Mystic is a village and census-designated place (CDP) in Groton and Stonington, Connecticut.

Historically, Mystic was a significant Connecticut seaport with more than 600 ships built over 135 years starting in 1784. Mystic Seaport, one of the largest maritime museums in the United States, has preserved a number of sailing ships, such as the whaling ship Charles W. Morgan. The village is located on the Mystic River, which flows into Fishers Island Sound and, by extension, Long Island Sound and the Atlantic Ocean. The Mystic River Bascule Bridge crosses the river in the center of the village. The name “Mystic” is derived from the Pequot term “missi-tuk” describing a large river whose waters are driven into waves by tides or wind. The population was 4,205 at the 2010 census.

| Name: | Mystic CDP |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 57 |

| LSAD Description: | CDP (suffix) |

| State: | Connecticut |

| County: | New London County |

| Elevation: | 10 ft (3 m) |

| Total Area: | 3.8 sq mi (9.8 km²) |

| Land Area: | 3.4 sq mi (8.7 km²) |

| Water Area: | 0.4 sq mi (1.1 km²) |

| Total Population: | 4,205 |

| Population Density: | 1,100/sq mi (430/km²) |

| ZIP code: | 06355, 06372, 06388 |

| Area code: | 860 |

| FIPS code: | 0949810 |

| Website: | mystic.org |

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

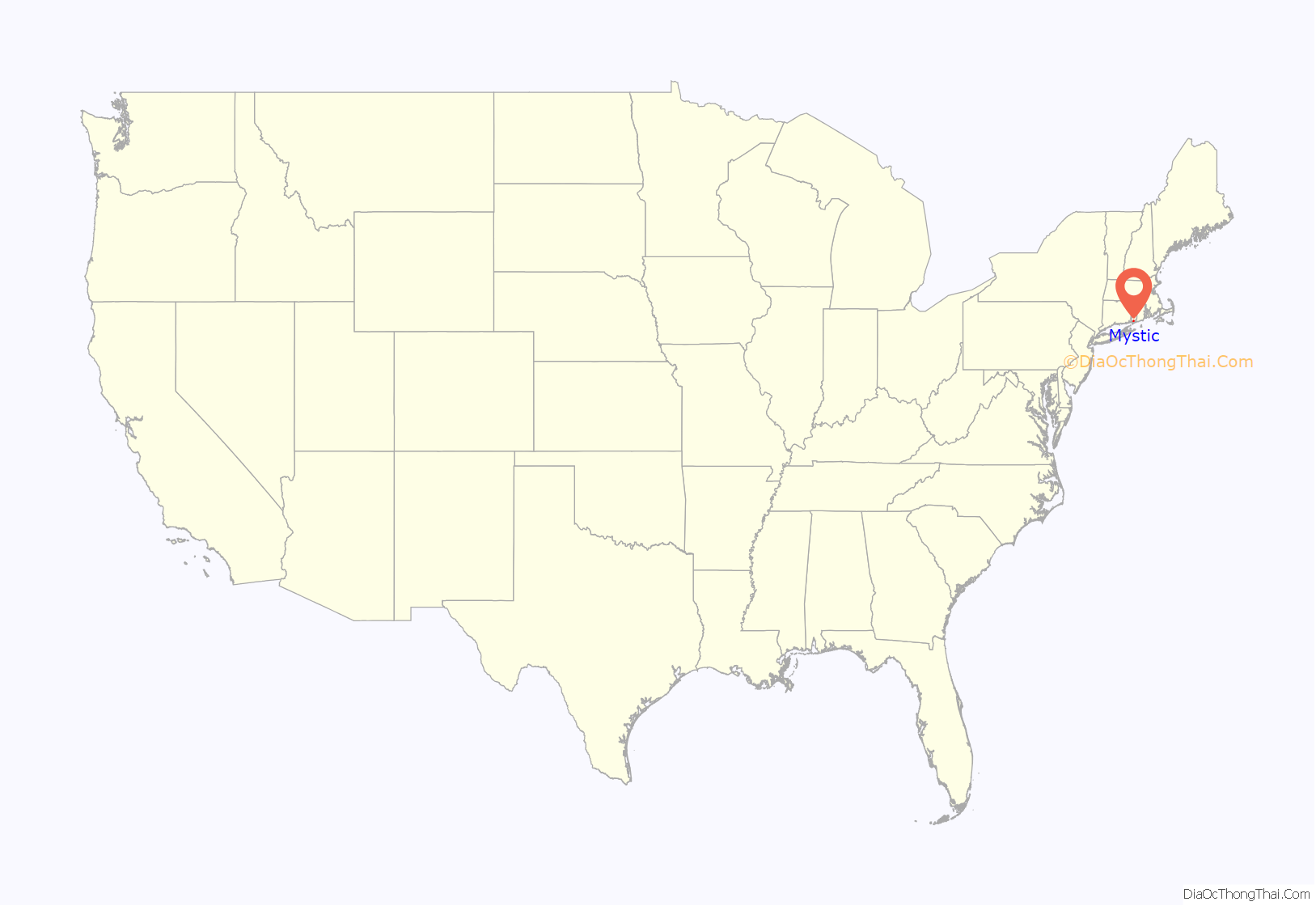

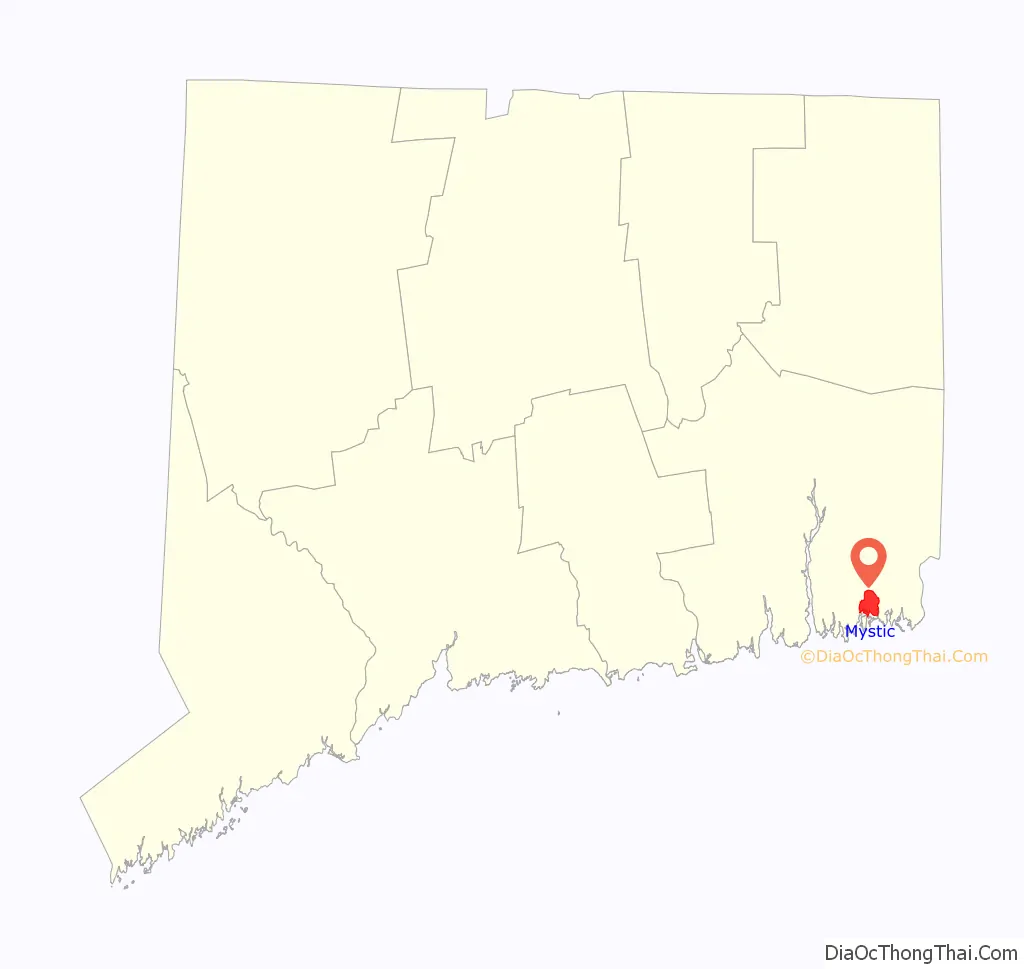

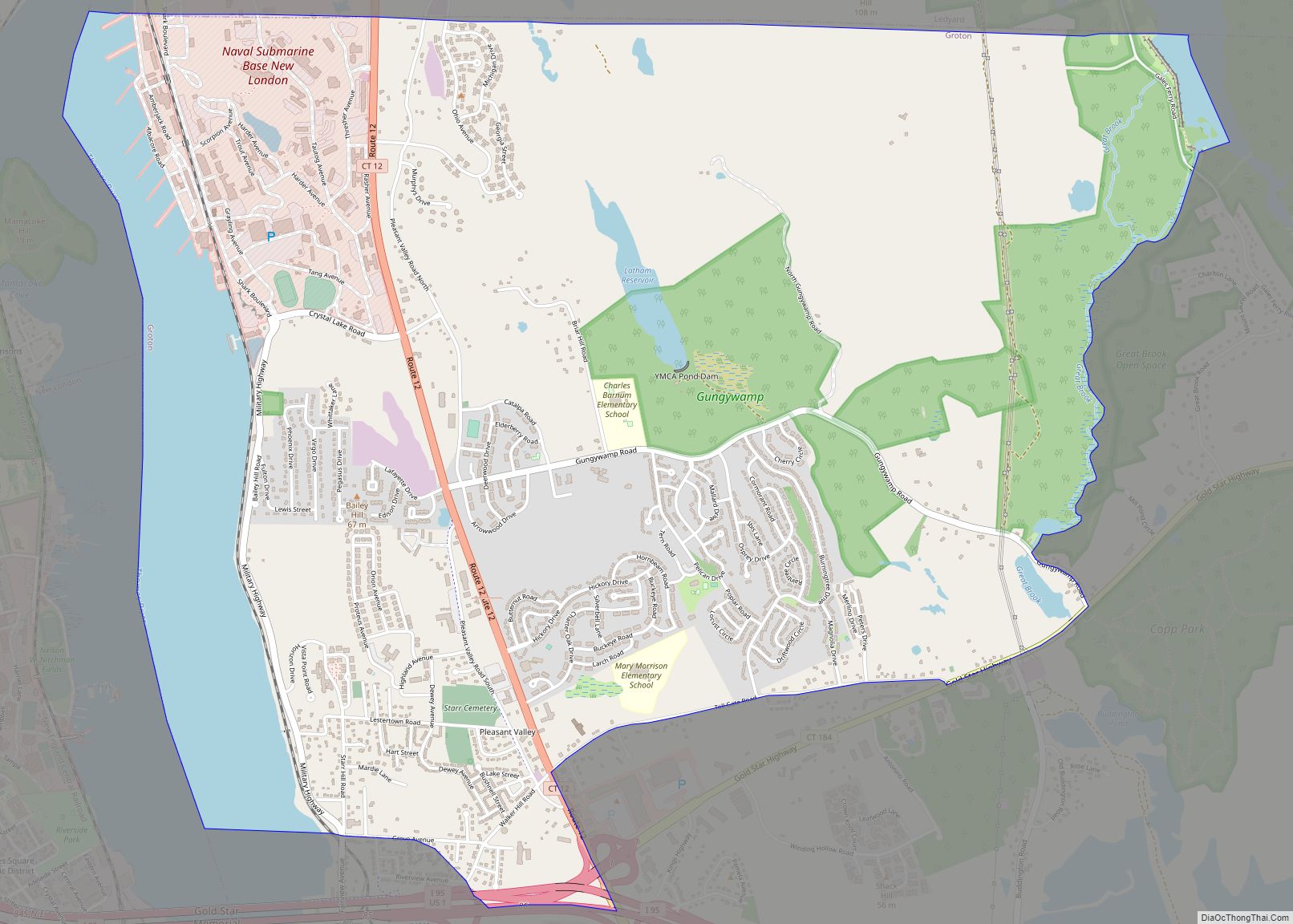

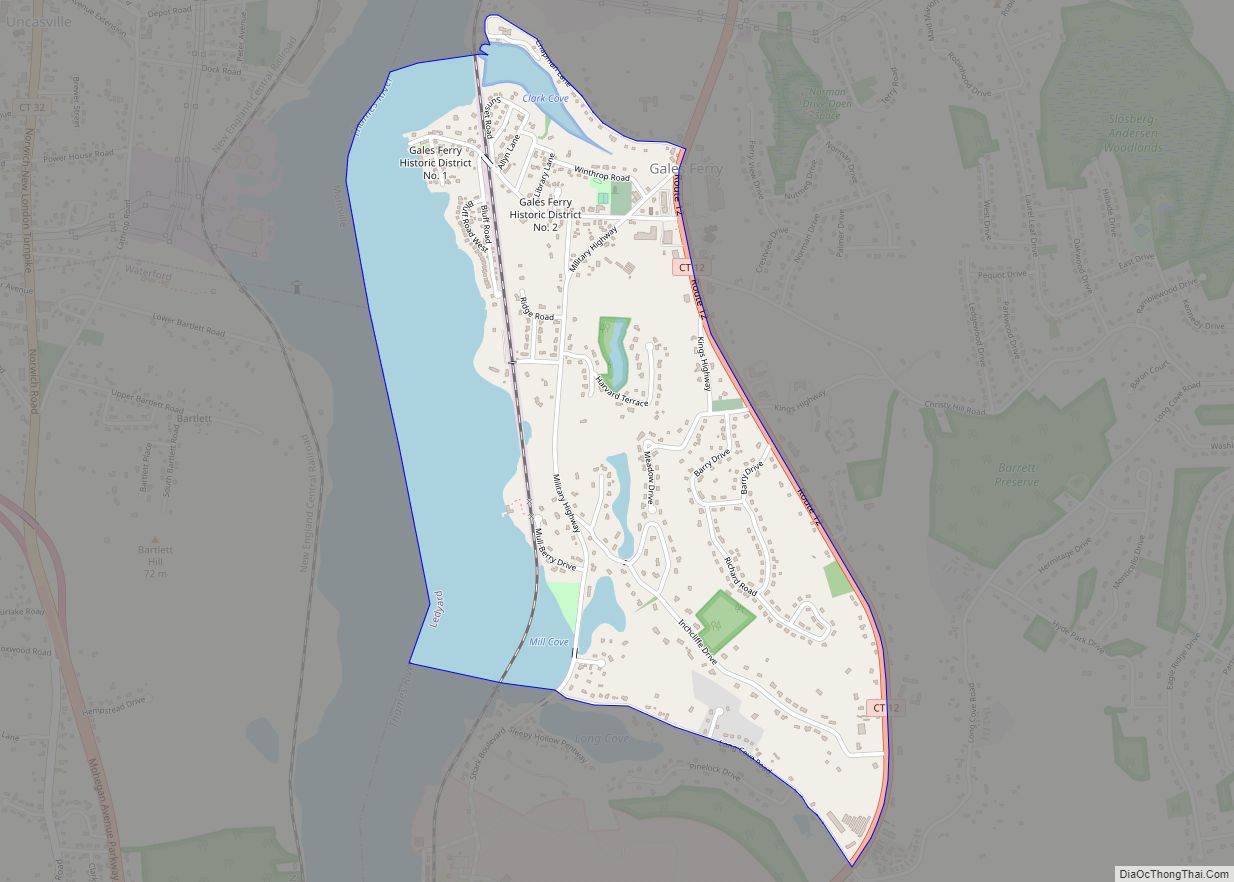

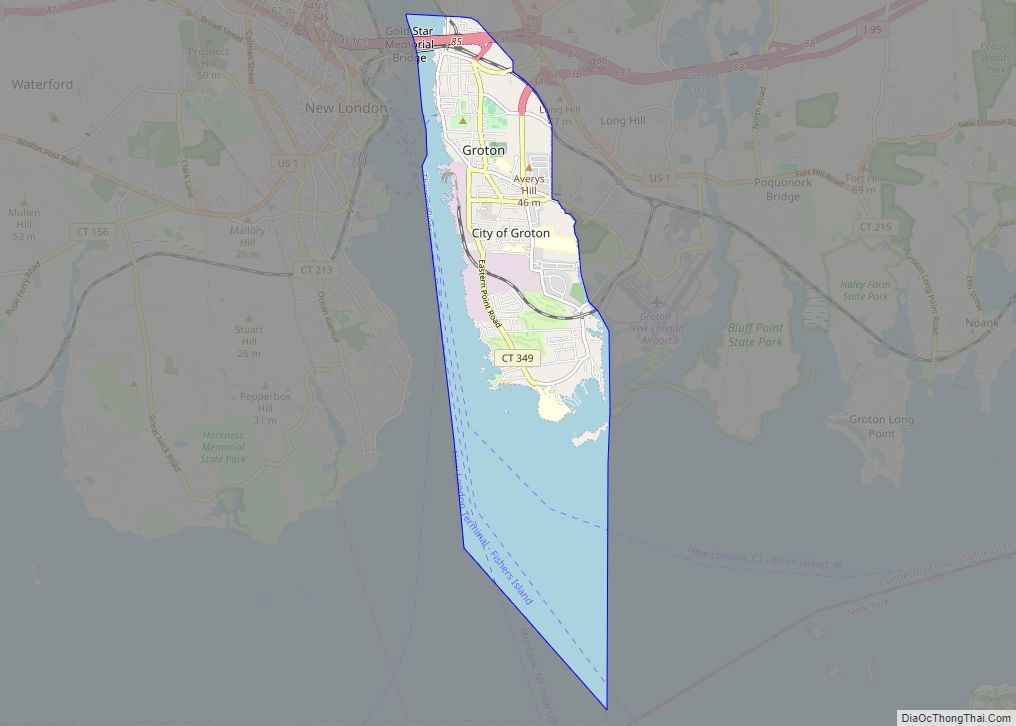

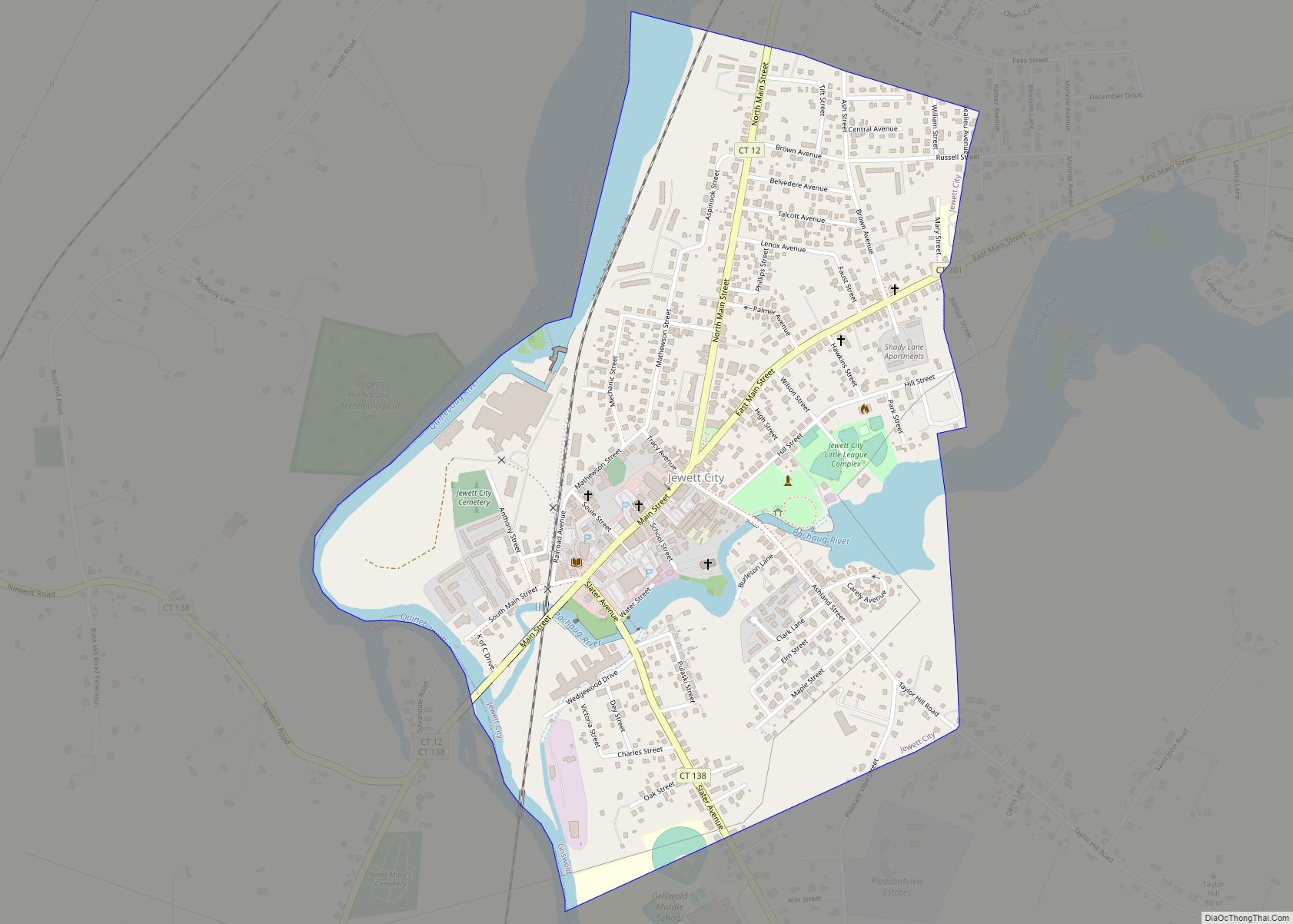

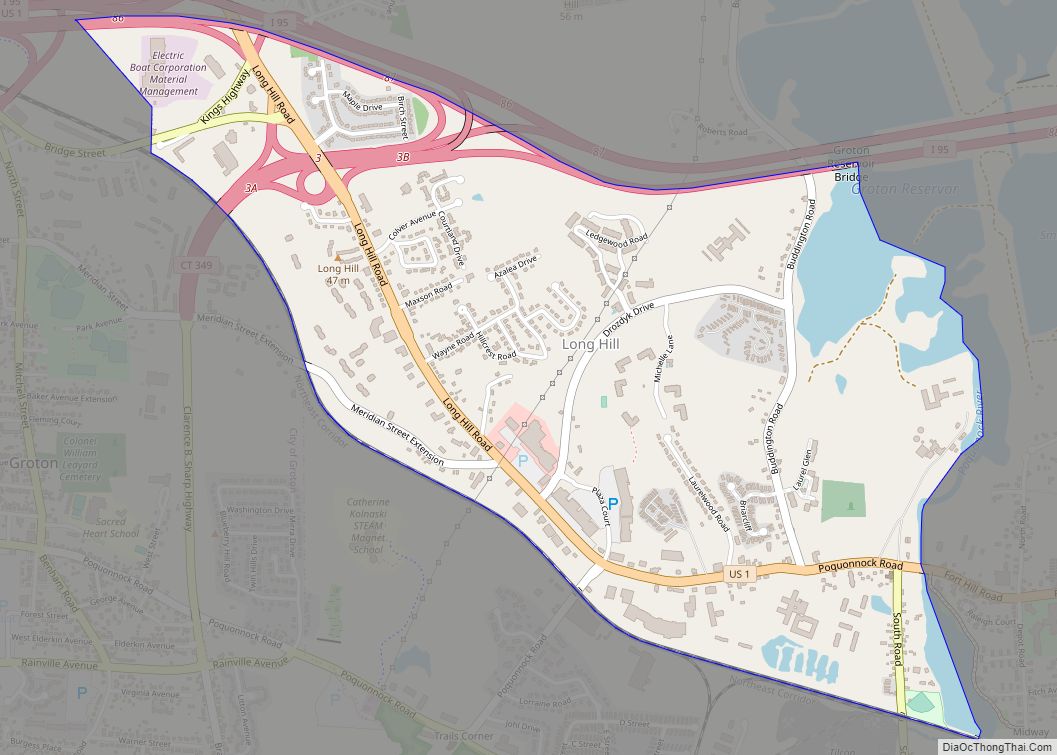

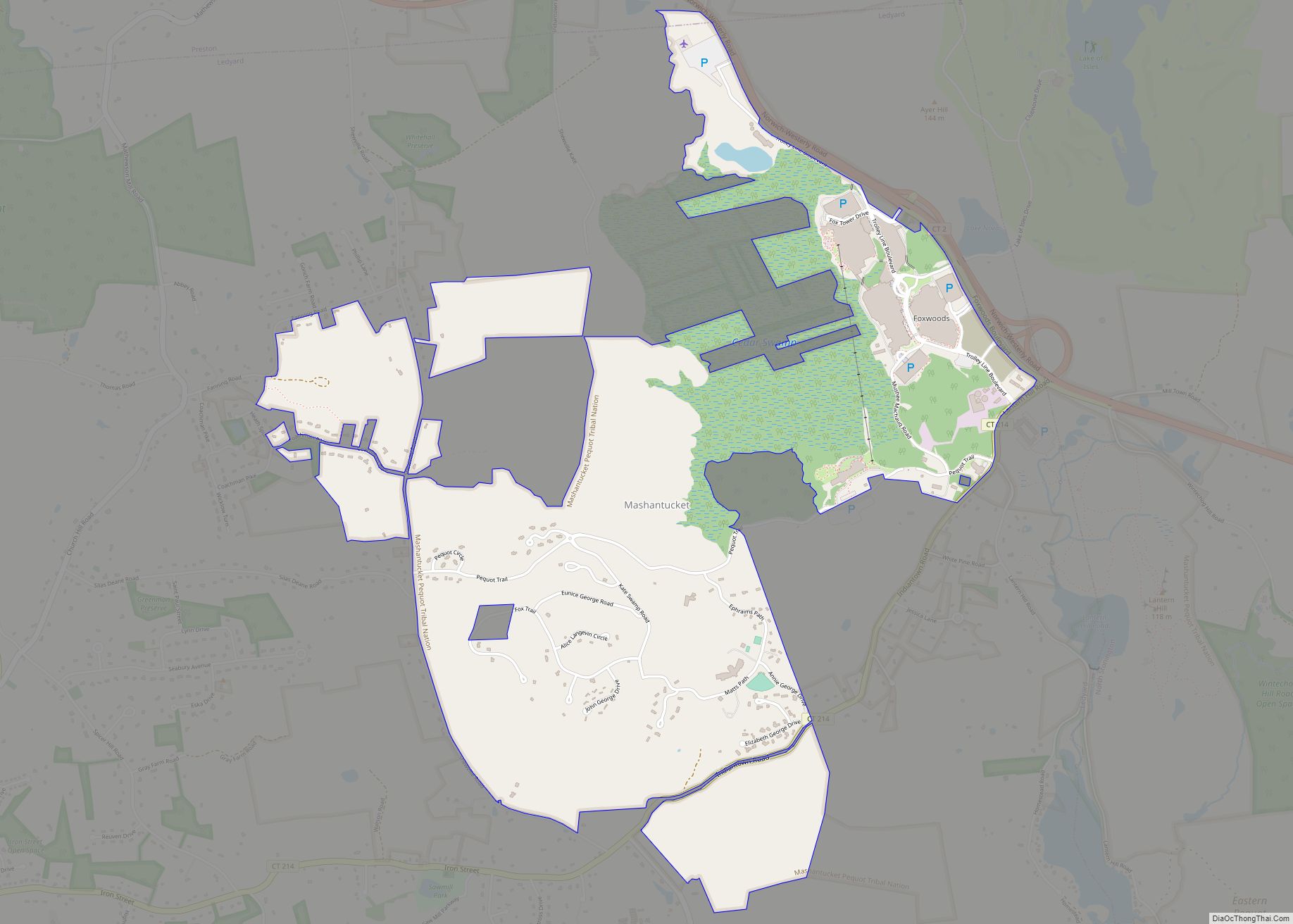

Mystic location map. Where is Mystic CDP?

History

Before the 17th century, the Pequot people lived in this portion of southeastern Connecticut. They were in control of a considerable amount of territory, extending toward the Pawcatuck River to the east and the Connecticut River to the west.

To the northwest, the Five Nations of the Iroquois dominated the land linked by the Great Lakes and the Hudson River, allowing trading to occur between the Iroquois and the Dutch. The Pequots were settled just distant enough to be secure from any danger that the Iroquois posed. The Pequot War profoundly affected the Mystic area between 1636 and 1638. In May 1637, captains John Underhill and John Mason led a mission through Narragansett land, along with their allies the Narragansetts and Mohegans, and struck the Pequot Indian settlement in Mystic in the event which came to be known as the Mystic massacre. On September 21, 1638, the colonists signed the Treaty of Hartford, officially ending the Pequot War.

English settlement

As a result of the Pequot War, Pequot control of the Mystic area ended and English settlements increased in the area. By the 1640s, Connecticut Colony began to grant land to the Pequot War veterans. John Winthrop the Younger, the son of the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, was among those to receive property, much of which was in southeastern Connecticut. Other early settlers in the Mystic area included Robert Burrows and George Denison, who held land in the Mystic River Valley.

Settlement grew slowly. The Connecticut government and Massachusetts Bay government began to quarrel over boundaries, thus causing some conflicting claims concerning governmental authority between the Mystic River and the Pawcatuck River. In the 1640s and 1650s, “Connecticut” referred to settlements located along the Connecticut River, as well as its claims in other parts of the region. Massachusetts Bay, however, claimed to have authority over Stonington and even into Rhode Island.

Connecticut did not have a royal charter that separated it from the Massachusetts Bay Colony; the Connecticut General Court was formed by leaders of the settlements. The General Court claimed rule of the area by right of conquest, but the Massachusetts Bay Colony saw matters differently. The Bay Colony had contributed to the war by sending a militia under captains John Underhill and Thomas Stoughton, which they argued gave territorial rights and authority to the Massachusetts Bay Colony rather than the Connecticut Court.

Both colonies turned to the United Colonies of New England to resolve the dispute. The United Colonies of New England was formed in 1643, established to settle disputes such as this one. They voted to establish the boundary between the claims of Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut at the Thames River. As a result, Connecticut would be positioned west of the river, and Massachusetts Bay could have the land to the east, including the Mystic River.

Throughout the next decade, colonists were beginning to settle around the Mystic River. John Mason, one of the captains who led the colonists against the Pequots, had previously been granted 500 acres (2 km) on the eastern banks of the Mystic River. He also received the island that now bears his name, though he never lived on the property. In 1653, John Gallup, Jr. was given 300 acres (1.2 km) approximately midway up the east part of the Mystic River.

Within the same year, others joined John Gallup and began to settle around the Mystic River. George Denison, a veteran of Oliver Cromwell’s army, was given his own strip of 300 acres (1.2 km) just south of Gallup’s land in 1654. Thomas Miner had immigrated to Massachusetts with John Winthrop and was granted many land plots, the main one lying on Quiambaug Cove, just east of the Mystic River. Other families granted land were Reverend Robert Blinman, the Beebe brothers, Thomas Parke, and Connecticut Governor John Hayne.

Like Captain John Mason, not all these men actually lived on their land. Many sold it to profit from or employed an overseer to cultivate their property. Many men, however, actually brought their wives and children, which indicated their plans on forming a community in the Mystic River Valley.

There was one recorded case of a woman who did not come to the Mystic River Valley as a wife. Widow Margaret Lake received a grant from the Massachusetts Bay authority and was the only woman to receive a land grant in her own name. She also did not live on her land but hired other people to maintain it. She took up residence in Lakes Pond. Her daughter was married to John Gallup, while her sister was married to Massachusetts Bay Governor John Winthrop.

By 1675, settlement had grown tremendously in the Mystic River Valley, and infrastructure was beginning to appear as well as an economy. The Pequot Trail was used as a main highway to get around the Mystic River and played a vital role in the settlers’ lives, allowing them to transport livestock, crops, furs, and other equipment to and from their farm lands. However, those families living on the east side of the Mystic River were unable to make any use of the Pequot Trail. As early as 1660, Robert Burrows was authorized to institute a ferry somewhere along the middle of the river’s length. This earned his home the name of “Half-way House”.

The Pequot Trail also connected the settlers to their church. Stonington residents found it difficult to attend church in Mystic or Groton, and this led to the creation of their own church. The town of Stonington was then established as separate from Mystic in regards to church attendance and was granted leave to build a church of their own. The building became known as the Road Church.

Colonists began public schools in this area around 1679, and John Fish became the first schoolmaster in Stonington, conducting classes and lessons in his home. Education was a very important thing to the New England colonists, enabling children and servants to learn literacy skills. Most families throughout New England had six or more children in each household, giving Fish plenty of students.

Fish also gave lectures and insights about marriage and maintenance of a solid family. Divorce was very uncommon in those days; however, John Fish’s wife ran off with Samuel Culver. In the case of a runaway spouse, the abandoned spouse was not allowed to file for divorce until six years had passed. This law ensured that the spouse was actually gone and not intending to come back. Fish was eventually allowed to divorce in 1680, but this had no impact on his reputation as a school teacher, and parents continued to allow their children to attend his classes.

18th century

By the first decade of the 18th century, three villages had begun to develop along the Mystic River. The largest village was called Mystic (now Old Mystic), also known as the Head of the River because it lay where several creeks united into the Mystic River estuary. Two villages lay farther down the river. One was called Stonington and was considered to be Lower Mystic, consisting of twelve houses by the early 19th century. These twelve houses lay along Willow Street, which ended at the ferry landing. This is now the Stonington side of the village of Mystic. On the opposite bank of the river in the town of Groton stood the village that became known as Portersville. This is the Groton side of the village of Mystic.

National Register of Historic Places

Mystic has three historic districts: the Mystic Bridge Historic District around U.S. Route 1 and Route 27, Rossie Velvet Mill Historic District between Pleasant Street and Bruggerman Place, and the Mystic River Historic District around U.S. Route 1 and Route 215. Other historic sites in Mystic are:

- Joseph Conrad (ship) at Mystic Seaport Museum

- Charles W. Morgan (ship) at Mystic Seaport Museum

- Emma C. Berry (sloop) at Mystic Seaport Museum

- L. A. Dunton (schooner) at Mystic Seaport Museum

- Pequotsepos Manor on Pequotsepos Road

- Sabino (steamer) at Mystic Seaport Museum

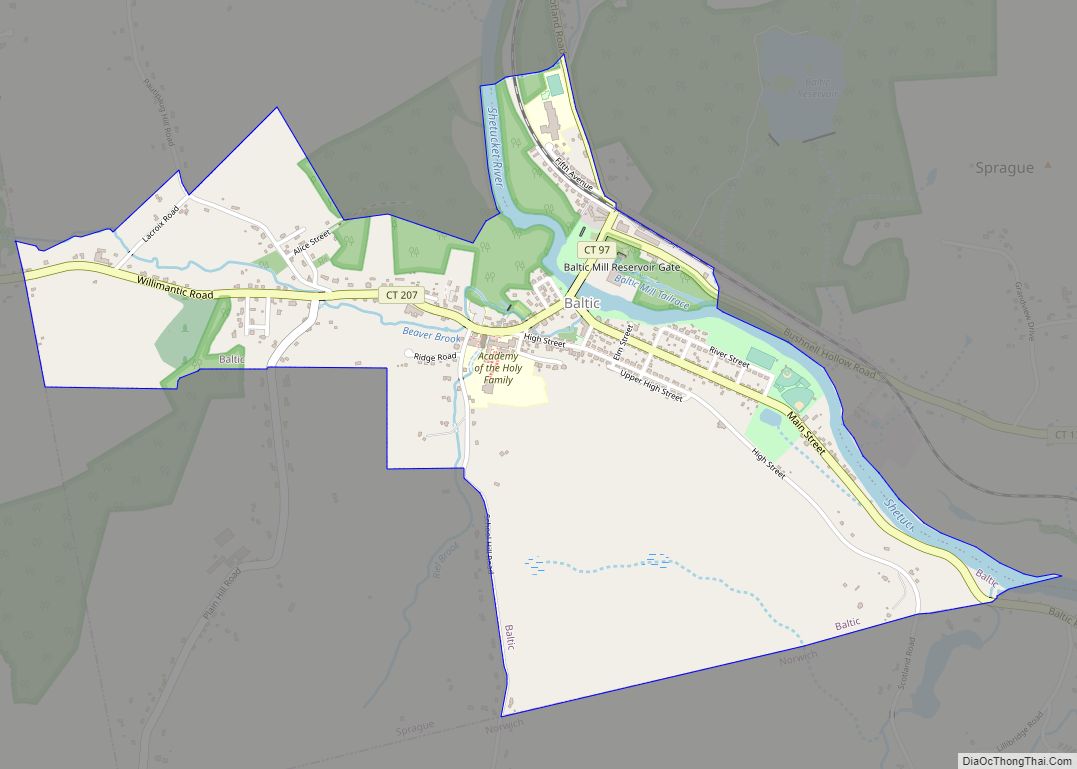

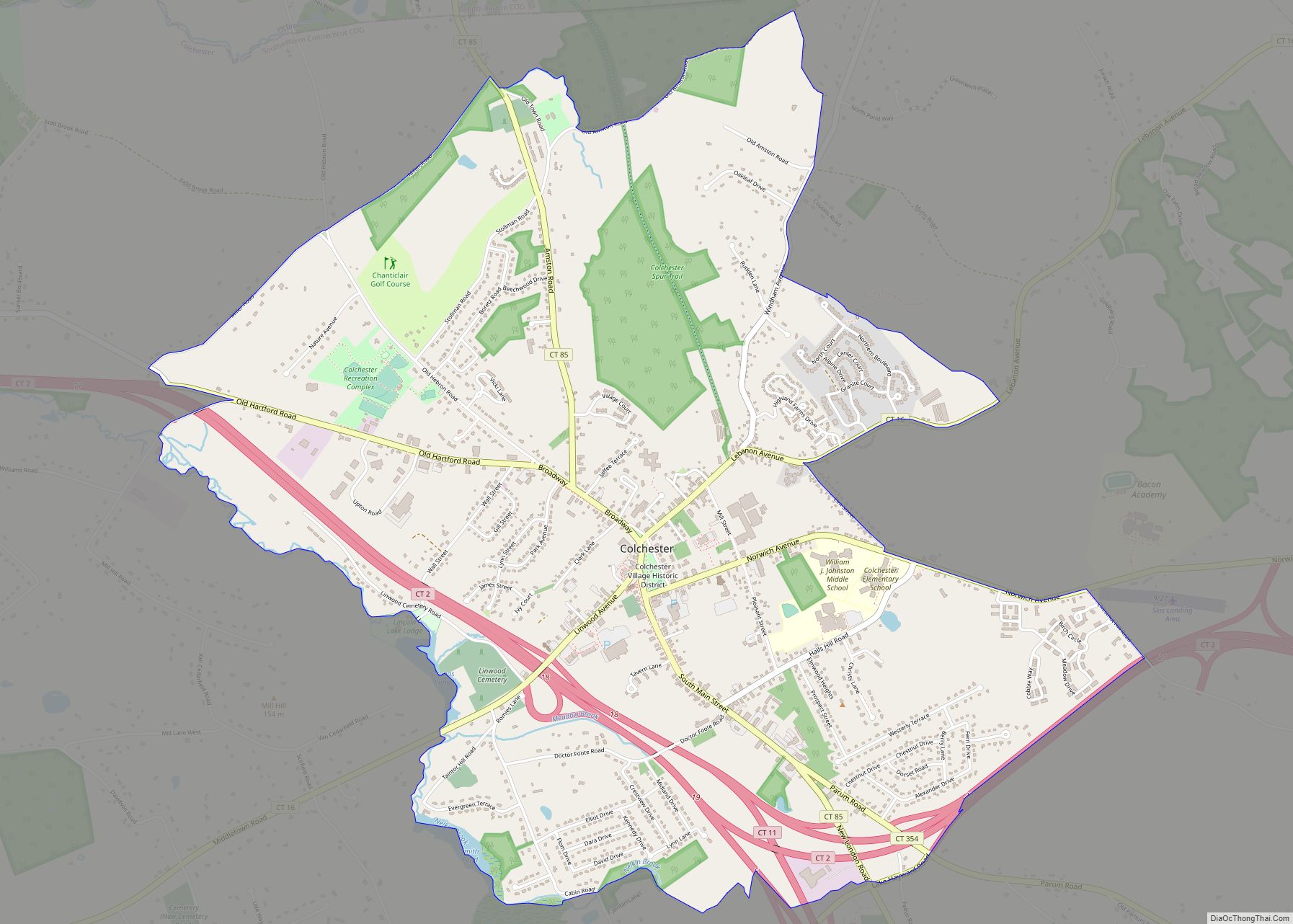

Mystic Road Map

Mystic city Satellite Map

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 3.8 square miles (9.8 km), of which 3.3 square miles (8.5 km) is land and 0.4 square miles (1.0 km), or 11.61%, is water. The village is on the east and west bank of the estuary of the Mystic River. Mason’s Island (Pequot language: Chippachaug) fills the south end of the estuary. Most of the bedrock of Mystic is “gneissic, crystalline terrane extending from eastern Massachusetts through western Rhode Island and across southeastern Connecticut north of Long Island Sound,” according to geologist Richard Goldsmith.

See also

Map of Connecticut State and its subdivision: Map of other states:- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming