Richmond (/ˈrɪtʃmənd/) is the capital city of the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. It is the center of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Greater Richmond Region. Richmond was incorporated in 1742 and has been an independent city since 1871. At the 2010 census, the city’s population was 204,214; in 2020, the population had grown to 226,610, making Richmond the fourth-most populous city in Virginia. The Richmond Metropolitan Area has a population of 1,260,029, the third-most populous metro in the state.

Richmond is at the fall line of the James River, 44 mi (71 km) west of Williamsburg, 66 mi (106 km) east of Charlottesville, 91 mi (146 km) east of Lynchburg and 92 mi (148 km) south of Washington, D.C. Surrounded by Henrico and Chesterfield counties, the city is at the intersections of Interstate 95 and Interstate 64 and encircled by Interstate 295, Virginia State Route 150 and Virginia State Route 288. Major suburbs include Midlothian to the southwest, Chesterfield to the south, Varina to the southeast, Sandston to the east, Glen Allen to the north and west, Short Pump to the west and Mechanicsville to the northeast.

The site of Richmond had been an important village of the Powhatan Confederacy, and was briefly settled by English colonists from Jamestown from 1609 to 1611. The present city of Richmond was founded in 1737. It became the capital of the Colony and Dominion of Virginia in 1780, replacing Williamsburg. During the Revolutionary War period, several notable events occurred in the city, including Patrick Henry’s “Give me liberty, or give me death!” speech in 1775 at St. John’s Church, and the passage of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom written by Thomas Jefferson. During the American Civil War, Richmond was the capital of the Confederacy. It entered the 20th century with one of the world’s first successful electric streetcar systems. The Jackson Ward neighborhood is a traditional hub of African-American commerce and culture.

Richmond’s economy is primarily driven by law, finance, and government, with federal, state, and local governmental agencies, as well as notable legal and banking firms in the downtown area. The city is home to both a U.S. Court of Appeals, one of 13 such courts, and a Federal Reserve Bank, one of 12 such banks. There are several Fortune 500 companies headquartered in the city including: Dominion Energy, WestRock, Performance Food Group, CarMax, ARKO, and Altria with others, such as Markel, in the metropolitan area.

| Name: | Richmond City |

|---|---|

| FIPS code: | 51-760 |

| State: | Virginia |

| Named for: | Richmond, United Kingdom |

| Land Area: | 59.92 sq mi (155.20 km²) |

| Population Density: | 3,782/sq mi (1,484.75/km²) |

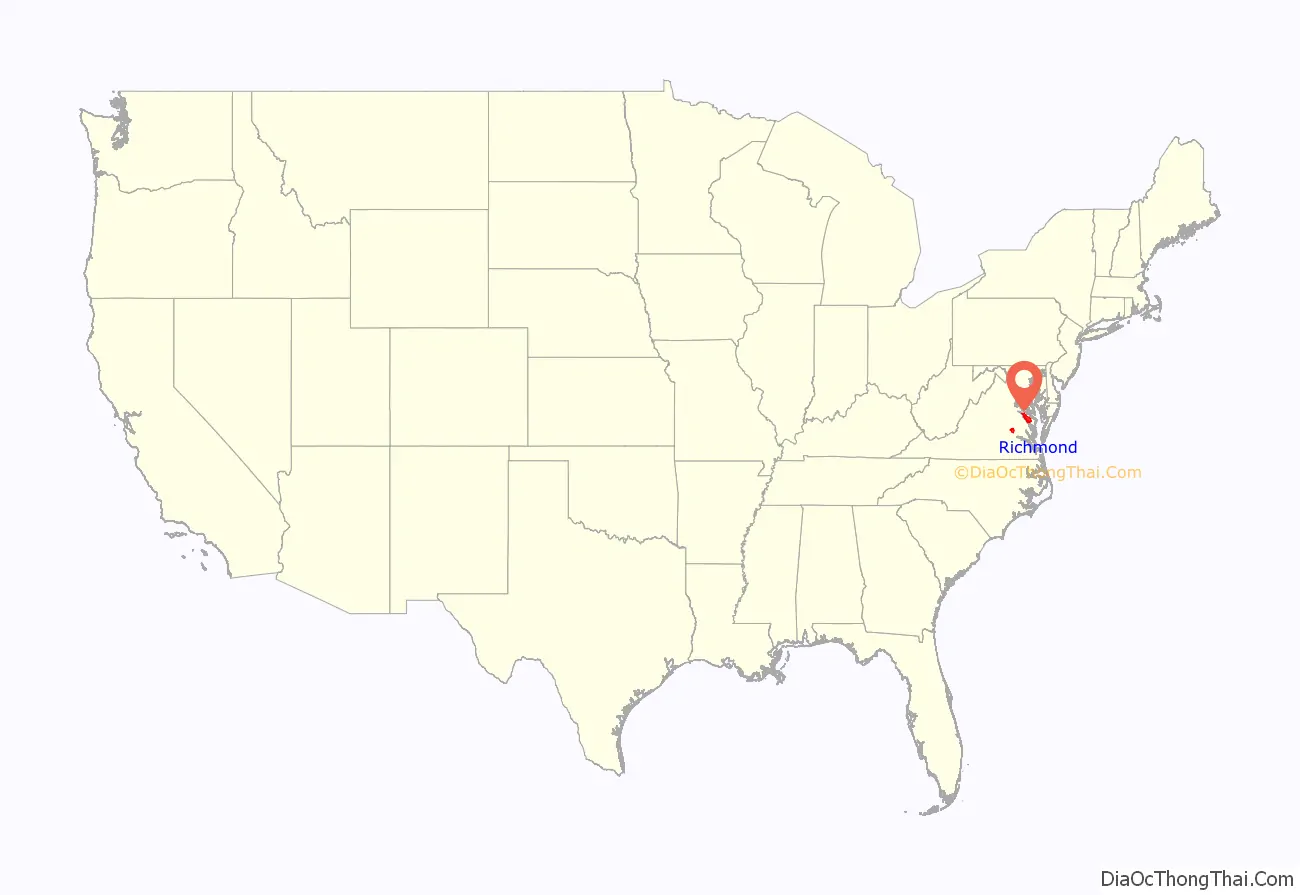

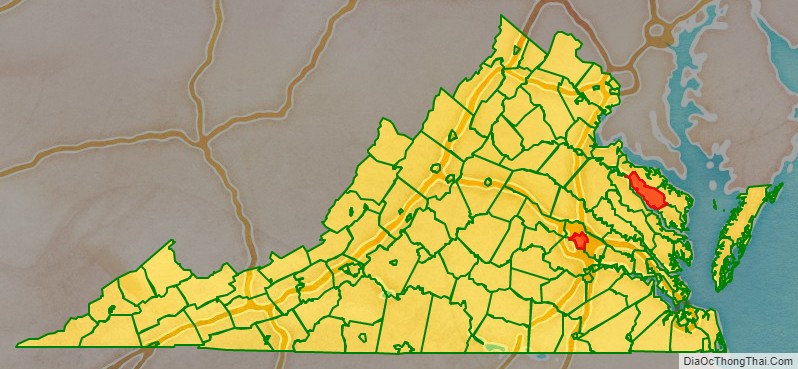

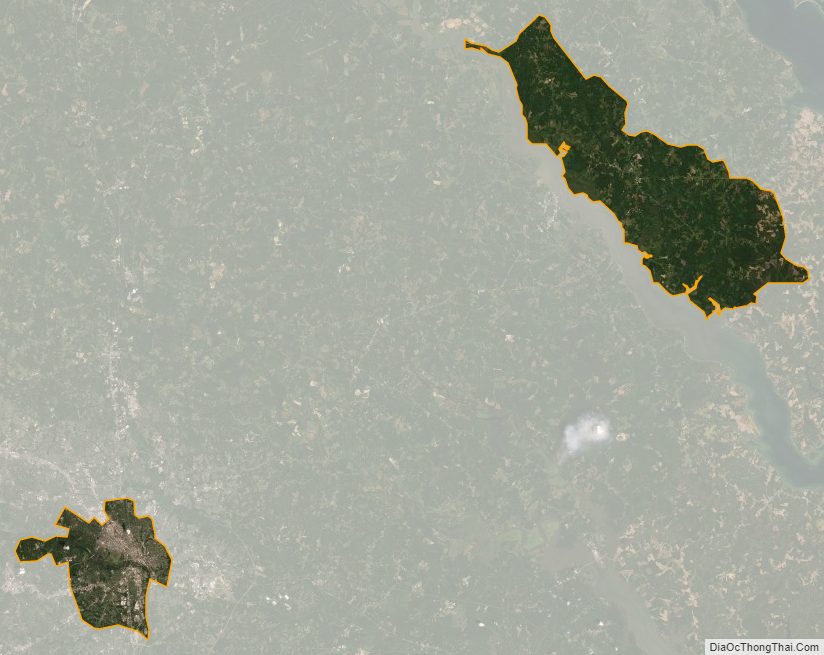

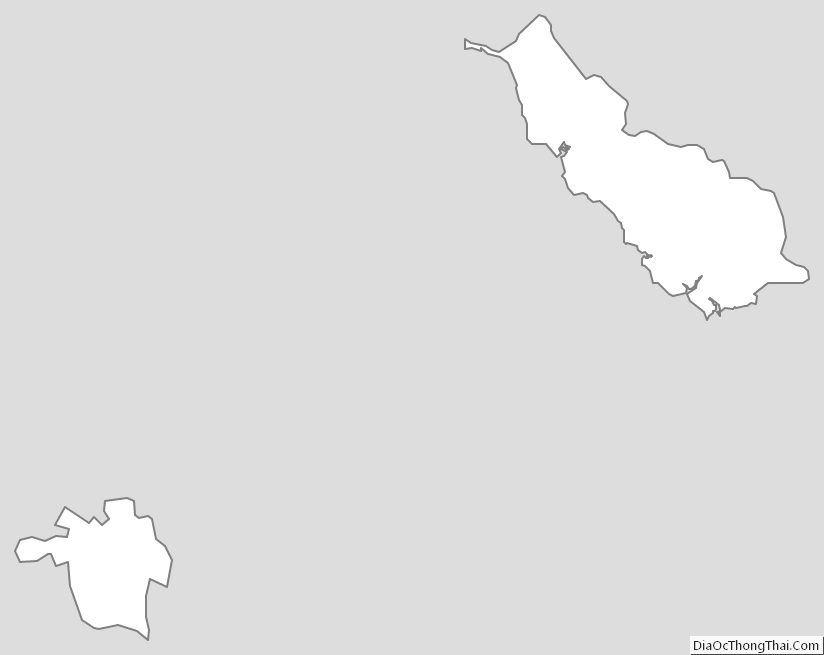

Richmond City location map. Where is Richmond City?

History

Colonial era

After the first permanent English-speaking settlement was established in April 1607, at Jamestown, Virginia, Captain Christopher Newport led explorers northwest up the James River to an inhabited area within the Powhatan Nation.

The earliest European settlement in Central Virginia was in 1611 at Henricus, where the Falling Creek empties into the James River. In 1619 early Virginia Company settlers struggling to establish viable moneymaking industries established the Falling Creek Ironworks. After decades of conflicts between the Powhatan and the settlers, the Falls of the James saw more White settlement in the late 1600s and early 1700s.

The Battle of Bloody Run was fought near Richmond in 1656, after an influx of Manahoacs and Nahyssans from the North.

In 1737 planter William Byrd II commissioned Major William Mayo to lay out the original town grid. Byrd named the city after the English town of Richmond near (and now part of) London, because the view of the bend in the James River at the fall line was similar to the view of the River Thames from Richmond Hill in England (which was in turn named after Henry VII’s ancestral town of Richmond, North Yorkshire), where he had spent time during his youth. The settlement was laid out in April 1737 and incorporated as a town in 1742.

Revolution

In 1775 Patrick Henry delivered his famous “Give me liberty, or give me death” speech in St. John’s Church in Richmond, crucial for deciding Virginia’s participation in the First Continental Congress and setting the course for revolution and independence. On April 18, 1780, the state capital was moved from the colonial capital of Williamsburg to Richmond, to provide a more centralized location for Virginia’s increasing westerly population, as well as to isolate the capital from British attack. The latter motive proved to be in vain, and in 1781, under the command of Benedict Arnold, Richmond was burned by British troops, causing Governor Thomas Jefferson to flee as the Virginia militia, led by Sampson Mathews, defended the city.

Early United States

Richmond recovered quickly from the war, and by 1782 was once again a thriving city. In 1786 the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (drafted by Thomas Jefferson, 1743–1826) was passed at the temporary capitol in Richmond, providing the basis for the separation of church and state, a key element in the development of freedom of religion in the United States. A permanent home for the new government, the Greek Revival style of the Virginia State Capitol building, was designed by Jefferson with the assistance of Charles-Louis Clérisseau and completed in 1788.

After the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), Richmond emerged as an important industrial center. To facilitate the transfer of cargo from the flat-bottomed James River bateaux above the fall line to the ocean-faring ships below, George Washington helped design the James River and Kanawha Canal from Westham east to Richmond, to bypass Richmond’s rapids on the upper James River with the intent of providing a water route across the Appalachian Mountains to the Kanawha River flowing westward into the Ohio then eventually to the Mississippi River. The legacy of the canal boatmen is represented by the figure in the center of the city flag. As a result of this and ample access to hydropower due to the falls, Richmond became home to some of the country’s largest manufacturing facilities, including iron works and flour mills, the largest of their kind in the South. The resistance to the slave trade was growing by the mid-19th century; in one famous 1849 case, Henry “Box” Brown made history by having himself nailed into a small box and shipped from Richmond through Baltimore‘s President Street Station northward on the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad (a well-used “Underground Railroad” route for escaping disguised slaves) to abolitionists in Philadelphia, in the free state of Pennsylvania, escaping slavery. By 1850 Richmond was connected by the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad to Port Walthall, where ships carrying over 200 tons of cargo could connect to Baltimore or Philadelphia and passenger liners could reach Norfolk, Virginia, through the Hampton Roads harbor. In the 19th century Richmond was connected to the North by the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad, which was later replaced by CSXT.

American Civil War

On April 17, 1861, five days after the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, the state legislature voted to secede from the United States and join the newly created Confederate States of America. Official action came in May, after the Confederacy promised to move its national capital to Richmond from its temporary home in Montgomery, Alabama. However, the new capital was at the end of a long supply line, which made it difficult to defend. For four years its defense required the bulk of the Army of Northern Virginia and the Confederacy’s best troops and commanders. It became the main target of Union armies, especially in the campaigns of 1862 and 1864–65.

Richmond held local, state and national government offices. hospitals, a railroad hub, and one of the largest slave markets. It also had the largest arms factory during the war, the Tredegar Iron Works. It produced artillery and other munitions, including the 723 tons of armor plating that covered the CSS Virginia the world’s first ironclad warship used in war, as well as much of the Confederates’ heavy ordnance machinery. The Confederate States Congress shared quarters with the Virginia General Assembly in Jefferson’s designed Virginia State Capitol, with the Confederacy’s executive mansion, known as the “White House of the Confederacy”, two blocks away on Clay Street. The Seven Days Battles followed in late June and early July 1862, during which commanding Union General-in-Chief George B. McClellan threatened to take Richmond in the Peninsula campaign but failed.

Three years later, in March 1865, Richmond became indefensible after nearby Petersburg and several remaining rail supply lines to the south and southwest were broken. On March 25 Confederate General John B. Gordon’s desperate attack on Fort Stedman east of Petersburg failed. On April 1 Federal Cavalry General Philip Sheridan, assigned to interdict the Southside Railroad, met brigades commanded by Southern General George Pickett at the Five Forks junction, smashing them, taking thousands of prisoners, and encouraging Union General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant to order a general advance. When the Union Sixth Corps broke through Confederate lines on the Boydton Plank Road south of Petersburg, Confederate casualties exceeded 5,000, about a tenth of Lee’s defending army. Lee then informed President Jefferson Davis that he was about to evacuate Richmond.

The Confederate Army began the evacuation of Richmond on April 2, 1865. Davis and his cabinet, along with the government archives and Treasury gold, left the city by train that night, as government officials burned documents and departing Confederate troops burned tobacco and other warehouses to deny their contents to the victors. In the early a.m. of the following day, Confederate troops exploded the gunpowder magazine, resulting in the death of several paupers residing in the temporary Almshouse. It was on April 3, 1865, General Godfrey Weitzel, commander of the 25th Corps of the United States Colored Troops, accepted the city’s surrender from the mayor and a group of leading citizens who remained. The Union troops eventually stopped the raging fires but about 25% of the city’s buildings were destroyed.

President Abraham Lincoln visited Grant at Petersburg on April 3, and took a launch to Richmond up the James River the next day, while Davis attempted to organize his remaining Confederate government further southwest at Danville. Lincoln met Confederate assistant secretary of War John A. Campbell, and handed him a note inviting Virginia’s state legislature to end their rebellion. After Campbell spun the note to Confederate legislators as a possible end to the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln rescinded his offer and ordered Weitzel to prevent the former Confederate state legislature from meeting. Union forces killed, wounded or captured 8,000 Confederate troops at Sayler’s Creek southwest of Petersburg on April 6, as the Southerners continued a general retreat southwestward. Lee continued to reject Grant’s surrender suggestions until Sheridan’s infantry and cavalry moved around the shrinking Army of Northern Virginia and appeared in front of his withdrawing forces on April 8, cutting off the line of further retreat southwest. He surrendered his remaining approximately 10,000 troops at Appomattox Court House, meeting Grant the following morning at the McLean Home. Davis was captured on May 10 near Irwinville, Georgia, and taken back to Virginia, where he was imprisoned for two years at Fort Monroe until freed on bail.

Postbellum

Richmond emerged a decade after the smoldering rubble of the Civil War to resume its position as an economic powerhouse, with iron front buildings and massive brick factories. Canal traffic peaked in the 1860s and slowly gave way to railroads, allowing Richmond to become a major railroad crossroads, eventually including the site of the world’s first triple railroad crossing. Tobacco warehousing and processing continued to play a role, boosted by the world’s first cigarette-rolling machine, invented by James Albert Bonsack of Roanoke in 1880/81. Contributing to Richmond’s resurgence was the country’s first successful electrically powered trolley system, the Richmond Union Passenger Railway. Designed by electric power pioneer Frank J. Sprague, the system opened its first line in 1888, and electric streetcar lines rapidly spread to other cities. Sprague’s system used an overhead wire and trolley pole to collect current, with electric motors on the car’s trucks. Transition from streetcars to buses began in May 1947 and was completed on November 25, 1949.

20th century

By the beginning of the 20th century the city’s population had reached 85,050 in 5 sq mi (13 km), making it the most densely populated city in the Southern United States. In 1900 the Census Bureau reported Richmond’s population as 62.1% white and 37.9% black. Freed slaves and their descendants created a thriving African-American business community, and the city’s historic Jackson Ward became known as the “Wall Street of Black America”. In 1903 African-American businesswoman and financier Maggie L. Walker chartered St. Luke Penny Savings Bank and served as its first president. Charles Thaddeus Russell was Richmond’s first black architect and he designed the building for Walker. Walker was the first female bank president in the United States. Today the bank is called the Consolidated Bank and Trust Company and is the country’s oldest surviving African-American bank. Other figures from this time included John Mitchell Jr. In 1910 the former city of Manchester consolidated with Richmond, and in 1914 the city annexed Barton Heights, Ginter Park, and Highland Park in Henrico County. In May 1914 Richmond became the headquarters of the Fifth District of the Federal Reserve Bank.

Several major performing arts venues were constructed during the 1920s, including what are now the Landmark Theatre, Byrd Theatre, and Carpenter Theatre. The city’s first radio station, WRVA, began broadcasting in 1925. WTVR-TV (CBS 6), Richmond’s first television station, was the first TV station south of Washington, D.C.

Between 1963 and 1965 there was a “downtown boom” that led to the construction of more than 700 buildings. In 1968 Virginia Commonwealth University was created by the merger of the Medical College of Virginia with the Richmond Professional Institute. In 1970 Richmond’s borders expanded by an additional 27 sq mi (70 km) on the southside. After several years of court cases in which Chesterfield County fought annexation, more than 47,000 former Chesterfield County residents found themselves within the city’s perimeters on January 1, 1970. In 1996 still-sore tensions arose amid controversy involved in adding a statue of African American Richmond native and tennis star Arthur Ashe to the series of statues of Confederate generals on Monument Avenue. After several months of controversy Ashe’s bronze statue was finally completed, facing the opposite direction from the Confederate generals, on July 10, 1996.

A multimillion-dollar flood wall was completed in 1995 to protect low-lying areas of city from the oft-rising James River. As a result, the River District businesses grew rapidly, and today the area is home to much of Richmond’s entertainment, dining and nightlife activity, bolstered by the creation of a Canal Walk along the city’s former industrial canals.

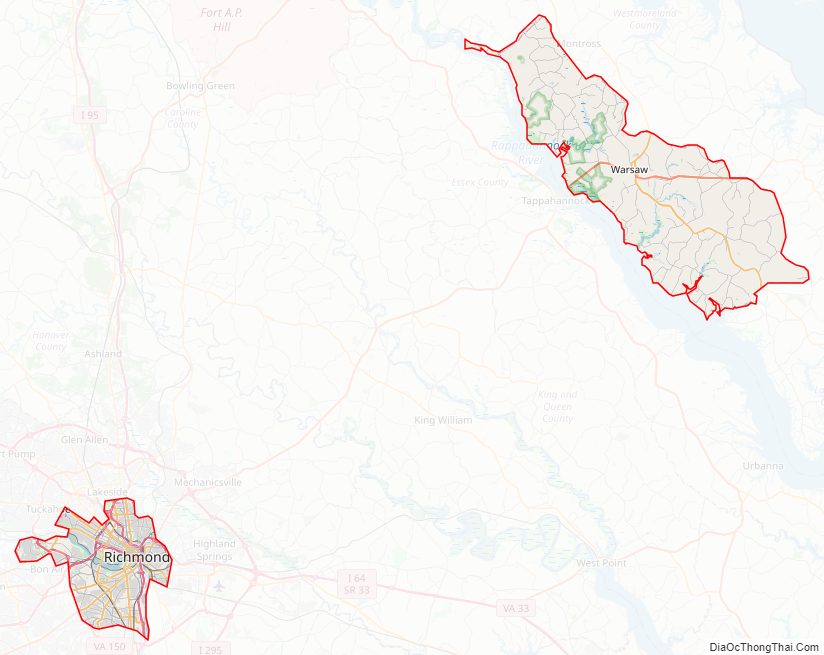

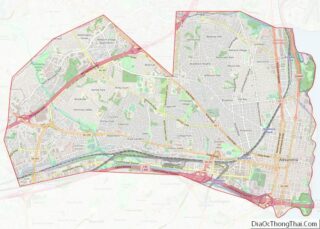

Richmond City Road Map

Geography

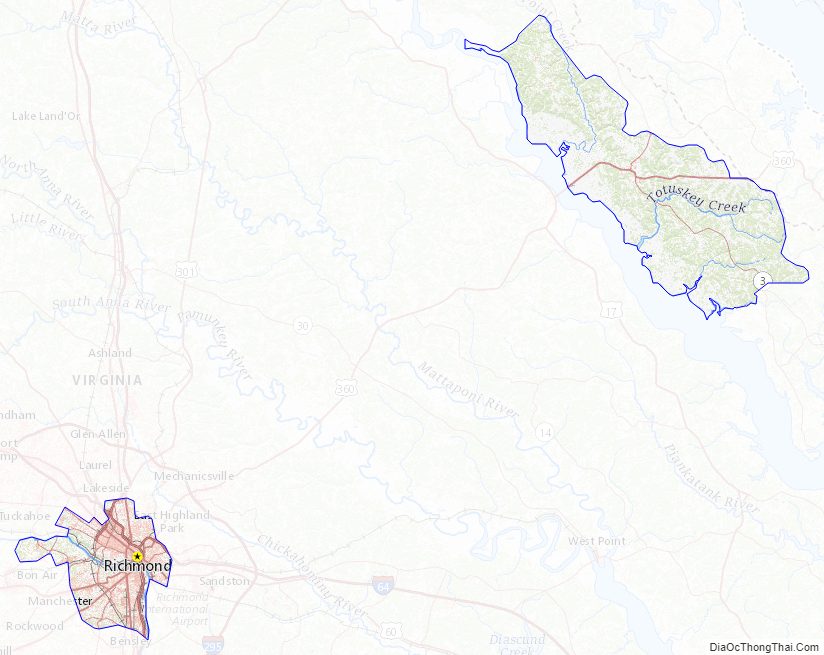

Richmond is located at 37°32′N 77°28′W / 37.533°N 77.467°W / 37.533; -77.467 (37.538, −77.462). According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 62 sq mi (160 km), of which 60 sq mi (160 km) is land and 2.7 sq mi (7.0 km) of it (4.3%) is water. The city is in the Piedmont region of Virginia, at the James River’s highest navigable point. The Piedmont region is characterized by relatively low, rolling hills, and lies between the low, flat Tidewater region and the Blue Ridge Mountains. Significant bodies of water in the region include the James River, the Appomattox River, and the Chickahominy River.

The Richmond-Petersburg Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), the 44th largest in the United States, includes the independent cities of Richmond, Colonial Heights, Hopewell, and Petersburg, as well as the counties of Charles City, Chesterfield, Dinwiddie, Goochland, Hanover, Henrico, New Kent, Powhatan, and Prince George. On July 1, 2009, the Richmond—Petersburg MSA’s population was 1,258,251.

Richmond is located 21.69 miles north of Petersburg, Virginia, 66.10 miles southeast of Charlottesville, Virginia, 79.24 miles northwest of Norfolk, Virginia, 96.87 miles south of Washington, D.C., and 138.72 miles northeast of Raleigh, North Carolina.

Cityscape

Richmond’s original street grid, laid out in 1737, included the area between what are now Broad, 17th, and 25th Streets and the James River. Modern Downtown Richmond is slightly farther west, on the slopes of Shockoe Hill. Nearby neighborhoods include Shockoe Bottom, the historically significant and low-lying area between Shockoe Hill and Church Hill, and Monroe Ward, which contains the Jefferson Hotel. Richmond’s East End includes neighborhoods like rapidly gentrifying Church Hill, home to St. John’s Church, as well as poorer areas like Fulton, Union Hill, and Fairmont, and public housing projects like Mosby Court, Whitcomb Court, Fairfield Court, and Creighton Court closer to Interstate 64.

The area between Belvidere Street, Interstate 195, Interstate 95, and the river, which includes Virginia Commonwealth University, is socioeconomically and architecturally diverse. North of Broad Street, the Carver and Newtowne West neighborhoods are demographically similar to neighboring Jackson Ward, with Carver experiencing some gentrification due to its proximity to VCU. The affluent area between the Boulevard, Main Street, Broad Street, and VCU, known as the Fan, is home to Monument Avenue, an outstanding collection of Victorian architecture, and many students. West of the Boulevard is the Museum District, which contains the Virginia Historical Society and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. South of the Downtown Expressway are Byrd Park, Maymont, Hollywood Cemetery, the predominantly black working-class Randolph neighborhood, and white working-class Oregon Hill. Cary Street between Interstate 195 and the Boulevard is a popular commercial area called Carytown.

Richmond’s Northside is home to numerous listed historic districts. Neighborhoods such as Chestnut Hill-Plateau and Barton Heights began to develop at the end of the 19th century when the new streetcar system made it possible for people to live on the outskirts of town and still commute to jobs downtown. Other prominent Northside neighborhoods include Azalea, Barton Heights, Bellevue, Chamberlayne, Ginter Park, Highland Park, and Rosedale.

Farther west is the affluent, suburban West End. Windsor Farms is among its best-known sections. The West End also includes middle- to low-income neighborhoods such as Laurel, Farmington and the areas surrounding the Regency Mall. More affluent areas include Glen Allen, Short Pump, and the areas of Tuckahoe away from Regency Mall, all north and northwest of the city. The University of Richmond and the Country Club of Virginia are located on this side of town near the Richmond-Henrico border.

The portion of the city south of the James River is known as the Southside. Southside neighborhoods range from the affluent and middle-class suburban Westover Hills, Forest Hill, Southampton, Stratford Hills, Oxford, Huguenot Hills, Hobby Hill, and Woodland Heights to the impoverished Manchester and Blackwell areas, the Hillside Court housing projects, and the ailing Jefferson Davis Highway commercial corridor. Other Southside neighborhoods include Fawnbrook, Broad Rock, Cherry Gardens, Cullenwood, and Beaufont Hills. Much of Southside developed a suburban character as part of Chesterfield County before being annexed by Richmond, most notably in 1970.

Climate

According to the Köppen climate classification, Richmond has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen: Cfa), with hot, humid summers and moderately cold winters. The Trewartha classification defines Richmond as Temperate Oceanic Climate due to winter chill. The mountains to the west act as a partial barrier to outbreaks of cold, continental air in winter; Arctic air is delayed long enough to be modified, then further warmed as it subsides in its approach to Richmond. The open waters of the Chesapeake Bay and Atlantic Ocean contribute to the humid summers and cool winters. The coldest weather normally occurs from late December to early February, and the January daily mean temperature is 37.9 °F (3.3 °C), with an average of 6.0 days with highs at or below the freezing mark. Richmond’s Downtown and areas south and east of downtown are in USDA Hardiness zones 7b. Surrounding suburbs and areas to the north and west of Downtown are in Hardiness Zone 7a. Temperatures seldom fall below 0 °F (−18 °C), with the most recent subzero reading on January 7, 2018, when the temperature reached −3 °F (−19 °C). The July daily mean temperature is 79.3 °F (26.3 °C), and high temperatures reach or exceed 90 °F (32 °C) approximately 43 days a year; 100 °F (38 °C) temperatures are not uncommon but do not occur every year. Extremes in temperature have ranged from −12 °F (−24 °C) on January 19, 1940, up to 107 °F (42 °C) on August 6, 1918. The record cold maximum is 11 °F (−12 °C), set on February 11 and 12, 1899. The record warm minimum is 81 °F (27 °C), set on July 12, 2011.

Precipitation is rather uniformly distributed throughout the year. Dry periods lasting several weeks sometimes occur, especially in autumn, when long periods of pleasant, mild weather are most common. There is considerable variability in total monthly amounts from year to year so that no one month can be depended upon to be normal. Snow has been recorded during seven of the 12 months. Falls of 4 in (10 cm) or more within 24 hours occur once a year on average. Annual snowfall is usually moderate, averaging 10.5 in (27 cm) per season. Snow typically remains on the ground for only one or two days, but remained for 16 days in 2010 (January 30 to February 14). Ice storms (freezing rain or glaze) are not uncommon, but are seldom severe enough to do considerable damage.

The James River reaches tidewater at Richmond, where flooding may occur in any month of the year, most frequently in March and least in July. Hurricanes and tropical storms have been responsible for most of the flooding during the summer and early fall months. Hurricanes passing near Richmond have produced record rainfalls. In 1955, three hurricanes brought record rainfall to Richmond within a six-week period. The most noteworthy were Hurricane Connie and Hurricane Diane, which brought heavy rains five days apart. In 2004, the downtown area suffered extensive flood damage after the remnants of Hurricane Gaston dumped up to 12 in (300 mm) of rain.

Damaging storms occur mainly from snow and freezing rain in winter, and from hurricanes, tornadoes, and severe thunderstorms in other seasons. Damage may be from wind, flooding, rain, or any combination of these. Tornadoes are infrequent but some notable ones have been observed in the Richmond area.

Downtown Richmond averages 84 days of nighttime frost annually. Nighttime frost is more common in areas north and west of Downtown and less common south and east of downtown. From 1981 to 2010 the average first temperature at or below freezing was on October 30 and the average last one on April 10.