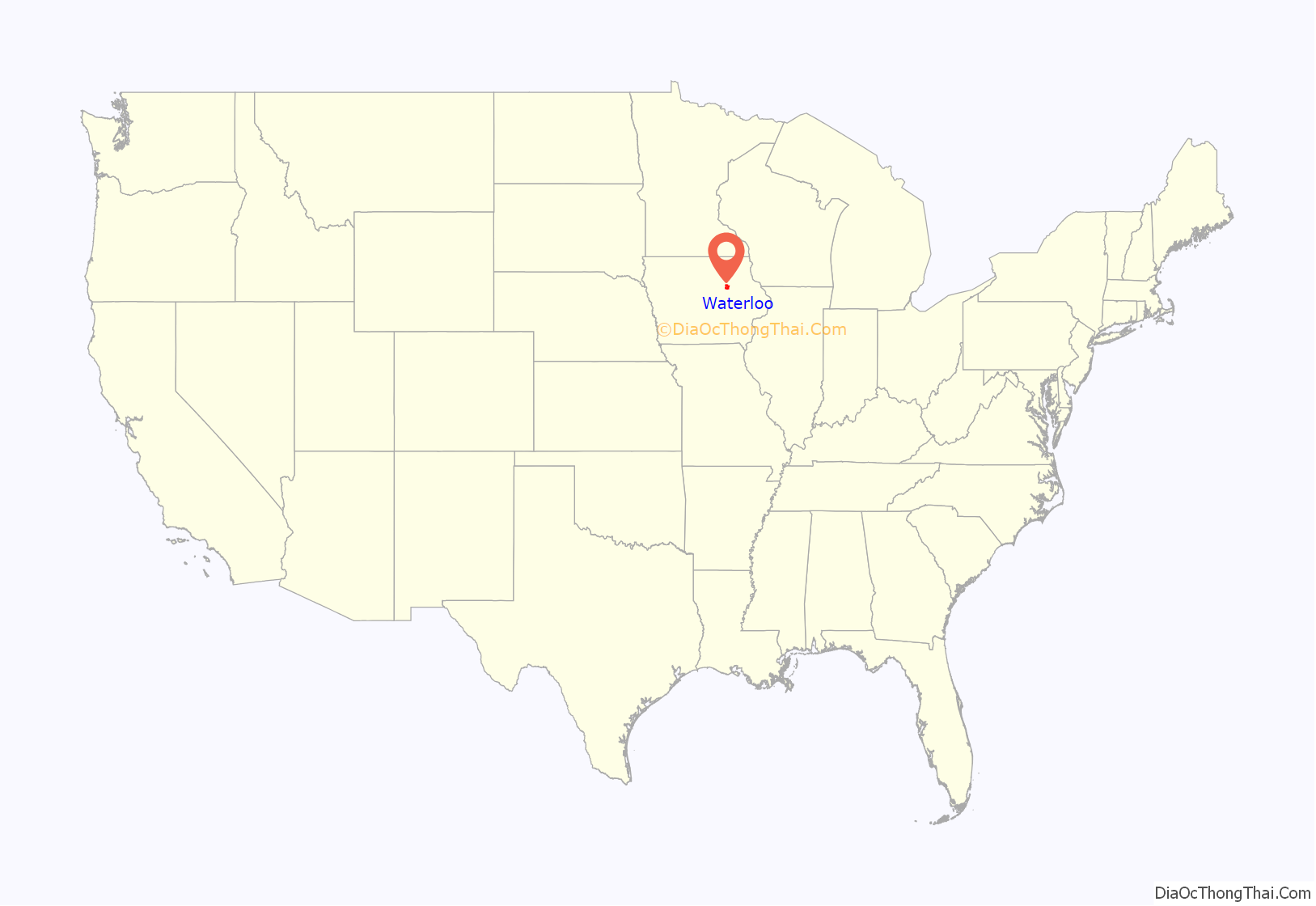

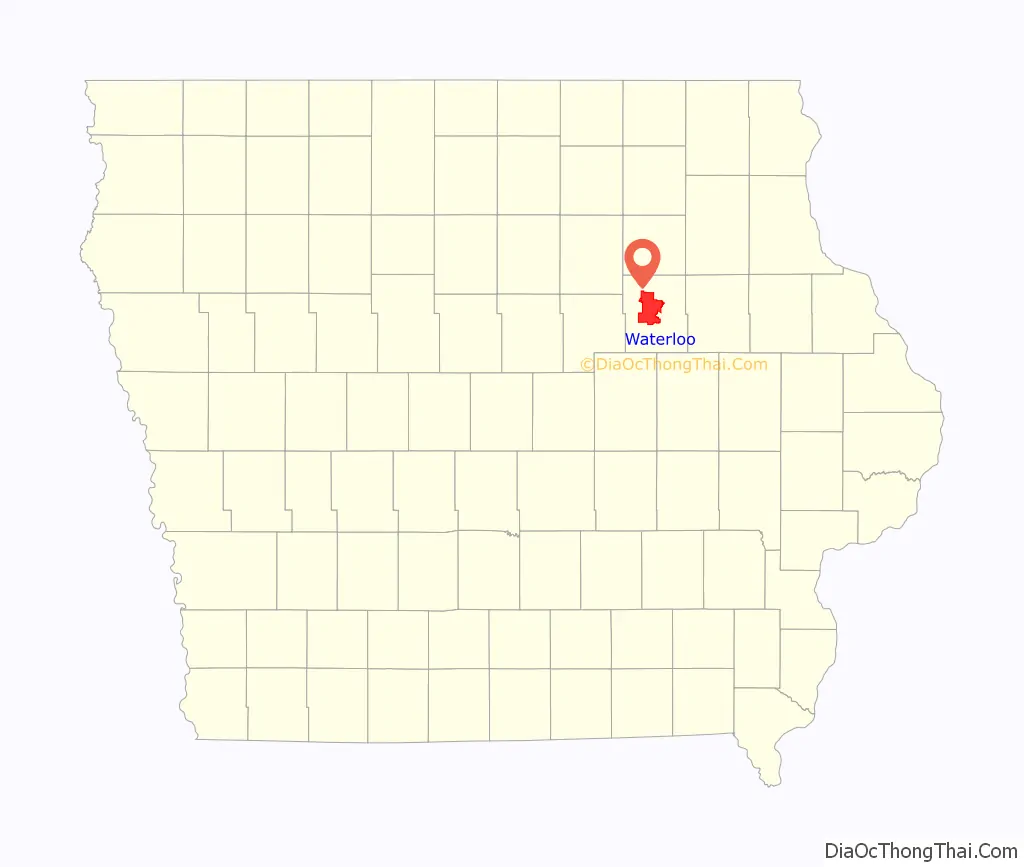

Waterloo is a city in and the county seat of Black Hawk County, Iowa, United States. As of the 2020 United States Census the population was 67,314, making it the eighth-largest city in the state. The city is part of the Waterloo – Cedar Falls Metropolitan Statistical Area, and is the more populous of the two cities.

| Name: | Waterloo city |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 25 |

| LSAD Description: | city (suffix) |

| State: | Iowa |

| County: | Black Hawk County |

| Incorporated: | 1868 |

| Elevation: | 883 ft (269 m) |

| Land Area: | 61.59 sq mi (159.53 km²) |

| Water Area: | 1.84 sq mi (4.76 km²) |

| Population Density: | 1,092.85/sq mi (421.95/km²) |

| ZIP code: | 50701-50707 |

| Area code: | 319 |

| FIPS code: | 1982425 |

| Website: | cityofwaterlooiowa.com |

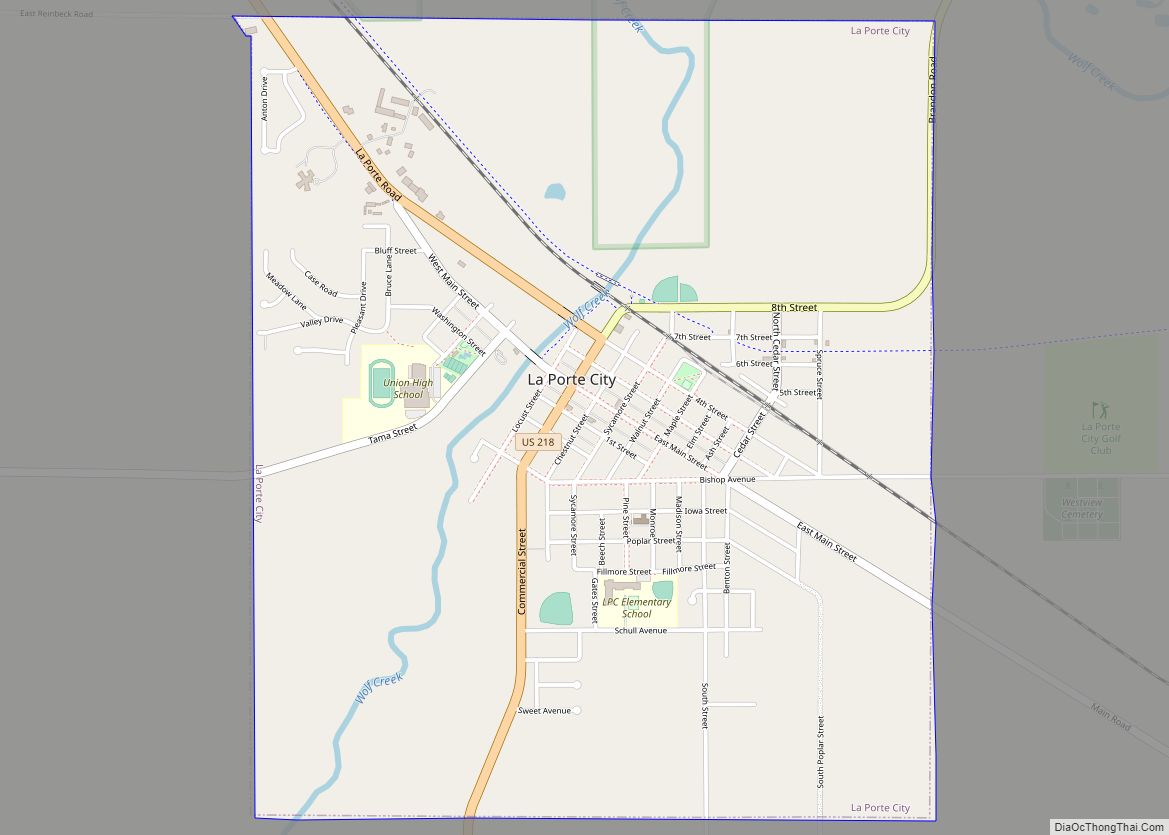

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

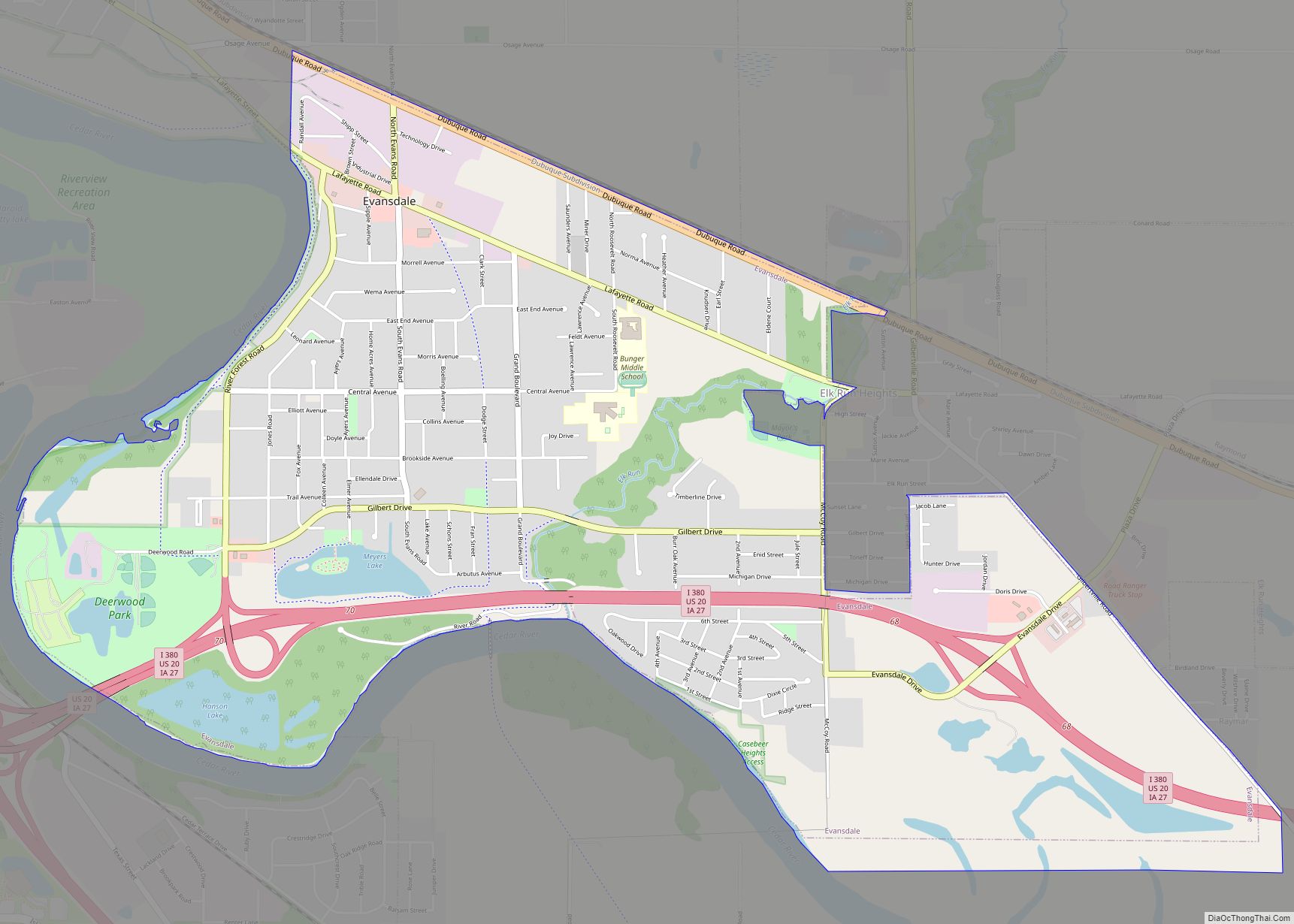

Waterloo location map. Where is Waterloo city?

History

Waterloo was originally known as Prairie Rapids Crossing. The town was established near two Meskwaki American tribal seasonal camps alongside the Cedar River. It was first settled in 1845 when George and Mary Melrose Hanna and their children arrived on the east bank of the Red Cedar River (now just called the Cedar River). They were followed by the Virden and Mullan families in 1846. Evidence of these earliest families can still be found in the street names Hanna Boulevard, Mullan Avenue and Virden Creek.

On December 8, 1845, the Iowa State Register and Waterloo Herald was the first newspaper published in Waterloo.

The name Waterloo supplanted the original name, Prairie Rapids Crossing, shortly after Charles Mullan petitioned for a post office in the town. Since the signed petition did not include the name of the proposed post office location, Mullan was charged with selecting the name when he submitted the petition. Tradition has it that as he flipped through a list of other post offices in the United States, he came upon the name Waterloo. The name struck his fancy, and a post office was established under that name. There were two extended periods of rapid growth over the next 115 years. From 1895 to 1915, the population increased from 8,490 to 33,097, a 290% increase. From 1925 to 1960, population increased from 36,771 to 71,755. The 1895 to 1915 period was a time of rapid growth in manufacturing, rail transportation and wholesale operations. During this period the Waterloo Gasoline Traction Engine Company moved to Waterloo and, shortly after, the Rath Packing Company moved from Dubuque. Another major employer throughout the first two-thirds of the 20th century was the Illinois Central Railroad. Among the others was the less-successful brass era automobile manufacturer, the Maytag-Mason Motor Company.

On June 7, 1934, bank robber Tommy Carroll had a shootout with the FBI when he and his wife stopped to pick up gas. Accidentally parking next to a police car and wasting time dropping his gun and picking it back up, Carroll was forced to flee into an alley, where he was shot. He was taken to Allen Memorial Hospital in Waterloo, where he soon died.

Waterloo suffered in the agricultural recession of the 1980s; its major employers at the time were heavily rooted in agriculture. John Deere, the area’s largest employer, cut 10,000 jobs, and the Rath meatpacking plant closed altogether, losing 2,500 jobs. It is estimated that Waterloo lost 14% of its population during this time. Today the city enjoys a broader industrial base, as city leaders have sought to diversify its industrial and commercial mix. Deere remains a strong presence in the city, but employs only roughly one-third the number of people it did at its peak.

African American community

In 1910, a significant number of black railroad workers were brought in as strikebreakers to the Waterloo area. Black workers were relegated to 20 square blocks in Waterloo, an area that remains the east side to this day. In 1940, more black strikebreakers were brought in to work in the Rath meat plant. In 1948, a black strikebreaker killed a white union member. Instead of a race riot, a strike ensued against the Rath Company. The National Guard was called in to end the 73-day strike.

United Packinghouse Workers of America became the main union of the Rath Company, welcoming black workers, but United Auto Workers Local 838 continued to refuse black members. With the power of the union, Anna Mae Weems, Ada Treadwell, Charles Pearson and Jimmy Porter formed an anti-discrimination department at Rath by the 1950s. This department helped organize protests against local places that discriminated against blacks.

Porter would go on to organize the first black radio station in Waterloo, KBBG, in 1978. Weems became the head of the anti-discrimination department and local NAACP chapter.

On May 31, 1966, Eddie Wallace Sallis was found dead in the local jail. The black community felt the death was suspicious, and protests were held. On June 4, Weems led a march on city hall to encourage investigation into his death. The march led to the creation of the Waterloo Human Rights Commission, which lasted only a year due to lack of funding.

On Sept. 7, 1967, a city report, “Waterloo’s Unfinished Business”, was released. The report covered the ongoing problems in housing, education and employment faced by Waterloo’s black community. It confirmed the housing bias faced by black residents, that many of the schools were generally 80% of one race, and that 80% of black residents held service jobs. In a 2007 article, the Courier covered some changes in the 40 years since, finding that housing was now mostly divided by socioeconomic status, schools still violated the desegregation plan, and black unemployment was still double that of white residents.

The Iowa Supreme Court outlawed school segregation in 1868. A 1967 commission found most schools were still segregated and recommended immediate desegregation, which Mayor Lloyd Turner opposed. In 1969, the Waterloo school board voted to allow open enrollment in all their schools to encourage integration. Many parents felt it was not enough. Despite the efforts between 1967 and 1970, already-black schools in the area increased in their segregation.

By the 1960s, Rath was declining and jobs there were harder to come by. A federal government program trained 1,200 local youths with the promise of summer jobs, only to hire two as bricklayers. Starting in the summer months of 1966, Waterloo was subject to riots over race relations between the white community and the black community. Many white residents expressed confusion as to why riots were occurring in Waterloo, while younger black residents felt they were being treated unfairly, as their conditions seemed worse than those of their white neighbors. In 1967, the black population of Waterloo was equivalent to 8%, and according to the Courier, had a 4% unemployment rate. Waterloo was segregated at the time, as 95% of its black population lived in “East” Waterloo. While the white community felt East High was integrated with a 45% black student body, the black community pointed out that the elementary school in East Waterloo had only one white pupil.

Protests were mostly organized by black youths aged 16–25. Protests became riots when the youth felt protesting wasn’t effective. Protests turned into riots in July 1968 and reached a critical mass by September, with buildings on East 4th street torched and vandalized.

In August 1968, East High students Terri and Kathy Pearson gave the principal a list of grievances detailing how they felt the discrimination could be lessened. The principal refused to implement any of the requested changes. Student protests and walkouts continued through September. Students were angry that no African American history course was being taught, and that interracial dating was discouraged by teachers and administrators.

On Sep 13, 1968, during an East High School football game, police attempted to arrest a black youth. He resisted arrest, drawing attention of students in the stands. Black students fought and argued with the police, and police responded by using clubs and mace. The riot continued into the east side of Waterloo, with a subsequent fire that claimed a lumber mill and three homes. There was an attempt to set East High on fire as well. The riot lasted until midnight and resulted in seven officers injured and thirteen youths jailed. The National Guard was called in the following day. The riots were called off and a solution was reached thanks to civil rights leader William G Parker.

In 2003, Governor Tom Vilsack created a task force to close the racial achievement gap in Waterloo. In 2009, a fair housing report, “Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice”, compiled by Mullin & Lonergan Associates Inc., found Waterloo to be Iowa’s most segregated city. “Historical patterns of racial segregation persist in Waterloo. Of the 20 cities in Iowa with populations exceeding 25,000, Waterloo ranks as the most segregated.”

Many activists who participated in the original protests feel that Waterloo has remained the same. In 2015, The Huffington Post listed Waterloo as the 10th worst city for black Americans. The site noted that the city’s black residents have a 24% unemployment rate compared to 3.9% for whites, giving Waterloo one of the highest black unemployment rates among Midwest cities. Waterloo still has a higher percentage of blacks than most Iowa cities.

In December 2012, Derrick Ambrose Jr. was shot by a police officer. Ambrose’s family maintains he was unarmed, while the officer stated that he felt his life was in danger. A grand jury acquitted the officer. The shooting sparked outrage in the community.

Flood of 2008

June 2008 saw the worst flooding the Waterloo – Cedar Falls area had ever recorded; other major floods include the Great Flood of 1993. The flood control system constructed in the 1970s–90s largely functioned as designed.

In areas not protected by the system, the Cedar River poured out of its banks and into parking lots, backyards and across the farmland surrounding the city. Although much damage was done, the larger downstream city of Cedar Rapids was much harder hit.

An area of the west side of the downtown and an area near the former Rath Packing facility were impacted, not directly by water coming from the river, but as a result of storm runoff draining toward the river but then being trapped on the back side of the flood levy system. These areas did not have lift stations or alternate pumping capacity sufficient to force this water back to the river side of the control system. Areas where lift stations had been constructed (Virden Creek and East 7th Street) to pump this storm runoff into the swollen river remained largely dry (the east and north sides of downtown). Several areas experienced water seeping into basements due to high water-table levels.

According to the National Weather Service, the ten highest crests of the Cedar River recorded at East 7th Street in downtown Waterloo:

Crests reported in the 1960s and earlier were before completion of major flood control projects and therefore may not be directly comparable.

In September 2016, flood watches and warnings were put into effect for Waterloo and its surrounding cities. The crest was expected to just barely hit the height of the 2008 flood.

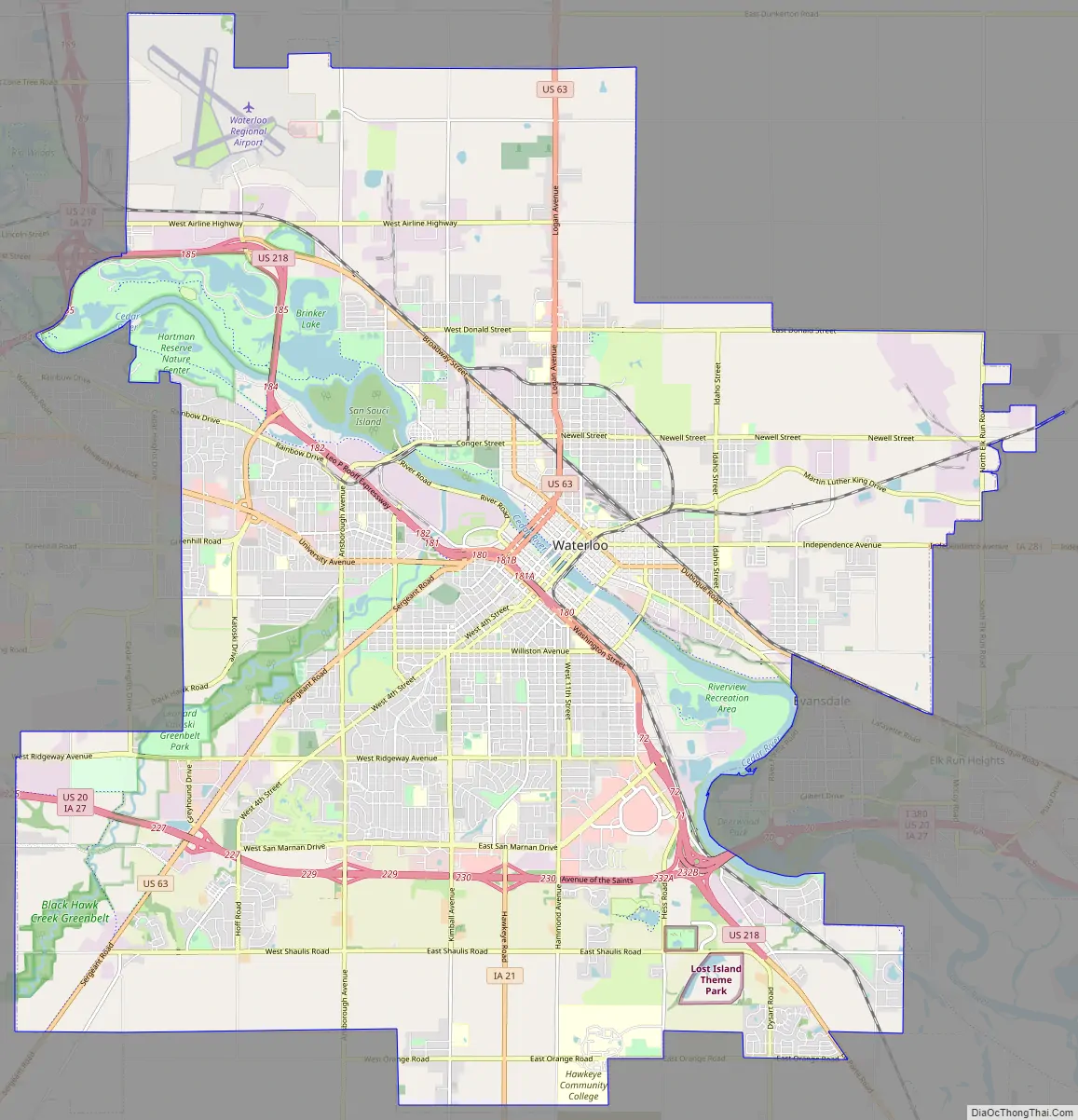

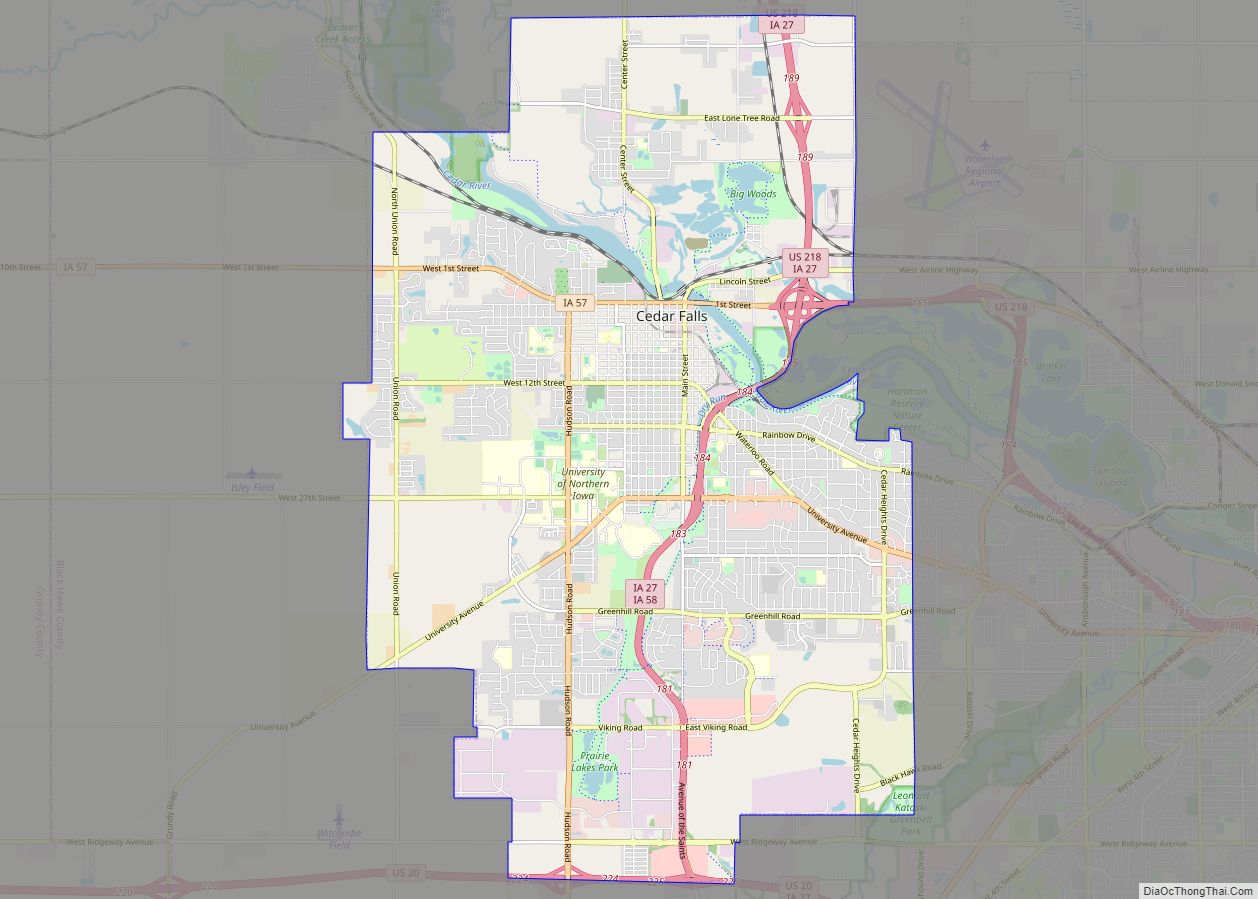

Waterloo Road Map

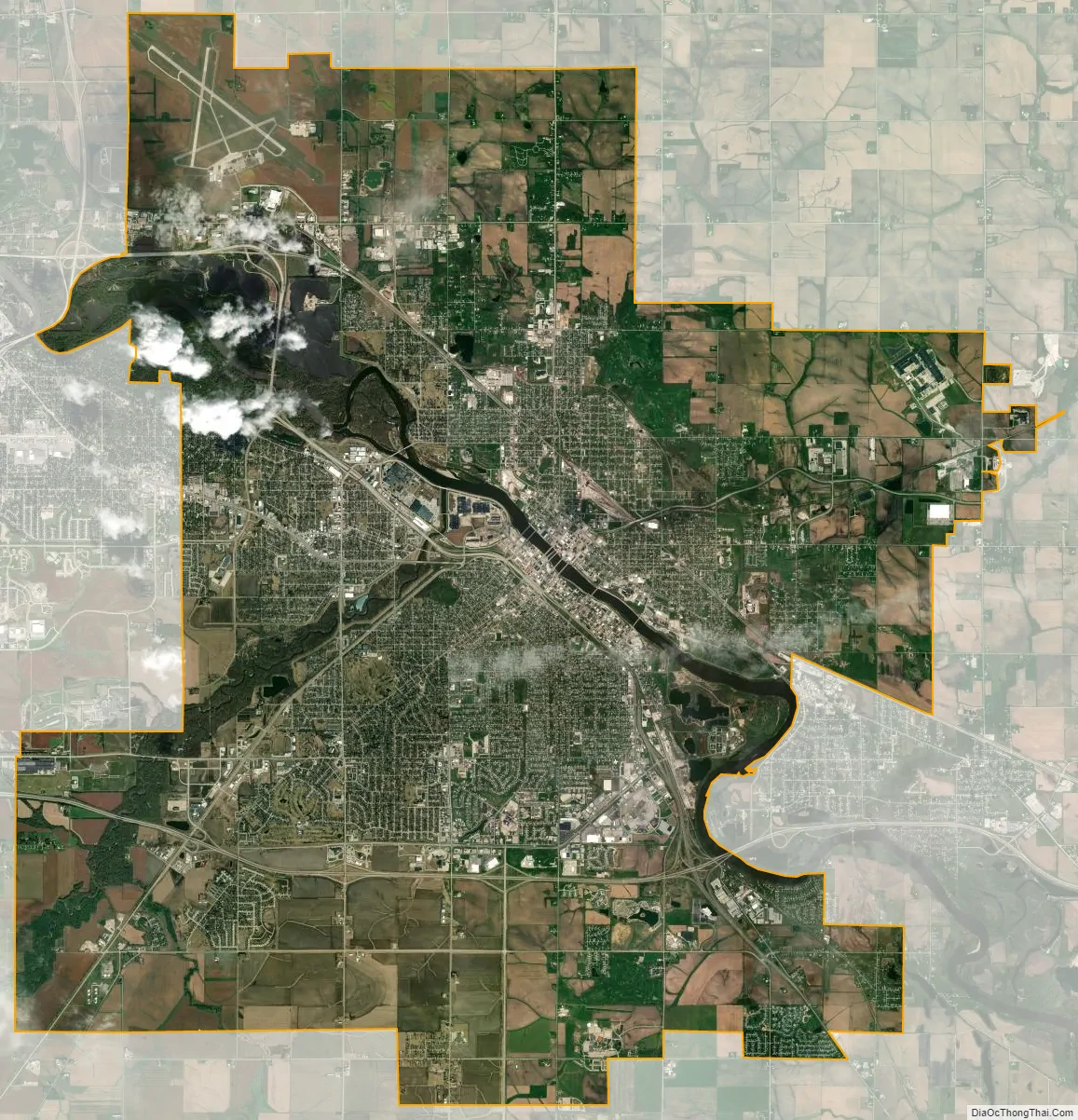

Waterloo city Satellite Map

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 63.23 square miles (163.76 km), of which 61.39 square miles (159.00 km) is land and 1.84 square miles (4.77 km) is water.

The average elevation of Waterloo is 846 feet above sea level. The population density is 1101 people per square mile, considered low for an urban area.

Climate

Waterloo has a humid continental climate zone (Köppen classification Dfa), typical of the state of Iowa, and is part of USDA Plant Hardiness zone 5a. The normal monthly mean temperature ranges from 18.5 °F (−7.5 °C) in January to 73.6 °F (23.1 °C) in July. On average, there are 22 nights annually with a low at or below 0 °F (−18 °C), 58 days annually with a high at or below freezing, and 16 days with a high at or above 90 °F (32 °C). As the mean first and last occurrence of freezing temperatures is October 1 and April 29, respectively, this allows for a growing season of 154 days. Temperature records range from −34 °F (−37 °C) on March 1, 1962, and January 16, 2009, up to 112 °F (44 °C) on July 13 and 14, 1936, during the Dust Bowl. The record cold daily maximum is −16 °F (−27 °C) on February 2, 1996, while conversely the record warm daily minimum is 80 °F (27 °C) on July 31, 1917, and August 16, 1988.

Normal annual precipitation equivalent is 34.60 inches (879 mm) spread over an average 112 days, with heavier rainfall in spring and summer, but observed annual rainfall has ranged from 17.35 to 53.07 inches (441 to 1,348 mm) in 1910 and 1993, respectively. The wettest month on record is July 1999 with 12.82 inches (326 mm); on the 2nd of that month, 5.49 inches (139 mm) of rain fell, making for the heaviest rainfall in a single calendar day. The driest months are October 1952 and November 1954 with trace amounts each.

Winter snowfall is moderate, and averages 35.3 inches (90 cm) per season, spread over an average 27 days, and snow cover of 1 inch (2.5 cm) or more is seen on 67 days, mostly from December to March. Winter snowfall has ranged from 11.6 inches (29.5 cm) in 1967–68 to 68.5 inches (174.0 cm) in 1904–05. The most snow in a calendar day and month is 13.2 inches (33.5 cm) and 33.9 inches (86.1 cm) on January 3, 1971, and in December 2000, respectively.

See also

Map of Iowa State and its subdivision:- Adair

- Adams

- Allamakee

- Appanoose

- Audubon

- Benton

- Black Hawk

- Boone

- Bremer

- Buchanan

- Buena Vista

- Butler

- Calhoun

- Carroll

- Cass

- Cedar

- Cerro Gordo

- Cherokee

- Chickasaw

- Clarke

- Clay

- Clayton

- Clinton

- Crawford

- Dallas

- Davis

- Decatur

- Delaware

- Des Moines

- Dickinson

- Dubuque

- Emmet

- Fayette

- Floyd

- Franklin

- Fremont

- Greene

- Grundy

- Guthrie

- Hamilton

- Hancock

- Hardin

- Harrison

- Henry

- Howard

- Humboldt

- Ida

- Iowa

- Jackson

- Jasper

- Jefferson

- Johnson

- Jones

- Keokuk

- Kossuth

- Lee

- Linn

- Louisa

- Lucas

- Lyon

- Madison

- Mahaska

- Marion

- Marshall

- Mills

- Mitchell

- Monona

- Monroe

- Montgomery

- Muscatine

- O'Brien

- Osceola

- Page

- Palo Alto

- Plymouth

- Pocahontas

- Polk

- Pottawattamie

- Poweshiek

- Ringgold

- Sac

- Scott

- Shelby

- Sioux

- Story

- Tama

- Taylor

- Union

- Van Buren

- Wapello

- Warren

- Washington

- Wayne

- Webster

- Winnebago

- Winneshiek

- Woodbury

- Worth

- Wright

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming