Fort Shaw (originally named Camp Reynolds) was a United States Army fort located on the Sun River 24 miles west of Great Falls, Montana, in the United States. It was founded on June 30, 1867, and abandoned by the Army in July 1891. It later served as a school for Native American children from 1892 to 1910. Portions of the fort survive today as a small museum. The fort lent its name to the community of Fort Shaw, Montana, which grew up around it.

Fort Shaw is part of the Fort Shaw Historic District and Cemetery, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places on January 11, 1985.

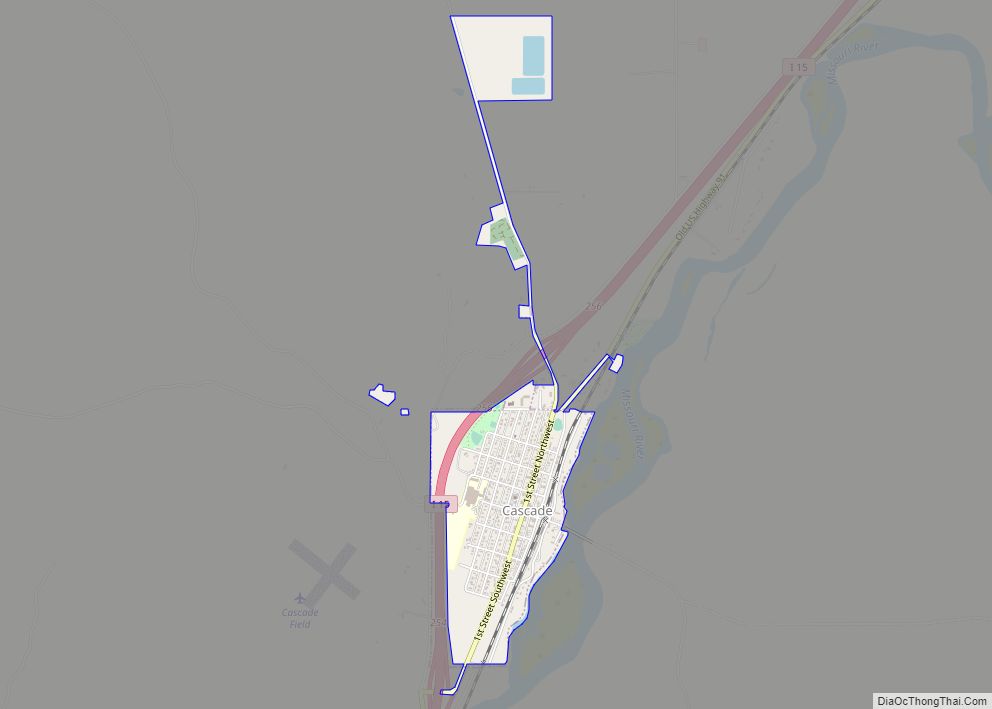

| Name: | Fort Shaw CDP |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 57 |

| LSAD Description: | CDP (suffix) |

| State: | Montana |

| County: | Cascade County |

| FIPS code: | 3028600 |

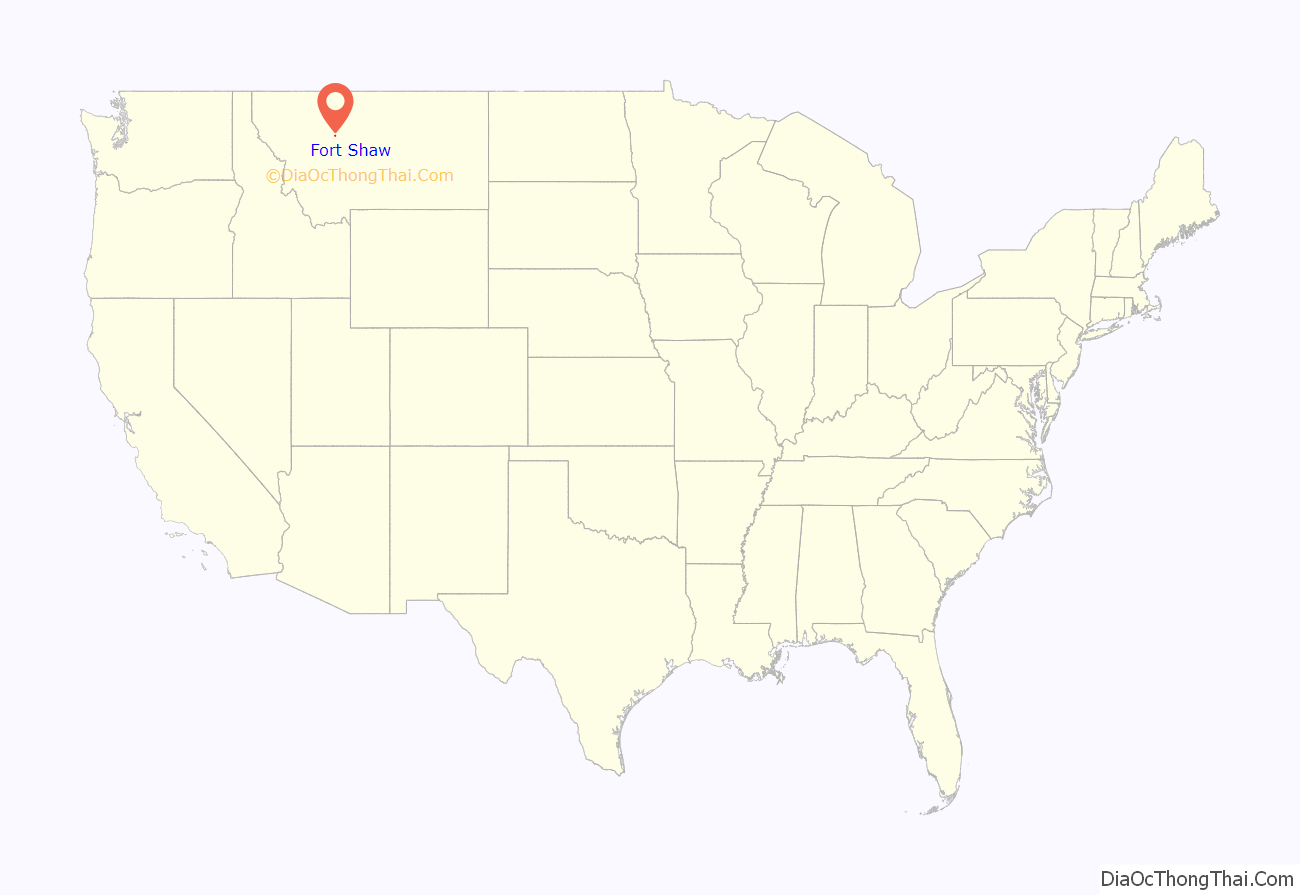

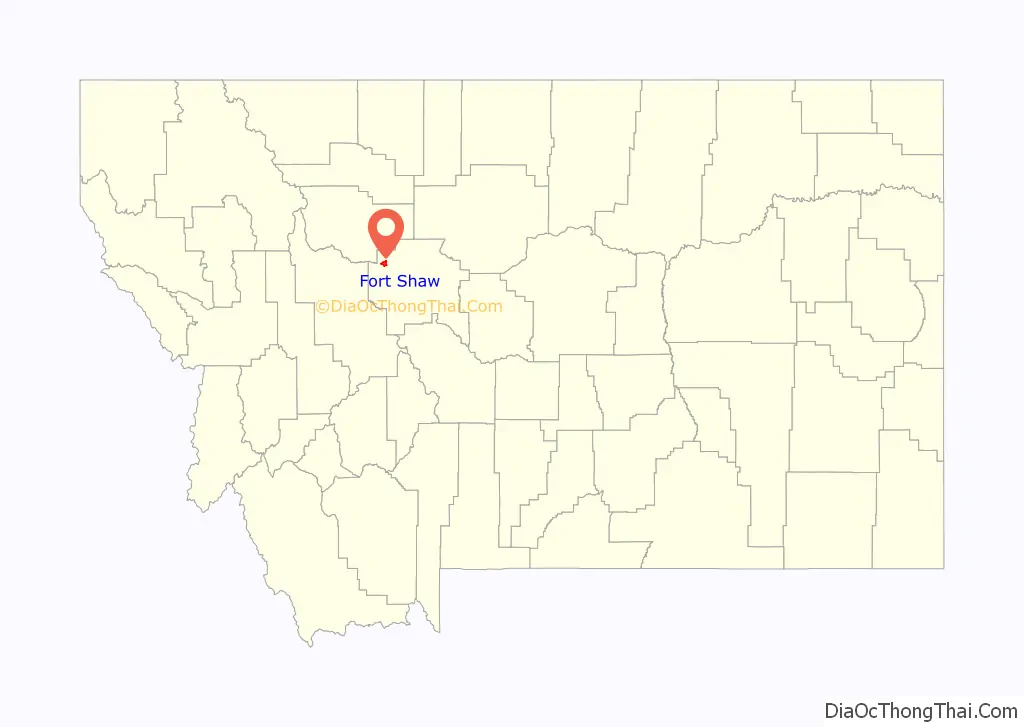

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

Fort Shaw location map. Where is Fort Shaw CDP?

History

Early leadership

Major William Clinton’s command of Fort Shaw was only temporary. On August 11, 1867, Colonel I. V. D. Reeves transferred the 13th Infantry Regiment’s headquarters to Fort Shaw. Lieutenant Colonel G. L. Andrews was regimental second-in-command, and named headquarters commandant, overseeing the operations of the fort itself. During their tenure at the fort, a steam engine was brought in to pump water from the river to the kitchens and sinks. The unit also received breech-loading rifles, which greatly increased its effectiveness. About 33 civilians were employed at the fort as well, working as blacksmiths, carpenters, clerks, masons, and saddlers. One of Colonel Reeves’ first actions was to disarm the Montana Militia, a short-lived paramilitary organization formed by Acting Governor Thomas Francis Meagher in 1864 and supplied with arms by the U.S. Army. Reeves acted quickly, and the militia was disbanded by October 1, 1867.

General Phillipe Régis de Trobriand took command of Fort Shaw on June 4, 1869. A steam engine (whether a second one or a replacement is unclear) was brought to the fort in 1869. Excessive drinking and desertion by his troops were a constant problem. General Trobriand and the 13th Infantry Regiment left Fort Shaw on June 11, 1870. His unit was replaced by the headquarters company and six companies of the 7th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel John Gibbon.

Command of Colonel Gibbon and fighting in the Indian Wars

Gibbon worked to improve living conditions at Fort Shaw. He improved the roofing of the barracks buildings, had the exterior walls of all buildings plastered, expanded the storehouses, and expanded and improved the corrals and stables. Irrigation for the fort’s vegetable garden was completed, and companies assigned to maintain each plot. In 1871, he obtained a plow for tilling the garden. He also worked to expand the fort’s civilian workforce, adding carpenters, masons, and sawmill operators. Desertion and theft of fort supplies, both major problems, were also reduced.

Gibbon also worked to improve security in the area. He began surveying and constructing a road between Fort Shaw and Camp Baker (near present-day White Sulphur Springs) to provide better communications with that post and to better monitor the movements of Native American groups and bands. This so improved security in the area that Gibbon counseled against the construction of a blockhouse at Camp Baker because it would send a signal to whites that the area was still not free from Native American attack. Gibbon also used his troops to scout out the little-explored area of the Rocky Mountain Front. These explorations led to the rediscovery and accurate mapping of Lewis and Clark Pass.

The area around Fort Shaw was a hotbed of conflict between Native Americans and white settlers in the late 1860s. A series of Piegan Blackfeet and Sioux raids between 1865 and 1869 left several whites dead. In mid-1869, two innocent Piegan Blackfeet were killed in retaliation in broad daylight in the town of Fort Benton, Montana, about 55 miles (89 km) to the northeast of Fort Shaw. One of them was the brother of the Piegan leader Mountain Chief, who initiated a series of reprisals which killed about 25 white settlers. In response, General Philip Sheridan ordered Major Eugene Baker to take two companies of the 2d Cavalry Regiment from Fort Ellis and two companies of infantry from Fort Shaw and attack Mountain Chief’s band of Piegans. Baker attacked the Piegans on the morning of January 23, 1870. Unfortunately, he attacked the wrong band: The Piegans were led by Heavy Runner, a Piegan Blackfeet who had signed a peace agreement with the United States. When Heavy Runner rushed out of his camp with his peace treaty in hand, he was shot dead. In what became known as the Marias Massacre, more than 173 Piegean Blackfeet (including 53 women and children) were murdered.

Just five years later, in 1874, gold was discovered by the U.S. Army in the Black Hills of the Dakotas. A gold rush occurred in 1875 and 1876 in which thousands of white miners and settlers flooded the area in violation of several treaties guaranteeing that the Black Hills would belong to the Lakota people. Conflict between Native Americans and white settlers broke out. Responding to pleas from whites, President Ulysses S. Grant decided to clear the Black Hills of all native people. After an attack against a combined Sioux-Cheyenne village on the Powder River by General George Crook accomplished little in March 1876, General Sheridan decided on a three-pronged attack to occur in southwestern Montana in the summer of 1876. Colonel Gibbon was ordered to form a “Montana Column” from elements of at Fort Shaw and Fort Ellis, and to march south across the plains to ensure that no Native American tribes moved north or west of the Yellowstone River. After reaching the Yellowstone, he was to move downstream until he rendezvoused with a “Dakota Column”, under the command of General Alfred Terry. Gibbon left Fort Shaw on March 17, 1877, with five companies (about 200 men and 12 officers), and reached Fort Ellis on March 22. In April, Gibbon left Fort Ellis with both infantry and cavalry (totalling about 450 men and officers), heading for the Yellowstone. On June 20, Gibbon’s command rendezvoused with Terry at the mouth of the Rosebud River. General Terry ordered his subordinate, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, to proceed south along the Rosebud and then west to the Little Bighorn River. Custer was to follow the Little Bighorn River north to the Bighorn River, where he was to rendezvous with Gibbon and Terry—who were to proceed west along the Yellowstone to the Bighorn, and then south along the Bighorn to meet Custer. Subsequently, Gibbon’s Fort Shaw soldiers did not participate in the Battle of the Little Bighorn on June 25–26, during which most of Custer’s command was famously wiped out. Gibbon entered the valley of the Little Bighorn on June 27, where the Fort Shaw soldiers assisted in burying the dead.

Soldiers at Fort Shaw participated in another famous Indian battle in 1877. For many years, several bands of the Nez Perce people lived in the valley of the Wallowa River in northeast Oregon. But increasing white settlement in the area led to calls to have the Native Americans placed on a reservation. In May 1877, General Oliver O. Howard ordered all remaining Nez Perce onto a reservation with 30 days. Several young Native Americans killed some white settlers, leading to a reprisal by General Howard. Yet, in the Battle of White Bird Canyon on June 17, 1877, a force of about 80 Nez Perce warriors defeated a unit of 200 of Howard’s artillery, cavalry, and infantry. More than 800 Nez Perce men, women, and children tried to flee over Lolo Pass into Montana to seek help from other tribes, which deeply alarmed whites in the Montana Territory. A hundred Nez Perce held off 500 U.S. Army troops at the Battle of the Clearwater on July 11–12. Colonel Gibbon hastily assembled a force of about 200 artillery, cavalry, and infantry and proceeded up the Bitterroot River into the Big Hole Basin to stop them. On August 9, Gibbon attacked with his infantry and artillery at dawn. But the Nez Perce captured his howitzer and Nez Perce sharpshooters killed 30 of his men and officers. The Battle of the Big Hole continued until August 10, as the Nez Perce pinned Gibbon’s men down in a coulee. The band finally fled, 89 of their own (mostly women and children) dead. After a lengthy flight through Montana, the Nez Perce finally surrendered at the Battle of Bear Paw near Chinook, Montana, on October 5, 1877. Montana saw its last skirmishes with Native Americans in 1878.

Later commanders

In the summer of 1878, the 7th Infantry was moved to Saint Paul, Minnesota, and Fort Shaw became the headquarters of the 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment under the command of Colonel John R. Brooke. Brooke was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel on March 20, 1879, and assigned to the 13th Infantry Regiment (then in the Dakotas). But undisclosed personnel issues kept Brooke at Fort Shaw. He was joined by Colonel Luther Prentice Bradley. There were six companies in the 3rd Infantry. Company A was assigned to Fort Benton. Companies C, E, F, and G were assigned to Fort Shaw. Company K was assigned to Fort Logan (the former Camp Baker).

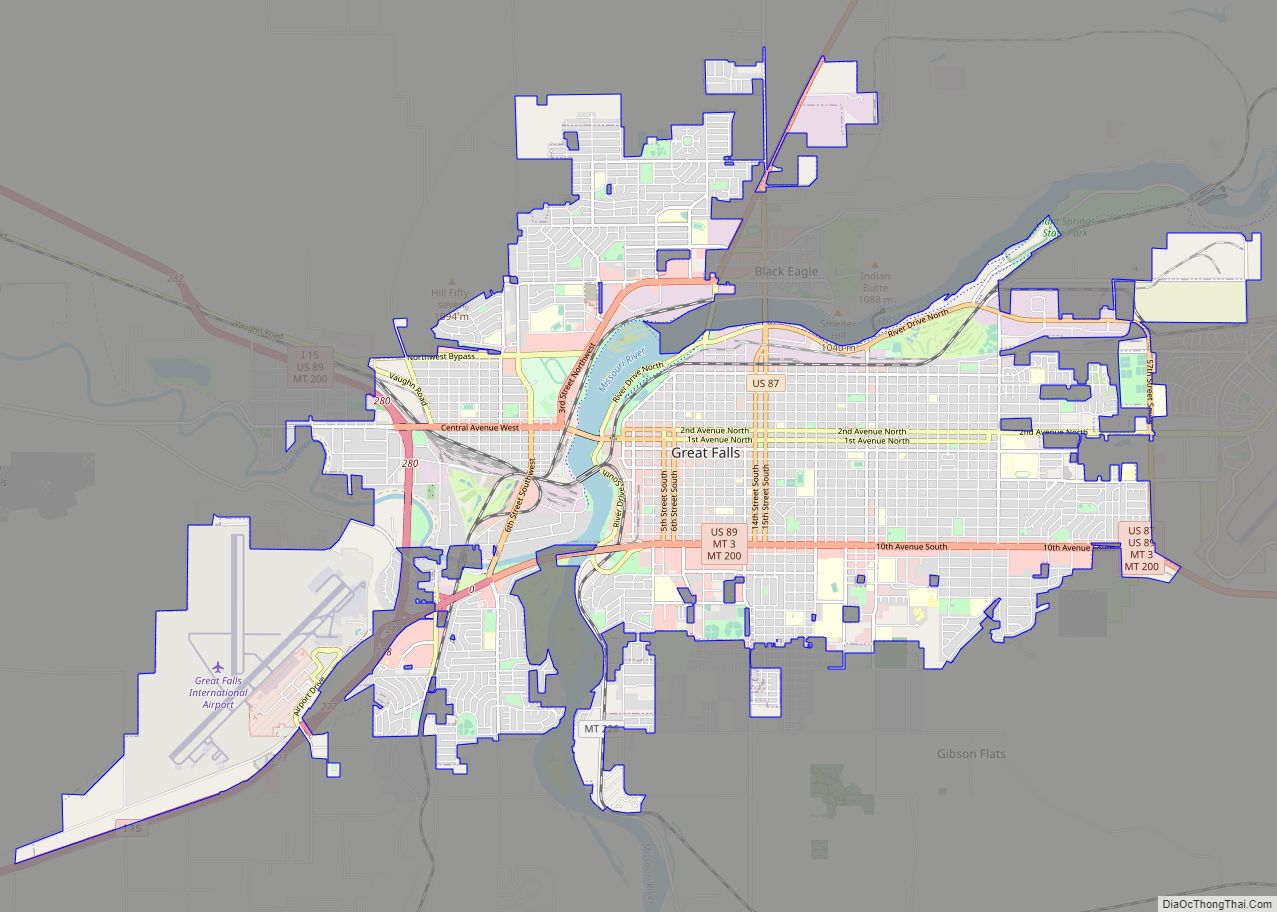

Life at Fort Shaw was increasingly peaceful. Company E of the 3rd Infantry was sent from Fort Shaw to Fort Ellis in the spring of 1879, and it was followed by Company C in the summer. (They stayed there until Fort Ellis closed in 1886, and then were transferred to Fort Custer, where they remained.) Companies A and K were reassigned to Fort Shaw in 1881. In the fall and summer of 1882 and 1883, at least two companies from Fort Shaw were kept in the field at all times, observing Native American movements and discouraging raids on white settlements south of the Piegan Blackfeet reservation. The peaceful life was not necessarily fun for the isolated soldiers, who often visited nearby communities to drink. In 1885, the first Independence Day celebrations occurred in Great Falls. Soldiers from Fort Shaw became roaring drunk during the day, and fired several cannonballs down Central Avenue (the city’s main street) around midnight.

In April 1888, Colonel Brooke was promoted to brigadier general, and the 3rd Infantry transferred to forts in the Dakotas and Minnesota. The 25th Infantry Regiment, under the command of Colonel George Lippitt Andrews, took up station at Fort Shaw in May 1888 in its stead. By this time, Fort Shaw was no longer seen as a key fort in the Army’s chain of military posts across Montana. Colonel Andrews, his headquarters company, and two companies of infantry resided at Fort Missoula, more than 200 miles (320 km) to the west over the Rocky Mountains. Just two companies of the 25th Infantry (I and K) resided at Fort Shaw, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel James J. Van Horn. These two companies were “skeletonized” in September 1890, leaving Fort Shaw with only a minimal military presence.

The construction of Fort Assinniboine (which cost $1 million to build) in 1879 led to the creation of a new center of U.S. military power in Montana far from the more settled central and southwestern parts of the state, and led to the eventual closure of Fort Shaw and Fort Ellis. Fort Shaw was abandoned by the U.S. Army on July 1, 1891.

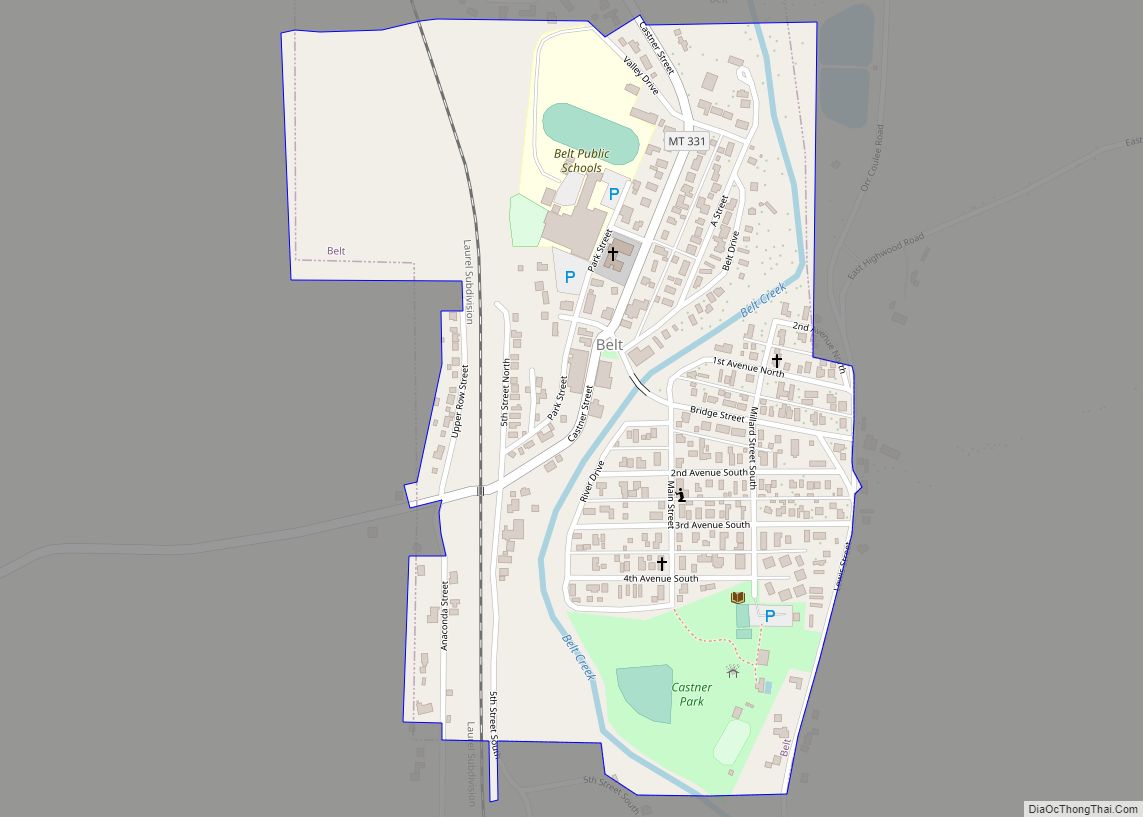

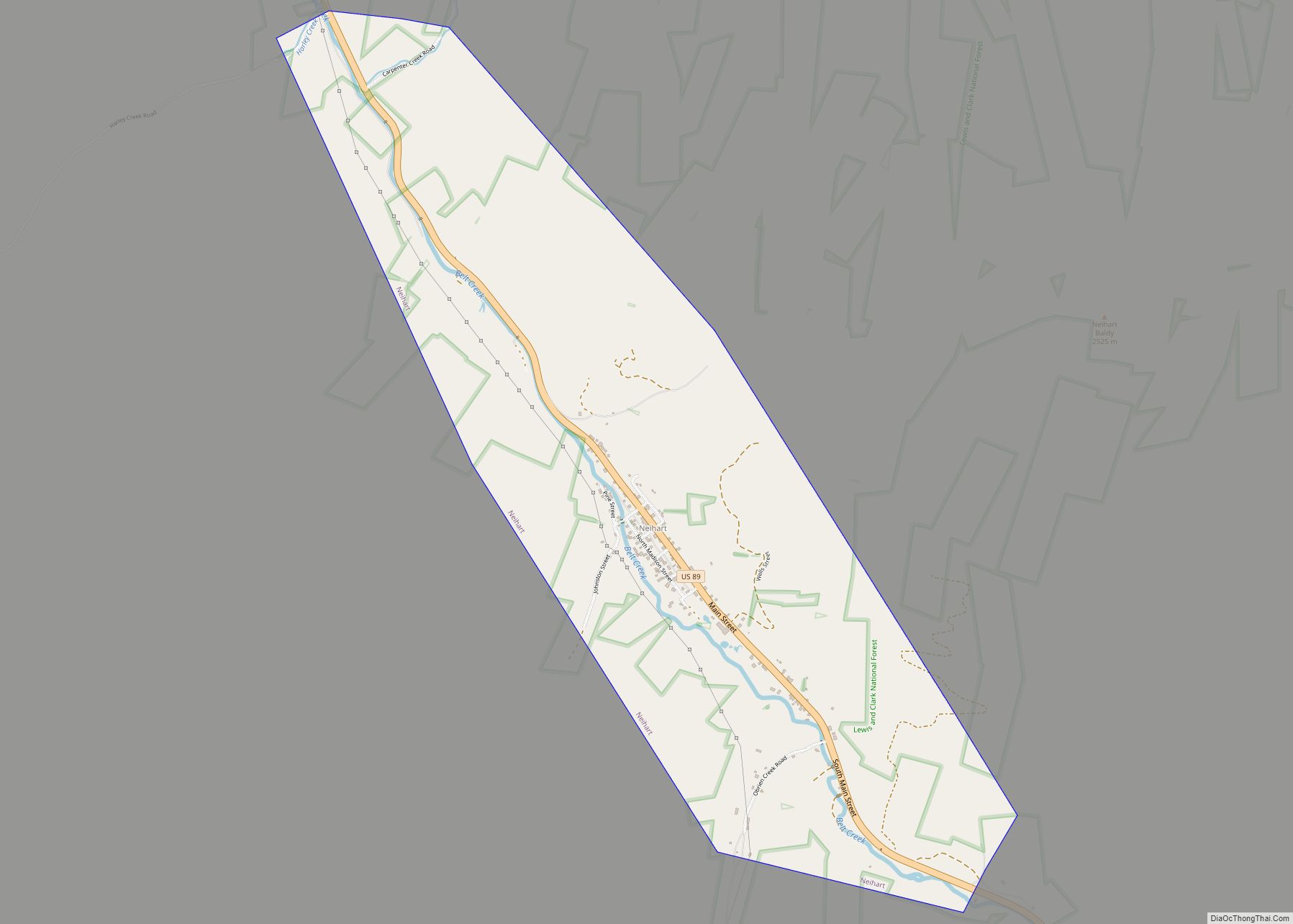

Fort Shaw Road Map

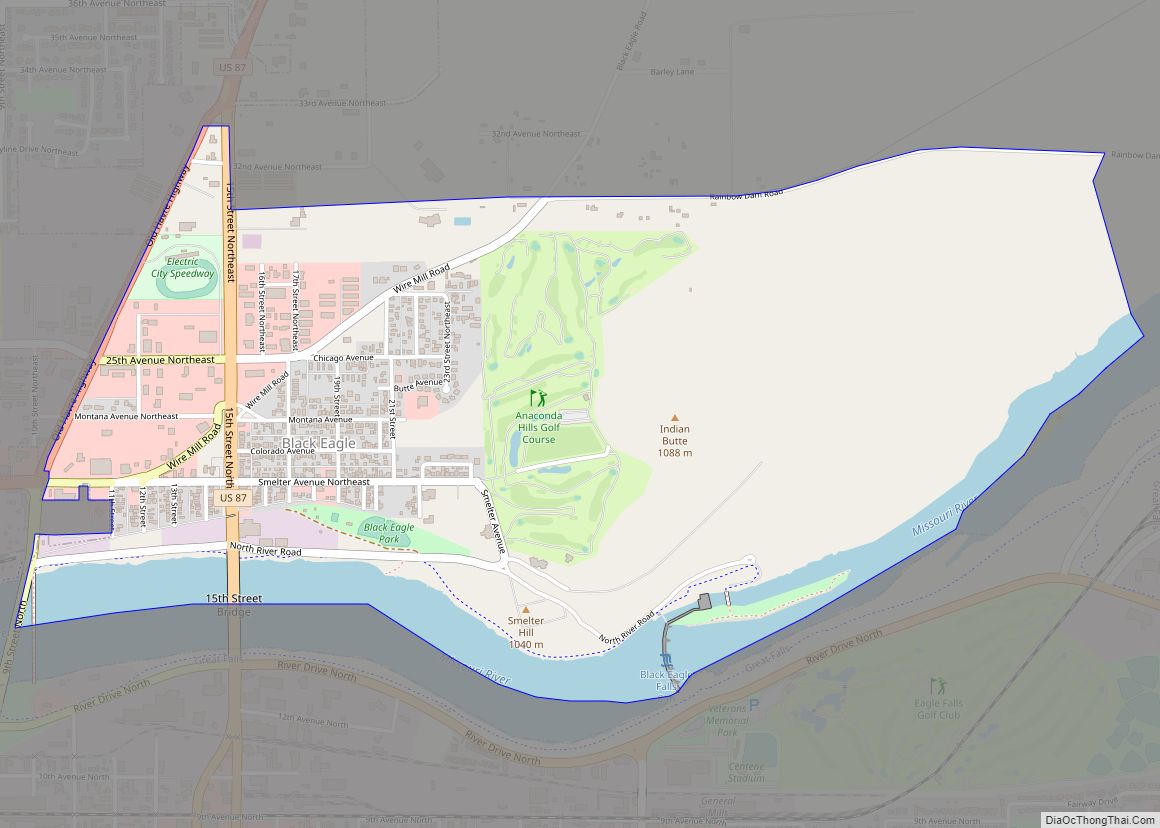

Fort Shaw city Satellite Map

See also

Map of Montana State and its subdivision:- Beaverhead

- Big Horn

- Blaine

- Broadwater

- Carbon

- Carter

- Cascade

- Chouteau

- Custer

- Daniels

- Dawson

- Deer Lodge

- Fallon

- Fergus

- Flathead

- Gallatin

- Garfield

- Glacier

- Golden Valley

- Granite

- Hill

- Jefferson

- Judith Basin

- Lake

- Lewis and Clark

- Liberty

- Lincoln

- Madison

- McCone

- Meagher

- Mineral

- Missoula

- Musselshell

- Park

- Petroleum

- Phillips

- Pondera

- Powder River

- Powell

- Prairie

- Ravalli

- Richland

- Roosevelt

- Rosebud

- Sanders

- Sheridan

- Silver Bow

- Stillwater

- Sweet Grass

- Teton

- Toole

- Treasure

- Valley

- Wheatland

- Wibaux

- Yellowstone

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming