Norvelt is a census-designated place in Mount Pleasant Township, Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, United States, founded in 1934 as Westmoreland Homesteads. In 1937 it was renamed to honor Eleanor Roosevelt. The community was part of the Calumet-Norvelt CDP for the 2000 census, but was split into the two separate communities of Calumet and Norvelt for the 2010 census. Calumet was a typical company town, locally referred to as a “patch” or “patch town”, built by a single company to house coal miners as cheaply as possible. On the other hand, Norvelt was created during the Great Depression by the federal government of the United States as a model community, intended to increase the standard of living of laid-off coal miners. Award winning writer Jack Gantos was born in the village and wrote two books about it

| Name: | Norvelt CDP |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 57 |

| LSAD Description: | CDP (suffix) |

| State: | Pennsylvania |

| County: | Westmoreland County |

| Founded: | 1934 |

| Elevation: | 1,010 ft (310 m) |

| Total Area: | 1.79 sq mi (4.64 km²) |

| Land Area: | 1.79 sq mi (4.64 km²) |

| Water Area: | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km²) |

| Total Population: | 846 |

| Population Density: | 472.10/sq mi (182.28/km²) |

| ZIP code: | 15674 (Norvelt) |

| Area code: | Area code 724 |

| FIPS code: | 4255616 |

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

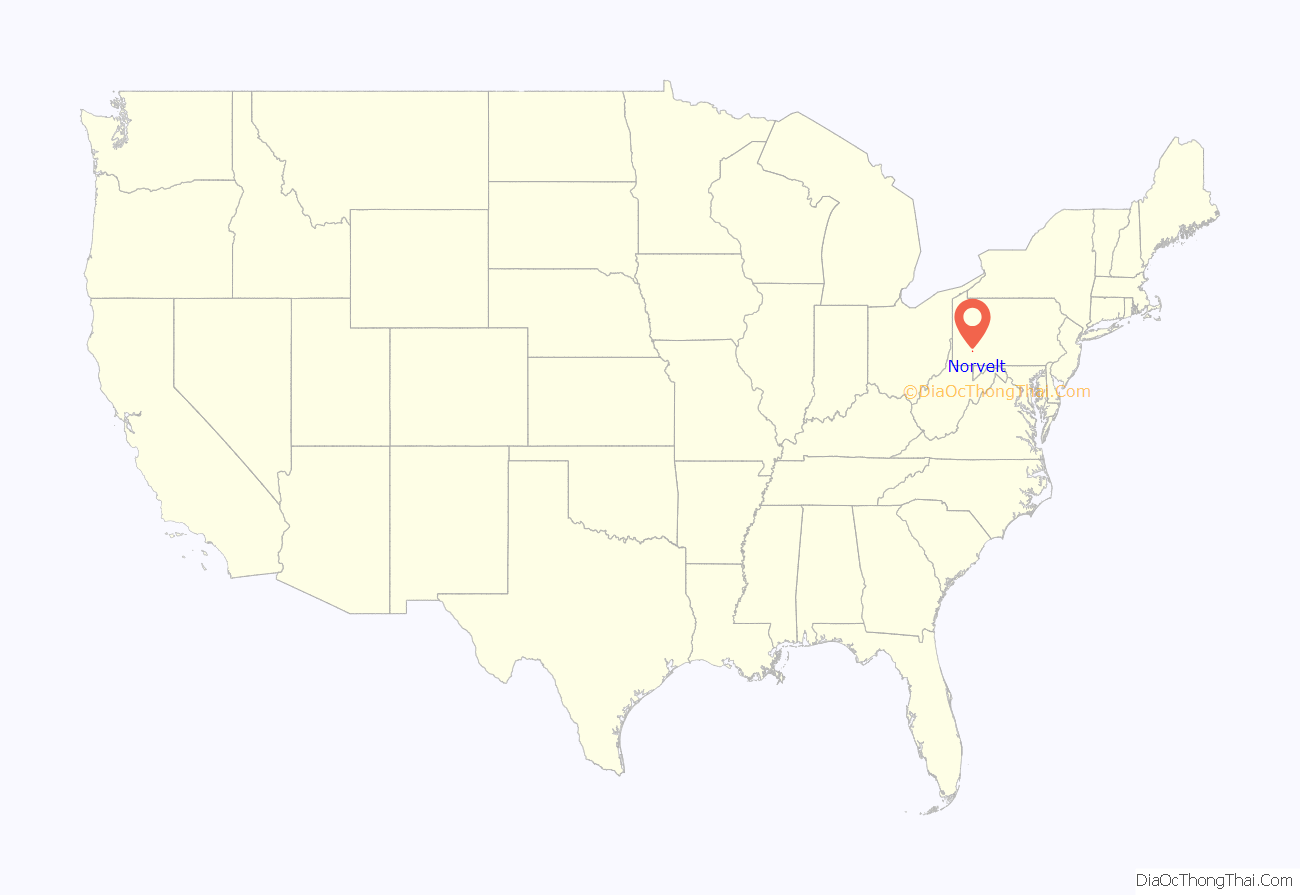

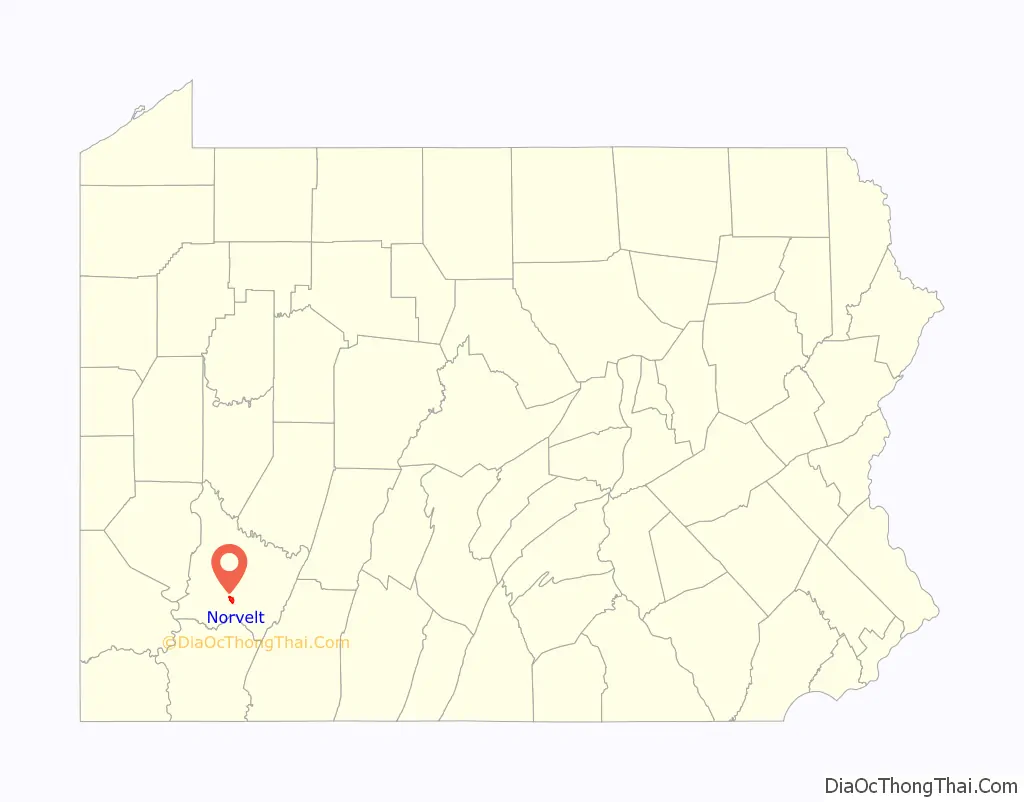

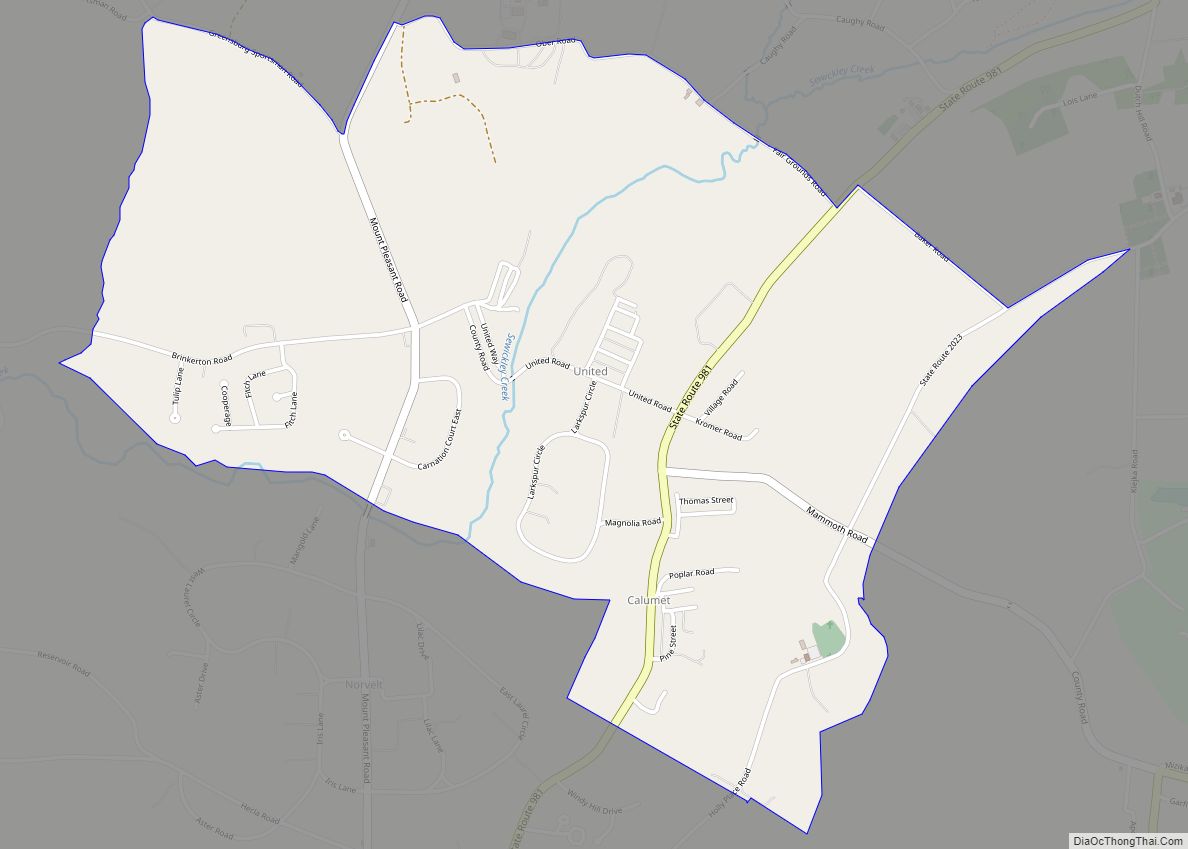

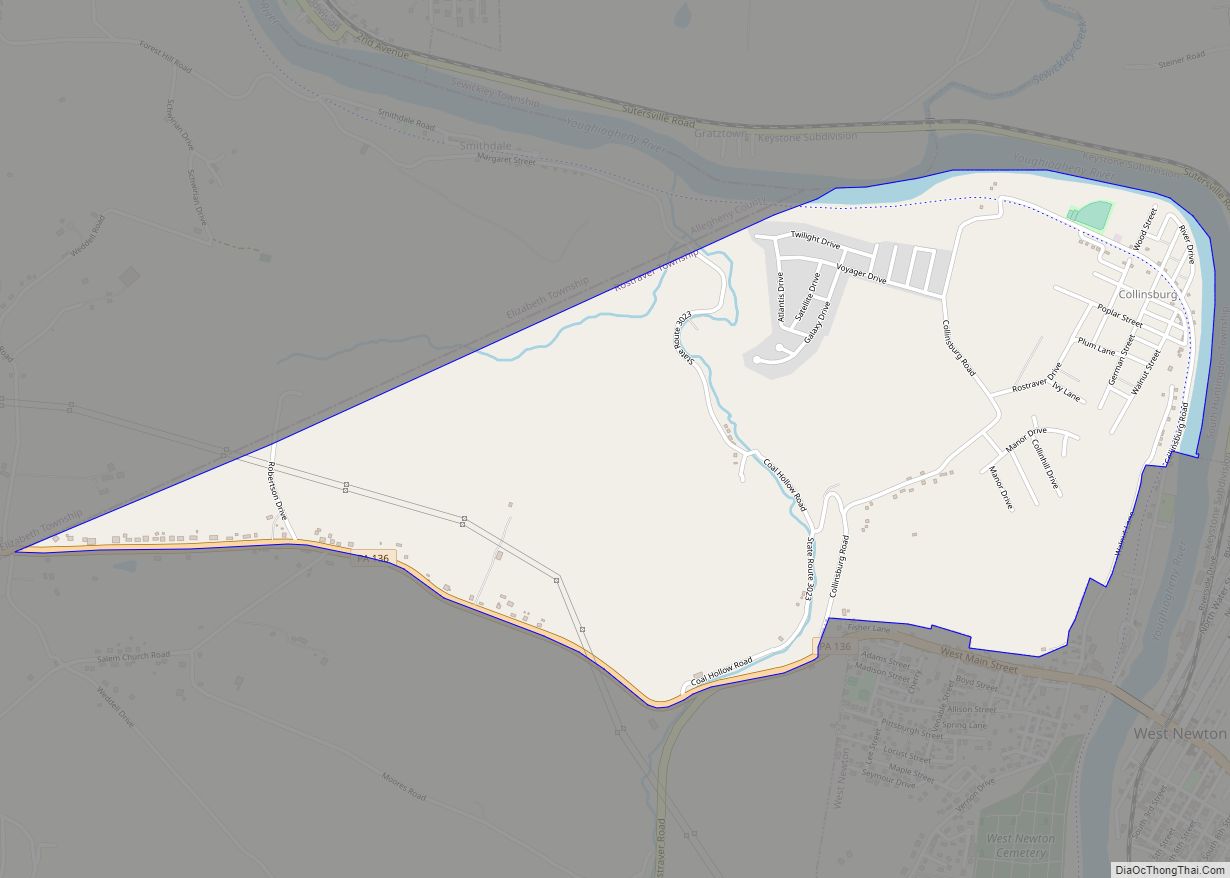

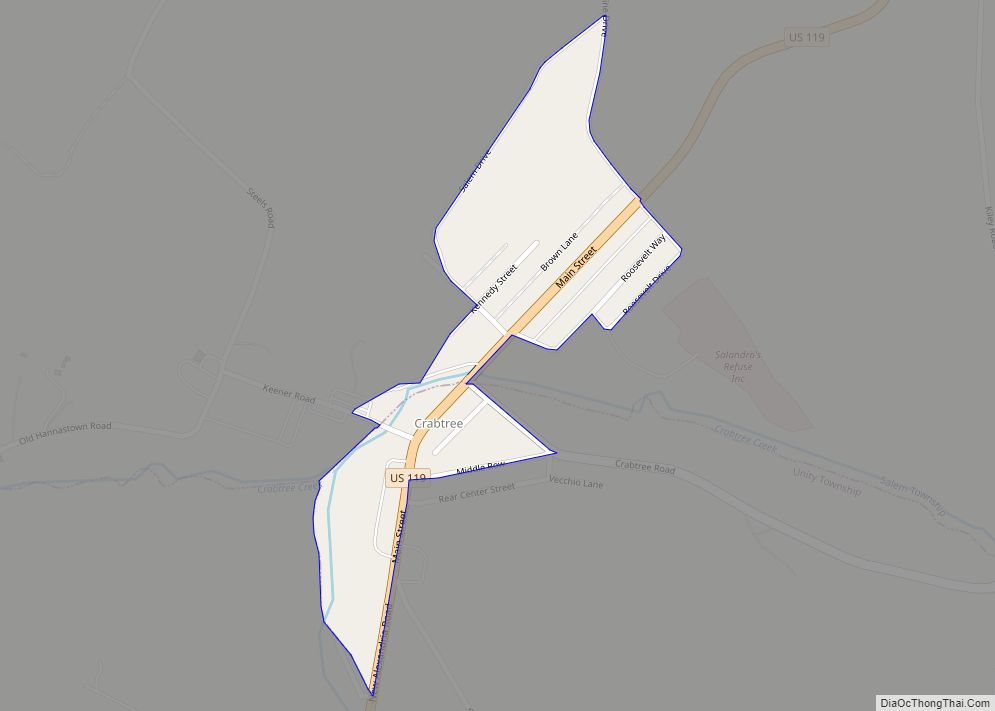

Norvelt location map. Where is Norvelt CDP?

History

Background

As part of the sweeping National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 (NIRA), Congress allocated $25 million for the creation of “subsistence homesteads” for dislocated industrial workers. Over the course of the program’s eleven-year history, the federal government seeded nearly 100 planned, cooperative communities. Norvelt, in southwestern Pennsylvania, was the fourth. The idea for the program was a throwback to the Jeffersonian ideal of a back-to-the-land movement, popularized by Americans who promoted small-scale subsistence farming as an antidote to economic exploitation and the alienation of modern life. The idea gained strength in the 1920s among a wide variety of progressive organizations, including church-related groups such as the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) which was the social services arm of the Quakers. During the 1920s, the AFSC had become deeply concerned with the violence that resulted from labor strife, particularly in the bituminous coal fields of Appalachia. So AFSC volunteers traveled to the bituminous-coal regions in West Virginia and Pennsylvania to help the families of striking and unemployed coal miners. The AFSC also believed in the necessity of economic and social justice as a means of insuring lasting peace in this section of the United States. To that end, it clothed and fed the families of unemployed miners during strikes, and later launched subsistence gardening and vocational retraining programs. After the onset of the Great Depression, these experiences placed the AFSC in the forefront of the movement for cooperative communities, so much so that the United States Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes recruited AFSC staff to guide its subsistence homesteads program.

The Great Depression was an opportunity to implement these ideals. Supporters lobbied for creating a government-sponsored resettlement program that would place unemployed industrial workers in farmstead communities. Promoted as a relief measure, it quickly became weighted with the much more ambitious goal of cooperative living. In 1934, Interior Secretary Ickes named Milburn Wilson to head the newly created “Division of Subsistence Homesteads”. Wilson, in turn, selected the AFSC’s Clarence Pickett to help administer the program. As the AFSC’s executive secretary, Pickett already had overseen vocational reeducation and cooperative farm programs for unemployed coal miners in West Virginia. The AFSC’s work supplied the prototype for the federal program. In the years that followed, AFSC lent its support to the federal program and later sponsored its own cooperative community, Penn-Craft in Fayette County.

Although the government opened its program to broad segments of the unemployed, the division was especially keen on it reaching bituminous coal miners. Geographically isolated and dominated by a single employer, the residents of most patch towns were especially vulnerable once employment evaporated. So the division designed the homestead program to give miners and their families an opportunity to become economically independent by working the land, which, in theory, would also free them from the boom/bust cycle of industrial capitalism. Once the division had identified its target populations, the federal government began buying large parcels of land for subdivision into individual homesteads for up to 300 families. Encouraging home ownership through a rent-to-own program, the program’s administrators expected residents to grow or raise everything they needed to survive, but they also hoped that the new communities would lure local industries that would in turn provide jobs and needed income.

Although the project faced few political hurdles, the design of the houses for Norvelt and other subsistence farmstead communities set off a debate that revealed top government officials’ contrasting ambitions for the program. Both President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Interior Secretary Ickes believed that the houses should be constructed to minimal standards, without electricity and running water, as befit a relief program. But program director Milburn Wilson and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt insisted that the homes be furnished with plumbing, electric lights, and other modern conveniences. Senator Harry F. Byrd, a Democrat from Virginia, criticized such features as an “extravagance” for “simple mountain folk,” but Wilson and the First Lady prevailed. Both argued that the project, as a demonstration project, should afford its residents with homes that would elevate their standard of living.

Building Norvelt

In April 1934, federal officials acquired 1,326 acres (5.37 km) of farmland in Mount Pleasant Township, and announced construction of the Westmoreland Homesteads. Following Division guidelines, local architect Paul Bartholomew designed the planned community’s buildings and its overall layout. On 772 acres (3.12 km) he arranged 254 individual lots, ranging in size from 1.7 to 7 acres (28,000 m), in six, mostly curvilinear sections. Each lot was to feature a simply designed, 1+1⁄2-story Cape Cod. Originally, the houses were available in 4- to 6-room models, with a living room, eat-in kitchen, utility room, bathroom and bedroom space. Utilities included water and electricity. The remaining 728 acres (2.95 km) Bartholomew reserved for a cooperative farm, a schoolhouse, playground, post office, and other common buildings. These original depression-era Cape Cod–style homes are called “Norvelt Houses” by the locals. A six-room house on more than 2 acres (8,100 m) sold for $2131.28, a price that reflected annual mortgage payments of $212.50, which was one-fourth of the prospective purchasers’ estimated annual cash income of $850, and a 40-year mortgage at 3% interest. Over 1,850 applied for the government properties, which spanned nearly 1,500 acres. Two hundred and fifty four families received houses.

Pickett helped establish the first American Friends Service Committee work camp in, what would become Norvelt, to help the Homesteads project with the construction of a reservoir and ditch to hold a water main for the community. In the summer of 1934, 55 young volunteers contributed 10,000 hours at Norvelt by digging a ditch one-and-a-half miles long and constructing a 260,000-gallon reservoir. The directors of this work camp were Mildred and Wilmer Young, who later led several experiments with cooperative enterprises in Mississippi and South Carolina. The first 1,200 residents were broadly representative of the region’s ethnic and racial diversity. As they arrived, heads of households were put to work building the houses they would later occupy.

Three years later, Westmoreland Homesteads was the largest of President Roosevelt’s 92 model subsistence homesteads that provided relief for displaced miners and industrial workers.

Basically the government purchased the land and people built their own homes on a lease-to-purchase agreement. Families rented their homes from the government for $12 to $14 a month, which was applied to the future purchase price of the house. By 1946, all the renters had purchased their homes. These early homes had everything a family would need to survive. These amenities included a grape arbor, 3-4 acres of land to plant a garden, and chicken coops. To make construction as efficient and cost-effective as possible, the division assigned crews to a single, specific construction task, such as digging the foundation or installing flooring—thus anticipating the mass building methods that would characterize large-scale residential developments such as Levittown after World War II—and applied most of workers’ wages directly to the cost of their homesteads. After a resident’s home was built, the government then provided each family with a wheelbarrow, rake, hoe and shovel. Mounds of earth were then dumped in front of the houses, and the tenants prepared their own lawns. Families were also expected to paint their own homes. Their choices of paint were white, gray or yellow. In May 1935, the first families began moving into Westmoreland Homesteads, and the task of creating a community began. Under the direction of a community manager, homesteaders established garden plots and raised livestock, including hogs and chickens. Some families produced enough to sell their surplus at a market, but for most, subsistence farming failed to meet their needs. To remedy the situation, in 1939, administrators at the Division, now under the “Rural Resettlement Administration”, approved a loan for the construction of a small garment factory on site. Administered by the “Cooperative Association”, a non-profit entity which also operated a cooperative store and a community health center, the garment factory by 1940 employed around 150 men and women.

Eleanor Roosevelt’s visit and legacy

On May 21, 1937, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited Westmoreland Homesteads to mark the arrival of the community’s final homesteader. Accompanying her on the trip was the wife of United States Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr. “I am no believer in paternalism. I do not like charities,” she had said earlier. But cooperative communities such as Westmoreland Homesteads, she went on, offered an alternative to “our rather settled ideas” that could “provide equality of opportunity for all and prevent the recurrence of a similar disaster [depression] in the future.” Residents were so taken by the First Lady’s personal expression of interest in the program that they promptly agreed to rename the community in her honor. (The new town name, Norvelt, was a combination of the last syllables in her names: EleaNOR RooseVELT.)

Support from many high-level politicians helped Norvelt survive until 1944, when the federal government disbanded the homestead program and dispersed its assets. Most residents had by this time managed to purchase their homes and property. By 1950, the cooperative store and farm had shut down, but the garment factory, under private ownership of AMCO of Norvelt, continued for many years. The garment factory, on Mount Pleasant Road in Norvelt, is owned and operated by Union Apparel Incorporated, which manufactures and exports men’s and boy’s tailored dress and sport coats as well as women’s, misses’ and juniors’ suits and coats.

Norvelt was born out of the socialist idea of community farming and of a need to eliminate the strains of capitalism. However, it wasn’t long before many in the community abandoned working on the cooperative farms in exchange for higher paying jobs in the private sector. Residents took up jobs in neighboring Latrobe, Greensburg and Mount Pleasant.

Norvelt never achieved the lofty goals that Eleanor Roosevelt and others had invested in it. As a relief measure, however, it was a success. In 2002, Norvelt’s handful of surviving original pioneers expressed their appreciation for their town during the festivities for the historic marker designation. Evidence of the town’s original name is still visible. The village’s laundromat still carries the name Homestead. The entrance to Roosevelt Hall reads Westmoreland Homestead’s “Norvelt” Volunteer Fire Department.

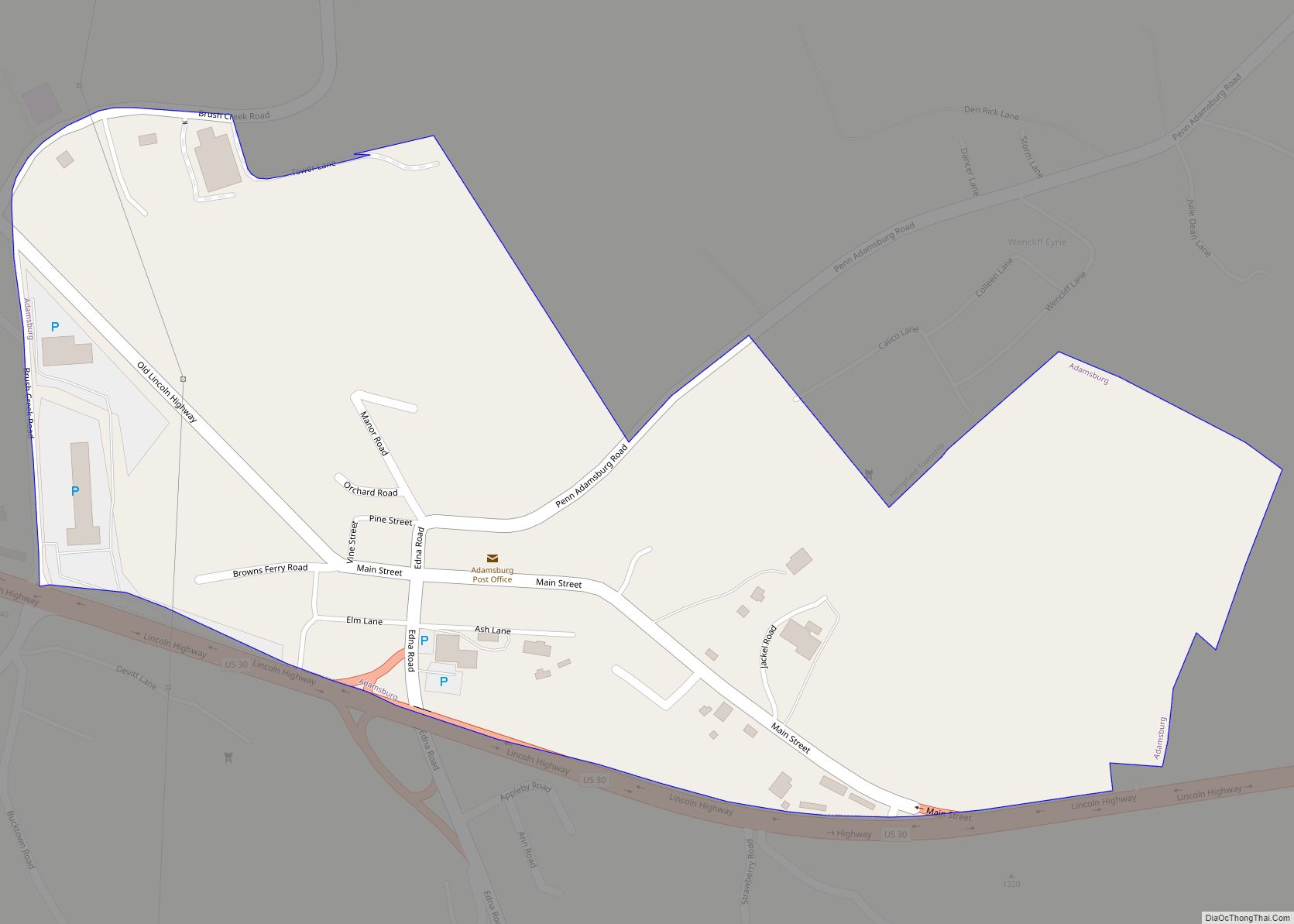

Norvelt Road Map

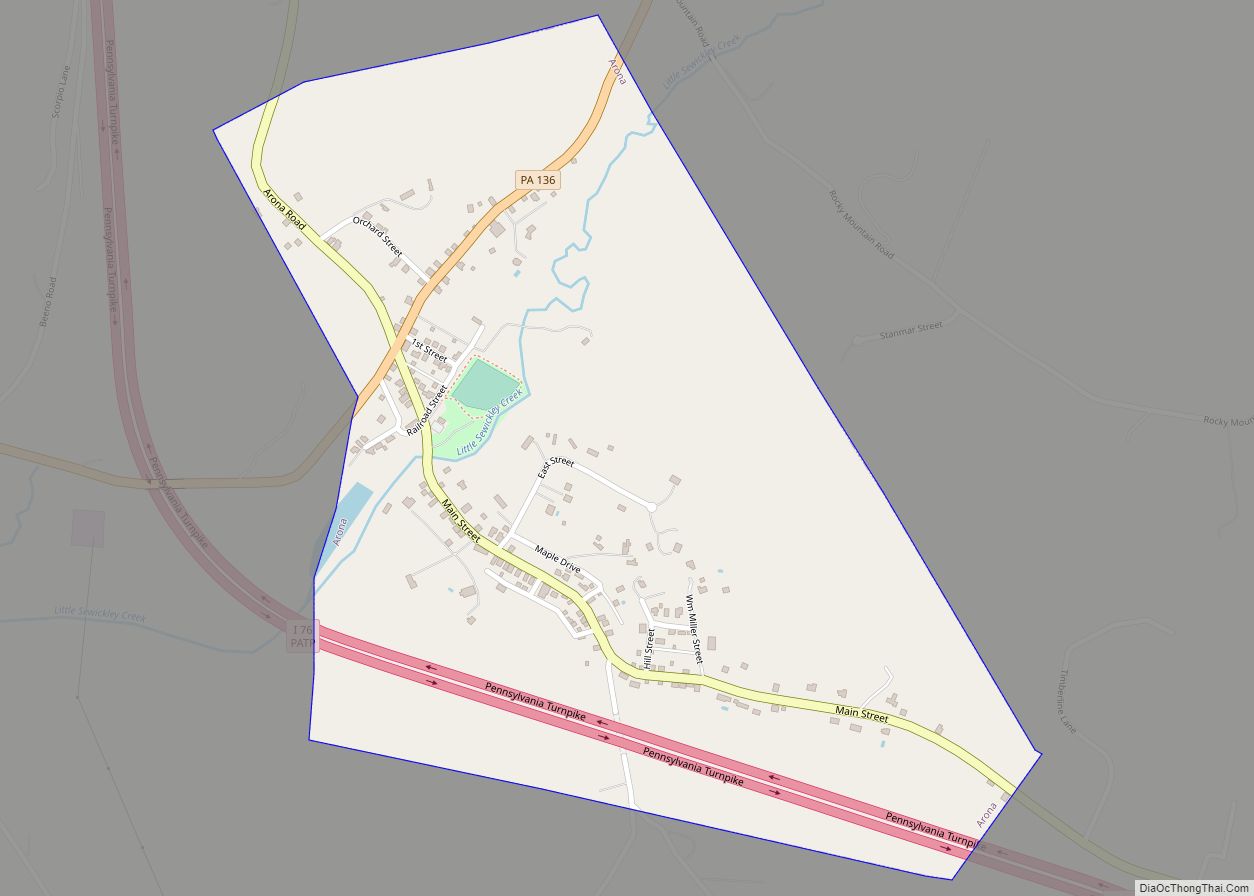

Norvelt city Satellite Map

Geography

Sections

The two main areas of Norvelt are “A” section and “B” section, connected into one 2-mile (3.2 km) loose circle made up of East Laurel Circle and West Laurel Circle running on either side of Mt. Pleasant Road. Both circles are built into the rolling hills, and the tree-lined roads.

Waterways

Norvelt has many small waterways. The largest is Sewickley Creek. The Sewickley stretches through Mammoth, Trauger, Calumet, and Norvelt. The Sewickley Creek Watershed Association, a non-profit organization monitors recommends and implements actions essential to the conservation of the Sewickley Creek watershed area for recreational purposes.

Norvelt also has many smaller creeks, most running through it. The small creeks are lined with stone blocks, and run parallel to the village’s circular streets and through the yards.

See also

Map of Pennsylvania State and its subdivision:- Adams

- Allegheny

- Armstrong

- Beaver

- Bedford

- Berks

- Blair

- Bradford

- Bucks

- Butler

- Cambria

- Cameron

- Carbon

- Centre

- Chester

- Clarion

- Clearfield

- Clinton

- Columbia

- Crawford

- Cumberland

- Dauphin

- Delaware

- Elk

- Erie

- Fayette

- Forest

- Franklin

- Fulton

- Greene

- Huntingdon

- Indiana

- Jefferson

- Juniata

- Lackawanna

- Lancaster

- Lawrence

- Lebanon

- Lehigh

- Luzerne

- Lycoming

- Mc Kean

- Mercer

- Mifflin

- Monroe

- Montgomery

- Montour

- Northampton

- Northumberland

- Perry

- Philadelphia

- Pike

- Potter

- Schuylkill

- Snyder

- Somerset

- Sullivan

- Susquehanna

- Tioga

- Union

- Venango

- Warren

- Washington

- Wayne

- Westmoreland

- Wyoming

- York

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming