Columbia is a census-designated place in Howard County, Maryland, United States. It is a planned community consisting of 10 self-contained villages. The census-designated place had a population of 104,681 at the 2020 census, making it the second most populous community in Maryland after Baltimore. Columbia, located between Baltimore and Washington, D.C., is officially part of the Baltimore metropolitan area.

Columbia proper consists only of that territory governed by the Columbia Association, but larger areas are included under its name by the U.S. Postal Service and the Census Bureau. These include several other communities which predate Columbia, including Simpsonville, Atholton, and in the case of the census, part of Clarksville. Columbia began with the idea that a city could enhance its residents’ quality of life. Developer James Rouse attempted to create the new community in terms of human values, rather than economics and engineering. Opened in 1967, Columbia was intended to not only eliminate the inconveniences of then-current subdivision design, but also eliminate racial, religious and class segregation.

| Name: | Columbia CDP |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 57 |

| LSAD Description: | CDP (suffix) |

| State: | Maryland |

| County: | Howard County |

| Founded: | June 21, 1967 |

| Elevation: | 407 ft (124 m) |

| Total Area: | 32.19 sq mi (83.37 km²) |

| Land Area: | 31.93 sq mi (82.71 km²) |

| Water Area: | 0.26 sq mi (0.66 km²) |

| Total Population: | 104,681 |

| Population Density: | 3,278.04/sq mi (1,265.68/km²) |

| ZIP code: | 21044-21046 |

| FIPS code: | 2419125 |

| GNISfeature ID: | 0590002 |

| Website: | columbiaassociation.com |

Online Interactive Map

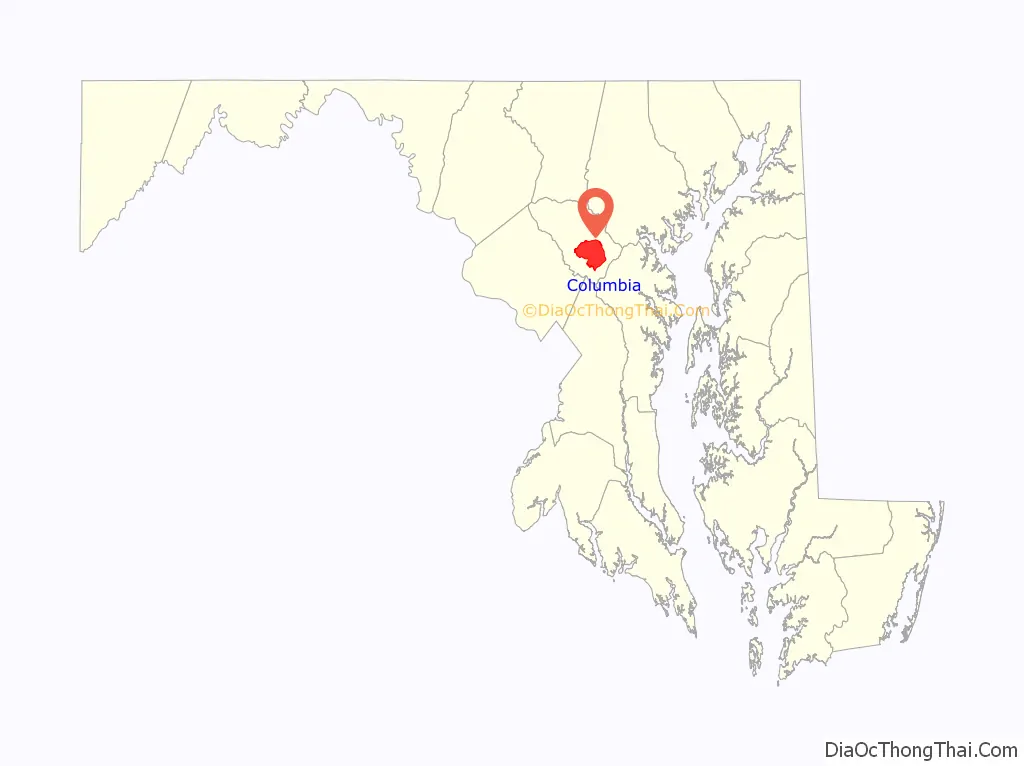

Columbia location map. Where is Columbia CDP?

History

Origins

Columbia was founded by James W. Rouse (1914-1996), a native of Easton, Maryland. In 1935, Rouse obtained a job in Baltimore with the Federal Housing Administration, a New Deal agency whose purpose was to promote home ownership and home construction. This position exposed Rouse to all phases of the housing industry. Later in the 1930s he co-founded a Baltimore mortgage banking business, the Moss-Rouse Company. In the 1950s his company, by then known as James W. Rouse and Company, branched out into developing shopping centers and malls. In 1957, Rouse formed Community Research and Development, Inc. (CRD) for the purpose of building, owning and operating shopping centers throughout the country. Community Research and Development, Inc., which was managed by James W. Rouse and Company, became a publicly traded company in 1961. In 1966, Community Research and Development, Inc. changed its name to The Rouse Company, after it had acquired James W. Rouse and Company in exchange for company stock.

By the early 1950s Rouse was also active in organizations whose goals were to combat blight and promote urban renewal. Along the way, he came to recognize the importance of comprehensive planning and action to address housing issues. A talented public speaker, Rouse’s speeches on housing matters attracted media attention. By the mid-1950s he was espousing his belief that in order to be successful, cities had to be places where people succeeded. In a 1959 speech he declared that the purpose of cities is for people, and that the objective of city planning should be to make a city into neighborhoods where men, women, and their families can live and work, and, most importantly, grow in character, personality, religious fulfillment, brotherhood, and the capacity for joyous living.

In the early 1960s, Rouse decided to develop a new model city. Rouse’s ideas about what a new model city should be like were informed by a number of factors, including his personal Christian faith as well as the goal for his company to earn a profit, influences that he did not consider to be incompatible with one another. After exploring possible new city locations near Atlanta, Georgia, and Raleigh-Durham, North Carolina, Rouse focused his attention between Baltimore and Washington, D.C., in Howard County, Maryland.

Howard County land acquisition

In April 1962, Mel Berman, a longtime Howard County resident who was also a member of the CRD’s Board of Directors, saw a sign on Cedar Lane in Howard County advertising 1,309 acres (530 ha) for sale. Berman reported the option to the CRD and a decision was made to purchase the land. This was the first of 165 land purchases made by Rouse over the next year-and-a-half. In order to keep land costs low, Jack Jones, an attorney from Rouse’s firm of Piper Marbury, set up a grid system to secretly buy land through dummy corporations like the “Alaska Iron Mines Company”. Some of these straw purchasers included Columbia Industrial Development Corporation, 95-32 Corporation, 95-216 Corporation, Premble, Inc., Columbia Mall, Inc., Oakland Ridge Industrial Development Corporation, and Columbia Development Corporation. Robert Moxley’s firm Security Realty Company (now Security Development Group Inc), negotiated many of the land deals for Jones, becoming his best client. CRD accumulated 14,178 acres (57.38 km), 10 percent of Howard County, from 140 separate owners. Rouse was turned down in financing from David Rockefeller, who had recently cancelled a planned Rouse “Village” concept called Pocantico Hills. The $19,122,622 acquisition was then funded by Rouse’s former employer Connecticut General Life Insurance in October 1962 at an average price of $1,500 per acre ($0.37/m). The town center land of Oakland Manor was purchased from Isadore Guldesky who was turned down from building high-rises on the site by Rob Moxley’s brother, County Commissioner and land developer Norman E. Moxley. Sensing that he had a key property, he requested $5 million for his 1,000 acres (400 ha), signing an agreement by hand on a land plat. The competition between Rouse and Guldesky carried over to the competing Tysons Corner Center and Tysons Galleria projects, with each hiring their competitor’s employees.

By late 1962, citizens had elected an all-Republican three-member council. J. Hubert Black, Charles E. Miller, and David W. Force who campaigned on a low-density growth ballot, but later approved the Columbia project. The Howard County Planning Commission Chairman Wilmer Sanner declared, “if this adds to the orderly development of the county, that’s what we are looking for.” That July, Sanner sold the majority of his 73-acre (30 ha) Simpsonville farm to Howard Research prior to the public announcement. In October 1963, the acquisition was revealed to the residents of Howard County, putting to rest rumors about the mysterious purchases. These had included theories that the site was to become a medical research laboratory or a giant compost heap. Despite the moniker of being a “planned city”, the planning for the city occupied Rouse officials for most of 1964 after the announcement while marketing director Scott Ditch was brought from Baltimore’s Cross Keys development to promote the project to community groups.

In December 1964 the zoning was rejected by planning director Tom Harris Jr. for handing nearly all planning control to the developer. A media push was instituted to approve the zoning by Dorris Thompson of The Howard County Times, Seymour Barondes of the Howard County Civic Association, and Anita Iribe of the League of Women Voters. In June 1965 zoning was approved for the project, and Howard Research and Development entered into a $37.5 million construction deed backed by the property. Development was temporarily stalled in October 1965 when James and Anna Hepding of Simpsonville sued the planning board, stating New Town zoning was a form of spot zoning benefiting a sole property owner. The case was dropped when developer Homer Gudelsky purchased the estate. Ten years later, former Councilman Charles E. Miller stated that if he could do it over again, he wouldn’t have voted to approve Columbia. He felt exploited and felt the subsidized housing would become a problem for the rest of the county. Miller had been defeated in the November 1974 Howard County Council elections, in part as a result of the changed political landscape that Columbia’s development brought. In early 1976, a Columbia Flier editorial charged that Miller was a fear-mongering reactionary who had a personal vendetta against Columbia, Rouse and Columbia residents.

Unveiling and growth

At the unveiling on June 21, 1967, James Rouse described Columbia as a planned new city which would avoid the leap-frog and spot-zoning development threatening the county. The new city would be complete with jobs, schools, shopping, and medical services, and a range of housing choices. Property taxes from commercial development would cover the additional services with which housing would burden the county. The urban planning process for Columbia included not only planners, but also a convened panel of nationally recognized experts in the social sciences, known as the Work Group. The fourteen member group of men and one woman, Antonia Handler Chayes, met for two days, twice a month, for half a year starting in 1963. The Work Group suggested innovations for planners in education, recreation, religion, and health care, as well as ways of improving social interactions. Columbia’s open classrooms, interfaith centers, and the then-novel idea of a health maintenance organization (HMO) with a group practice of medical doctors (the Columbia Medical Plan) sprung from these meetings. The community’s physical plan, with neighborhood and village centers, was also decided. Columbia’s “New Town District” zoning ordinance gave developers great flexibility about what to put where, without requiring county approval for each specific project.

In 1968, vice-presidential candidate Spiro Agnew referenced Columbia to reporters, saying, “Government should act as a catalyst to encourage the local governments to encourage industry and business to move next to a planned community,” and “I want to lessen the density in the ghettos, and concurrently rebuild the ghetto areas.” In 1969, County Executive Omar J. Jones felt that the increase in tax base was lagging behind the need for infrastructure as the operating budget doubled to $15 million in three years. Crime rates shot up around the county by 30-50% a year, with hot spots around the development. By 1970, the project required additional financing to continue, borrowing $30 million from Connecticut General, Manufacturers Hanover Trust, and Morgan Guaranty. In 1972, amendments to New Town zoning proposing to place a maximum height for buildings and maintain the original density limit of 2.2 units per acre were opposed by Rouse allies including the Columbia Association, the Ellicott City Businessman’s Association and the Columbia Democratic Club. By 1974, the amount owed reached $100,000 million, prompting partner Connecticut General to consider bankruptcy. An effort to create a special taxing district in 1978 and an effort to incorporate with a mayor in 1979 failed. In 1985 Cigna (Connecticut General) divested itself of the project for $120 million. By 1990 Howard Research and Development owed $125,162,689. In 2004 the project was sold to General Growth Properties, which went bankrupt in 2008. General Growth Properties submitted a plan for increasing density throughout Columbia in 2004 which was unanimously voted down. Ownership of the project fell to the previous Rouse subsidiary the Howard Hughes Corporation. Howard Hughes submitted a new plan to increase density in 2010 under the Ulman administration that passed unanimously.

Columbia has never incorporated; some governance, however, is provided by the non-profit Columbia Association, which manages common areas and functions as a homeowner association with regard to private property. The first boards were filled entirely with Rouse Company appointees. The first manager of the Columbia Association was John Estabrook Slayton (d. 1967). For Slayton’s contributions to the early planning of Columbia, the community center in the Wilde Lake village, Slayton House, was named for him. Wilde Lake was the first village area to be developed in Columbia; accordingly, the town’s first high school was Wilde Lake High School, which opened in 1971 as a “model school for the nation”. Constructed in the open classroom style, it was razed in 1994 but reconstructed on the same site in 1996.

Master plan

To achieve the goals set forth by the Work Group, Columbia’s Master Plan called for a series of ten self-contained villages, around which day-to-day life would revolve. The centerpiece of Columbia would be The Mall in Columbia and man-made Lake Kittamaqundi.

The village concept aimed to provide Columbia a small-town feel (like Easton, Maryland, where James Rouse grew up). Each village comprises several neighborhoods. The village center may contain middle and high schools. All villages have a shopping center, recreational facilities, a community center, a system of bike/walking paths, and homes. Four of the villages have interfaith centers, common worship facilities which are owned and jointly operated by a variety of religious congregations working together.

Most of Columbia’s neighborhoods contain single-family homes, townhomes, condominiums and apartments, though some are more exclusive than others. The original plan, following the neighborhood concept of Clarence Perry, would have had all the children of a neighborhood attend the same school, melding neighborhoods into a community and ensuring that all of Columbia’s children get the same high-quality education. Rouse marketed the city as being “color blind” as a proponent of Senator Clark’s fair housing legislation. If a neighborhood was filled with too many purchasers of a single race, houses would be blocked until the desired ratio was met.

- Village – Neighborhoods (in order of residential opening)

- Wilde Lake – (Est. 1967) Bryant Woods, Faulkner Ridge, Running Brook

- Harper’s Choice – (Est. 1968) Longfellow, Swansfield, Hobbit’s Glen

- Oakland Mills – (Est. 1969) Thunder Hill, Talbott Springs, Stevens Forest

- Long Reach – (Est. 1971) Phelps Luck, Jeffers Hill, Locust Park, Kendall Ridge

- Owen Brown – (Est. 1972) Dasher Green, Elkhorn, Hopewell

- Town Center – (Est. 1974) Vantage Point, Banneker, Amesbury, Creighton’s Run, and Warfield Triangle

- Hickory Ridge – (Est. 1974) Clemens Crossing, Hawthorn, Clary’s Forest

- Kings Contrivance – (Est. 1977) Macgill’s Common, Huntington, Dickinson

- Dorsey’s Search – (Est. 1980) Dorsey Hall, Fairway Hills

- River Hill – (Est. 1990) Pheasant Ridge, Pointers Run

Columbia takes its street names from famous works of art and literature: for example, the neighborhood of Hobbit’s Glen takes its street names from the work of J. R. R. Tolkien; Running Brook, from the poetry of Robert Frost; and Clemens Crossing, from the work of Mark Twain. The book Oh, You Must Live in Columbia! chronicles the artistic, poetic, and historical origins of the street and place names in Columbia.

Further expansion

“The Downtown Columbia Plan” is a 2010 amendment to the county’s General Plan of expansion. It is a framework for the revitalization of Downtown Columbia over the next thirty years. Development plans for downtown projects in the years ahead will include details for that project such as neighborhood design guidelines, environmental restoration, public amenities and infrastructure. These development plans must adhere to the framework of the Downtown Columbia Plan as required by the zoning legislation. Over the life of the Downtown Columbia development project, as much as 13 million square feet of retail, commercial, residential, hotel and cultural development is planned.

To be accomplished in three phases, the plan calls for the formation of the non-profit Columbia Downtown Housing Corporation to build an additional 5,500 units of low income housing placed downtown in exchange for increased zoning density for other projects. Additional development includes 4.3 million square feet of commercial office space, 1.25 million square feet of retail space, 640 hotel rooms, Merriweather Post Pavilion redevelopment and a multi-modal transportation system.

The Downtown Columbia Plan also has sustainability features, including goals for saving water and energy, and for ecology and livability.

Columbia’s master developer, the Howard Hughes Corporation, is heading up the expansion project. The project is projected to cost $90 million and will outline development in the community for the next 40 years.

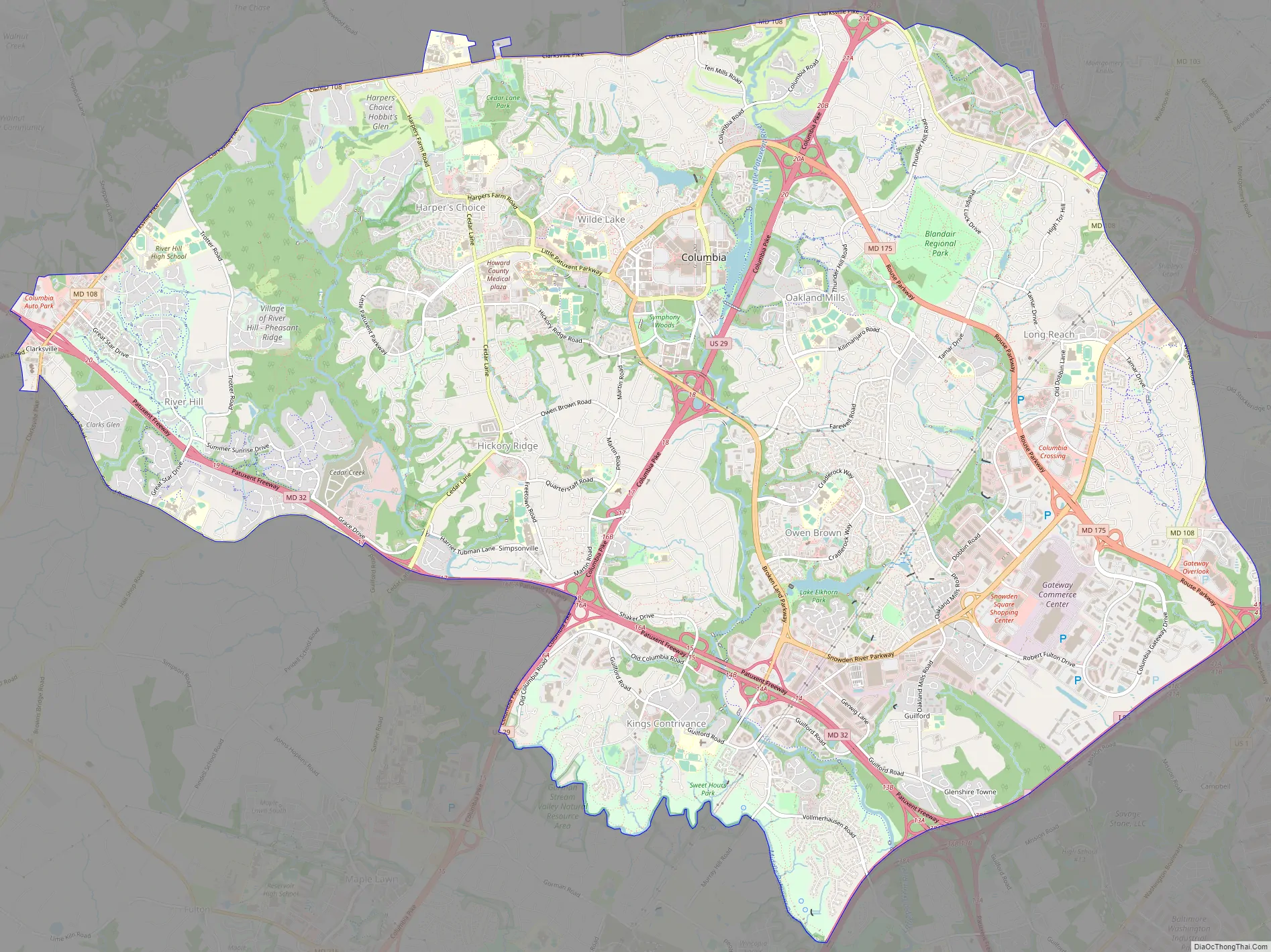

Columbia Road Map

Columbia city Satellite Map

Geography

Because Columbia is unincorporated, there is confusion over its exact boundaries. In the strictest definition, Columbia comprises only the land governed under covenants by the Columbia Association. This is a considerably smaller area than the census-designated place (CDP) as defined by the United States Census Bureau. The CDP has a total area of 32.2 square miles (83.4 km), of which 31.9 square miles (82.7 km) are land and 0.3 square miles (0.7 km), or 0.80%, are water. The CDP includes a number of older communities which do not lie within the CA’s purview, including the Holiday Hills, Diamondback, and Allview subdivisions and the former town of Simpsonville, as well as some land on the east side of Clarksville. These areas are not part of the “new town”, and are not directly served by its amenities. Some of these areas are included in Columbia ZIP codes by the post office, and some are not.

Columbia is located in central Maryland, 20 miles (32 km) southwest of Baltimore, 25 miles (40 km) northeast of Washington, D.C., and 30 miles (48 km) northwest of Annapolis. The community lies in the Piedmont region of Maryland, with its eastern edge at the fall line. The climate tends to hot, humid summers and cool to cold and wet winters. There are occasional large amounts of snowfall that happen every year.

The primary landforms in Columbia are rolling hills and stream valleys; Columbia’s road network is laid out to follow the terrain, with many winding streets and cul-de-sacs. Elevations range from about 200 to 500 feet (61 to 152 m) above sea level. Most of Columbia is drained by the Middle Patuxent and Little Patuxent rivers. There are three artificial lakes, created by damming of tributary streams during community construction. In 1965, the Rouse Company leased 7,000 acres (2,800 ha) of farmland staged for development, and earmarked 4,000 acres (1,600 ha) of oak forest for timber harvesting. The company developed a sapling planter to replant sections of cleared land that would use Columbia’s W.R. Grace-developed fertilizers. An outer ring of greenspace was abandoned early in the project because the combination with the already required river buffers would have reduced profitable land available for building. Along with Symphony Woods, many other stands of mature trees have been temporarily maintained in Columbia, including the large Middle Patuxent Environmental Area in the western part of the community between Harper’s Choice and River Hill villages, protecting much of the river valley from development.

Climate

Columbia has a humid subtropical climate, with cool winters and hot, muggy summers.

See also

Map of Maryland State and its subdivision: Map of other states:- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming