Dover is a city in Strafford County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 32,741 at the 2020 census, making it the largest city in the New Hampshire Seacoast region and the fifth largest municipality in the state. It is the county seat of Strafford County, and home to Wentworth-Douglass Hospital, the Woodman Institute Museum, and the Children’s Museum of New Hampshire.

| Name: | Dover city |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 25 |

| LSAD Description: | city (suffix) |

| State: | New Hampshire |

| County: | Strafford County |

| Incorporated: | 1623 (town) |

| Elevation: | 50 ft (15 m) |

| Total Area: | 29.04 sq mi (75.22 km²) |

| Land Area: | 26.73 sq mi (69.23 km²) |

| Water Area: | 2.31 sq mi (6.00 km²) 7.97% |

| Population Density: | 1,224.92/sq mi (472.95/km²) |

| Area code: | 603 |

| FIPS code: | 3318820 |

| GNISfeature ID: | 0866618 |

| Website: | www.dover.nh.gov |

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

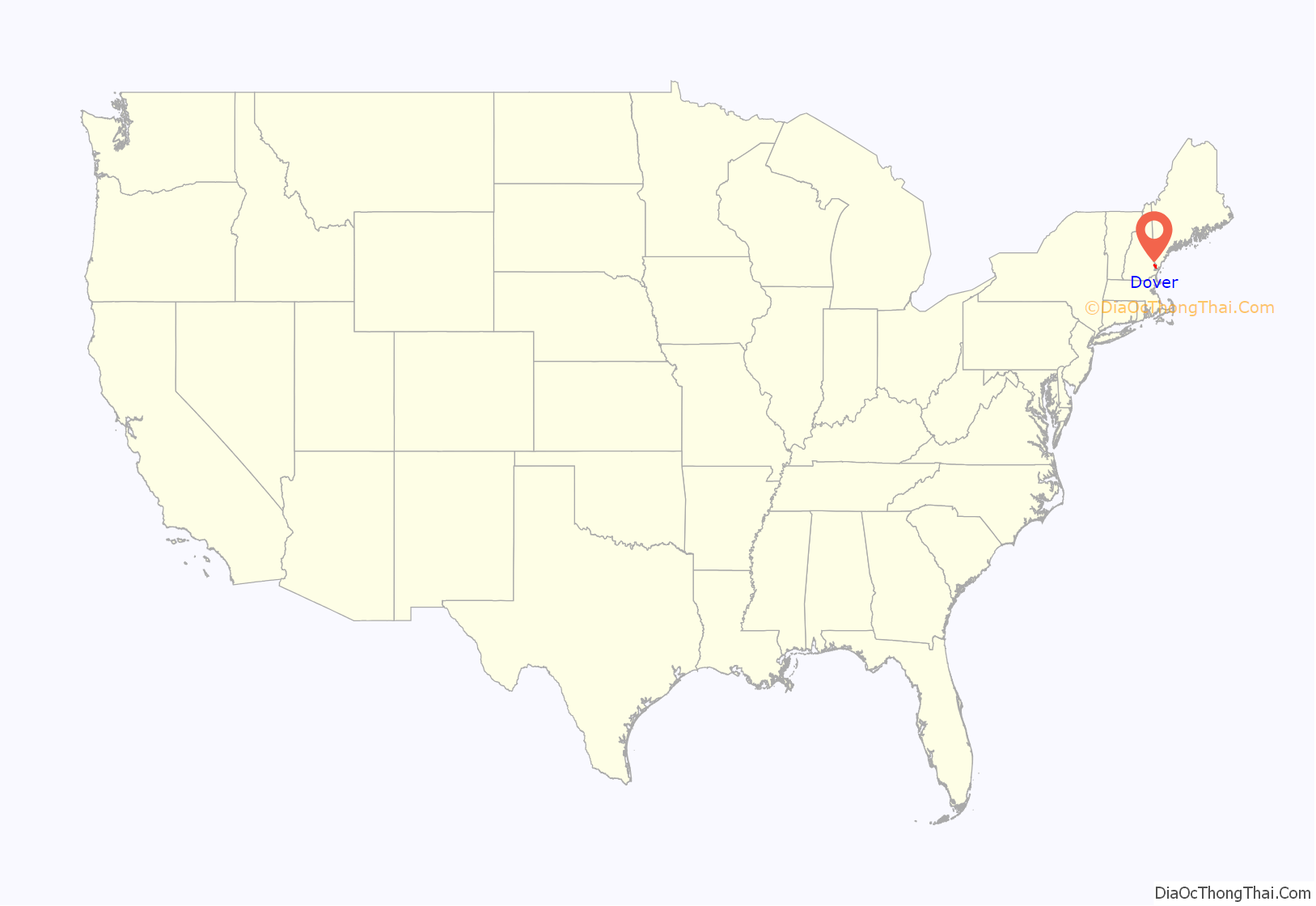

Dover location map. Where is Dover city?

History

Settlement

The first known European to explore the region was Martin Pring from Bristol, England, in 1603. In 1623, William and Edward Hilton settled at Pomeroy Cove on Dover Point, making Dover the oldest permanent settlement in New Hampshire, and seventh in the United States. One of the colony’s four original townships, it then included Durham, Madbury, Newington, Lee, Somersworth and Rollinsford.

The Hiltons’ name survives at Hilton Park on Dover Point (originally known as Hilton Point), where the brothers settled near the confluence of the Bellamy and Piscataqua rivers. They were fishmongers sent from London by the Company of Laconia to establish a colony and fishery on the Piscataqua. In 1631, however, it contained only three houses. William Hilton built a salt works on the property (salt-making was the principal industry in his hometown of Northwich, England). He also served as Deputy to the General Court (the colonial legislature).

In 1633, the plantation was bought by a group of English Puritans who planned to settle in New England, including Viscount Saye and Sele, Baron Brooke and John Pym. They promoted colonization in America, and that year Hilton’s Point received numerous immigrants, many from Bristol. They renamed the settlement Bristol. Atop the nearby hill they built a meetinghouse surrounded by an entrenchment, with a jail nearby.

The town was called Dover in 1637 by the new governor, Reverend George Burdett. It was possibly named after Robert Dover, an English lawyer who resisted Puritanism. With the 1639 arrival of Thomas Larkham, however, it was renamed after Northam in Devon, where he had been preacher. But Lord Saye and Sele’s group lost interest in their settlements, both here and at Saybrook, Connecticut, when their plan to establish a hereditary aristocracy in the colonies met disfavor in New England. Consequently, the plantation was sold in 1641 to Massachusetts and again named Dover.

Settlers built fortified log houses called garrisons, inspiring Dover’s nickname “The Garrison City.” The population and business center shifted from Dover Point to Cochecho Falls on the Cochecho River, where its drop of 34 feet (10 m) providing water power for industry (Cochecho means “the rapid foaming water” in the Abenaki language). What is now downtown Dover settlers called Cochecho village.

Cochecho Massacre

On June 28, 1689, Dover suffered a devastating attack by Native Americans. It was revenge for an incident on September 7, 1676, when 400 Native Americans were tricked by Major Richard Waldron into performing a “mock battle” near Cochecho Falls. After discharging their weapons, the Native American warriors were captured. Half were sent to Massachusetts for predations committed during King Philip’s War, then either hanged or sold into slavery. Local Native Americans deemed innocent were released, but considered the deception a dishonorable breach of hospitality. Thirteen years passed. When colonists thought the episode forgotten, they struck. Fifty-two colonists, a quarter of the population, were either captured or slain.

Incursions against the frontier town would continue for the next half century. During Father Rale’s War, in August and September 1723, there were Indian raids on Saco, Maine, and Dover, New Hampshire. The following year Dover was raided again and Elizabeth Hanson wrote her captivity narrative.

Mill era

Located at the head of navigation, Cochecho Falls brought the Industrial Revolution to 19th-century Dover in a big way. But cotton textile manufacturing actually began about two miles upstream with the Dover Cotton Factory, which was incorporated in 1812, its mill built in 1815. The business would move to Cochecho Falls when it acquired water privileges occupied since the 17th-century by sawmills and gristmills. In 1823 it was renamed the Dover Manufacturing Company, but was not successful. So in 1827 the Cocheco Manufacturing Company was founded (the misspelling a clerical error at incorporation). Expansive brick mills were constructed downtown, linked to receive cotton bales and ship finished cloth when the railroad arrived in 1842. Incorporated as a city in 1855, Dover for a time became a leading national producer of textiles, the mill complex dominating the riverfront and employing 2000 workers.

The mills were purchased in 1909 by the Pacific Mills of Lawrence, Massachusetts, which closed the printery in 1913 but continued spinning and weaving. The printery buildings were demolished in 1913, their site is now Henry Law Park. During the Great Depression, however, textile mills no longer dependent on New England water power began moving to southern states in search of cheaper operating conditions, or simply went out of business. Dover’s millyard shut in 1937, then was bought at auction in 1941 by the city itself for $54,000. There were no other bids. Now called the Cocheco Falls Millworks, its tenants include technology and government services companies, plus a restaurant, brewery and bar.

Textile manufacturing in Dover wasn’t limited to cotton. In 1824, Alfred I. Sawyer established the Sawyer Woolen Mills beside the Bellamy River. It would expand to include 15 major buildings over 8.5-acres, and by 1883 was the largest woolen manufacturer in the state. In 1889 it was acquired by the American Woolen Company, but closed and was sold off in 1955. The buildings have been repurposed into housing.

Modern era

With the closing of the mills, the downtown area of Dover sat vacant and lifeless for a long time. With the turn of the century, the city government began to revitalize the area. The Children’s Museum of New Hampshire was brought into a disused mill building with a lease of $1 a year. Henry Law Park, a grassy waterfront stretch of land, was given a brand new playground. Small businesses moved into the mills, such as restaurants, toy stores, real estate offices, and barber shops. Old buildings have been refurbished or outright rebuilt to provide new housing. An $87.5 million high school was built to handle the influx of new residents retreating from the high housing prices in Portsmouth. Recently, a plan to develop the waterfront on the other side of the river from the traditional downtown area was approved for $6 million. In early May 2021, waypoint signs were sporadically added to help drivers and walkers navigate Dover with the expansions that are underway.

Antique postcards

The Old Corner c. 1892

Central Square c. 1905

Public Library c. 1907

Guppy House c. 1910

Old Brick Schoolhouse c. 1910, once located near Pine Hill Cemetery

Cochecho Falls c. 1910

Whitcher’s Falls c. 1910

Pacific Mills c. 1912

Downtown c. 1913

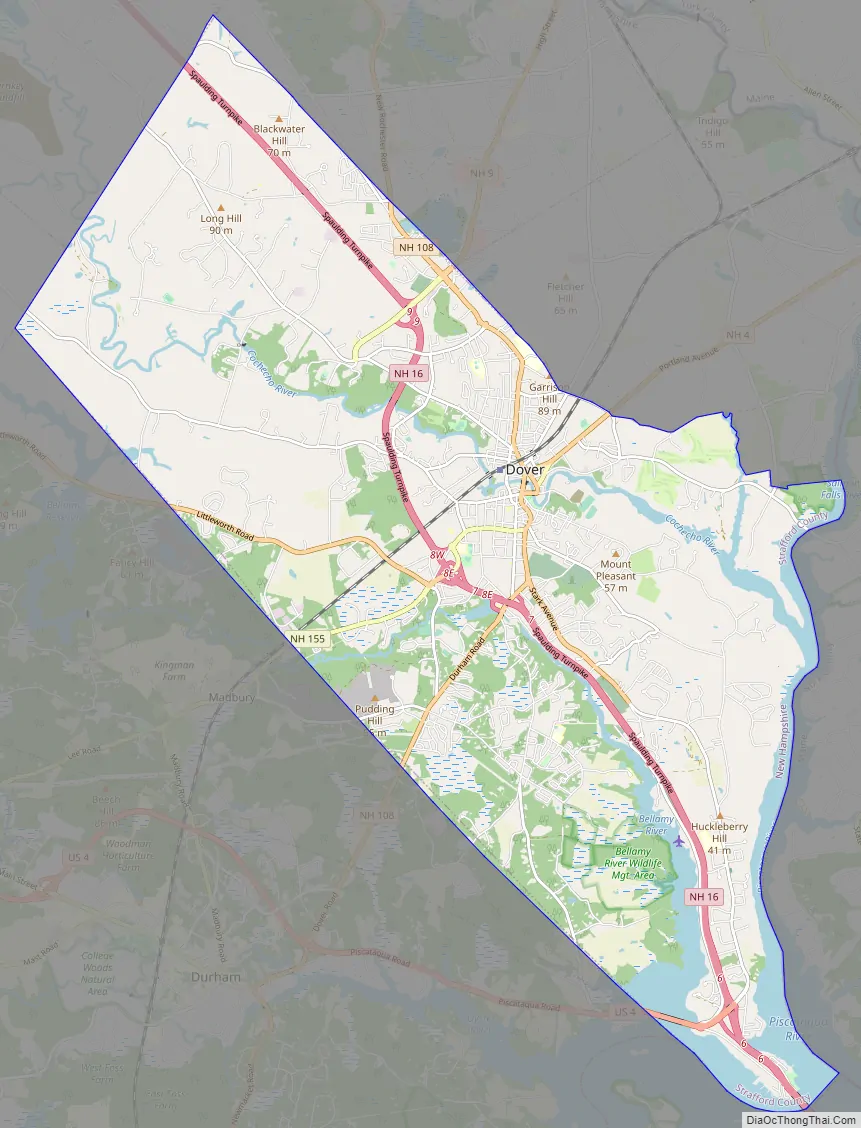

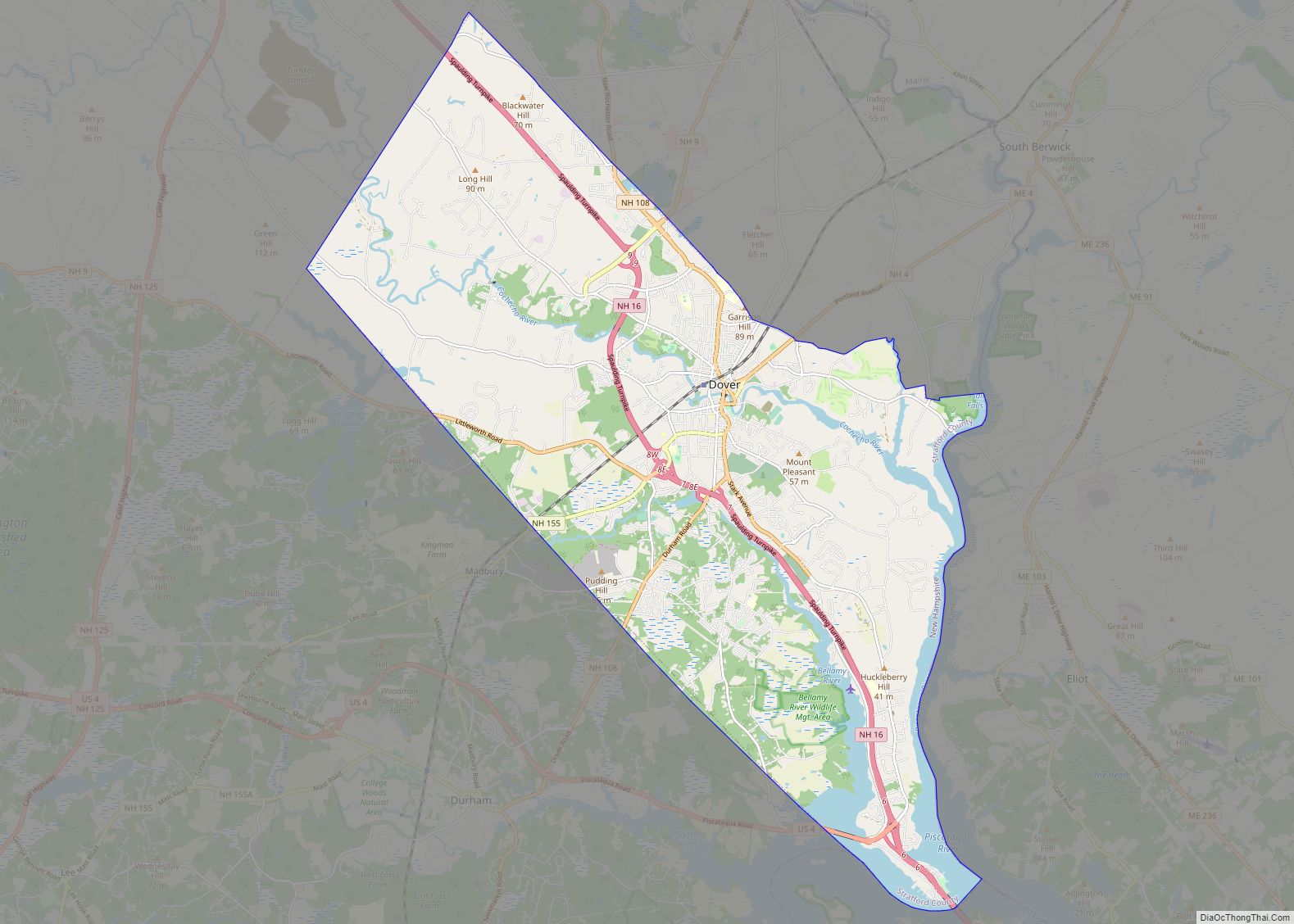

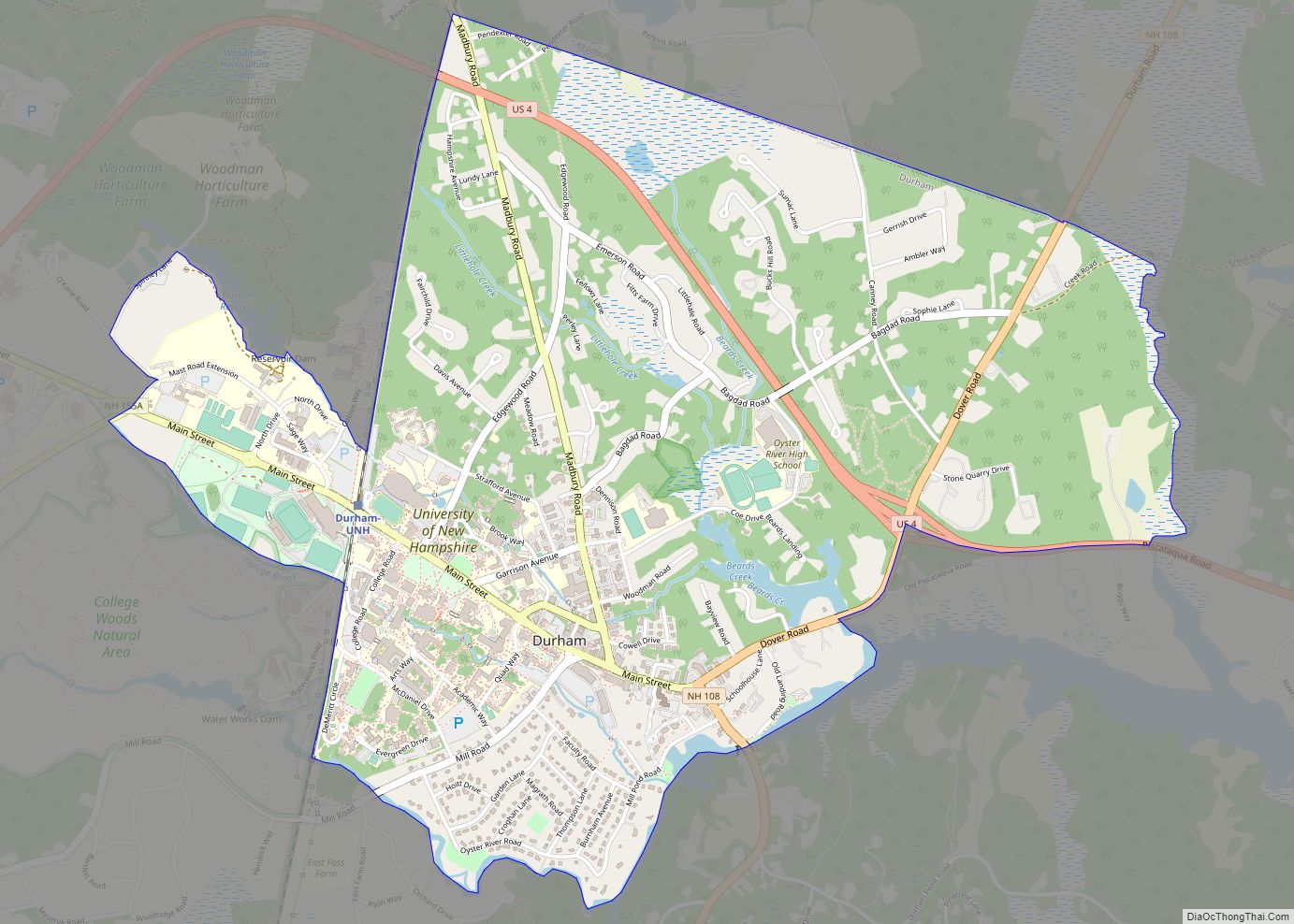

Dover Road Map

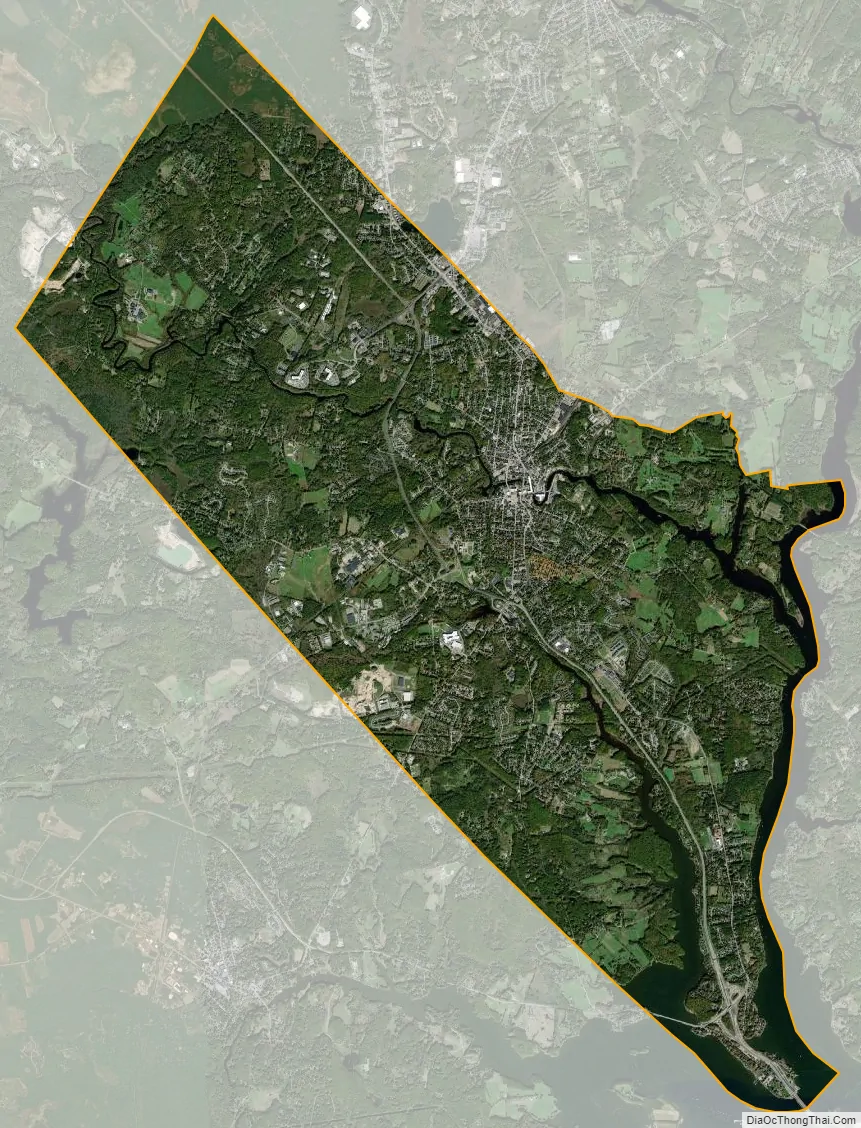

Dover city Satellite Map

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 29.0 square miles (75.2 km), of which 26.7 square miles (69.2 km) are land and 2.3 square miles (6.0 km) are water, comprising 7.97% of the city. Dover is drained by the Cochecho and Bellamy rivers, both of which flow into the tidal Piscataqua River, which forms the city’s eastern boundary and the New Hampshire–Maine border. Long Hill, elevation greater than 300 feet (91 m) above sea level and located 3 miles (5 km) northwest of the city center, is the highest point in Dover. Garrison Hill, elevation approximately 290 ft (88 m), is a prominent hill rising directly above the center city, with a park and lookout tower on top.

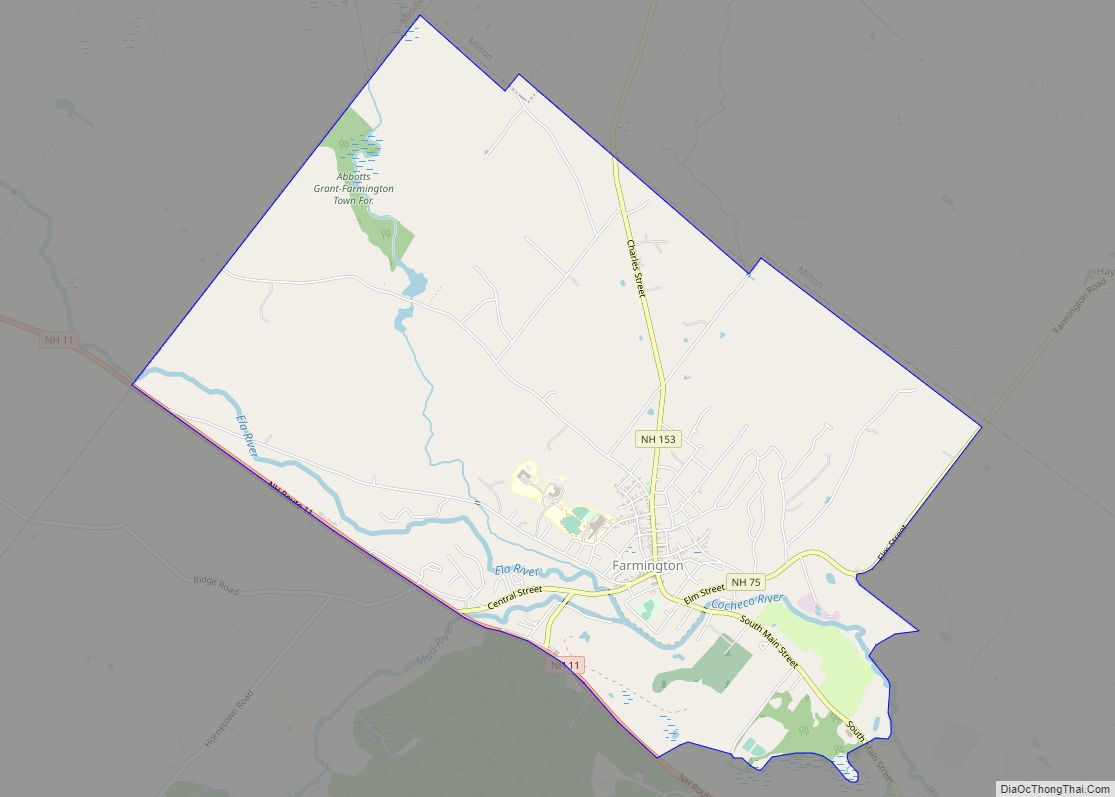

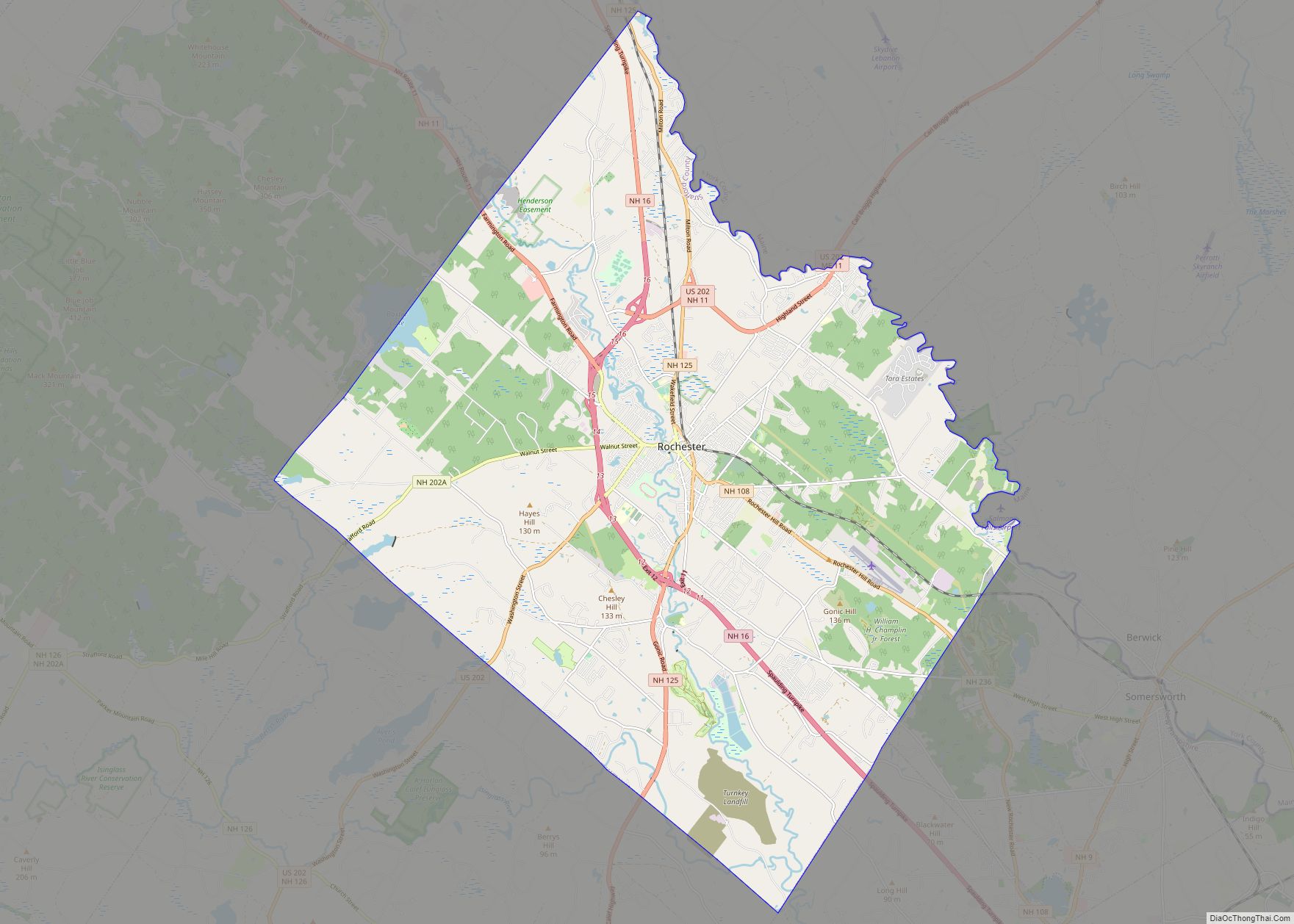

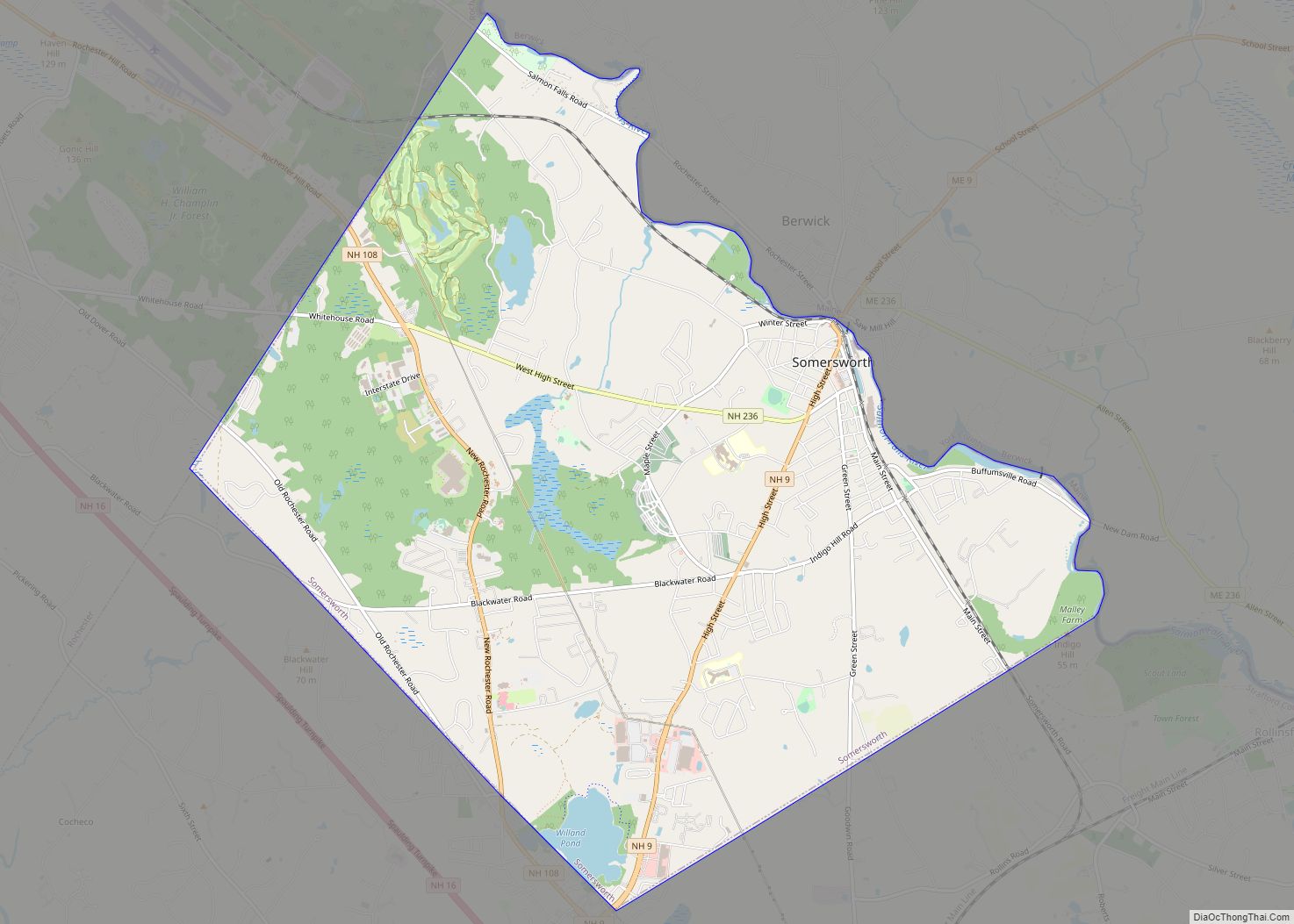

The city is crossed by New Hampshire Routes 4, 9, 16 (the Spaulding Turnpike), 108, and 155, plus U.S. Route 4. It is bordered by the town of Newington to the south (across the inlet to Great Bay), Madbury to the southwest, Barrington and Rochester to the northwest, and Somersworth and Rollinsford to the northeast. South Berwick, Maine, lies to the northeast, across the tidal Salmon Falls River, and Eliot, Maine, is to the east, across the Piscataqua River.

The Cooperative Alliance for Seacoast Transportation (COAST) operates a publicly funded bus network in Dover and surrounding communities in New Hampshire and Maine. C&J Trailways is a private intercity bus carrier connecting Dover with other coastal New Hampshire and Massachusetts cities, including Boston, as well as direct service to New York City. Wildcat Transit, operated by the University of New Hampshire, provides bus service to Durham, which is free for students and $1.50 for the public. Amtrak’s Downeaster train service stops at the Dover Transportation Center with service to the Portland Transportation Center, Boston’s North Station, and intermediate stops.

See also

Map of New Hampshire State and its subdivision: Map of other states:- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming