Springfield is the capital of the U.S. state of Illinois and the county seat and largest city of Sangamon County. The city’s population was 114,394 at the 2020 census, which makes it the state’s seventh most-populous city, the second largest outside of the Chicago metropolitan area (after Rockford), and the largest in central Illinois. Approximately 208,000 residents live in the Springfield metropolitan area.

Springfield was settled by European-Americans in the late 1810s, around the time Illinois became a state. The most famous historic resident was Abraham Lincoln, who lived in Springfield from 1837 until 1861, when he went to the White House as President of the United States. Major tourist attractions include multiple sites connected with Lincoln including the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, Lincoln Home National Historic Site, Lincoln-Herndon Law Offices State Historic Site, and the Lincoln Tomb at Oak Ridge Cemetery.

Springfield lies in a valley and plain near the Sangamon River. Lake Springfield, a large artificial lake owned by the City Water, Light & Power company (CWLP), supplies the city with recreation and drinking water. Weather is fairly typical for middle latitude locations, with four distinct seasons including hot summers and cold winters. Spring and summer weather is like that of most Midwestern cities; thunderstorms may occur in late spring. Lying in Downstate Illinois, a part of Tornado Alley, tornadoes have hit the region on a few occasions.

The city has a mayor–council form of government and governs the Capital Township. The government of the state of Illinois is based in Springfield. State government institutions include the Illinois General Assembly, the Illinois Supreme Court and the Office of the Governor of Illinois. There are three public and three private high schools in Springfield. Public schools in Springfield are operated by District No. 186. Springfield’s economy is dominated by government jobs, plus the related lobbyists and firms that deal with the state and county governments and justice system, and health care and medicine.

| Name: | Springfield city |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 25 |

| LSAD Description: | city (suffix) |

| State: | Illinois |

| County: | Sangamon County |

| Founded: | April 10, 1821 (1821-04-10) |

| Elevation: | 600 ft (183 m) |

| Total Area: | 67.49 sq mi (174.79 km²) |

| Land Area: | 61.16 sq mi (158.41 km²) |

| Water Area: | 6.33 sq mi (16.38 km²) |

| Total Population: | 114,394 |

| Population Density: | 1,870.37/sq mi (722.16/km²) |

| ZIP code: | 62701–62708, 62711, 62712, 62715, 62716, 62719, 62722, 62723, 62726, 62736, 62739, 62756, 62757, 62761–62767, 62769, 62776, 62777, 62781, 62786, 62791, 62794, 62796 |

| Area code: | 217/447 |

| FIPS code: | 1772000 |

| GNISfeature ID: | 2395940 |

| Website: | www.springfield.il.us |

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

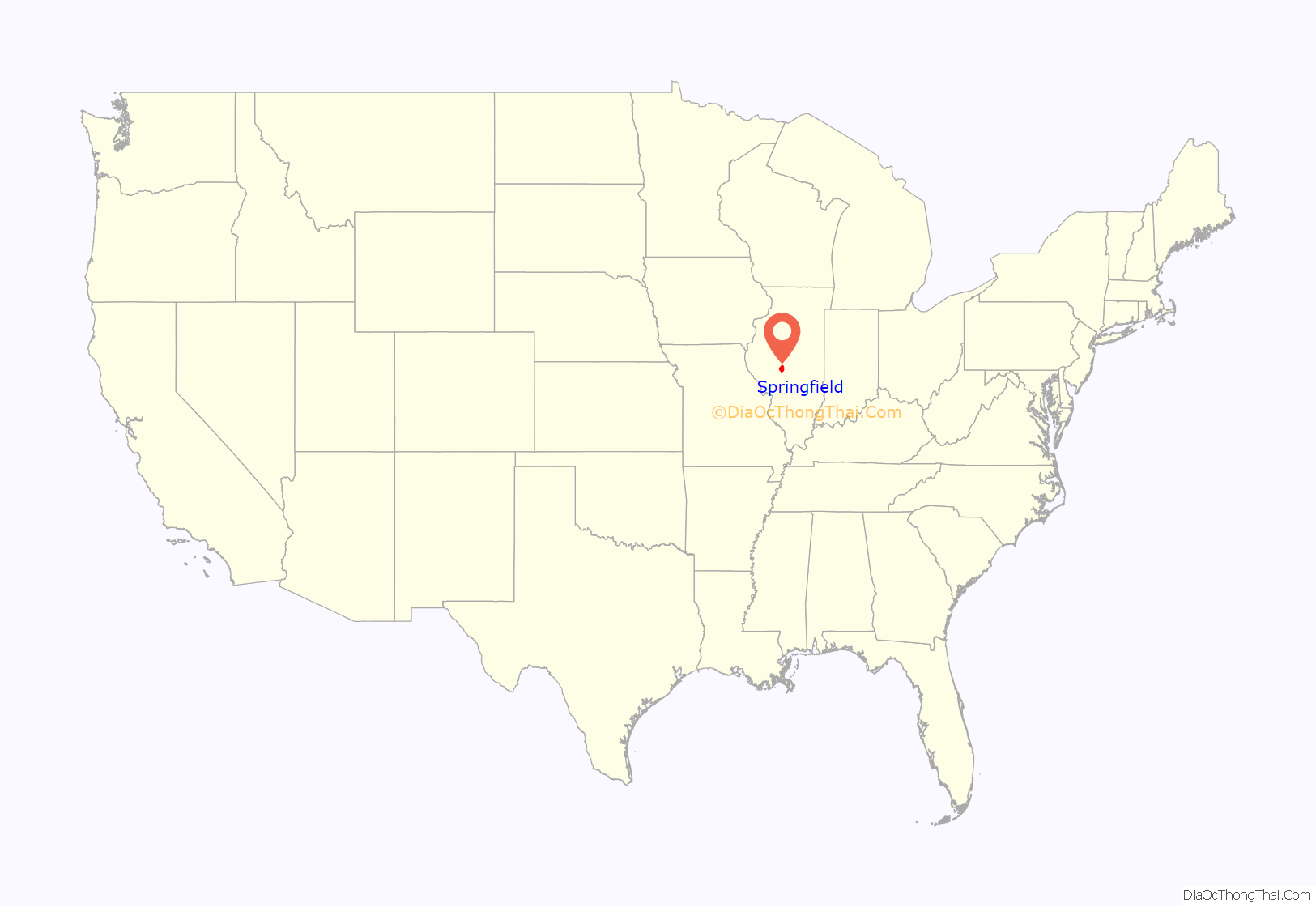

Springfield location map. Where is Springfield city?

History

Pre-Civil War

Settlers originally named this community as “Calhoun,” after Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, expressing their cultural ties. The land that Springfield now occupies was visited first by trappers and fur traders who came to the Sangamon River in 1818.

The first cabin was built in 1820, by John Kelly, after discovering the area to be plentiful of deer and wild game. He built his cabin upon a hill, overlooking a creek known eventually as the Town Branch. A stone marker on the north side of Jefferson street, halfway between 1st and College streets, marks the location of this original dwelling. A second stone marker at the NW corner of 2nd and Jefferson, often mistaken for the original home site, marks instead the location of the first county courthouse, which was later built on Kelly’s property. In 1821, Calhoun was designated as the county seat of Sangamon County due to its location, fertile soil and trading opportunities.

Settlers from Kentucky, Virginia, and North Carolina came to the developing settlement. By 1832, Senator Calhoun had fallen out of the favor with the public and the town renamed itself as Springfield. According to local history, the name was suggested by the wife of John Kelly, after Spring Creek, which ran through the area known as “Kelly’s Field”.

Kaskaskia was the first capital of the Illinois Territory from its organization in 1809, continuing through statehood in 1818, and through the first year as a state in 1819. Vandalia was the second state capital of Illinois, from 1819 to 1839. Springfield was designated in 1839 as the third capital, and has continued to be so. The designation was largely due to the efforts of Abraham Lincoln and his associates; nicknamed the “Long Nine” for their combined height of 54 feet (16 m).

The Potawatomi Trail of Death passed through here in 1838. The Native Americans were forced west to Indian Territory by the government’s Indian Removal policy.

Abraham Lincoln arrived in the Springfield area in 1831 when he was a young man, but he did not live in the city until 1837. He spent the ensuing six years in New Salem, where he began his legal studies, joined the state militia, and was elected to the Illinois General Assembly.

In 1837 Lincoln moved to Springfield, where he lived and worked for the next 24 years as a lawyer and politician. Lincoln delivered his Lyceum address in Springfield. His farewell speech when he left for Washington is a classic in American oratory.

Historian Kenneth J. Winkle (1998) examines the historiography concerning the development of the Second Party System (Whigs versus Democrats). He applied these ideas to the study of Springfield, a strong Whig enclave in a Democratic region. He chiefly studied poll books for presidential years. The rise of the Whig Party took place in 1836 in opposition to the presidential candidacy of Martin Van Buren and was consolidated in 1840. Springfield Whigs tend to validate several expectations of party characteristics as they were largely native-born, either in New England or Kentucky, professional or agricultural in occupation, and devoted to partisan organization. Abraham Lincoln’s career reflects the Whigs’ political rise but, by the 1840s, Springfield began to be dominated by Democratic politicians. Waves of new European immigrants had changed the city’s demographics and they became aligned with the Democrats, who made more effort to assist and connect with them. By the 1860 presidential election, Lincoln was barely able to win his home city.

Winkle earlier had studied the effect of migration on residents’ political participation in Springfield during the 1850s. Widespread migration in the 19th-century United States produced frequent population turnover within Midwestern communities, which influenced patterns of voter turnout and office-holding. Examination of the manuscript census, poll books, and office-holding records reveals the effects of migration on the behavior and voting patterns of 8,000 participants in 10 elections in Springfield. Most voters were short-term residents who participated in only one or two elections during the 1850s. Fewer than 1% of all voters participated in all 10 elections.

Instead of producing political instability, however, rapid turnover enhanced the influence of the more stable residents. Migration was selective by age, occupation, wealth, and birthplace. Longer-term or “persistent” voters, as he terms them, tended to be wealthier, more highly skilled, more often native-born, and socially more stable than non-persisters. Officeholders were particularly persistent and socially and economically advantaged. Persisters represented a small “core community” of economically successful, socially homogeneous, and politically active voters and officeholders who controlled local political affairs, while most residents moved in and out of the city. Members of a tightly knit and exclusive “core community”, exemplified by Abraham Lincoln, blunted the potentially disruptive impact of migration on local communities.

The case of John Williams illustrates the important role of the merchant banker in the economic development of central Illinois before the Civil War. Williams began his career as a clerk in frontier stores and saved to begin his own business. Later, in addition to operating retail and wholesale stores, he acted as a local banker. He organized a national bank in Springfield. He was active in railroad promotion and as an agent for farm machinery.

During the mid-19th century, the spiritual needs of German Lutherans in the Midwest were not being tended. There had been a wave of migration after the 1848 revolutions, but without a related number of clergy. As a result of the efforts of such missionaries as Friedrich Wyneken, Wilhelm Loehe, and Wilhelm Sihler, additional Lutheran ministers were sent to the Midwest, Lutheran schools were opened, and Concordia Theological Seminary was founded in Ft. Wayne, Indiana in 1846.

The seminary moved to St. Louis, Missouri, in 1869, and then to Springfield in 1874. During the last half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod succeeded in serving the spiritual needs of Midwestern congregations by establishing additional seminaries from ministers trained at Concordia, and by developing a viable synodical tradition.

Civil War to 1900

Springfield became a major center of activity during the American Civil War. Illinois regiments trained there, the first ones under Ulysses S. Grant. He led his soldiers to a remarkable series of victories in 1861–62. The city was a political and financial center of Union support. New industries, businesses, and railroads were constructed to help support the war effort. The war’s first official death was a Springfield resident, Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth.

Camp Butler, located seven miles (11 km) northeast of Springfield, Illinois, opened in August 1861 as a training camp for Illinois soldiers. It also served as a camp for Confederate prisoners of war through 1865. In the beginning, Springfield residents visited the camp to take part in the excitement of a military venture, but many reacted sympathetically to mortally wounded and ill prisoners. While the city’s businesses prospered from camp traffic, drunken behavior and rowdiness on the part of the soldiers stationed there strained relations. Neither civil nor military authorities proved able to control disorderly outbreaks.

After the war ended in 1865, Springfield became a major hub in the Illinois railroad system. It was a center of government and farming. By 1900 it was also invested in coal mining and processing.

20th century

Local poet Vachel Lindsay’s notions of utopia were expressed in his only novel, The Golden Book of Springfield (1920), which draws on ideas of anarchistic socialism in projecting the progress of Lindsay’s hometown toward utopia.

The Dana–Thomas House is a Frank Lloyd Wright design built in 1902–03. Wright began work on the house in 1902. Commissioned by Susan Lawrence Dana, a local patron of the arts and public benefactor, Wright designed a house to harmonize with the owner’s devotion to the performance of music. Coordinating art glass designs for 250 windows, doors, and panels as well as over 200 light fixtures, Wright enlisted Oak Park artisans. The house is a radical departure from Victorian architectural traditions. Covering 12,000 square feet (1,100 m), the house contained vaulted ceilings and 16 major spaces. As the nation was changing, so Wright intended this structure to reflect the changes. Creating an organic and natural atmosphere, Wright saw himself as an “architect of democracy” and intended his work to be a monument to America’s social landscape.

It is the only historic site later acquired by the state exclusively because of its architectural merit. The structure was opened to the public as a museum house in September 1990; tours are available, 9:00 a.m.–4:00 p.m. Wednesdays through Sundays.

Sparked by the alleged rape of a white woman by a black man and the murder of a white engineer, supposedly also by a black man, in Springfield, and reportedly angered by the high degree of corruption in the city, rioting broke out on August 14, 1908, and continued for three days in a period of violence known as the Springfield race riot. Gangs of white youth and blue-collar workers attacked the predominantly black areas of the city known as the Levee district, where most black businesses were located, and the Badlands, where many black residences stood. At least sixteen people died as a result of the riot: nine black residents, and seven white residents who were associated with the mob, five of whom were killed by state militia and two committed suicide. The riot ended when the governor sent in more than 3,700 militiamen to patrol the city, but isolated incidents of white violence against blacks continued in Springfield into September.

21st century

On March 12, 2006, two F2 tornadoes hit the city, injuring 24 people, damaging hundreds of buildings, and causing $150 million in damages.

On February 10, 2007, then-senator Barack Obama announced his presidential candidacy in Springfield, standing on the grounds of the Old State Capitol. Senator Obama also used the Old State Capitol in Springfield as a backdrop when he announced Joe Biden as his running mate on August 23, 2008.

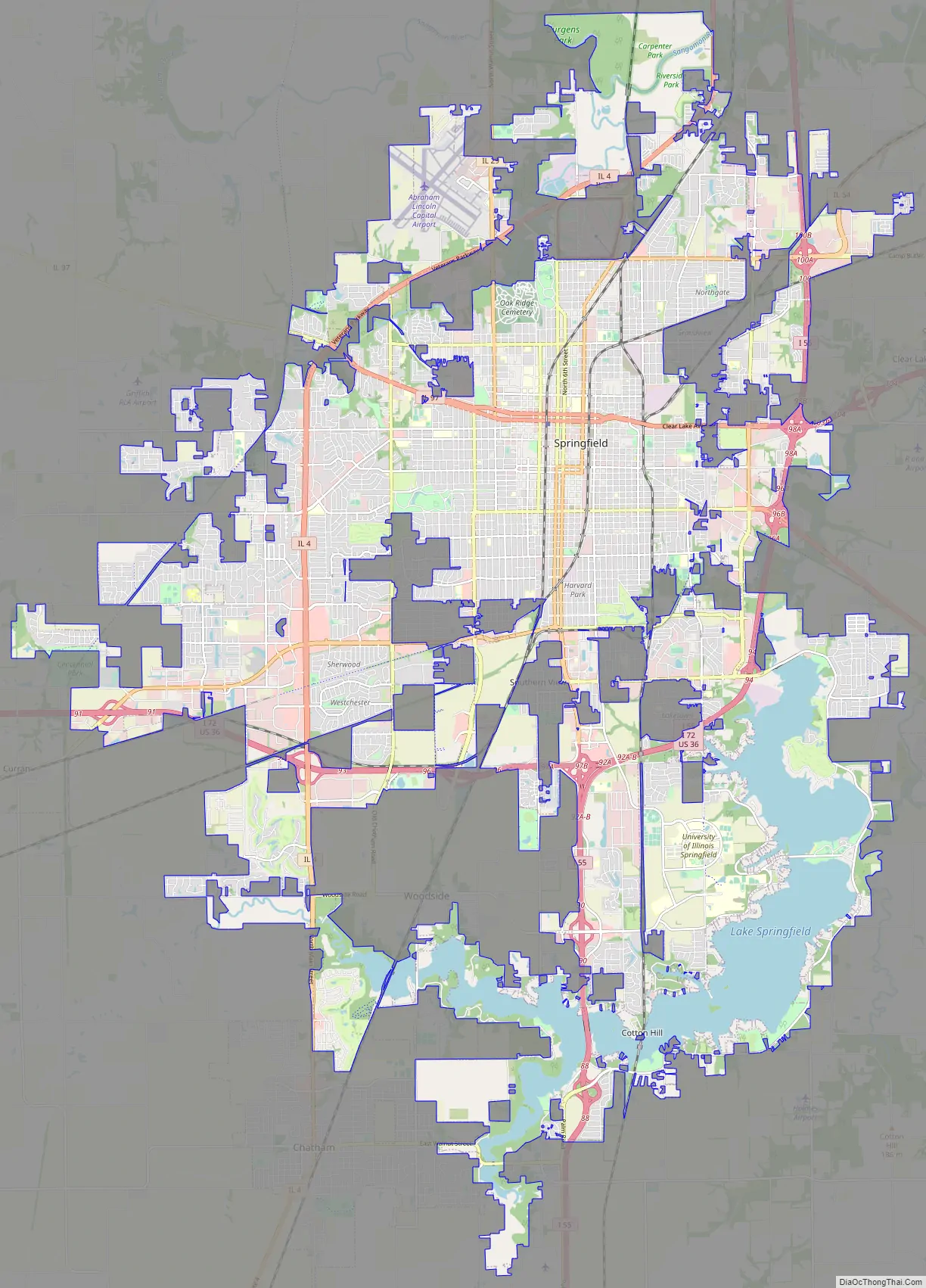

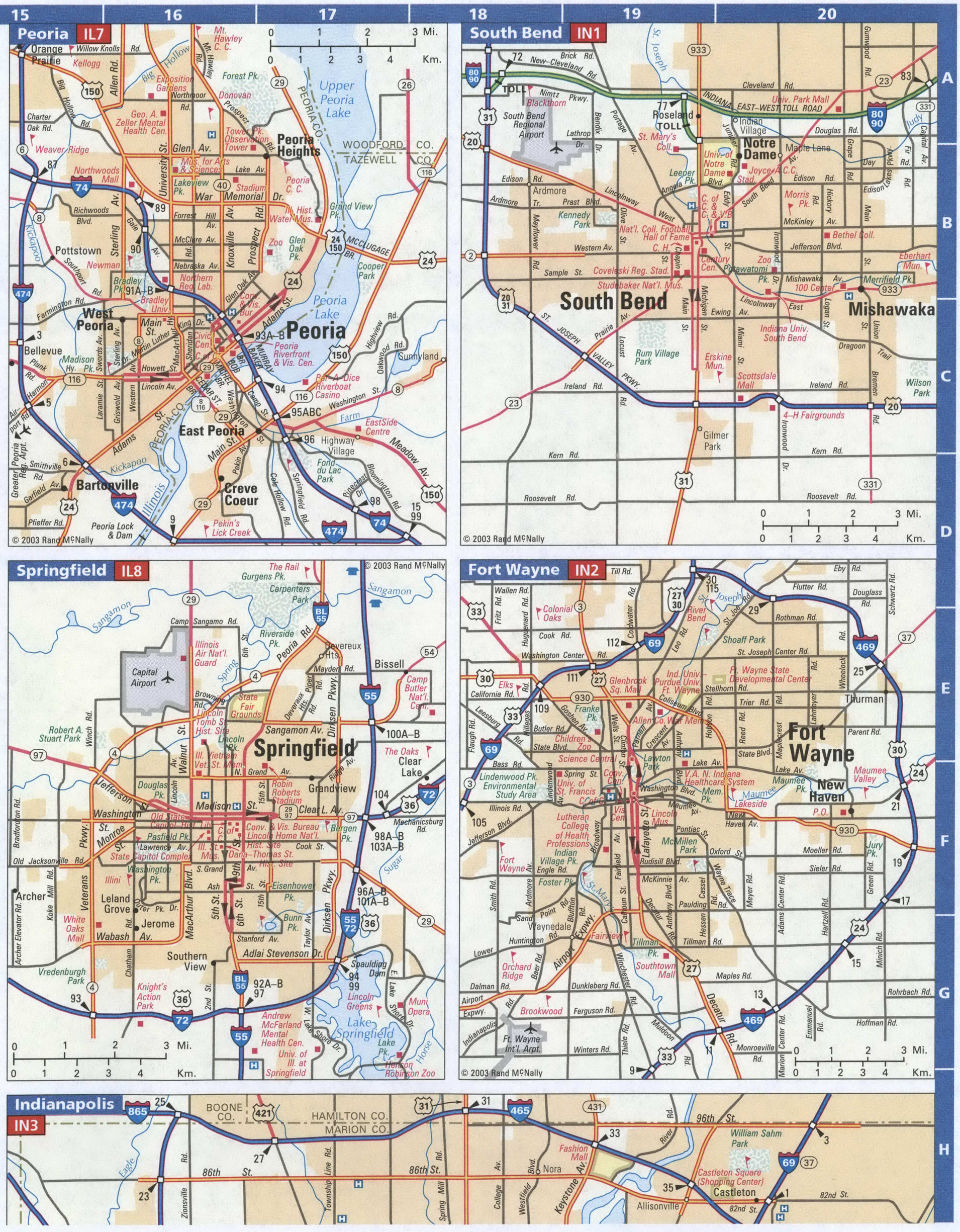

Springfield Road Map

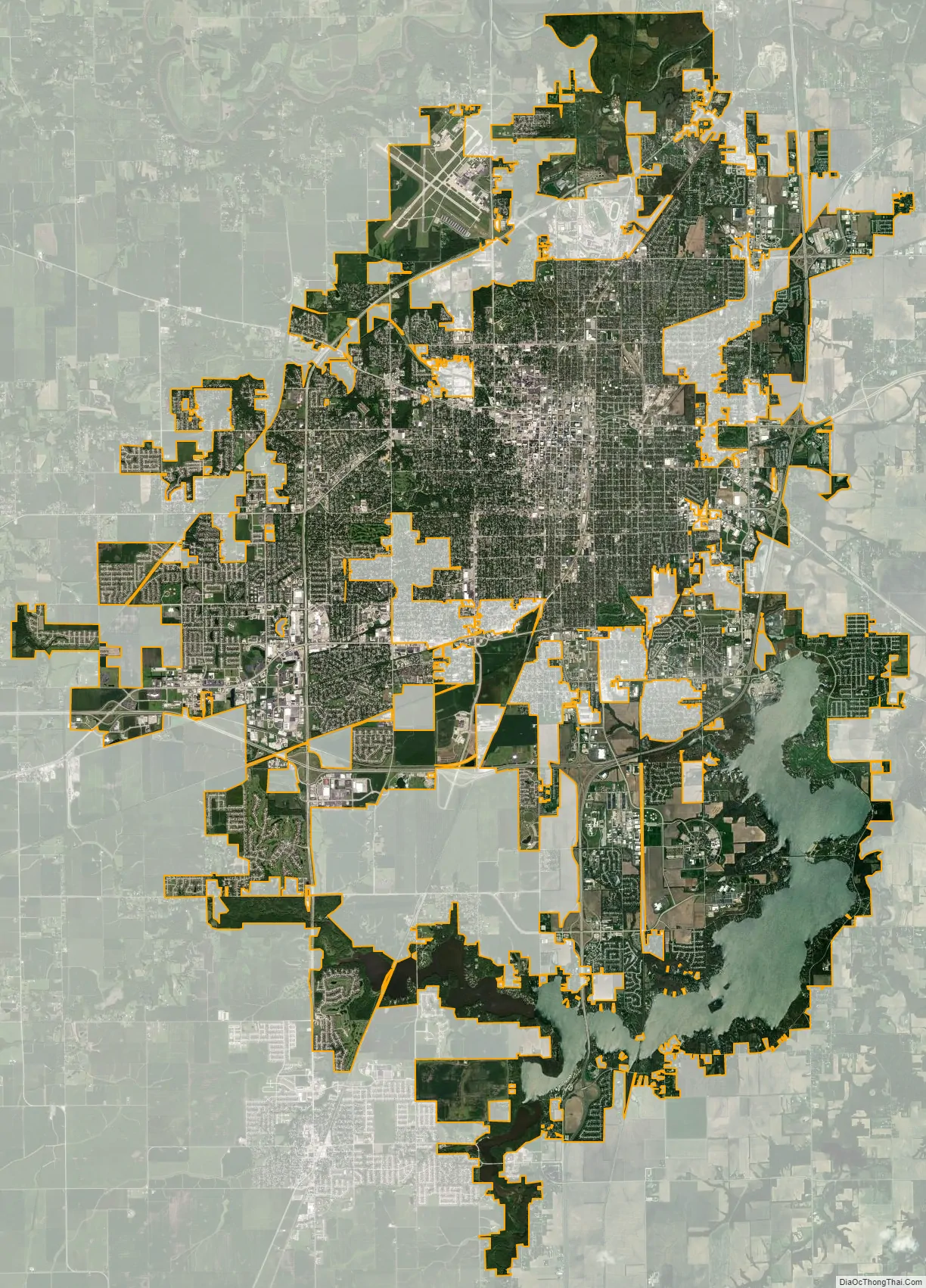

Springfield city Satellite Map

Geography

Located within the central section of Illinois, Springfield is 80 miles (130 km) northeast of St. Louis. The Champaign/Urbana area is to the east, Peoria is to the north, and Bloomington–Normal is to the northeast. Decatur is 40 miles (64 km) due east.

Topography

The city is at an elevation of 558 feet (170 m) above sea level. According to the 2010 census, Springfield has a total area of 65.764 square miles (170.33 km), of which 59.48 square miles (154.05 km) (or 90.44%) is land and 6.284 square miles (16.28 km) (or 9.56%) is water. The city is located in the Lower Illinois River Basin, in a large area known as Till Plain. Sangamon County, and the city of Springfield, are in the Springfield Plain subsection of Till Plain. The Plain is underlain by glacial till that was deposited by a large continental ice sheet that repeatedly covered the area during the Illinoian Stage.

The majority of the Lower Illinois River Basin is flat, with relief extending no more than 20 feet (6.1 m) in most areas, including the Springfield subsection of the plain. The differences in topography are based on the age of drift. The Springfield and Galesburg Plain subsections represent the oldest drift, Illinoian, while Wisconsinian drift resulted in end moraines on the Bloomington Ridged Plain subsection of Till Plain.

Lake Springfield is a 4,200-acre (1,700 ha) man-made reservoir owned by City Water, Light & Power, the largest municipally owned utility in Illinois. It was built and filled in 1935 by damming Lick Creek, a tributary of the Sangamon River which flows past Springfield’s northern outskirts. The lake is used primarily as a source for drinking water for the city of Springfield, also providing cooling water for the condensers at the power plant on the lake. It attracts approximately 600,000 visitors annually and its 57 miles (92 km) of shoreline is home to over 700 lakeside residences and eight public parks.

The term “full pool” describes the lake at 560 feet (170 m) above sea level and indicates the level at which the lake begins to flow over the dam’s spillway, if no gates are opened. Normal lake levels are generally somewhere below full pool, depending upon the season. During the drought from 1953 to 1955, lake levels dropped to their historical low, 547.44 feet (166.86 m) AMSL. The highest recorded lake levels were in December 1982, when the lake crested at 564 feet (172 m).

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Springfield falls within either a hot-summer humid continental climate (Dfa) if the 0 °C (32 °F) isotherm is used or a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) if the −3 °C (27 °F) isotherm is used. In recent years, winter temperatures have increased substantially while summer temperatures have remained mostly the same. Hot, humid summers and cold, rather snowy winters are the norm. Springfield is located on the farthest reaches of Tornado Alley, and as such, thunderstorms are a common occurrence throughout the spring and summer. From 1961 to 1990 the city of Springfield averaged 35.25 inches (895 mm) of precipitation per year. During that same period the average yearly temperature was 52.4 °F (11.3 °C), with a summer maximum of 76.5 °F (24.7 °C) in July and a winter minimum of 24.2 °F (−4.3 °C) in January.

From 1971 to 2000, NOAA data showed that Springfield’s annual mean temperature increased slightly to 52.7 °F (11.5 °C). During that period, July averaged 76.3 °F (24.6 °C), while January averaged 25.1 °F (−3.8 °C).

From 1981 to 2010, NOAA data showed that Springfield’s annual mean temperature increased slightly to 53.1 °F (11.7 °C). During that period, July averaged 76.0 °F (24.4 °C), while January averaged 26.9 °F (−2.8 °C).

On June 14, 1957, a tornado hit Springfield, killing two people. On March 12, 2006, the city was struck by two F2 tornadoes. The storm system which brought the two tornadoes hit the city around 8:30pm; no one died as a result of the weather. Springfield received a federal grant in February 2005 to help improve its tornado warning systems and new sirens were put in place in November 2006 after eight of the sirens failed during an April 2006 test, shortly after the tornadoes hit. The cost of the new sirens totaled $983,000. Although tornadoes are not uncommon in central Illinois, the March 12 tornadoes were the first to hit the actual city since the 1957 storm. The 2006 tornadoes followed nearly identical paths to that of the 1957 tornado.

Cityscape

Springfield proper is largely based on a grid street system, with numbered streets starting with the longitudinal First Street (which leads to the Illinois State Capitol) and leading to 32nd Street in the far eastern part of the city. Previously, the city had four distinct boundary streets: North, South, East, and West Grand Avenues. Since expansion, West Grand Avenue became MacArthur Boulevard and East Grand became 19th Street on the north side and 18th Street on the south side. 18th Street has since been renamed after Martin Luther King Jr. North and South Grand Avenues (which run east–west) have remained important corridors in the city. At South Grand Avenue and Eleventh Street, the old “South Town District” lies, with the City of Springfield undertaking a significant redevelopment project there.

Latitudinal streets range from names of presidents in the downtown area to names of notable people in Springfield and Illinois to names of institutions of higher education, especially in the Harvard Park neighborhood.

Springfield has at least twenty separately designated neighborhoods, though not all are incorporated with associations. They include: Benedictine District, Bunn Park, the Cabbage Patch, Downtown, Eastsview, Enos Park, Glen Aire, Harvard Park, Hawthorne Place, Historic West Side, Laketown, Lincoln Park, Mather and Wells, Medical District, Near South, Northgate, Oak Ridge, Old Aristocracy Hill, Pillsbury District, Shalom, Springfield Lakeshore, Toronto, Twin Lakes, UIS Campus, Victoria Lake, Vinegar Hill, and Westchester neighborhoods.

The Lincoln Park Neighborhood is an area bordered by 3rd Street on its west, Black Avenue on the north, 8th street on the east and North Grand Avenue. The neighborhood is not far from Lincoln’s Tomb on Monument Avenue.

Springfield also encompasses four different suburban villages that have their own municipal governments. They include Jerome, Leland Grove, Southern View, and Grandview.

See also

Map of Illinois State and its subdivision:- Adams

- Alexander

- Bond

- Boone

- Brown

- Bureau

- Calhoun

- Carroll

- Cass

- Champaign

- Christian

- Clark

- Clay

- Clinton

- Coles

- Cook

- Crawford

- Cumberland

- De Kalb

- De Witt

- Douglas

- Dupage

- Edgar

- Edwards

- Effingham

- Fayette

- Ford

- Franklin

- Fulton

- Gallatin

- Greene

- Grundy

- Hamilton

- Hancock

- Hardin

- Henderson

- Henry

- Iroquois

- Jackson

- Jasper

- Jefferson

- Jersey

- Jo Daviess

- Johnson

- Kane

- Kankakee

- Kendall

- Knox

- La Salle

- Lake

- Lake Michigan

- Lawrence

- Lee

- Livingston

- Logan

- Macon

- Macoupin

- Madison

- Marion

- Marshall

- Mason

- Massac

- McDonough

- McHenry

- McLean

- Menard

- Mercer

- Monroe

- Montgomery

- Morgan

- Moultrie

- Ogle

- Peoria

- Perry

- Piatt

- Pike

- Pope

- Pulaski

- Putnam

- Randolph

- Richland

- Rock Island

- Saint Clair

- Saline

- Sangamon

- Schuyler

- Scott

- Shelby

- Stark

- Stephenson

- Tazewell

- Union

- Vermilion

- Wabash

- Warren

- Washington

- Wayne

- White

- Whiteside

- Will

- Williamson

- Winnebago

- Woodford

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming