Santa Fe (/ˌsæntə ˈfeɪ, ˈsæntə feɪ/ SAN-tə FAY, - fay; Spanish: [santaˈfe], Spanish for ‘Holy Faith’; Tewa: Oghá P’o’oge, Tewa for ‘white shell water place’; Northern Tiwa: Hulp’ó’ona; Navajo: Yootó, Navajo for ‘bead + water place’) is the capital of the U.S. state of New Mexico. The name “Santa Fe” means ‘Holy Faith’ in Spanish, and the city’s full name as founded remains La Villa Real de la Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asís (‘The Royal Town of the Holy Faith of Saint Francis of Assisi’).

With a population of 87,505 at the 2020 census, it is the fourth-largest city in New Mexico. It is also the county seat of Santa Fe County. Its metropolitan area is part of the Albuquerque–Santa Fe–Las Vegas combined statistical area, which had a population of 1,162,523 in 2020. Human settlement dates back thousands of years in the region. The placita was founded in 1610 as the capital of Nuevo México. It replaced the previous capital, San Juan de los Caballeros, near modern Española, at San Gabriel de Yungue-Ouinge, which makes it the oldest state capital in the United States. It is also at the highest altitude of any of the U.S. state capitals, with an elevation of 7,199 feet (2,194 m).

Santa Fe is widely considered one of the country’s great art cities, due to its many art galleries and installations, and it is recognized by UNESCO’s Creative Cities Network. Its cultural highlights include Santa Fe Plaza, the Palace of the Governors, the Fiesta de Santa Fe, numerous restaurants featuring distinctive New Mexican cuisine, and performances of New Mexico music. Among its many art galleries and installations are the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, a gallery by cartoonist Chuck Jones, and newer art collectives such as Meow Wolf. The cityscape is known for its adobe-style Pueblo Revival and Territorial Revival architecture.

| Name: | Santa Fe city |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 25 |

| LSAD Description: | city (suffix) |

| State: | New Mexico |

| County: | Santa Fe County |

| Founded: | 1610; 413 years ago (1610) |

| Elevation: | 6,998 ft (2,133 m) |

| Land Area: | 52.23 sq mi (135.28 km²) |

| Water Area: | 0.11 sq mi (0.29 km²) |

| Population Density: | 1,675.28/sq mi (646.83/km²) |

| Area code: | 505 |

| FIPS code: | 3570500 |

| GNISfeature ID: | 936823 |

| Website: | santafenm.gov |

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

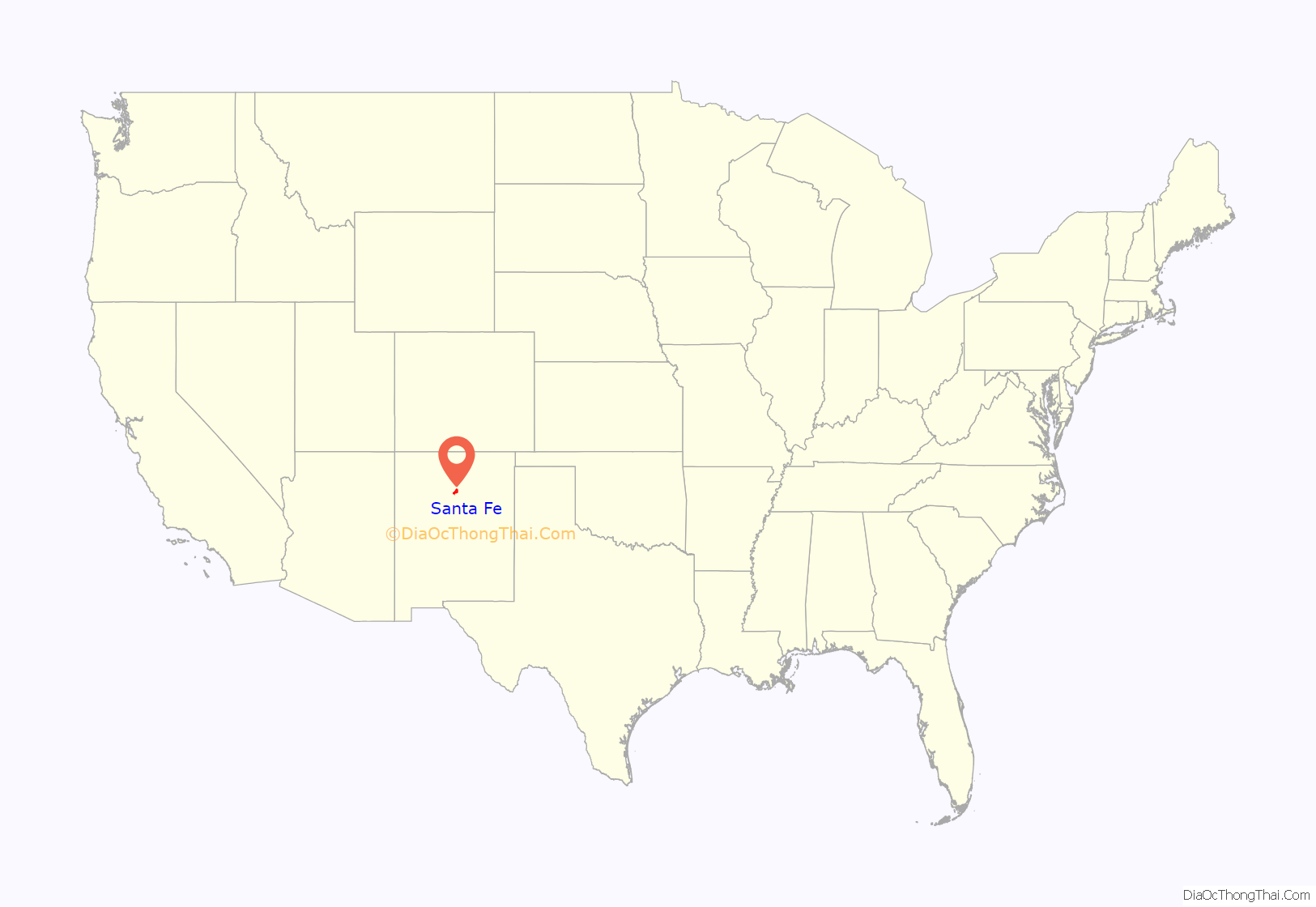

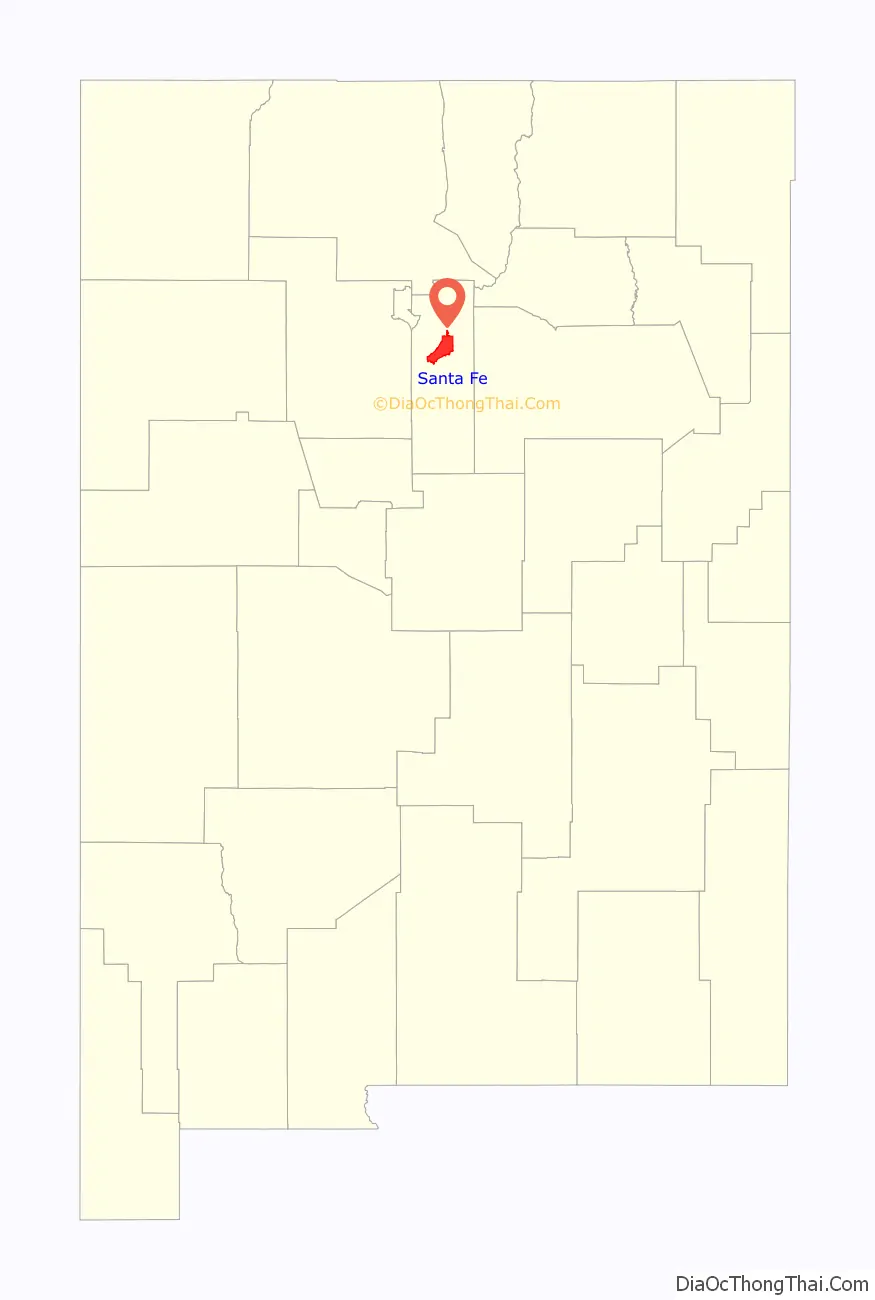

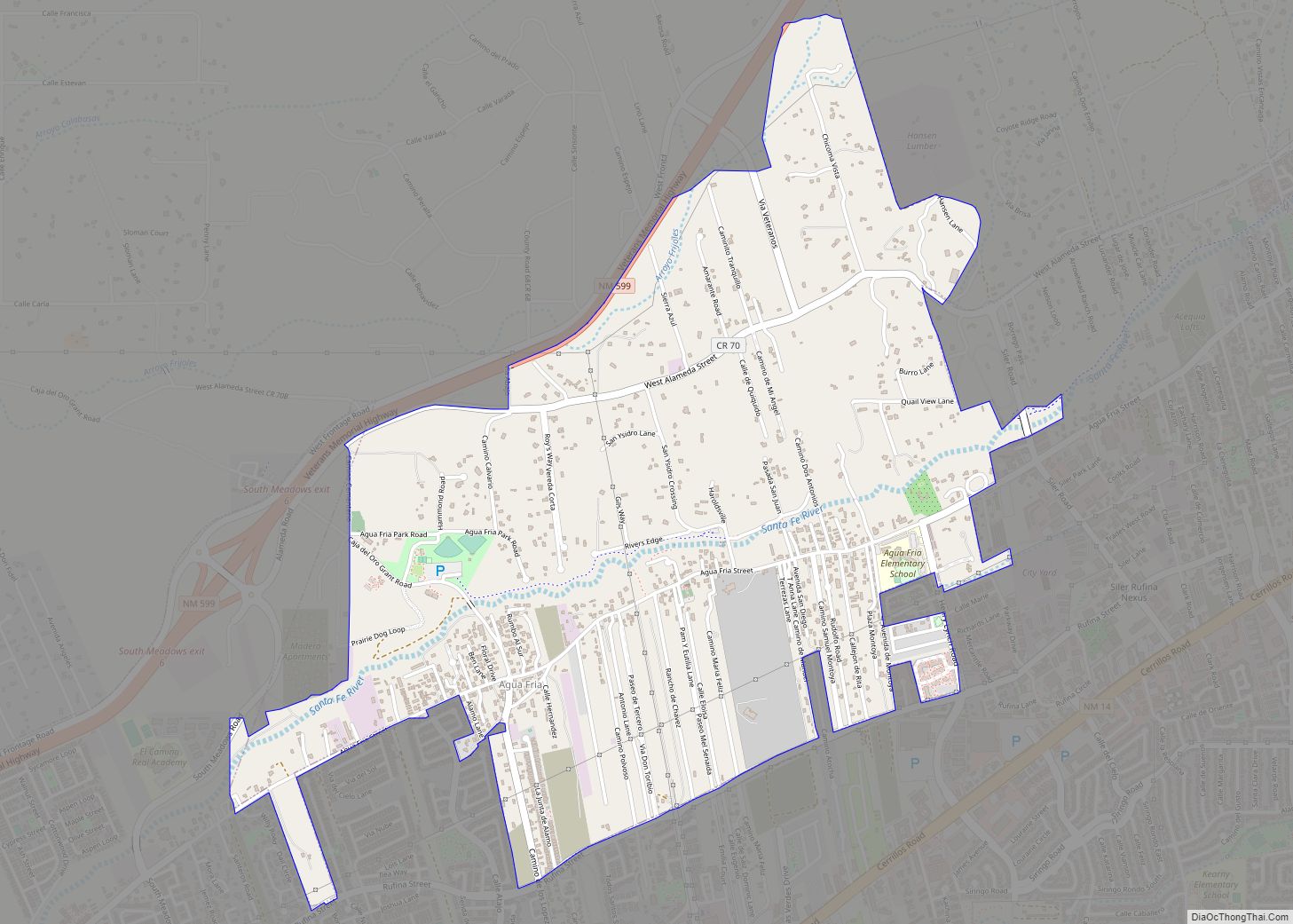

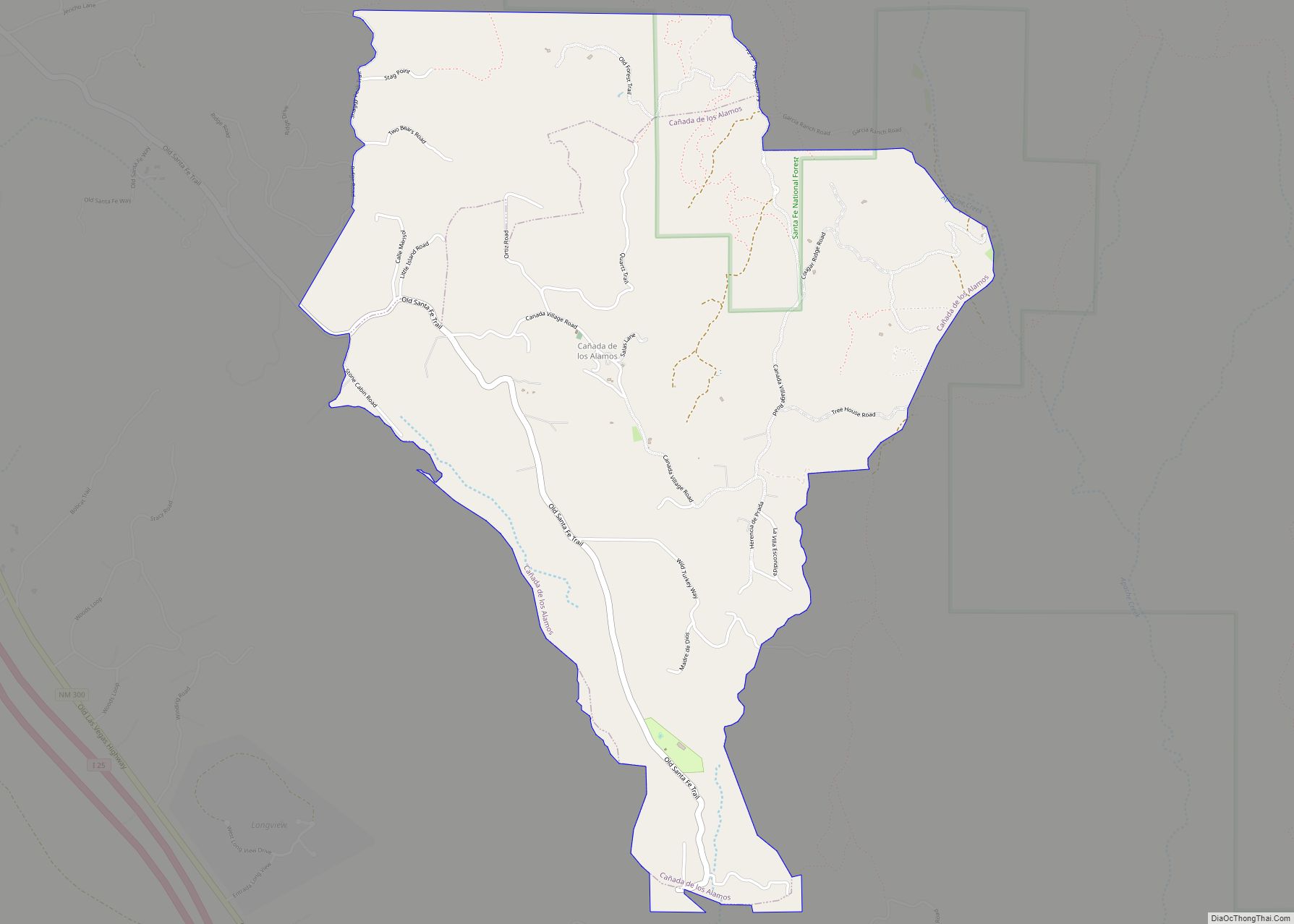

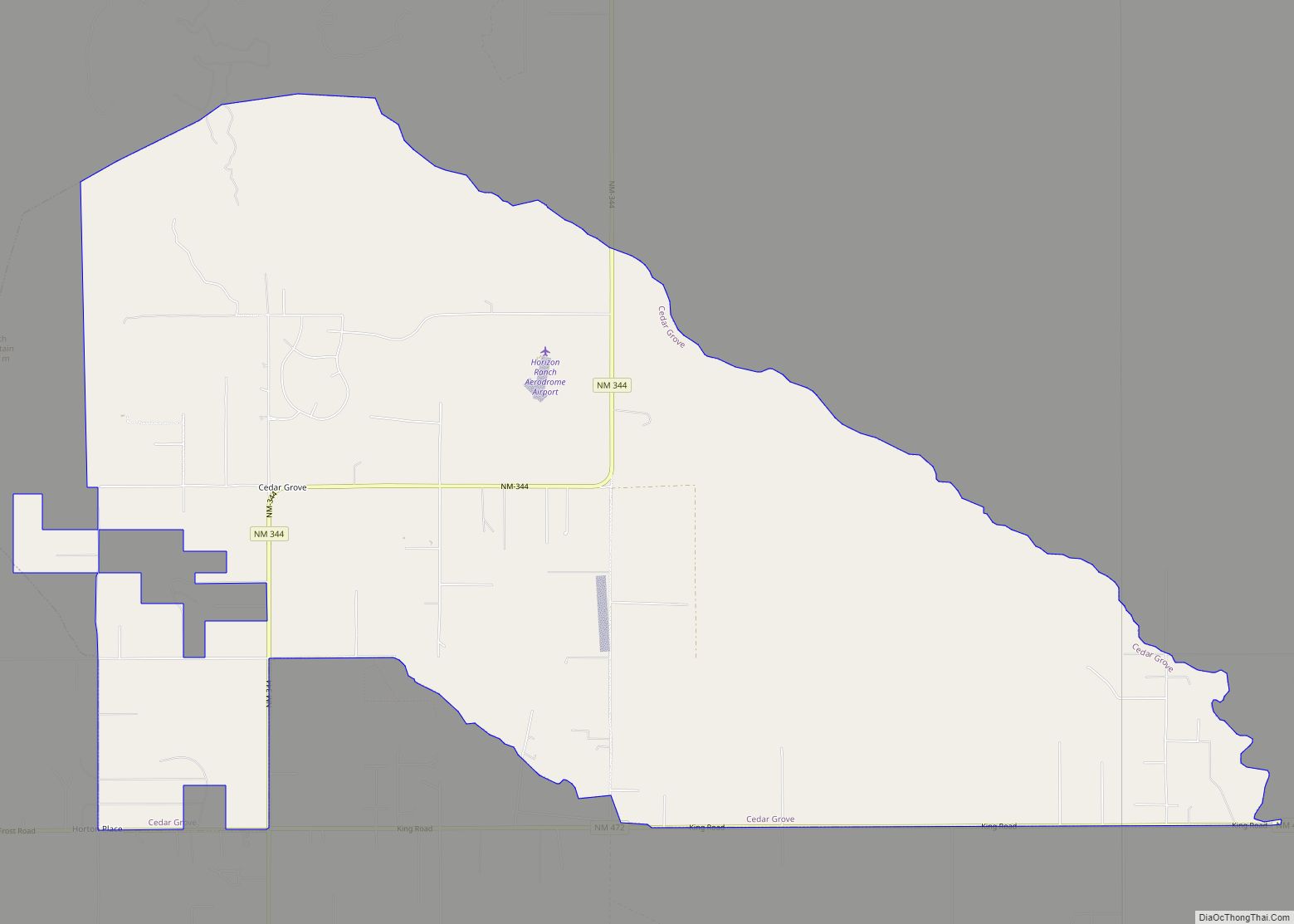

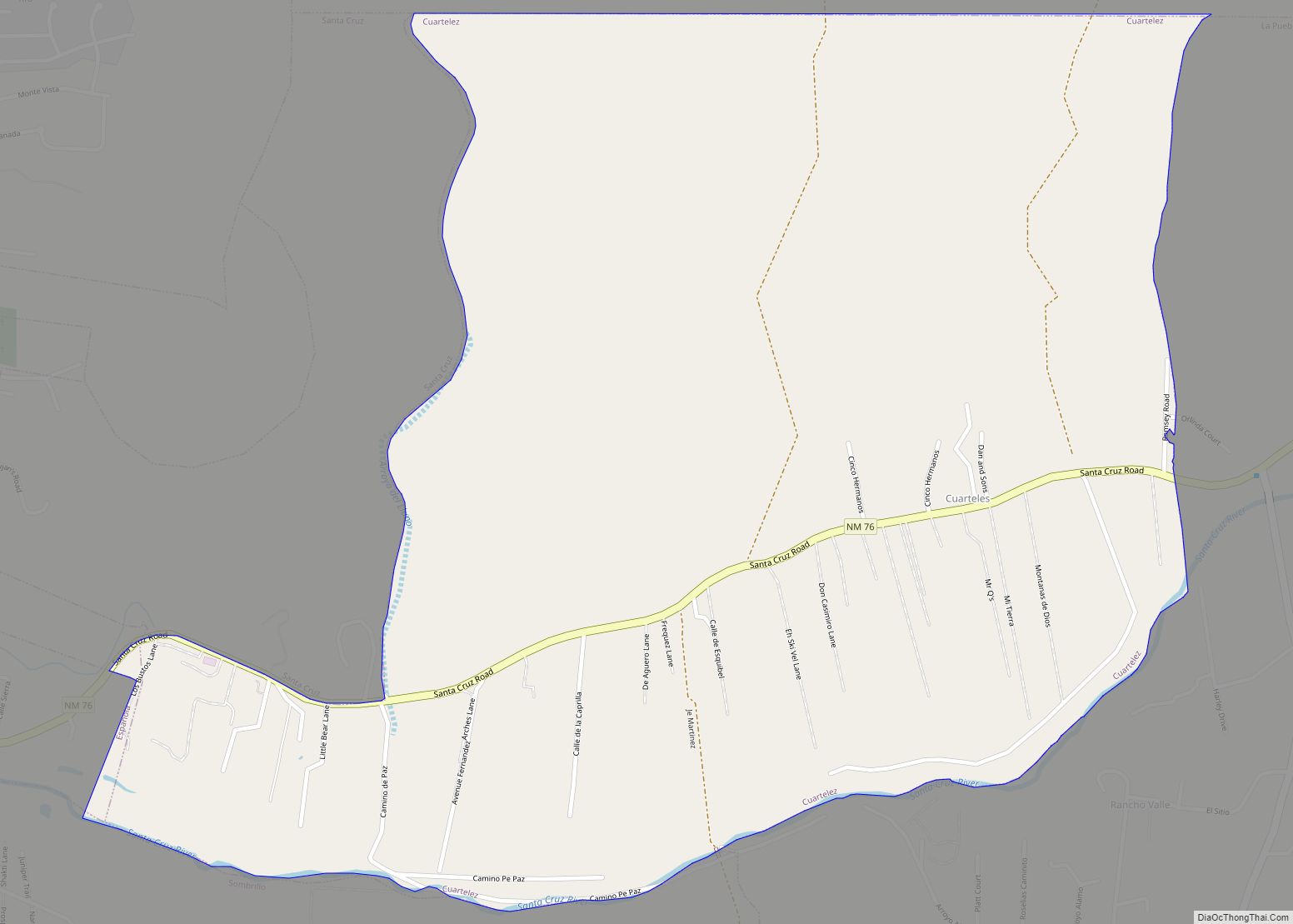

Santa Fe location map. Where is Santa Fe city?

History

Spain and Mexico

The area of Santa Fe was originally occupied by indigenous Tanoan peoples, who lived in numerous Pueblo villages along the Rio Grande. One of the earliest known settlements in what is known as downtown Santa Fe today came sometime after 900 AD. A group of native Tewa built a cluster of homes that centered around the site of today’s Plaza and spread for half a mile to the south and west; the village was called Oghá P’o’oge in Tewa. The Tanoans and other Pueblo peoples settled along the Santa Fe River for its water and transportation.

The river had a year-round flow until the 1700s. By the 20th century the Santa Fe River was a seasonal waterway. As of 2007, the river was recognized as the most endangered river in the United States, according to the conservation group American Rivers.

Don Juan de Oñate led the first Spanish effort to colonize the region in 1598, establishing Santa Fe de Nuevo México as a province of New Spain. Under Juan de Oñate and his son, the capital of the province was the settlement of San Juan de los Caballeros north of Santa Fe near modern Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo. Juan de Oñate was banished and exiled from New Mexico by the Spanish, after his rule was deemed cruel towards the indigenous population. New Mexico’s second Spanish governor, Don Pedro de Peralta, however, founded a new city at the foot of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in 1607, which he called La Villa Real de la Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asís, the Royal Town of the Holy Faith of Saint Francis of Assisi. In 1610, he designated it as the capital of the province, which it has almost constantly remained, making it the oldest state capital in the United States.

Lack of Native American representation within the province of Santa Fe de Nuevo México, New Spain (current New Mexico’s early government) led to the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, when groups of different Native Pueblo peoples were successful in driving the Spaniards out of New Mexico to El Paso. The Pueblo people continued running New Mexico from the Palace of the Governors in Santa Fe from 1680 to 1692. The territory was reconquered in 1692 by Don Diego de Vargas through the so-called “Bloodless Reconquest”, which was criticized as violent even at the time. The next governor, Francisco Cuervo y Valdez, started to broker peace, including the founding of Albuquerque, to guarantee better representation and trade access for Pueblos in New Mexico’s government. Other governors of New Mexico, such as Tomás Vélez Cachupin, continued to be better known for their more forward thinking work with the indigenous population of New Mexico. Santa Fe was Spain’s provincial seat at outbreak of the Mexican War of Independence in 1810. It was considered important to fur traders based in present-day Saint Louis, Missouri. When the area was still under Spanish rule, the Chouteau brothers of Saint Louis gained a monopoly on the fur trade, before the United States acquired Missouri under the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. The fur trade contributed to the wealth of Saint Louis. The city’s status as the capital of the Mexican territory of Santa Fe de Nuevo México was formalized in the 1824 Constitution after Mexico achieved independence from Spain.

When the Republic of Texas seceded from Mexico in 1836, it attempted to claim Santa Fe and other parts of Nuevo México as part of the western portion of Texas along the Río Grande. In 1841, a small military and trading expedition set out from Austin, intending to take control of the Santa Fe Trail. Known as the Texan Santa Fe Expedition, the force was poorly prepared and was easily captured by the New Mexican military.

Santa Fe, the country’s oldest capital, witnessed multiple migrations through the three trails that led to the city, as well as the advent of rails, Route 66, and the interstate.

United States

In 1846, the United States declared war on Mexico. Brigadier General Stephen W. Kearny led the main body of his Army of the West of some 1,700 soldiers into Santa Fe to claim it and the whole New Mexico Territory for the United States. By 1848 the U.S. officially gained New Mexico through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

Colonel Alexander William Doniphan, under the command of Kearny, recovered ammunition from Santa Fe labeled “Spain 1776” showing both the lack of communications and quality of military support New Mexico received under Mexican rule.

After its annexation, Texas claimed Santa Fe along with other territory in eastern New Mexico. Texas Governor Peter H. Bell sent a letter to President Zachary Taylor, who died before he could read it, demanding that the U.S. Army stop defending New Mexico. In response, Taylor’s successor Millard Fillmore stationed additional troops to the area to halt any incursion by the Texas Militia. The territorial dispute was finally resolved by the Compromise of 1850, which designated the 103rd meridian west as Texas’s western border.

Some American visitors at first saw little promise in the remote town. One traveller in 1849 wrote:

In 1851, Jean Baptiste Lamy arrived, becoming bishop of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and Colorado in 1853. During his leadership, he traveled to France, Rome, Tucson, Los Angeles, St. Louis, New Orleans, and Mexico City. He built the Santa Fe Saint Francis Cathedral and shaped Catholicism in the region until his death in 1888.

As part of the New Mexico Campaign of the Civil War, General Henry Sibley occupied the city, flying the Confederate flag over Santa Fe for a few days in March 1862. Sibley was forced to withdraw after Union troops destroyed his logistical trains following the Battle of Glorieta Pass. The Santa Fe National Cemetery was created by the federal government after the war in 1870 to inter the Union soldiers who died fighting there.

On October 21, 1887, Anton Docher, “The Padre of Isleta”, went to New Mexico where he was ordained as a priest in the St Francis Cathedral of Santa Fe by Bishop Jean-Baptiste Salpointe. After a few years serving in Santa Fe, Bernalillo and Taos, he moved to Isleta on December 28, 1891. He wrote an ethnological article published in The Santa Fé Magazine in June 1913, in which he describes early 20th century life in the Pueblos.

As railroads were extended into the West, Santa Fe was originally envisioned as an important stop on the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. But as the tracks were constructed into New Mexico, the civil engineers decided that it was more practical to go through Lamy, a town in Santa Fe County to the south of Santa Fe. A branch line was completed from Lamy to Santa Fe in 1880. The Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad extended the narrow gauge Chili Line from the nearby city of Española to Santa Fe in 1886.

Neither was sufficient to offset the negative effects of Santa Fe’s having been bypassed by the main railroad route. It suffered gradual economic decline into the early 20th century. Activists created a number of resources for the arts and archaeology, notably the School of American Research, created in 1907 under the leadership of the prominent archaeologist Edgar Lee Hewett. In the early 20th century, Santa Fe became a base for numerous writers and artists. The first airplane to fly over Santa Fe was piloted by Rose Dugan, carrying Vera von Blumenthal as passenger. Together the two women started the development of the Pueblo Indian pottery industry, helping native women to market their wares. They contributed to the founding of the annual Santa Fe Indian Market.

In 1912, New Mexico was admitted as the United States of America‘s 47th state, with Santa Fe as its capital.

20th century

In 1912, when the town’s population was approximately 5,000 people, the city’s civic leaders designed and enacted a sophisticated city plan that incorporated elements of the contemporary City Beautiful movement, city planning, and historic preservation. The latter was particularly influenced by similar movements in Germany. The plan anticipated limited future growth, considered the scarcity of water, and recognized the future prospects of suburban development on the outskirts. The planners foresaw that its development must be in harmony with the city’s character.

After the mainline of the railroad bypassed Santa Fe, it lost population. However, artists and writers, as well as retirees, were attracted to the cultural richness of the area, the beauty of the landscapes, and its dry climate. Local leaders began promoting the city as a tourist attraction. The city sponsored architectural restoration projects and erected new buildings according to traditional techniques and styles, thus creating the Santa Fe Style.

Edgar L. Hewett, founder and first director of the School of American Research and the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe, was a leading promoter. He began the Santa Fe Fiesta in 1919 and the Southwest Indian Fair in 1922 (now known as the Indian Market). When Hewett tried to attract a summer program for Texas women, many artists rebelled, saying the city should not promote artificial tourism at the expense of its artistic culture. The writers and artists formed the Old Santa Fe Association and defeated the plan.

New Mexico voted against interning any of its citizens of Japanese heritage, so none of the Japanese New Mexicans were interned during World War II. During World War II, the federal government ordered a Japanese-American internment camp to be established. Beginning in June 1942, the Department of Justice arrested 826 Japanese-American men after the attack on Pearl Harbor; they held them near Santa Fe, in a former Civilian Conservation Corps site that had been acquired and expanded for the purpose. Although there was a lack of evidence and no due process, the men were held on suspicion of fifth column activity. Security at Santa Fe was similar to a military prison, with twelve-foot barbed wire fences, guard towers equipped with searchlights, and guards carrying rifles, side arms and tear gas. By September, the internees had been transferred to other facilities—523 to War Relocation Authority concentration camps in the interior of the West, and 302 to Army internment camps.

The Santa Fe site was used next to hold German and Italian nationals, who were considered enemy aliens after the outbreak of war. In February 1943, these civilian detainees were transferred to Department of Justice custody.

The camp was expanded at that time to take in 2,100 men segregated from the general population of Japanese-American inmates. These were mostly Nisei and Kibei who renounced their U.S. citizenship rather than sign an oath to “give up loyalty to the Japanese emperor” (offending them, since they had no identification with the emperor & were being asked to enlist in fighting him while their Japanese-born parents were interned) and other “troublemakers” from the Tule Lake Segregation Center. In 1945, four internees were seriously injured when violence broke out between the internees and guards in an event known as the Santa Fe Riot. The camp remained open past the end of the war; the last detainees were released in mid 1946. The facility was closed and sold as surplus soon after. The camp was located in what is now the Casa Solana neighborhood.

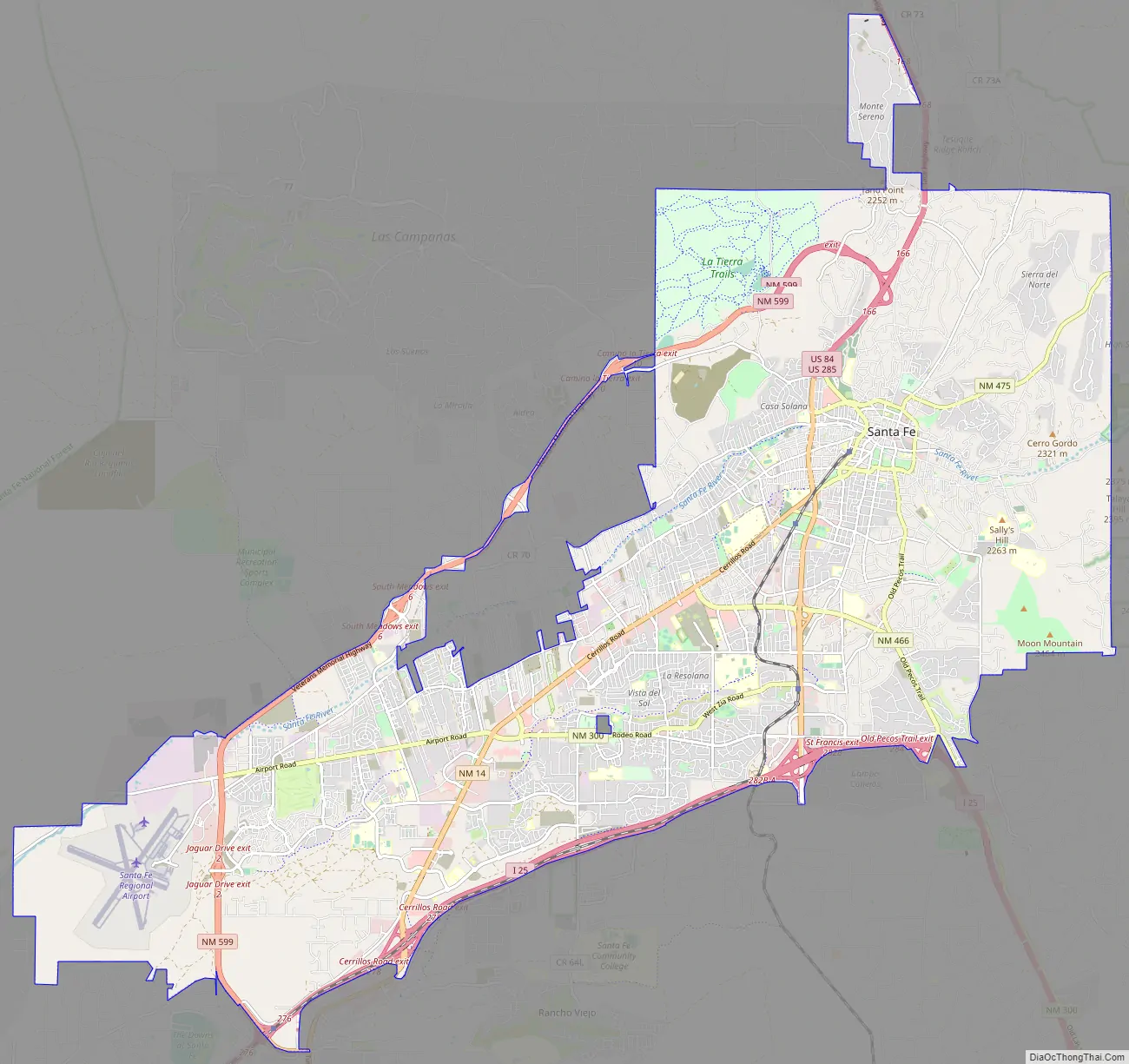

Santa Fe Road Map

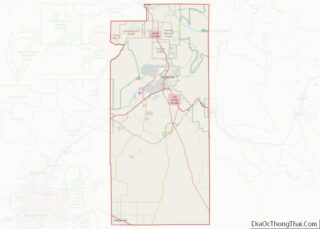

Santa Fe city Satellite Map

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 37.4 sq mi (96.9 km), of which 37.3 sq mi (96.7 km) are land and 0.077 sq mi (0.2 km) (0.21%) is covered by water.

Santa Fe is located at 7,199 feet (2,194 m) above sea level, making it the highest state capital in the United States.

The Santa Fe River and the arroyos of Santa Fe drain the region to the Rio Grande.

Climate

Santa Fe’s climate is characterized by cool, dry winters, hot summers, and relatively low precipitation. According to the Köppen climate classification, depending on which variant of the system is used, the city has either a subtropical highland climate (Cfb) or a warm-summer humid continental climate (Dfb), somewhat unusual at 35°N. The 24-hour average temperature in the city ranges from 30.3 °F (−0.9 °C) in December to 70.1 °F (21.2 °C) in July. Due to the relative aridity and elevation, average diurnal temperature variation exceeds 25 °F (14 °C) in every month, and 30 °F (17 °C) much of the year. The city usually receives six to eight snowfalls a year between November and April. The heaviest rainfall occurs in July and August, with the arrival of the North American Monsoon.

Spanish and Pueblo influences

The Spanish laid out the city according to the “Laws of the Indies”, town planning rules and ordinances which had been established in 1573 by King Philip II. The fundamental principle was that the town be laid out around a central plaza. On its north side was the Palace of the Governors, while on the east was the church that later became the Cathedral Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi.

An important style implemented in planning the city was the radiating grid of streets centered on the central Plaza. Many were narrow and included small alley-ways, but each gradually merged into the more casual byways of the agricultural perimeter areas. As the city grew throughout the 19th century, the building styles evolved too, so that by statehood in 1912, the eclectic nature of the buildings caused it to look like “Anywhere USA”. The city government realized that the economic decline, which had started more than twenty years before with the railway moving west and the federal government closing down Fort Marcy, might be reversed by the promotion of tourism.

To achieve that goal, the city created the idea of imposing a unified building style – the Spanish Pueblo Revival look, which was based on work done restoring the Palace of the Governors. The sources for this style came from the many defining features of local architecture: vigas (rough, exposed beams that extrude through supporting walls, and are thus visible outside as well as inside the building) and canales (rain spouts cut into short parapet walls around flat roofs), features borrowed from many old adobe homes and churches built many years before and found in the Pueblos, along with the earth-toned look (reproduced in stucco) of the old adobe exteriors.

After 1912 this style became official: all buildings were to be built using these elements. By 1930 there was a broadening to include the “Territorial”, a style of the pre-statehood period which included the addition of portales (large, covered porches) and white-painted window and door pediments (and also sometimes terra cotta tiles on sloped roofs, but with flat roofs still dominating). The city had become “different”. However, “in the rush to pueblofy” Santa Fe, the city lost a great deal of its architectural history and eclecticism. Among the architects most closely associated with this new style are T. Charles Gaastra and John Gaw Meem.

By an ordinance passed in 1957, new and rebuilt buildings, especially those in designated historic districts, must exhibit a Spanish Territorial or Pueblo style of architecture, with flat roofs and other features suggestive of the area’s traditional adobe construction. However, many contemporary houses in the city are built from lumber, concrete blocks, and other common building materials, but with stucco surfaces (sometimes referred to as “faux-dobe”, pronounced as one word: “foe-dough-bee”) reflecting the historic style.

In a September 2003 report by Angelou Economics, it was determined that Santa Fe should focus its economic development efforts in the following seven industries: Arts and Culture, Design, Hospitality, Conservation Technologies, Software Development, Publishing and New Media, and Outdoor Gear and Apparel. Three secondary targeted industries for Santa Fe to focus development in are health care, retiree services, and food & beverage. Angelou Economics recognized three economic signs that Santa Fe’s economy was at risk of long-term deterioration. These signs were; a lack of business diversity which tied the city too closely to fluctuations in tourism and the government sector; the beginnings of urban sprawl, as a result of Santa Fe County growing faster than the city, meaning people will move farther outside the city to find land and lower costs for housing; and an aging population coupled with a rapidly shrinking population of individuals under 45 years old, making Santa Fe less attractive to business recruits. The seven industries recommended by the report “represent a good mix for short-, mid-, and long-term economic cultivation.”

See also

Map of New Mexico State and its subdivision: Map of other states:- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming