Milpitas (Spanish for ‘little milpas’) is a city in Santa Clara County, California, in Silicon Valley. As of the 2020 census, the city population was 80,273. The city’s origins lie in Rancho Milpitas, granted to Californio ranchero José María Alviso in 1835. Milpitas incorporated in 1954 and has become home to numerous high tech companies, as part of Silicon Valley.

| Name: | Milpitas city |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 25 |

| LSAD Description: | city (suffix) |

| State: | California |

| County: | Santa Clara County |

| Incorporated: | January 26, 1954 |

| Elevation: | 20 ft (6 m) |

| Total Area: | 13.52 sq mi (35.01 km²) |

| Land Area: | 13.48 sq mi (34.91 km²) |

| Water Area: | 0.04 sq mi (0.10 km²) 0.36% |

| Total Population: | 80,273 |

| Population Density: | 5,900/sq mi (2,300/km²) |

| ZIP code: | 95035, 95036 |

| Area code: | 408/669 |

| FIPS code: | 0647766 |

| Website: | www.milpitas.gov |

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

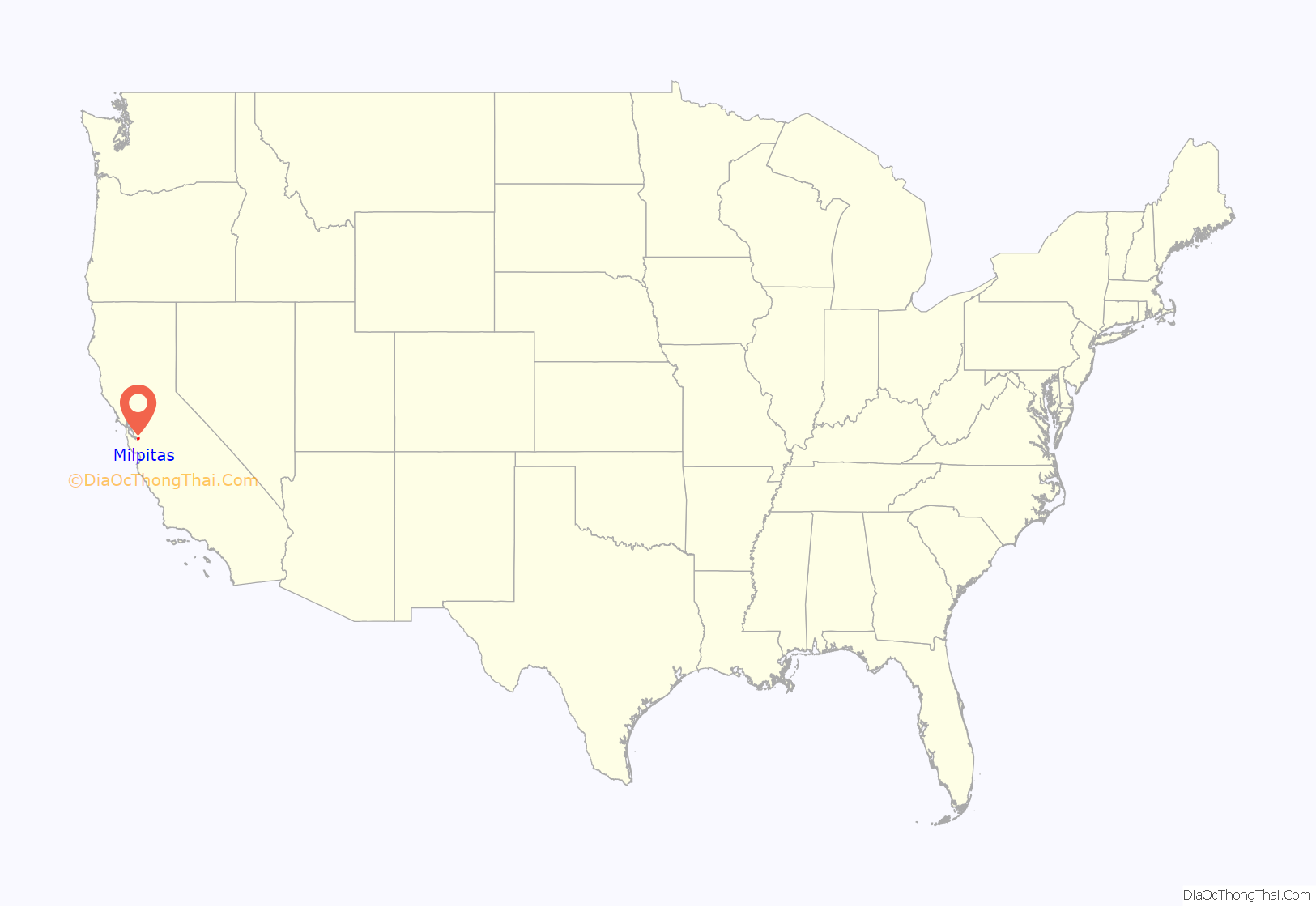

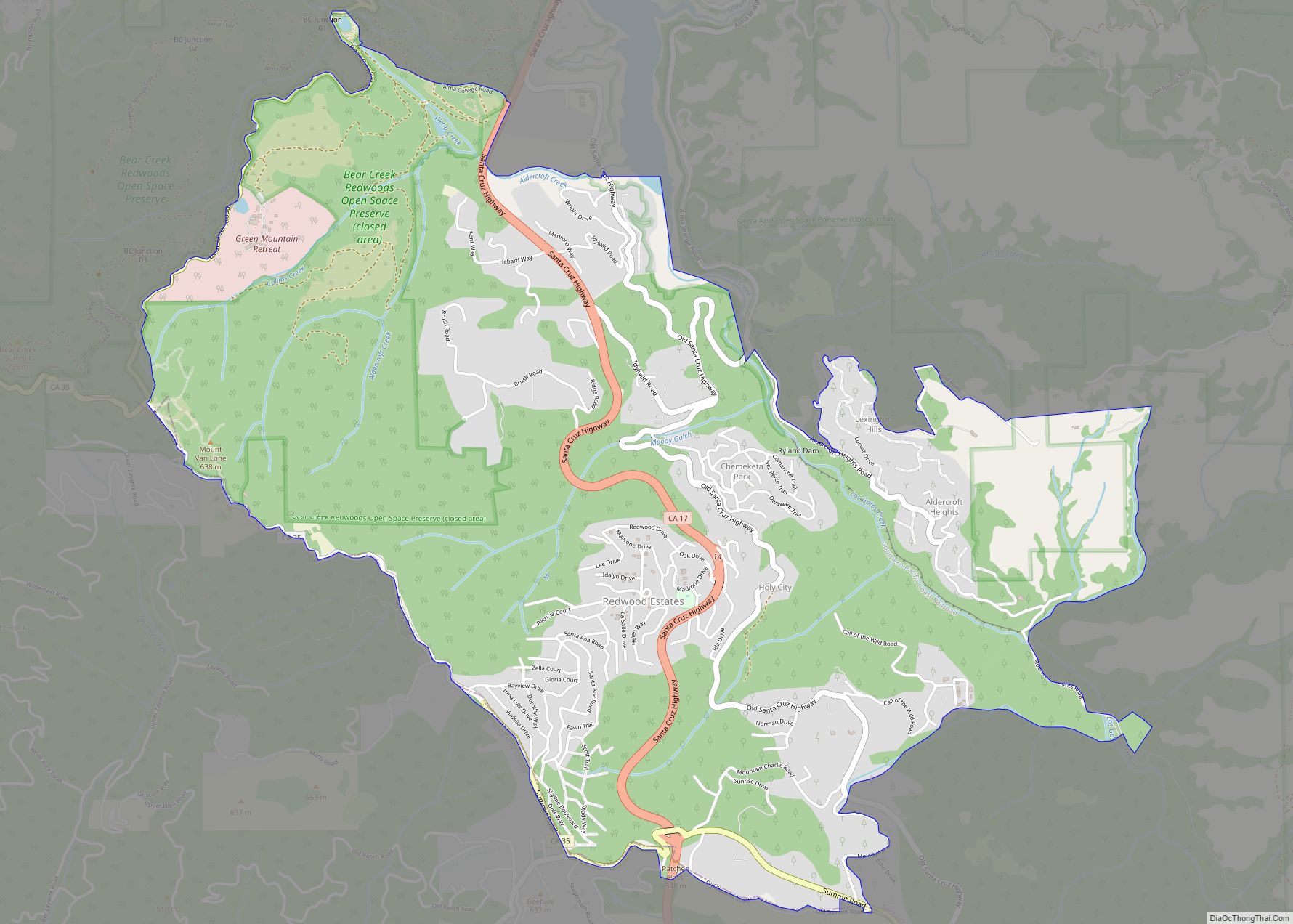

Milpitas location map. Where is Milpitas city?

History

Milpitas was first inhabited by Tamien people, a subgroup of the Ohlone people who had resided in the San Francisco Bay Area for thousands of years. The Ohlone Indians lived a traditional life based on everyday hunting and gathering. Some of the Ohlone lived in various villages within what is now Milpitas, including sites underneath what are now the Calvary Assembly of God Church and Higuera Adobe Park. Archaeological evidence gathered from Ohlone graves at the Elmwood Correctional Facility in 1993 revealed a rich trade with other tribes from Sacramento to Monterey.

During the Spanish expeditions of the late 18th century, several missions were founded in the San Francisco Bay Area. During the mission period, Milpitas served as a crossroads between Mission San José de Guadalupe in present-day Fremont and Mission Santa Clara de Asis in present-day Santa Clara. The land of modern-day Milpitas was divided between the 6,353-acre (25.71 km) Rancho Rincon de Los Esteros (Spanish for “corner of the wetlands”) granted to Ignacio Alviso; the 4,457.8-acre (18.040 km) Rancho Milpitas (Spanish for “little corn fields”) granted to José María Alviso; and the 4,394.35-acre (17.7833 km) Rancho Los Tularcitos (Spanish for “little tule marshes”) granted to José Higuera. Jose Maria Alviso was the son of Francisco Xavier Alviso and Maria Bojorquez, both of whom arrived in San Francisco as children with the de Anza Expedition. José María Alviso is considered to be the founder of Milpitas. Due to Jose Maria Alviso’s descendants’ difficulty securing his claims to the Rancho Milpitas property, portions of his land were either swindled from the Alviso family or were sold to American settlers to pay for legal fees.

Both landowners had built prominent adobe homes on their properties. Today, both adobes still exist and are the oldest structures in Milpitas. The seriously eroded walls of the Jose Higuera Adobe, now in Higuera Adobe Park, are encapsulated in a brick shell built c. 1970 by Marian Weller, a descendant of pioneer Joseph Weller.

The Alviso Adobe can be seen mostly in its original form, with one kitchen addition made by the Cuciz family after they purchased the adobe from the Gleason family in 1922. Prior to the city acquiring the Alviso Adobe in 1995, it was the oldest continuously occupied adobe house in California dating from the Mexican period and today is still gradually being restored and undergoing seismic upgrades by the City of Milpitas.

In the 1850s, large numbers of Americans of English, German, and Irish descent arrived to farm the fertile lands of Milpitas. The Burnett, Rose, Dempsey, Jacklin, Trimble, Ayer, Parks, Wool, Weller, Minnis, and Evans families are among the early settlers of Milpitas. (Today many schools, streets, and parks have been named in honor of these families.) These early settlers farmed the land that was once the ranchos. Some set up businesses on what was then called Mission Road (now called Main Street) between Calaveras Road (now called Carlo Street) and the Alviso-Milpitas Road (now called Serra Way). By the late 20th century this area became known as the “Midtown” district. Yet another influx of immigration came in the 1870s and 1880s as Portuguese sharecroppers from the Azores came to farm the Milpitas hillsides. Many of the Azoreans had such locally well-known surnames as Coelho, Covo, Mattos, Nunes, Spangler, Serpa, and Silva.

There is a local legend that in 1857, when the U.S. Postal Service wanted to locate a Post Office in Frederick Creighton’s store near the intersection of Mission Road and Alviso-Milpitas Road to serve the newly created Township, there was some support for naming it Penitencia, after the small Roman Catholic confessional building that had served local Indians and ranchers and had once stood several miles south of the village near Penitencia Creek which ran just west of the Mission Road. A local farmer and first Assistant Postmaster, Joseph Weller, felt the Spanish word Penitencia might be confused with the English word “penitentiary.” Instead of choosing Penitencia, he suggested another popular name for the area, Milpitas, after the name of Alviso’s property, Rancho Milpitas. Thus was born “Milpitas Township.”

For over a century, Milpitas served as a popular rest stop for travelers on the old Oakland−San Jose Highway. At the north side of the intersection of that road with the Milpitas-Alviso Road, for many years stood “French’s Hotel” that had been originally built by Alex Anderson prior to 1859, when Alfred French bought it from Austin M. Thompson. South of the site of French’s Hotel, was a saloon dating from at least 1856 when Agustus Rathbone purchased the land and “improvements” from Richard Greenham. The first murder in Milpitas was committed in the early 1860s in “Rathbone’s Saloon” (alas, the murderer escaped). Later the saloon was replaced by a hotel that is shown on the 1893 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map as “Goodwin’s Hotel” (perhaps the same Henry K. Goodwin who, in 1890, loaned money to prominent local rancher Marshall Pomeroy). Presumably, this hotel burned down and “Smith’s Corner,” which still stands, was built in 1895, by John Smith, as a saloon that served beer and wine to thirsty travelers for a century before becoming a restaurant in 2001. Around this central core, grocery and dry goods stores, blacksmithies, service stations, and, in the 1920s, one of America’s earliest “fast food” chain restaurants, “The Fat Boy”, opened nearby. Another of Milpitas’s most popular restaurants was the “Kozy Kitchen”, established in 1940 by the Carlo family in the former “Central Market” building. Kozy Kitchen was demolished soon after Jimmy Carlo sold the restaurant in 1999. Even in the early 1950s, Milpitas served a farming community of 800 people who walked a mere one or two blocks to work.

On January 26, 1954, faced with getting swallowed up by a rapidly expanding San Jose, Milpitas residents incorporated as a city that included the recently built Ford Auto Assembly plant. When San Jose attempted to annex Milpitas barely seven years later, the “Milpitas Minutemen” were quickly organized to oppose annexation and keep Milpitas independent. An overwhelming majority of Milpitas registered voters voted “No” to annexation in the 1961 election as a result of a vigorous anti-annexation campaign. Following the election, the anti-annexation committee, who had compared themselves to the Revolutionary War Minutemen who fought the British on Lexington Green—a role filled in this case by the neighboring city of San Jose—adopted the image of Daniel Chester French’s Minuteman statue, that stands near the site of the Old North Bridge in Concord, MA, as part of the official city seal. In the 1960s, the city approved the construction of the Calaveras overpass. Formerly at a junction with the Union Pacific railroad, Calaveras Boulevard had a bridge passing over six sets of railroad tracks after the construction was completed. Though the result was that local residents could now drive over the train tracks without waiting for a slow freight to pass, it resulted in the loss of the historical residential area. Here houses owned by city leaders had to be purchased by the city at full market value and either moved or demolished.

Starting in 1955, with the construction of the Ford Motor Assembly Plant, and accelerating in the 1960s and 1970s, extensive residential and retail development took place. Hayfields in Milpitas rapidly disappeared as industries and residential housing developments spread. Soon, the once rural town of Milpitas found itself a San Jose suburb. The population jumped from about 800 in 1950 to 62,698 in 2000. Several local farmers and businessmen who had chipped in from $2 to $50 to file for incorporation, had become millionaires within ten years. Most of them then moved away.

According to the book The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein (2017), when the Ford plant moved from Richmond to Milpitas in 1953, the town incorporated in order to pass laws that would exclude African American workers from residing there. “Union leaders met with Ford Executives and negotiated an agreement permitting all 1400 Richmond plant workers, including the approximately 250 African Americans, to transfer to the new facility. Once Ford’s plans became known, Milpitas residents incorporated the town and passed an emergency ordinance permitting the newly installed city council to ban apartment construction and allow only single family homes. … The Federal Housing Administration approved subdivision plans that met their specifications in Milpitas and guaranteed mortgages to qualified buyers … One of the specifications for mortgages insured in Milpitas (as in the rest of the country at that time) was an openly stated prohibition on sales to African Americans. Because Milpitas had no apartments, and houses in the area were off-limits to black workers-though their incomes and economic circumstances were like those of whites on the assembly line-African Americans had to choose between giving up the good industrial jobs, moving to apartments in a segregated neighborhood of San Jose, or enduring lengthy commutes between North Richmond and Milpitas.

In 1961, Ben F. Gross, a civil rights activist, became Milpitas’s first black city councilman with the backing of the UAW. This election was recognized nationally and received attention from Look and Life magazines. In 1966, Ben F. Gross became California’s first black mayor when he was elected by the city’s residents and “the only black mayor of a predominantly white town in California”. Mayor Gross was reelected in 1968 and continued fighting against Milpitas’s annexation by San Jose.

The Ford San Jose Assembly Plant closed in 1984, later being converted into a shopping mall, known as the Great Mall of the Bay Area, which opened in 1994.

In the early 21st century, the Milpitas light rail transit system station was added, making it the northeastern most light rail destination in the region. On January 26, 2004, the city celebrated the 50th anniversary of its incorporation and issued the book Milpitas: Five Dynamic Decades to commemorate 50 years of Milpitas’s history as a busy, exciting crossroads community.

Etymology

The name Milpitas is the plural diminutive of milpa, Mexican Spanish for “cornfield.” The name means “Place of little cornfields.” The word milpa is derived from the Nahuatl words milli, meaning “agricultural field,” and pan, meaning “on.”

The name Milpitas, perhaps used by Jose Maria Alviso to name his land grant, Rancho de las Milpitas, may have meant that there had been small Native American gardens nearby because of the rich alluvial soils of the area.

The first deed of property sale in Milpitas is found in the Santa Clara County Records General Index 1850–1856 (K-143) and is dated February 14, 1856. It is Juana Galindo Alviso, widow of Jose Maria Alviso, to Michael and Ellen Hughes for 800 acres (3.2 km) of land, today the Main Street area south of Carlo Street, although the deed gives the name of the Rancho as Rancho San Miguel, rather than as Milpitas.

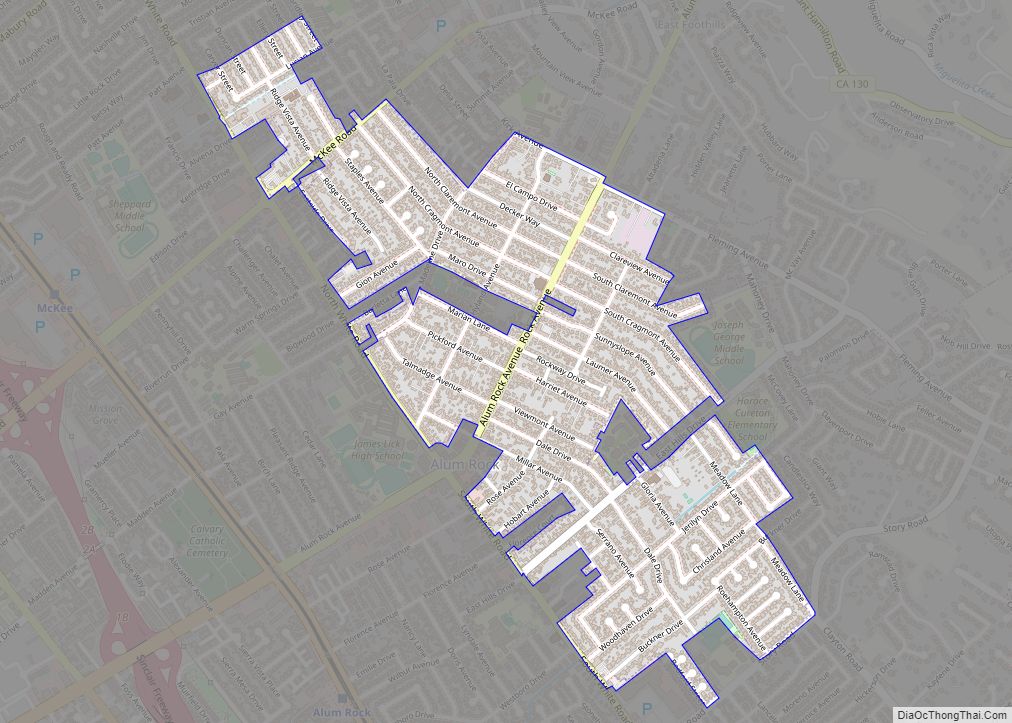

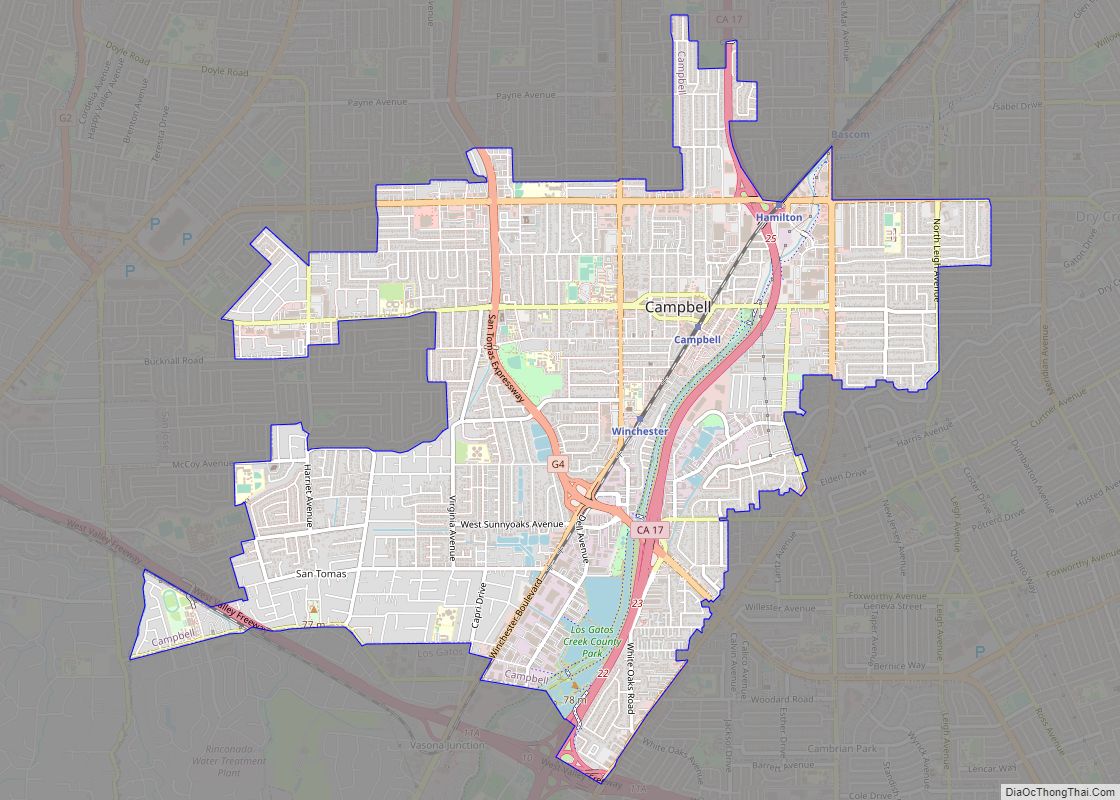

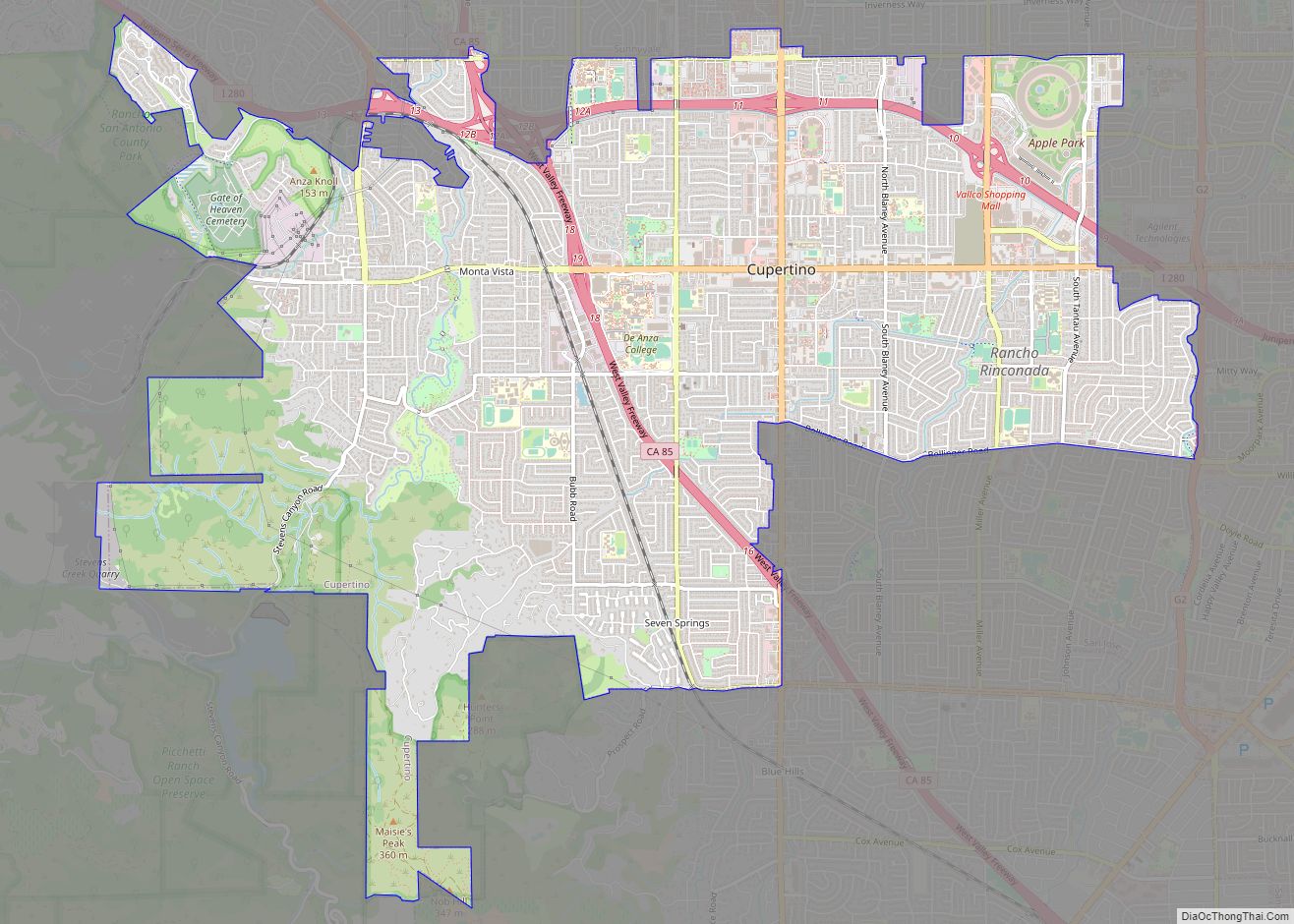

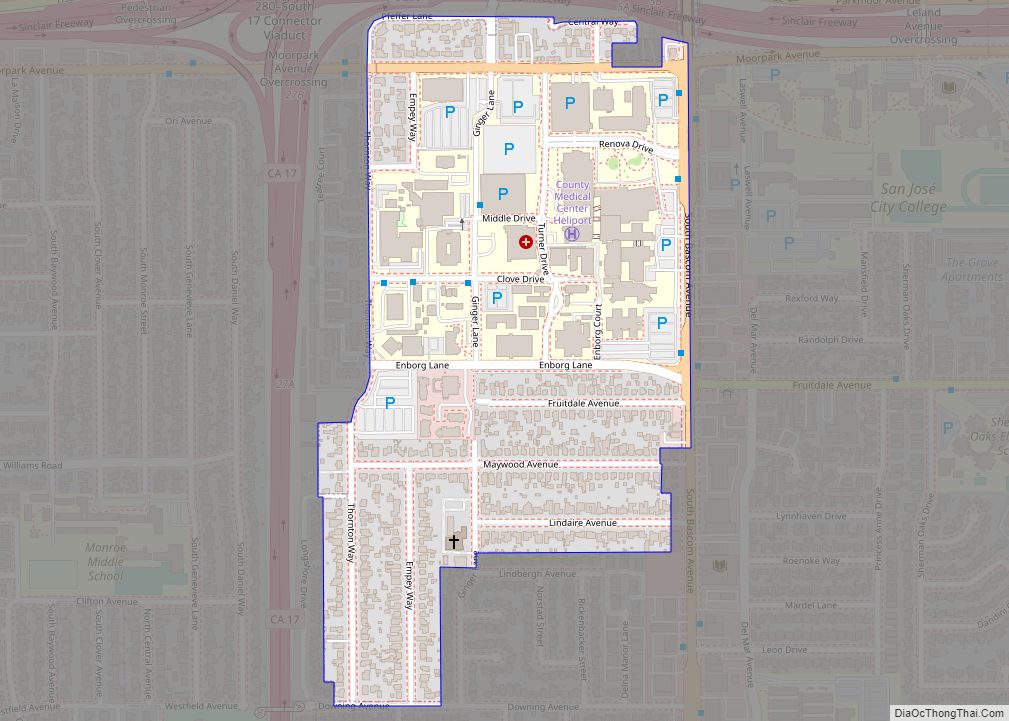

Milpitas Road Map

Milpitas city Satellite Map

Geography

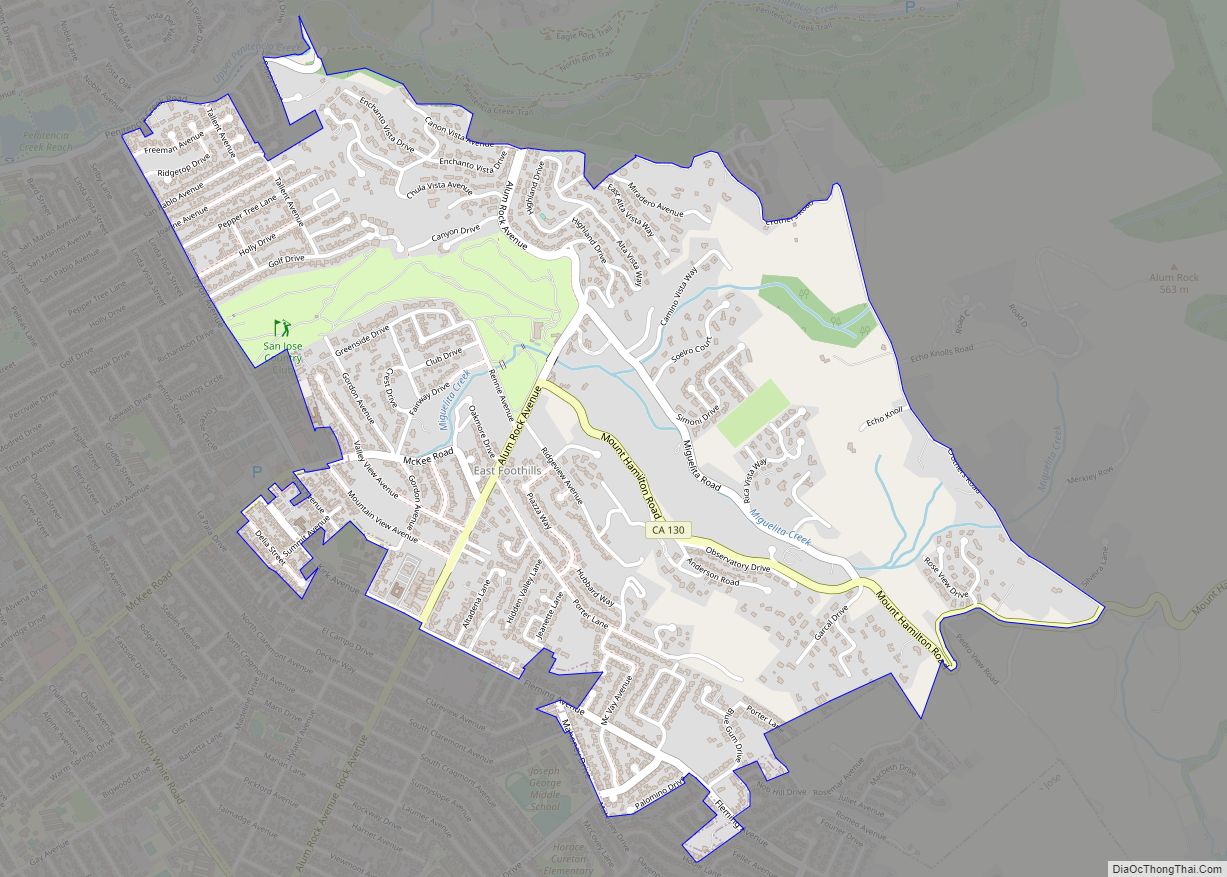

Milpitas lies in the northeastern corner of the Santa Clara Valley, which is south of San Francisco. Milpitas is generally considered to be a San Jose suburb in the South Bay, a term used to denote the southern part of the San Francisco Bay Area.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 13.6 sq mi (35.3 km). 13.6 sq mi (35.2 km) of it is land and 0.050 sq mi (0.13 km) of it (0.36%) is water.

The median elevation of Milpitas is 19 feet (6 m). At Piedmont Road, Evans Road, and North Park Victoria Drive, the elevation is generally about 100 feet (30 m), while the western area is almost at sea level. The highest point in Milpitas is a 1,289-foot (393 m) peak in the southeastern foothills.

To the east of Milpitas is a range of high foothills and mountains, part of the Diablo Range which runs along the east side of San Francisco Bay. Monument Peak is a prominent summit in the eastern Milpitas hills, and is the location of antenna broadcasting television stations KICU and KQEH to the San Francisco Bay Area.

There are also many creeks in Milpitas, most of which are part of the Berryessa Creek watershed. Calera Creek, Arroyo de los Coches, Penitencia Creek and Piedmont Creek are some of the creeks that flow from the Milpitas hills and empty into the San Francisco Bay. (See Berryessa Creek)

Urban layout

Milpitas is divided into three sections by Interstates 680 and 880. To the west of I-880 is a largely industrial and commercial area. Between I-880 and its eastern counterpart freeway, I-680, is an industrial zone in the south and residential neighborhoods in the north. Other residential neighborhoods and undeveloped mountains lie east of I-680.

In reality, Milpitas has no concentrated downtown “center,” but instead has several small retail centers generally located near residential developments and anchored by a supermarket. The so-called “Midtown” area, the oldest part of Milpitas, has few remaining historic residences and was the only commercial district that existed before 1945. Midtown is situated in the region where Main and Abel Streets run parallel to each other bordered by Montague Expressway in the south and Weller Street at the north end. A USPS post office, Saint John the Baptist Catholic Church, Elementary & Junior High Catholic School, the Milpitas Public Library (which incorporates the old Milpitas Grammar School building), the Smith/DeVries mansion, the Senior Center, and Elmwood Correctional Facility are all in the Midtown section of Milpitas. The Milpitas Civic Center, which includes City Hall, is not located in Midtown, but stands at the intersection of Milpitas and Calaveras Boulevards. The Civic Center is separated from Midtown by the Calaveras overpass. The boundaries that divide major Milpitas neighborhoods and districts include Calaveras Boulevard running from east to west and the Union Pacific railroad, which runs from north to south. The newest retail centers are west of Interstate 880.

Berryessa Creek flows through Milpitas.

Pollution

Milpitas occasionally experiences odorous air traveling downwind from bay salt marshes, from the Newby Island landfill, from the anaerobic digestion facility at Zero Waste Energy Development Company, and from the San Jose sewage treatment plant’s percolation ponds. Most malodorous during the autumn, it is especially pungent west of Interstate 880 because of its close location to the San Francisco Bay and the direction of the prevailing winds out of the north-northwest. The City of Milpitas would like to remedy this air quality problem to the extent it can and encourages its residents to file odor complaints.

Local creeks and the nearby San Francisco Bay suffer somewhat from water pollution originating from street water runoff and industrial wastes. The creeks in Milpitas, especially Calera, Scott, and Berryessa Creeks, used to be prime fishing spots for native steelhead until pollutants from urban development and industry killed the fish starting in the 1950s. While small populations of steelhead and even salmon still may be seen in area streams these cannot legally be fished and consumption of legal catches is limited by mercury contamination.

The I-880 corridor has experienced relatively elevated levels of air pollution from freeway traffic. For example, eight-hour standards for carbon monoxide have been near to maximum levels for the last two decades.

Climate

Set within a warm Mediterranean climate zone in Santa Clara County, Milpitas enjoys warm, sunny weather with few extreme temperatures. Rainfall is confined mostly to the winter months. During winter, temperatures are relatively cold, at an average of 41 to 59 °F (5 to 15 °C). Showers and cloudy days come and go during this season, dropping most of the city’s annual 15 inches (380 mm) of precipitation, and as spring approaches, the gentle rains gradually dwindle. In summer, the grasslands on the hillsides dehydrate rapidly and form bright, golden sheets on the mountains set off by stands of oak. Summer is dry and warm but not hot like in other parts the Bay Area. Temperatures infrequently reach over 100 °F (38 °C), with most days in the low 80s to the mid 80s. From June to September, Milpitas experiences little rain, and as autumn approaches, the weather gradually cools down. Many temperate-climate trees drop their leaves during fall in the South Bay but the winter temperature is warm enough for evergreens like palm trees to thrive.

See also

Map of California State and its subdivision:- Alameda

- Alpine

- Amador

- Butte

- Calaveras

- Colusa

- Contra Costa

- Del Norte

- El Dorado

- Fresno

- Glenn

- Humboldt

- Imperial

- Inyo

- Kern

- Kings

- Lake

- Lassen

- Los Angeles

- Madera

- Marin

- Mariposa

- Mendocino

- Merced

- Modoc

- Mono

- Monterey

- Napa

- Nevada

- Orange

- Placer

- Plumas

- Riverside

- Sacramento

- San Benito

- San Bernardino

- San Diego

- San Francisco

- San Joaquin

- San Luis Obispo

- San Mateo

- Santa Barbara

- Santa Clara

- Santa Cruz

- Shasta

- Sierra

- Siskiyou

- Solano

- Sonoma

- Stanislaus

- Sutter

- Tehama

- Trinity

- Tulare

- Tuolumne

- Ventura

- Yolo

- Yuba

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming