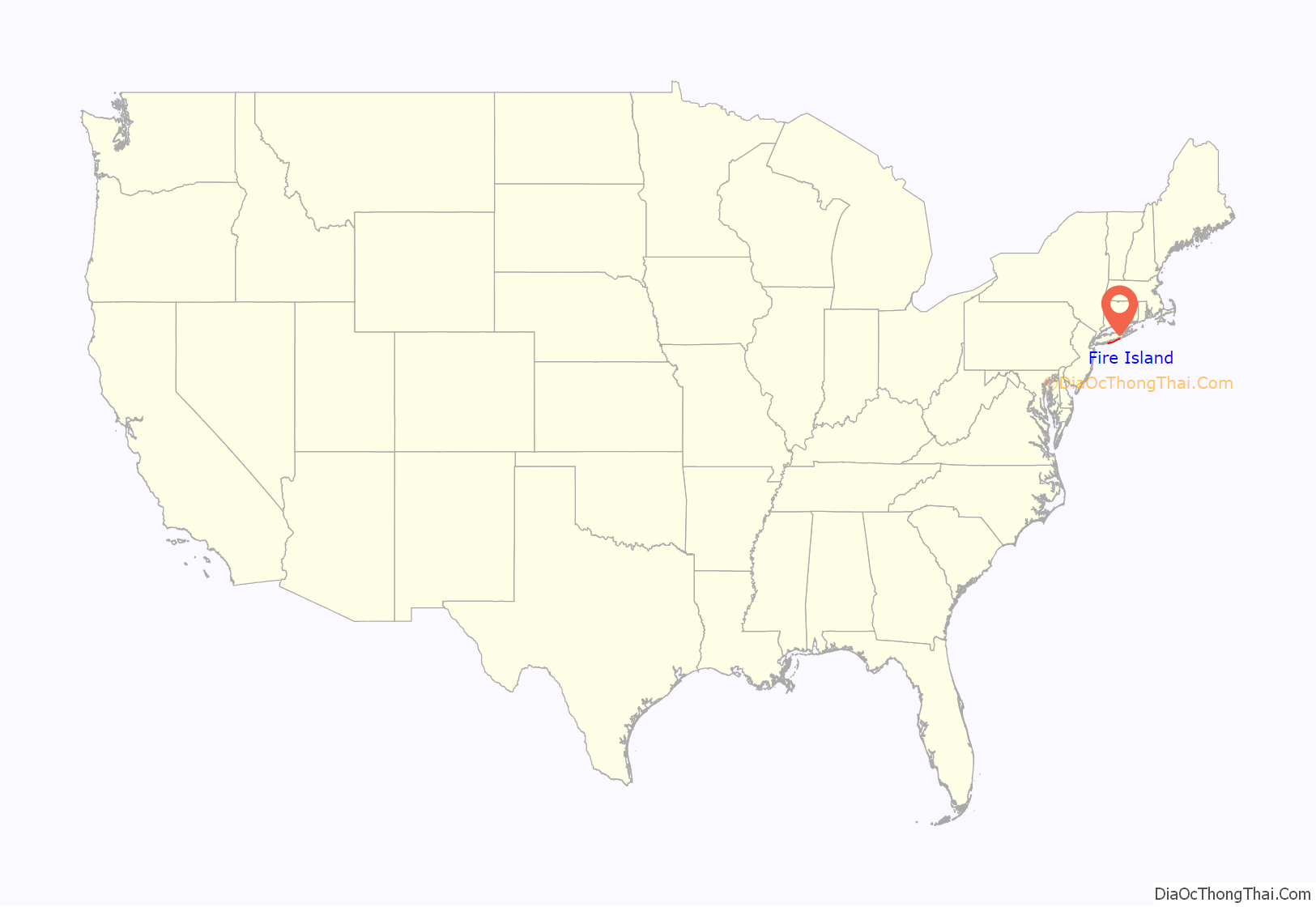

Fire Island is the large center island of the outer barrier islands parallel to the South Shore of Long Island, in the U.S. state of New York.

Occasionally, the name is used to refer collectively to not only the central island, but also Long Beach Barrier Island, Jones Beach Island, and Westhampton Island, since the straits that separate these islands are ephemeral. In 2012, Hurricane Sandy once again divided Fire Island into two islands. Together, these two islands are about 31 miles (50 km) long and vary between 520 and 1,310 feet (160 and 400 m) wide. The land area of Fire Island is 9.6 square miles (24.9 km).

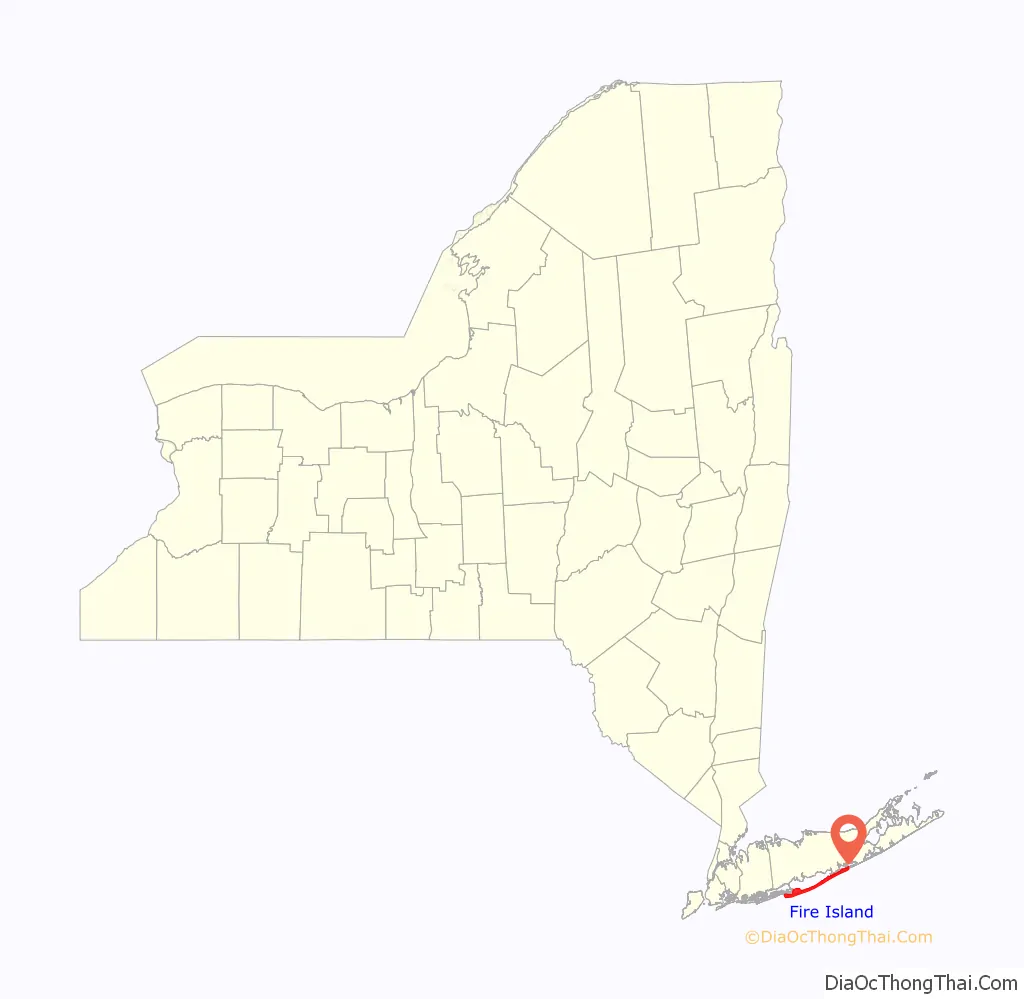

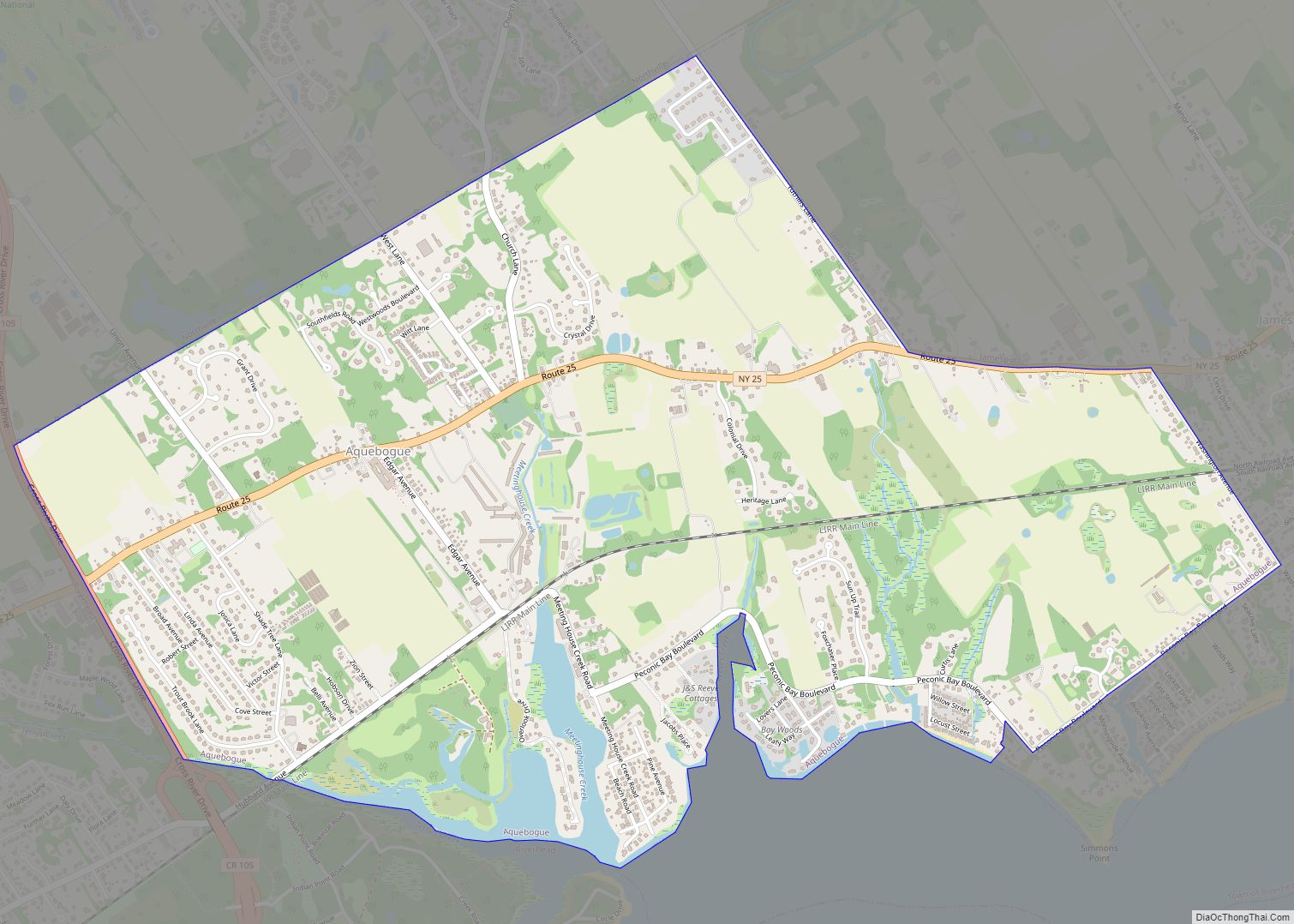

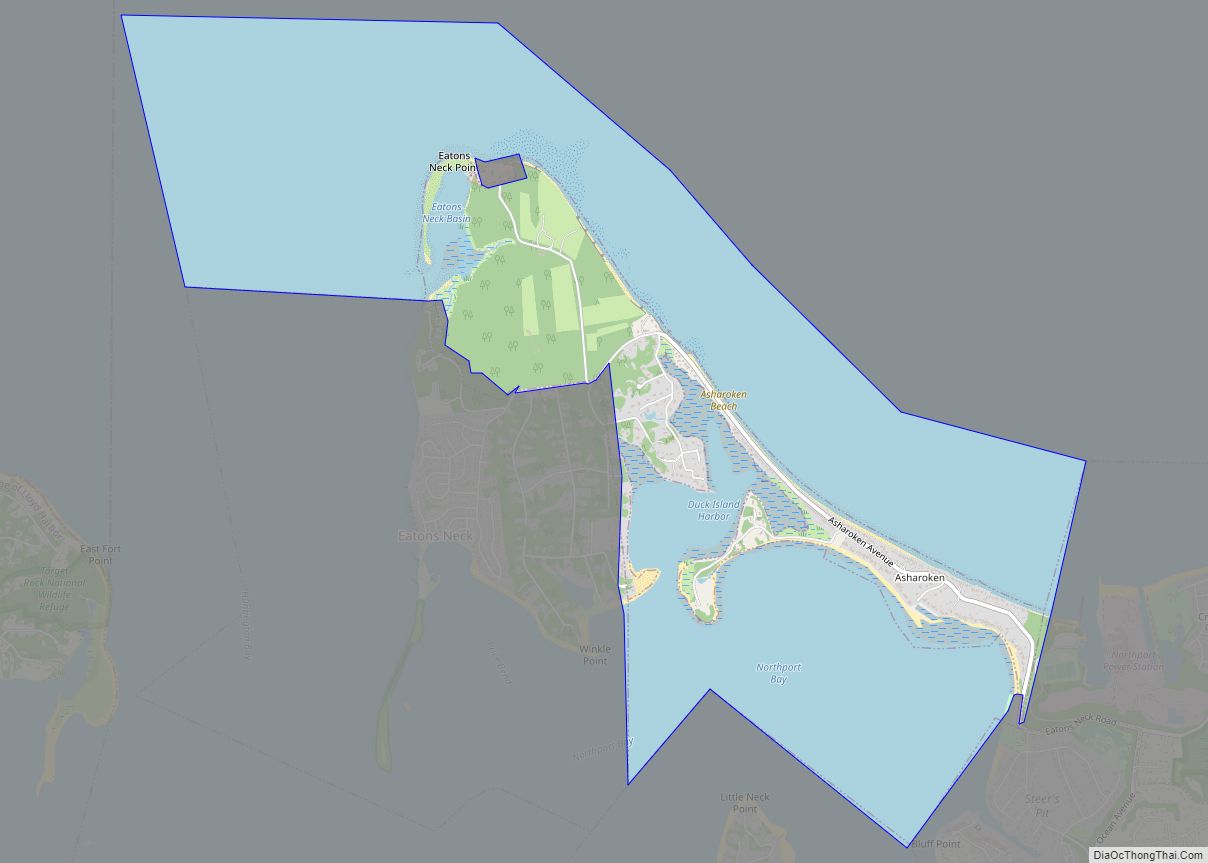

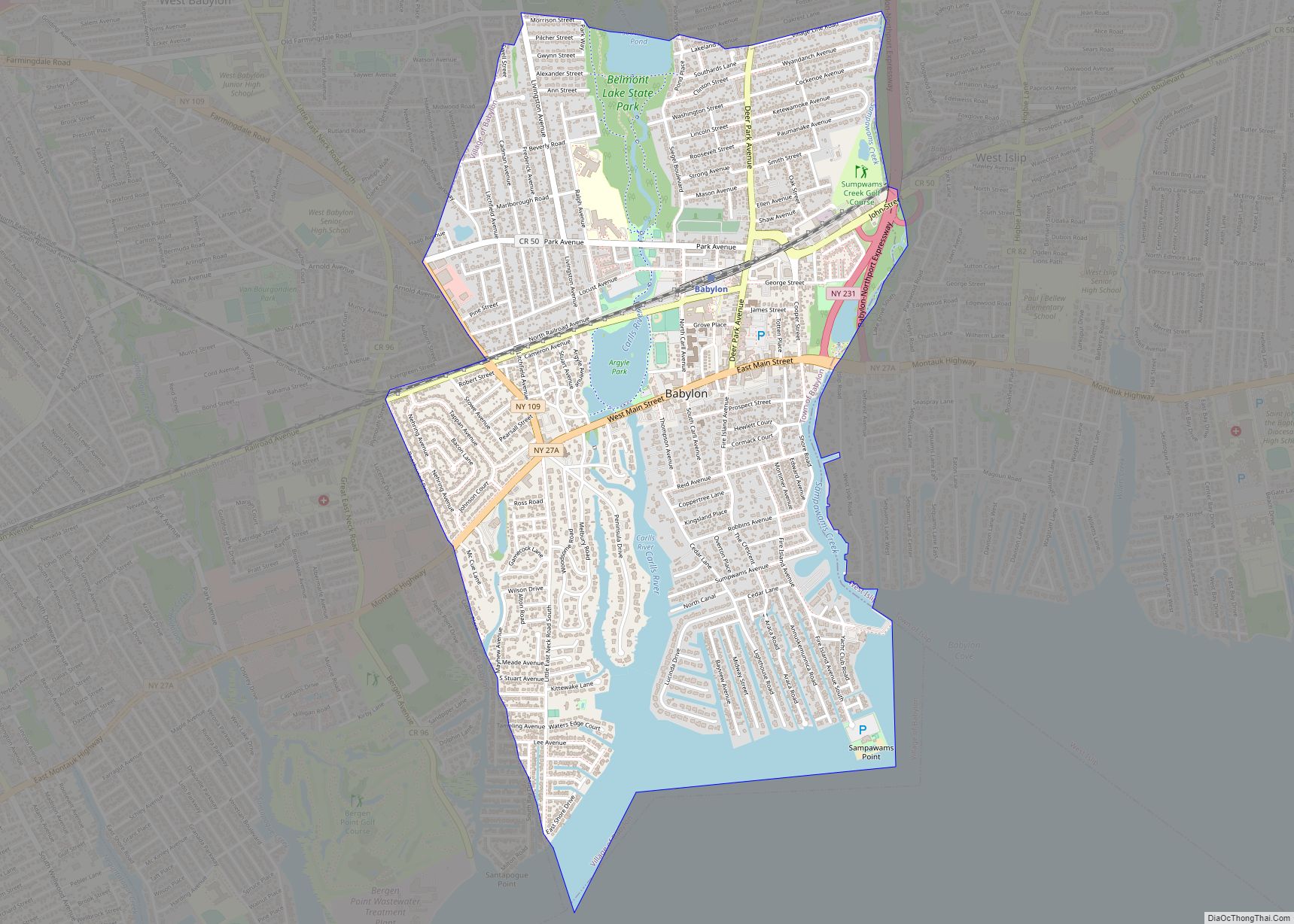

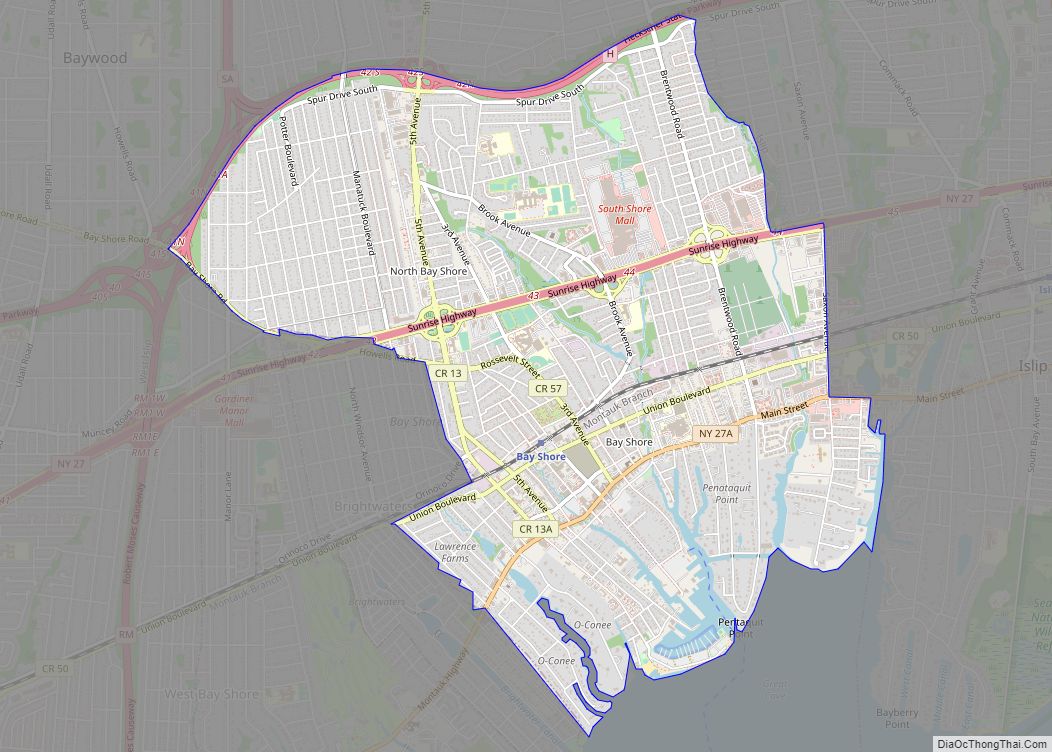

Fire Island is part of Suffolk County. It lies within the towns of Babylon, Islip, and Brookhaven, containing two villages and a number of hamlets. All parts of the island not within village limits are part of the Fire Island census-designated place (CDP), which had a permanent population of 292 at the 2010 census, though that expands to thousands of residents and tourists during the summer months.

| Name: | Fire Island CDP |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 57 |

| LSAD Description: | CDP (suffix) |

| State: | New York |

| County: | Suffolk County |

| FIPS code: | 3625839 |

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

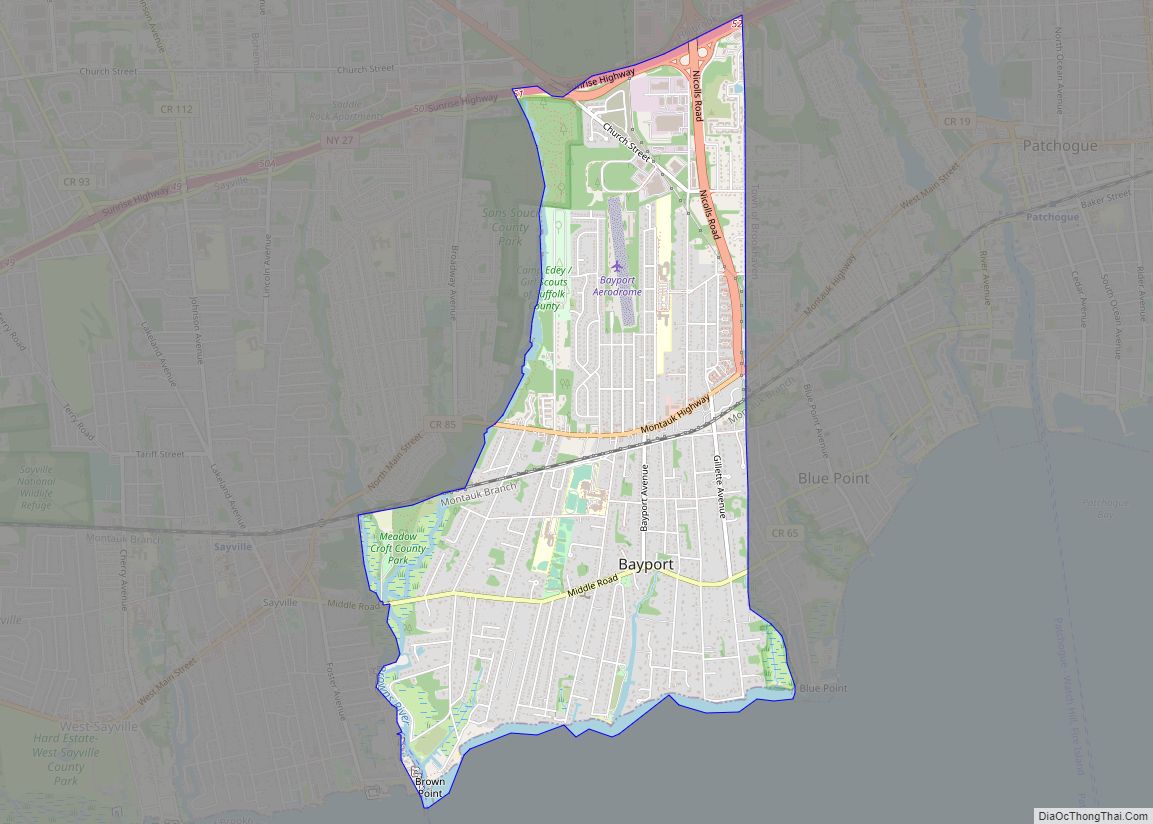

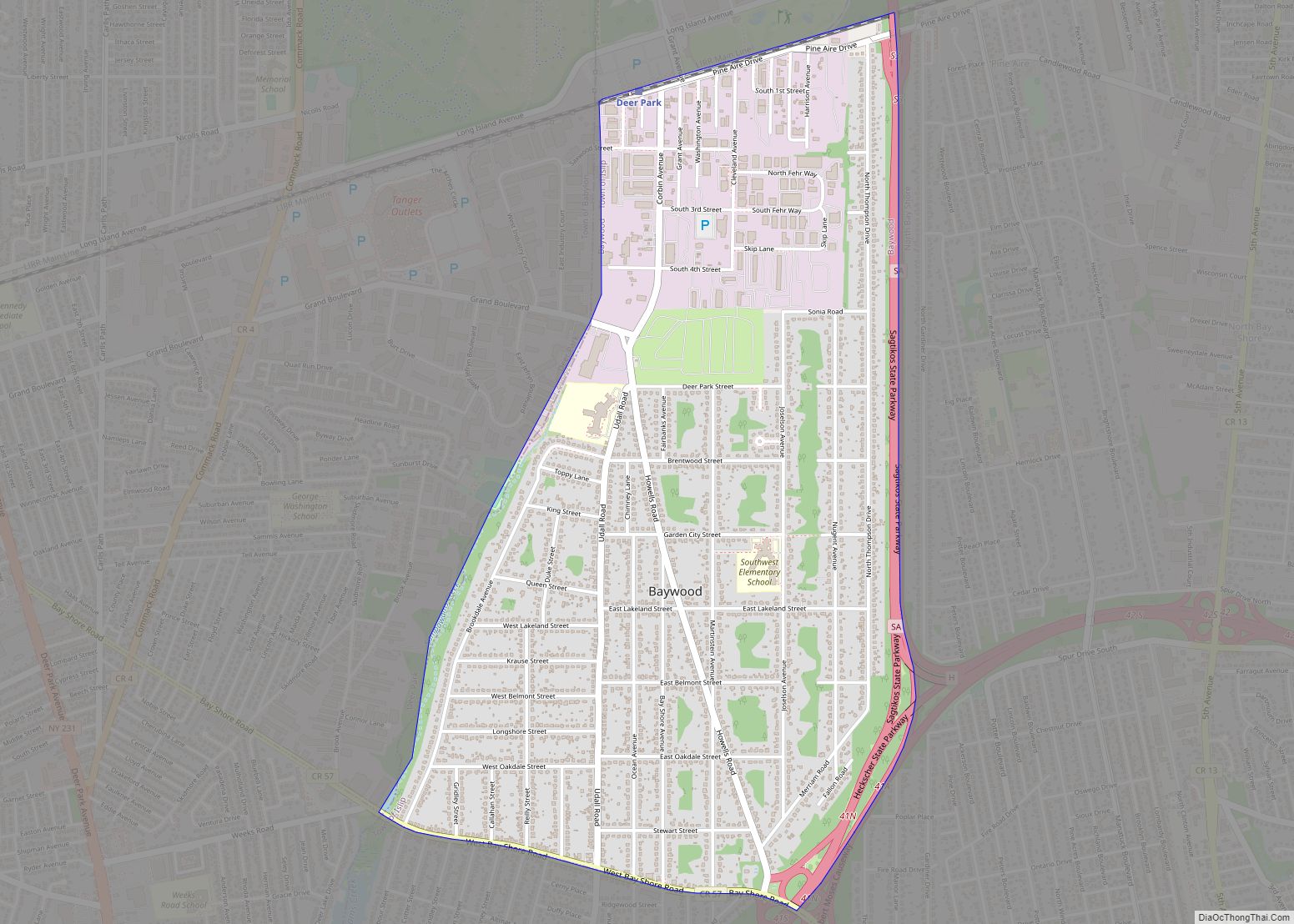

Fire Island location map. Where is Fire Island CDP?

History

Etymology

The origin of Fire Island’s name is not certain. It is believed its Native American name was Sictem Hackey, which translated to “Land of the Secatogues”. The Secatogues were a tribe in the area of the current town of Islip. It was part of what was also called the “Seal Islands”.

The name of Fire Island first appeared on a deed in 1789.

Historian Richard Bayles suggested that the name derives from a misinterpretation or corruption of the Dutch word vijf (‘five’), or in another version vier (‘four’), referring to the number of islands near the Fire Island inlet, a view echoed by Robert Caro, who suggest in The Power Broker that the island was named to reflect four inlets which have since disappeared. At times histories have referred to it in the plural, as “Fire Islands”, because of the inlet breaks.

Other versions say the island derived its name from fires built on the sea’s edge by Native Americans or by pirates to lure unsuspecting ships into the sandbars. Some say it is how portions of the island look to be on fire from sea in autumn. Yet another version says it comes from the rash caused by poison ivy on the island.

While the western portion of the island was referred to as Fire Island for many years, the eastern portion was referred to as Great South Beach until 1920, when widespread development caused the whole land mass to be called Fire Island.

Settlement

Indigenous Native Americans lived on what are known today as Long Island and Fire Island for many centuries before Europeans arrived. There exists a myth that the islands were occupied by “thirteen tribes” “neatly divided into thirteen tribal units, beginning with the Canarsie who lived in present-day Brooklyn and ending with the Montauk on the far eastern end of the island.” Modern ethnographic research indicates, however, that before the European invasion, Long Island and Fire Island were occupied by “indigenous groups […] organized into village systems with varying levels of social complexity. They lived in small communities that were connected in an intricate web of kinship relations […] there were probably no native peoples living in tribal systems on Long Island until after the Europeans arrived. […] The communities appear to have been divided into two general culture areas that overlapped in the area known today as the Hempstead Plains […]. The western groups spoke the Delaware-Munsee dialect of Algonquian and shared cultural characteristics such as the longhouse system of social organization with their brethren in what is now New Jersey and Delaware. The linguistic affiliation of the eastern groups is less well understood […] Goddard […] concluded that the languages here are related to the southern New England Algonquian dialects, but he could only speculate on the nature of these relationships […]. Working with a few brief vocabulary lists of Montauk and Unquachog, he suggested that the Montauk might be related to Mohegan-Pequot and the Unquachog might possibly be grouped with the Quiripi of western Connecticut. The information on the Shinnecock was too sparse for any determination […] The most common pattern of indigenous life on Long Island prior to the intervention of the whites was the autonomous village linked by kinship to its neighbors.”

“Most of the ‘tribal’ names with which we are now familiar do not appear to have been recognized by either the first European observers or by the original inhabitants until the process of land purchases began after the first settlements were established. We simply do not know what these people called themselves, but all the ethnographic data on North American Indian cultures suggest that they identified themselves in terms of lineage and clan membership. […] The English and Dutch were frustrated by this lack of structure because it made land purchase so difficult. Deeds, according to the European concept of property, had to be signed by identifiable owners with authority to sell and have specific boundaries on a map. The relatively amorphous leadership structure of the Long Island communities, the imprecise delineation of hunting ground boundaries, and their view of the land as a living entity to be used rather than owned made conventional European real estate deals nearly impossible to negotiate. The surviving primary records suggest that the Dutch and English remedied this situation by pressing cooperative local sachems to establish a more structured political base in their communities and to define their communities as “tribes” with specific boundaries […] The Montauk, under the leadership of Wyandanch in the mid-seventeenth century, and the Matinnecock, under the sachems Suscaneman and Tackapousha, do appear to have developed rather tenuous coalitions as a result of their contact with the English settlers.”

“An early example of [European] intervention into Native American political institutions is a 1664 agreement wherein the East Hampton and Southampton officials appointed a sunk squaw named Quashawam to govern both the Shinnecock and the Montauk.”

- William “Tangier” Smith held title to the entire island in the 17th century, under a royal patent from Thomas Dongan. The remnants of Smith’s Manor of St. George are open to the public in Shirley, New York. “On May 25, 1691 Col. William “Tangier” Smith purchased from the Indian, John Mayhew the enormous acreage, later to be known as the Manor of St. George. He then set aside 175 acres of the land occupied by the Unkechaug Indians on the west side of the Mastic (Forge) River at Poosepatuck Creek to be theirs for the annual rent of two ears of corn. The Poosepatuck Indian Reservation is still in existence today, however it has shrunk to 55 acres due to unscrupulous land dealings by early officials.”

- The first large house was built in 1795 in Cherry Grove by Jeremiah Smith. Smith was said to have lured ships to their doom and killed the crews.

- In the early 19th century when slavery in New York was still legal, slave runners built stockades on the island by the Fire Island Inlet.

- The first Fire Island Lighthouse was built in 1825 and was replaced by the current lighthouse in 1858.

- In 1855, David S. S. Sammis bought 120 acres (0.49 km) near the Fire Island Lighthouse and built the Surf Hotel at what today is Kismet. Sammis operated the hotel until 1892, when the state took it over. In 1908, it became the first state park on Long Island.

- In 1868, Archer and Elizabeth Perkinson bought the land around Cherry Grove and Fire Island Pines. They built a hotel in 1880.

- In 1887, the Coast Guard established 11 staffed lifesaving stations on the island.

- In 1892, troops were called out to suppress a potential riot at Democrat Point over a cholera panic.

- In 1908, Ocean Beach was established, followed by Saltaire in 1910.

- In 1921, the Perkinsons sold the land around Cherry Grove in small lots. Bungalows from the newly closed Camp Upton in Yaphank were ferried over the Great South Bay to build the new community. Duffy’s Hotel was built in 1930.

- The Great Hurricane of 1938 devastated much of the island and made it appear undesirable to many. However, Duffy’s Hotel remained relatively undamaged. According to legend, the gay population began to concentrate in Cherry Grove at Duffy’s Hotel with Christopher Isherwood and W. H. Auden dressed as Dionysus and Ganymede and carried aloft on a gilded litter by a group of singing followers. The gay influence was continued in the 1960s when male model John B. Whyte developed Fire Island Pines. The Pines currently has some of the most expensive property on the island and accounts for two-thirds of the island’s swimming pools.

- In 1964, Robert Moses built the Captree Causeway to the western end of the island. Opponents, fearing that this was the beginning of plans for the continuation of Ocean Parkway, which would have run down the middle of the island, organized and eventually stopped the parkway.

- In September 1964, Lyndon Johnson signed a bill creating Fire Island National Seashore.

As gay village

The hamlets of Cherry Grove and Fire Island Pines together have constituted a gay village since the mid-20th century. The party-filled culture of the pre-HIV/AIDS 1970s is portrayed in Andrew Holleran’s 1978 novel Dancer from the Dance. The Botel (today the Grove Hotel) was gay-friendly and ran popular afternoon “tea dances”. Cherry Grove calls itself “America’s First Gay and Lesbian Town”. Fire Island has “an iconic gay scene” and the Grove Hotel is the only hotel in New York State that prohibits those under 21 on the premises; this is legal because the hotel’s entrance is through a bar.

2009: Beach renourishment

A 2009 beach renourishment program was credited with saving the island from the full effects of Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

In the winter and spring of 2009, a beach renourishment project was undertaken on Fire Island, with the cooperation of the National Park Service, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Towns of Brookhaven and Islip, and Fire Island residents. The renourishment program involved dredging sand from an offshore borrow area, pumping it onto the beach and shaping the sand into an approved beach face and dune template in front of the communities of Corneille Estates, Davis Park, Dunewood, Fair Harbor, Fire Island Pines, Fire Island Summer Club, Lonelyville, Ocean Bay Park, Ocean Beach, Saltaire, and Seaview. Fire Islanders agreed to a significant property tax increase to help pay for the project, which was estimated to cost between $23 and $25 million ($6,020 per housing unit), including the cost of environmental monitoring, and was expected to add 1,400,000 cubic meters (1,800,000 cubic yards) of sand in front of the participating communities. The Towns of Brookhaven and Islip, in which the communities are located, issued bonds to pay for the project, backed by the new taxes levied by community Erosion Control Taxing Districts.

2012: Hurricane Sandy

The island was heavily damaged in the high tides associated with Hurricane Sandy in 2012, including three breaches around Smith Point County Park on the sparsely populated eastern end of the island. The biggest breach (and politically most difficult one to deal with because it is in a wilderness area) is at Old Inlet in the Otis Pike Wilderness Area just west of Smith Point County Park. Old Inlet is at the site of previous breaches (which have come and gone on their own) and was 108 feet wide after the storm on the south end and 1,171 feet on February 28, 2013. Officials have been debating whether to close the breach and let nature take its course, as it has been flushing out the Great South Bay and improving water quality. However, residents of the bay front communities noted increased flooding after the storm. This flooding was later found to be the result of several nor’easters and unrelated to the breaches. As of 2018, the breach remained open. Officials have moved to close the other two breaches which are on either side of Moriches Inlet—one in Cupsogue County Park and the other being in Smith Point County Park.

Reports indicated that 80 percent of the homes, particularly those on the east end, were flooded, and 90 homes were completely destroyed. The storm also tore away about 75 feet of the dune coastline. But Fire Island was not hit as hard as other areas, with most of the 4,500 homes on the island surviving even if damaged, and significant home reconstruction has taken place. Officials credited the dune replenishment program with helping to spare the island.

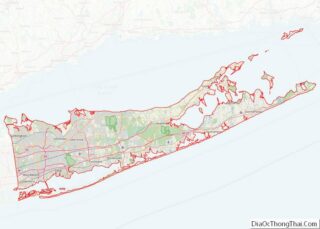

Fire Island Road Map

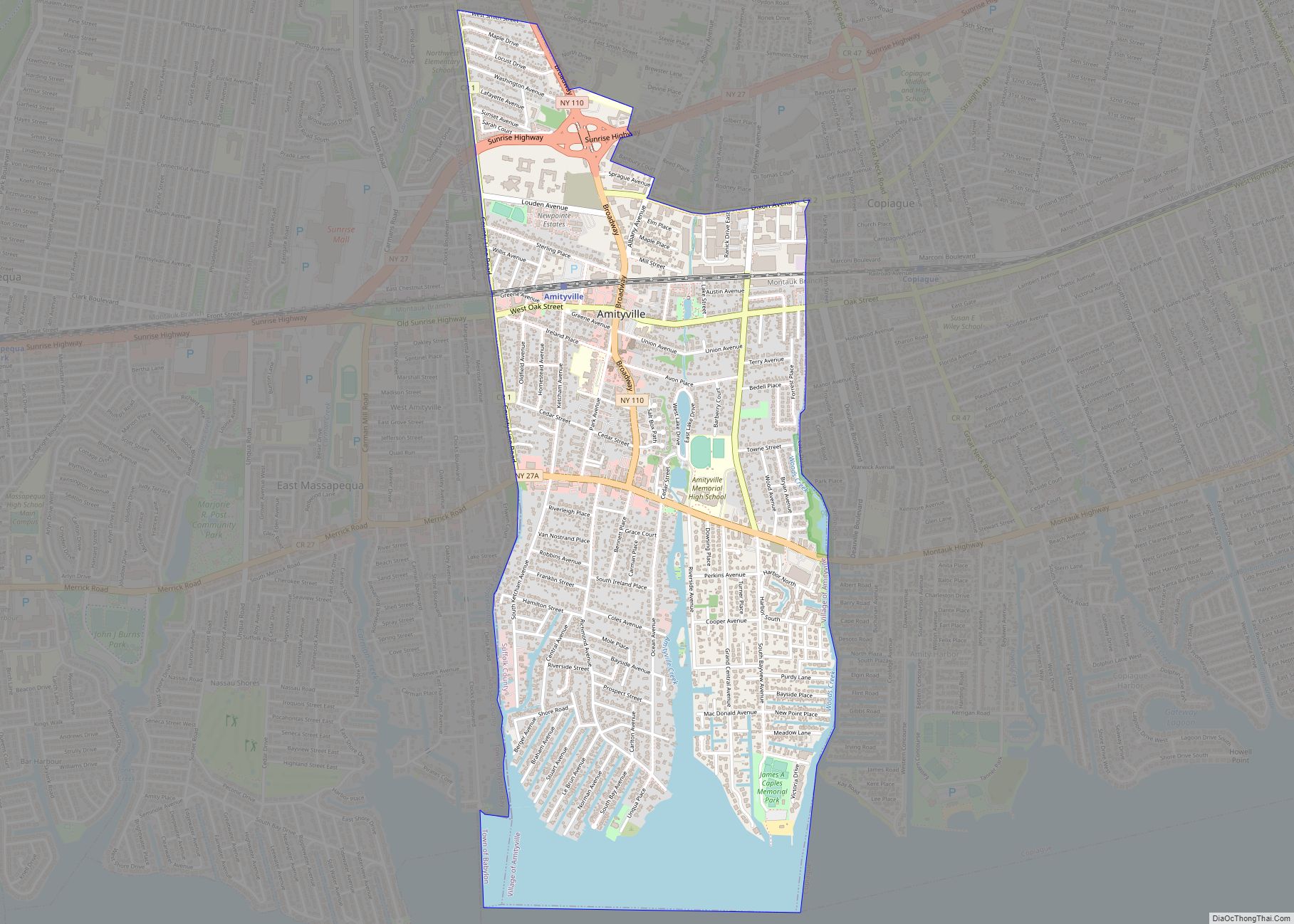

Fire Island city Satellite Map

Geography

Fire Island lies on average 3.9 miles (6.2 km) off the South Shore of Long Island, but nearly touches it along the East End. It is separated from Long Island by the Great South Bay, which spans interconnected bays along Long Island: Patchogue Bay, Bellport Bay, Narrow Bay, and Moriches Bay.

The island and its resort communities are accessible by boat, seaplane, and a number of ferries, which run across the bay from Patchogue, Bay Shore, and Sayville, to more than 10 points on the island.

The island is accessible by automobile near each end: via Robert Moses Causeway on its western end, and by William Floyd Parkway (Suffolk County Road 46) near its eastern end. Motor vehicles are not permitted on the rest of the island, except for utility, construction and emergency access and with limited beach-driving permits in winter.

Fire Island is located at 40°39′35″ north, 73°5′23″ west (40°39′11″N 73°07′34″W / 40.653°N 73.126°W / 40.653; -73.126Coordinates: 40°39′11″N 73°07′34″W / 40.653°N 73.126°W / 40.653; -73.126). According to the United States Census Bureau, Fire Island has a land area of 9.6 square miles (24.9 km).

History of American cartography and international metrology

In 1834, Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler, a Swiss-American surveyor, measured at Fire Island the first baseline of the Survey of the Coast, shortly before Louis Puissant declared, in 1836, to the French Academy of Sciences that Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre and Pierre Méchain had made errors in the meridian arc measurement, which had been used for determining the length of the metre. Hassler had designed a baseline apparatus which instead of bringing different bars in actual contact during measurements, used only one bar calibrated on the metre and optical contact.

At that time in Europe, surveyors continued to use measuring instruments calibrated on the Toise of Peru. In 1840, Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel questioned the accuracy of three copies of this standard belonging to Altona and Koenigsberg Observatories, which he had compared to each other. Next year, Bessel proposed his ellipsoid of reference and a flattening of the Earth much closer to reality than that which had been used to compute the length of the metre from the arc measurement of Delambre and Méchain.

Geodesists were the first to demand the creation of an international institute for the comparison of length standards. According to Charles Édouard Guillaume, the consideration of a discrepancy between the Toise of Peru and the Toise of Bessel led the Central European Arc Measurement to consider, at its 1866 meeting in Neuchâtel, where Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero proposed the participation of Spain to remeasure and extend the meridian arc of Paris, the foundation of a World institute for the comparison of geodetic standards, the first step towards the creation of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures.

Historical modifications

The physical attributes of the island have changed over time, and they continue to change. At one point it stretched more than 60 miles (97 km) from Jones Beach Island to Southampton.

Around 1683, Fire Island Inlet broke through, separating it from Jones Beach Island.

The Fire Island Inlet grew to 9 miles (14 km) in width before receding. The Fire Island Lighthouse was built in 1858, right on the inlet, but Fire Island’s western terminus at Democrat Point has steadily moved west so that the lighthouse today is 6 miles (10 km) from the inlet.

Fire Island separated from Southampton in a 1931 Nor’easter when Moriches Inlet broke through. However, this is expected. The inlet widened on September 21, 1938. Moriches Inlet and efforts by local communities east of Fire Island to protect their beach front with jetties have led to an interruption in the longshore drift of sand going from east to west and are blamed for erosion of the Fire Island beachfront. Between these major breaks there have been reports over the years of at least six inlets that broke through the island but have since disappeared.

See also

Map of New York State and its subdivision:- Albany

- Allegany

- Bronx

- Broome

- Cattaraugus

- Cayuga

- Chautauqua

- Chemung

- Chenango

- Clinton

- Columbia

- Cortland

- Delaware

- Dutchess

- Erie

- Essex

- Franklin

- Fulton

- Genesee

- Greene

- Hamilton

- Herkimer

- Jefferson

- Kings

- Lake Ontario

- Lewis

- Livingston

- Madison

- Monroe

- Montgomery

- Nassau

- New York

- Niagara

- Oneida

- Onondaga

- Ontario

- Orange

- Orleans

- Oswego

- Otsego

- Putnam

- Queens

- Rensselaer

- Richmond

- Rockland

- Saint Lawrence

- Saratoga

- Schenectady

- Schoharie

- Schuyler

- Seneca

- Steuben

- Suffolk

- Sullivan

- Tioga

- Tompkins

- Ulster

- Warren

- Washington

- Wayne

- Westchester

- Wyoming

- Yates

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming