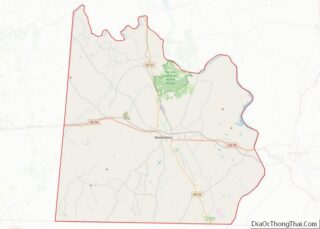

Robeson County is a county in the southern part of the U.S. state of North Carolina and is its largest county by land area. Its county seat is and largest city is Lumberton. The county was formed in 1787 from part of Bladen County and named in honor of Thomas Robeson, a colonel who had led Patriot forces in the area during the Revolutionary War. As of the 2020 census, the county’s population was 116,530. It is a majority-minority county; its residents are approximately 38 percent Native American, 22 percent white, 22 percent black, and 10 percent Hispanic. It is included in the Fayetteville–Lumberton–Laurinburg, NC Combined Statistical Area. The state-recognized Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina is headquartered in Pembroke.

The area eventually comprising Robeson was originally inhabited by Native Americans, though little is known about them. By the mid-1700s, a Native community had coalesced around the swamps near Lumber River, which bisects the area. Later in the century the other lands were occupied by Scottish, English, and French settlers. The population remained sparse for decades due to the lack of suitable land for farming, and timber and naval stores formed a key part of the early economy. The proliferation of the cotton gin and rising demand for cotton led Robeson County to become one of the state’s major cotton-producing county’s throughout much of the 1800s. The Lowry War was fought between a group of mostly-Native American outlaws and local authorities during the latter stages of the American Civil War and through the Reconstruction era. After Reconstruction ended, a unique system of tripartite racial segregation was instituted in the county to separate whites, blacks, and Native Americans.

In the early 20th century, Robeson developed significant tobacco and textile industries, while many of its swamp lands were drained and roads were paved. From the 1950s to the 1970s, the county experienced tensions over racial desegregation. During the same time period, local agriculture mechanized and the manufacturing industry grew. The new industry was unable to provide stable enough employment to locals and by the 1980s Robeson was heavily afflicted by cocaine trafficking. The narcotics trade fueled violence, social unrest, political tensions, police corruption, and caused the county’s statewide reputation to suffer. The county’s economy was further damaged by major declines in the tobacco and textile industries in the 1990s and early 2000s which have now been supplanted by the supply of fossil fuels, poultry farming, biogas and bio-mass facilities, and logging. Robeson continues to rank low on several statewide socioeconomic indicators.

| Name: | Robeson County |

|---|---|

| FIPS code: | 37-155 |

| State: | North Carolina |

| Founded: | 1787 |

| Named for: | Thomas Robeson |

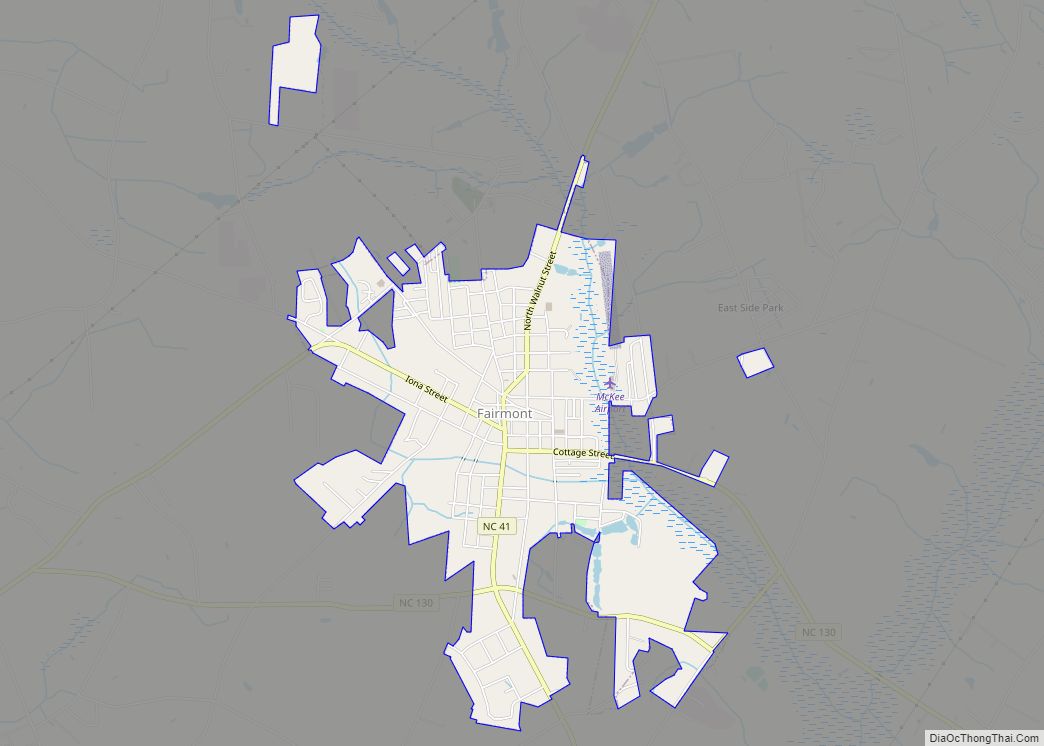

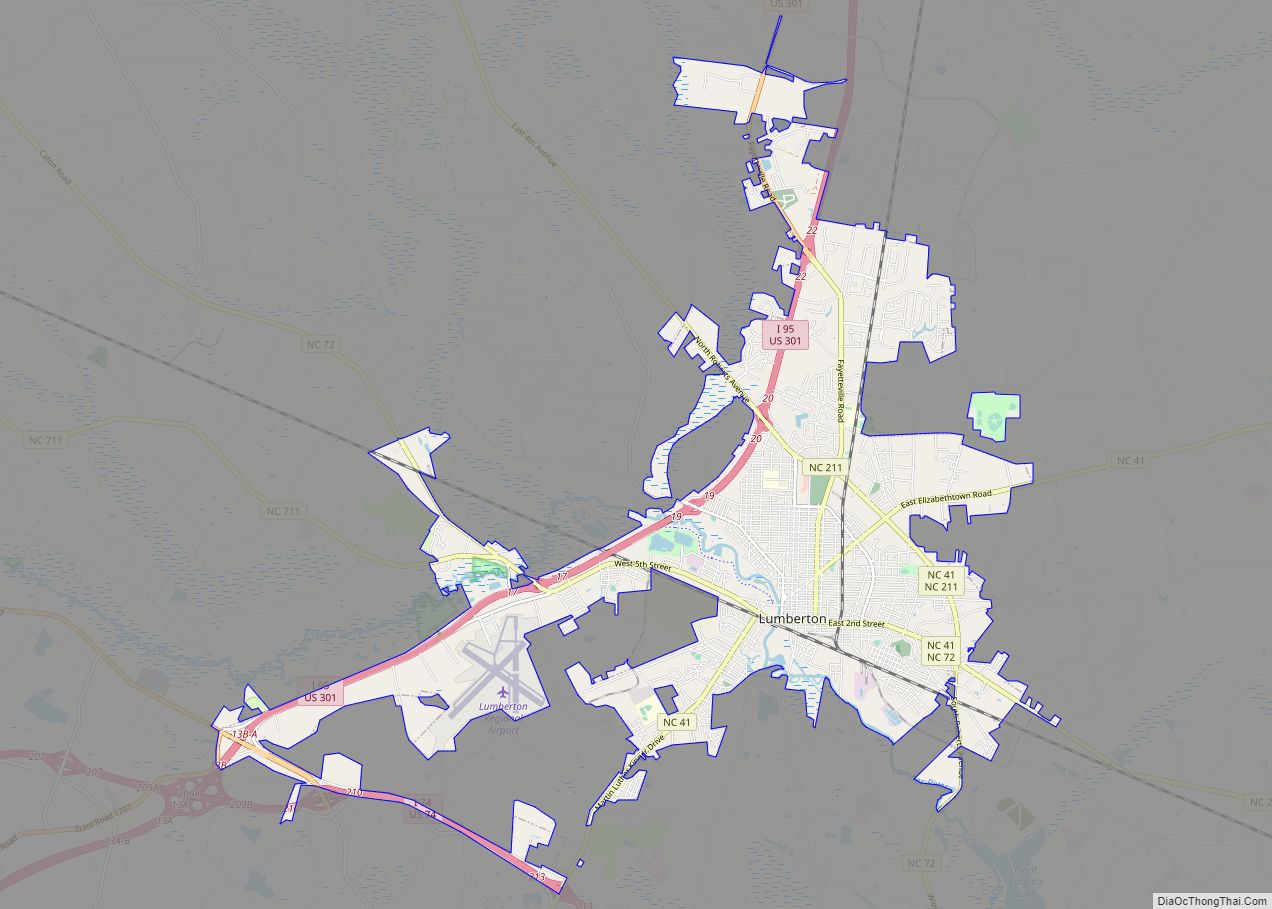

| Seat: | Lumberton |

| Largest city: | Lumberton |

| Total Area: | 951 sq mi (2,460 km²) |

| Land Area: | 949 sq mi (2,460 km²) |

| Total Population: | 116,530 |

| Population Density: | 122.8/sq mi (47.4/km²) |

| Time zone: | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| Summer Time Zone (DST): | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Website: | www.co.robeson.nc.us |

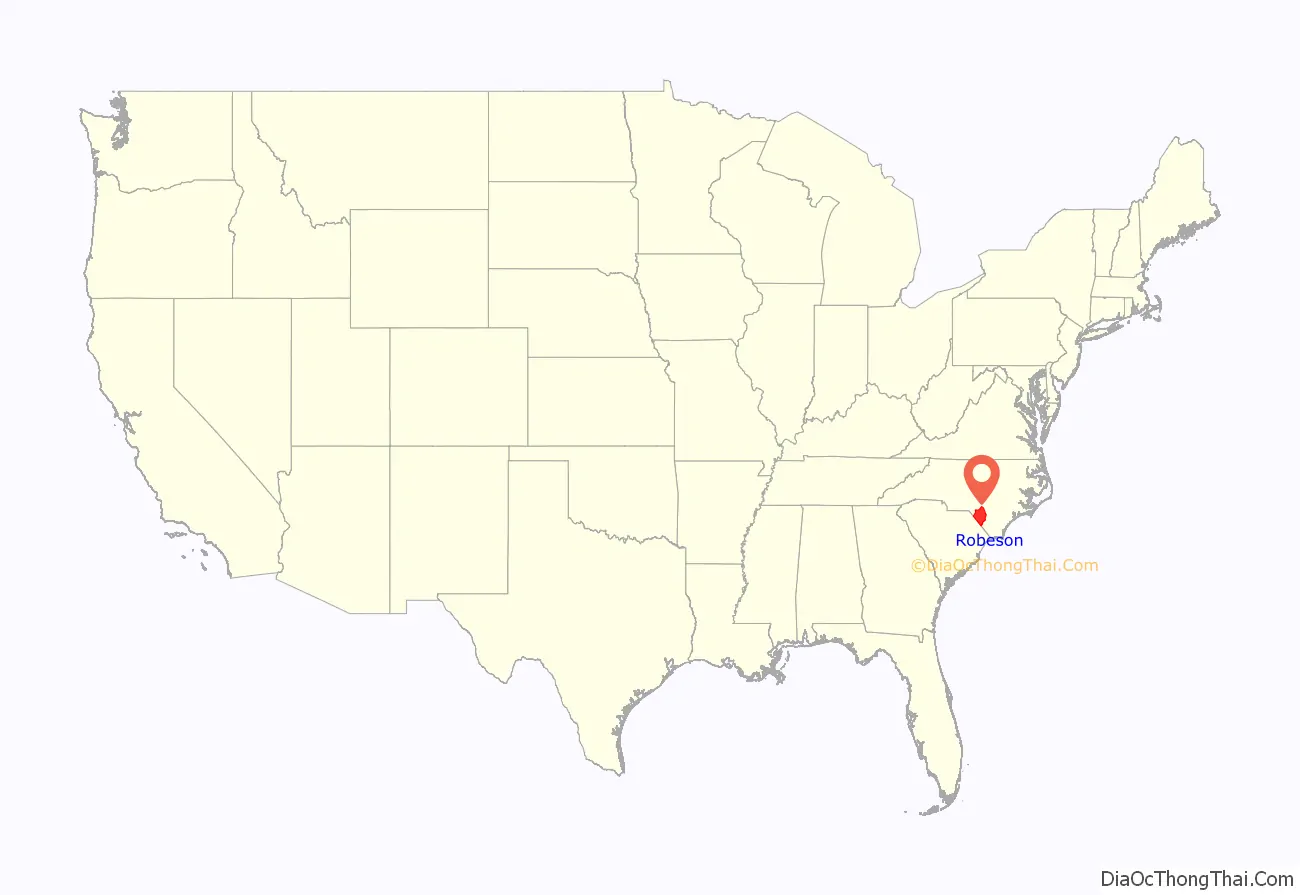

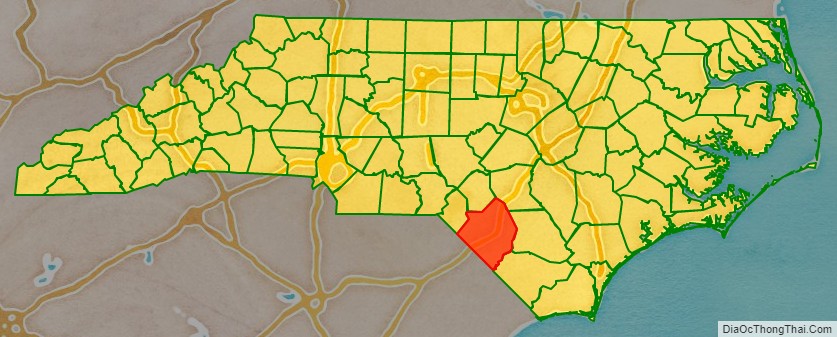

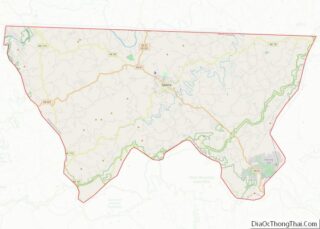

Robeson County location map. Where is Robeson County?

History

Early history and colonial era

Indigenous people have lived in the region as early as 20,000 B.C.E, though little is known about those who lived there in the pre-colonial and early colonial eras. Archeological excavations in the area eventually encompassing Robeson County have uncovered glass beads—often used by Native Americans in trade, pottery, and clay pipes. Archeologist Stanley Knick concluded that the land that had been inhabited continuously from 12,000 B.C.E. in the early Paleo-Indian period through the Archaic and Woodland periods and up to the present. The earliest written mention of Native Americans in the area is a 1725 map compiled by John Herbert, which identified four Siouan-speaking communities near Drowning Creek—later known as the Lumber River.

The Native American/American Indian-descent people in the Lumber River valley eventually coalesced into a series of farming communities collectively dubbed “Scuffletown” by whites but known by its own inhabitants as “the Settlement”. The date of Scuffletown’s formation is unknown as was its actual location. Some scholars believe it was in the vicinity of the later town of Pembroke while others place it at Moss Neck. Historians Adolph Dial and David K. Eliades believed that it was a mobile community. Others still believe the name applied broadly to any concentration of Indians in the area. Culturally, the Scuffletonians were similar to other Europeans in their dress and style of homes. They were Protestant Christians and spoke English, though they spoke an “older form” which set them apart from later settlers. Not viewed as Native Americans by the state of North Carolina until the 1880s, these people were generally dubbed “mulattos” by locals and in federal documents throughout the mid-1800s to distinguish them from blacks. The original Scuffletonians were joined by some whites and blacks in the mid-1700s, including some escaped slaves. The earliest written record of white settlement dates from 1747 land deed applications.

The area eventually comprising Robeson County was not heavily settled by whites until about 10 years before the American Revolution, when Highland Scots moved into the area. They formed a separate community from the Scuffletonians. The immigrants encompassed a range of class distinctions, from literate and aristocratic English-speaking families to poorer Scottish Gaelic-speakers, many of whom were indentured servants. The latter were called “Buckskins” due to their reputation for wearing pants made of deer leather. Gaelic remained spoken in the area as late as the 1860s. English and a few French settlers moved into the eastern portion of the eventual county. Despite the increase in settlement, population levels in the Lumber River valley remained low for many years, as swamps and thick vegetation divided arable land and made transportation difficult. The production of timber and naval stores formed a key part of the area’s early economy, with logs being floated down the river for sale in Georgetown, South Carolina in the late 1700s. During the American Revolutionary War, control over the Lumber River valley was heavily contested by British Loyalists and Patriots. Tensions raised by the war caused some whites to migrate out of the area, moving as far away as Canada.

Creation

Robeson County was created by the North Carolina General Assembly in 1787 out of a western section of Bladen County. It was named for Thomas Robeson, a colonel who had led Patriot forces in the area during the Revolutionary War. General John Willis, owner of the Red Banks plantation, lobbied to have the county’s new seat of government located on his land. The site, to be known as Lumberton, was chosen due to its central location in the county, proximity to a reliable ford of the Lumber River, and as it was where several roads intersected. The first county courthouse was a wooden residence sold by Willis and moved into place after land was cleared. Lumberton served as county residents’ primary area of commerce for much of the area’s early history, as transportation links with major regional cities elsewhere were tenuous. The 1790 United States census recorded 5,356 county residents. The county’s first U.S. Post Office was established there by 1796. That year settlers moved up the Lumber River and established Robeson’s second community, Princess Anne. Much of the county’s geography was not officially understood by surveyors until the early 1800s. The county’s boundaries were modified and remarked several times between 1788 and 1832.

Antebellum

Initially, wheat, corn, rice, sugar cane, and potatoes were popular crops among Robesonian farmers. The proliferation of the cotton gin and rising demand for cotton led it to be rapidly adopted, and Robeson County became one of the state’s major cotton-producing county’s throughout much of the 1800s. Wealthy white planters held the best land in the county, and often outcompeted smallholding Indian and white farmers due to the aid of slave labor, creating stark class divisions. Cotton demand facilitated the growth of slavery and the expansion of plantations. By 1850, the county had a population of 7,290 whites, 4,365 slaves, and 1,171 free persons of color.

In 1835 a new Constitution of North Carolina was ratified, which restricted the ability of “free persons of color” and “free persons of mixed blood” to vote and bear arms. While having previously enjoyed the same political rights as white people, the Indians were disenfranchised by the new constitution. White farmers in Robeson County also sought ways to obtain Indians’ land or labor. According to Indian oral tradition, the “tied mule” incidents were emblematic of this. In these scenarios, a farmer would tie his mule on an Indian’s land and release some of his cattle there, before bringing local authorities to the scene to accuse the Indian landowner of theft. Doubtful of a fair trial in the courts, an Indian would settle with the farmer by either offering him a portion of land or free labor. By the 1860s, many Indians were landless. The legal discrimination and exploitative practices heightened racial tensions in the area.

In 1848 a new county courthouse was constructed to replace the original building. Lumberton was formally incorporated four years later. In 1860, the Wilmington, Charlotte and Rutherford Railroad was laid through the county as its first railway. By April 1861, the line reached the town of Shoe Heel—later known as Maxton. The introduction of the railroad facilitated the creation of new towns in the county.

Civil War

North Carolina seceded from the United States in 1861 and joined the Confederate States of America to fight in the American Civil War. Many Indians and Buckskin whites were unenthusiastic about the war; most local supporters of the Confederate cause were wealthy or well-educated. Some Indian men enlisted in the Confederate States Army, though it unknown whether they were accepted as recognized Indians or passed as white. Major white slaveholders were exempted from service, as were those wealthy enough to pay for surrogates to serve in their place. In 1863, Confederate authorities began conscripting the Indians and other free persons of color for labor along the coast, especially at Fort Fisher. The Indians were usually tasked to either construct batteries or grind salt. Most found the work dangerous and monotonous, and the conditions at the labor camps poor. Many consequently fled into the swamps of Robeson County to avoid conscription. Though some Indians still sought to serve in the army during this time, by late 1863 most had concluded that the Confederacy was an oppressive regime. This change in attitudes was brought on by their contact with Union prisoner-of-war escapees from the Florence Stockade, 60 miles (97 km) away in South Carolina. Indians became increasingly willing to help the Union soldiers escape and avoid recapture.

As time progressed some of the swamp deserters—including Indians, blacks, and Union soldiers—formed bands to raid and steal from area farms, though this was mostly out of a desire to survive and had little to do with challenging the Confederacy. The Indians’ aid to the Union escapees and their attempts to dodge labor conscription drew the attention of the Confederate Home Guard, a paramilitary force tasked with maintaining law and order in the South during the war. In early March 1965, Union troops led by General William Tecumseh Sherman entered North Carolina. The Union escapees left to join them, and the bands became predominantly Indian. Union forces entered Lumberton on March 9, burning two bridges and a depot. They also foraged off of the goods of locals, seizing draft animals, cattle, and crops. The bulk of Confederate forces surrendered at Appomattox, Virginia shortly thereafter. On May 15, slaves in Robeson were declared emancipated.

Reconstruction and Lowry War

In 1864, during the latter stages of the Civil War, Confederate postmaster James P. Barnes accused some sons of Allen Lowry, a prominent Indian farmer, of stealing two of his hogs and butchering them to feed Union escapees. He ordered the Lowry family to stay off his land under threat of being shot. In December, Barnes was ambushed and shot as he made his way to work. Shortly before he succumbed to his wounds he accused William and Henry Berry Lowry, two sons of Allen, of committing the attack. The following January, Confederate Home Guard officer James Brantly Harris was ambushed and shot following his involvement in the deaths of three Lowrys. Fearing Harris’ death would lead to retaliation from the Home Guard, local Indians began preparing for violence. Short on food and weapons, they began stealing from white-owned farms and plantations. Supplies intended for the guard was stolen from the courthouse in Lumberton.

White citizens were infuriated by the decline in law and order, and the Home Guard suspected that the Lowry family was largely responsible. On March 3, 1865, a Home Guard detachment arrested Allen Lowry and several others. Following an impromptu tribunal, the guardsmen executed Allen and his son William for allegedly possessing stolen goods. The Home Guard was briefly disrupted by the incursion of Sherman’s troops several days later, but thereafter resumed investigating the Lowry family. These events initiated the Lowry War, a conflict which dominated Robeson County throughout the Reconstruction period.

The situation in Robeson County briefly calmed with the Union victory, as locals focused on rebuilding their livelihoods. The region suffered an economic downturn brought on by an agricultural depression and the destruction of the turpentine industry by Union troops. Some white Robesonians moved down the Lumber River into South Carolina in search of new farmland, while others moved west. Many black freedmen turned to tenant farming. Local government in Robeson mostly continued as it had during the war, with rich white men of prominence dominating public offices, especially the justices of the peace who constituted the county court. The Home Guard was formally dissolved but was replaced by a similar institution, the Police Guard.

In December the Police Guard arrested Henry Berry Lowry at his wedding and held him on charges of murdering Barnes. He shortly thereafter escaped custody and avoided the authorities by hiding in swamps with a group of associates which became known as the Lowry Gang. Although a somewhat fluid band at times numbering 20–30 men, the gang usually operated with six to eight men. The principle members were mostly relatives of Lowry, though the gang also included two blacks and a poor white. They usually stayed in improvised shelters in Back Swamp, a ten-mile long stretch of sparsely-traveled land near Allen Lowry’s homestead. Throughout 1866 and 1867 the gang conducted raids “in retaliation” for previous wrongs inflicted upon them, but no people were killed.

Following the passage of federal Reconstruction Acts in 1867 and the ratification of a new state constitution in North Carolina in 1868, nonwhites in Robeson, both black freedmen and Indians, were re-enfranchised. The Republican Party won a majority of the vote in elections in Robeson, displacing Conservative planter families who had dominated county affairs. The party relied on the electoral support of black freedmen, Indians, and poor Buckskin whites. Republican officials were reluctant to take any action concerning the lawlessness in Robeson, since prosecuting former Home Guardsmen for their extrajudicial killings would harm their law and order campaign, while targeting the Lowry Gang would split their local base of support. Despite this, the new Republican Governor of North Carolina, William Woods Holden issued a declaration of outlawry against Lowry and some of his associates, dividing the local Republican Party and threatening their hold on county politics.

In an attempt to broker a solution, local Republicans convinced Lowry to surrender himself to be tried in the postwar court system, but he shortly thereafter escaped. The Lowry Gang then killed Reuben King, the former sheriff of the county, during a robbery in January 1869, ending all attempts by Reconstruction authorities to negotiate a settlement. The gang continued its raids, and as a result federal troops were dispatched to assist the local authorities. In February 1872, the Lowry Gang committed their largest heist, stealing two safes from downtown Lumberton. Shortly thereafter, Henry Berry Lowry disappeared. Over the next two years bounty hunters tracked down the remaining gang members, and the war ended when the last active one was killed in February 1874.

End of Reconstruction and establishment of racial segregation

Dissatisfied with the 1868 Reconstruction constitution, Conservatives/Democrats pushed for a convention to be held in 1875 to revise the document. Elections to determine the delegates to attend were held in August. Early returns indicated that a Republican-majority convention was likely, and the final results from Robeson County were, depending on the outcome, likely to provide either party with their majority. The state Democratic chairman sent a telegraph to the local Democrat-dominated elections board, writing, “As you love the state, hold Robeson.” The board then voted to certify the elections without counting results from four Republican-majority precincts, giving the county’s two Democratic delegate candidates a slim margin of victory. With their narrow majority at the convention, the Democrats reversed many of the reforms instituted in the 1868 constitution, making it harder for Republicans and blacks to hold office.

With Reconstruction thus ended, Democrats reasserted their dominance over politics in the South, but Republicans remained competitive in North Carolina and the Indian population in Robeson continued to support them. Though Republicans still made up the majority of registered voters in Robeson, disagreements caused by the Lowry War prevented them from solidifying local control. The Indians also resisted being treated the same as blacks under the new socio-political hierarchy, who were relegated to a subordinate position. Hamilton McMillan, a Robesonian member of the North Carolina House of Representatives and a Democrat, sought to switch the Indians’ allegiance to solidify his party’s control over the state. He convinced the General Assembly to formally recognize the Indians as “Croatoans”—arguing that they descended from English settlers of the Lost Colony who mixed with Croatan Indians.

In 1887, McMillan convinced the legislature to appropriate money for the establishment of a Croatan Normal School to train teachers who could staff new Indian schools. As a result, most Robeson Indians began to vote for Democrats, and their voting rights were preserved when blacks were disenfranchised by constitutional amendment in 1900. This distinction birthed a system of tripartite segregation which was unique in the American South, though whites generally regarded both the Indians and blacks as “colored”. Indians and blacks nevertheless maintained separate identities. Some other county facilities were separated for “Whites”, “Negroes”, and “Indians”, including the courthouse in Lumberton. Under this racial hierarchy, whites constituted the dominant racial caste and blacks were socially subordinated, while the Indians formed a middle caste and, though retaining more privileges than blacks, were still subject to discrimination.

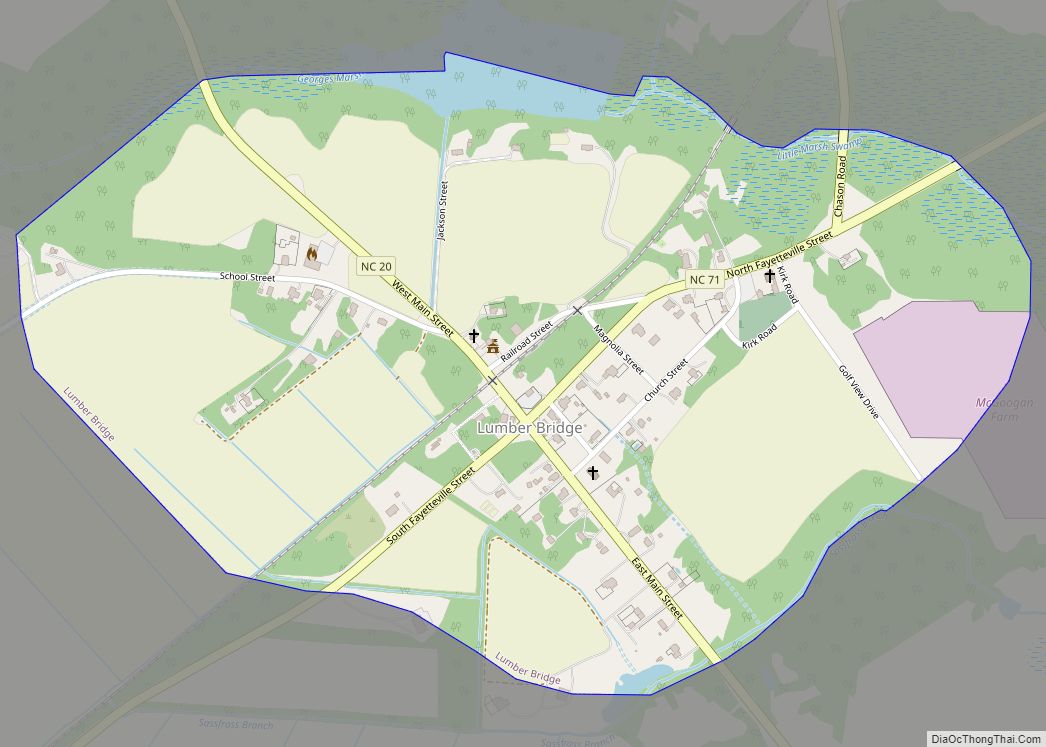

The county’s second rail line was established in 1884 by the Cape Fear and Yadkin Valley Railway, connecting Lumber Bridge, Red Springs, and Maxton. In 1892, the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad built a north-south line through the county, intersecting with the Wilmington, Charlotte and Rutherford Railroad at the site of Campbell’s Mill. A train station was subsequently built and a strong trading community was established. It was incorporated in 1895 as the town of Pembroke and in 1909 the Croatan Normal School was moved there from its original location in Pates. Pembroke became a center for Indian commercial activity. Due to the Indians’ predominance in the community, the town lacked strict adherence to many Jim Crow norms common in rest of the county and the wider South in the early-to-mid 20th century. St. Pauls and Red Springs developed as white-majority towns hostile to nonwhites, while the towns of Fairmont and Rowland retained significant black labor forces. In 1913 the General Assembly reclassified the Indians as Cherokees.

Economic development and Great Depression

Following the stagnation of cotton prices in the 1890s, farmers in Robeson County began rapidly adopting tobacco as a regular crop. Many tobacco warehouses were built, and the town of Fairmont became the county’s primary market town for the crop. Significant tobacco markets were also established in Rowland and Lumberton. The county’s first cotton mill opened in 1897, and St. Pauls subsequently developed as the county’s primary textile center. In the early 1900s area farmers organized a trade association and convinced the county government to appoint a local commissioner for agriculture.

In 1909, Robeson County’s third courthouse was constructed. Two years later a portion of the county was split off and combined with a section of Cumberland County to form Hoke County. Bouts of typhoid, hookworm, smallpox, and a high infant mortality rate led Robeson’s government to organize the first county-level public health department in the United States in 1912. Following the passage of a state drainage law in 1909, many swamps in the county were drained to increase usable farmland, improve transportation, and reduce malaria cases. Work on the drainage of the nearly 22,000-acre Back Swamp was completed in 1918. Most major roads in the county were paved with state support between the 1920s and 1947. In 1929, Robeson became the first county in the United States to appoint a county manager.

Similar to the rest of the country, local agriculture suffered throughout the 1920s following World War I due to decreased demand and limited market opportunities for crops. The Great Depression led to a severe decline in tobacco prices. Area farmers responded by increasing their output, but the expanded agricultural supply only pushed crop prices lower. Robesonians dubbed the time period the “Hoover Days”. In response to the downturn, in 1936, the federal government created Pembroke Farms, a resettlement community for struggling Indian farmers. In 1938, the government offered loans for the establishment of a second project, the Red Banks Mutual Association. The association served as a cooperative with multiple Indian households farming common land from which profits would be attained and then divided among the members. Neither project proved successful, and by the 1940s both were facing neglect from the government, though the mutual association persisted into the 1960s before it finally collapsed.

Civil rights and desegregation

Hundreds of Indians from Robeson County fought for the United States during World War II in white units (blacks were segregated into different outfits). Many returned with a willingness to pursue social change. Some of them, especially the war veterans, disliked Robeson County’s segregation. In 1945 a group of Indians petitioned the governor to support the restoration of an elected municipal government in Pembroke, which had been swapped for an appointive system in 1917 at the behest of the community’s white minority. Two years later, the town returned to an elected government and Pembroke chose its first Indian mayor. Other Indian leaders lobbied for the adoption of a unique name to identify their group. In 1952 the name Lumbee, inspired by the Lumbee/Lumber River, was approved by the Indians in a referendum, and the following year the General Assembly formally recognized the label. In 1956 the United States Congress formally extended partial recognition to the Lumbee Tribe, affirming their existence as an indigenous community but disallowing them from use of federal funds and services available to other Native American groups. Other Indians rejected the Lumbee designation and identified themselves as Tuscarora—stressing a connection to the Tuscarora people who had populated North Carolina in the 1700s—with the aim of securing a better chance at full federal recognition.

In 1954 the United States Supreme Court issued its decision in Brown v. Board of Education, ruling that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. The ruling sparked a significant amount of pro-segregation activity among whites in the South, including a resurgence in white supremacist Ku Klux Klan (KKK) activity. Klan activity and violence increased in Robeson in the early 1950s before being suppressed under pressure from the district solicitor and the federal government. In early 1958, Klan leader James W. “Catfish” Cole of South Carolina attempted to revive the Klan in Robeson County. His group burned crosses in St. Pauls and Lumberton to intimidate the Lumbee community before advertising a rally to be held at Hayes Pond, near Maxton. The rally was held on the evening of January 18, attended by about 50 Klansmen—most not from the county, and joined by several hundred armed Lumbees. The Lumbees opened fire, inflicting minor injuries and causing the Klansmen to disperse. The event, dubbed by the press as the “Battle of Hayes Pond”, garnered national media attention and led Klan activity against the Lumbees to cease.

Pembroke State College (formerly the Croatan Normal School) racially integrated in the 1950s and 1960s. After 1965, the rate of black and Native American voter registration substantially increased. By 1968, black and Native voters outnumbered whites. In 1970 the federal government ordered the county school board to integrate its institutions. The board responded by dissolving special Native American districts and consolidating Native students with black and white schools. This did not affect most white students in the county, who were largely served by independent municipal school districts. Feeling a loss of control over their traditional schools, many Lumbees and Tuscaroras protested integration and resisted the assignment of black staff and white and black students to their institutions.

In early 1973, dozens of buildings in the county, most of them owned by whites, were set ablaze. In March, Old Main, a historic building on Pembroke State’s campus which had symbolic importance to the Native American community, was burned. In 1974, a federal court ruled that the “double voting” system used by the county school board, whereby both county residents and municipal residents could vote for board members—despite the latter not being served by the county school system, was unconstitutional. Following a bitter 1986 referendum which received national attention, the municipal systems were merged with the county system in 1988.

Pembroke State College was elevated to university status in 1971 and was grouped under the University of North Carolina system the following year. In 1974 the county courthouse was demolished. It was replaced with a new structure in 1976.

Drug trafficking and economic stagnation

Robeson County became one of the top moonshine-producing counties in North Carolina in the 20th century. The prevalence of poverty enticed many Robesonians to sell moonshine to supplement their incomes, and the large number of isolated swamps and woods offered many places where stills could be concealed. Many Lumbees and Tuscaroras produced moonshine into the 1970s. The trade of marijuana eventually supplanted moonshine before being overtaken by cocaine trafficking in the 1980s, which was enabled by the county’s midway location between Miami and New York City along Interstate 95. The drug trade was fueled by worsening economic prospects in the region which began with the 1970s energy crisis and increased living costs. By the mid-1980s, local agriculture was in decline; reliance on mechanised agriculture and the consolidation of smallhold