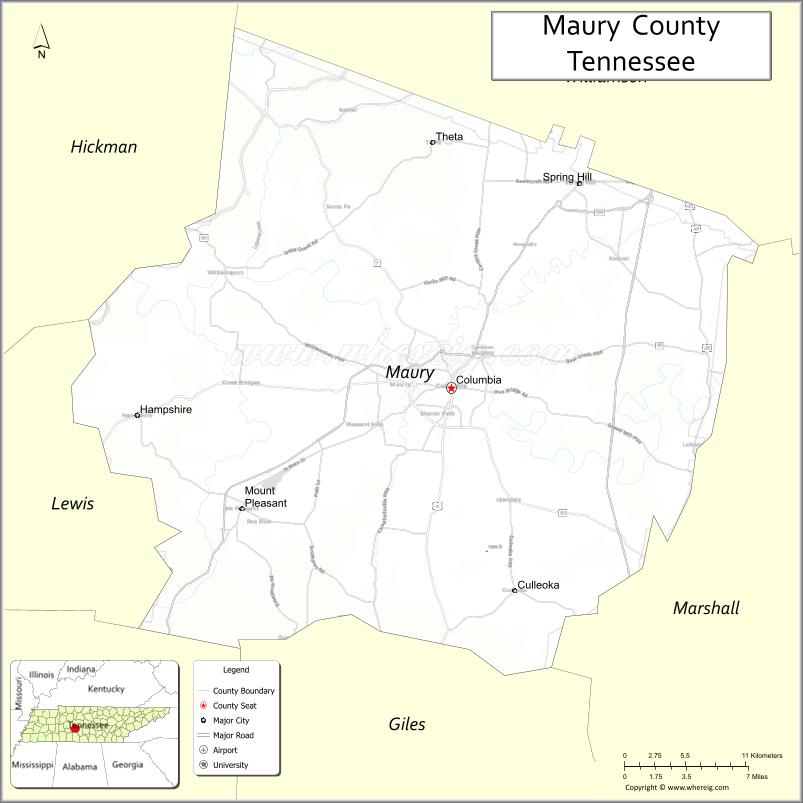

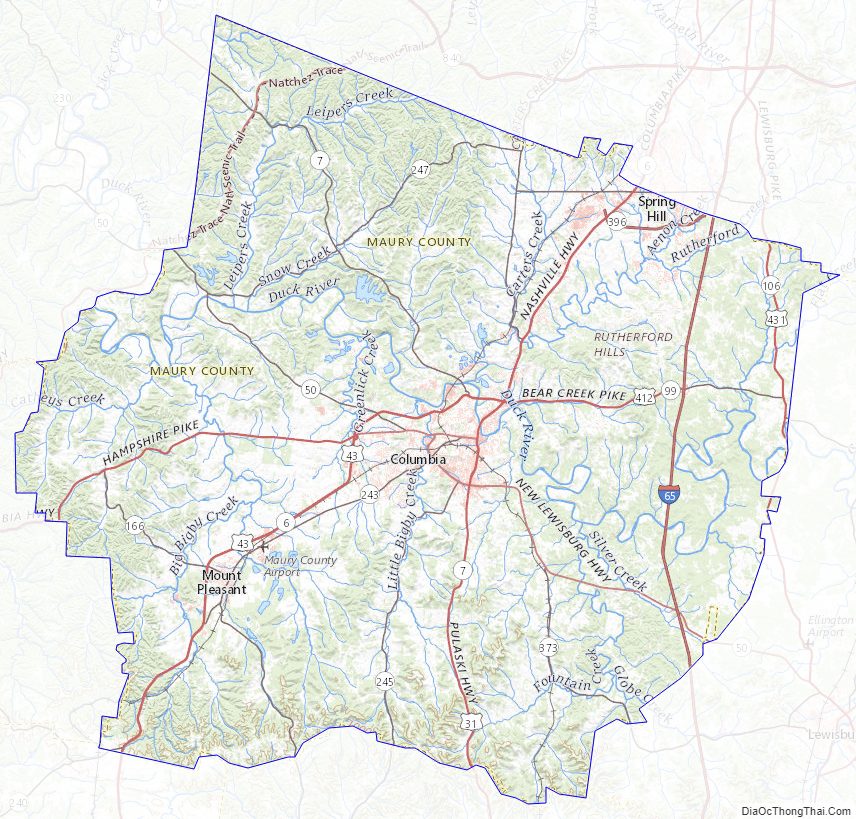

| Name: | Maury County |

|---|---|

| FIPS code: | 47-119 |

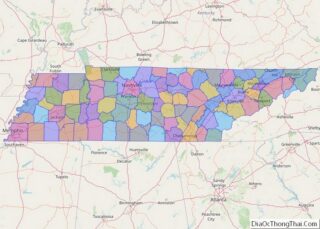

| State: | Tennessee |

| Founded: | 1807 |

| Named for: | Abram Poindexter Maury, Sr. |

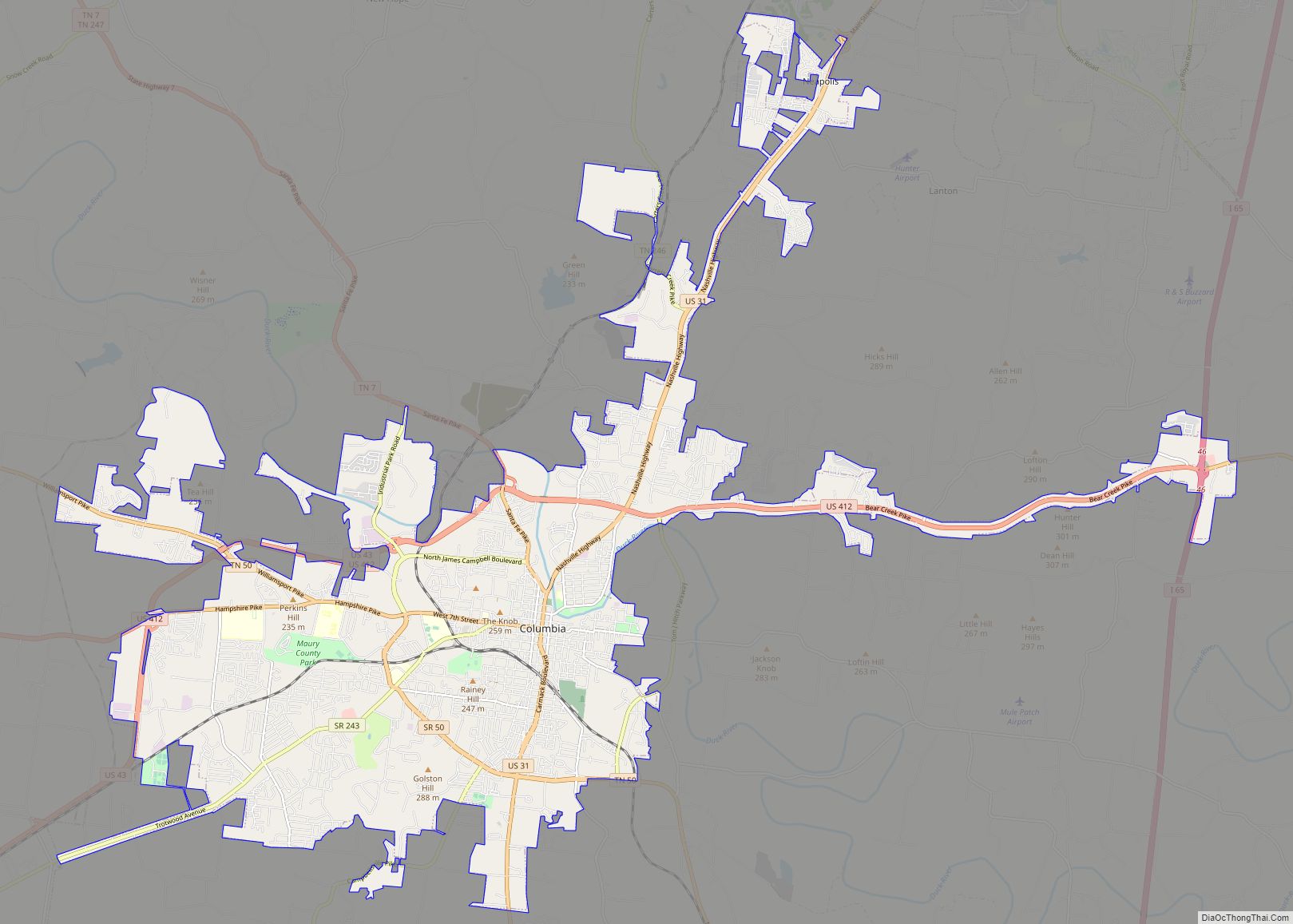

| Seat: | Columbia |

| Total Area: | 616 sq mi (1,600 km²) |

| Land Area: | 613 sq mi (1,590 km²) |

| Total Population: | 100,974 |

| Population Density: | 164.72/sq mi (63.60/km²) |

| Time zone: | UTC−6 (Central) |

| Summer Time Zone (DST): | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Website: | www.maurycounty-tn.gov |

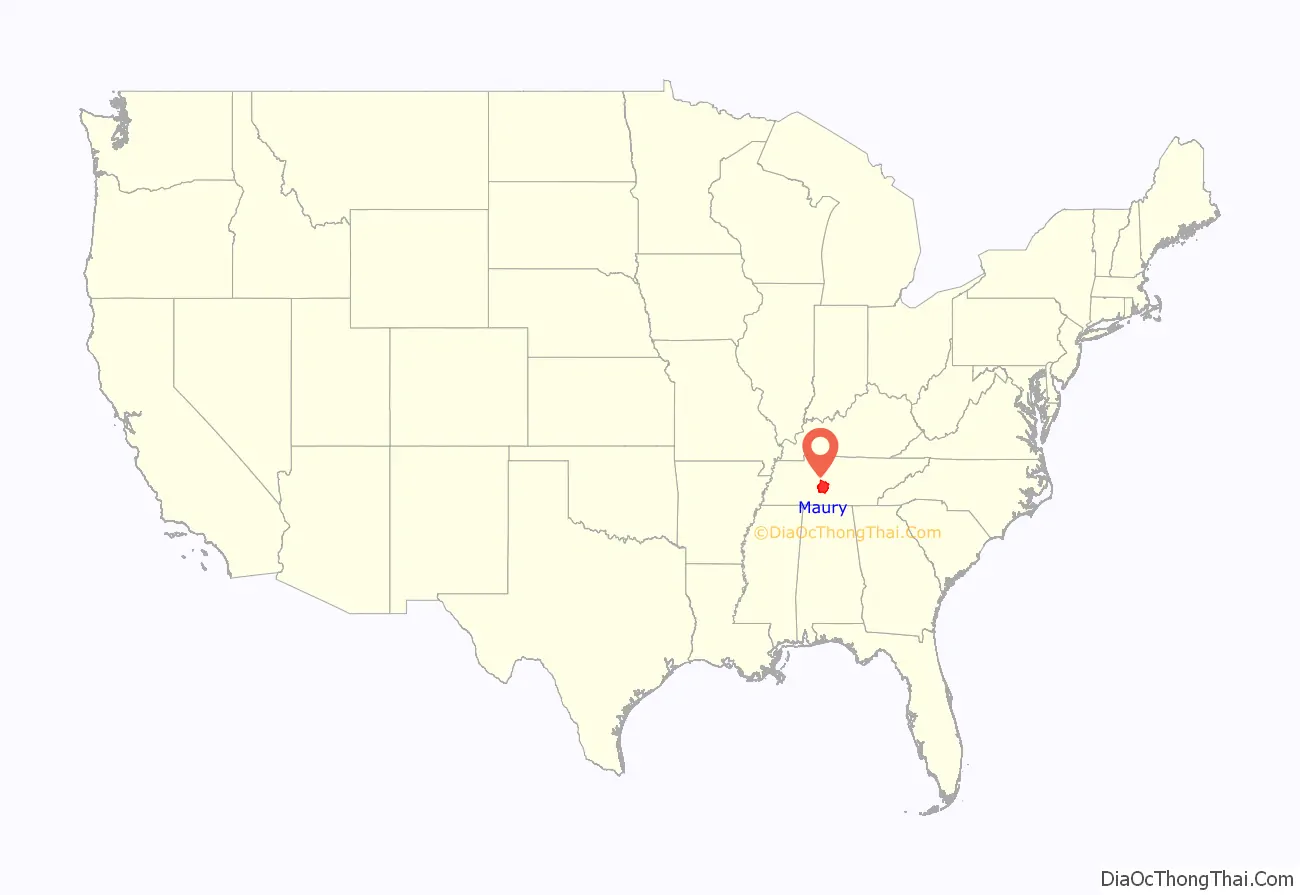

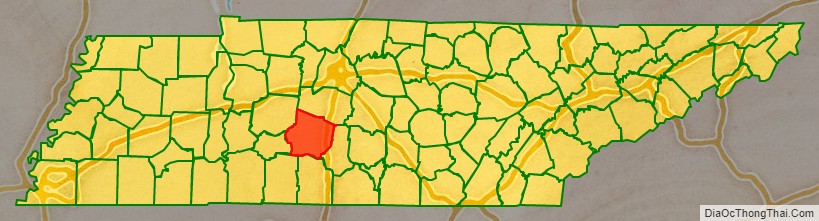

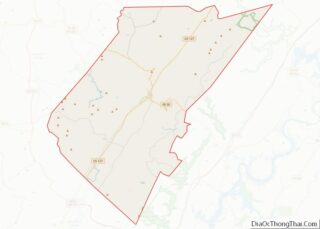

Maury County location map. Where is Maury County?

History

The county was formed in 1807 from Williamson County and Indian lands. Maury County was named in honor of Abram Maury, Sr. (1766-1825), a member of the Tennessee state senate from Williamson County (who was the father of Major Abram Poindexter Maury of Williamson County, later a Congressman; and an uncle of Commodore Matthew Fontaine Maury).

The rich soil of Maury County led to a thriving agricultural sector, starting in the 19th century. The county was part of a 41-county region that became known and legally defined as Middle Tennessee. In the antebellum era, planters in Maury County relied on the labor of enslaved African Americans to raise and process cotton, tobacco, and livestock (especially dairy cattle). Racial violence was less than in some areas, but the county had five documented lynchings in the period from 1877 to 1950, of which three took place in the early 20th century.

With the mechanization of agriculture, particularly from the 1930s, the need for farm labor in the county was reduced. Also, many African Americans moved to northern and midwestern industrial cities in the 20th century to escape Jim Crow conditions and for employment opportunities, particularly during the Great Migration. This movement out of the county continued after World War II. Other changes have led to increased population since the late 20th century, and the county has led the state in beef cattle production.

Columbia Race Riot of 1946

On the night of February 26–27, 1946, a disturbance known as the “Columbia Race Riot” took place in Columbia, the county seat. The national press called it the first “major racial confrontation” after the Second World War. It marked a new spirit of resistance by African-American veterans and others following their participation in World War II, which they believed had earned them their full rights as citizens, despite Jim Crow laws.

James Stephenson, an African-American Navy veteran, was with his mother at a store, where she learned that a radio she had left for repair had been sold. When she complained, the white repair apprentice, Billy Fleming, struck her. Stephenson had been a welterweight on the Navy boxing team and retaliated by hitting Fleming, who broke a window. Both Stephenson and his mother were arrested, and Fleming’s father convinced the sheriff to charge them with attempted murder. When whites learned that Fleming had gone to a hospital for treatment, a mob gathered. There was risk that the Stephensons would be lynched.

Julius Blair, a 76-year-old black store owner, arranged to have the Stephensons released to his custody. He drove them out of town for their protection. When the mob did not disperse, about one hundred African-American men began to patrol their neighborhood, located south of the courthouse square, determined to resist. Four police officers were shot and wounded when they entered “Mink Slide”, the name given to the African-American business district, also known as “The Bottom”. Following the attack on the police, the city government requested state troopers, who were sent and soon outnumbered the black patrollers. The state troopers began ransacking black businesses and rounding up African Americans. They cut phone service to Mink Slide, but the owner of a funeral home managed to call Nashville and ask for help from the NAACP. The county jail was soon overcrowded with black “suspects.” Police questioned them for days without counsel. Two black men were killed and one wounded, allegedly while “trying to escape” during a transfer. About 25 black men were eventually charged with rioting and attempted murder.

The NAACP sent Thurgood Marshall as the lead attorney to defend Stephenson and the other defendants. He gained a change of venue, but only to another small town, where trials took place throughout the summer of 1946. Marshall was assisted by two local attorneys, Zephaniah Alexander Looby, originally from the British West Indies, and Maurice Weaver, a white activist from Nashville. Marshall was also preparing litigation for education and voting rights cases.

Marshall gained acquittals for 23 of the black defendants, even with an all-white jury. At the last murder trials in November 1946, Marshall won also acquittal for Rooster Bill Pillow, and a reduction in the sentence of Papa Kennedy, allowing him to go free on bail.

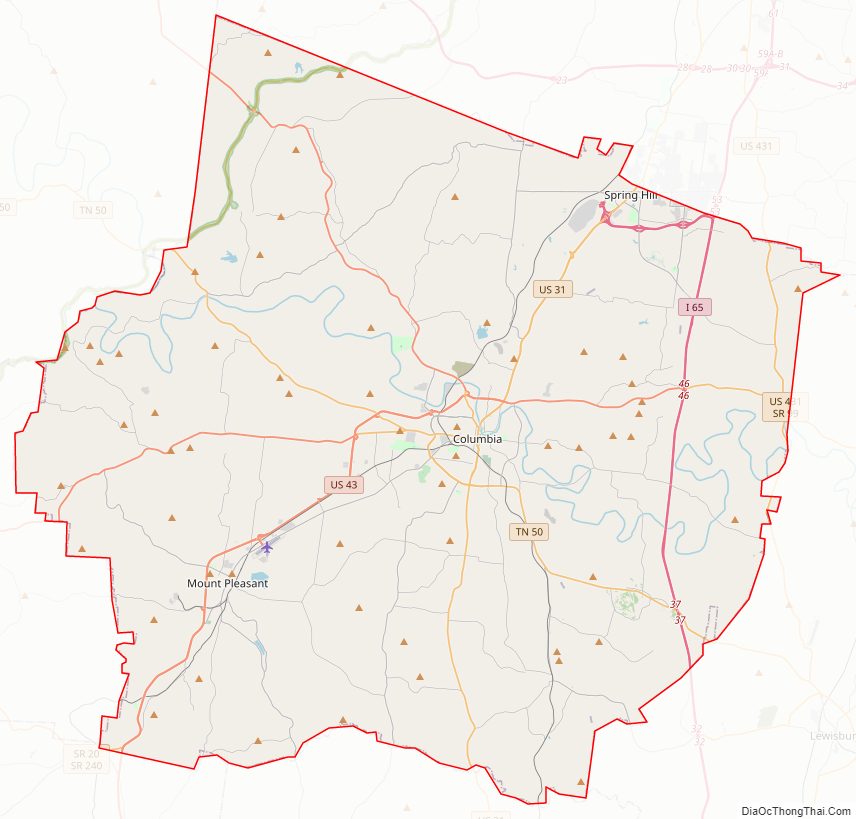

Maury County Road Map

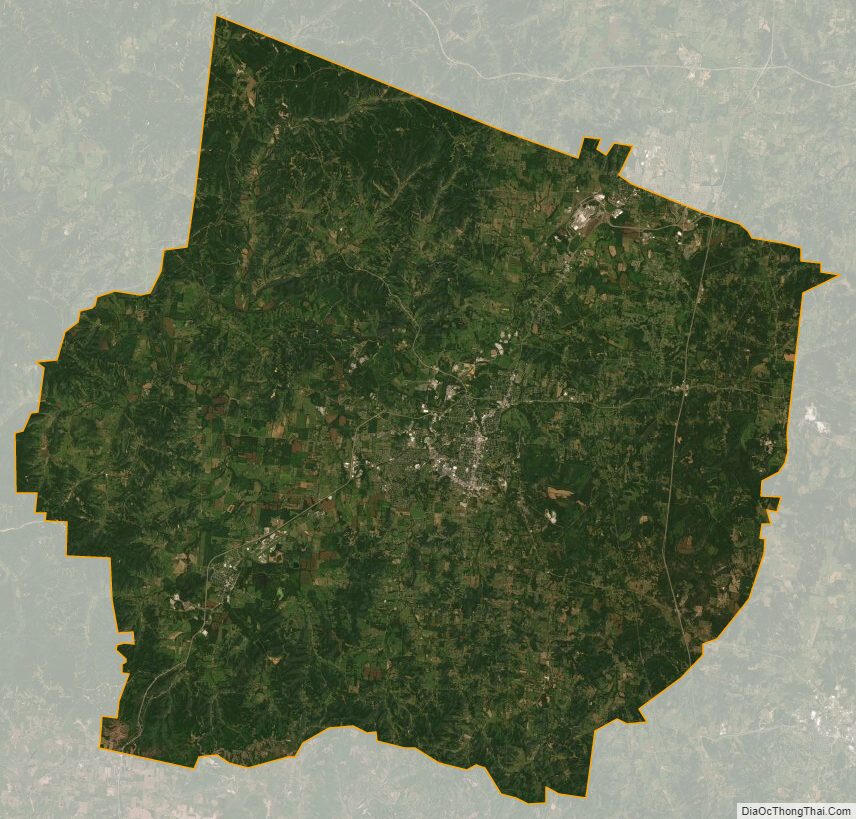

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 616 square miles (1,600 km), of which 613 square miles (1,590 km) is land and 2.4 square miles (6.2 km) (0.4%) is water.

Adjacent counties

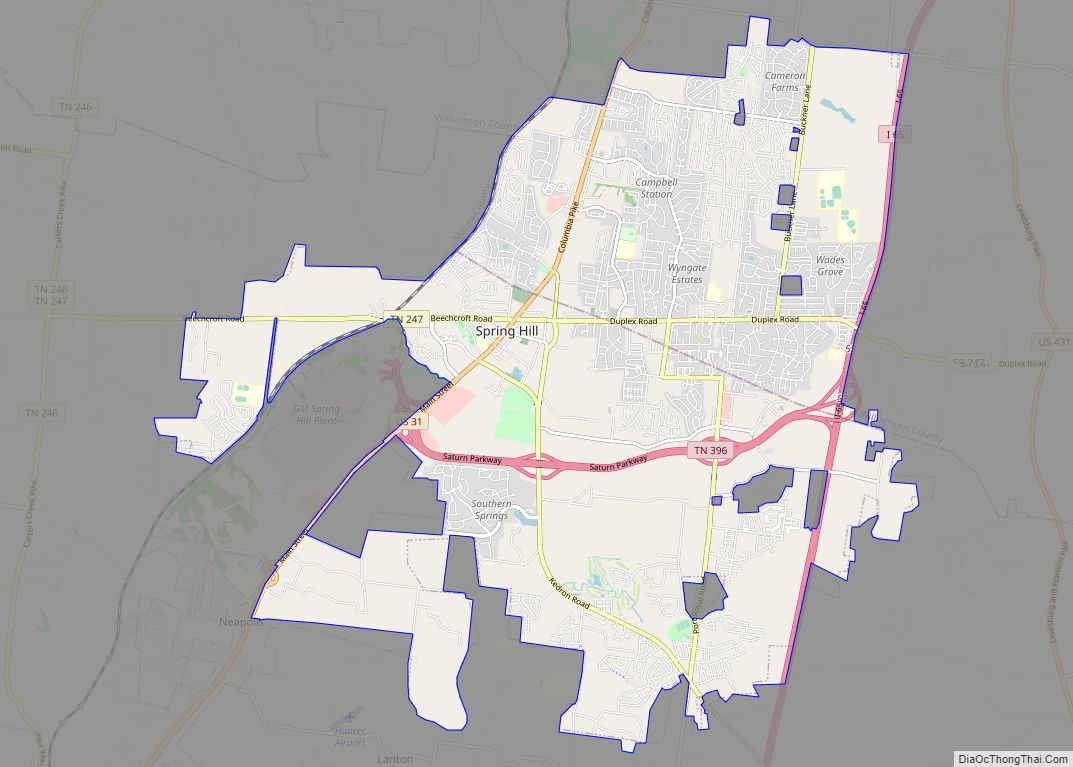

- Williamson County (north)

- Marshall County (east)

- Giles County (south)

- Lawrence County (southwest)

- Lewis County (west)

- Hickman County (northwest)

National protected area

- Natchez Trace Parkway (part)

State protected areas

- Duck River Complex State Natural Area

- James K. Polk Home (state historic site)

- Stillhouse Hollow Falls State Natural Area

- Williamsport Wildlife Management Area

- Yanahli Wildlife Management Area