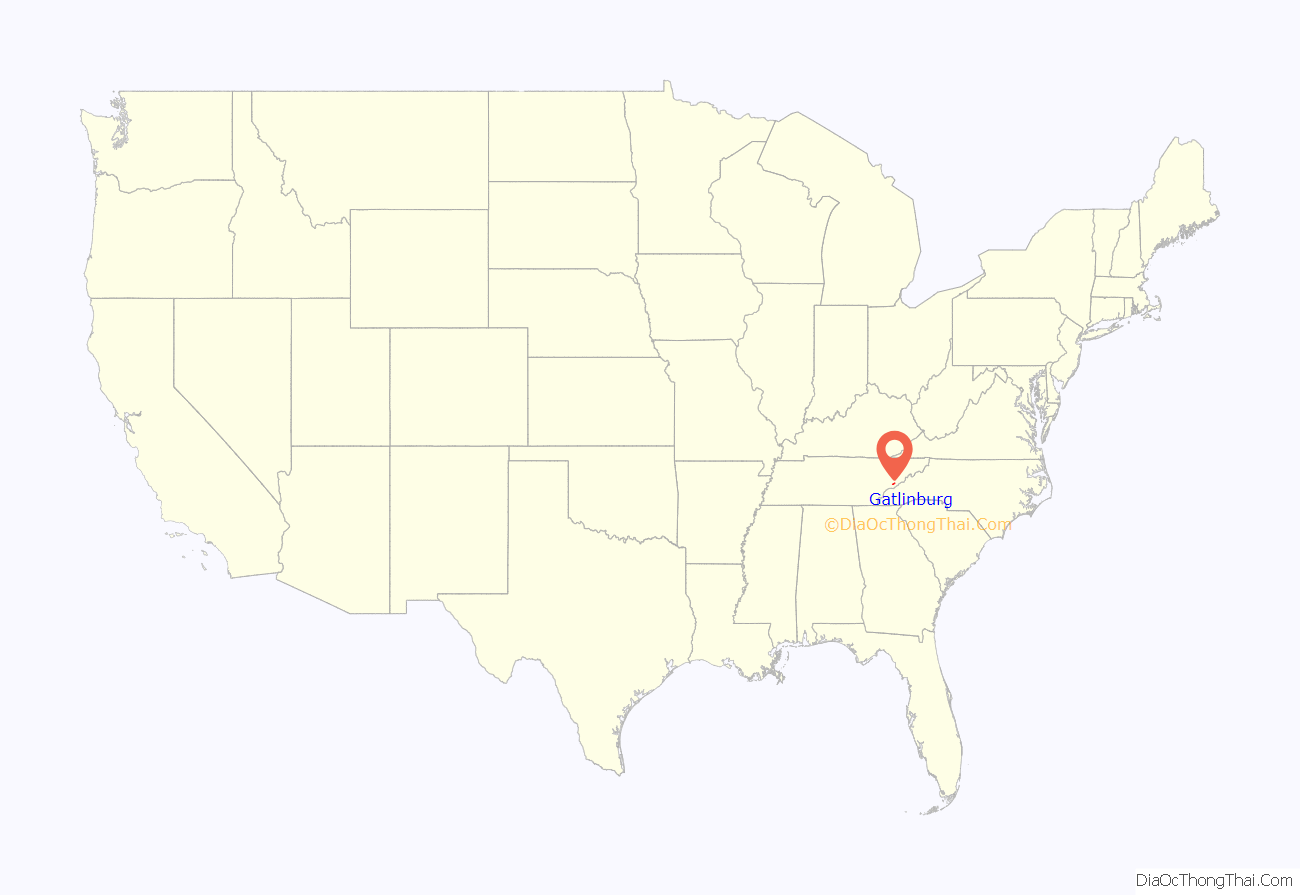

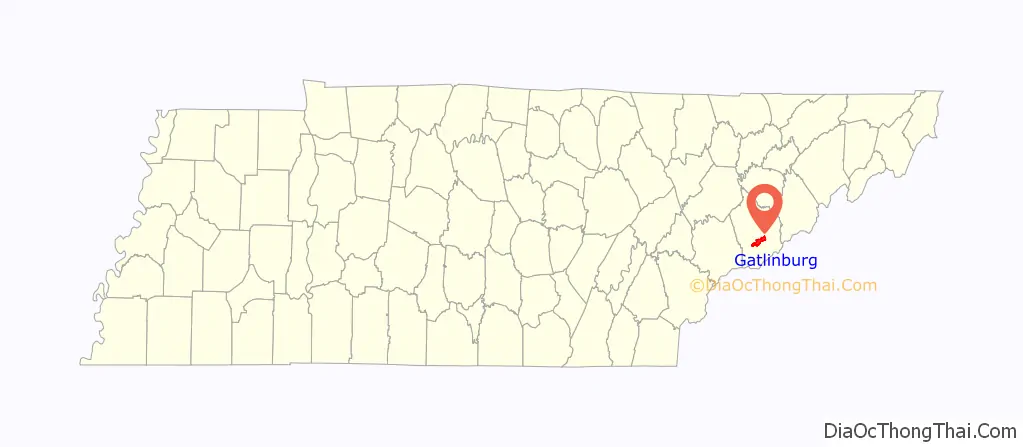

Gatlinburg is a mountain resort city in Sevier County, Tennessee, United States. It is located 39 miles (63 km) southeast of Knoxville and had a population of 3,944 at the 2010 Census and a U.S. Census population of 3,577 in 2020. It is a popular vacation resort, as it rests on the border of Great Smoky Mountains National Park along U.S. Route 441, which connects to Cherokee, North Carolina, on the southeast side of the national park. Prior to incorporation, the town was known as White Oak Flats, or just simply White Oak.

| Name: | Gatlinburg city |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 25 |

| LSAD Description: | city (suffix) |

| State: | Tennessee |

| County: | Sevier County |

| Incorporated: | 1945 |

| Elevation: | 1,289 ft (393 m) |

| Total Area: | 10.41 sq mi (26.97 km²) |

| Land Area: | 10.41 sq mi (26.97 km²) |

| Water Area: | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km²) |

| Total Population: | 3,577 |

| Population Density: | 343.48/sq mi (132.61/km²) |

| ZIP code: | 37738 |

| Area code: | 865 |

| FIPS code: | 4728800 |

| GNISfeature ID: | 1647737 |

| Website: | gatlinburgtn.gov |

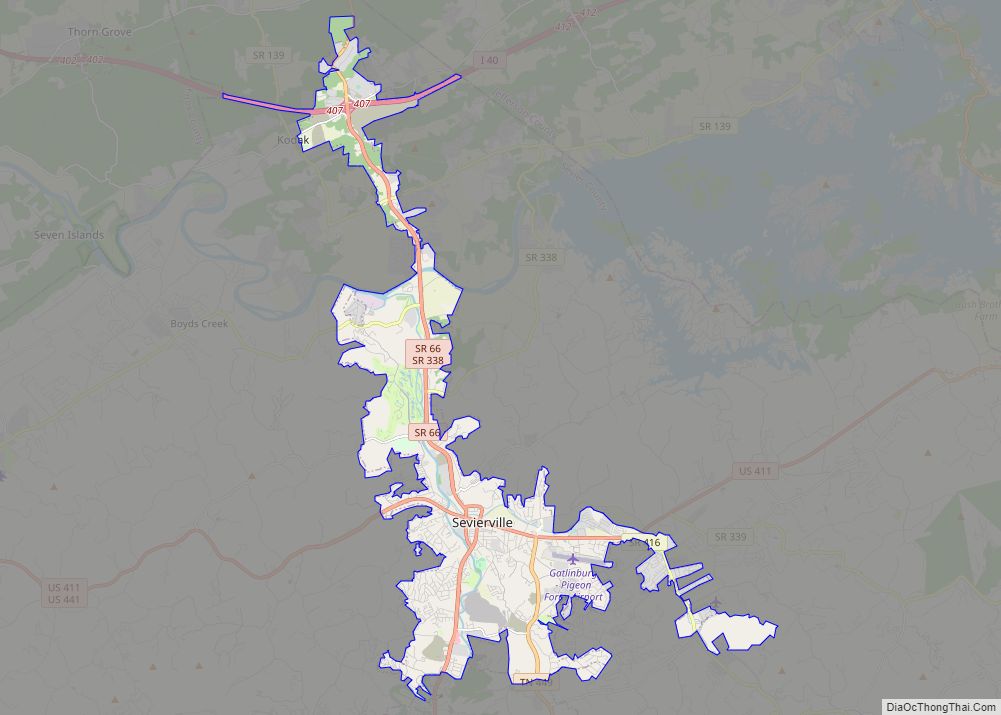

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

Gatlinburg location map. Where is Gatlinburg city?

History

Early history

For centuries, Cherokee hunters, as well as other Native American hunters before them, used a footpath known as the Indian Gap Trail to access the abundant game in the forests and coves of the Smokies. This trail connected the Great Indian Warpath with Rutherford Indian Trace, following the West Fork of the Little Pigeon River from modern-day Sevierville through modern-day Pigeon Forge, Gatlinburg, and the Sugarlands, crossing the crest of the Smokies along the slopes of Mount Collins, and descending into North Carolina along the banks of the Oconaluftee River. US-441 largely follows this same route today, although it crests at Newfound Gap rather than Indian Gap.

Although various 18th-century European and early American hunters and fur trappers probably traversed or camped in the flats where Gatlinburg is now situated, it was Edgefield, South Carolina, native William Ogle (1751–1803) who first decided to permanently settle in the area. With the help of the Cherokee, Ogle cut, hewed, and notched logs in the flats, planning to erect a cabin the following year. He returned home to Edgefield to retrieve his family and grow one final crop for supplies. However, shortly after his arrival in Edgefield, a malaria epidemic swept the low country, and Ogle succumbed to the disease in 1803.

His widow, Martha Huskey Ogle (1756–1827), moved the family to Virginia, where she had relatives. Sometime around 1806, Martha Huskey Ogle made the journey over Indian Gap Trail to what is now Gatlinburg with her brother, Peter Huskey, her daughter, Rebecca, and her daughter’s husband, James McCarter. William Ogle’s notched logs awaited them, and they erected a cabin near the confluence of Baskins Creek and the West Fork of the Little Pigeon shortly after their arrival. The cabin still stands today near the heart of Gatlinburg. James and Rebecca McCarter settled in the Cartertown district of Gatlinburg.

In the decade following the arrival of the Ogles, McCarters, and Huskeys in what came to be known as White Oak Flats, a steady stream of settlers moved into the area. Most were veterans of the American Revolution or War of 1812 who had converted the 50-acre (200,000 m) tracts they had received for service in war into deeds. Among these early settlers were Timothy Reagan (c. 1750–1830), John Ownby Jr. (1791–1857), and Henry Bohanon (1760–1842). Their descendants still live in the area today.

Radford Gatlin and the Civil War

In 1856, a post office was established in the general store of Radford Gatlin (c. 1798–1880), giving the town the name “Gatlinburg.” even though the town bore his name, Gatlin, who didn’t arrive in the flats until around 1854, constantly bickered with his neighbors. By 1857, a full-blown feud had erupted between the Gatlins and the Ogles, probably over Gatlin’s attempts to divert the town’s main road. The eve of the U.S. Civil War found Gatlin, who became a Confederate sympathizer, at odds with the residents of the flats, who were mostly pro-Union, and he was forced out in 1859.

Despite its anti-slavery sentiments, Gatlinburg, like most Smoky communities, tried to remain neutral during the war. This changed when a company of Confederate Colonel William Holland Thomas’ Legion occupied the town to protect the salt peter mines at Alum Cave, near the Tennessee-North Carolina border. Federal forces marched south from Knoxville and Sevierville to drive out Thomas’ men, who had built a small fort on Burg Hill. Lucinda Oakley Ogle, whose grandfather witnessed the ensuing skirmish, later recounted her grandfather’s recollections:

As the Union forces converged on the town, the outnumbered Confederates were forced to retreat across the Smokies to North Carolina. Confederate forces did not return, although sporadic small raids continued until the end of the war.

Early 20th century

In the 1880s, the invention of the band saw and the logging railroad led to a boom in the lumber industry. As forests throughout the Southeastern United States were harvested, lumber companies pushed deeper into the mountain areas of the Appalachian highlands. In 1901, Colonel W.B. Townsend established the Little River Lumber Company in Tuckaleechee Cove to the west, and lumber interests began buying up logging rights to vast tracts of forest in the Smokies.

Andrew Jackson Huff (1878–1949), originally of Greene County, was a pivotal figure in Gatlinburg at this time. Huff erected a sawmill in Gatlinburg in 1900, and local residents began supplementing their income by providing lodging to loggers and other lumber company officials. Tourists also began to trickle into the area, drawn to the Smokies by the writings of authors such as Mary Noailles Murfree and Horace Kephart, who wrote extensively about the region’s natural wonders.

In 1912, the Pi Beta Phi women’s fraternity established a settlement school (now Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts) in Gatlinburg after a survey of the region found the town to be most in need of educational facilities in the area. Although skeptical locals were initially worried that the fraternity might be religious propagandists or opportunists, the school’s enrollment grew from 33 to 134 in its first year of operation. Along with providing basic education to children in the area, the school’s staff created a small market for local crafts.

The journals and letters of the Pi Beta Phi settlement school’s staff are a valuable source of information about daily life in Gatlinburg in the early 1900s. Phyllis Higinbotham, a nurse from Toronto who worked at the school for six years, wrote of the mountain peoples’ confusion over the role of a nurse, their penchant for calling on her for minute issues, and her difficulties with Appalachian customs:

Higinbotham complained that there was an unhealthy “lack of variety” in the mountain peoples’ diet and that they weren’t open to new suggestions. Food was often “too starchy”, “not well cooked”, and supplemented with certain excesses:

Evelyn Bishop, a Pi Beta Phi who arrived at the school in 1913, reported that the mountain peoples’ relative isolation from American society allowed them to retain folklore that reflected their English and Scots-Irish ancestries, such as Elizabethan Era ballads:

Such isolation attracted folklorists such as Cecil Sharp of London to the area in the years following World War I. Sharp’s collection of Appalachian ballads was published in 1932.

National park

Extensive logging in the early 1900s led to increased calls by conservationists for federal action, and in 1911, Congress passed the Weeks Act to allow for the purchase of land for national forests. Authors such as Horace Kephart and Knoxville-area businesses began advocating for the creation of a national park in the Smokies that would be similar to Yellowstone or Yosemite in the Western United States. With the purchase of 76,000 acres (310 km) in the Little River Lumber Company tract in 1926, the movement quickly became a reality.

Andrew Huff spearheaded the movement in the Gatlinburg area, and he opened the first hotel in Gatlinburg – the Mountain View Hotel – in 1916. His son, Jack, established LeConte Lodge atop Mount Le Conte in 1926. In spite of resistance from lumberers at Elkmont and difficulties with the Tennessee legislature, Great Smoky Mountains National Park opened in 1934.

The park radically changed Gatlinburg. When the Pi Beta Phis arrived in 1912, Gatlinburg was a small hamlet with six houses, a blacksmith shop, a general store, a Baptist church, and a greater community of 600 individuals, most of whom lived in log cabins. In 1934, the first year the park was open, an estimated 40,000 visitors passed through the city. Within a year, this number had increased over twelvefold to 500,000. From 1940 to 1950, the cost per acre of land in Gatlinburg increased from $50 (equivalent to $1,000 in 2021) to $8,000 (equivalent to $90,000 in 2021).

While the park’s arrival benefited Gatlinburg and made many of the town’s residents wealthy, the tourism explosion led to problems with air quality and urban sprawl. Even in modern times, the town’s infrastructure is often pushed to the limit on peak vacation days and must consistently adapt to accommodate the growing number of tourists.

Fire of 1992

On the night of July 14, 1992, Gatlinburg gained national attention when an entire city block burned to the ground due to faulty wiring in a light fixture. The Ripley’s Believe It or Not! museum was consumed by the fire, along with an arcade, haunted house, and souvenir shop. The blaze was stopped before it could consume the adjacent 32-story Gatlinburg Space Needle. Known to locals as “Rebel Corner,” the block was completely rebuilt and reopened to visitors in 1995. Few artifacts from the Ripley’s Museum were salvaged, and those that survived are marked with that designation in the new museum. The fire prompted new downtown building codes and a new downtown fire station. Ripley’s has caught fire twice since it reopened, once in 2000 and again in 2003. Both of those fires, coincidentally, were caused by faulty light fixtures. The 2000 fire caused no damage, and the 2003 fire was contained to the building’s exterior, with the museum suffering minimal damage, primarily cosmetic.

Fire of 2016

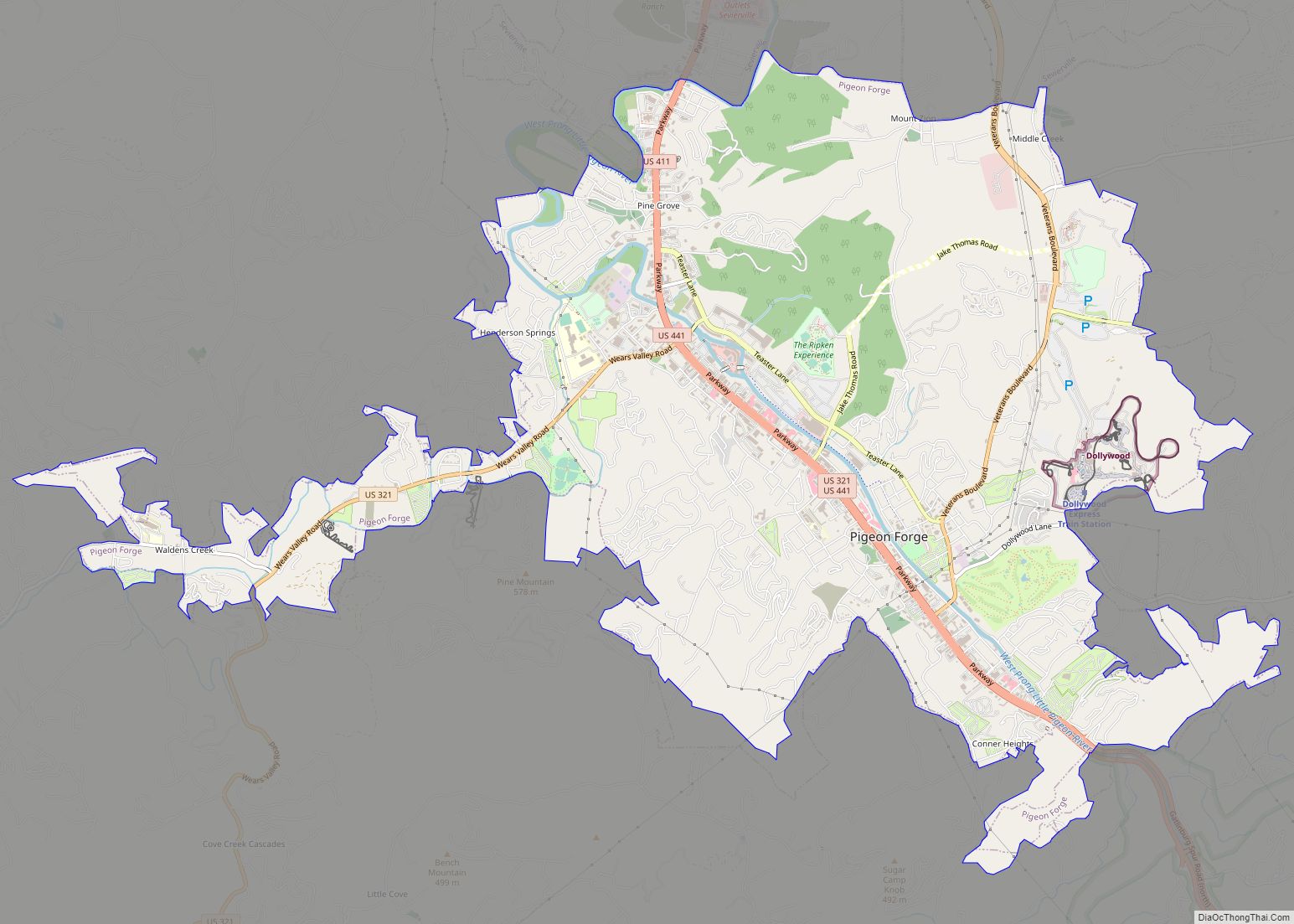

Starting in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park at Chimney Tops, a moderately contained wildfire was compounded by very strong winds – with gusts recorded up to 87 miles per hour (140 km/h) – and extremely dry conditions due to drought, causing it to spread down into Gatlinburg, Pigeon Forge, Pittman Center, and other nearby areas. It forced mass evacuations, and Governor Bill Haslam ordered the National Guard to the area. The center of Gatlinburg’s tourist district escaped heavy damage, but the surrounding wooded region was called “the apocalypse” by a fire department lieutenant. Approximately 14,000 people were evacuated that evening, more than 2,400 structures were damaged or destroyed, and damages totaled more than $500 million. Fourteen people died in the fires – some local citizens and some visiting tourists.

Following the fires, the town of Gatlinburg was shut down and considered a crime scene. The city reopened to residents only after a few days but maintained a strict curfew for more than a week, only reopening to the public after the curfew was lifted. In June 2017, the Sevier County district attorney dropped the charges against the two juveniles due to an inability to prove their actions led to the devastation that occurred in Gatlinburg five days later. According to D.A. James Dunn in an official statement, other factors played a key role, particularly the wind:

In May 2018, two Gatlinburg residents filed a $14.8 million lawsuit against the federal government for personal losses suffered in the fire.

Registered historic sites

- First Methodist Church, Gatlinburg: Designed by Charles I. Barber in Late Gothic Revival style.

- Settlement School Community Outreach Historic District: Phi Beta Pi established a settlement school in the area in 1912. This part of the designated historic district includes the Jennie Nicol Health Clinic Building, the Arrowcraft Shop, the Ogle Cabin, Cottage at the Creek, and Craftsman’s Fair Grounds and School Playground. The Settlement School Dormitories and Dwellings Historic District consists of Helmick House (Teacher’s Cottage), Stuart Dormitory, Ruth Barrett Smith Staff House, Old Wood Studio, a chicken coop, and a stock barn.

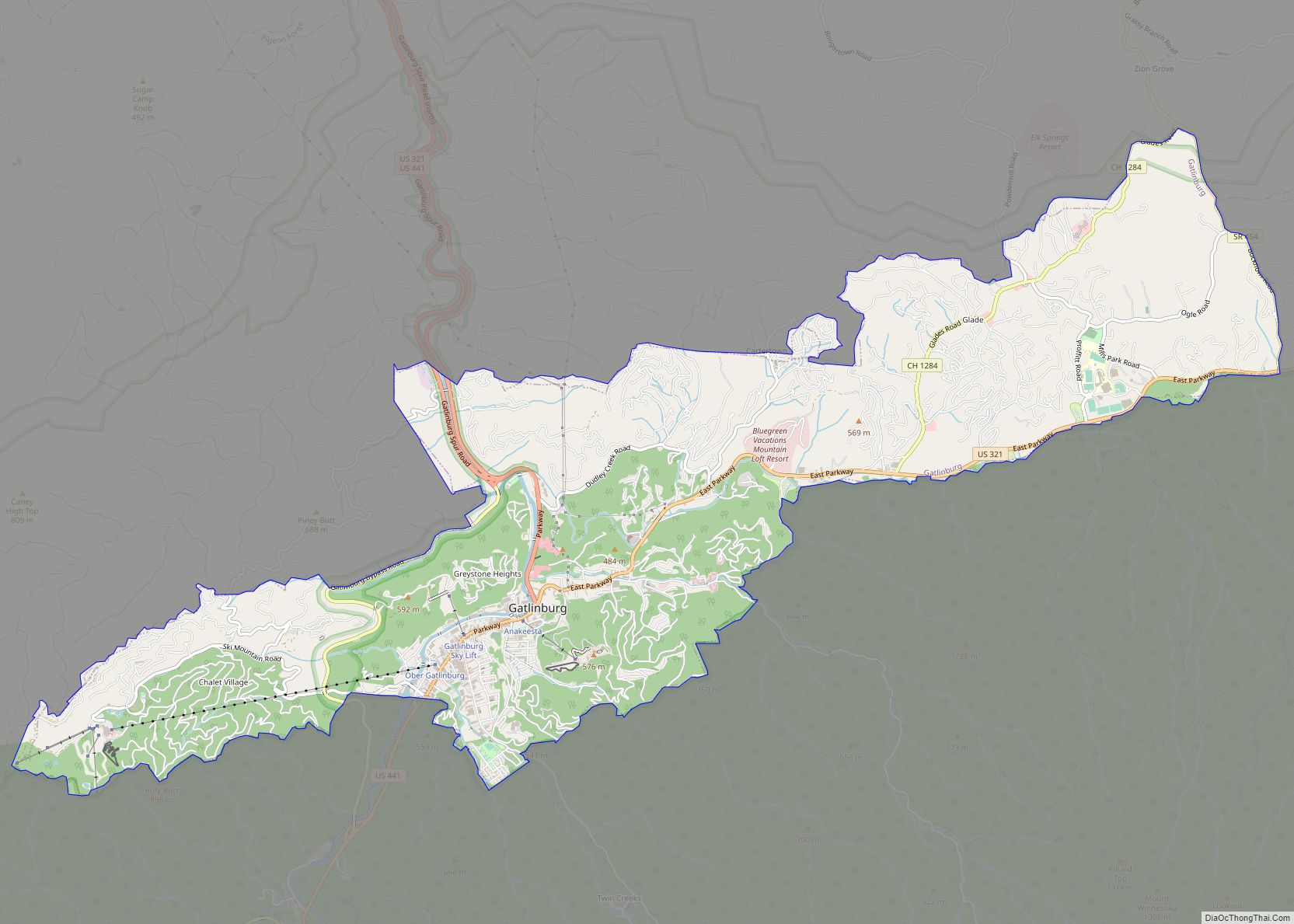

Gatlinburg Road Map

Gatlinburg city Satellite Map

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 10.1 square miles (26 km), all of which is land. It is surrounded on all sides by high ridges, with the Le Conte and Sugarland Mountain massifs rising to the south, Cove Mountain to the west, Big Ridge to the northeast, and Grapeyard Ridge to the east. The main watershed is the West Fork of the Little Pigeon River, which flows from its source on the slopes of Mount Collins to its junction with the Little Pigeon at Sevierville.

U.S. Route 441 is the main traffic artery in Gatlinburg, running through the center of town from north to south. Farther along 441, Pigeon Forge is approximately 6 miles (9.7 km) to the north, and Great Smoky Mountains National Park (viz. the Sugarlands) is approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) to the south. TN-73 (Little River Road) forks off from 441 in the Sugarlands and heads west for roughly 25 miles (40 km), connecting the Gatlinburg area with Townsend and Blount County. U.S. Route 321 enters Gatlinburg from Pigeon Forge and Wears Valley to the north before turning east and connecting the city to Newport and Cosby.

Climate

Gatlinburg has a humid subtropical climate (Koppen: Cfa) with hot, humid summers and cool, wet winters. Precipitation is heavy year round, peaking in the months of May–July, with October being the driest month, with only 3.19 inches (81 mm) of average precipitation. Snowfall is lower in the valley, averaging about 8 inches (20 cm) of annual snowfall.

See also

Map of Tennessee State and its subdivision:- Anderson

- Bedford

- Benton

- Bledsoe

- Blount

- Bradley

- Campbell

- Cannon

- Carroll

- Carter

- Cheatham

- Chester

- Claiborne

- Clay

- Cocke

- Coffee

- Crockett

- Cumberland

- Davidson

- Decatur

- DeKalb

- Dickson

- Dyer

- Fayette

- Fentress

- Franklin

- Gibson

- Giles

- Grainger

- Greene

- Grundy

- Hamblen

- Hamilton

- Hancock

- Hardeman

- Hardin

- Hawkins

- Haywood

- Henderson

- Henry

- Hickman

- Houston

- Humphreys

- Jackson

- Jefferson

- Johnson

- Knox

- Lake

- Lauderdale

- Lawrence

- Lewis

- Lincoln

- Loudon

- Macon

- Madison

- Marion

- Marshall

- Maury

- McMinn

- McNairy

- Meigs

- Monroe

- Montgomery

- Moore

- Morgan

- Obion

- Overton

- Perry

- Pickett

- Polk

- Putnam

- Rhea

- Roane

- Robertson

- Rutherford

- Scott

- Sequatchie

- Sevier

- Shelby

- Smith

- Stewart

- Sullivan

- Sumner

- Tipton

- Trousdale

- Unicoi

- Union

- Van Buren

- Warren

- Washington

- Wayne

- Weakley

- White

- Williamson

- Wilson

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming