Toledo (/təˈliːdoʊ/ tə-LEE-doh) is a city in and the county seat of Lucas County, Ohio, United States. At the 2020 census, it had a population of 270,871, making Toledo the fourth-most populous city in the state of Ohio, after Columbus, Cleveland, and Cincinnati. Toledo is also the 79th-largest city in the United States. It is principal city of the Toledo metropolitan area, which had 646,604 residents in 2020. Toledo also serves as a major trade center for the Midwest; its port is the fifth-busiest on the Great Lakes.

The city was founded in 1833 on the west bank of the Maumee River and originally incorporated as part of the Michigan Territory. It was refounded in 1837 after the conclusion of the Toledo War, when it was incorporated in Ohio. After the 1845 completion of the Miami and Erie Canal, Toledo grew quickly; it also benefited from its position on the railway line between New York City and Chicago. The first of many glass manufacturers arrived in the 1880s, eventually earning Toledo its nickname as “The Glass City”. Downtown Toledo has been subject to major revitalization efforts, including a growing entertainment district.

| Name: | Toledo city |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 25 |

| LSAD Description: | city (suffix) |

| State: | Ohio |

| County: | Lucas County |

| Founded: | 1837 |

| Elevation: | 614 ft (187 m) |

| Land Area: | 80.49 sq mi (208.46 km²) |

| Water Area: | 3.34 sq mi (8.66 km²) |

| Population Density: | 3,365.36/sq mi (1,299.38/km²) |

| FIPS code: | 3977000 |

| Website: | www.toledo.oh.gov |

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

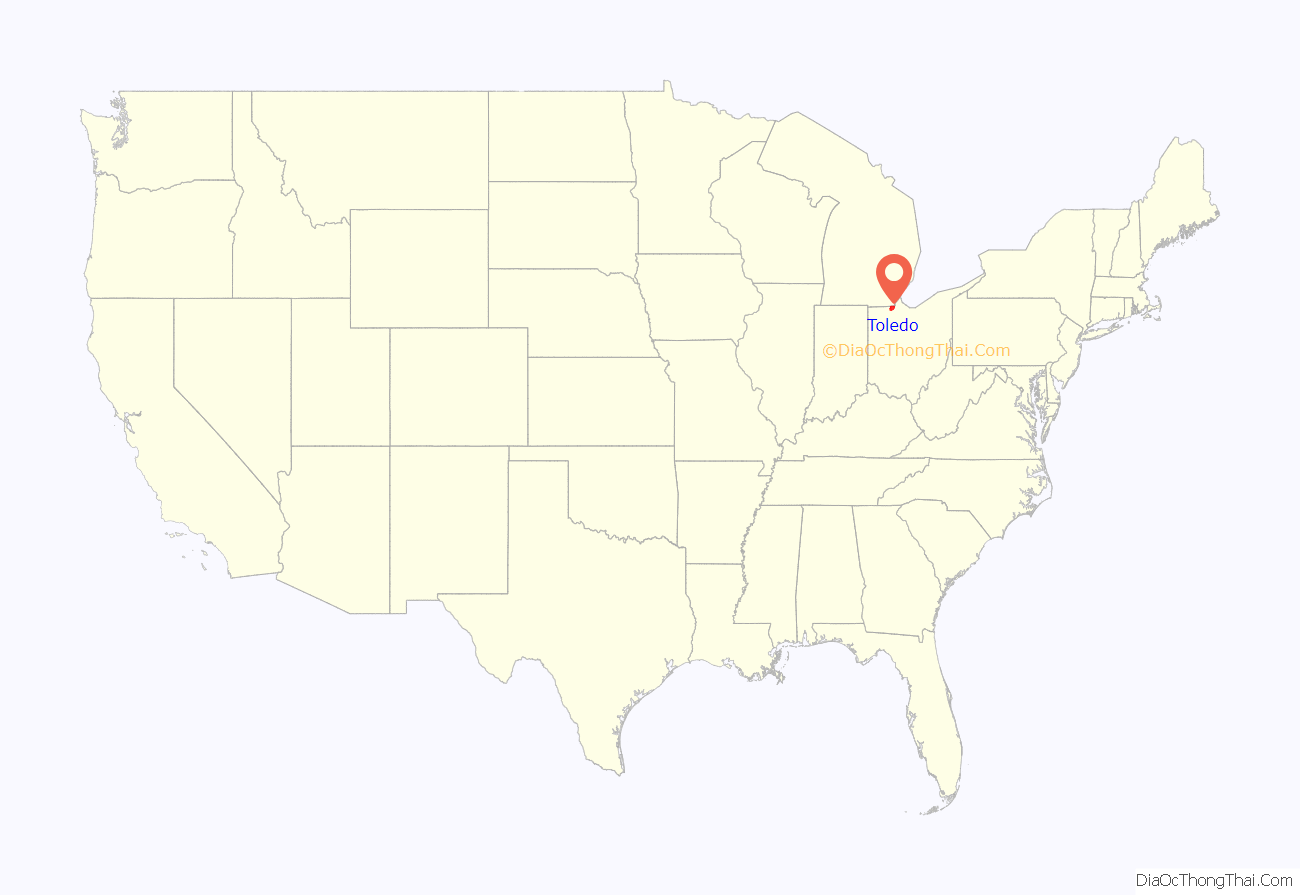

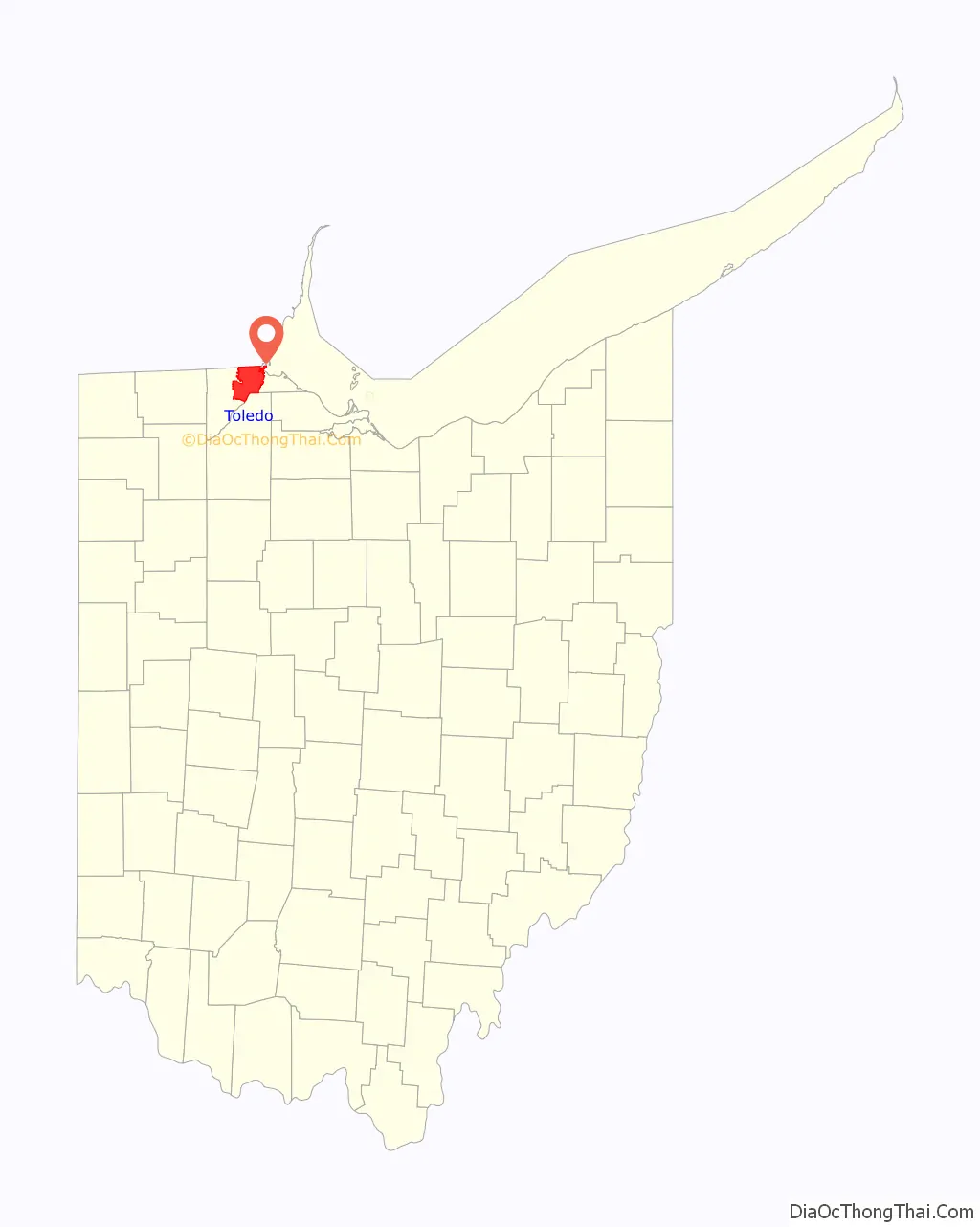

Toledo location map. Where is Toledo city?

History

The region was part of a larger area controlled by the historic tribes of the Wyandot and the people of the Council of Three Fires (Ojibwe, Potawatomi, and Odawa). The French established trading posts in the area by 1680 to take advantage of the lucrative fur trade. The Odawa moved from Manitoulin Island and the Bruce Peninsula at the invitation of the French, who established a trading post at Fort Detroit, about 60 miles to the north. They settled an area extending into northwest Ohio. By the early 18th century, the Odawa-occupied areas along most of the Maumee River to its mouth. They served as middlemen between the French and tribes further to the west and north. The Wyandot occupied central Ohio, and the Shawnee and Lenape occupied the southern areas.

When the city of Toledo was preparing to pave its streets, it surveyed “two prehistoric semicircular earthworks, presumably for stockades.” One was at the intersection of Clayton and Oliver Streets on the south bank of Swan Creek; the other was at the intersection of Fassett and Fort Streets on the right bank of the Maumee River. Such earthworks were typical of mound-building peoples.

19th century

According to Charles E. Slocum, the American military built Fort Industry at the mouth of Swan Creek about 1805, as a temporary stockade. No official reports support the 19th-century tradition of its earlier history there.

The United States continued to work to transition the area’s population from native Americans to Whites. In the Treaty of Detroit (1807), the above four tribes ceded a large land area to the United States of what became southeastern Michigan and northwestern Ohio, to the mouth of the Maumee River (where Toledo later developed). Reserves for the Odawa were set aside in northwestern Ohio for a limited time. The Indian signed the treaty at Detroit, Michigan, on November 17, 1807, with William Hull, governor of the Michigan Territory and superintendent of Indian affairs, as the sole representative of the U.S.

More American settlers entered the area over the next few years, but many fled during the War of 1812, when British forces raided the area with their Indian allies. Resettlement began around 1818 after a Cincinnati syndicate purchased a 974-acre (3.9 km) tract at the mouth of Swan Creek and named it Port Lawrence, developing it as the modern downtown area of Toledo. Immediately to the north of that, another syndicate founded the town of Vistula, the historic north end. These two towns bordered each other across Cherry Street. This is why present-day streets on the street’s northeast side run at a slightly different angle from those southwest of it.

In 1824, the Ohio state legislature authorized the construction of the Miami and Erie Canal, and in 1833, its Wabash and Erie Canal extension. The canal’s purpose was to connect the city of Cincinnati to Lake Erie for water transportation to eastern markets, including to New York City via the Erie Canal and Hudson River. At that time, no highways had been built in the state, and goods produced locally had great difficulty reaching the larger markets east of the Appalachian Mountains. During the canal’s planning phase, many small towns along the northern shores of the Maumee River heavily competed to be the ending terminus of the canal, knowing it would give them a profitable status. The towns of Port Lawrence and Vistula merged in 1833 to better compete against the upriver towns of Waterville and Maumee.

The inhabitants of this joined settlement chose the name Toledo:

Despite Toledo’s efforts, the canal built the final terminus in Manhattan, one-half mile (800 m) to the north of Toledo, because it was closer to Lake Erie. As a compromise, the state placed two sidecuts before the terminus, one in Toledo at Swan Creek and another in Maumee, about 10 miles to the southwest.

Among the numerous treaties made between the Ottawa and the United States were two signed in this area: at Miami (Maumee) Bay in 1831 and umee, Ohio, upriver of Toledo, in 1833. These actions were among US purchases or exchanges of land to accomplish Indian Removal of the Ottawa from areas wanted for European-American settlement. The last of the Odawa did not leave this area until 1839, when Ottokee, grandson of Pontiac, led his band from their village at the mouth of the Maumee River to Indian Territory in Kansas.

An almost bloodless conflict between Ohio and the Michigan Territory, called the Toledo War (1835–1836), was “fought” over a narrow strip of land from the Indiana border to Lake Erie, now containing the city and the suburbs of Sylvania and Oregon, Ohio. The strip, which varied between five and eight miles (13 km) in width, was claimed by both the state of Ohio and the Michigan Territory due to conflicting legislation concerning the location of the Ohio-Michigan state line. Militias from both states were sent to the border, but never engaged. The only casualty of the conflict was a Michigan deputy sheriff—stabbed in the leg with a penknife by Two Stickney during the arrest of his elder brother, One Stickney—and the loss of two horses, two pigs, and a few chickens stolen from an Ohio farm by lost members of the Michigan militia. Major Benjamin Franklin Stickney, father of One and Two Stickney, had been instrumental in pushing Congress to rule in favor of Ohio gaining Toledo. In the end, the state of Ohio was awarded the land after the state of Michigan was given a larger portion of the Upper Peninsula in exchange. Stickney Avenue in Toledo is named for Major Stickney.

Toledo was very slow to expand during its first two decades of settlement. The first lot was sold in the Port Lawrence section of the city in 1833. It held 1,205 persons in 1835, and five years later, it had gained just seven more persons. Settlers came and went quickly through Toledo and between 1833 and 1836, ownership of land had changed so many times that none of the original parties remained in the town. The canal and its Toledo sidecut entrance were completed in 1843. Soon after the canal was functional, the new canal boats had become too large to use the shallow waters at the terminus in Manhattan. More boats began using the Swan Creek sidecut than its official terminus, quickly putting the Manhattan warehouses out of business and triggering a rush to move business to Toledo. Most of Manhattan’s residents moved out by 1844.

The 1850 census recorded Toledo as having 3,829 residents and Manhattan 541. The 1860 census shows Toledo with a population of 13,768 and Manhattan with 788. While the towns were only a mile apart, Toledo grew by 359% in 10 years. Manhattan’s growth was on a small base and never competed, given the drawbacks of its lesser canal outlet. By the 1880s, Toledo expanded over the vacant streets of Manhattan and Tremainsville, a small town to the west.

In the last half of the 19th century, railroads slowly began to replace canals as the major form of transportation. They were faster and had greater capacity. Toledo soon became a hub for several railroad companies and a hotspot for industries such as furniture producers, carriage makers, breweries, and glass manufacturers. Large immigrant populations came to the area.

20th century

In the 1920s, Toledo had one of the highest rates of industrial growth in the United States.

Toledo continued to expand in population and industry, but because of its dependence on manufacturing, the city was hit hard by the Great Depression. Many large-scale Works Progress Administration projects were constructed to re-employ citizens in the 1930s. Some of these include the amphitheater and aquarium at the Toledo Zoo and a major expansion to the Toledo Museum of Art.

The postwar job boom and Great Migration brought thousands of African Americans to Toledo to work in industrial jobs, where they had previously been denied. Due to redlining, many of them settled along Dorr Street, which, during the 1950s and 60s was lined with flourishing black-owned businesses and homes. Desegregation, a failed urban renewal project, and the construction of I-75 displaced those residents and left behind a struggling community with minimal resources, even as it also drew more established, middle-class people, white and black, out of center cities for newer housing. The city rebounded, but the slump of American manufacturing in the second half of the 20th century during industrial restructuring cost many jobs.

By the 1980s, Toledo had a depressed economy. The destruction of many buildings downtown, along with several failed business ventures in housing in the core, led to a reverse city-suburb wealth problem common in small cities with land to spare.

21st century

In 2018, Cleveland-Cliffs, Inc. invested $700 million into an East Toledo location as the site of a new hot-briquetted iron plant, designed to modernize the steel industry. The plant was slated to create over 1200 jobs and be completed in 2020.

Several initiatives have been taken by Toledo’s citizens to improve the cityscape by urban gardening and revitalizing their communities. Local artists, supported by organizations like the Arts Commission of Greater Toledo and the Ohio Arts Council, have contributed an array of murals and beautification works to replace long standing blight. Many downtown historical buildings such as the Oliver House and Standart Lofts have been renovated into restaurants, condominiums, offices and art galleries.

Harmful blooms of cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae, were so bad in the 1960s that Lake Erie was mocked as a dead zone. However through clean water rules the lake was revived. Recently though these blooms have returned and have been negatively affecting Lake Erie since the late 1990s now. Heightened levels of blue-green algae can affect both human and ecosystem health by causing fish to die, the water to be discolored and foul smelling, and oxygen deficient dead zones may even start to form. Sometimes the blooms are so thick that they slow boats. These large blooms are caused by agricultural runoff flowing into the lake. Agricultural runoff dumps phosphorus into the western basin of Lake Erie and acts as a fertilizer for the blue-green algae, and the warmer weather seen in July through October in Northern Ohio helps speed up the growing process. Because of Toledo’s closeness to the lake, Toledo citizens are affected each year by these algae blooms.

Lake Erie provides drinking water to many cities along its coast, with Toledo being no exception, and in the summer of 2014 the water flowing into Toledo was thick with algae. On the evening of August 1, 2014 and the morning of August 2nd, 2014 the city of Toledo issued an urgent warning to all citizens in the city and surrounding areas not to drink or use their tap water, this left more than half a million people suddenly without water. Not only was the water unsafe to ingest, but citizens were urged not to even wash their hands or dishes with the water. A bloom of the toxic blue-green algae had formed directly over Toledo’s water intake pipe, which was situated a few miles off shore in Lake Erie. Because of the algae bloom forming just above the pipe, the water being pumped into Toledo showed levels of harmful bacteria that made the water unsafe to interact with.

Because of the urgency of the warnings, it left citizens no time to prepare. The price of bottled water skyrocketed on August 2. With no end date in sight, bottled water flew off the shelves on the day the warning was issued, and in many places it sold out entirely. Some Toledo citizens had to drive for hours just to find safe, clean water, something that many older (14.5% of the population) or low income (24.5% of the population) citizens were unable to do at the time. Churches and other organizations tried to set up water distribution sites, but it was challenging due to the lack of resources.

On the second full day of the crisis, August 3, 2014, churches, schools, and other buildings being used as refuge had run out of water. There was no way for the city to plan for a crisis of this scale, so it took the community by surprise. Later that night, around 4 pm, the National Guard was brought in to deliver over 10,000 gallons of water to citizens. This relieved many people, as bottled water was either sold out in stores or too expensive for the average citizen due to citizens panic buying and stores price gouging. The warning against using water lasted nearly three days, finally ending late on August 4. Fear of tap water still lingered, though.

This event was later dubbed the “Toledo Water Crisis” and is still talked about today, especially during the months that see heightened algal blooms. Algal blooms can cause water bills to increase in this area $100 per year for a family of five. The effects of these blooms go beyond higher water bills as heightened blooms can even shut down parts of the economy such as tourism and fishing industries, and cause property values to drop, costing the local economy to lose tens of millions of dollars. Beyond the economy, the increase in toxic blooms exacts a psychological toll on residents, especially those living near the polluted waterways. Many citizens still find it difficult to trust the local government, and even the tap water, because of the 2014 crisis. Blue-green algae blooms continue to harm Lake Erie even years after the Toledo Water Crisis, but government officials and scientists are both working to find ways to decrease their impact on the environment and the economy.

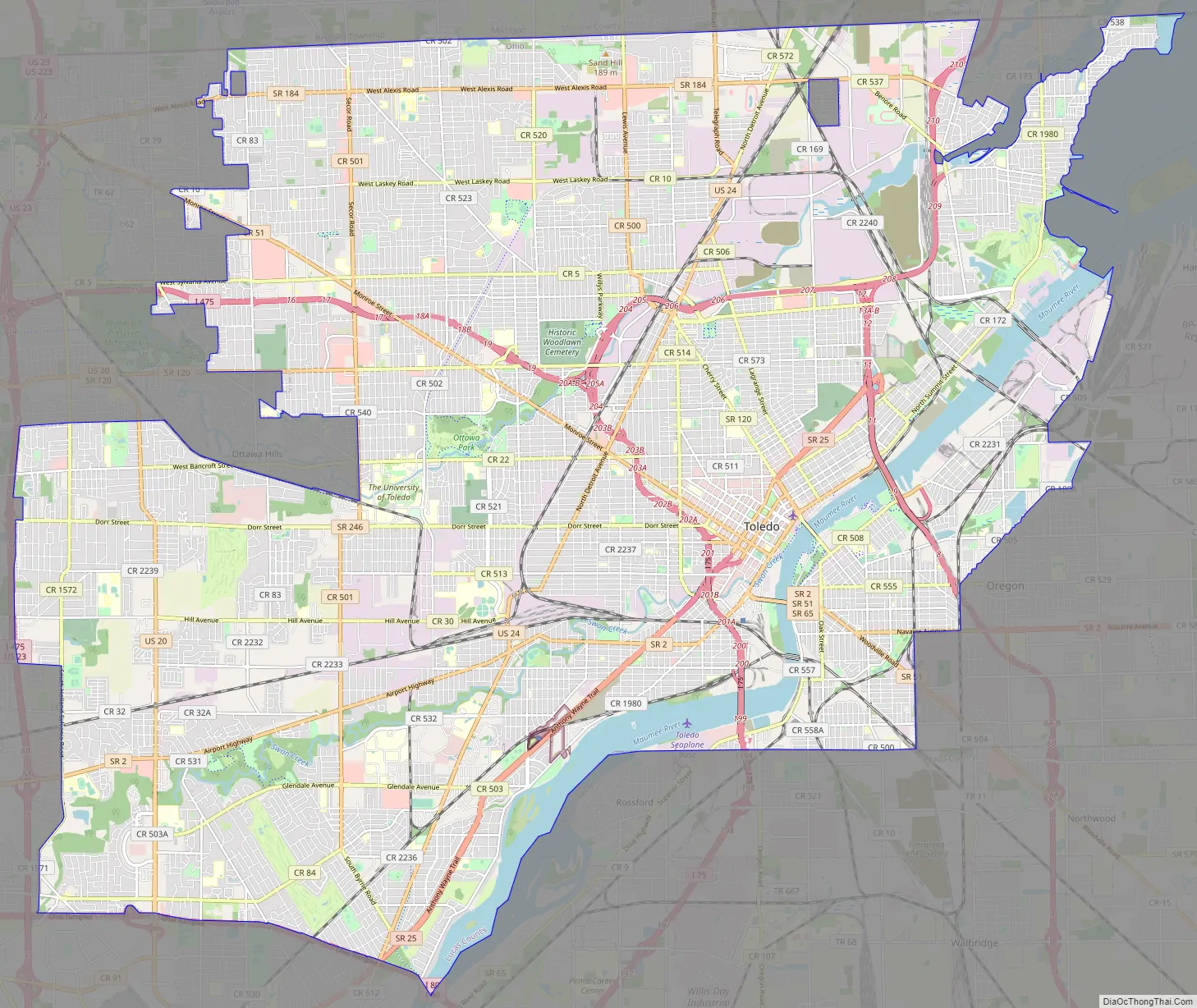

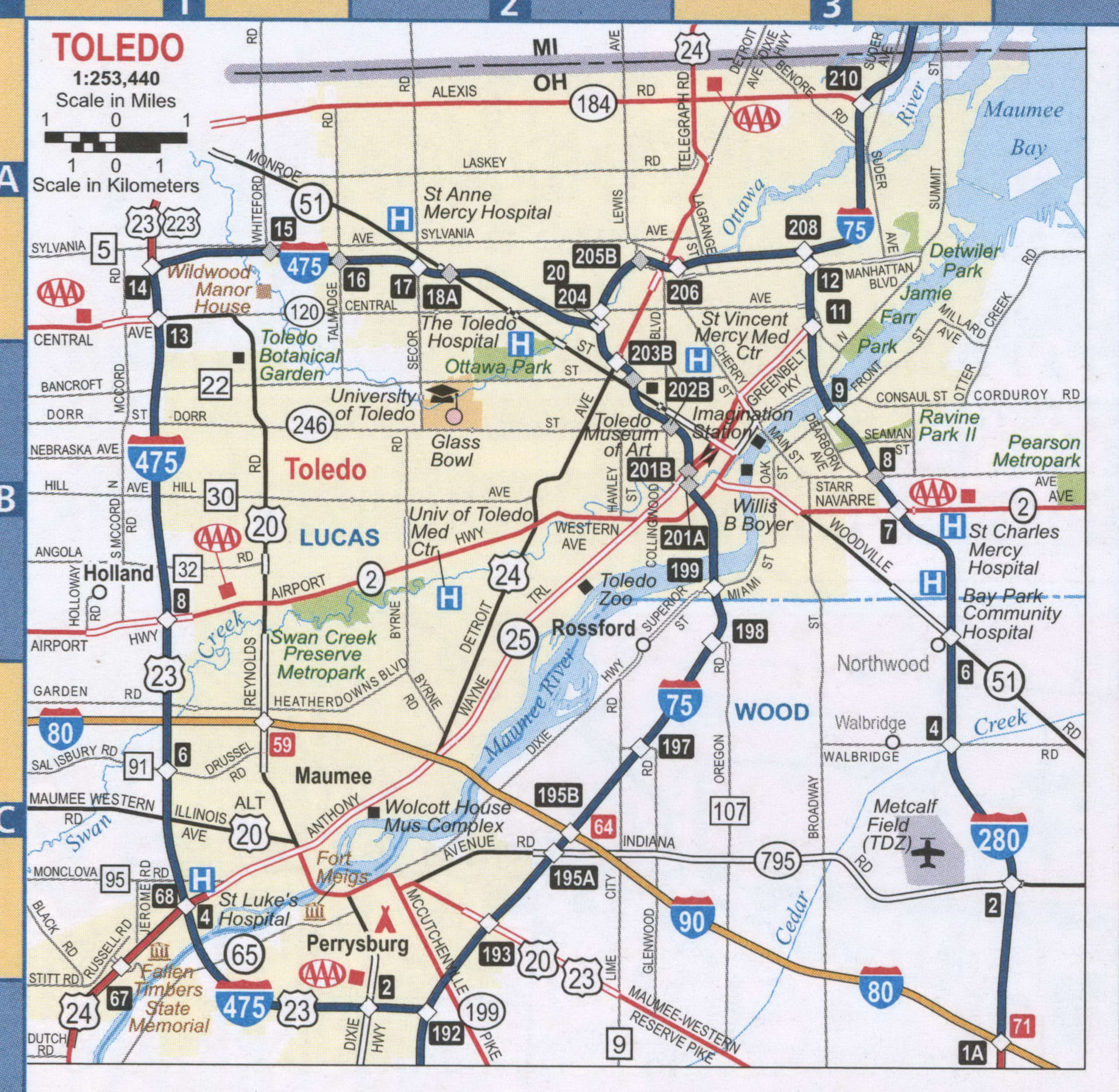

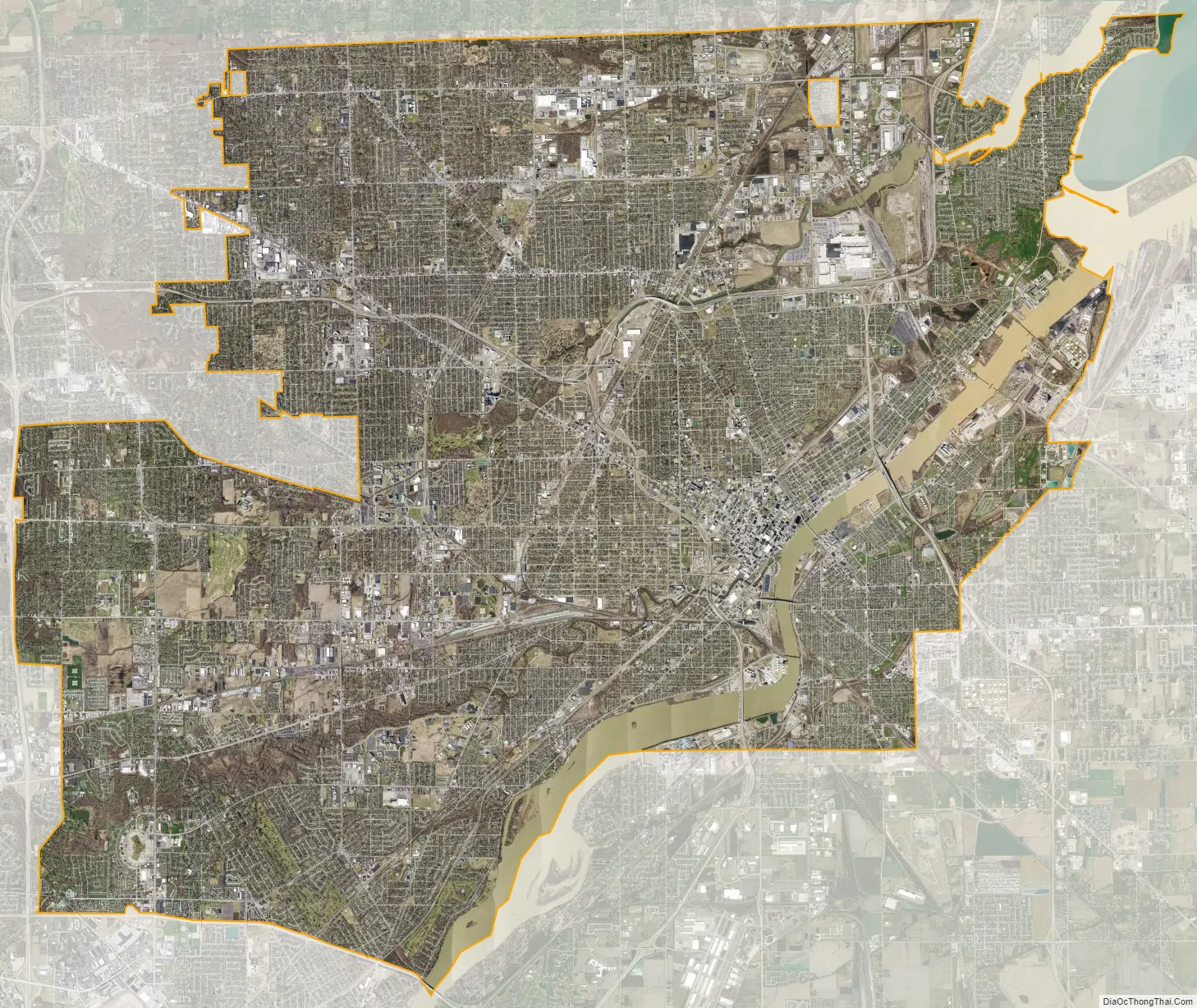

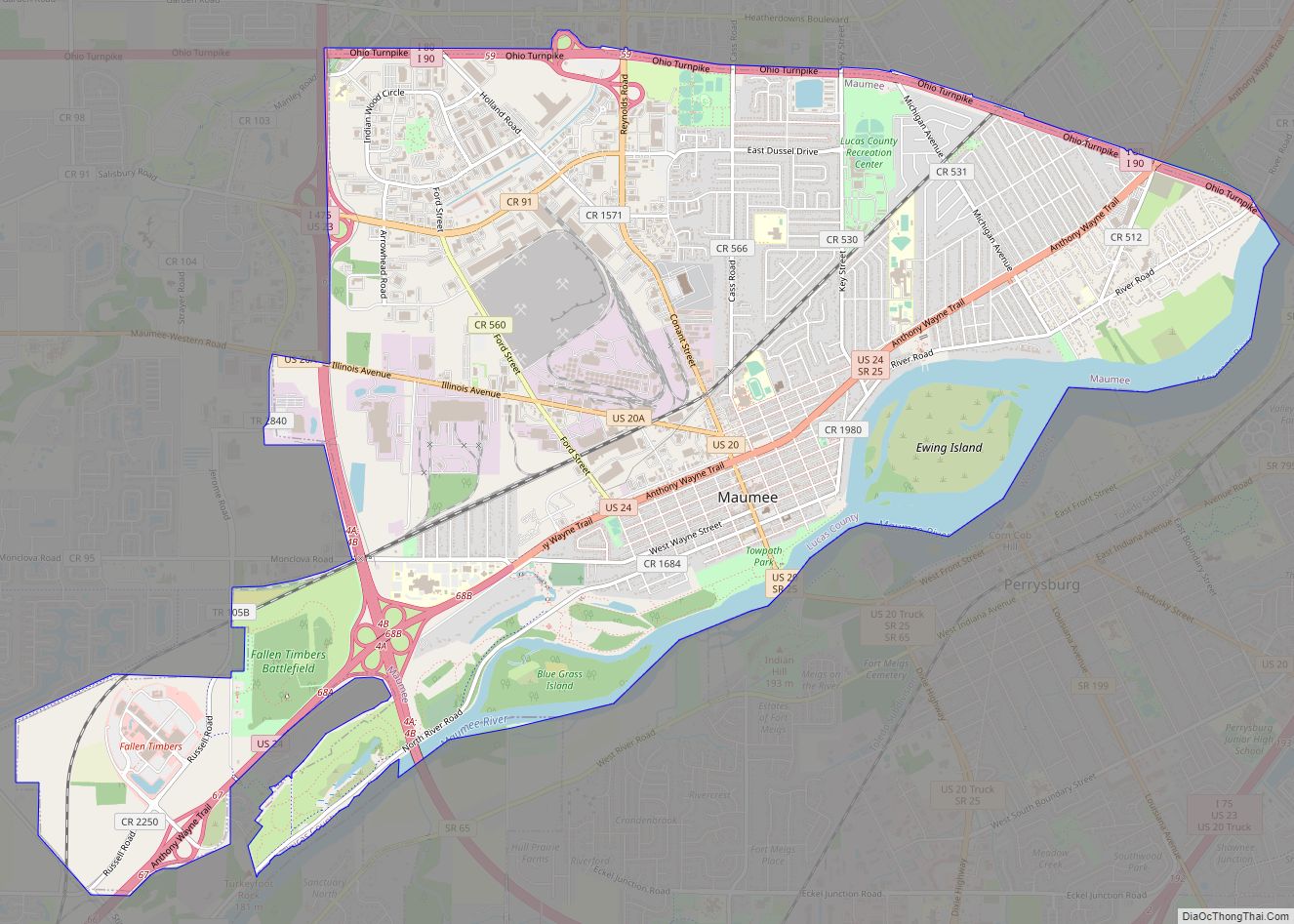

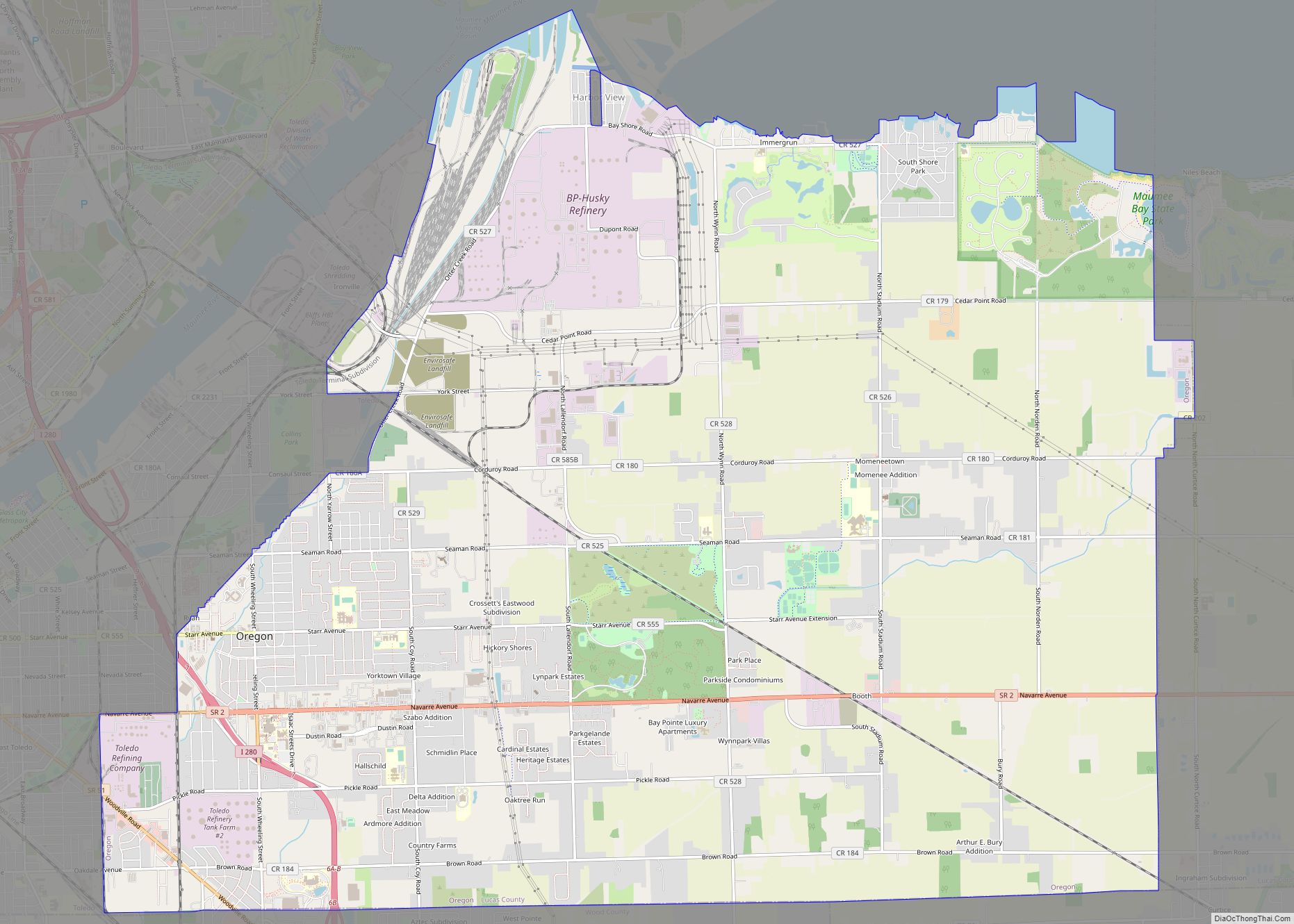

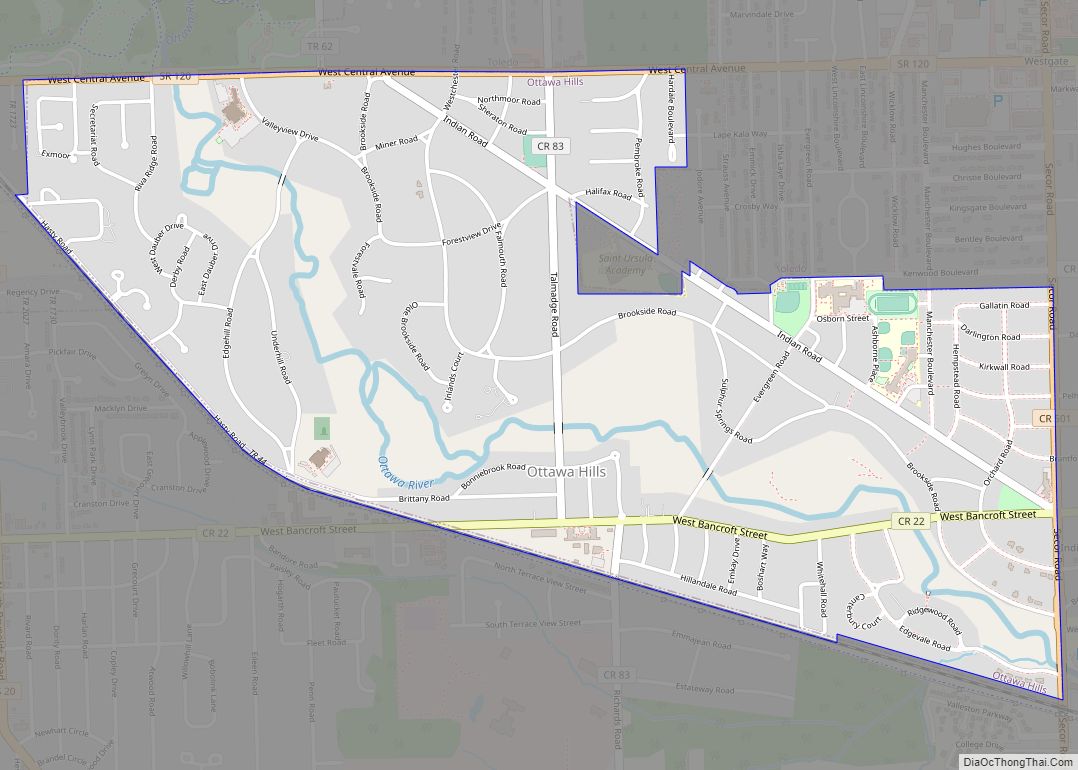

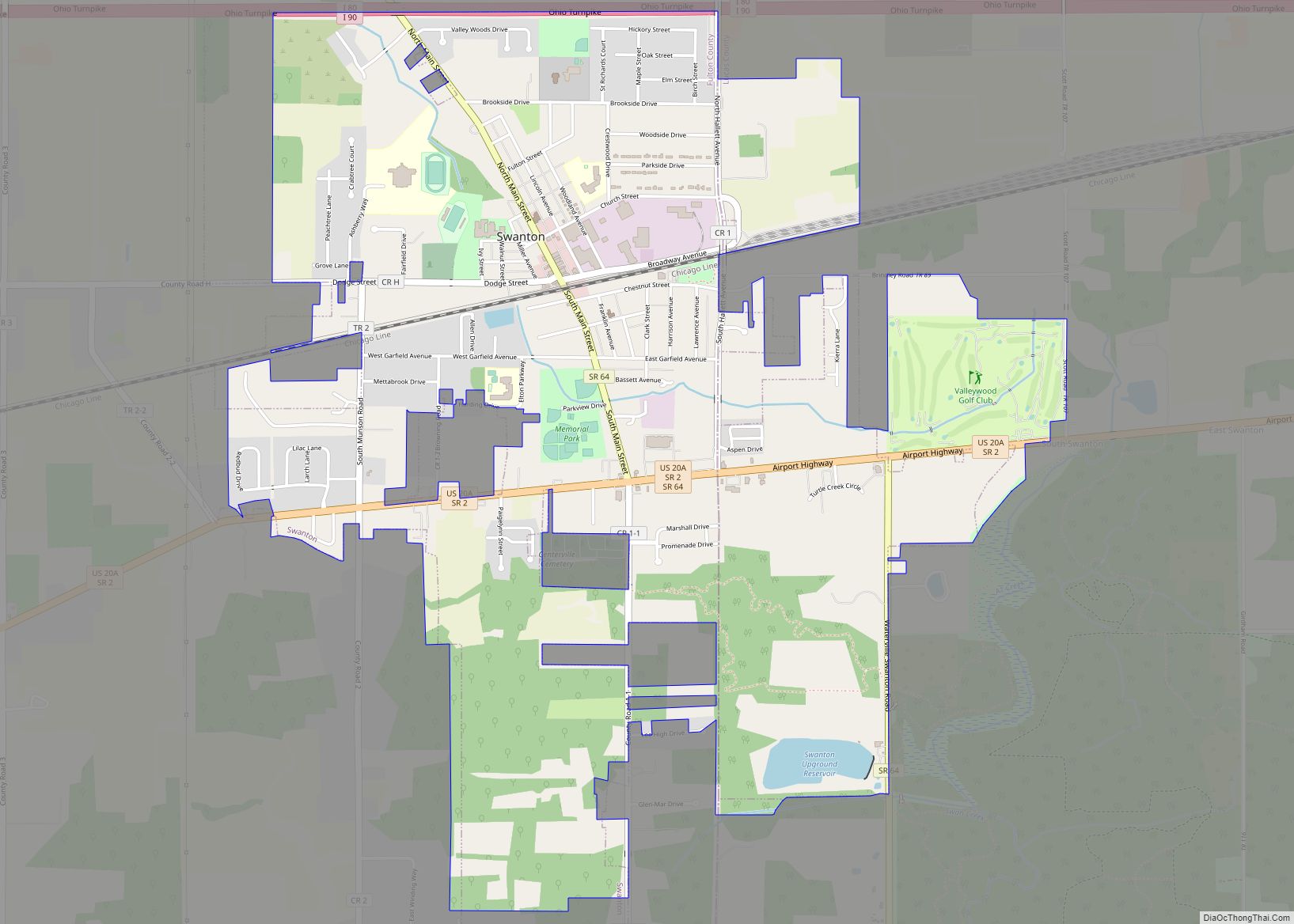

Toledo Road Map

Toledo city Satellite Map

Geography

Toledo is located at 41°39′56″N 83°34′31″W / 41.66556°N 83.57528°W / 41.66556; -83.57528 (41.665682, −83.575337). The city has a total area of 84.12 square miles (217.87 km), of which 3.43 square miles (8.88 km) is covered by water.

The city straddles the Maumee River at its mouth at the southern end of Maumee Bay, the westernmost inlet of Lake Erie. The city is located north of what had been the Great Black Swamp, giving rise to another nickname, Frog Town. Toledo sits within the borders of a sandy oak savanna called the Oak Openings Region, an important ecological site that once comprised more than 300 square miles (780 km).

Toledo is within 250 miles (400 km) by road from seven metropolitan areas that have a population of more than two million people: Detroit, Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, Indianapolis, and Chicago. In addition, it is within 300 miles of Toronto, Ontario.

Climate

Toledo, as with much of the Great Lakes region, has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa), characterized by four distinct seasons. Lake Erie moderates the climate somewhat, especially in late spring and fall, when air and water temperature differences are maximal. However, this effect is lessened in the winter because Lake Erie (unlike the other Great Lakes) usually freezes over, coupled with prevailing winds that are often westerly, and in the summer, prevailing winds south and west over the lake bring heat and humidity to the city.

Summers are very warm and humid, with July averaging 75.4 °F (24.1 °C) and temperatures of 90 °F (32 °C) or more seen on 18.8 days. Winters are cold and somewhat snowy, with a January mean temperature of 27.5 °F (−2.5 °C), and lows at or below 0 °F (−18 °C) on 5.6 nights. The spring months tend to be the wettest time of year, although precipitation is common year-round. November and December can get very cloudy, but January and February usually clear up after the lake freezes. July is the sunniest month overall. About 37 inches (94 cm) of snow falls per year, much less than the Snow Belt cities, because of the prevailing wind direction. Temperature extremes have ranged from −20 °F (−29 °C) on January 21, 1984, to 105 °F (41 °C) on July 14, 1936.

See also

Map of Ohio State and its subdivision:- Adams

- Allen

- Ashland

- Ashtabula

- Athens

- Auglaize

- Belmont

- Brown

- Butler

- Carroll

- Champaign

- Clark

- Clermont

- Clinton

- Columbiana

- Coshocton

- Crawford

- Cuyahoga

- Darke

- Defiance

- Delaware

- Erie

- Fairfield

- Fayette

- Franklin

- Fulton

- Gallia

- Geauga

- Greene

- Guernsey

- Hamilton

- Hancock

- Hardin

- Harrison

- Henry

- Highland

- Hocking

- Holmes

- Huron

- Jackson

- Jefferson

- Knox

- Lake

- Lake Erie

- Lawrence

- Licking

- Logan

- Lorain

- Lucas

- Madison

- Mahoning

- Marion

- Medina

- Meigs

- Mercer

- Miami

- Monroe

- Montgomery

- Morgan

- Morrow

- Muskingum

- Noble

- Ottawa

- Paulding

- Perry

- Pickaway

- Pike

- Portage

- Preble

- Putnam

- Richland

- Ross

- Sandusky

- Scioto

- Seneca

- Shelby

- Stark

- Summit

- Trumbull

- Tuscarawas

- Union

- Van Wert

- Vinton

- Warren

- Washington

- Wayne

- Williams

- Wood

- Wyandot

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming