Harrisonburg is an independent city in the Shenandoah Valley region of the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. It is also the county seat of the surrounding Rockingham County, although the two are separate jurisdictions. At the 2020 census, the population was 51,814. The Bureau of Economic Analysis combines the city of Harrisonburg with Rockingham County for statistical purposes into the Harrisonburg, Virginia Metropolitan Statistical Area, which had an estimated population of 126,562 in 2011.

Harrisonburg is home to James Madison University (JMU), a public research university with an enrollment of over 20,000 students, and Eastern Mennonite University (EMU), a private, Mennonite-affiliated liberal arts university. Although the city has no historical association with President James Madison, JMU was nonetheless named in his honor as Madison College in 1938 and renamed as James Madison University in 1977. EMU largely owes its existence to the sizable Mennonite population in the Shenandoah Valley, to which many Pennsylvania Dutch settlers arrived beginning in the mid-18th century in search of rich, unsettled farmland.

The city has become a bastion of ethnic and linguistic diversity in recent years. Over 1,900 refugees have been settled in Harrisonburg since 2002. As of 2014, Hispanics or Latinos of any race make up 19% of the city’s population. Harrisonburg City Public Schools (HCPS) students speak 55 languages in addition to English, with Spanish, Arabic, and Kurdish being the most common languages spoken. Over one-third of HCPS students are English as a second language (ESL) learners. Language learning software company Rosetta Stone was founded in Harrisonburg in 1992, and the multilingual “Welcome Your Neighbors” yard sign originated in Harrisonburg in 2016.

| Name: | Harrisonburg City |

|---|---|

| FIPS code: | 51-660 |

| State: | Virginia |

| Founded: | 1779 |

| Named for: | Thomas Harrison |

| Total Area: | 17.39 sq mi (45.04 km²) |

| Land Area: | 17.34 sq mi (44.91 km²) |

| Total Population: | 51,814 |

| Population Density: | 3,000/sq mi (1,200/km²) |

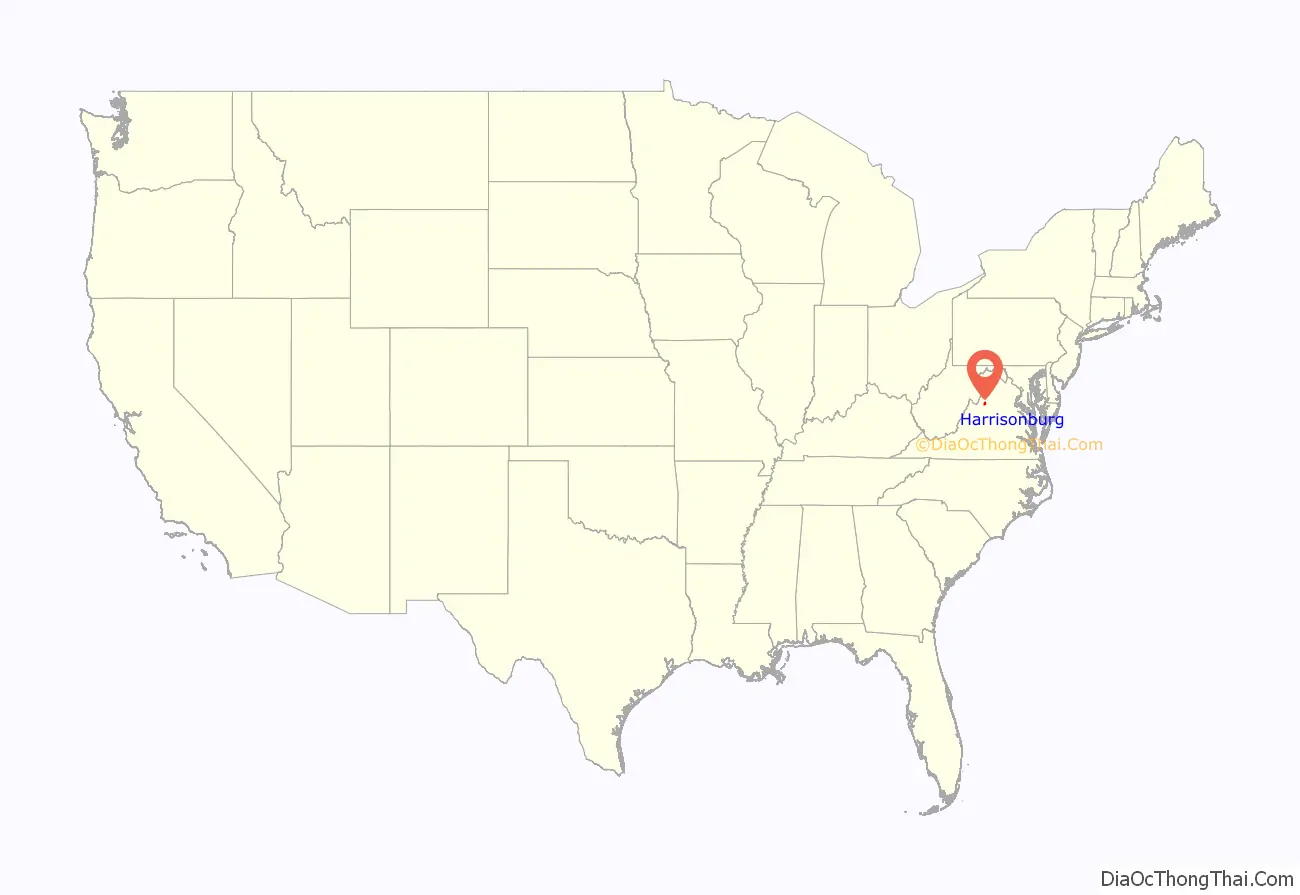

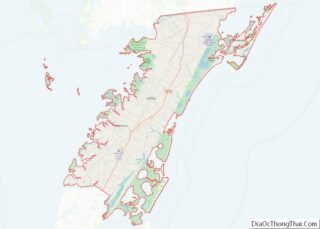

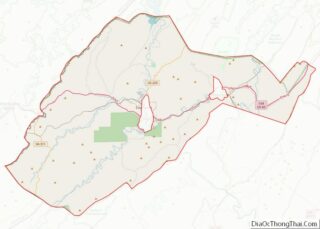

Harrisonburg City location map. Where is Harrisonburg City?

History

The earliest documented English exploration of the area prior to settlement was the Knights of the Golden Horseshoe Expedition, led by Lt. Gov. Alexander Spotswood, who reached Elkton, and whose rangers continued and in 1716 likely passed through what is now Harrisonburg.

Harrisonburg, previously known as “Rocktown,” was named for Thomas Harrison, a son of English settlers. In 1737, Harrison settled in the Shenandoah Valley, eventually laying claim to over 12,000 acres (4,900 ha) situated at the intersection of the Spotswood Trail and the main Native American road through the valley.

In 1779, Harrison deeded 2.5 acres (1.0 ha) of his land to the “public good” for the construction of a courthouse. In 1780, Harrison deeded an additional 50 acres (20 ha). This is the area now known as “Historic Downtown Harrisonburg.”

In 1849, trustees chartered a mayor–council form of government, although Harrisonburg was not officially incorporated as an independent city until 1916. Today, a council–manager government administers Harrisonburg.

On June 6, 1862, an American Civil War skirmish took place at Good’s Farm, Chestnut Ridge near Harrisonburg between the forces of the Union and the forces of the Confederacy at which the C.S. Army Brigadier General, Turner Ashby (1828–1862), was killed.

The city has expanded in size over the years.

On October 17, 2020, the city was the scene of a massive explosion and fire at a small shopping center at Miller Circle in the South Main St. area.

Newtown

When the slaves of the Shenandoah Valley were freed in 1865, they set up near modern-day Harrisonburg a town called Newtown. This settlement was eventually annexed by the independent city of Harrisonburg some years later, probably around 1892. Today, the old city of Newtown is in the Northeast section of Harrisonburg and which is referred to as Downtown Harrisonburg. It remains the home of the majority of Harrisonburg’s predominantly black churches, such as the First Baptist and Bethel AME. The modern Boys and Girls Club of Harrisonburg is located in the old Lucy Simms schoolhouse used for the black students in the days of segregation.

A large portion of this black neighborhood was dismantled in the 1960s when – in the name of urban renewal – the city government used federal redevelopment funds from the Housing Act of 1949 to force black families out of their homes and then bulldozed the neighborhood. This effort, called “Project R-4”, focused on the city blocks east of Main, north of Gay, west of Broad, and south of Johnson. This area makes up 32.5 acres. “Project R-16” is a smaller tag on project which focused on the 7.5 acres south of Gay street.

According to Bob Sullivan, an intern working in the city planner’s office in 1958, the city planner at the time, David Clark had to convince the city council that Harrisonburg even had slums. Newtown, a low socioeconomic status housing area, was declared a slum. Federal law mandated that the city needed to have a referendum on the issue before R4 could begin. The vote was close with 1,024 votes in favor and 978 against R4. Following the vote, the Harrisonburg Redevelopment and Housing Authority was established in 1955 to carry out the project. All of the members were white men. The project began and, due to eminent domain, the government could force the people of Newtown to sell their homes. They were offered rock bottom prices for their homes. Many people couldn’t afford a new home and had to move into public housing projects and become dependent on the government. Other families left Harrisonburg. It is estimated between 93 and 200 families were displaced.

In addition to families, many of the businesses of Newtown that were bought out could not afford to reestablish themselves. Locals say many prominent black businesses like the Colonnade which served as a pool hall, dance hall, community center, and tearoom were unable to reopen. Kline’s, a white-owned business, was actually one of the few businesses in the area that was able to reopen. The city later made $500,000 selling the seized property to redevelopers. Before the project, the area brought in $7000 in taxes annually. By 1976, The areas redeveloped in R4 and R16 were bringing in $45,000 in annual taxes. These profit gains led Lauren McKinney to regard the project as “one of only two ‘profitable’ redevelopment schemes in the state of Virginia.”

Cultural landmarks were also influenced by the projects. Although later rebuilt, The Old First Baptist Church of Harrisonburg was demolished. Newtown Cemetery, a Historic African American Cemetery, was also impacted. It appears no Burials were destroyed, however, the western boundary was paved over and several headstones now touch the street.

Infrastructure

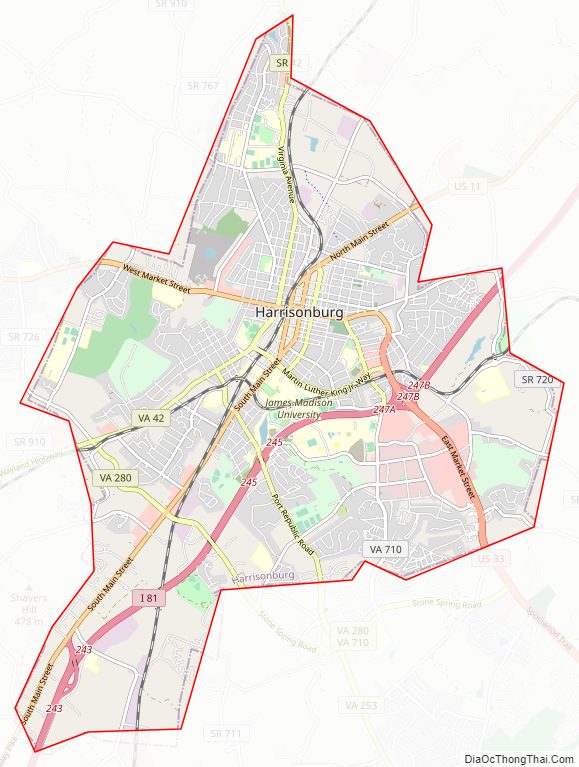

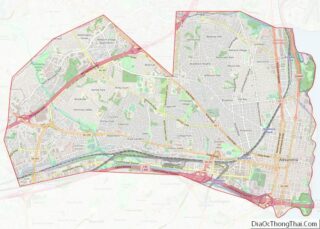

Major highways in Harrisonburg include Interstate 81, the main north–south highway in western Virginia and the Shenandoah Valley. Other significant roads serving the city include U.S. Route 11, U.S. Route 33, Virginia State Route 42, Virginia State Route 253 and Virginia State Route 280.

In early 2002, the Harrisonburg community discussed the possibility of creating a pedestrian mall downtown. Public meetings were held to discuss the merits and drawbacks of pursuing such a plan. Ultimately, the community decided to keep its Main Street open to traffic. From these discussions, however, a strong voice emerged from the community in support of downtown revitalization.

On July 1, 2003, Harrisonburg Downtown Renaissance was incorporated as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization with the mission of rejuvenating the downtown district.

In 2004, downtown was designated as the Harrisonburg Downtown Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places and a designated Virginia Main Street Community, with the neighboring Old Town Historic District residential community gaining historic district status in 2007. Several vacant buildings have been renovated and repurposed for new uses, such as the Hardesty-Higgins House and City Exchange, used for the Harrisonburg Tourist Center and high-end loft apartments, respectively.

In 2008, downtown Harrisonburg spent over $1 million in cosmetic and sidewalk infrastructure improvements (also called streetscaping and wayfinding projects). The City Council appropriated $500,000 for custom street signs to be used as “wayfinding signs” directing visitors to areas of interest around the city. Another $500,000 were used to upgrade street lighting, sidewalks, and landscaping along Main Street and Court Square.

In 2014, Downtown Harrisonburg was named a Great American Main Street by the National Main Street Association and downtown was designated the first culinary district in the commonwealth of Virginia.

Norfolk Southern also owns a small railyard in Harrisonburg. The Chesapeake and Western corridor from Elkton to Harrisonburg has very high volumes of grain and ethanol. The railroad serves two major grain elevators inside the city limits. In May 2017 Norfolk Southern 51T derailed in Harrisonburg spilling corn into Blacks Run. No one was injured.

Shenandoah Valley Railroad interchanges with the NS on south side of Harrisonburg and with CSX and Buckingham Branch Railroad in North Staunton.

Harrisonburg Transit provides public transportation in Harrisonburg. Virginia Breeze provides intercity bus service between Blacksburg, Harrisonburg, and Washington, D.C.

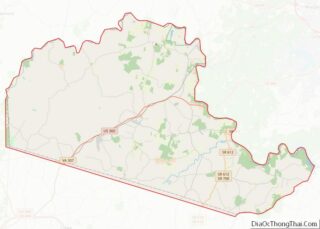

Harrisonburg City Road Map

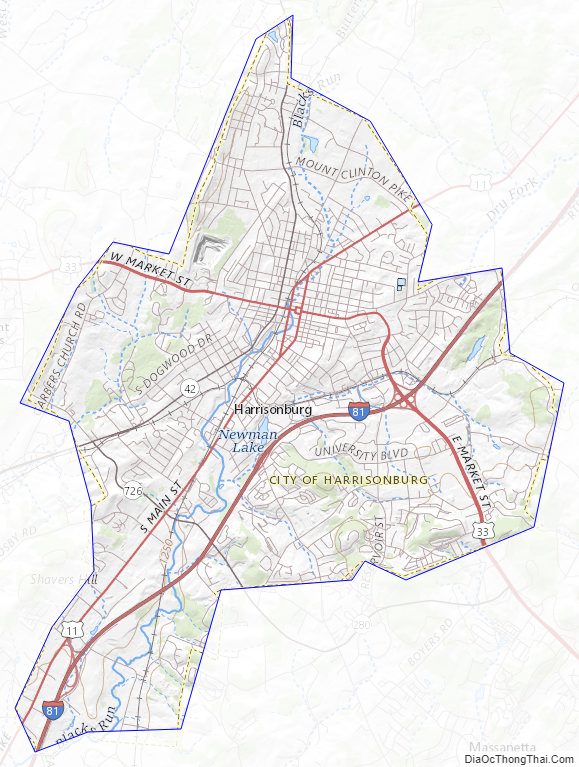

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 17.4 square miles (45.1 km), of which 17.3 square miles (44.8 km) is land and 0.1 square miles (0.3 km) (0.3%) is water. The City of Harrisonburg comprises six watersheds, with Blacks Run being the primary watershed with 8.67 miles of stream and a drainage area of over 9000 acres. The city also drains into the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. Harrisonburg is in the western part of the Shenandoah Valley, a portion of the Valley and Ridge physiographic province. Generally, the area is a rolling upland with local relief between 100 and 300 feet.