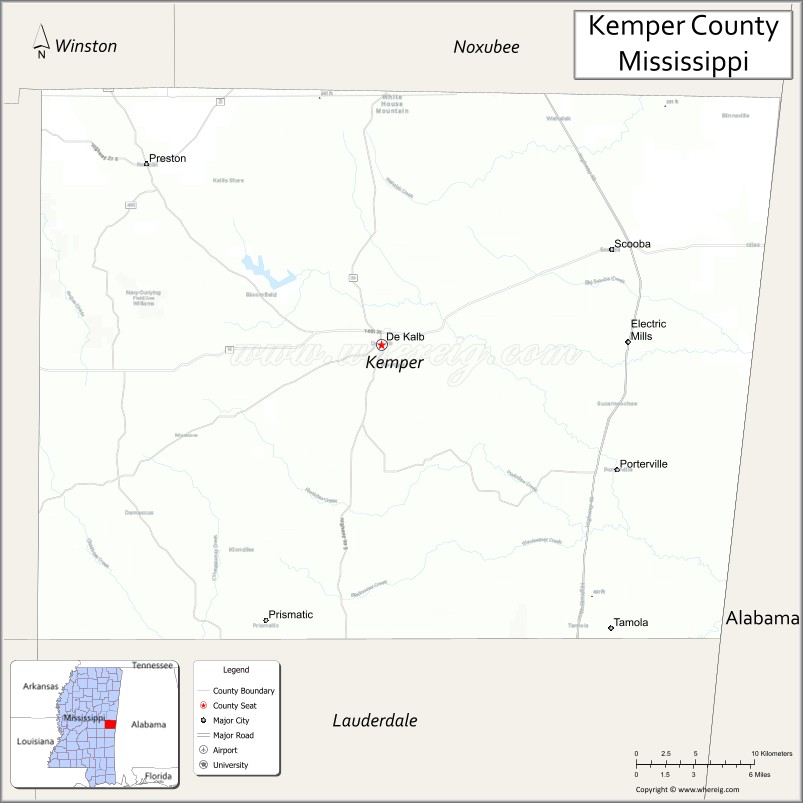

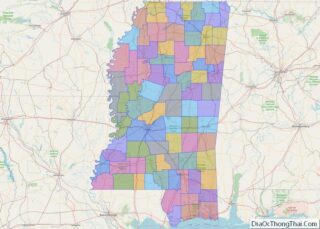

Kemper County is a county located on the central eastern border of the U.S. state of Mississippi. As of the 2020 census, the population was 8,988. Its county seat is De Kalb. The county is named in honor of Reuben Kemper.

The county is part of the Meridian, MS Micropolitan Statistical Area. In 2010 the Mississippi Public Service Commission approved construction of the Kemper Project, designed to use “clean coal” to produce electricity for 23 counties in the eastern part of the state. As of February 2017, it was not completed and had cost overruns. It is designed as a model project to use gasification and carbon-capture technologies at this scale.

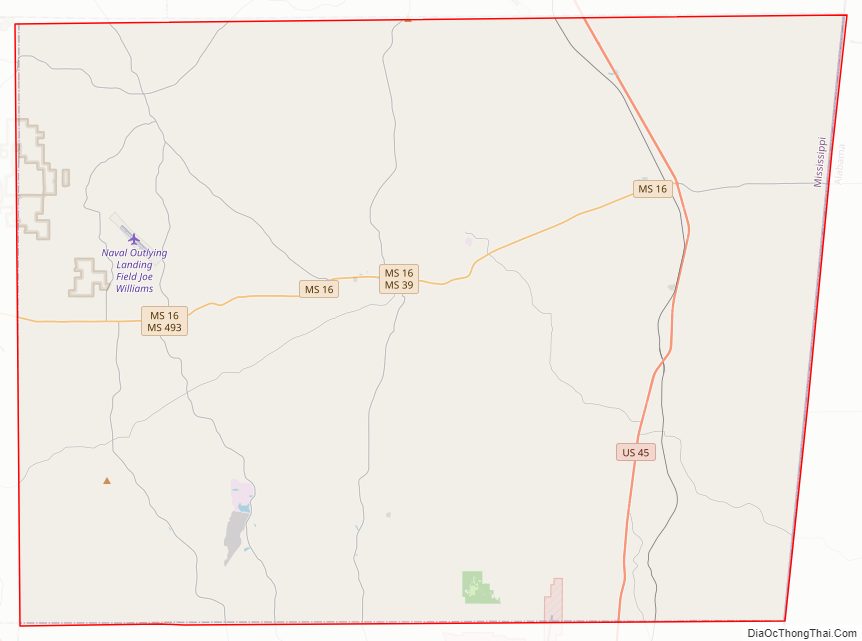

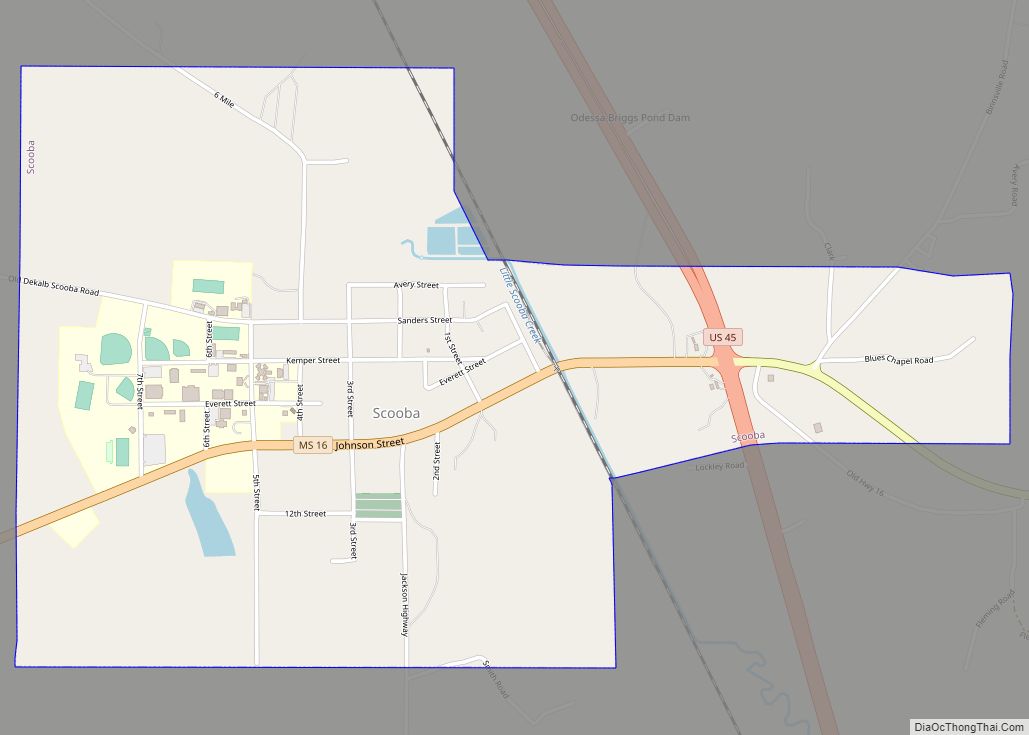

East Mississippi Community College is located in Kemper County in the town of Scooba, at the junction of US 45 and Mississippi Highway 16.

| Name: | Kemper County |

|---|---|

| FIPS code: | 28-069 |

| State: | Mississippi |

| Founded: | 1833 |

| Named for: | Reuben Kemper |

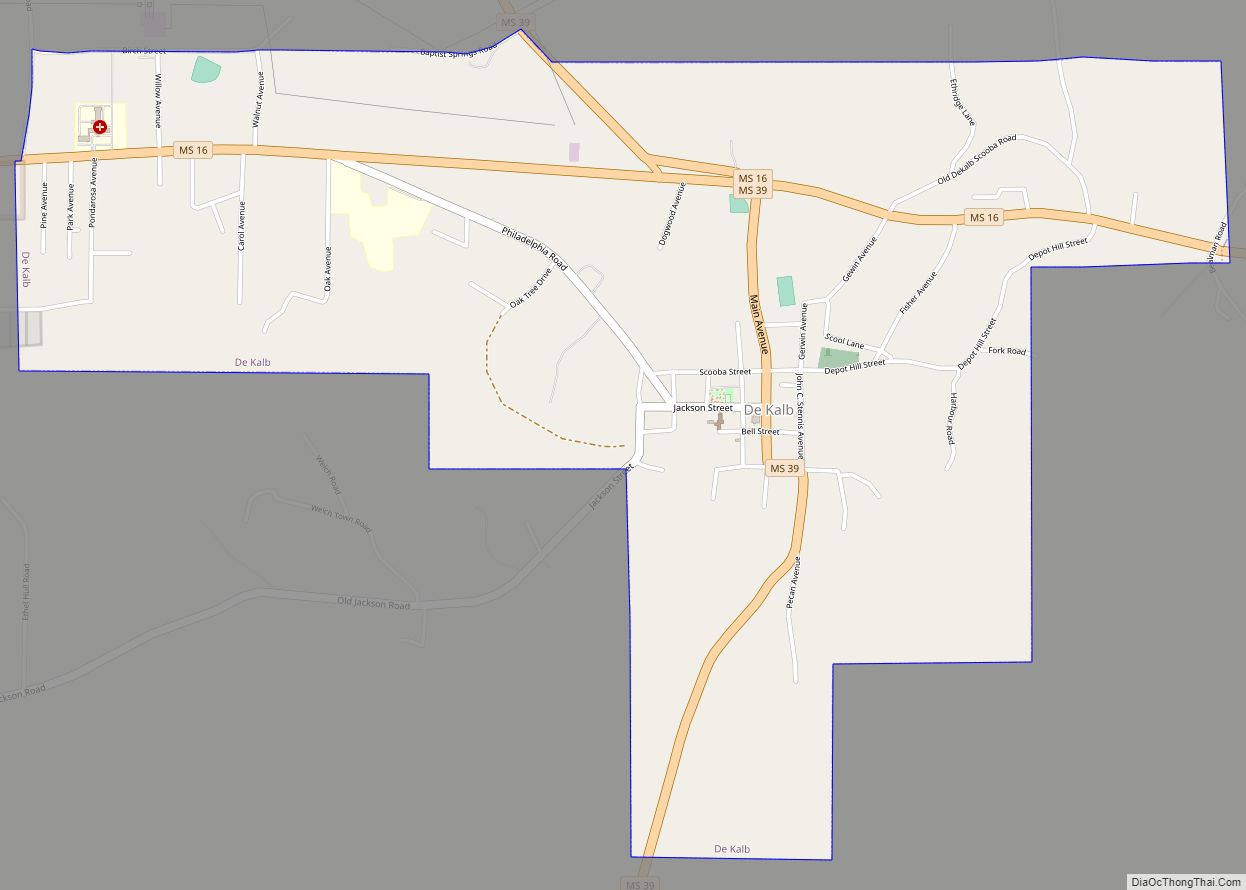

| Seat: | De Kalb |

| Largest town: | De Kalb |

| Total Area: | 767 sq mi (1,990 km²) |

| Land Area: | 766 sq mi (1,980 km²) |

| Total Population: | 8,988 |

| Population Density: | 12/sq mi (4.5/km²) |

| Time zone: | UTC−6 (Central) |

| Summer Time Zone (DST): | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Website: | www.kempercounty.ms |

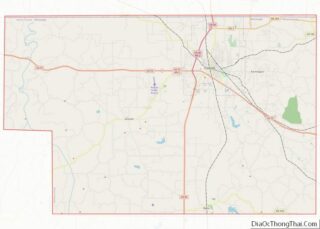

Kemper County location map. Where is Kemper County?

History

In the wake of the county’s founding, Abel Mastin Key served as the first circuit clerk. Land in the area was developed in the 19th century by white planters for cotton cultivation using enslaved African Americans. Blacks have comprised the majority of the county population since before the American Civil War. The county continues to be largely rural.

After the American Civil War and Reconstruction, racial violence increased as whites struggled to regain power over the majority population of freedmen and to suppress their voting. In the period from 1877 to 1950, Kemper County had 24 documented lynchings of African Americans, the third-highest of Mississippi counties. Hinds and Leflore counties had 29 and 48 lynchings, respectively, in this period. This form of racial terrorism was at its height in the decades around the turn of the 20th century, which followed the state’s disenfranchisement of most blacks in 1890 through creating barriers to voter registration.

In 1877 the Chisolm Massacre occurred, the murder by a mob of a judge, his children, and two of their friends while they were in protective custody in jail.

In 1890, blacks made up the majority of the county’ population: 10,084 blacks to 7,845 whites. They generally worked as sharecroppers or tenant farmers. Often illiterate, many of the sharecroppers were at a disadvantage in the annual accounting that was done by the landowners. Sometimes the planters had grocery stores on their property and required the sharecroppers to buy all their goods there, adding to their debt.

Beginning in late December 1906, there were several days of racial terror in the county. After violent incidents on the railroad between conductors and black passengers, whites attacked blacks at the rural towns of Wahalak and Scooba; by December 27, whites had killed a total of 13 blacks in rioting. The events started with a physical confrontation between a conductor and an African-American man on a Mobile & Ohio Railroad train. The conductor was cut, and he fatally shot two black men. George Simpson, another African American thought to be involved, escaped from the train. When captured in Wahalak by a posse, he killed a white constable and was quickly lynched by the other whites.

As reported by The New York Times,

Whites worried about blacks gathering to take revenge at Wahalak, where they had already been abused by lynchings. Local authorities called for state militia. Their commanding officer took his troops away from Wahalak, although there was still unrest, because he felt they were not being treated properly.

By the end of the day on December 26, white men in Scooba had killed another five black men. The county sheriff arrested several whites for these murders, and called for the state militia to go to Scooba. “All the men killed at Scooba today are said to be innocent of any crime, having been shot down merely as a matter of revenge by the rough whites.” There had been a conflict on another train, in which a black man mortally shot a conductor, George Harrison. The yardmaster shot and killed the African American. The rioting by whites in Scooba started after Harrison died. Governor James K. Vardaman went to Scooba with militia to establish control. He left a force of 20 there commanded by Adjutant General Fridge and returned to the state capital on the evening of December 27. That day the body of another murdered African-American man was found in the woods, bringing the total killed in Scooba to six.

In 1934, three African-American suspects in Kemper County were repeatedly whipped in order to force them to confess to murder. In Brown v. Mississippi (1936), the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled such forced confessions violated the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and were inadmissible at trial.

The peak of population in the rural county was in 1930. Mechanization of agriculture decreased the need for farm labor. From 1940 to 1970, the population declined markedly, as may be seen on the table below, as people moved to other areas for work. This was also the period of the second wave of the Great Migration, when 5 million African Americans moved out of the South to the North and especially to the West Coast, where the defense industry had many jobs, beginning during World War II.

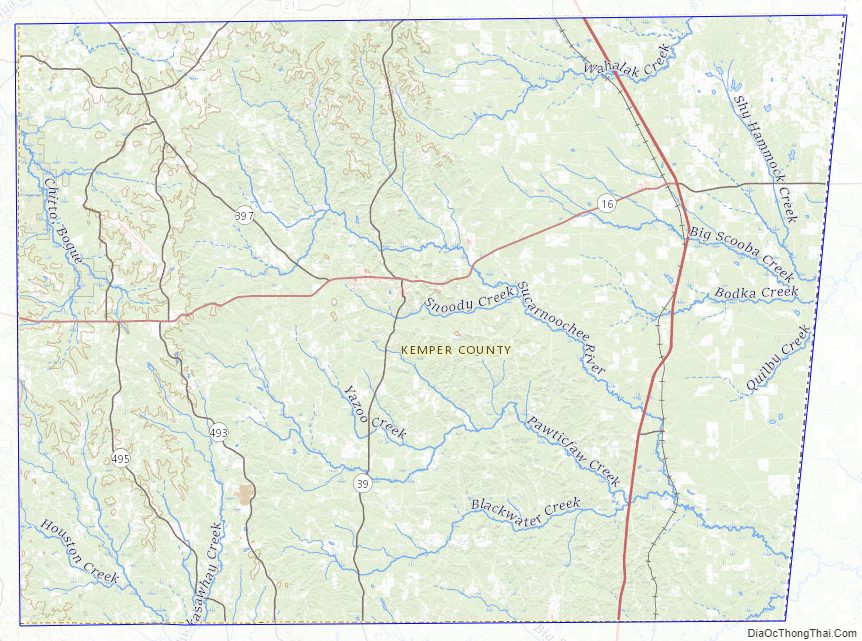

Kemper County Road Map

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 767 square miles (1,990 km), of which 766 square miles (1,980 km) is land and 0.8 square miles (2.1 km) (0.1%) is water.

Major highways

- U.S. Highway 45

- Mississippi Highway 16

- Mississippi Highway 21

- Mississippi Highway 39

Adjacent counties

- Noxubee County (north)

- Sumter County, Alabama (east)

- Lauderdale County (south)

- Neshoba County (west)

- Winston County (northwest)