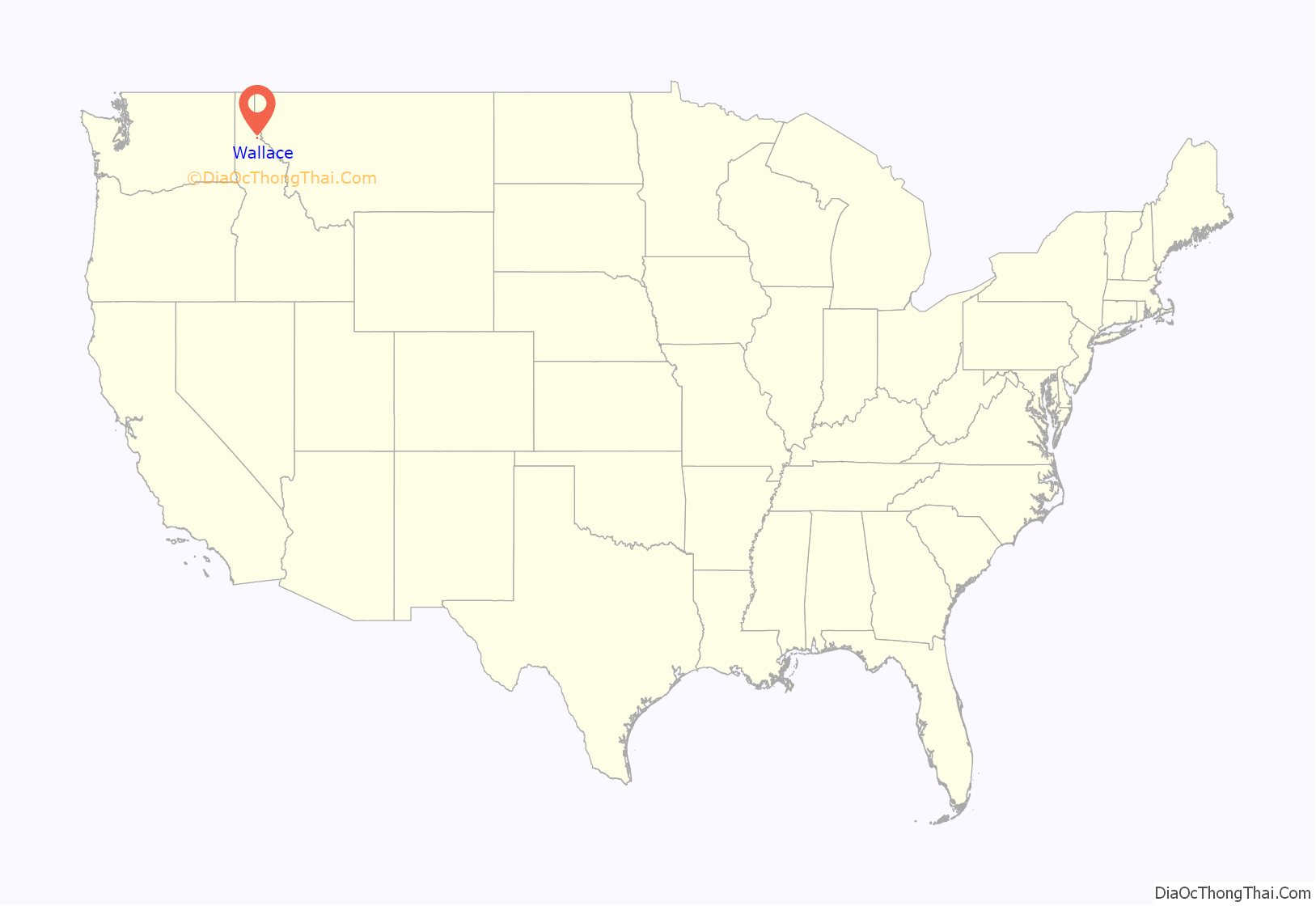

Wallace, Idaho is a city in and the county seat of Shoshone County, Idaho, in the Silver Valley mining district of the Idaho Panhandle. Founded in 1884, Wallace sits alongside the South Fork of the Coeur d’Alene River (and Interstate 90). The town’s population was 784 at the 2010 census.

The Route of the Hiawatha rails-to-trail passes through Wallace.

| Name: | Wallace city |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 25 |

| LSAD Description: | city (suffix) |

| State: | Idaho |

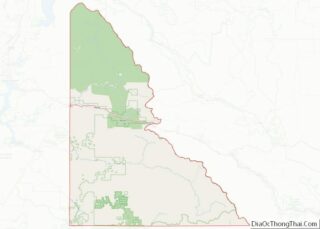

| County: | Shoshone County |

| Founded: | 1884 |

| Elevation: | 2,730 ft (830 m) |

| Total Area: | 0.91 sq mi (2.35 km²) |

| Land Area: | 0.91 sq mi (2.35 km²) |

| Water Area: | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km²) |

| Total Population: | 784 |

| Population Density: | 861.23/sq mi (332.38/km²) |

| ZIP code: | 83873-83874 |

| Area code: | 208, 986 |

| FIPS code: | 1684790 |

| GNISfeature ID: | 392796 |

| Website: | wallace.id.gov |

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

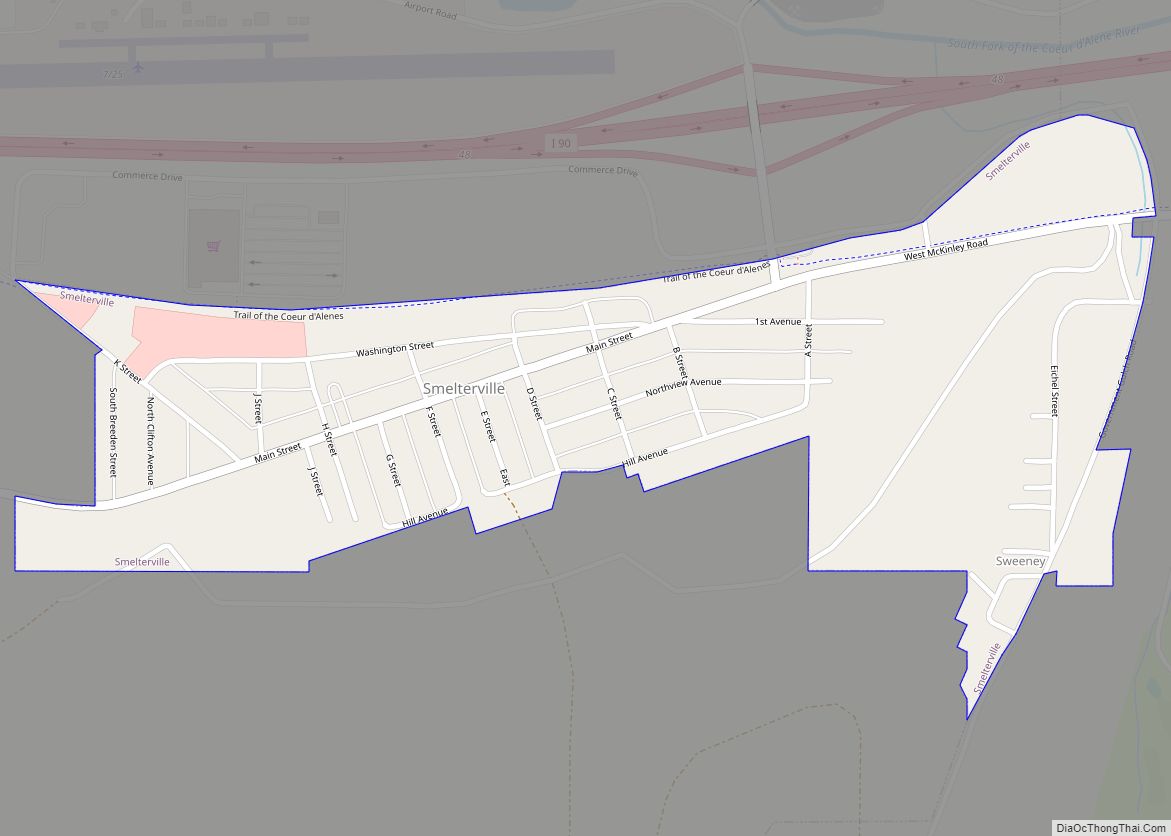

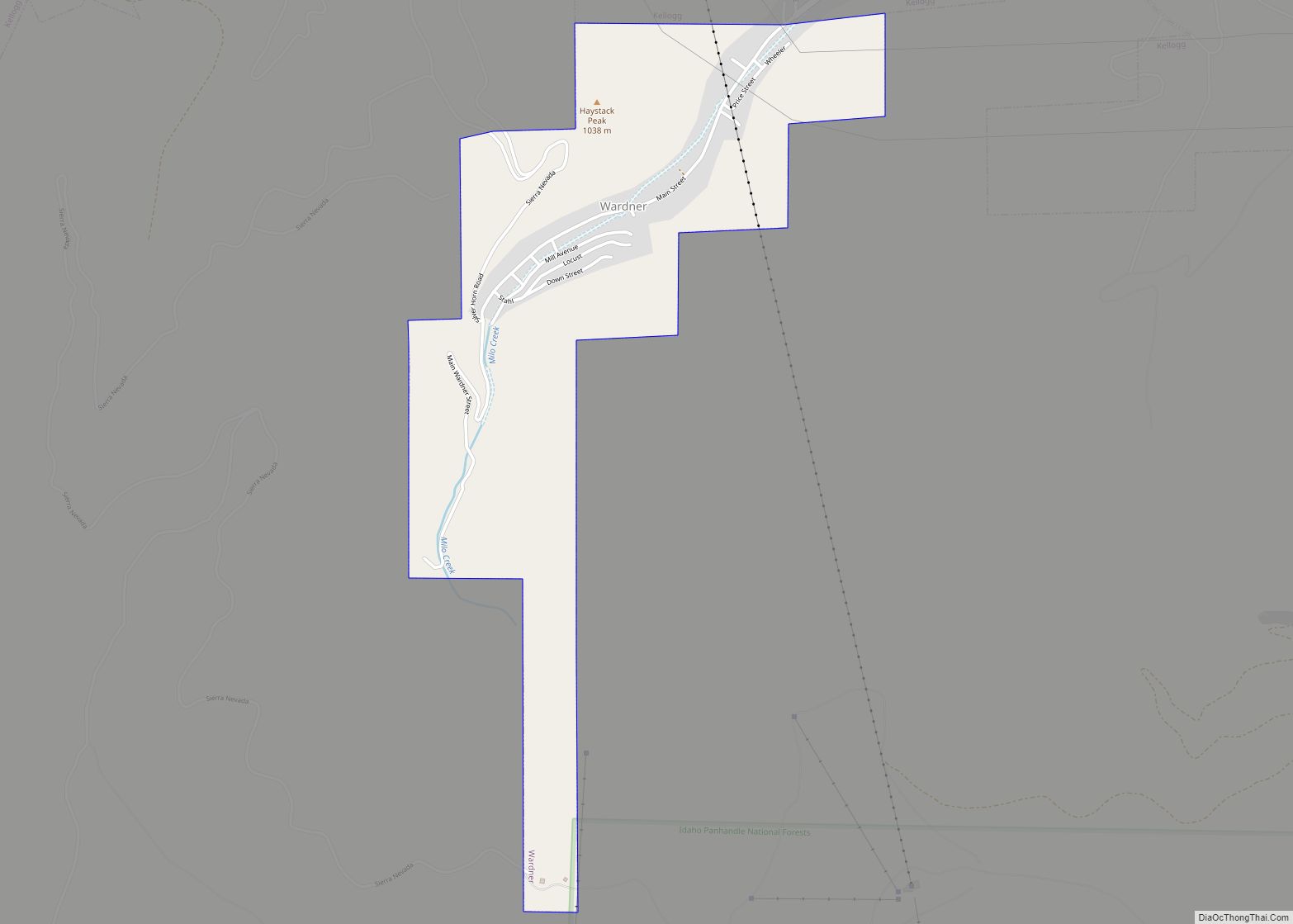

Wallace location map. Where is Wallace city?

History

Gold was discovered in a stream about twelve miles north of the future Wallace in the spring of 1882. Migration to the region increased, especially during the following year. Eagle City, Prichard, Murrayville (now Murray) and other mining camps were founded, and mining claims proliferated. Silver was also discovered.

Founding and early years

In the spring of 1884, Colonel William R. Wallace built a cabin at a site he called “Placer Center.” A Civil War veteran, Wallace was heavily involved in mining ventures after the war. The spot’s central location in the mining district clearly offered promise as a town site. In fact, a news sheet published at the time extolled the town’s favorable prospects because “it is on the Mullan Road, which is the main emigrant road on the Bitter Root divide.” Wallace believed in his new venture and invested money to build access roads, put up lot fences and make other improvements. By the spring of 1885, Placer Center had a grocery store and several other small businesses. Within a year or so, there was also a general store, a sawmill, hotel and more.

Wallace and Richard Lockey bought “Sioux half-breed scrip” from a bank in Spokane, Washington to purchase an 80-acre (32 ha) town site that would become the town of Wallace. Such scrip entitled the holder to “locate” (claim) unoccupied and unsurveyed public lands. Wallace’s application for a land patent to secure title to the townsite was submitted to the General Land Office (GLO) in Coeur d’Alene on June 5, 1886.

The GLO head office in Washington D. C. found that his scrip had been reported lost by its original holder. That original scrip had then been replaced and used to claim land, around six years earlier. For this reason, the GLO denied Wallace’s application, in a letter dated February 3, 1887. Nevertheless, Col. Wallace and his Wallace Townsite Company continued to sell properties (lots) because the Coeur d’Alene land officer had advised them that they could do so. In fact, the officer said he would act as Wallace’s attorney if a dispute arose. Neither the Company nor Col. Wallace informed potential or actual buyers that their patent on the townsite was uncertain.

The settlement flourished, and by the fall of 1887 when its first school was opened, there were many saloons, one brewery, a large apartment building with a public hall, a hotel, and many stores and shops. On September 10, 1887, a narrow gauge rail line reached Wallace, leading to further growth. Within two years the railroad would offer regular scheduled service. On May 2, 1888, a group of citizens petitioned Shoshone County’s county commissioners for the town’s incorporation, now to be called “Wallace”, after the Colonel. Wallace was appointed one of the five trustees of the new town.

In November 1888, the townsite company engaged a Washington, D.C., attorney who specialized in contested public lands cases. The letter reporting this action does not say what event led to the move. However, it asserted that the original scrip owner had “made oath … that he had never parted with the original, and never gave anyone power to use his name in any other location.” That is, the company saw the reported GLO duplication of the scrip as a fraudulent action.

But by February 19, 1889, reports had arrived in Wallace of a case involving disputed Sioux half-breed scrip. The Department of Interior (DOI) denied a Montana land claim because the scrip had been used for the benefit of persons other than the mixed-blood it had been issued to initially. This decision more closely followed the apparent intent of the original legislation, but was actually a reversal of long-standing GLO practice. For decades, the GLO had allowed land dealers to buy the scrip from the mixed-bloods for a pittance and then claim large expanses of valuable public land for white use. One group of speculators made substantial profits from at least 15,000 acres (6,070 ha) of land in Minnesota, Nevada and California. Newspaper reports suggested that this DOI decision might affect land claims in several places across the West.

In Wallace, the news of the case led many townspeople—on the night of Tuesday, February 19, 1889—to participate in “lot jumping,” that is, peremptorily marking the space as their own. Newspapers across the United States carried news of the small western town’s real estate upheaval. The New York Times wrote: “Many persons heretofore considered rich are no longer so, while poor persons have jumped into comfortable circumstances.” Some existing owners guarded their own lots in order to retain their right of ownership. Local historian Judge Richard Magnuson wrote, “By 2 a.m., everything was located and the rush subsided.”

William R. Wallace reacted to the jumping with an angry letter, partially quoted above to describe what the company considered improper action by the GLO. The letter closed, “The higher courts will ere long decide the validity of the claimants.” With this letter and several others, Wallace took the stance of an aggrieved party in relation to the GLO’s handling of the Sioux scrip. It has been documented that the under-staffed and poorly-run GLO was indeed involved in corrupt dealings at that time. Continuing their aggressive stance, the Wallace Townsite Company filed 13 legal suits, demanding $1,000 from citizens it claimed had illegally jumped their properties. Several years passed before all the disputes were fully resolved. Fortunately, land holders who had legitimately developed their plots were able to gain clear title. By the time the disputes were concluded, William R. Wallace had opened an office in Spokane to pursue mining ventures in the West.

In July 1890, a fire aided by strong winds destroyed thirteen saloons, six hotels, a bank, a theater, eighteen office structures (many doctors and lawyers, and the newspaper), three livery stables, and over thirty other stores and shops. A meeting hall, the telephone exchange, and the post office were also destroyed. Following the fire, the town organized a new, better-equipped fire company, installed an improved water system, and adopted ordinances requiring fireproof construction in certain downtown areas.

Labor strife, 1892 and 1899

In 1892, mine owners in the Coeur d’Alenes found the usual investor pressure for profits exacerbated by increased railroad freight rates. Their subsequent measures to cut costs sparked a strike by the mine workers, so the operators brought in replacements. The pressure finally sparked the Coeur d’Alene, Idaho labor strike of 1892, which ended in a union victory. The immediate costs were three men dead on each side and the total destruction of the Frisco ore mill, about four miles northeast of Wallace.

Unfortunately, the violence did not end there. An armed mob attacked the replacement workers as they waited for river transport out to Coeur d’Alene City. No evidence was found that the union leadership sanctioned this brutality, but reports to Idaho Governor Willey said that a dozen bullet-riddled bodies had been found. Martial law was declared and lasted about four months, but none of the charges brought by authorities were upheld.

A similar, although not nearly so deadly confrontation occurred in April 1899. It again began among the miners working northeast of Wallace. However, the union’s target was the Bunker Hill & Sullivan Mining Company, which adamantly refused to recognize or deal with the miners’ union. A huge force took over and blew up the company’s mill at Wardner. During the Coeur d’Alene, Idaho labor confrontation of 1899 attackers murdered a non-union miner and killed one of their own by “friendly fire.”

Alarmed by the size of attacking force – perhaps as many as a thousand men – Governor Frank Steunenberg imposed martial law. About a thousand men were rounded up and held in a crude prison, dubbed “the bullpen.” But in the end, only one union man was convicted of a crime, and he was pardoned and released two years later. But, again, there was a tragic aftermath. In 1905, union assassin Harry Orchard murdered ex-Governor Steunenberg.

Wallace grows

In 1893, Wallace went from governance by a board of trustees to a city charter. The first official mayor was William S. Haskins, who would shortly thereafter be appointed as Idaho’s first State Mining Inspector. Haskins was succeeded by Oscar Wallace, son of Colonel Wallace. By that year, Wallace could also boast of the Providence Hospital, “an institution which has no equal of its kind in the state of Idaho, and no superior of its size in the United States.”

In 1898, having experienced explosive growth, the city implemented a campaign to become the county seat for Shoshone County. A similar attempt six years earlier had left Wallace a distant third to Murray. This time around, Wallace garnered about three-quarters of the votes cast.

The year 1900 saw Wallace residents looking forward to even more growth from its population of over two thousand. They were proud of their extensive electric light system, substantial amounts of paved streets and the most building activity the city had ever seen.

However, one third of the town of Wallace was destroyed by the Great Fire of 1910, which burned about 3,000,000 acres (12,141 km; 4,688 sq mi) in Washington, Idaho, and Montana. Although set back by the devastation, the city soon resumed its growth, aided by strong demand for lead during World War I. After a post-war lull, the industry resumed its growth in the 1920s.

Famous for vice

A mining community with a “work hard, play hard” attitude, Wallace became well known for a permissive approach toward drinking, gambling and decriminalized prostitution. From 1884 to 1991, illegal yet regulated brothel-based sex work openly flourished because locals believed that sex work prevented rape and bolstered the economy, so long as it was regulated and confined to the northeastern part of town. Throughout the rest of the country, progressive era politics drove red-light districts underground, but madams in Wallace enjoyed unprecedented status as influential businesswomen, community leaders, and philanthropists. Between 1940 and 1960, for example, an average of 30 to 60 women came into town to work in one of the five well-established brothels.

Pollution versus jobs

By around 1930, residents downstream from the Coeur d’Alene mines were complaining about water and air pollution. Operators downplayed the issue, but did make a few process concessions. Then the ravages of the Great Depression virtually eliminated the issue for the duration. That was followed by the ramp-up to World War II, which further kept the problems in the background. After the war, the metals industry in the region boomed, reaching a peak by around 1965. Process improvements continued but could not totally alleviate the effluent problems. And practically nothing was done about a half-century of pollution buildup.

Beginning in 1955, the U. S. Congress passed a series of air pollution laws, culminating in the Clean Air Act of 1970. That was followed two years later by the Federal Water Pollution Control Act. That and creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) put heavy pressure on mining operations, including those in the Coeur d’Alenes. When the Bunker Hill smelter in Kellogg shut down in 1981, the Silver Valley lost a vast number of jobs, three-quarters of all the regional mining employment by some estimates. Wallace suffered huge cutbacks just like all the other towns in the area. Only the Lucky Friday mine, located about seven miles east of Wallace, near Mullan, remains in operation at this time.

Historic preservation

Through the period of mine closures, Wallace had troubles of its own. In 1956, the Federal government authorized the Interstate Highway System and construction got under way. Then city leaders in Wallace learned that plans for Interstate 90 in Idaho would virtually wipe out the entire downtown. Their response is outlined in a section below. But the key event occurred in 1979, when several blocks of downtown Wallace were listed on the National Register of Historic Places as a historic district, the Wallace Historic District.

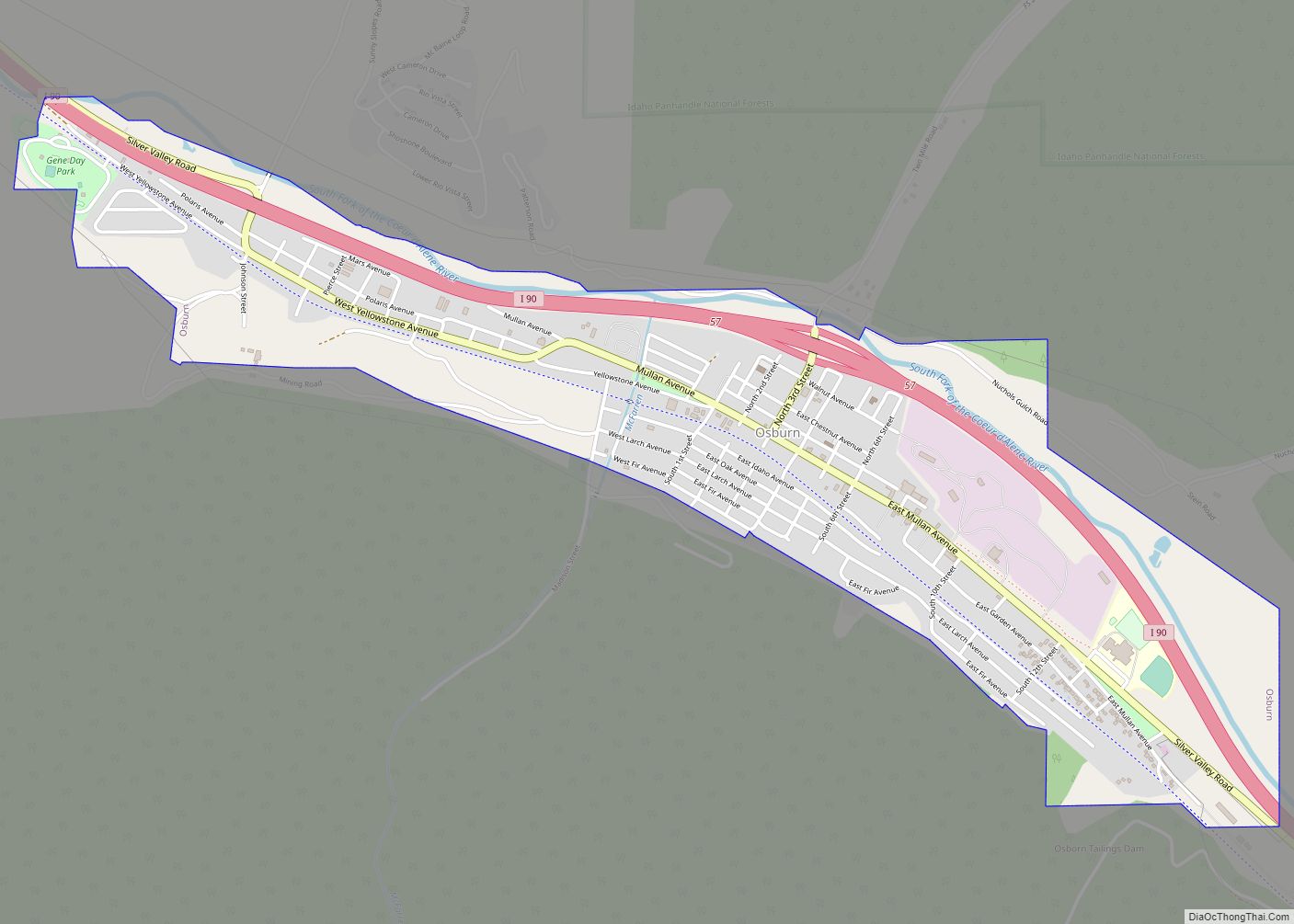

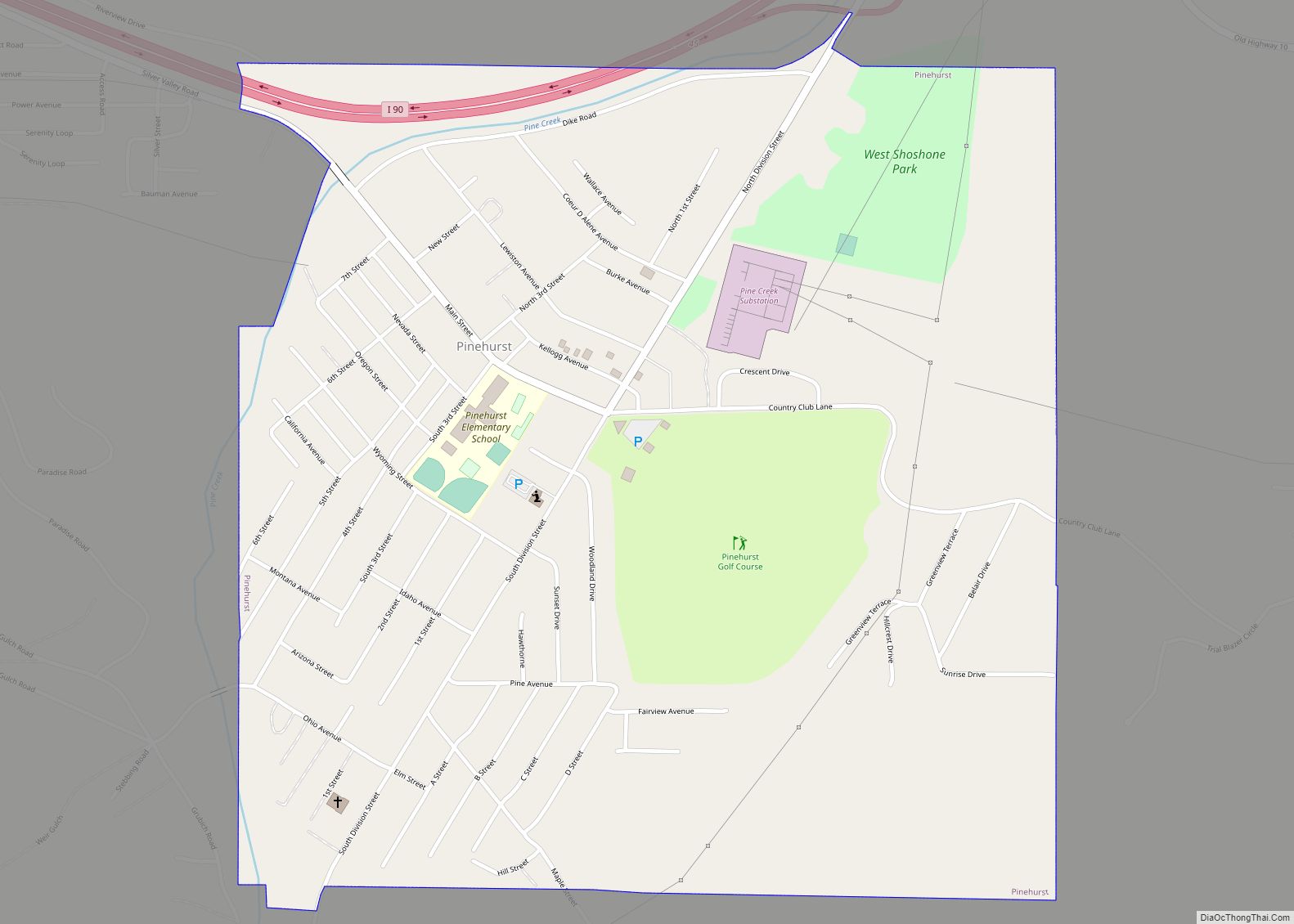

Wallace Road Map

Wallace city Satellite Map

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 0.84 square miles (2.18 km), all of it land.

Climate

Wallace has a continental Mediterranean climate (Köppen Dsb) with warm summers and cold, snowy winters. Winters are relatively moderate for an inland location so far north, although heavy rainfall often occurs when mild Pacific air penetrates inland, as in January 1974 when 14.56 inches (369.8 mm) of precipitation occurred including 3.07 inches (78.0 mm) on the 16th. July 1973 to June 1974 was also the wettest “rain year”, receiving 56.27 inches or 1,429.3 millimetres, whilst the driest rain year from July 2000 to June 2001 saw only 21.96 inches or 557.8 millimetres. The most snowfall has been 91.0 inches (2.31 m) in January 1969; July 1968 to June 1969 also saw the maximum annual snowfall at 167.0 inches or 4.24 metres.

When cold air comes from Canada, temperatures can become severe, with the record low being −31 °F or −35 °C on December 30, 1968. The coldest month since records began in 1941 has been January 1949 with an average of 10.5 °F or −11.9 °C; the hottest has been July 2007 with a daily mean of 73.2 °F or 22.9 °C and a mean maximum of 91.1 °F or 32.8 °C.

See also

Map of Idaho State and its subdivision:- Ada

- Adams

- Bannock

- Bear Lake

- Benewah

- Bingham

- Blaine

- Boise

- Bonner

- Bonneville

- Boundary

- Butte

- Camas

- Canyon

- Caribou

- Cassia

- Clark

- Clearwater

- Custer

- Elmore

- Franklin

- Fremont

- Gem

- Gooding

- Idaho

- Jefferson

- Jerome

- Kootenai

- Latah

- Lemhi

- Lewis

- Lincoln

- Madison

- Minidoka

- Nez Perce

- Oneida

- Owyhee

- Payette

- Power

- Shoshone

- Teton

- Twin Falls

- Valley

- Washington

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming