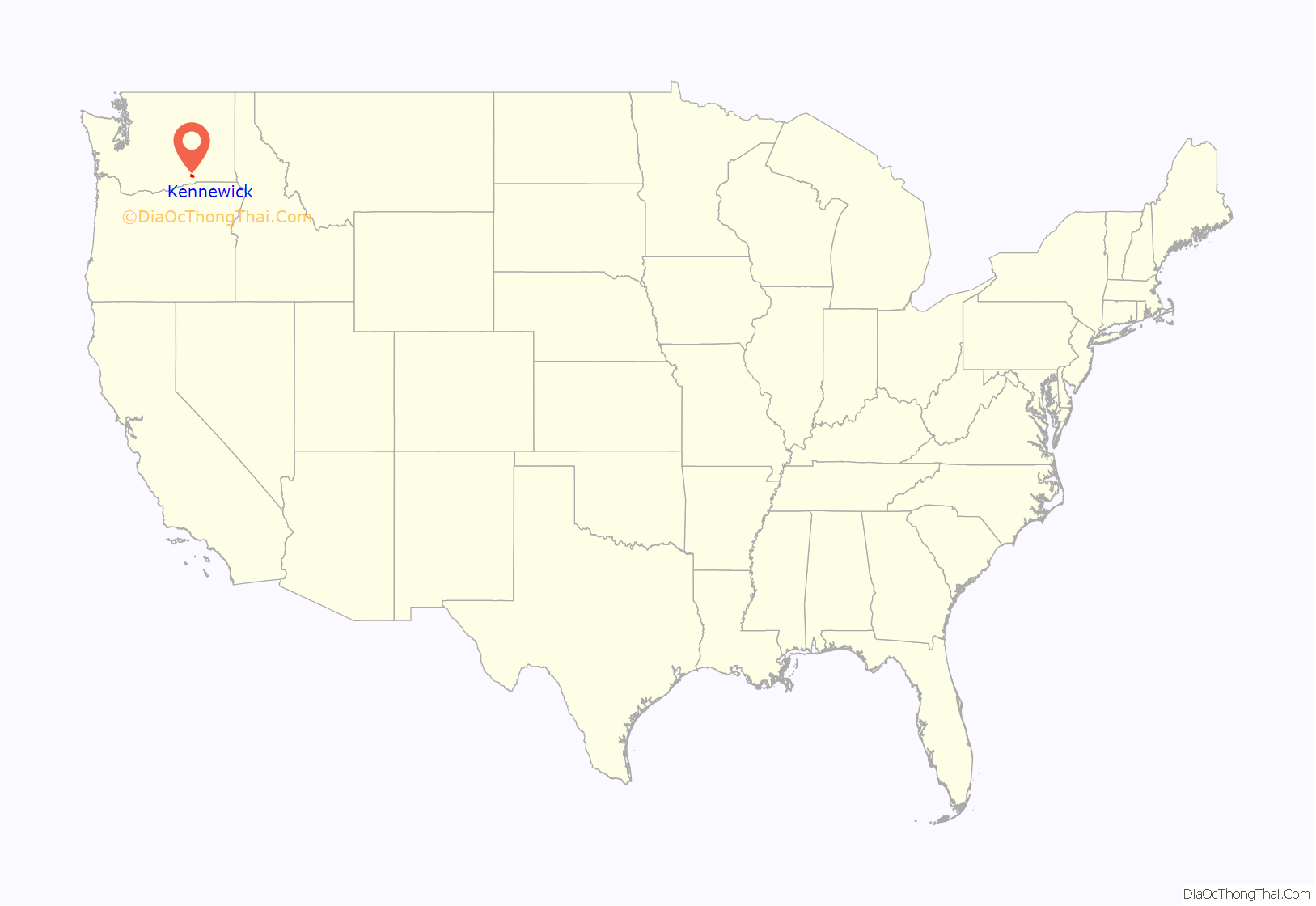

Kennewick (/ˈkɛnəwɪk/) is a city in Benton County in the U.S. state of Washington. It is located along the southwest bank of the Columbia River, just southeast of the confluence of the Columbia and Yakima rivers and across from the confluence of the Columbia and Snake rivers. It is the most populous of the three cities collectively referred to as the Tri-Cities (the others being Pasco and Richland). The population was 83,921 at the 2020 census.

The discovery of Kennewick Man along the banks of the Columbia River provides evidence of Native Americans’ settlement of the area for at least 9,000 years. American settlers began moving into the region in the late 19th century as transportation infrastructure was built to connect Kennewick to other settlements along the Columbia River. The construction of the Hanford Site at Richland accelerated the city’s growth in the 1940s as workers from around the country came to participate in the Manhattan Project. While Hanford and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory continue to be major sources of employment, the city’s economy has diversified over time and Kennewick today hosts offices for Amazon and Lamb Weston.

| Name: | Kennewick city |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 25 |

| LSAD Description: | city (suffix) |

| State: | Washington |

| County: | Benton County |

| Elevation: | 407 ft (124 m) |

| Land Area: | 27.45 sq mi (71.09 km²) |

| Water Area: | 1.39 sq mi (3.61 km²) |

| Population Density: | 3,072.86/sq mi (1,186.42/km²) |

| Area code: | 509 |

| FIPS code: | 5335275 |

| GNISfeature ID: | 1512347 |

| Website: | go2kennewick.com |

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

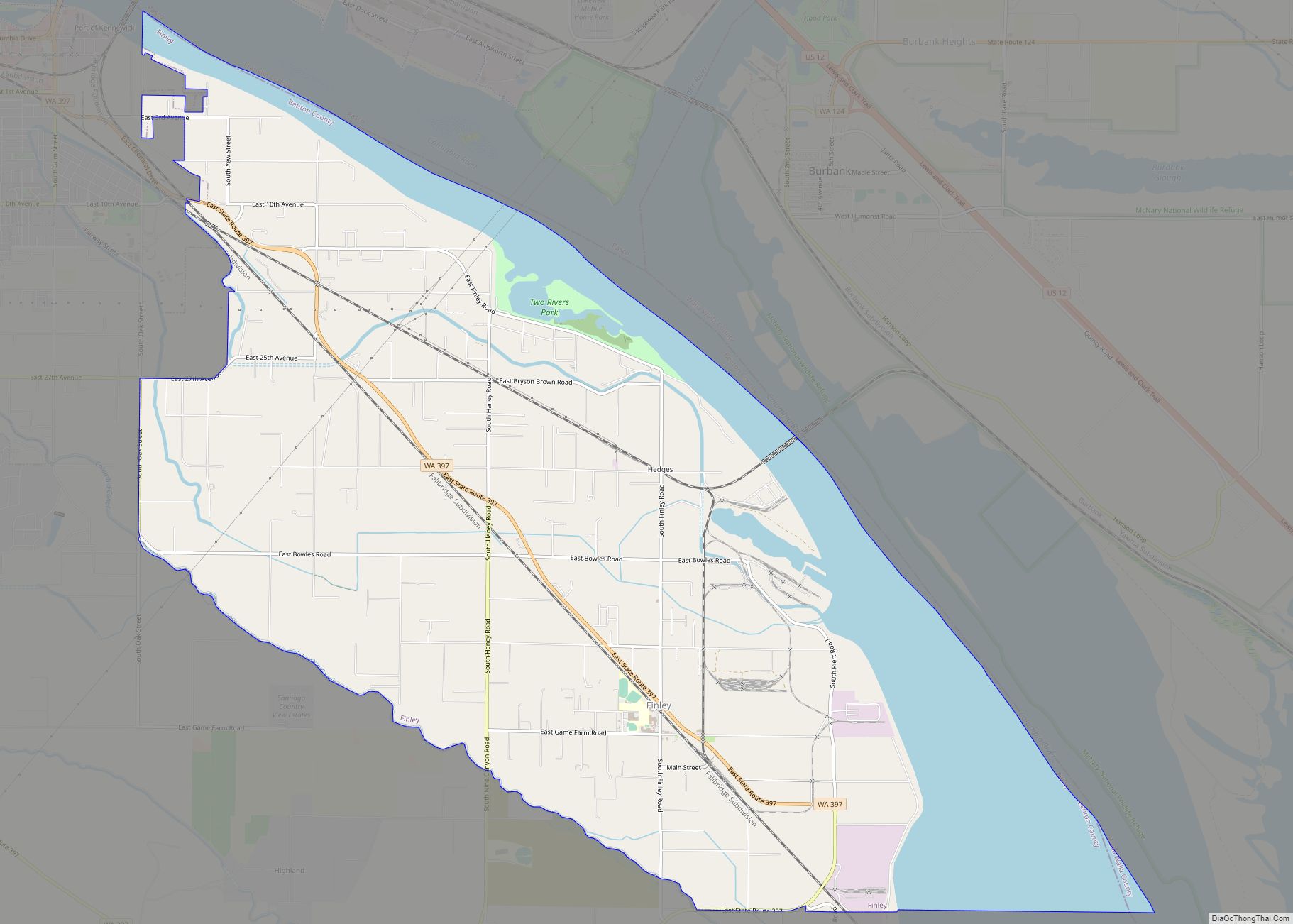

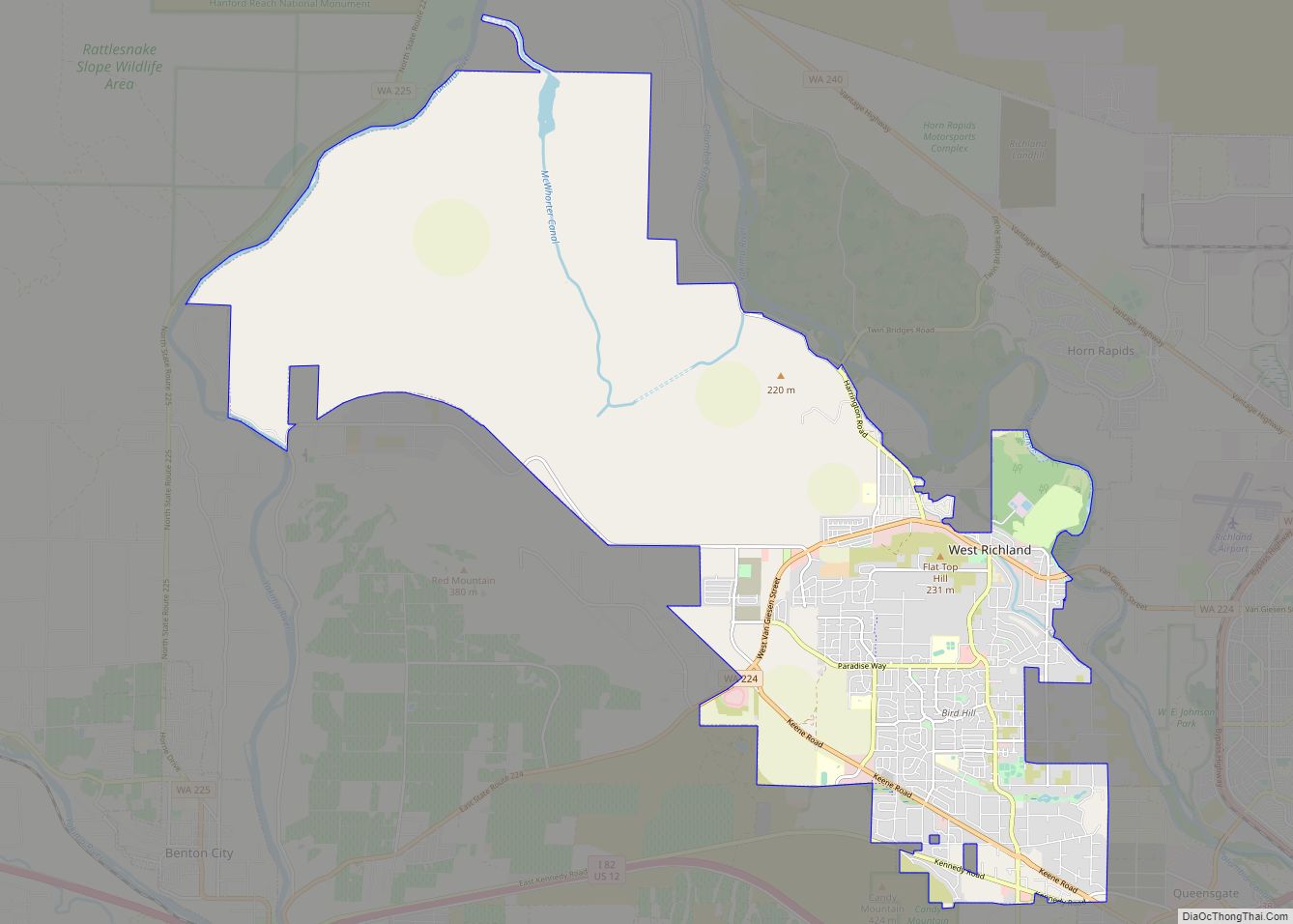

Kennewick location map. Where is Kennewick city?

History

Native peoples

Native Americans populated the area around modern-day Kennewick for millennia before being discovered and settled by European descendants. These inhabitants consisted of people from the Umatilla, Wanapum, Nez Perce, and Yakama tribes. Kennewick’s low elevation helped to moderate winter temperatures. On top of this, the riverside location made salmon and other river fish easily accessible. By the 19th century, people lived in and between two major camps in the area. These were located near present-day Sacajawea State Park in Pasco and Columbia Point in Richland. Lewis and Clark noted that there were many people living in the area when they passed through in 1805 and 1806. The map produced following their journey marks two significant villages in the area – Wollawollah and Selloatpallah. These had approximate populations of 2,600 and 3,000 respectively.

There are conflicting stories on how Kennewick gained its name, but these narratives attribute it to the Native Americans living in the area. Some reports claim that the name comes from a native word meaning “grassy place”. It has also been called “winter paradise,” mostly because of the mild winters in the area. In the past, Kennewick has also been known by other names. The area was known as Tehe from 1886 to 1891, and this name appears on early letters sent to the area with the city listed as Tehe, Washington. Other reports claim that the city’s name is derived from how locals pronounced the name Chenoythe, who was a member of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Settlement and early 20th century

The Umatilla and Yakama tribes ceded the land Kennewick sits on at the Walla Walla Council in 1855. Ranchers began working with cattle and horses in the area as early as the 1860s, but in general settlement was slow due to the arid climate. Ainsworth became the first non-Native settlement in the area—where U.S. Route 12 now crosses the Snake River between Pasco and Burbank. Some Ainsworth residents would commute to what is now Kennewick via small boats for work. All that remains of Ainsworth is a marker placed by the Washington State Department of Transportation near the site.

During the 1880s, steamboats and railroads connected what would become known as Kennewick to the other settlements along the Columbia River. Until the construction of a railroad bridge, rail freight from Minneapolis to Tacoma had to cross the Columbia River via ferry. In 1887, a temporary railroad bridge was constructed by the Northern Pacific Railroad connecting Kennewick and Pasco. That bridge could not endure the winter ice on the Columbia and was partially swept away in the first winter. A new, more permanent bridge was built in its place in 1888. It was around this time that a town plan was first laid out, centered around the needs of the railroad. A school was constructed using donated funds, but this burned soon after it was finished. This initial boom only lasted briefly, as most of the people who came to Kennewick left after the bridge was finished.

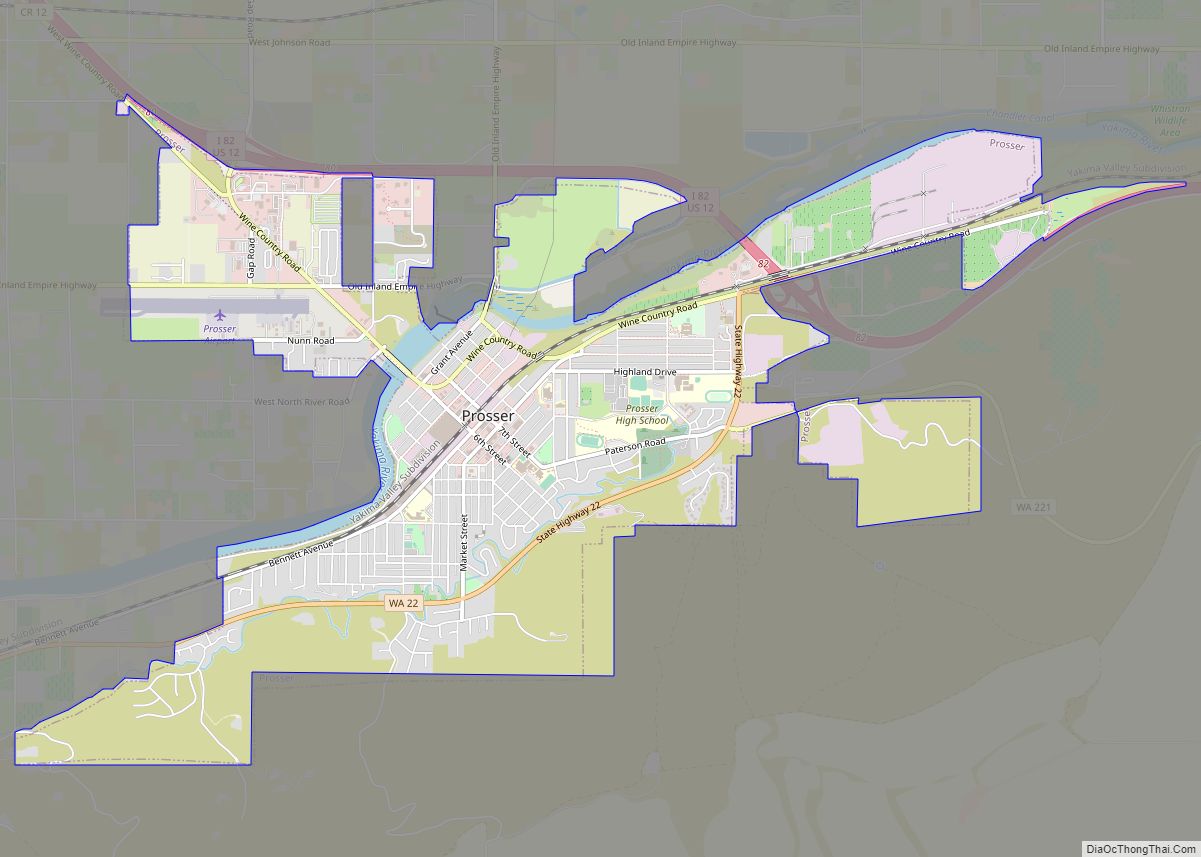

In the 1890s, the Northern Pacific Irrigation Company installed pumps and ditches to bring water for agriculture into the Kennewick Highlands. Once there was a reliable water source, orchards and vineyards were planted all over the Kennewick area. Strawberries were another successful crop. The turn of the century saw the creation of the city’s first newspaper, the Columbia Courier. Kennewick was officially incorporated on February 5, 1904. and the name of the newspaper changed to the Kennewick Courier in 1905 to reflect this change. In the following decade, an unsuccessful bid attempted to move the seat of Benton County from Prosser to Kennewick. There have been other unsuccessful attempts to make this move throughout the city’s history, most recently in 2010.

In 1915, the opening of the Celilo Canal connected Kennewick to the Pacific Ocean via the Columbia River. City residents hoped to capitalize on this new infrastructure by forming the Port of Kennewick, making the city an inland seaport. Freight and passenger ship traffic began that same year. The port also developed rail facilities in the area. Transportation in the region further improved with the construction of the Pasco-Kennewick Bridge in 1922, which is locally known as the Green Bridge. This bridge connected the two cities by vehicle traffic for the first time. Kennewick and Pasco both experienced decent growth and became informally known as the Twin Cities throughout the Columbia Basin because of their juxtaposition across the river from each other.

Like many other agricultural communities, the Great Depression had an impact in Kennewick. Despite lowered prices for crops grown in the region, the city continued to experience growth, gaining another 400 people during the 1930s. Growth was aided by federal projects that improved the Columbia River. Downstream, Bonneville Dam at Cascade Locks, Oregon allowed larger barges to reach Kennewick. Grand Coulee Dam, located upstream of Kennewick, fostered irrigation across the Columbia Basin north of Pasco, sending more raw material through Kennewick.

Hanford boom and racial discrimination

Kennewick and the greater Tri-Cities area experienced significant changes during World War II. In 1943, the United States opened the Hanford nuclear site in and north of Richland. Its purpose originally was to help produce nuclear weaponry, which the US was trying to develop. People came from across the United States to work at Hanford, who were unaware of what they were actually producing. They were only told that their work would help the war effort. The federal government constructed housing in Richland, but many employees of that site then commuted from Kennewick. The plutonium refined at the Hanford Site was used in the Fat Man bomb, which was dropped in Nagasaki in 1945 in the decisive final blow of the war. As the Hanford Site’s purpose has evolved, there has continually been a tremendous influence from the site on the workforce and economy of Kennewick. Due to activity at the Hanford Site, the 1950 census recorded major population growth in the Tri-Cities, with Richland overtaking to become the largest city in the region. From 1940 to 1950, the population of Richland grew from 247 residents to 21,793 residents, while Pasco gained from 3,913 to 10,114, and Kennewick increased from 1,918 to 10,085.

An effort to build a new bridge began in 1949 and was funded in 1951. Traffic between Kennewick and Pasco, largely due to commuters heading to and from the Hanford Site in Richland and McNary Dam, which was under construction near Umatilla, Oregon. The two-lane Green Bridge was the only one for automobiles across the Columbia River in the Tri-Cities at the time, and the 10,000 cars crossing it daily had created traffic problems. A new four-lane divided highway bridge, dubbed the Blue Bridge, opened in 1954 less than 2 miles (3.2 km) upstream from the Green Bridge. The Cable Bridge opened between Kennewick and Pasco in 1978 and was built to replace the Green Bridge. However, demolishing the Green Bridge proved to be controversial. Those seeking to preserve the bridge for historical reasons were able to stall the demolition, but it was eventually torn down in 1990.

Racial discrimination against African Americans was common in Kennewick before the civil rights movement. The city was a sundown town, requiring African Americans to be out of the city after nightfall. The only place they could live in the Tri-Cities at one time was east Pasco. Even during the day, African Americans would experience harassment by the general public and police, with some police officers stopping every person of color they found in the city after dark. In the 1940s, covenants restricted African Americans from owning property in the city. After the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Shelley v. Kraemer that racially restrictive covenants could not be enforced in state courts, these were replaced by informal agreements between homeowners and realtors to refuse to sell to African Americans.

Kennewick’s racial discrimination problems became a contributing factor behind a community college not being built there in the 1950s. In 1963, regional NAACP leaders started pressuring the state government to investigate exclusionary practices and staged demonstrations in front of city hall. Initial meetings led the state to determine that while no official policy banning African Americans from the city existed, racial discrimination was a significant barrier to that community living and feeling safe. Despite this, the Washington State Board Against Discrimination indicted Kennewick for its sundown town status.

1980 to present

The 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens caused a dusting of volcanic ash to fall on Kennewick. Higher accumulations were recorded in surrounding communities, such as Ritzville, where the ash plume was thick enough to trigger street lamps to turn on at noon. Kennewick and surrounding areas have been dusted by smaller eruptions of Mount St. Helens since.

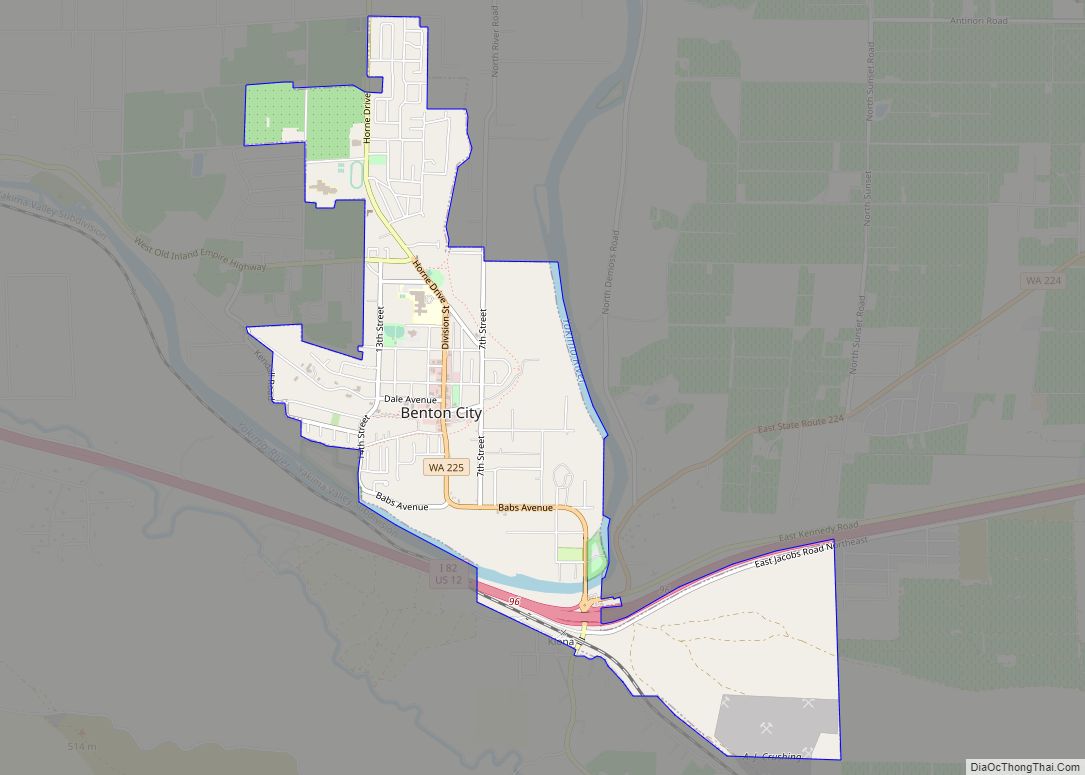

The area was connected to the Interstate Highway System in 1986 when construction on Interstate 82 (I-82) between Benton City and the south end of Kennewick was completed. This came after over a decade of fighting between Washington and Oregon regarding the planned route of the freeway. With backing from Tri-Cities and Walla Walla area businesses, Washington had pushed for a route that connected those cities. With Oregon eventually opposing proposed routes that didn’t cross the Umatilla Bridge, a compromise was reached placing I-82 on its current alignment to the south and southwest of Kennewick while authorizing the construction of Interstate 182 as a spur heading directly into Richland and Pasco.

The 1980s also brought the two most serious attempts to merge Kennewick with the other cities in the Tri-Cities, both of which failed. This resulted from an economic down turn in the area caused by the cancellation of two proposed nuclear power plants on the Hanford Site. The first proposal was to consolidate all three cities (Kennewick, Pasco, and Richland) into one, while the second only included Kennewick and Richland. Support for both of these attempts was strong in Richland, but voters in Kennewick and Pasco were not on board.

The Toyota Center was used as a venue for ice hockey and figure skating during the 1990 Goodwill Games. This international sporting competition was similar to the Olympic Games, but significantly smaller in scale. Most of the events were held in the host city, Seattle, but were also staged in other areas of the state, including Tacoma and Spokane.

In 1996, an ancient human skeleton was found on a bank of the Columbia River. Known as Kennewick Man, the remains are notable for their age (some 9,300 years). Ownership of the bones has been a matter of controversy with Native American tribes in the Inland Northwest claiming the bones to be from an ancestor of theirs and wanting them to be reburied. After a court litigation, a group of researchers were allowed to study the remains and perform various tests and analyses. They published their results in a book in 2014. A 2015 genetic analysis confirmed the ancient skeleton’s ancestry to the Native Americans of the area (some observers contended that the remains were of European origin). The genetic analysis has notably contributed to knowledge about the peopling of the Americas.

Kennewick fared better than most of the state during the Great Recession, primarily due to consistent job growth in the metro area during that time. This was largely driven by the Hanford Site, which only had one significant period of layoffs which briefly caused economic uncertainty. Home sales experienced a small decline from 2007 to 2009, but rebounded in 2010. Since the recession, Kennewick has expanded greatly. While growth has been experienced throughout the city, new development has been strongest in the Southridge area along U.S. Route 395 (US 395) and in the west part of the city thanks to their access to major roads and the ample land available in those areas when development started.

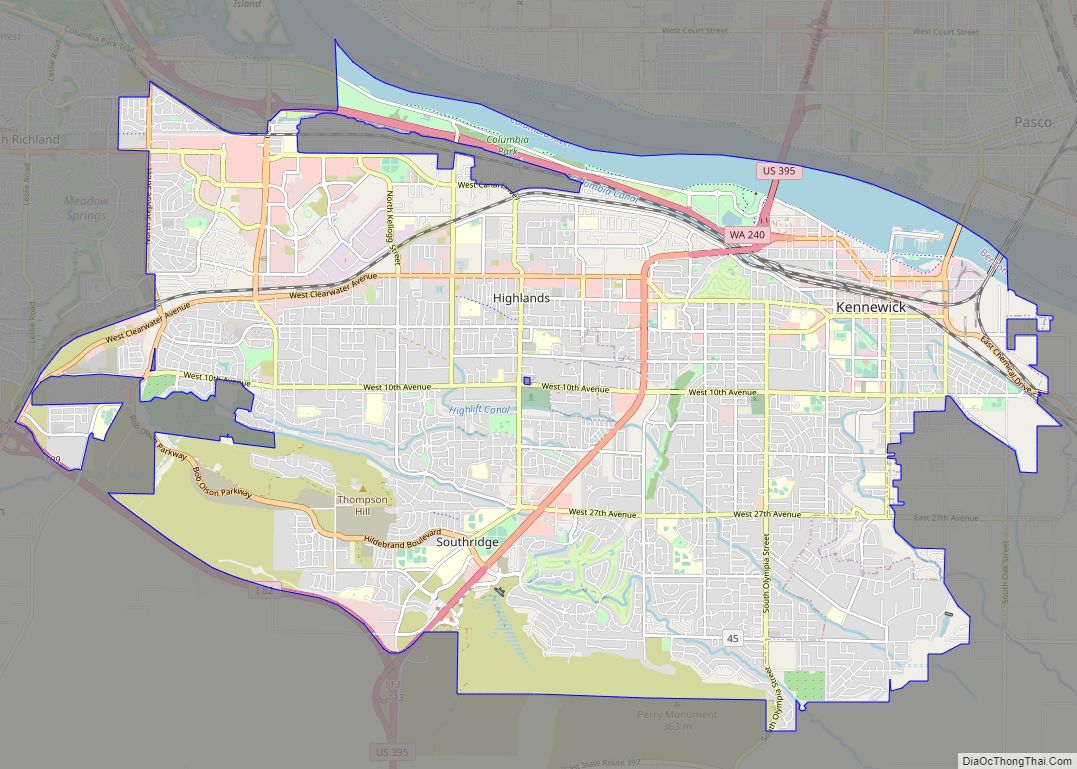

Kennewick Road Map

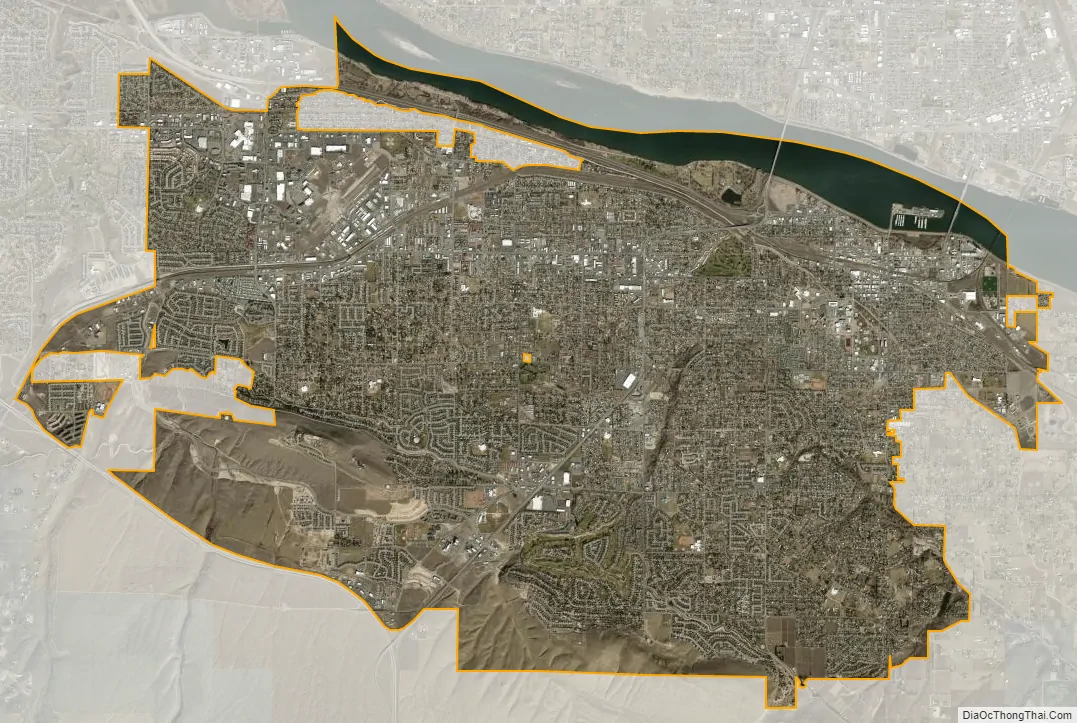

Kennewick city Satellite Map

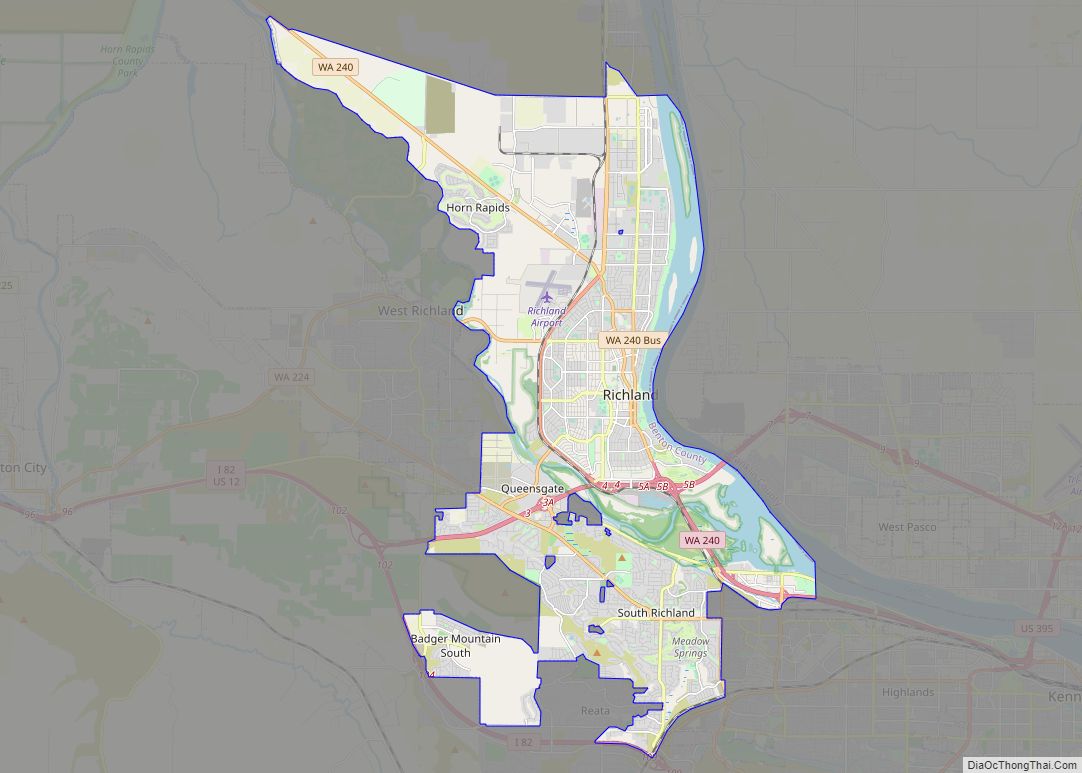

Geography

Kennewick is located in Eastern Washington along the south side of the Columbia River and is one of three cities in the Tri-Cities. The other two cities are Richland, which is upstream of Kennewick on the same side of the river, and Pasco, which is across the river. The elevation within the city rises from the river to a line of ridges on the south side of town that are a result of the same anticline that created Badger Mountain and Rattlesnake Mountain. Beyond that line of ridges, the city slopes up toward the Horse Heaven Hills. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 28.36 square miles (73.45 km), of which, 26.93 square miles (69.75 km) is land and 1.43 square miles (3.70 km) is water. The former community of Vista is now a neighborhood fully contained within Kennewick.

The city overlies basalt laid down by the Columbia River Basalt Group, which was a type of volcanic eruption known as a flood basalt. This erupted from fissures that were geographically spread throughout eastern Washington, eastern Oregon, and far western Idaho. Most of the lava erupted between 17 and 14 million years ago, with smaller eruptions lasting as late as 6 million years ago. The nearest eruptive vent to Kennewick from this period is near Ice Harbor Dam along the Snake River upstream of Burbank and Pasco. While outcroppings from the basalt flows can be seen throughout Kennewick, they are mostly buried by sediments.

The first major sediment deposit following the eruptions is the Ringold Formation, which was placed by the Columbia River between 8 and 3 million years ago. Further deposition came as a result of the Missoula Floods. At the end of the last glacial maximum, an ice dam blocked the Clark Fork River in Montana. The pressure from the resulting lake would periodically build to the point that the dam would fail, sending massive amounts of water cascading to the Pacific Ocean. The flood’s movement was impeded by the Horse Heaven Hills, creating a temporary lake known as Lake Lewis. This abrupt halt in flow allowed the floodwater to drop a significant amount of sediment before passing through Wallula Gap toward Hermiston. During the largest floods, the water’s surface reached 1,250 feet (380 m) above sea level. This completely covered all of the land within Kennewick’s city limits.

Earthquakes are a hazard in Kennewick, though not to the same extent or frequency as areas west of the Cascade Range like the Puget Sound Region. The entire Pacific Northwest is threatened with subduction zone earthquakes that can exceed magnitudes of 9 on the moment magnitude scale. The last of these earthquakes, which could be compared to the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake in Japan, occurred in 1700. Should the next earthquake occur, damage is expected to be minimal in and around Kennewick, but destruction west of the Cascades could have a major impact of the economy of inland areas. These subduction zone earthquakes will be centered on the boundary between the North American Plate and the Juan de Fuca Plate, which is located offshore. Fault lines closer to Kennewick also produce earthquakes. While these are weaker, they can still cause damage. One such earthquake, named the 1936 State Line earthquake, occurred near Walla Walla with damage extending as far away as Prosser.

Climate

Kennewick has a semi-arid climate (Köppen BSk), that closely borders on a desert climate (Köppen BWk) due to its position east of the Cascade Mountains. The Cascades create an effective rain shadow, causing Kennewick to receive a fraction of the precipitation that cities west of the mountains like Portland and Seattle get annually, with values being more similar to that of Phoenix, Arizona. The mountains also insulate Kennewick from the moderating effects of the Pacific Ocean, allowing the city to experience more extreme temperatures.

Before McNary Dam was built on the Columbia River downstream of Kennewick, the river would periodically flood. The worst of these floods happened in 1948 and caused one death and $50 million ($533.6 million in 2019) worth of damage. The government responded by building the McNary Levee System to protect lower parts of town. Floods like this were the result of melting snow, and were most extreme when a heavy snowpack developed in the mountains over winter followed by a strong regional heatwave. The flood threat from the Columbia has significantly decreased since dams were built. Zintel Canyon Dam located near the Southridge Sports and Events Complex was built to protect parts of the city from a 100-year flood. While the creek that flows through Zintel Canyon typically runs dry, summer thunderstorms in the Horse Heaven Hills can generate destructive flash floods.

Laying at the bottom of a basin, temperature inversions can develop, creating dense fog and low clouds in Kennewick. This is particularly common in the winter and can last for several days. Inversions form during periods of high pressure. High pressure combining with the low angle of the sun in winter brings stability in the atmosphere, allowing denser cold air to sink to the floor of the Columbia Basin. Pollutants will also become trapped, lowering the air quality. When fog develops during an inversion, it will often limit diurnal temperature changes to just a few degrees. Temperatures in areas above the inversion will often be warmer despite being at a higher elevation. These inversions cause a major decrease in the amount of sunshine Kennewick receives annually. If a weather system drops precipitation but isn’t strong enough to clear the inversion, freezing rain or sleet can fall in Kennewick.

The average annual wind speed in Kennewick is 8 miles per hour (13 km/h), but strong winds are a common occurrence in Kennewick and can sometimes cause damage. Wind and the arid nature of the region can cause dust storms. These events can happen any time of the year but is most common in the spring and fall months when farms in the region have high amounts of exposed soil. Chinook winds can also be experienced during the winter. These are formed when moisture gets removed from air moving across the Cascade Mountains, allowing the air to warm significantly as it descends into the Yakima Valley and Columbia Basin. Many of the high temperature records set during the winter months result from Chinook events.

Summer brings extreme heat and low humidity, which are ideal conditions for wildfires in undeveloped areas adjacent to town. One such fire in 2018 started along Interstate 82 south of Kennewick and burned 5,000 acres (2,000 ha), destroying five homes on the edge of Kennewick. While rare, severe thunderstorms can also cause damage in Kennewick. Severe storms can produce damaging wind, hail, lightning, and weak tornadoes. No tornadoes were recorded in Kennewick between 1962 and 2011, but one did touch down in 2016.

See also

Map of Washington State and its subdivision:- Adams

- Asotin

- Benton

- Chelan

- Clallam

- Clark

- Columbia

- Cowlitz

- Douglas

- Ferry

- Franklin

- Garfield

- Grant

- Grays Harbor

- Island

- Jefferson

- King

- Kitsap

- Kittitas

- Klickitat

- Lewis

- Lincoln

- Mason

- Okanogan

- Pacific

- Pend Oreille

- Pierce

- San Juan

- Skagit

- Skamania

- Snohomish

- Spokane

- Stevens

- Thurston

- Wahkiakum

- Walla Walla

- Whatcom

- Whitman

- Yakima

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming