Columbia is a city in and the county seat of Maury County, Tennessee. The population was 41,690 as of the 2020 United States census. Columbia is included in the Nashville metropolitan area.

The self-proclaimed “mule capital of the world,” Columbia celebrates the city-designated Mule Day each April. Columbia and Maury County are acknowledged as the “Antebellum Homes Capital of Tennessee”; the county has more antebellum houses than any other county in the state. The city is home to one of the last two surviving residences of James Knox Polk, the 11th President of the United States; the other is the White House.

| Name: | Columbia city |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 25 |

| LSAD Description: | city (suffix) |

| State: | Tennessee |

| County: | Maury County |

| Elevation: | 643 ft (196 m) |

| Total Area: | 33.79 sq mi (87.52 km²) |

| Land Area: | 33.77 sq mi (87.45 km²) |

| Water Area: | 0.03 sq mi (0.07 km²) |

| Total Population: | 41,690 |

| Population Density: | 1,234.71/sq mi (476.72/km²) |

| Area code: | 931 |

| FIPS code: | 4716540 |

| GNISfeature ID: | 1269483 |

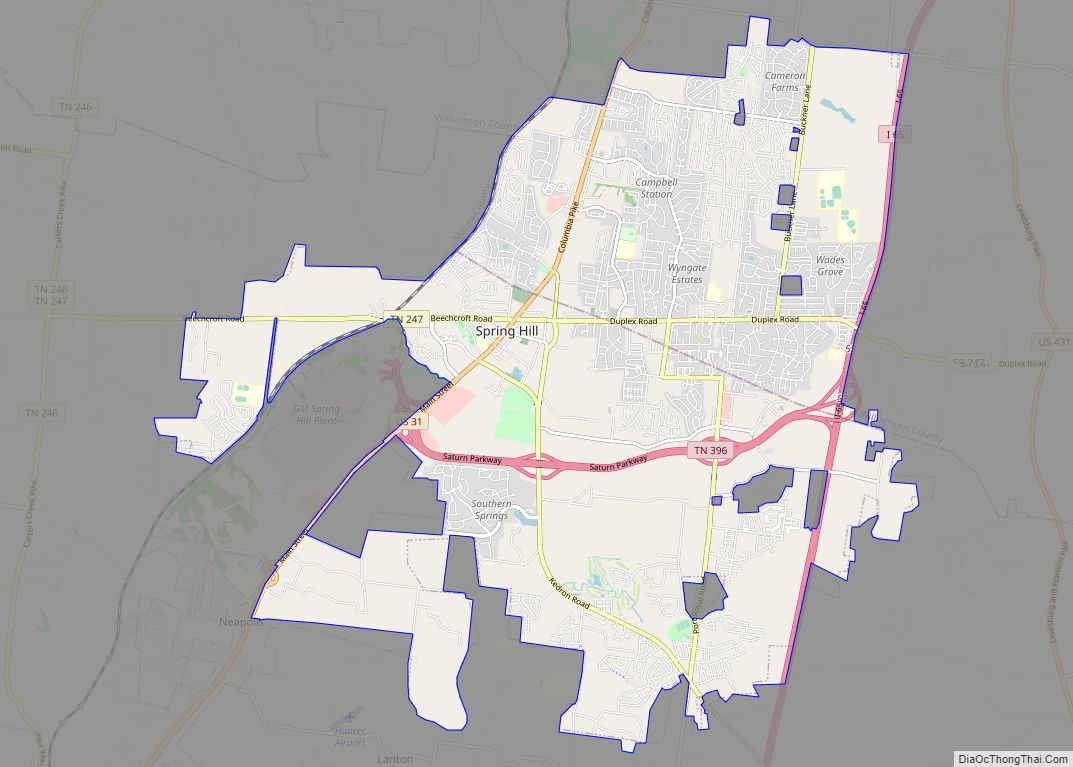

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

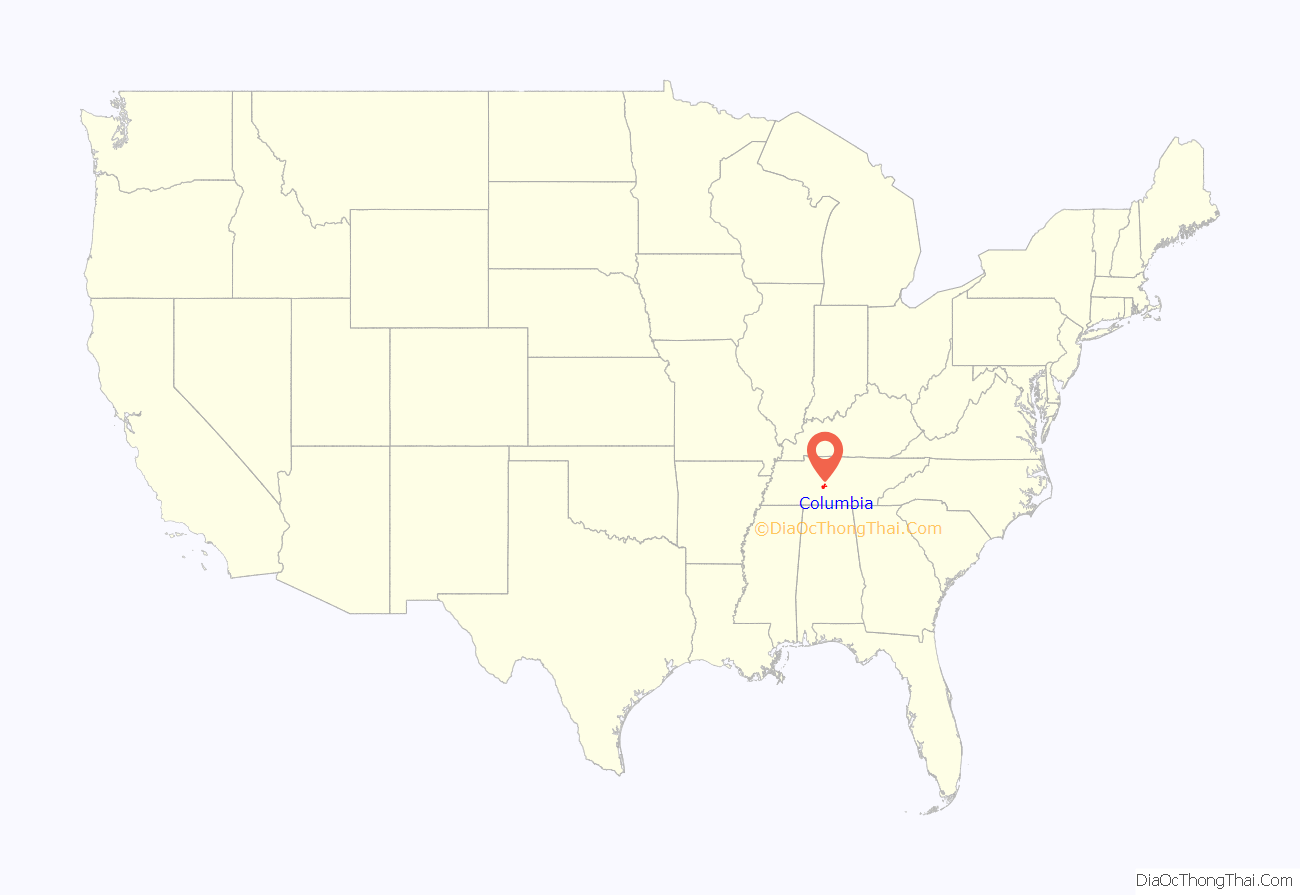

Columbia location map. Where is Columbia city?

History

A year after the organization of Maury County in 1807, Columbia was laid out in 1808 and lots were sold. The original town, on the south bank of the Duck River, consisted of four blocks. The town was incorporated in 1817.

Columbia was the site of Jackson College from 1837 until its destruction by Union troops during the American Civil War.

Columbia had five documented lynchings in the 20th century. In 1924 a Black man was shot and killed in the courthouse after his sentence was commuted, by the brother of his victim. In 1927 and 1933, young Black men were lynched in Maury County for alleged assaults against white women; the first, Henry Choate, was being held as a suspect when he was lynched, and was hanged from the courthouse. In 1933 Cordie Cheek, a 19-year-old Black man, was falsely accused of raping a white girl. After a grand jury declined to indict him, he was abducted from Nashville by white men including law officials, and taken back to Columbia. There he was castrated and lynched by a white mob.

During World War II phosphate mining and the chemical industry expanded in Columbia to support the war effort. By the 1940 census, the total city population was 10,579; more than 3,000 were African American. After the war, chemical plants were a site of labor unrest between white and Black workers, both in terms of competition for work and efforts to unionize. Veterans sought to re-enter the economy, and Black veterans resisted being pushed back into second-class status after having fought in the war. In the postwar period, Black veterans often became leaders in the growing campaign for civil rights during the 1950s and 1960s throughout the state.

Today, the county is a heritage tourism destination, because of its numerous historic sites. Attractions include the President James K. Polk Home, the Columbia Athenaeum, Mule Day, and nearby plantation homes.

For instance, Clifton Place is a historic plantation mansion located southwest of the city on Mt. Pleasant Pike (Columbia highway). Master builder Nathan Vaught started construction in 1838, and the mansion and other buildings were completed in 1839, for Gideon Johnson Pillow (1806-1877) on land inherited from Gideon Pillow.

Columbia is the location of Tennessee’s first two-year college, Columbia State Community College, established in 1966. President Lyndon B. Johnson and his wife Lady Bird Johnson dedicated the new campus on March 15, 1967. On this visit, the President also visited the James K. Polk Home for a short time.

On June 26, 1977, 42 people, including 34 inmates, died in a fire at the Maury County Jail. Rescue efforts were complicated by the fact that each cell required a separate key, and the dispatcher reportedly had difficulty locating the keys. The fire was reportedly intentionally started by a juvenile inmate.

Columbia race riot of 1946

On February 25, 1946, a civil disturbance, dubbed “the Columbia Race Riot,” broke out in the county seat. It was covered by the national press as the first “major racial confrontation” following World War II.

In a fight instigated by William “Billy” Fleming, a white repair apprentice, James Stephenson, a black Navy veteran, fought back and wounded him. Stephenson had been on the boxing team and refused to accept being hit. Stephenson had accompanied his mother to the repair store, which had mistakenly sold a radio which she had left for repair to John Calhoun Fleming, Billy’s father. A white mob gathered during the altercation. The senior Fleming convinced the sheriff to charge both Stephensons with attempted murder.

Rumors were rife that the Stephensons would be lynched. As whites gathered in the square talking about the incident, blacks armed themselves and planned to defend their business district, which they referred to as “the Bottom”. It started about one block south of the square. Later that evening whites drove around the area, shooting randomly into it; they referred to the neighborhood as “Mink Slide.” Armed black men turned out some street lights and shot out others, patrolling the area for defense. Four policemen who entered the area were wounded and retreated, increasing white rage.

Worried that the small police force could not control the mob, the mayor called in the State Guard and the sheriff called in the state Highway Patrol that night. The Guard resisted Patrol requests to arm the white mob. In an uncoordinated effort, the Highway Patrol entered the district early the next morning before a planned time; they provoked more violence and destroyed numerous businesses. Eventually through the next day, they and the State Guard rounded up more than 100 blacks as suspects in the police shootings. No whites were charged at that point. Two black men were killed and a third wounded, in what the police said was an escape attempt while the Highway Patrol was trying to take them from the jail to the sheriff’s office. The State Guard was withdrawn on March 3.

Twenty-five black men were eventually charged with attempted murder of the four policemen. Another six were charged with lesser crimes, as were four white men. The main attorney defending Stephenson and other men in the case was Thurgood Marshall of the NAACP. He worked with Z. Alexander Looby, who was based in Nashville but associated with the national legal team, and Maurice Weaver, a white civil rights lawyer from Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Marshall asked for a change of venue, hoping to get the trial moved to Nashville or another major city. The judge agreed to move the trial only to nearby Lawrenceburg, Tennessee. Local residents there were unhappy to be involved in the controversial case. Marshall and his team achieved acquittal from an all-white jury for all but two men. The prosecution dropped their charges against these men, as they believed the convictions would be overturned on appeal. The Stephensons were never tried, nor were four Whites charged with murder, nor were several blacks. Of two black men tried for murder, only Loyd Kennedy was convicted in his trial of 1947.

The NAACP continued a publicity campaign about these events, which were also covered by national media. The case gained much attention on the issue of civil rights for African Americans in the United States. The NAACP and other organizations put pressure on President Harry S. Truman to take action to improve the situation. He appointed a President’s Committee on Civil Rights, which issued its report in October 1947. In 1948 Truman directed integration of the Armed Services by Executive Order 9981, as a result of the report and his consultation with black leaders. Marshall was later appointed as the first black United States Supreme Court justice.

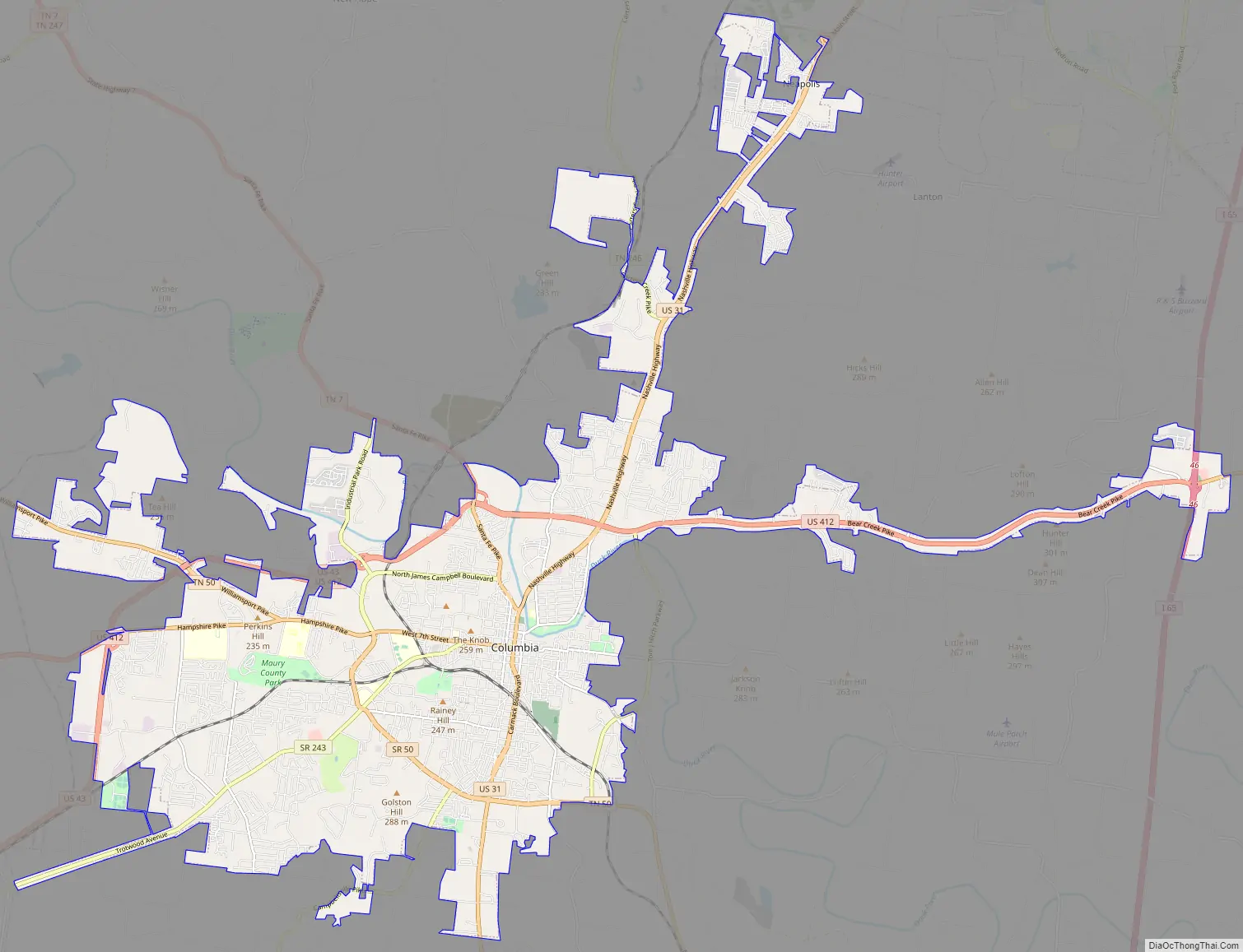

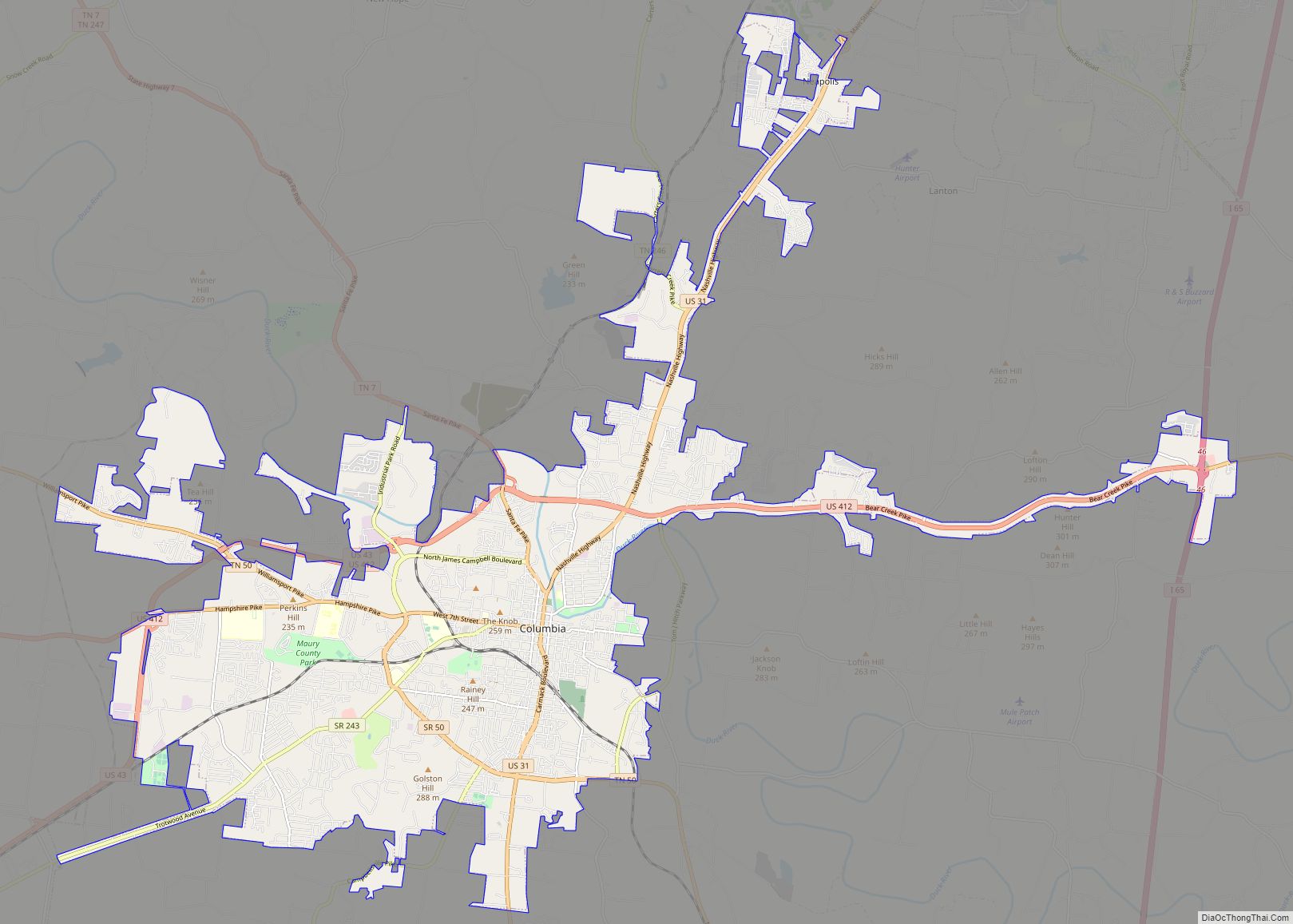

Columbia Road Map

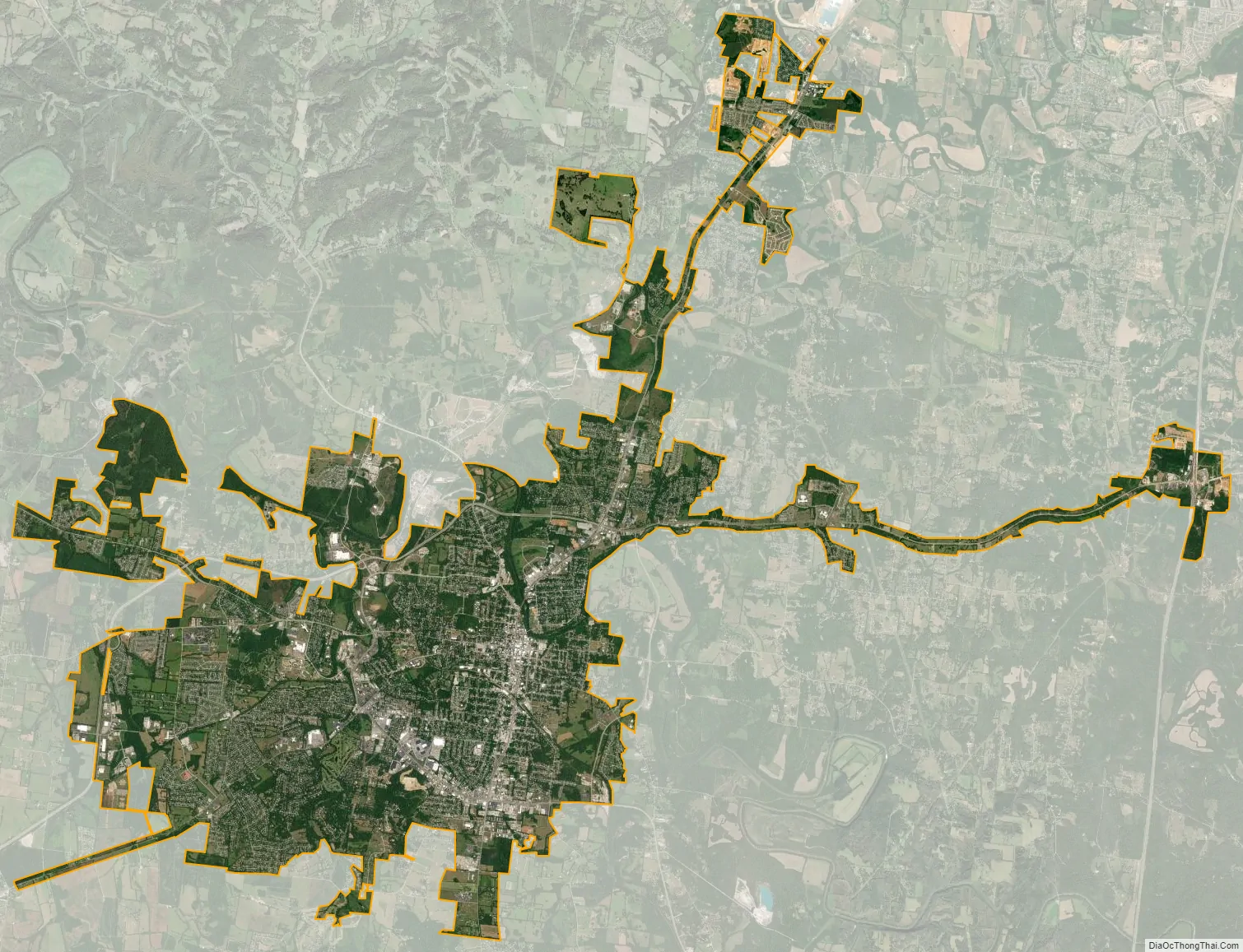

Columbia city Satellite Map

Geography

Columbia is located at 35°36′54″N 87°2′40″W / 35.61500°N 87.04444°W / 35.61500; -87.04444 (35.615022, −87.044464). It developed along the banks of the Duck River at the southern edge of the Nashville Basin; the higher elevated ridges of the Highland Rim are located to the south and west of the city.

The Duck River is the longest river located entirely within the state of Tennessee. Free flowing for most of its length, the Duck River is home to over 50 species of freshwater mussels and 151 species of fish, making it the most biologically diverse river in North America. It enters the city of Manchester and meets its confluence with a major tributary, The Little Duck River, at Old Stone Fort State Park. The fort was named after an ancient Native American structure, between the two rivers, believed to be nearly 2,000 years old. The Duck River is sacred to most of the founding Native American tribes east of the Mississippi River.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 29.6 square miles (77 km), of which 29.6 square miles (77 km) is land and 0.03% is water. Incorporated in 1817, the city is at an elevation of 637 feet (194 m).

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Columbia has a humid subtropical climate.

See also

Map of Tennessee State and its subdivision:- Anderson

- Bedford

- Benton

- Bledsoe

- Blount

- Bradley

- Campbell

- Cannon

- Carroll

- Carter

- Cheatham

- Chester

- Claiborne

- Clay

- Cocke

- Coffee

- Crockett

- Cumberland

- Davidson

- Decatur

- DeKalb

- Dickson

- Dyer

- Fayette

- Fentress

- Franklin

- Gibson

- Giles

- Grainger

- Greene

- Grundy

- Hamblen

- Hamilton

- Hancock

- Hardeman

- Hardin

- Hawkins

- Haywood

- Henderson

- Henry

- Hickman

- Houston

- Humphreys

- Jackson

- Jefferson

- Johnson

- Knox

- Lake

- Lauderdale

- Lawrence

- Lewis

- Lincoln

- Loudon

- Macon

- Madison

- Marion

- Marshall

- Maury

- McMinn

- McNairy

- Meigs

- Monroe

- Montgomery

- Moore

- Morgan

- Obion

- Overton

- Perry

- Pickett

- Polk

- Putnam

- Rhea

- Roane

- Robertson

- Rutherford

- Scott

- Sequatchie

- Sevier

- Shelby

- Smith

- Stewart

- Sullivan

- Sumner

- Tipton

- Trousdale

- Unicoi

- Union

- Van Buren

- Warren

- Washington

- Wayne

- Weakley

- White

- Williamson

- Wilson

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming