Bangor (/ˈbæŋɡɔːr/ BANG-gor) is a city in and the county seat of Penobscot County, Maine, United States. The city proper has a population of 31,753, making it the state’s third-largest settlement, behind Portland (68,408) and Lewiston (37,121). Bangor is known as the “Queen City.”

Modern Bangor was established in the mid-19th century with the lumber and shipbuilding industries. Lying on the Penobscot River, logs could be floated downstream from the Maine North Woods and processed at the city’s water-powered sawmills, then shipped from Bangor’s port to the Atlantic Ocean 30 miles (48 km) downstream, and from there to any port in the world. Evidence of this is still visible in the lumber barons’ elaborate Greek Revival and Victorian mansions and the 31-foot-high (9.4 m) statue of Paul Bunyan. Today, Bangor’s economy is based on services and retail, healthcare, and education.

Bangor has a port of entry at Bangor International Airport, also home to the Bangor Air National Guard Base. Historically Bangor was an important stopover on the Great Circle Air Route between the U.S. East Coast and Europe.

Bangor has a humid continental climate, with cold, snowy winters, and warm summers.

| Name: | Bangor city |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 25 |

| LSAD Description: | city (suffix) |

| State: | Maine |

| County: | Penobscot County |

| Elevation: | 118 ft (36 m) |

| Land Area: | 34.26 sq mi (88.73 km²) |

| Water Area: | 0.34 sq mi (0.87 km²) |

| Population Density: | 926.85/sq mi (357.86/km²) |

| Area code: | 207 |

| FIPS code: | 2302795 |

| GNISfeature ID: | 0561558 |

| Website: | BangorMaine.gov |

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

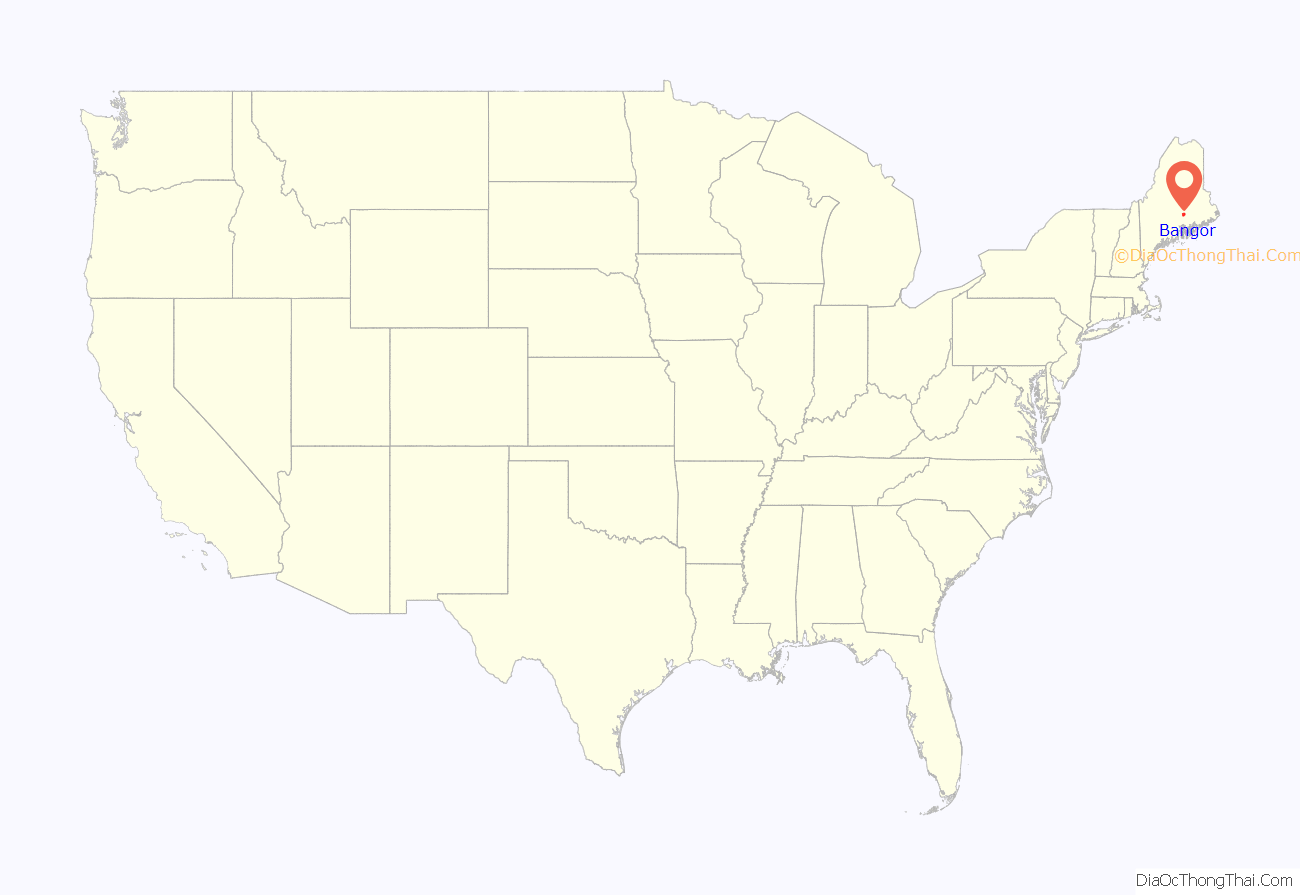

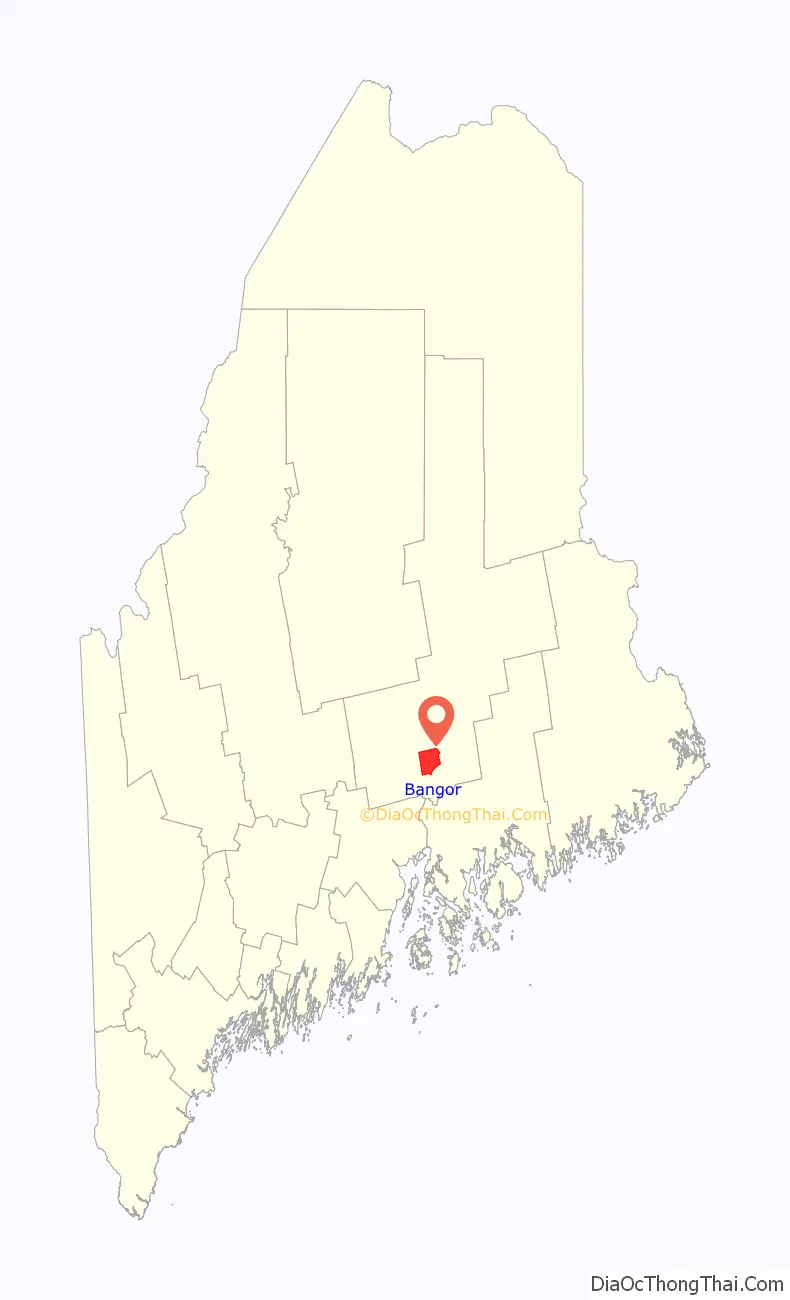

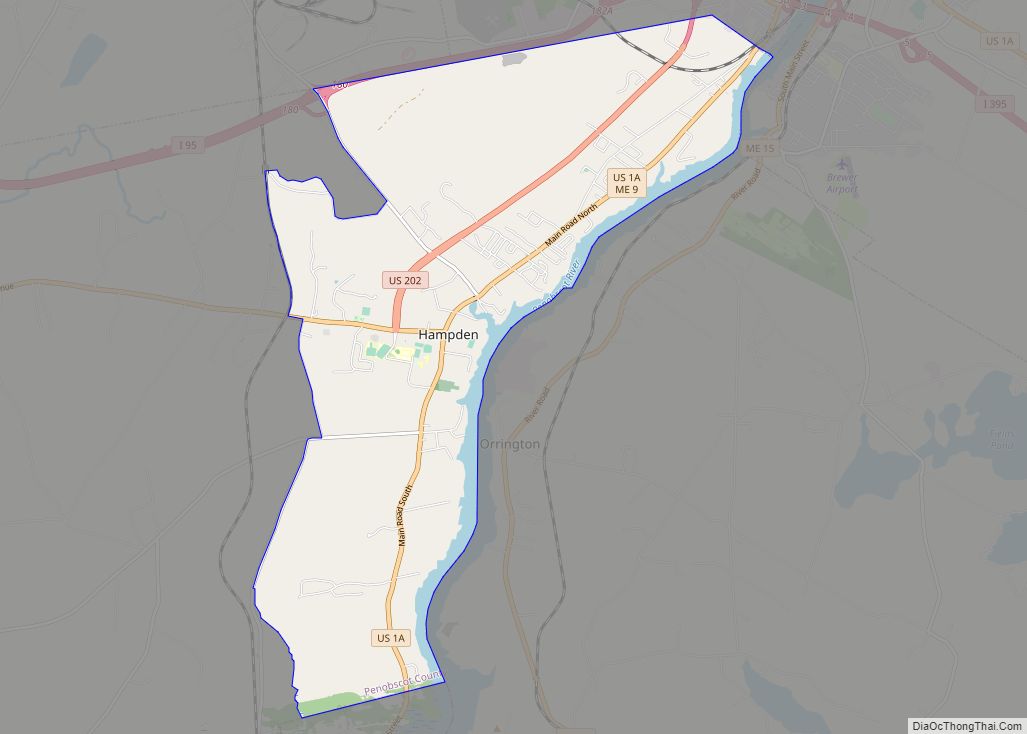

Bangor location map. Where is Bangor city?

History

European settlement

The Penobscot people have inhabited the area around present-day Bangor for at least 11,000 years and still occupy tribal land on the nearby Penobscot Indian Island Reservation. They practised some agriculture, but less than peoples in southern New England where the climate is milder, and subsisted on what they could hunt and gather. Contact with Europeans was not uncommon during the 1500s because the fur trade was lucrative and the Penobscot were willing to trade pelts for European goods. The first European known to have explored the area in 1524 was Estêvão Gomes, a Portuguese navigator who sailed in the service of Spain in the 1520s. The Spaniards, led by Gómez, were the first Europeans to make landfall in what is now Maine, followed by the Frenchman Samuel de Champlain in 1605. The Jesuits established a mission on Penobscot Bay in 1609, which was then part of the French colony of Acadia, and the valley remained contested between France and Britain into the 1750s, making it one of the last regions to become part of New England.

In 1769, Jacob Buswell founded a settlement at the site. Then known as Norumbega, by 1772, there were 12 families, along with a sawmill, store, and school. By 1787, the population was 567. It was known as Sunbury until incorporation as Bangor in 1791.

Wars of Independence, 1812, and Civil War

In 1779, the rebel Penobscot Expedition fled up the Penobscot River and ten of its ships were scuttled by the British fleet at Bangor. The ships remained there until the late 1950s, when construction of the Joshua Chamberlain Bridge disturbed the site. Six cannons were removed from the riverbed, five of which are on display throughout the region (one was thrown back into the river by area residents angered that the archeological site was destroyed for the bridge’s construction).

During the War of 1812 Bangor and Hampden were sacked by the British.

Maine was part of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts until 1820 when it voted to secede from Massachusetts and was admitted to the Union as the 23rd state under the Missouri Compromise.

In 1861, a mob ransacked the offices of the Democratic newspaper the Bangor Daily Union, threw the presses and other materials into the street and burned them. Editor Marcellus Emery escaped unharmed and it was only after the war that he resumed publishing.

During the American Civil War the locally mustered 2nd Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment was the first to march out of Maine in 1861, and played a prominent part in the First Battle of Bull Run. The 1st Maine Heavy Artillery Regiment, mustered in Bangor and commanded by a local merchant, lost more men than any other Union regiment in the war (especially in the Second Battle of Petersburg, 1864). The 20th Maine Infantry Regiment held Little Round Top in the Battle of Gettysburg. A bridge connecting Bangor with Brewer is named for Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, the regiment’s leader and one of eight Civil War soldiers from Penobscot County towns to receive the Medal of Honor. Bangor’s Charles A. Boutelle accepted the surrender of the Confederate fleet after the Battle of Mobile Bay. A Bangor residential street is named for him. The Confederate States Navy captured several Bangor ships during the Civil War.

Bangor was near the lands disputed during the Aroostook War, a boundary dispute with Britain in 1838–1839. The passion of the Aroostook War signaled the increasing role lumbering and logging played in the Maine economy, particularly in the state’s central and eastern sections. Bangor arose as a lumbering boom-town in the 1830s, and a potential demographic and political rival to Portland. Bangor became for a time the largest lumber port in the world, and the site of furious land speculation that extended up the Penobscot River valley and beyond.

Industrialization: lumbering, shipping, and manufacturing

The Penobscot River drainage basin above Bangor was unattractive to settlement for farming, but well suited to lumbering. Winter snow allowed logs to be dragged from the woods by horse-teams. Carried to the Penobscot or its tributaries, log driving in the snowmelt brought them to waterfall-powered sawmills upriver from Bangor. The sawed lumber was then shipped from the city’s docks, Bangor being at the head-of-tide (between the rapids and the ocean) to points anywhere in the world. Shipbuilding was also developed. Bangor capitalists also owned most of the forests. The main markets for Bangor lumber were the East Coast cities. Much was also shipped to the Caribbean and to California during the Gold Rush, via Cape Horn, before sawmills could be established in the west. Bangorians later helped transplant the Maine culture of lumbering to the Pacific Northwest, and participated directly in the Gold Rush. Bangor, Washington; Bangor, California; and Little Bangor, Nevada, are legacies of this contact.

By 1860, Bangor was the world’s largest lumber port, with 150 sawmills operating along the river. The city shipped over 150 million boardfeet of lumber a year, much of it in Bangor-built and Bangor-owned ships. In the year 1860, 3,300 lumbering ships passed by the docks.

Many of the lumber barons built elaborate Greek Revival and Victorian houses that still stand in the Broadway Historic District. Bangor has many substantial old churches, and shade trees. The city was so beautiful it was called “The Queen City of the East”. The shorter Queen City appellation is still used by some local clubs, organizations, events and businesses.

In addition to shipping lumber, 19th-century Bangor was the leading producer of moccasins, shipping over 100,000 pairs a year by the 1880s. Exports also included bricks, leather, and even ice (which was cut and stored in winter, then shipped to Boston, and even China, the West Indies and South America).

Bangor had certain disadvantages compared to other East Coast ports, including its rival Portland, Maine. Being on a northern river, its port froze during the winter, and it could not take the largest ocean-going ships. The comparative lack of settlement in the forested hinterland also gave it a comparatively small home market.

In 1844 the first ocean-going iron-hulled steamship in the U.S. was named The Bangor. She was built by the Harlan and Hollingsworth firm of Wilmington, Delaware in 1844, and was intended to take passengers between Bangor and Boston. On her second voyage, however, in 1845, she burned to the waterline off Castine. She was rebuilt at Bath, returned briefly to her earlier route, but was soon purchased by the U.S. government for use in the Mexican–American War.

Modern Bangor

Bangor continued to prosper as the pulp and paper industry replaced lumbering, and railroads replaced shipping. Local capitalists also invested in a train route to Aroostook County in northern Maine (the Bangor and Aroostook Railroad), opening that area to settlement.

Bangor’s Hinkley & Egery Ironworks (later Union Ironworks) was a local center for invention in the 19th and early 20th centuries. A new type of steam engine built there, named the “Endeavor”, won a gold medal at the New York Crystal Palace Exhibition of the American Institute in 1856. The firm won a diploma for a shingle-making machine the following year. In the 1920s, Union Iron Works engineer Don A. Sargent invented the first automotive snow plow. Sargent patented the device and the firm manufactured it for a national market.

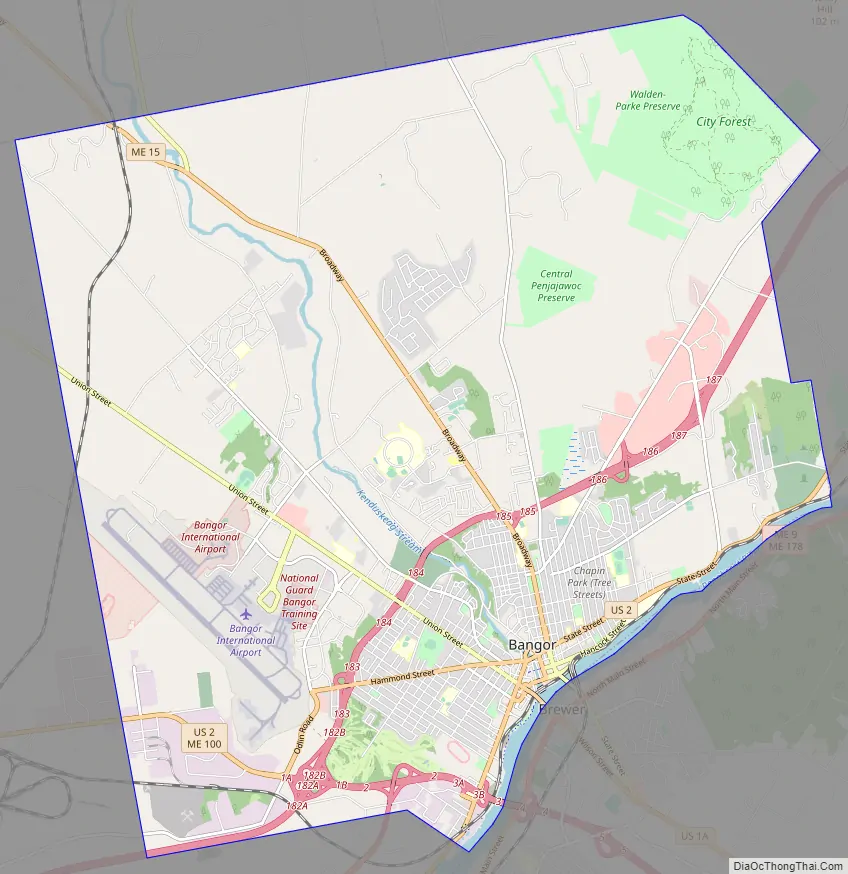

Bangor Road Map

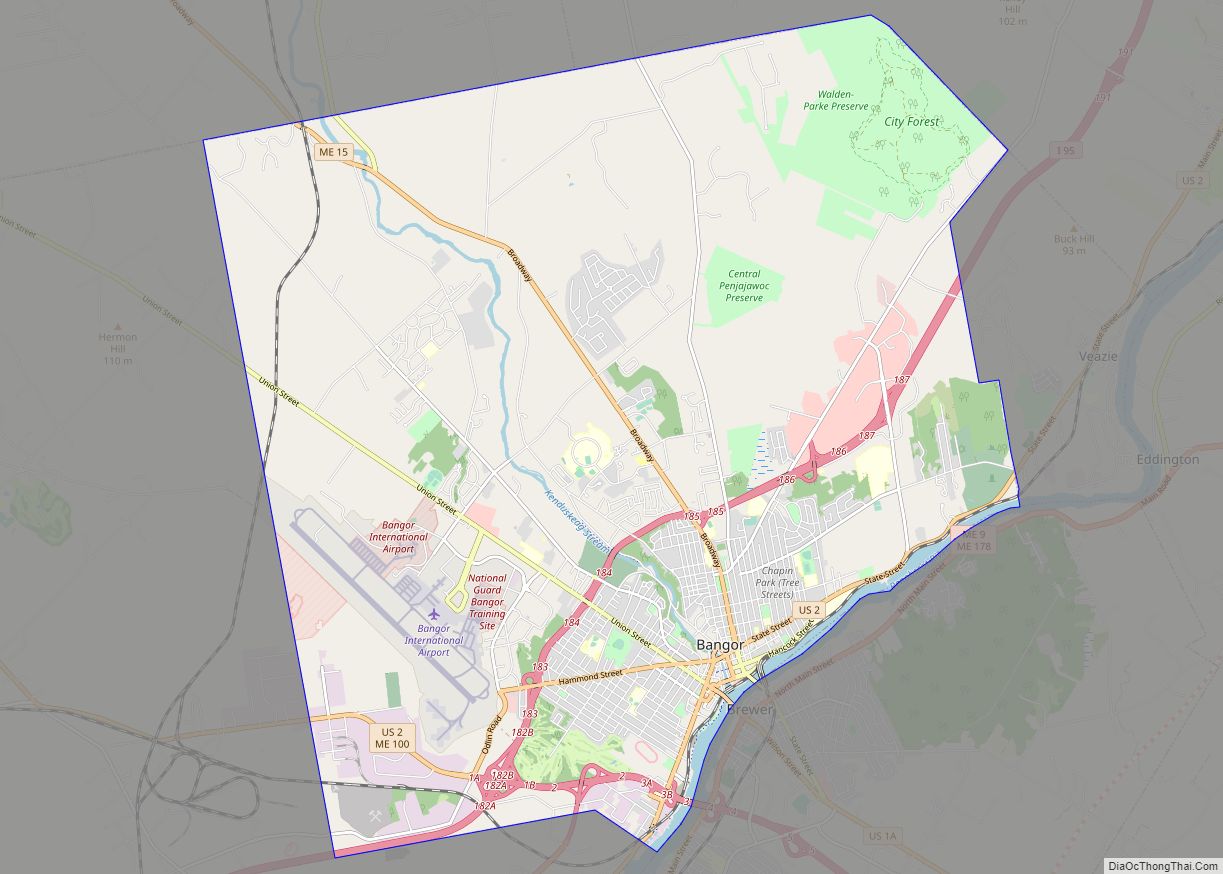

Bangor city Satellite Map

Geography

Bangor is located at 44°48′N 68°48′W / 44.8°N 68.8°W / 44.8; -68.8. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 34.59 square miles (89.59 km), of which 34.26 square miles (88.73 km) is land and 0.33 square miles (0.85 km) is water.

A potential advantage that has always eluded exploitation is the city’s location between the port city of Halifax, Nova Scotia, and the rest of Canada (as well as New York). As early as the 1870s, the city promoted a Halifax-to-New York railroad, via Bangor, as the quickest connection between North America and Europe (when combined with steamship service between Britain and Halifax). A European and North American Railway opened through Bangor, with President Ulysses S. Grant officiating at the inauguration, but commerce never lived up to the potential. More recent attempts to capture traffic between Halifax and Montreal by constructing an East–West Highway through Maine have also come to naught. Most overland traffic between the two parts of Canada continues to travel north of Maine rather than across it.

Urban development

Major fires struck the downtown in 1856, 1869, and 1872, the last resulting in the erection of the Adams-Pickering Block. In the Great Fire of 1911 Bangor lost its high school, post office & custom house, public library, telephone and telegraph companies, banks, two fire stations, nearly a hundred businesses, six churches, and synagogue and 285 private residences over a total of 55 acres (23 ha.) The area was rebuilt, and in the process became a showplace for a diverse range of architectural styles, including the Mansard style, Beaux Arts, Greek Revival and Colonial Revival, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Great Fire of 1911 Historic District.

The destruction of downtown landmarks such as the old city hall and train station in the late 1960s urban renewal program is now considered to have been a mistake. It ushered in a decline of the city center that was accelerated by the construction of the Bangor Mall in 1978 and subsequent big-box stores on the city’s outskirts. Downtown Bangor began to recover in the 1990s, with bookstores, café/restaurants, galleries, and museums filling once-vacant storefronts. The recent re-development of the city’s waterfront has also helped re-focus cultural life in the historic center.

Hydrology

Bangor is on the banks of the Penobscot River, close enough to the Atlantic Ocean to be influenced by tides. Upstream, the Penobscot River drainage basin occupies 8,570 square miles (22,200 km) in northeastern Maine. Flooding is most often caused by a combination of precipitation and snowmelt. Ice jams can exacerbate high flow conditions and cause acute localized flooding. Conditions favorable for flooding typically occur during the spring months.

In 1807 an ice jam formed below Bangor Village raising the water 10 to 12 feet (3 to 3.7 m) above the normal highwater mark and in 1887 the freshet caused the Maine Central Railroad Company rails between Bangor and Vanceboro to be covered to a depth of several feet. Bangor’s worst ice jam floods occurred in 1846 and 1902. Both resulted from mid-December freshets that cleared the upper river of ice, followed by cold that produced large volumes of frazil ice or slush which was carried by high flows forming a major ice jam in the lower river. In March of both years, a dynamic breakup of ice ran into the jam and flooded downtown Bangor. Though no people died and the city recovered quickly, the 1846 and 1902 ice jam floods were economically devastating, according to the Army Corps analysis. Both floods occurred with multiple dams in place and little to no ice-breaking in the lower river. The United States Coast Guard began icebreaker operations on the Penobscot in the 1940s, preventing the formation of frozen ice jams during the winter and providing an unobstructed path for ice-out in the spring. Long-term temperature records show a gradual warming since 1894, which may have reduced the ice jam flood potential at Bangor.

In the Groundhog Day gale of 1976 a storm surge went up the Penobscot, flooding Bangor for three hours. At 11:15 am, waters began rising on the river and within 15 minutes had risen a total of 3.7 metres (12 ft) flooding downtown. About 200 cars were submerged and office workers were stranded until waters receded. There were no reported deaths during this unusual flash flood.

Climate

Bangor has a humid continental climate (Köppen: Dfb), with cold, snowy winters, and warm summers, and is in USDA hardiness zone 5a. The monthly daily average temperature ranges from 18.5 °F (−7.5 °C) in January to 69.5 °F (20.8 °C) in July. On average, there are 20 nights annually that drop to 0 °F (−18 °C) or below, and 55 days where the temperature stays below freezing, including 49 days from December through February. There is an average of 6.1 days annually with highs at or above 90 °F (32 °C), with the last year to have not seen such temperatures being 2014. Extreme temperatures range from −32 °F (−36 °C) on February 10, 1948, up to 104 °F (40 °C) on August 19, 1935.

The average first freeze of the season occurs on October 7, and the last May 7, resulting in a freeze-free season of 152 days; the corresponding dates for measurable snowfall, i.e. at least 0.1 in (0.25 cm), are November 23 and April 4. The average annual snowfall for Bangor is approximately 74.6 inches (189 cm), while snowfall has ranged from 22.2 inches (56 cm) in 1979–80 to 181.9 inches (4.62 m) in 1962−63; the record snowiest month was February 1969 with 58.0 inches (147 cm), while the most snow in one calendar day was 30.0 inches (76 cm) on December 14, 1927. A snow depth of at least 3 in (7.6 cm) is on average seen 66 days per winter, including 54 days from January to March, when the snow pack is typically most reliable.

See also

Map of Maine State and its subdivision: Map of other states:- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming