Pushmataha County is a county in the southeastern part of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. As of the 2010 census, the population was 11,572. Its county seat is Antlers.

The county was created at statehood from part of the former territory of the Choctaw Nation, which had its capital at the town of Tuskahoma. Planned by the Five Civilized Tribes as part of a state of Sequoyah, the new Oklahoma state also named the county for Pushmataha, an important Choctaw chief in the American Southeast. He had tried to ensure that his people would not have to cede their lands, but died in Washington, DC during a diplomatic trip in 1824. The Choctaw suffered Indian Removal to Indian Territory.

| Name: | Pushmataha County |

|---|---|

| FIPS code: | 40-127 |

| State: | Oklahoma |

| Founded: | 1907 |

| Named for: | Pushmataha |

| Seat: | Antlers |

| Largest city: | Antlers |

| Total Area: | 1,423 sq mi (3,690 km²) |

| Land Area: | 1,396 sq mi (3,620 km²) |

| Total Population: | 11,572 |

| Population Density: | 8.3/sq mi (3.2/km²) |

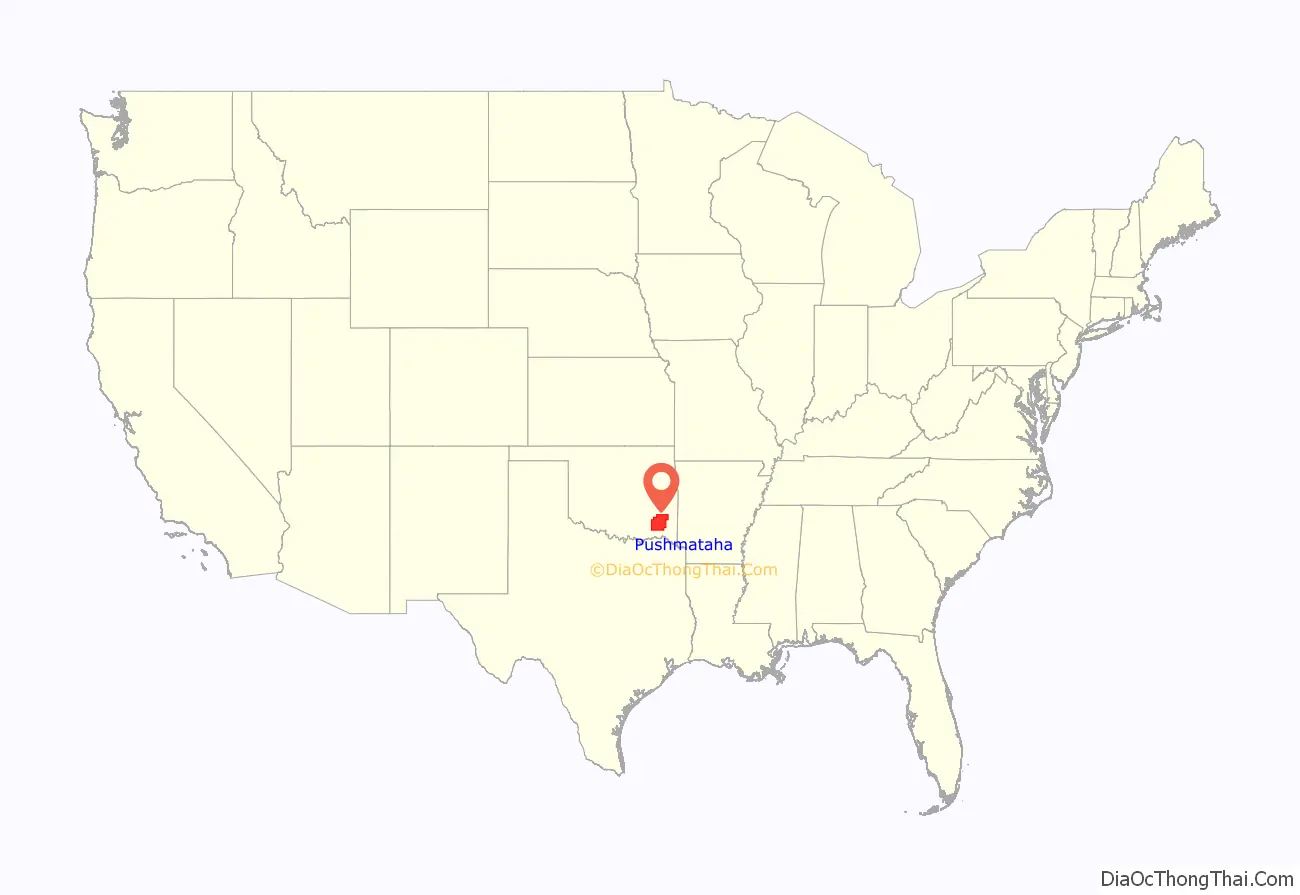

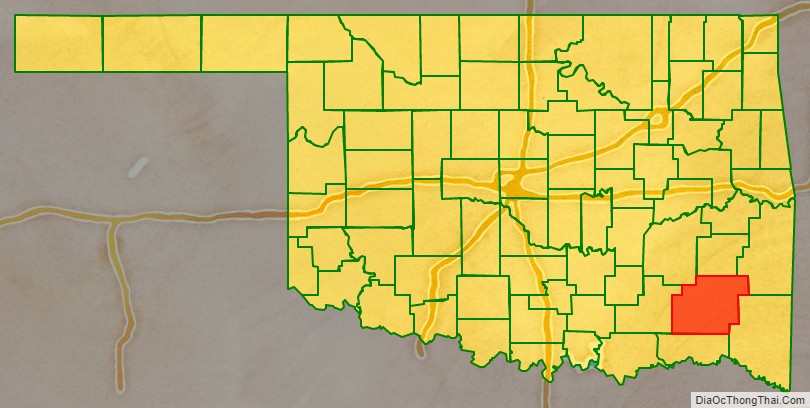

Pushmataha County location map. Where is Pushmataha County?

History

Administrative history

- Ca. 1000–1500: Caddoan Mississippian culture at Spiro Mounds

- 1492–1718: Spain

- 1718–1763: France

- 1763–1800: Spain

- 1800–1803: France

- 1803–present: United States (after Louisiana Purchase)

Prehistory and exploration

During prehistoric times, Pushmataha County was part of the territory during the Middle Woodland period of the Fourche Maline culture. Over time, and possibly through contact with the Middle Mississippian culture to their northeast, the Fourche Maline became the Caddoan Mississippian culture. Their center was at Spiro Mounds, near Spiro, Oklahoma. The elite organized the construction of complex earthwork mounds for burial and ritual ceremonial purposes, arranged around a large plaza that had been carefully graded. This center of political and religious leadership had a trade territory encompassing the full extent of the Kiamichi River and Little River valleys. This 80-acre site is preserved as Oklahoma’s only Archeological State Park. The larger Mississippian culture traded from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast.

North America’s history changed after the arrival of Europeans in 1492 under Christopher Columbus in the Caribbean. In the 16th century, European explorers began to enter the North American interior, seeking fame, treasures, and conquests on behalf of their empires.

France’s Bernard de la Harpe explored the area of the modern Pushmataha County in 1719, in the era when France was establishing settlements on the Gulf Coast. They had founded New Orleans the year before. De la Harpe’s exploration of the Mississippi River valley was part of an effort to seek trade with the native peoples and also a route to New Mexico. After this time France claimed this region of North America as La Louisiane. It explored Canada to the north from the Atlantic coast along the St. Lawrence River valley, where it founded New France.

The area that became Pushmataha County was bought by the United States from France as part of the large Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

The first American explorer to set foot in the modern county was Major Stephen H. Long in 1817. He was followed in 1819 by Thomas Nuttall, a scientist. Both explored the Kiamichi River valley, which Nuttall described in detail.

The Red River became an international boundary in 1819 when the United States concluded the Adams-Onis Treaty with the Spanish Empire. Fortifying the frontier from Spanish incursion, and securing it against potential uprisings by American Indians, was important to United States policy. The federal government established a chain of forts along its southern border.

Fort Towson, established at the mouth of Gates Creek on the Kiamichi River, just upstream from its confluence with the Red River, was charged with providing security for the region encompassing modern Pushmataha County. As the fort was built in what was considered frontier wilderness, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers constructed a military road connecting Fort Towson with Fort Smith, Arkansas for purposes of supply and provision. Passing through the Little River valley, this military road was Pushmataha County’s first modern roadway. It lapsed into disuse after Fort Towson was abandoned after the American Civil War. Traces of the road may still be seen.

The Indian Territory

Pushmataha County’s modern origins lie in the Choctaw Nation, during its time as a sovereign nation in the Indian Territory, prior to Oklahoma statehood.

The Choctaw territory comprising the modern county was, until statehood in 1907, divided among two of the three administrative districts, or regions, comprising the nation – Pushmataha and Apukshunnubbee. Each of these districts was subdivided into counties. The modern county fell within Cedar County, Nashoba County and Wade County of the Apukshunnubbee District—today the county’s eastern area – and Jack’s Fork County and Kiamitia County (Kiamichi County) of the Pushmataha District – today the county’s western area.

During the American Civil War federal troops withdrew from the Indian Territory and the Choctaw Nation allied itself with the Confederate States of America. The Choctaw government sent a representative to the Confederate Congress, meeting in the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia, and raised battalions of warriors to participate with Confederate troops.

Although no battles were recorded as occurring within the present-day confines of Pushmataha County, the Battle of Perryville occurred just outside modern-day McAlester and the Battle of Middle Boggy Depot took place outside present-day Atoka. Numerous Choctaws left their homes in the present-day county to join the battalions and participated in the Battle of Pea Ridge, in Arkansas, and at the Battle of Honey Springs in the Cherokee Nation, which pitted them against a Unionist faction of Cherokee Indians.

Contemporary accounts make mention of many refugees streaming through the Kiamichi River valley. The war itself finally ended with the surrender of the last Confederate army—Cherokee General Stand Watie’s forces, who surrendered at Fort Towson in June 1865, over two months after General Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia—and with it any chance of Confederate success.

Sometime before 1862 a Negro slave, Wallace Willis, composed the Negro spiritual “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot”. He was then working at Spencer Academy, a Choctaw Nation boarding school located at Spencervile, Indian Territory. The site of the academy and old Spencerville was located less than 1,000 yards from the current southern border of Pushmataha County. Known as Uncle Wallace, Willis may have resided in Pushmataha County. He died in present-day Atoka County and is buried in an unmarked grave.

The Choctaw people were sedentary. Their lives were tied to their farms and small acreages. The Choctaw Nation was not home to industry of any sort. As a result, the territory comprising modern-day Pushmataha County was still virgin wilderness decades after the Choctaws’ arrival.

During the 1880s the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad – popularly known as the Frisco—built a line from Fort Smith, Arkansas to Paris, Texas. The federal government granted the railroad rights-of-way in Indian Territory to stimulate development and attract European-American settlers. Station stops were established every few miles, both to aid in developing towns and also to serve the railroad.

The Frisco’s route traveled along the Kiamichi River valley, entering the present-day county near Albion and leaving the river only at Antlers, to skirt the massive bluff where it is located.

The railroad stimulated development of businesses and other ties to mainstream United States society. The telegraph was developed and constructed along with the railroad, providing rapid news of events outside the Choctaw Nation.

Logging companies opened operations immediately. Rough-and-tumble sawmill communities began growing up around the railroad station stops. Kosoma, a veritable boomtown, boasted several hotels, doctors’ offices, and general stores during its heyday.

During the next few decades, loggers harvested the entire region, using the railroad stations as transshipment points. These transshipment points developed into the present-day communities of Albion, Moyers, and Antlers. Other communities along the railroad between these points later vanished or are today only place names, such as Kellond, Stanley and Kiamichi.

For decades the Frisco constituted the greatest feat of engineering and manmade structure in Pushmataha County. Workers moved and shaped huge amounts of earth to form its elevated roadbed, and constructed numerous wooden trestles over creeks and rivers. Once in place the railroad attracted commerce and industry, where white men in the Indian Territory hoped to stake a claim.

Although the Five Civilized Tribes of the Indian Territory opposed being incorporated within a United States state, by the turn of the 20th century, statehood of some sort appeared inevitable. A group of leaders from the Five Civilized Nations – Choctaw, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole – met at Muskogee in an attempt to seize the initiative and fashion a state from the Indian Territory, a jurisdiction to be controlled by Native Americans. Their meeting, which came to be known as the Sequoyah Constitutional Convention, established the proposed State of Sequoyah.

The leaders meeting in Muskogee recognized that the counties of the Choctaw Nation, drawn to reflect easily recognizable natural landmarks such as mountain ranges and rivers, were not economically viable. Jack’s Fork County, as example – in which Antlers was located – was a vast territory whose tiny county seat was Many Springs (modern-day Daisy, Oklahoma). But the only commercially successful town within its boundaries was Antlers, and it was situated in its far southeastern corner.

County boundaries for the new State of Sequoyah were crafted to take into account the existing towns and the range of their commercial interests. County seats were centered geographically within the populations of the areas they would govern.

The area comprising modern-day Pushmataha County proved a particular challenge. Huge areas of its eastern portion had few people. Its population was centered in towns along the railroad in the Kiamichi River valley. A county was eventually drawn with the crescent of the Kiamichi River valley forming its commercial heart, and it was to be called Pushmataha County, Sequoyah.

Records of the Sequoyah Constitutional Convention’s committee on counties are lost, and no evidence remains to document the committee’s deliberations. They wanted an area named after their Chief Pushmataha, and singled out the future Pushmataha County, Sequoyah for this honor.

Hugo’s businesses served an area extending as far north as Kent, Speer, Hamden, and nearly to Rattan. As a result, the county boundary for the proposed Hitchcock County – with Hugo as county seat – was established along the line of the existing boundary between Choctaw and Pushmataha counties. Similar considerations governed the establishment of the county’s northern, eastern and western borders.

The United States Congress failed to admit the proposed State of Sequoyah into the Union, preferring to await a possible federation of the Indian Territory and Territory of Oklahoma. This was soon proposed. In 1907 the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention met in Guthrie, Oklahoma Territory to create the new State of Oklahoma. During these deliberations it became clear that the work of the Sequoyah Constitutional Convention had been groundbreaking: the Guthrie meeting essentially adopted nearly the same boundaries for Pushmataha County, Oklahoma as were proposed earlier for it in the state of Sequoyah, again identifying Antlers as county seat.

Since statehood

Pushmataha County at statehood was considered an agricultural paradise. Local residents believed the soil to be fertile and the weather enviable and moderate; it seemed that almost any fruit or vegetable could be grown. Most residents at the time were farmers who lived off their land.

Cotton was king for the county’s first few decades. It was grown throughout the Kiamichi River valley. Growers hauled it into Antlers, Clayton, Albion, and other railroad towns to be weighed and shipped to distant markets on the Frisco Railroad.

Many of the farmers or hired hands were African Americans, descendants of slaves of the Choctaw. After being emancipated following the American Civil War under an 1866 treaties that the United States made with each of the Five Civilized Tribes, African Americans who stayed with the Choctaw were called Choctaw Freedmen. They were granted membership in the nation with voting rights. Others came to the area as laborers in the late 19th century. The county had a significant African-American population in the early 20th century, although this has since dwindled to almost nothing, as people left to seek work. Many African Americans worked in cotton cultivation and, after cotton’s decline, they moved elsewhere for other work.

The territory comprising Pushmataha County had been part of the Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory. It was almost completely unimproved in the European-American sense. The Choctaw government owned land in “severalty”, or common, controlling the communal land. The Choctaw had their own culture and did not need bridges, roads, or public works.

Early business leaders at statehood immediately sought to fund public improvements by asking local voters to pass bonds. The state government did not invest in such infrastructure. Businessmen tried to pass bridge bonds, as example, to build bridges across the Kiamichi River and Jack Fork Creek. These uniformly failed to gain approval, slowing the county’s business development. Choctaw County, by contrast, passed bonds almost immediately, causing bridges to be built throughout the county. This proved excellent for business and commerce, and after this point Hugo grew significantly faster than Antlers.

Pushmataha County began to develop as European Americans settled and founded communities throughout the county. Each community built its own school, and raised money with which to hire a teacher or teachers. Residents also founded churches, mostly of various Protestant denominations with which they were affiliated. Residents of some of the more significant towns, such as Jumbo, Moyers, Clayton and Albion, also established cultural leagues or institutions—poetry clubs, music groups, and literary societies – in a bid for cultural refinement. The Choctaw continued playing a role in the region; its members were elected to local government and served as other government and society leaders in Pushmataha County.

During World War I, county resident Tobias W. Frazier (Choctaw) was a soldier in the U.S. Army and a member of the famous Choctaw Code Talkers. Other Code Talkers were from just over the border in McCurtain County. The fourteen soldiers were part of a pioneering use of American Indian languages as military code during war, to enable secret communications among the Allies. Their contributions helped gain victory and brought World War I to a quicker close.

Federal government programs developed by the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the Great Depression of the 1930s brought substantial improvements and infrastructure to the county: the federal Works Progress Administration (or WPA) directed the construction with local workers of handsome, sturdy schools and school gymnasiums in numerous communities. The new buildings were built of native “red rock” gathered in nearby fields. They aged very well. Several are still in use, notably in Moyers, Rattan and Antlers. But the school at Jumbo was bulldozed by a local farmer in the 1990s to clear the field for cattle.

The Rural Electrification Administration provided guidance and funding to bring electricity to the rural county; electrical lines were strung, connecting homes to the electrical grid. These changes improved indoor conditions, and people began to acquire air conditioning and television from the 1950s on. People more often conducted their social lives inside rather than on town streets. Architectural design changed, as stores, churches and homes no longer had to allow for maximum ventilation via the free flow of air from open windows and doors.

Highways were paved and standardized in the 1950s, making travel easier and linking farms and countryside to the town markets, and the towns to one another. As people bought more automobiles, they stopped using the railroad. The Frisco ceased passenger operations in the late 1950s as unprofitable. Wholesale changes resulted from railroad restructuring in the later 20th century, and the Frisco ended freight operations in the early 1980s. At that time the trestle bridges were dismantled, rails removed and the roadbed was abandoned to nature.

The Indian Nation Turnpike, which opened in 1970, had only one interchange in all of Pushmataha County, at Antlers, connecting residents to freeway travel to Oklahoma City and Tulsa.

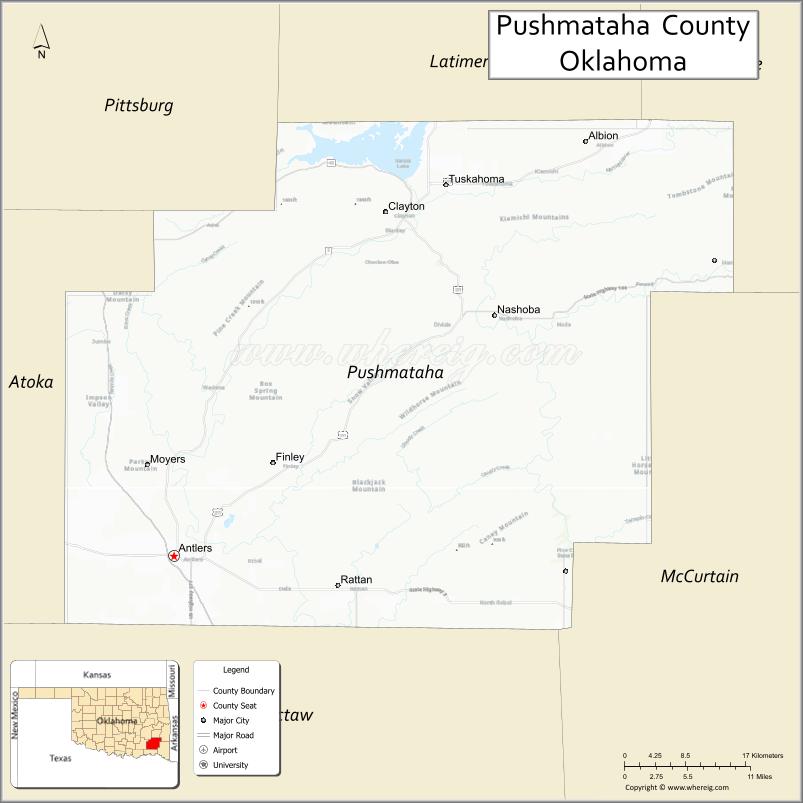

Pushmataha County Road Map

Geography

Pushmataha County’s location in southeastern Oklahoma places it in a 10-county area designated for tourism purposes by the Oklahoma Department of Tourism and Recreation as Choctaw Country, previously Kiamichi Country. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 1,423 square miles (3,690 km), of which 1,396 square miles (3,620 km) is land and 27 square miles (70 km) (1.9%) is water.

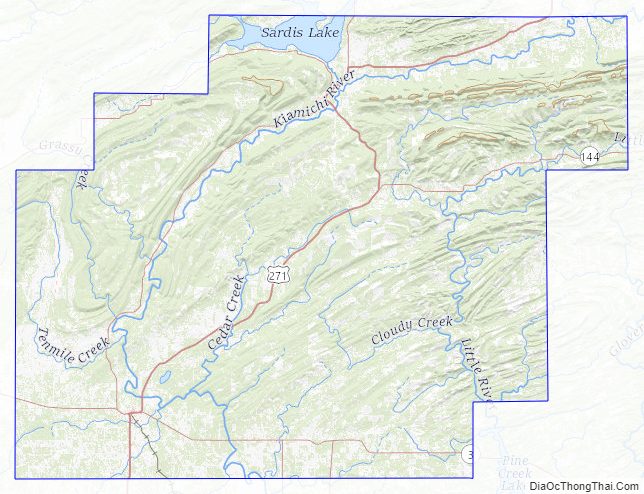

Most of Pushmataha County is mountainous, with the exception of a relatively flat agricultural belt along the county’s southern border. The Kiamichi River valley forms a crescent through the county from northeast to southwest. As was typical in prehistoric times, most human habitation has continued to be along this crescent.

The Kiamichi Mountains, a sub-range of the Ouachita Mountains, occupy most of the land in the county. This mountain chain has never been formally defined, nor have its neighboring mountain chains, such as the Winding Stair Mountains to the county’s north or the Bok Tuklo Mountains to its east. The Kiamichi Mountains range to a height of approximately 1,650 feet (500 m) in the county. Many of its summits are in the shape of long furrows. The mountains are difficult to penetrate with road construction and large areas of the county are virtually empty of population.

Two rivers, the Kiamichi and Little River, flow through the county with their numerous tributaries. Sardis Lake, a flood-control facility in the northeastern part of the county, impounds the waters of Jack Fork Creek. Hugo Lake, in Choctaw County, provides a similar function on the main stem of the river. It backs up the Kiamichi River northward into the county. Smaller impoundments include Clayton Lake, Nanih Waiyah Lake, Ozzie Cobb Lake and Pine Creek Lake.

Major tributaries of the Kiamichi River include Jack Fork Creek, Buck Creek, and Ten Mile Creek. Black Fork Creek and Pine Creek are the most significant tributaries of Little River.

Interesting geographical features in the county include Rock Town, a small region of distinctive boulders in Johns Valley; Umbrella Rock near Clayton; McKinley Rocks near Tuskahoma; and the Potato Hills—unusually serrated landforms near Tuskahoma.

Adjacent counties

- Latimer County (north)

- Le Flore County (northeast)

- McCurtain County (east)

- Choctaw County (south)

- Atoka County (west)

- Pittsburg County (northwest)

Major highways

- Indian Nation Turnpike

- Oklahoma State Highway 2

- Oklahoma State Highway 3

- Oklahoma State Highway 43

- Oklahoma State Highway 93

- Oklahoma State Highway 144

- U.S. Highway 271

Pushmataha County Topographic Map

Pushmataha County Satellite Map

Pushmataha County Outline Map

See also

Map of Oklahoma State and its subdivision:- Adair

- Alfalfa

- Atoka

- Beaver

- Beckham

- Blaine

- Bryan

- Caddo

- Canadian

- Carter

- Cherokee

- Choctaw

- Cimarron

- Cleveland

- Coal

- Comanche

- Cotton

- Craig

- Creek

- Custer

- Delaware

- Dewey

- Ellis

- Garfield

- Garvin

- Grady

- Grant

- Greer

- Harmon

- Harper

- Haskell

- Hughes

- Jackson

- Jefferson

- Johnston

- Kay

- Kingfisher

- Kiowa

- Latimer

- Le Flore

- Lincoln

- Logan

- Love

- Major

- Marshall

- Mayes

- McClain

- McCurtain

- McIntosh

- Murray

- Muskogee

- Noble

- Nowata

- Okfuskee

- Oklahoma

- Okmulgee

- Osage

- Ottawa

- Pawnee

- Payne

- Pittsburg

- Pontotoc

- Pottawatomie

- Pushmataha

- Roger Mills

- Rogers

- Seminole

- Sequoyah

- Stephens

- Texas

- Tillman

- Tulsa

- Wagoner

- Washington

- Washita

- Woods

- Woodward

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming