Chelsea, formerly known as Winnisimmet by the Naumkeag tribe, is a city in Suffolk County, Massachusetts, United States, directly across the Mystic River from Boston. At the 2020 census, Chelsea had a population of 40,787. With a total area of just 2.46 square miles, Chelsea is the smallest city in Massachusetts in terms of total area. It is the second most densely populated city in Massachusetts, behind Somerville, and is the city with the second-highest percentage of Latino residents in Massachusetts, behind Lawrence.

| Name: | Chelsea city |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 25 |

| LSAD Description: | city (suffix) |

| State: | Massachusetts |

| County: | Suffolk County |

| Elevation: | 10 ft (3 m) |

| Total Area: | 2.47 sq mi (6.39 km²) |

| Land Area: | 2.22 sq mi (5.75 km²) |

| Water Area: | 0.25 sq mi (0.64 km²) |

| Total Population: | 40,787 |

| Population Density: | 18,380.80/sq mi (7,097.87/km²) |

| ZIP code: | 02150 |

| Area code: | 617/857 |

| FIPS code: | 2513205 |

| GNISfeature ID: | 0612723 |

| Website: | www.chelseama.gov |

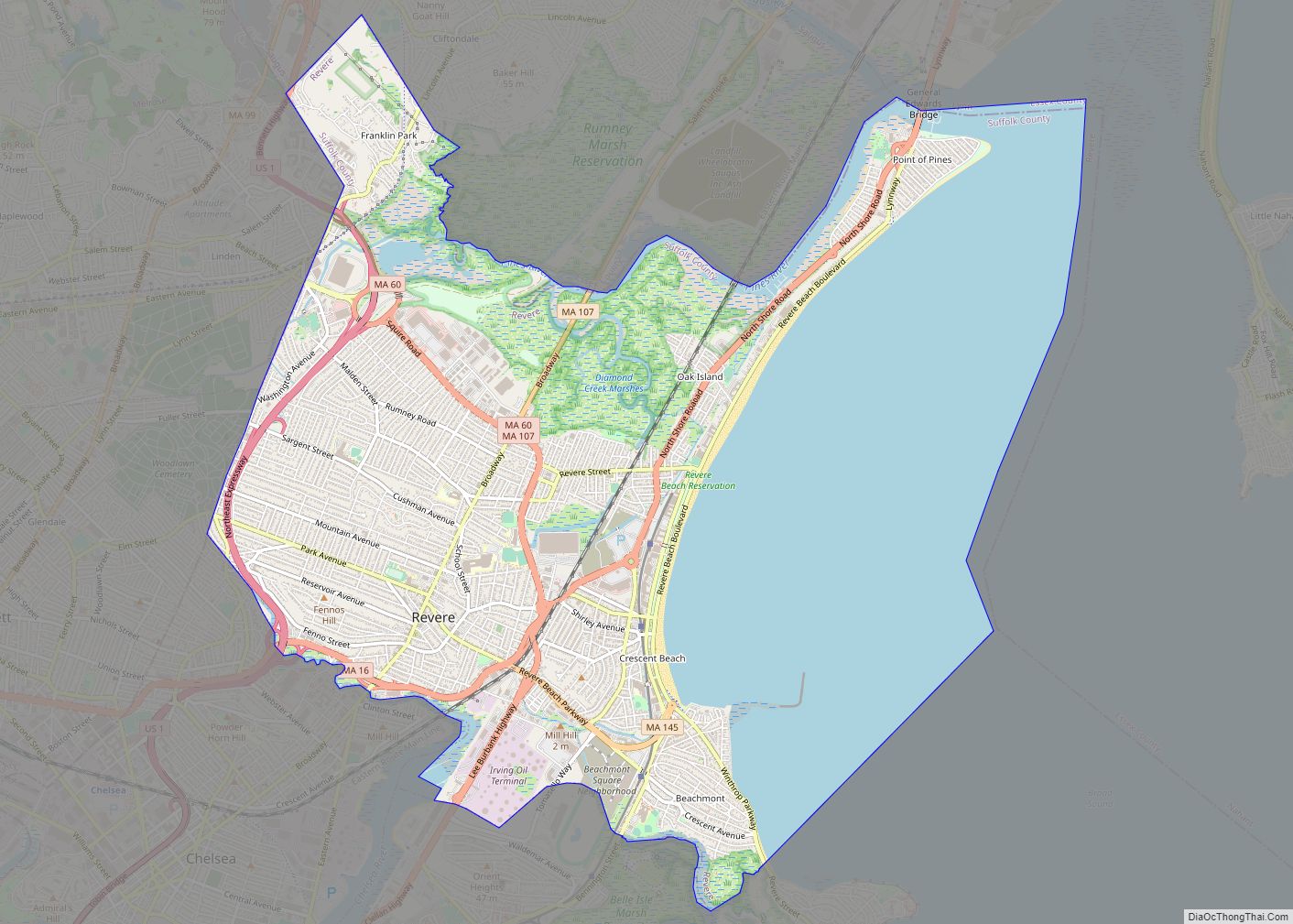

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

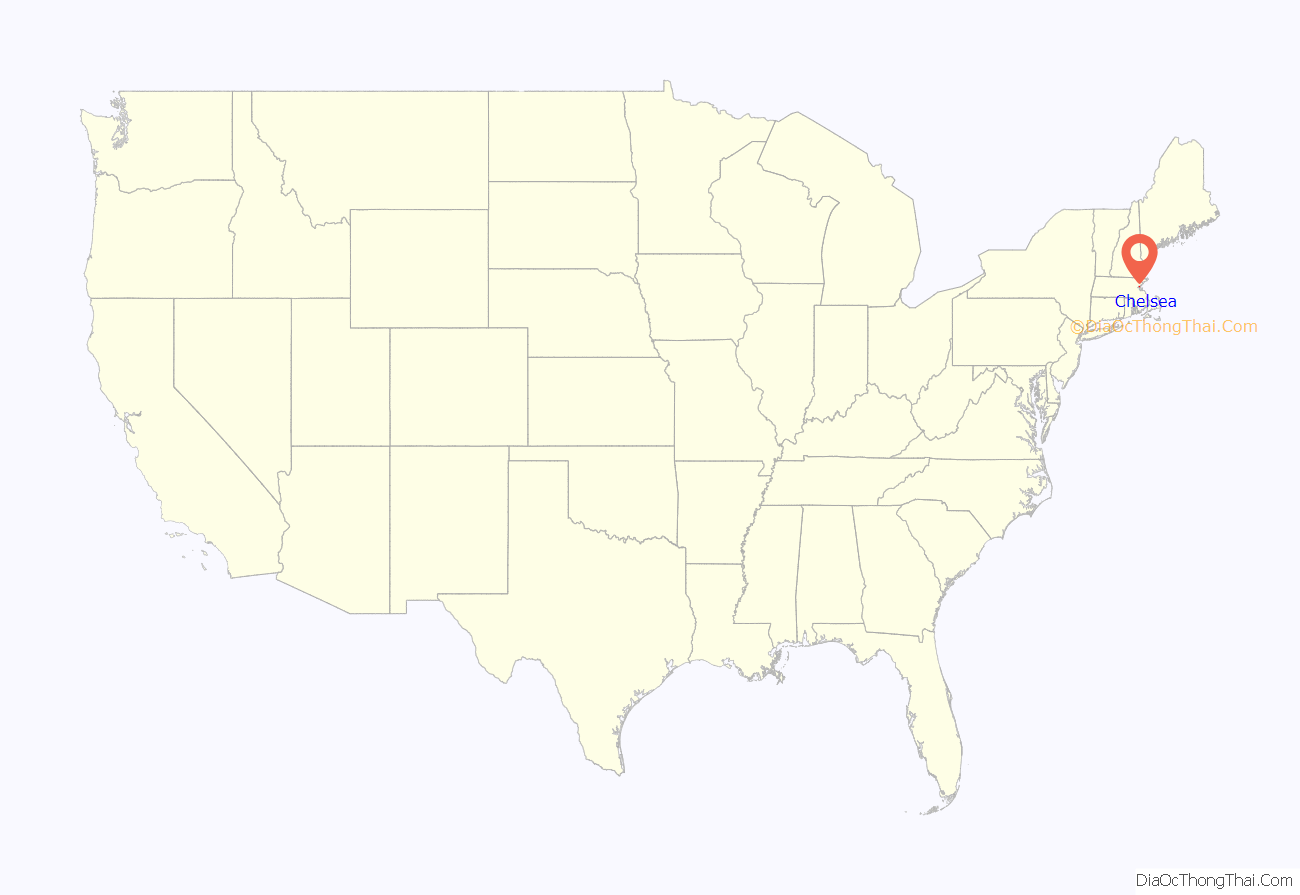

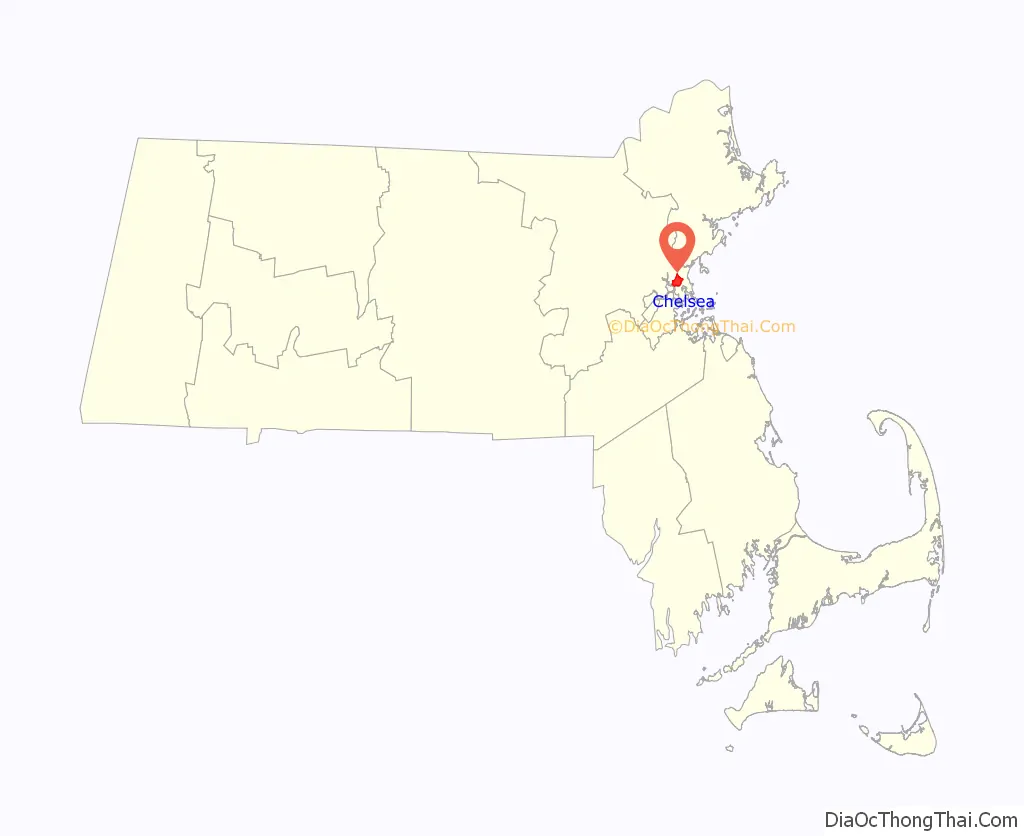

Chelsea location map. Where is Chelsea city?

History

The area of Chelsea was first called Winnisimmet possibly meaning “good spring nearby” or “swamp hill” by the Naumkeag tribe, who lived there for thousands of years prior to European colonization in the 1600s. Samuel Maverick became the first European to settle permanently in Winnisimmet in 1624 and his palisaded trading post is considered the first permanent settlement by Boston Harbor. In 1635, Maverick sold all of Winnisimmet, except for his house and farm, to Richard Bellingham. The community remained part of Boston until it was set off and incorporated in 1739, when it was named after Chelsea, a neighborhood in London, England.

In 1775, the Battle of Chelsea Creek was fought in the area, the second battle of the Revolution, at which American forces made one of their first captures of a British ship. Part of George Washington’s army was stationed in Chelsea during the Siege of Boston.

On February 22, 1841, part of Chelsea was annexed by Saugus, Massachusetts. On March 19, 1846, North Chelsea, which consists of present-day Revere and Winthrop, was established as a separate town. Reincorporated as a city in 1857, Chelsea developed as an industrial center and by mid-century had become a powerhouse in wooden sailing ship construction. As the century wore on, steam power began to overtake the age of the sail and industry in the town began to shift toward manufacturing. Factories making rubber and elastic goods, boots and shoes, stoves, and adhesives began to appear along the banks of Boston Harbor. It became home to the Chelsea Naval Hospital designed by Alexander Parris and home for soldiers.

According to local historical records, Nathan Morse, the first Jewish resident of Chelsea, arrived in 1864, and by 1890 there were only 82 Jews living in the city. However, Chelsea was a major destination for the “great wave” of Russian and Eastern European immigrants, especially Russian Jews, who came to the United States after 1890. By 1910 the number of Jews had grown to 11,225, nearly one third of the entire population of the city. In the 1930s there were about 20,000 Jewish residents in Chelsea out of a total population of almost 46,000. Given the area of the city, Chelsea may well have had the most Jewish residents per square mile of any city outside of New York City.

On April 12, 1908, nearly half the city was destroyed in the first of two great fires that would devastate Chelsea in the 20th century. The fire left 18,000 people, 56 percent of the population, homeless. Despite the magnitude of the destruction, it would only take the city about two and a half years to rebuild and five years to surpass the extent of 1908’s infrastructure. The city was also laid out differently after the fire, with wider streets and more access for emergency vehicles. Many of the city’s residents left and never returned, which opened the door for many immigrants living in Boston to “move up” to Chelsea. To immigrants living in crowded tenements in Boston’s West End, East and South Ends, Chelsea was the next stop on their path of economic upward mobility.

By 1919 Chelsea’s population had reached the record level of 52,662, with foreign-born residents comprising 46 percent of the population. Fully transitioned from a suburb to an industrial city, the waterfront flourished, with shipbuilding, lumberyards, metalworks and paint companies lined Marginal Street.

Between 1940 and 1980, the population declined by 38 percent. Chelsea lost more population than other urban areas after the 1950s because of the construction of the elevated Northeast Expressway built to connect the North Shore suburbs to Boston, via the Mystic River Bridge (later renamed for Boston Mayor Maurice J. Tobin). Hundreds of homes were lost to make way for the expressway as it cut the city in half. The resulting out-migration took with it many small, local businesses. Historic homes were abandoned, along with industrial buildings, brownfields, salt piles and gas storage tanks dotting the cityscape.

In 1973, disaster struck again when the Second Great Chelsea Fire burned 18 city blocks, leaving nearly a fifth of the city in ashes. Both fires originated in Chelsea’s “rag shop district,” cluttered streets filled with junk shops hawking scraps, metal, and combustible items. Wood-frame buildings and three- to six-family houses were built tightly together, and quickly caught fire.

By 1990, Chelsea had collapsed economically and socially. Crime was rampant, even among the police and local government officials. The population drain made way for more immigrants, but depleted the city’s tax base. The cost of running the city and maintaining its infrastructure did not decrease correspondingly so, in 1991, the city suffered fiscal collapse.

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts enacted special legislation to place Chelsea into receivership. For the first time since the Great Depression, a Massachusetts city surrendered home rule and allowed a state-appointed receiver to control all aspects of city government. Governor William Weld named James Carlin as the first receiver followed by Lewis “Harry” Spence. City Hall was eviscerated, the police and fire departments reorganized, management of the public schools given to Boston University, and indictments handed down. Mayor John “Butchie” Brennan and two former mayors were found guilty of federal crimes.

By the summer of 1995, when the state returned City Hall to the people of Chelsea, a new government had been born, brought to life by a panel of citizens charged with drafting a new city charter. The new charter eliminated the position of mayor, converting management of the city from a mayor to a council–manager government system, where a city manager is selected by City Council members. As such, municipal government focused on improving the quality of services provided to residents and businesses, while establishing financial policies that have significantly improved the city’s financial condition. With their leaders more accountable and efficient, Chelsea reversed its long decline and entered a period of population growth and economic development.

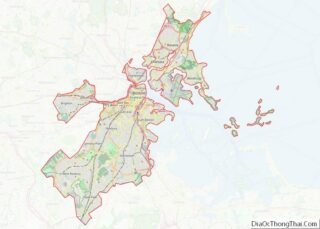

Chelsea Road Map

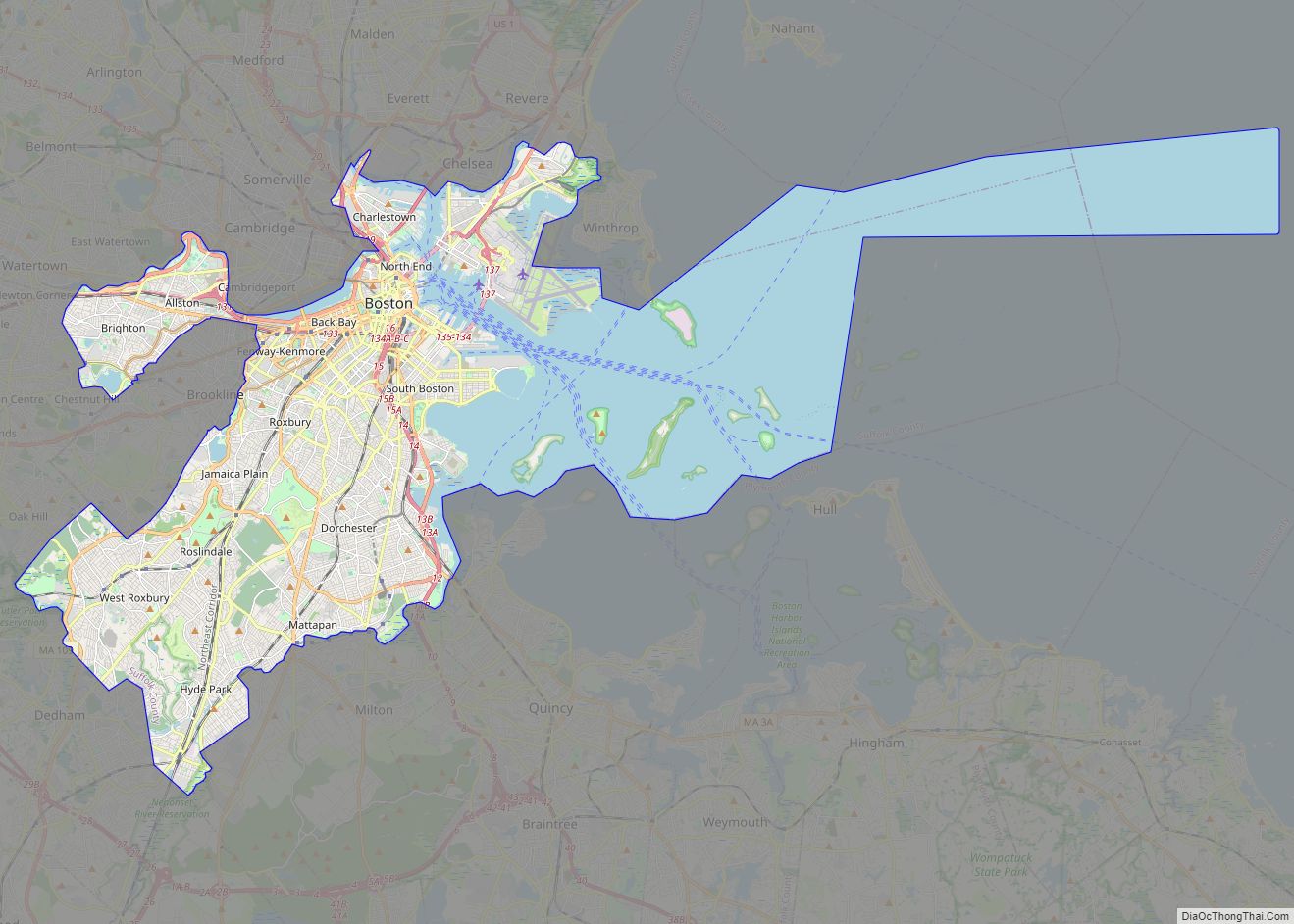

Chelsea city Satellite Map

Geography

Located on a small peninsula in Boston Harbor covering a mere 2.21 square miles (6 km), Chelsea is the smallest city by area in Massachusetts. Chelsea is bordered on three sides by water. The Mystic River borders Chelsea to the southwest, the Chelsea Creek and Mill Creek and the Island End River border it to the west.

The topography of Chelsea consists primarily of coastal lowlands, punctuated by four drumlins formed during the last Ice Age. These drumlins are located in the southwest (Admirals Hill), southeast (Mount Bellingham), northeast (Powderhorn Hill) and northwest (Mount Washington). A smaller drumlin (Mill Hill) is located on the east side of Chelsea, adjacent to Mill Creek. This sloped and hilly landscape helps to divide the city into discernible neighborhoods, each with its own character, thereby giving the city a manageable sense of scale and orientation.

Neighborhoods and districts

Despite its small size, there are several distinct neighborhoods in Chelsea:

Admirals Hill: Admirals Hill sits atop a point of land between the Mystic River and Island End River. Containing the Naval Hospital Historic District, the area is mostly residential development enjoying expansive views. On the south slope of the hill is the site of the historic Chelsea Naval Hospital, with several brick and granite structures that have been converted to other uses. Between the Naval Hospital and the shoreline is the Mary O’Malley Park, the largest public park in Chelsea.

Addison-Orange: Adjacent to the north side of downtown, the Addison-Orange neighborhood is residential, flat and densely populated. Washington Avenue runs through this neighborhood.

Bellingham Square: This historic district became the center of commerce and government after the 1908 fire. The cohesiveness of design is the result of community planning after the Great Fire of 1908. The district includes City Hall, modeled after Old Independence Hall in Philadelphia, the Public Library and Phoenix Charter Academy’s campus.

Box District: Just over a block from City Hall, this once blighted neighborhood gets its name from various box manufacturing companies that operated in the area as early as 1903, when the Russell Box Company began operations at the foot of Gerrish Avenue. Abandoned in the 1960s, the area fell into disrepair until it was rezoned for residential use in the 2000s. It is now the fastest-growing part of Chelsea and has enjoyed a building boom since 2005, with town homes and multifamily housing complexes proliferating in the area.

Carter Park—Wyndham Area: The neighborhood around Carter Park is a small enclave of mostly single-family Queen Anne style homes surrounded by heavy commercial and highly trafficked areas. Route 1 looms above the southeastern edge of this tree-lined neighborhood, and Revere Beach Parkway winds along the northern edge. The Chelsea High School, Floramos, Wyndham Hotel, Boston’s FBI regional field office, MGH Healthcare Center, and Mystic Mall (Market Basket, TJ Maxx, Home Goods, Five Guys) are located in this area. The historic Chelsea Clock Company used to be located in this area until 2015.

Chelsea Square: This historic district located in the downtown area contains the finest and most intact grouping of mid 19th and early 20th century commercial architecture in the city. Area includes a waterfront district (South Broadway neighborhood) with brick row houses dating to the mid to late 19th century. Third Street is also in the area, becoming the industrial Everett Avenue. The Chelsea Police Department is located here.

Chelsea Commons: Formerly known as Parkway Plaza, Chelsea Commons sits on a low flat area near the end of Mill Creek, part of which was on a former landfill and clay pit. The plaza consists of big-box retail, fast-food restaurants, and two large apartment buildings. It is bordered by a strip of wetlands on both sides. Webster Ave, Mill Creek Riverwalk, Creekside Common, and Beth Israel Deaconess HealthCare.

Mill Hill: This largely residential area consists mostly of two- and three-story wood frame detached buildings. Covering the smallest of the city’s drumlins, the Mill Hill neighborhood sits on a small neck of land bounded by Chelsea Creek and Mill Creek. This neighborhood is on the Revere line. Eastern Avenue goes through his neighborhood.

Prattville: Is the northwestern section of the city. It also borders Revere and Everett to the west. Pizza Lovers, Washington Park, Voke Park, and The Newbridge Cafe are located in this area. Metro Credit Union and McDonald’s have a large presence there as well. Next to these chains is another, smaller Chelsea Firefighter station. Garfield and Washington Avenues are in Prattville. Route 1 is on the east side of Prattville, and Route 16 is on the south side.

Soldiers Home: The Soldiers Home neighborhood covers the steep slopes and the peak of Powderhorn Hill. This residential area contains some examples of Queen Anne style architecture. Soldiers Home is one of the least dense neighborhoods in the city. At the peak sits the Soldiers Home, a large structure that dominates much of this area. However, there are some smaller associated brick structures in the area as well as Malone Park.

Waterfront District: For the first time, Chelsea is breaking through the heavy industry piled up along the Chelsea Creek, and reconnecting with its waterfront. Established to promote water-oriented industrial uses at Forbes Industrial Park and the lower Chelsea Creek waterfront, its use remains primarily industrial. Most of the waterfront from the Tobin Bridge to the mouth of Mill Creek is a Designated Port Area (DPA), and Chelsea has in the last decade embraced it. The city is encouraging industry to move in, but only if they help finance a new park on the waterfront.

See also

Map of Massachusetts State and its subdivision: Map of other states:- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming