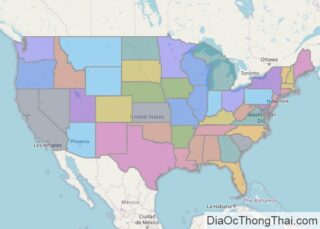

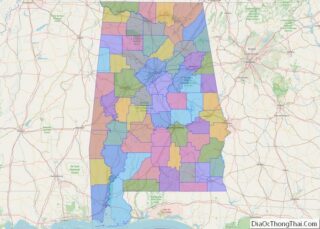

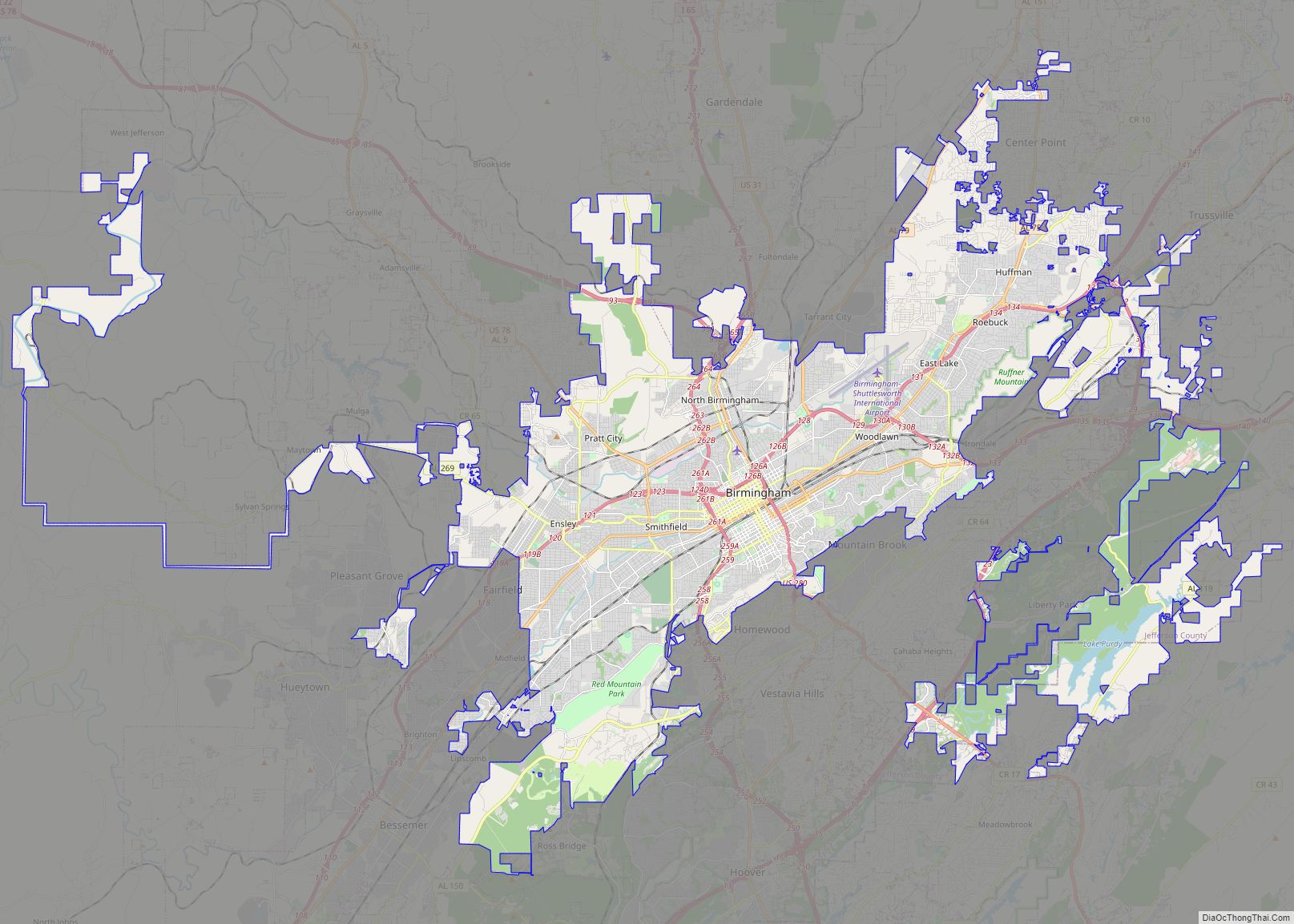

Jefferson County is the most populous county in the U.S. state of Alabama, located in the central portion of the state. As of the 2020 census, its population was 674,721. Its county seat is Birmingham. Its rapid growth as an industrial city in the 20th century, based on heavy manufacturing in steel and iron, established its dominance. Jefferson County is the central county of the Birmingham-Hoover, AL Metropolitan Statistical Area.

| Name: | Jefferson County |

|---|---|

| FIPS code: | 01-073 |

| State: | Alabama |

| Founded: | December 13, 1819 |

| Named for: | Thomas Jefferson |

| Seat: | Birmingham |

| Largest city: | Birmingham |

| Total Area: | 1,124 sq mi (2,910 km²) |

| Land Area: | 1,111 sq mi (2,880 km²) |

| Total Population: | 674,721 |

| Population Density: | 600/sq mi (230/km²) |

| Time zone: | UTC−6 (Central) |

| Summer Time Zone (DST): | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Website: | jeffconline.jccal.org |

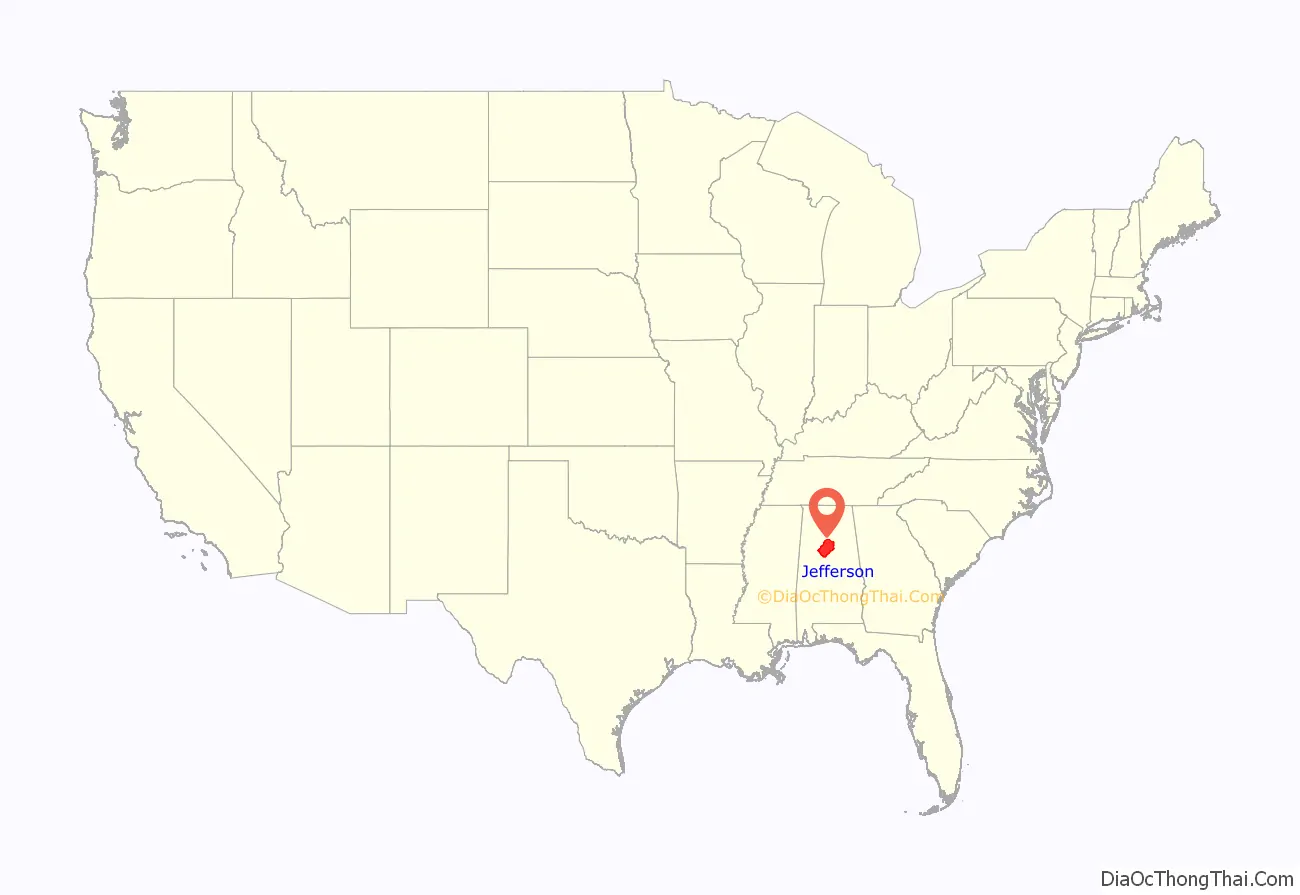

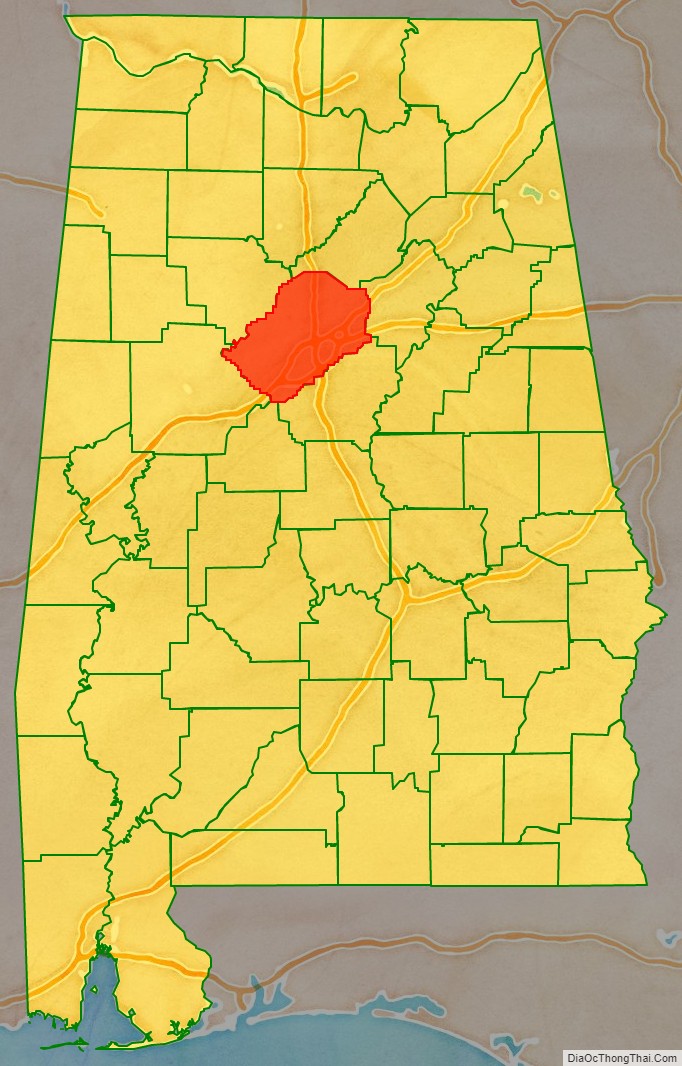

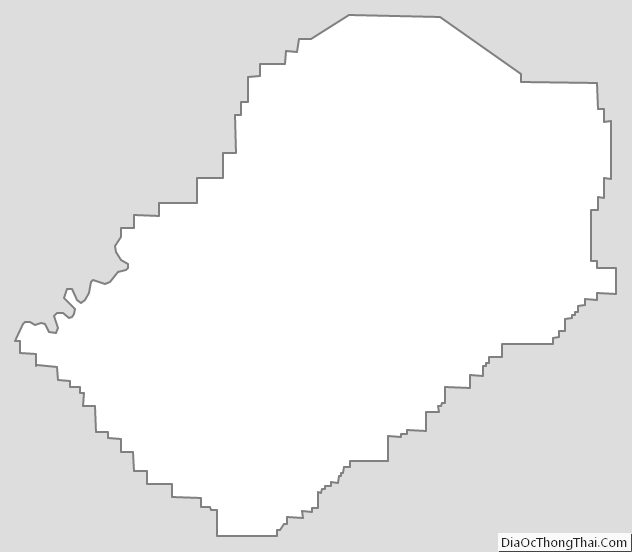

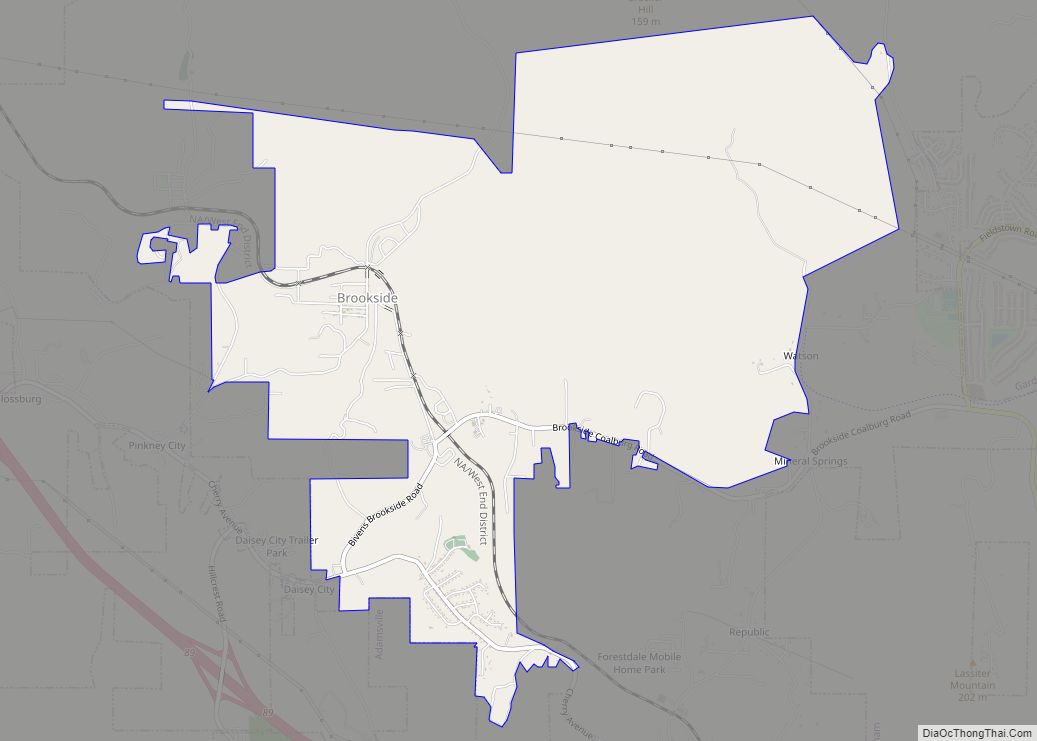

Jefferson County location map. Where is Jefferson County?

History

Jefferson County was established on December 13, 1819, by the Alabama Legislature. It was named in honor of former President Thomas Jefferson. The county is located in the north-central portion of the state, on the southernmost edge of the Appalachian Mountains. It is in the center of the (former) iron, coal, and limestone mining belt of the Southern United States.

Most of the original settlers were migrants of English ancestry from the Carolinas. Jefferson County has a land area of about 1,119 square miles (2,900 km). Early county seats were established first at Carrollsville (1819 – 21), then Elyton (1821 – 73).

Founded around 1871, Birmingham was named for the industrial English city of the same name in Warwickshire. That city had long been a center of iron and steel production in Great Britain. Birmingham was formed by the merger of three towns, including Elyton. It has continued to grow by annexing neighboring towns and villages, including North Birmingham.

As Birmingham industrialized, its growth accelerated, particularly after 1890. It attracted numerous rural migrants, both black and white, for its new jobs. It also attracted European immigrants. Despite the city’s rapid growth, for decades it was underrepresented in the legislature. Legislators from rural counties kept control of the legislature and, to avoid losing power, for decades refused to reapportion the seats or redistrict congressional districts. Birmingham could not get its urban needs addressed by the legislature.

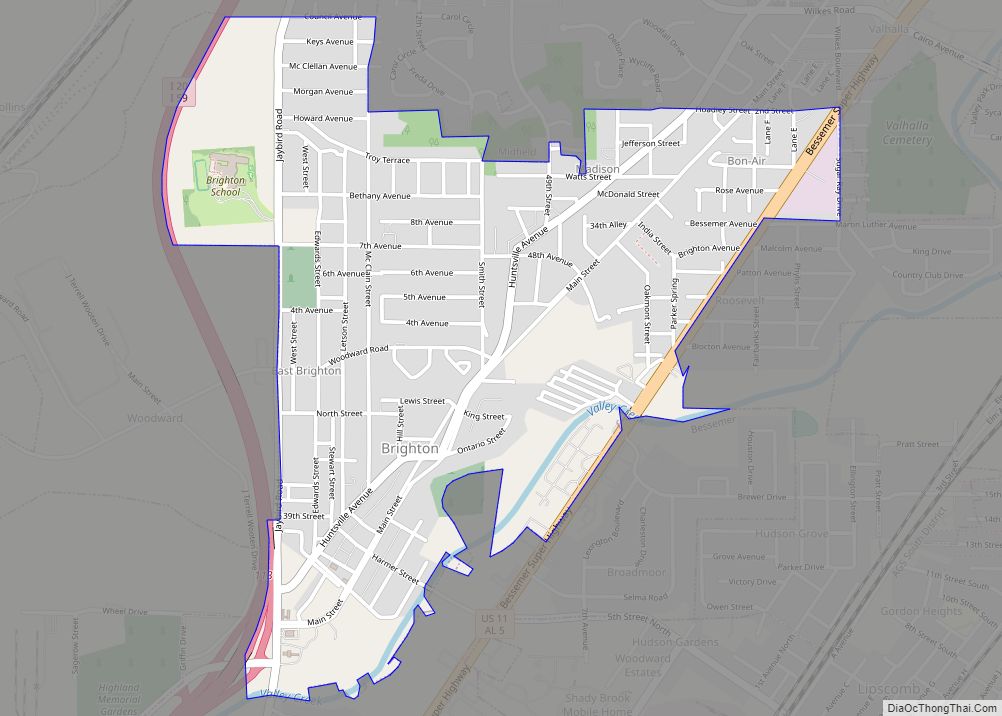

Nearby Bessemer, Alabama, located 16 miles by car to the southwest, also grew based on industrialization. It also attracted many workers. By the early decades of the 20th century, it had a majority-black population, but whites dominated politically and economically.

Racial tensions increased in the cities and state in the late 19th century as whites worked to maintain white supremacy. The white-dominated legislature passed a new constitution in 1901 that disenfranchised most blacks and many poor whites, excluding them totally from the political system. While they were nominally still eligible in the mid-20th century for jury duty, they were overwhelmingly excluded by white administrators from juries into the 1950s. Economic competition among the new workers in the city also raised tensions. It was a rough environment of mill and mine workers in Birmingham and Bessemer, and the Ku Klux Klan was active in the 20th century, often with many police being members into the 1950s and 1960s.

In a study of lynchings in the South from 1877 to 1950, Jefferson County is documented as having the highest number of lynchings of any county in Alabama. White mobs committed 29 lynchings in the county, most around the turn of the century at a time of widespread political suppression of blacks in the state. Notable incidents include 1889’s lynching of George Meadows.

Even after 1950, racial violence of whites against blacks continued. In the 1950s KKK chapters bombed black-owned houses in Birmingham to discourage residents moving into new middle-class areas. In that period, the city was referred to as “Bombingham.”

In 1963 African Americans led a movement in the city seeking civil rights, including integration of public facilities. The Birmingham campaign was known for the violence the city police used against non-violent protesters. In the late summer, city and business officials finally agreed in 1963 to integrate public facilities and hire more African Americans. This followed the civil rights campaign, which was based at the 16th Street Baptist Church, and an economic boycott of white stores that refused to hire blacks. Whites struck again: on a Sunday in September 1963, KKK members bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church, killing four young black girls and injuring many persons. The African-American community quickly rebuilt the damaged church. They entered politics in the city, county and state after the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed.

Sewer construction and bond swap controversy

In the 1990s, the county authorized and financed a massive overhaul of the county-owned sewer system, beginning in 1996. Sewerage and water rates had increased more than 300% in the 15 years before 2011, causing severe problems for the poor in Birmingham and the county.

Costs for the project increased due to problems in the financial area. In addition, county officials, encouraged by bribes by financial services companies, made a series of risky bond-swap agreements. Two extremely controversial undertakings by county officials in the 2000s resulted in the county having debt of $4 billion. The county eventually declared bankruptcy in 2011. It was the largest municipal bankruptcy in United States history at that time. Both the sewer project and its financing were scrutinized by federal prosecutors. By 2011, “six of Jefferson County’s former commissioners had been found guilty of corruption for accepting the bribes, along with 15 other officials.”

The controversial interest rate swaps, initiated in 2002 and 2003 by former Commission President Larry Langford (removed in 2011 as the mayor of Birmingham after his conviction at trial), were intended to lower interest payments. But they had the opposite effect, increasing the county’s indebtedness to the point that it had to declare bankruptcy. The bond swaps were the focus of an investigation by the United States Securities and Exchange Commission.

In late February 2008 Standard & Poor’s lowered the rating of Jefferson County bonds to “junk” status. The likelihood of the county filing for Chapter 9 bankruptcy protection was debated in the press. In early March 2008, Moody’s followed suit and indicated that it would also review the county’s ability to meet other bond obligations. On March 7, 2008, Jefferson County failed to post $184 million collateral as required under its sewer bond agreements, thereby moving into technical default.

In February 2011, Lesley Curwen of the BBC World Service interviewed David Carrington, the newly appointed president of the County Commission, about the risk of defaulting on bonds issued to finance “what could be the most expensive sewage system in history.” Carrington said there was “no doubt that people from Wall Street offered bribes” and “have to take a huge responsibility for what happened.” Wall Street investment banks, including JP Morgan and others, arranged complex financial deals using swaps. The fees and penalty charges increased the cost so the county in 2011 had $3.2 billion outstanding. Carrington said one of the problems was that elected officials had welcomed scheduling with very low early payments so long as peak payments occurred after they left office.

In 2011 the SEC awarded the county $75 million in compensation in relation to a judgment of “unlawful payments” against JP Morgan; in addition the company was penalized by having to forfeit $647 million of future fees.

2011 bankruptcy filing

Jefferson County filed for bankruptcy on November 9, 2011. This action was valued at $4.2 billion, with debts of $3.14 billion relating to sewer work; it was then the most costly municipal bankruptcy ever in the U.S. In 2013 it was surpassed by the Detroit bankruptcy in Michigan. The County requested Chapter 9 relief under federal statute 11 U.S.C. §921. The case was filed in the Northern District of Alabama Bankruptcy Court as case number 11-05736.

As of May 2012, Jefferson County had slashed expenses and reduced employment of county government workers by more than 700. The county emerged from bankruptcy in December 2013, following the approval of a bankruptcy plan by the United States bankruptcy court for the Northern District of Alabama, writing off more than $1.4 billion of the debt.

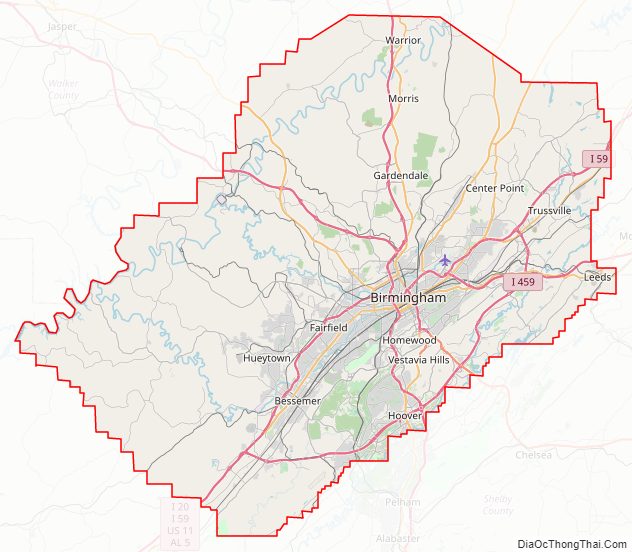

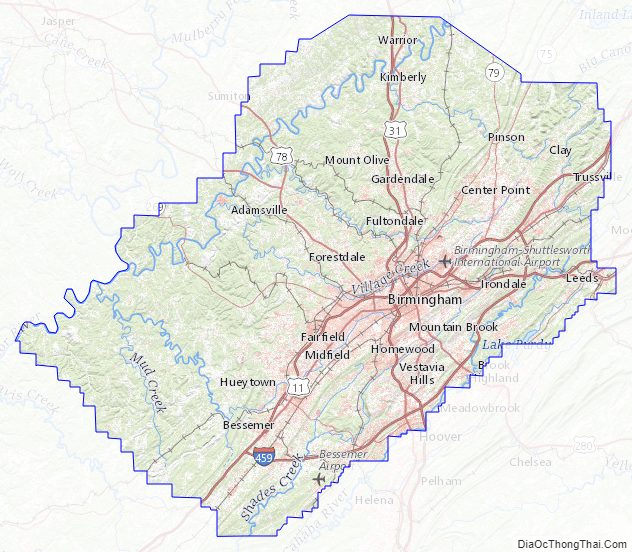

Jefferson County Road Map

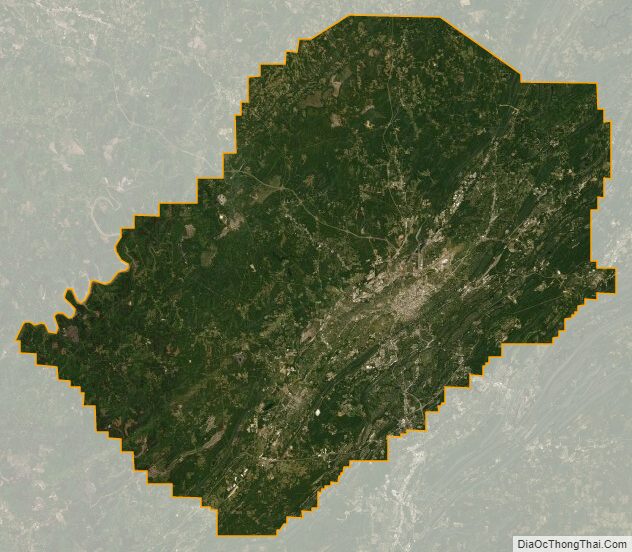

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 1,124 square miles (2,910 km), of which 1,111 square miles (2,880 km) is land and 13 square miles (34 km) (1.1%) is water. It is the fifth-largest county in Alabama by land area.

The county is located within the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians, with the highest point in the county being found at Shades Mountain, at an elevation of 1,150 ft. Another significant mountain located within the county is Red Mountain, which runs to the south of downtown Birmingham and separates the city from the suburb of Homewood. Many other mountains and valleys make up the majority of the county’s diverse geography.

The county is home to the Watercress Darter National Wildlife Refuge.

Adjacent counties

- Tuscaloosa County (west)

- Bibb County (southwest)

- Shelby County (south)

- Walker County (northwest)

- Blount County (northeast)

- St. Clair County (northeast)