Fairbanks is a home rule city and the borough seat of the Fairbanks North Star Borough in the U.S. state of Alaska. Fairbanks is the largest city in the Interior region of Alaska and the second largest in the state. The 2020 Census put the population of the city proper at 32,515 and the population of the Fairbanks North Star Borough at 95,655, making it the second most populous metropolitan area in Alaska after Anchorage. The Metropolitan Statistical Area encompasses all of the Fairbanks North Star Borough and is the northernmost Metropolitan Statistical Area in the United States, located 196 miles (315 kilometers) by road (140 mi or 230 km by air) south of the Arctic Circle.

Fairbanks is home to the University of Alaska Fairbanks, the founding campus of the University of Alaska system.

| Name: | Fairbanks city |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 25 |

| LSAD Description: | city (suffix) |

| State: | Alaska |

| County: | Fairbanks North Star Borough |

| Incorporated: | November 10, 1903 |

| Elevation: | 446 ft (136 m) |

| Land Area: | 31.75 sq mi (82.2 km²) |

| Water Area: | 0.88 sq mi (2.3 km²) |

| Population Density: | 1,024.22/sq mi (395.45/km²) |

| Area code: | 907 |

| FIPS code: | 0224230 |

| GNISfeature ID: | 1401958 |

| Website: | www.fairbanksalaska.us |

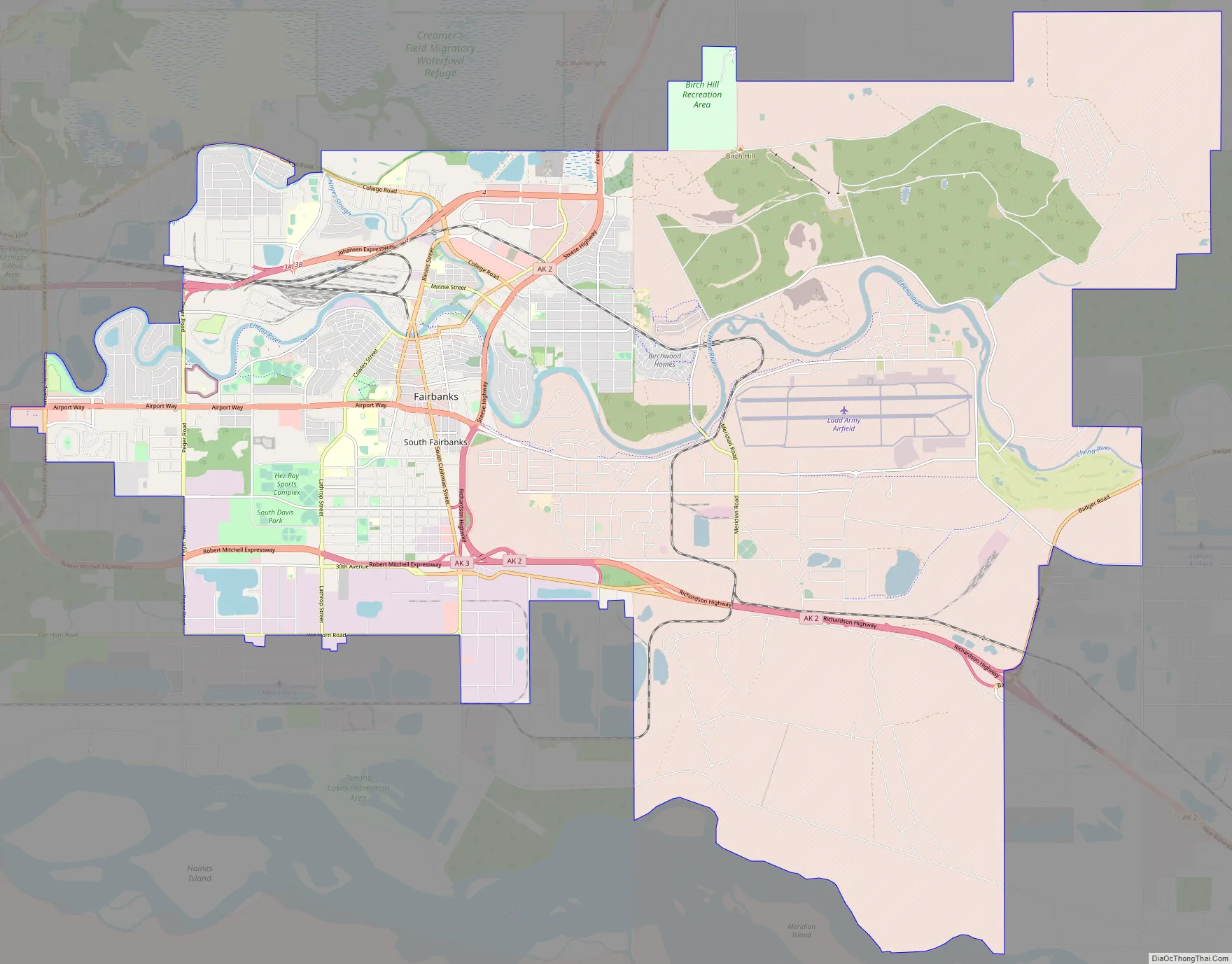

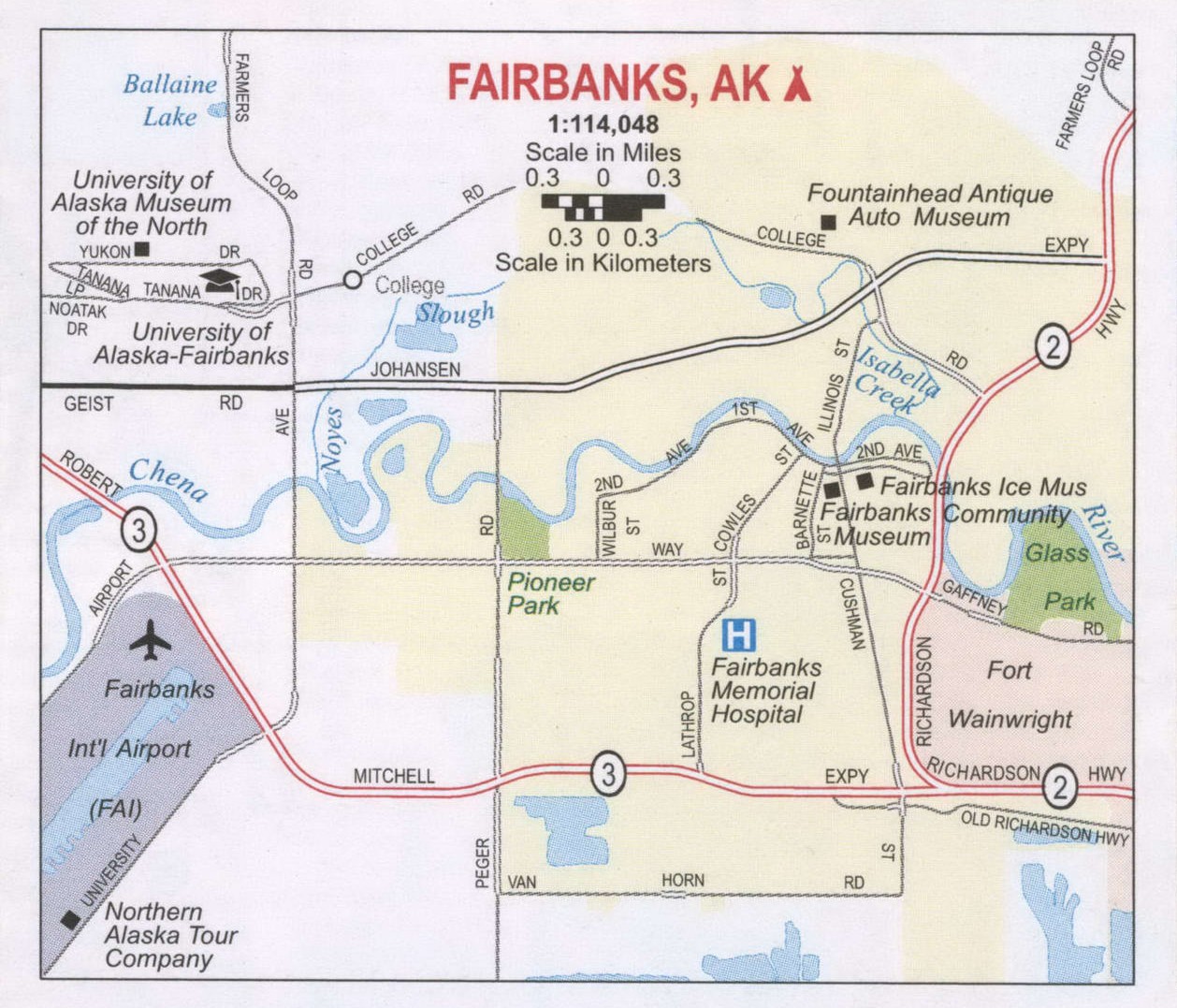

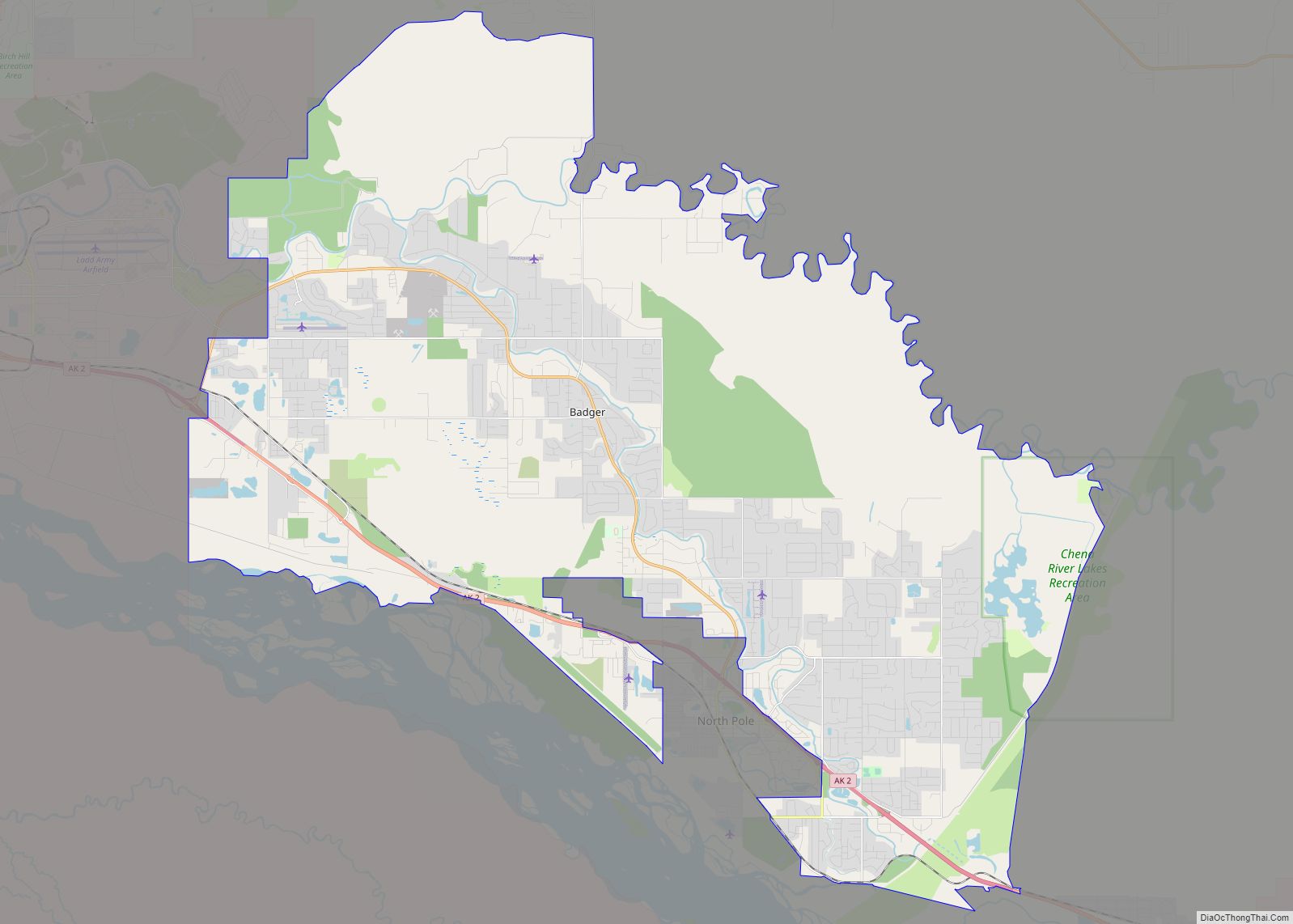

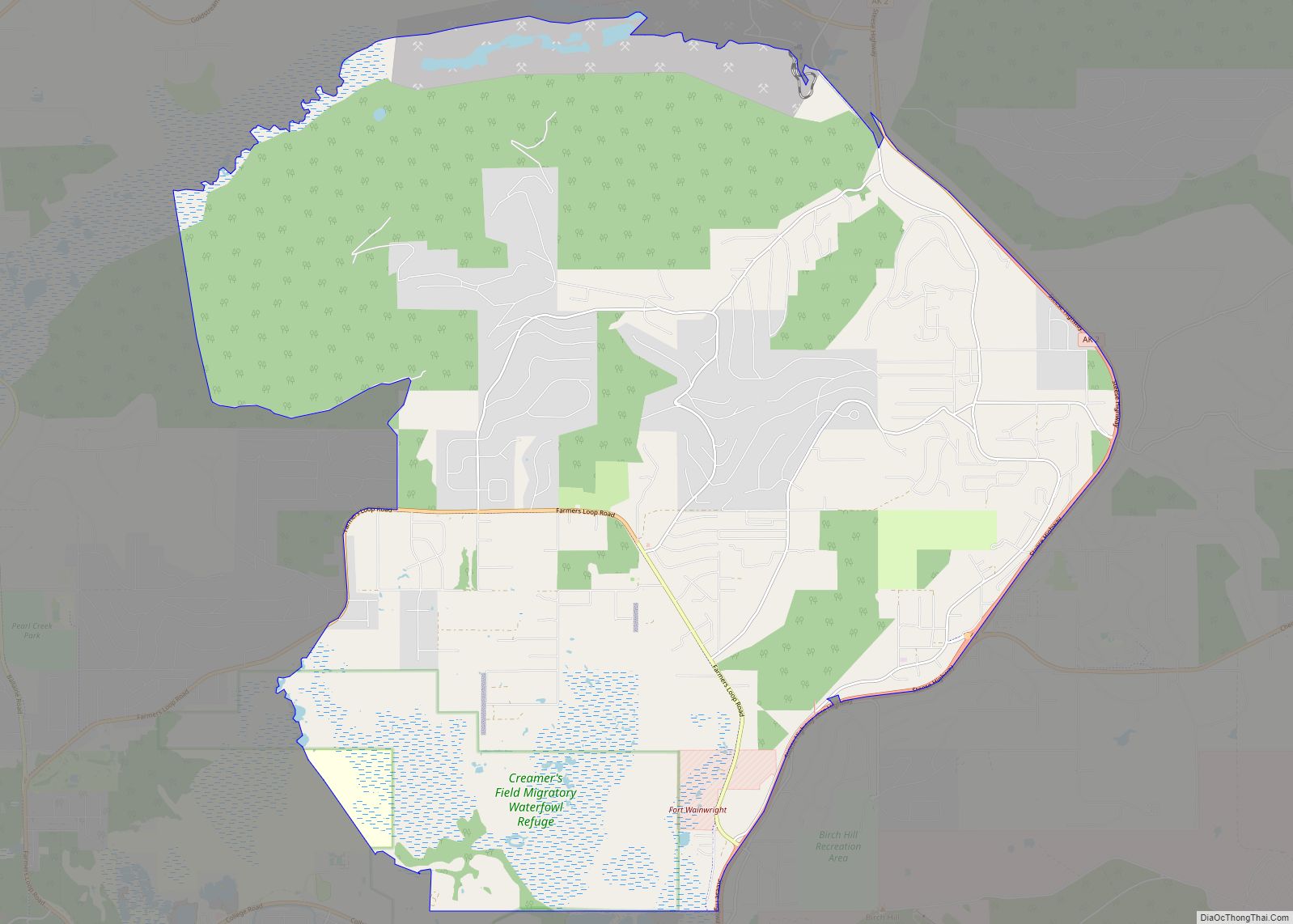

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

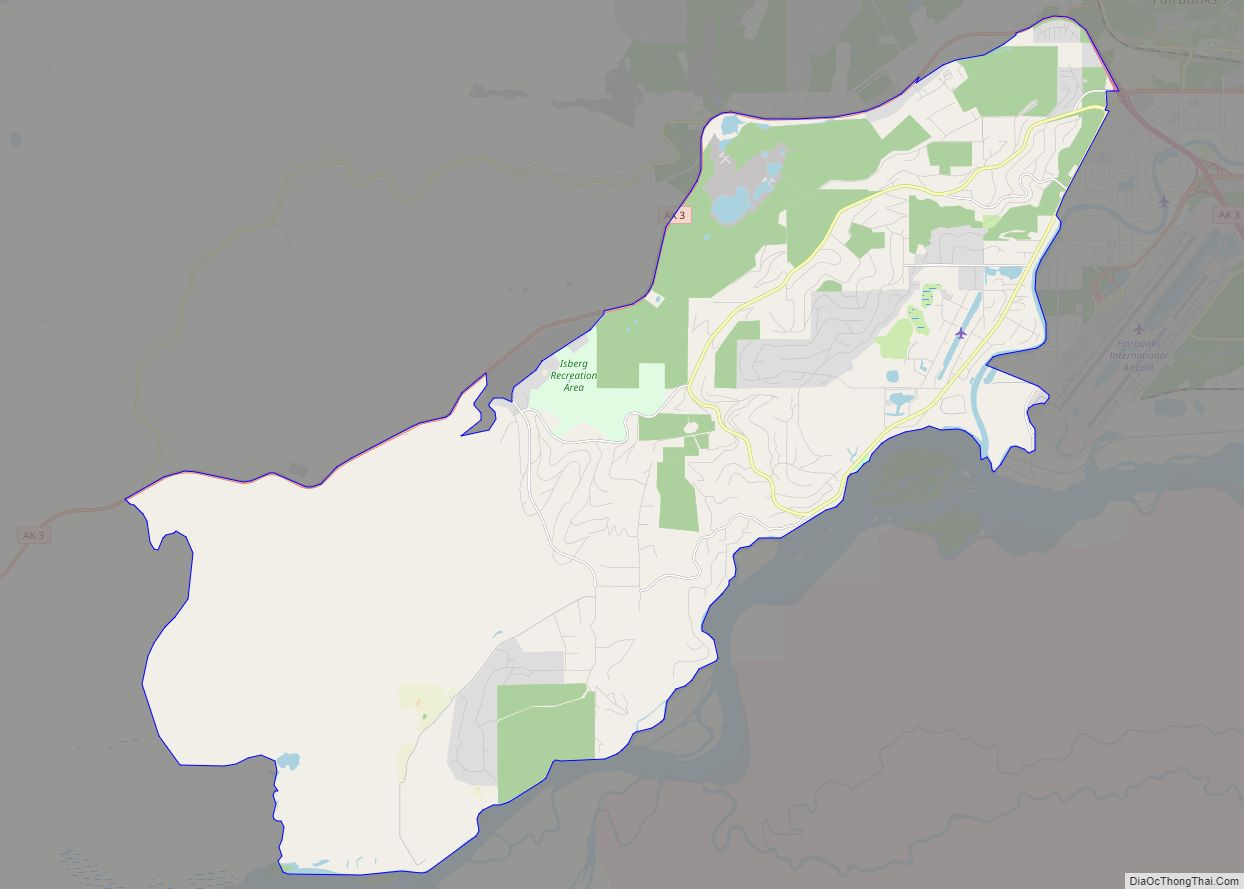

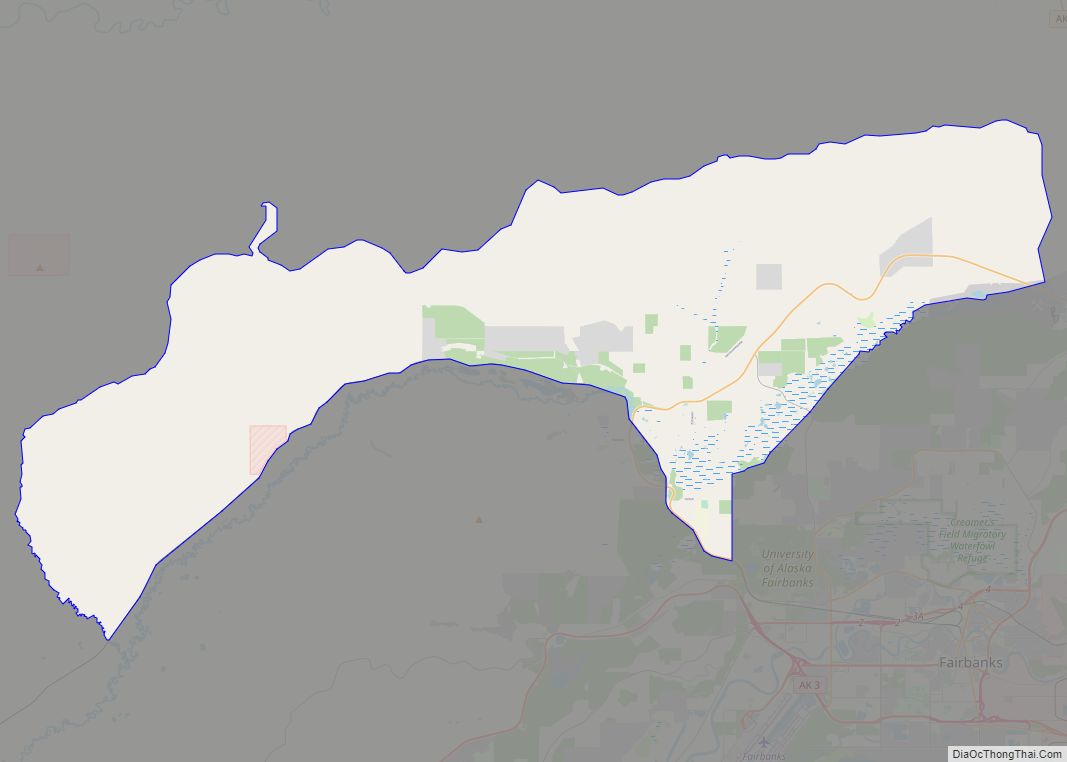

Fairbanks location map. Where is Fairbanks city?

History

Native American presence

Athabascan peoples have used the area for thousands of years, although there is no known permanent Alaska Native settlement at the site of Fairbanks. An archaeological site excavated on the grounds of the University of Alaska Fairbanks uncovered a Native camp about 3,500 years old, with older remains found at deeper levels. From evidence gathered at the site, archaeologists surmise that Native activities in the area were limited to seasonal hunting and fishing as frigid temperatures precluded berry gathering. In addition, archaeological sites on the grounds of nearby Fort Wainwright date back well over 10,000 years. Arrowheads excavated from the University of Alaska Fairbanks site matched similar items found in Asia, providing some of the first evidence that humans arrived in North America via the Bering Strait land bridge in deep antiquity.

European settlers

Captain E. T. Barnette founded Fairbanks in August 1901 while headed to Tanacross (or Tanana Crossing, where the Valdez–Eagle trail crossed the Tanana River), where he intended to set up a trading post. The steamboat on which Barnette was a passenger, the Lavelle Young, ran aground while attempting to negotiate shallow water. Barnette, along with his party and supplies, were deposited along the banks of the Chena River 7 miles (11 km) upstream from its confluence with the Tanana River. The sight of smoke from the steamer’s engines caught the attention of gold prospectors working in the hills to the north, most notably an Italian immigrant named Felice Pedroni (better known as Felix Pedro) and his partner Tom Gilmore. The two met Barnette where he disembarked and convinced him of the potential of the area. Barnette set up his trading post at the site, still intending to eventually make it to Tanacross. Teams of gold prospectors soon congregated in and around the newly founded Fairbanks; they built drift mines, dredges, and lode mines in addition to panning and sluicing.

After some urging by James Wickersham, who later moved the seat of the Third Division court from Eagle to Fairbanks, the settlement was named after Charles W. Fairbanks, a Republican senator from Indiana and later the twenty-sixth vice president of the United States, serving under Theodore Roosevelt during his second term.

In these early years of settlement, the Tanana Valley was an important agricultural center for Alaska until the establishment of the Matanuska Valley Colonization Project and the town of Palmer in 1935. Agricultural activity still occurs today in the Tanana Valley, but mostly to the southeast of Fairbanks in the communities of Salcha and Delta Junction. During the early days of Fairbanks, its vicinity was a major producer of agricultural goods. What is now the northern reaches of South Fairbanks was originally the farm of Paul J. Rickert, who came from nearby Chena in 1904 and operated a large farm until his death in 1938. Farmers Loop Road and Badger Road, loop roads north and east (respectively) of Fairbanks, were also home to major farming activity. Badger Road is named for Harry Markley Badger, an early resident of Fairbanks who later established a farm along the road and became known as “the Strawberry King”. Ballaine and McGrath Roads, side roads of Farmers Loop Road, were also named for prominent local farmers, whose farms were in the immediate vicinity of their respective namesake roads. Despite early efforts by the Alaska Loyal League, the Tanana Valley Agriculture Association and William Fentress Thompson, the editor-publisher of the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, to encourage food production, agriculture in the area was never able to fully support the population, although it came close in the 1920s.

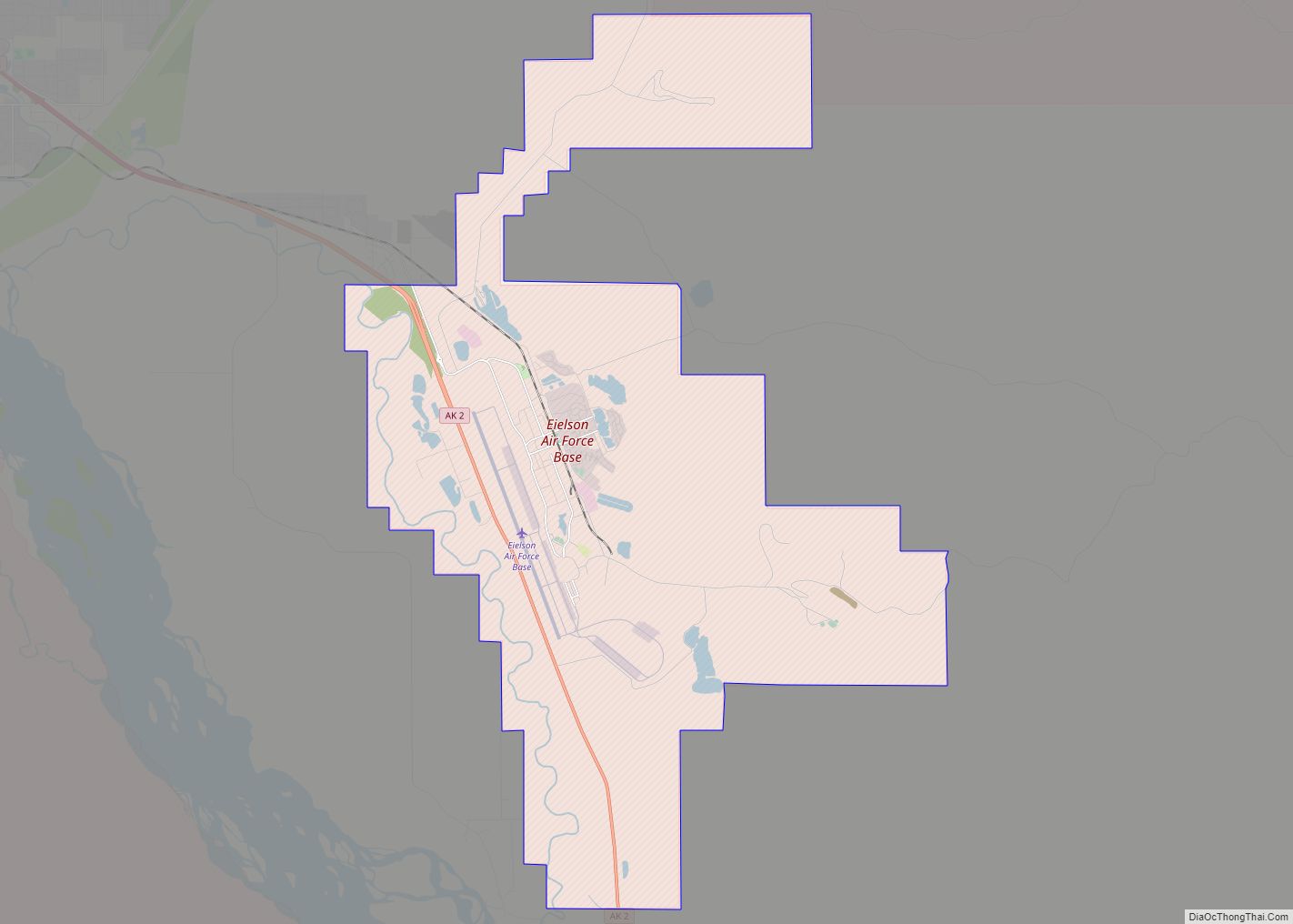

The construction of Ladd Army Airfield starting in 1939, part of a larger effort by the federal government during the New Deal and World War II to install major infrastructure in the territory for the first time, fostered an economic and population boom in Fairbanks which extended beyond the end of the war. In the 1940s the Canol pipeline extended north from Whitehorse for a few years. The Haines – Fairbanks 626 mile long 8″ petroleum products pipeline was constructed during the period 1953-55. The presence of the U.S. military has remained strong in Fairbanks. Ladd became Fort Wainwright in 1960; the post was annexed into Fairbanks city limits during the 1980s.

Fairbanks suffered from several floods in its first seven decades, whether from ice jams during spring breakup or heavy rainfall. The first bridge crossing the Chena River, a wooden structure built in 1904 to extend Turner Street northward to connect with the wagon roads leading to the gold mining camps, often washed out before a permanent bridge was constructed at Cushman Street in 1917 by the Alaska Road Commission. On August 14, 1967, after record rainfall upstream, the Chena began to surge over its banks, flooding almost the entire town of Fairbanks overnight. This disaster led to the creation of the Chena River Lakes Flood Control Project, which built and operates the 50-foot-high (15 m) Moose Creek Dam in the Chena River and accompanying 8-mile-long (13 km) spillway. The project was designed to prevent a repetition of the 1967 flood by being able to divert water in the Chena upstream from Fairbanks into the Tanana River, thus bypassing the city.

Railroad history

After large-scale gold mining began north of Fairbanks, miners wanted to build a railroad from the steamboat docks on the Chena River to the mine sites in the hills north of the city. The result was the Tanana Mines Railroad, which started operations in September 1905, using what had been the first steam locomotive in the Yukon Territory. In 1907, the railroad was reorganized and named the Tanana Valley Railroad. The railroad continued expanding until 1910, when the first gold boom began to falter and the introduction of automobiles into Fairbanks took business away from the railroad. Despite these problems, railroad backers envisioned a rail line extending from Fairbanks to Seward on the Gulf of Alaska, home to the Alaska Central Railway.

In 1914, the US Congress appropriated $35 million for construction of the Alaska Railroad system, but work was delayed by the outbreak of World War I. Three years later, the Alaska Railroad purchased the Tanana Valley Railroad, which had suffered from the wartime economic problems. Rail workers built a line extending northwest from Fairbanks, then south to Nenana, where President Warren G. Harding hammered in the ceremonial final spike in 1923. The rail yards of the Tanana Valley Railroad were converted for use by the Alaska Railroad, and Fairbanks became the northern end of the line and its second-largest depot.

From 1923 to 2004, the Alaska Railroad’s Fairbanks terminal was in downtown Fairbanks, just north of the Chena River. In May 2005, the Alaska Railroad opened a new terminal northwest of downtown, and that terminal is in operation today. In summer, the railroad operates tourist trains to and from Fairbanks, and it operates occasional passenger trains throughout the year. The majority of its business through Fairbanks is freight. The railroad is planning an expansion of the rail line from Fairbanks to connect the city via rail with Delta Junction, about 100 miles (160 km) southeast.

Road history

As the transportation hub for Interior Alaska, Fairbanks features extensive road, rail, and air connections to the rest of Alaska and Outside. At Fairbanks’ founding, the only way to reach the new city was via steamboat on the Chena River. In 1904, money intended to improve the Valdez-Eagle Trail was diverted to build a branch trail, giving Fairbanks its first overland connection to the outside world. The resulting Richardson Highway was created in 1910 after Gen. Wilds P. Richardson upgraded it to a wagon road. In the 1920s, it was improved further and made navigable by automobiles, but it was not paved until 1957.

Fairbanks’ road connections were improved in 1927, when the 161-mile (259 km) Steese Highway connected the city to the Yukon River at the gold-mining community of Circle. In 1942, the Alaska Highway connected the Richardson Highway to the Canadian road system, allowing road travel from the rest of the United States to Fairbanks, which is considered the unofficial end of the highway. Because of World War II, civilian traffic was not permitted on the highway until 1948.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, a series of roads were built to connect Fairbanks to the oil fields of Prudhoe Bay. The Elliott Highway was built in 1957 to connect Fairbanks to Livengood, southern terminus of the Dalton Highway, which ends in Deadhorse on the North Slope. West of the Dalton intersection, the Elliott Highway extends to Manley Hot Springs on the Tanana River. To improve logistics in Fairbanks during construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, the George Parks Highway was built between Fairbanks and Palmer in 1971.

Until 1940, none of Fairbanks’ surface streets were paved. The outbreak of World War II interrupted plans to pave most of the city’s roads, and a movement toward large-scale paving did not begin until 1953, when the city paved 30 blocks of streets. During the late 1950s and the 1960s, the remainder of the city’s streets were converted from gravel roads to asphalt surfaces. Few have been repaved since that time; a 2008 survey of city streets indicated the average age of a street in Fairbanks was 31 years.

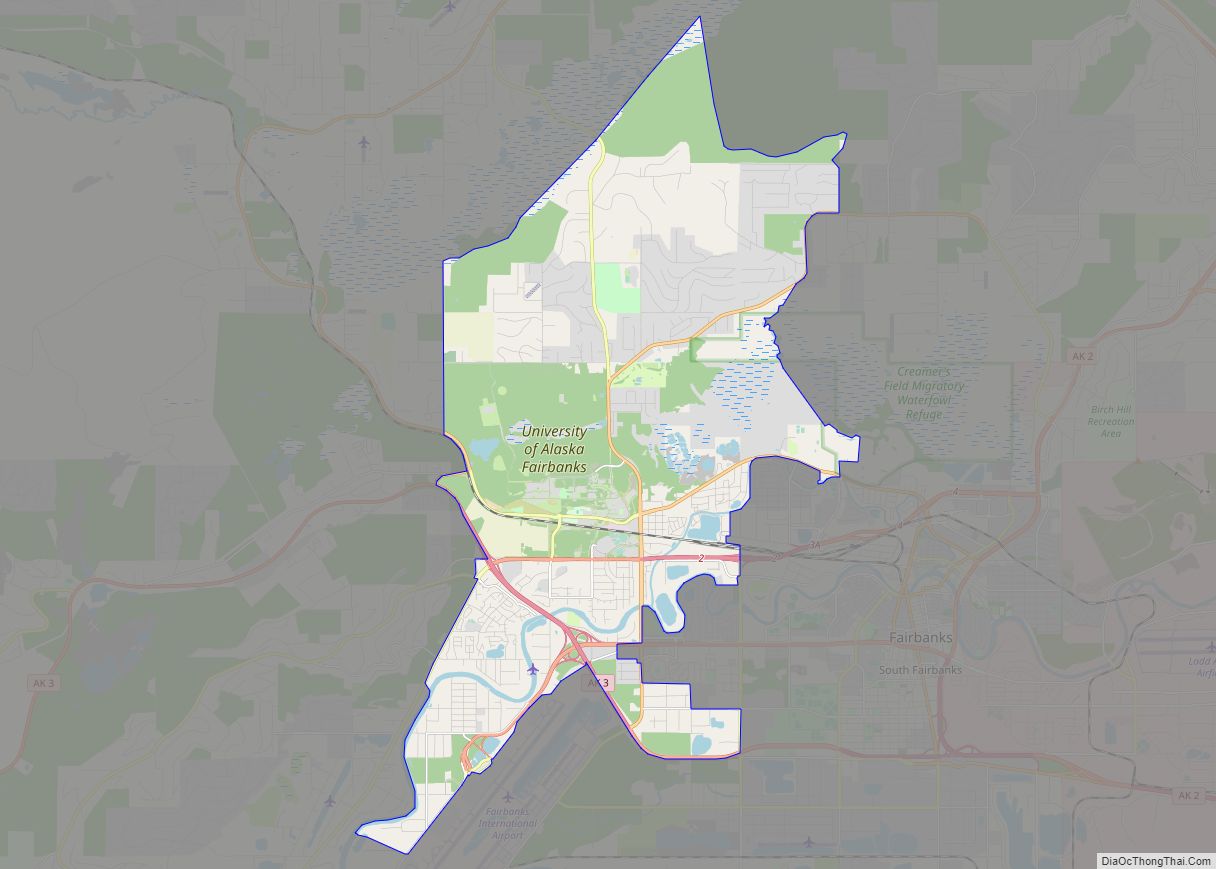

Fairbanks Road Map

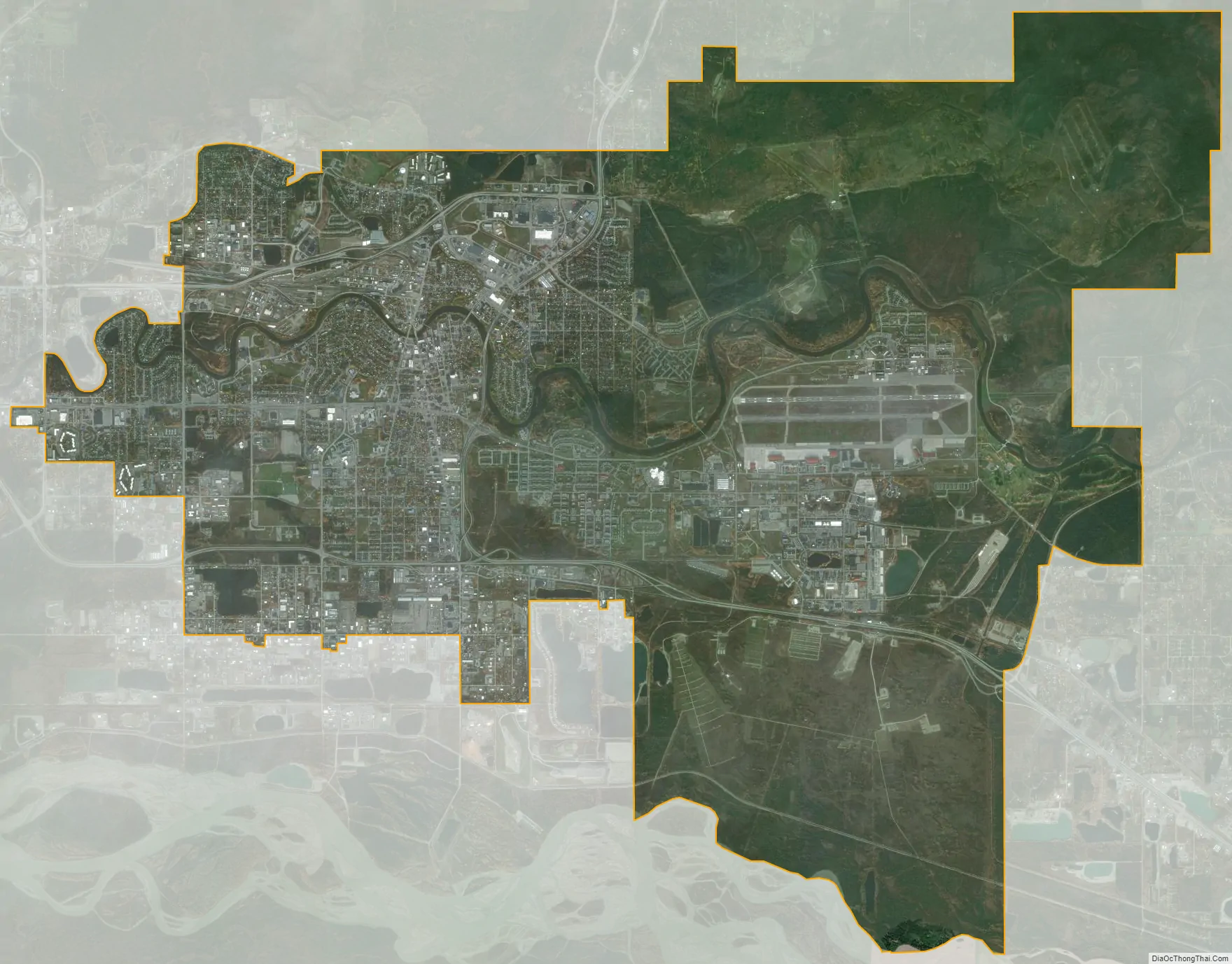

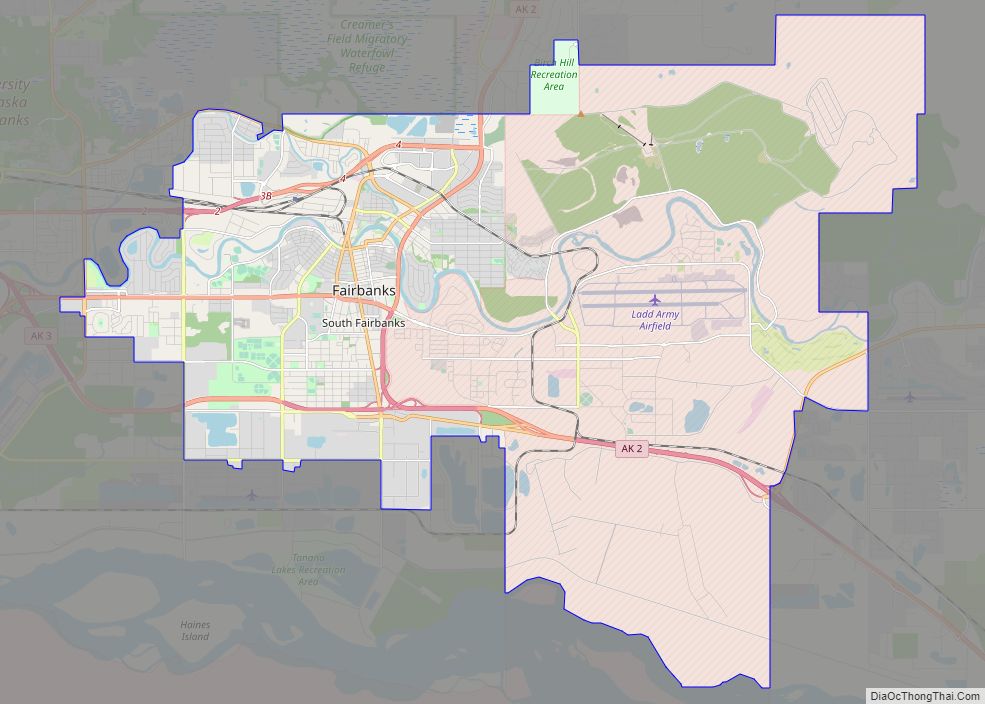

Fairbanks city Satellite Map

Geography

Topography

Fairbanks is in the central Tanana Valley, straddling the Chena River near its confluence with the Tanana River. Immediately north of the city is a chain of hills that rises gradually until it reaches the White Mountains and the Yukon River. The city’s southern border is the Tanana River. South of the river is the Tanana Flats, an area of marsh and bog that stretches for more than 100 miles (160 km) until it rises into the Alaska Range, which is visible from Fairbanks on clear days. To the east and west are low valleys separated by ridges of hills up to 3,000 feet (910 m) above sea level.

The Tanana Valley is crossed by many low streams and rivers that flow into the Tanana River. In Fairbanks, the Chena River flows southwest until it empties into the Tanana. Noyes Slough, which heads and foots off the Chena River, creates Garden Island, a district connected to the rest of Fairbanks by bridges and culverted roads.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 32.7 square miles (85 km); 31.9 square miles (83 km) of it is land and 0.8 square miles (2.1 km) of it (2.48%) is water.

Location

The city is extremely far north, close to 16 degrees north of the Pacific border between the U.S. and Canada. It is on roughly the same parallel as the northern Swedish city of Skellefteå and Finnish city of Oulu. Due to its warm summers, however, Fairbanks is south of the arctic tree line. Because of this, the white night phenomenon occurs here on the summer solstice.

Climate

Fairbanks’s climate is classified as humid continental (Köppen Dfb) closely bordering on a subarctic climate (Dfc), with long very cold winters and short warm summers. October through February are the snowiest months, and there is usually additional snow from March to May. On average, the season’s first accumulating snowfall and first inch of snow fall on October 1 and October 11, respectively; the average last inch and last accumulating snowfall are respectively on March 29 and April 15, though there can be snow flurries in May. The snowpack is established by October 18, on average, and remains until April 23. Snow occasionally arrives early and in large amounts. On September 13, 1992, 8 inches (20 cm) of snow fell in the city, bending trees still laden with fall leaves. That September was also one of the snowiest on record, as 24 inches (61 cm) fell, compared to the 1991-2020 median of only a trace during the month. November and December are the snowiest months, whilst in contrast, March and April are not very snowy, as these are typically very dry months in central Alaska. The snowiest season has been from July 1990 to June 1991 with 147.3 inches (3.74 m), whilst the least snowy was from July 1918 to June 1919 with only 12.0 inches (0.30 m).

The average first and last dates with a freezing temperature are September 11 and May 14, respectively, allowing a growing season of 119 days, although freezes have occurred in June, July, and August; the last light frost is often in early June; and the first light fall frost is often in late August or early September. The plant hardiness zone is 2 with annual mean minimums below -40.

Fairbanks is the coldest large city in the U.S.; normal monthly mean temperatures range from −8.3 °F (−22.4 °C) in January to 62.9 °F (17.2 °C) in July. On average, temperatures reach −40 °F (−40 °C) and 80 °F (27 °C) on 7.0 and 13 days annually, respectively, and the last winter that failed to reach the former mark was that of 2017-18. Between 1995 and 2008, inclusive, Fairbanks failed to record a temperature of 90 °F or 32 °C. The highest recorded temperature in Fairbanks was 99 °F (37 °C) on July 28, 1919, compared to the Alaska-wide record high temperature of 100 °F (38 °C), recorded in Fort Yukon. The lowest was −66 °F (−54 °C) on January 14, 1934. The warmest calendar year in Fairbanks was 2019, when the average annual temperature was 32.5 °F (0.3 °C), while the coldest was 1956 with an annual mean temperature of 21.3 °F (−5.9 °C). The warmest month has been July 1975 with a monthly mean of 68.4 °F (20.2 °C) and the coldest January 1906 which averaged −36.4 °F (−38.0 °C). Low temperatures below 0 °F or −18 °C have been recorded in every month outside June through September. The record cold daily maximum is −58 °F (−50 °C) on January 18, 1906, and the record warm daily minimum is 76 °F (24 °C) on June 26, 1915; the only other occurrence of a 70 °F (21 °C) daily minimum was June 25, 2013 in the midst of a particularly warm summer.

These widely varying temperature extremes are due to three main factors: temperature inversions, daylight, and wind direction. In winter, Fairbanks’ low-lying location at the bottom of the Tanana Valley causes cold air to accumulate in and around the city. Warmer air rises to the tops of the hills north of Fairbanks, while the city itself experiences one of the biggest temperature inversions on Earth. Heating through sunlight is limited because of Fairbanks’s high-latitude location. At the winter solstice, the center of the sun’s disk is less than two degrees over the horizon (1.7 degrees) at the local noon (not the time zone noon). Fairbanks experiences 3 hours and 41 minutes of sunlight on December 21 and 22. At the summer solstice, about 182 days later, on June 20 and 21, Fairbanks receives 21 hours and 49 minutes of sunlight. After sunset, twilight is bright enough to allow daytime activities without any electric lights, since the center of the sun’s disk is just 1.7 degrees below horizon. During winter, the direction of the wind also causes large temperature swings in Fairbanks. When the wind blows from any direction but the south, average weather ensues. Wind from the south can carry warm, moist air from the Gulf of Alaska, greatly warming temperatures. When coupled with a chinook wind, temperatures well above freezing often result: for example, in the record warm January 1981, Fairbanks’ average maximum was 28.7 °F (−1.8 °C) and 15 days had a maximum above freezing, whilst during a spell of sustained chinook winds from December 4 to 8, 1934 the temperature topped 50 °F or 10 °C for five consecutive days.

In addition to the chinook wind, Fairbanks experiences a handful of other unusual meteorological conditions. In summer, dense wildfire smoke accumulates in the Tanana Valley, affecting the weather and causing health concerns. When temperature inversions arise in winter, heavy ice fog often results. Ice fog occurs when air is too cold to absorb additional moisture, such as that released by automobile engines or human breath. Instead of dissipating, the water freezes into microscopic crystals that are suspended in the air, forming fog. Another one of Fairbanks’ unusual occurrences is the prevalence of the aurora borealis, commonly called the northern lights, which are visible on average more than 200 days per year in the vicinity of Fairbanks. The northern lights are not visible in the summer months due to the 24 hour daylight of the midnight sun. Fairbanks also has extremely low seasonal lag; the year’s warmest month is July, which averages only 1.9 °F (1.1 °C) warmer than June. Average daily temperatures begin to fall by late July and more markedly in August, which on average is 4.0 °F (2.2 °C) cooler than June.

From 1949 to 2018, Fairbanks’s mean annual temperature has risen by 3.9 °F (2.2 °C), a change comparable to the Alaska-wide average; winter was the season with the highest increase, at 8.1 °F (4.5 °C), while autumn had the smallest, at only 1.5 °F (0.83 °C). However, the mean annual temperature increase from 1976 to 2018 in Fairbanks stood at a more moderate 0.7 °F (0.39 °C); this stepwise temperature change, also observed elsewhere in Alaska, is explained by the Pacific Decadal Oscillation shifting from a negative phase to a positive phase from 1976 onward.

See or edit raw graph data.

See also

Map of Alaska State and its subdivision:- Aleutians East

- Aleutians West

- Anchorage

- Bethel

- Bristol Bay

- Denali

- Dillingham

- Fairbanks North Star

- Haines

- Juneau

- Kenai Peninsula

- Ketchikan Gateway

- Kodiak Island

- Lake and Peninsula

- Matanuska-Susitna

- Nome

- North Slope

- Northwest Arctic

- Prince of Wales-Outer Ketchi

- Sitka

- Skagway-Yakutat-Angoon

- Southeast Fairbanks

- Valdez-Cordova

- Wade Hampton

- Wrangell-Petersburg

- Yukon-Koyukuk

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming