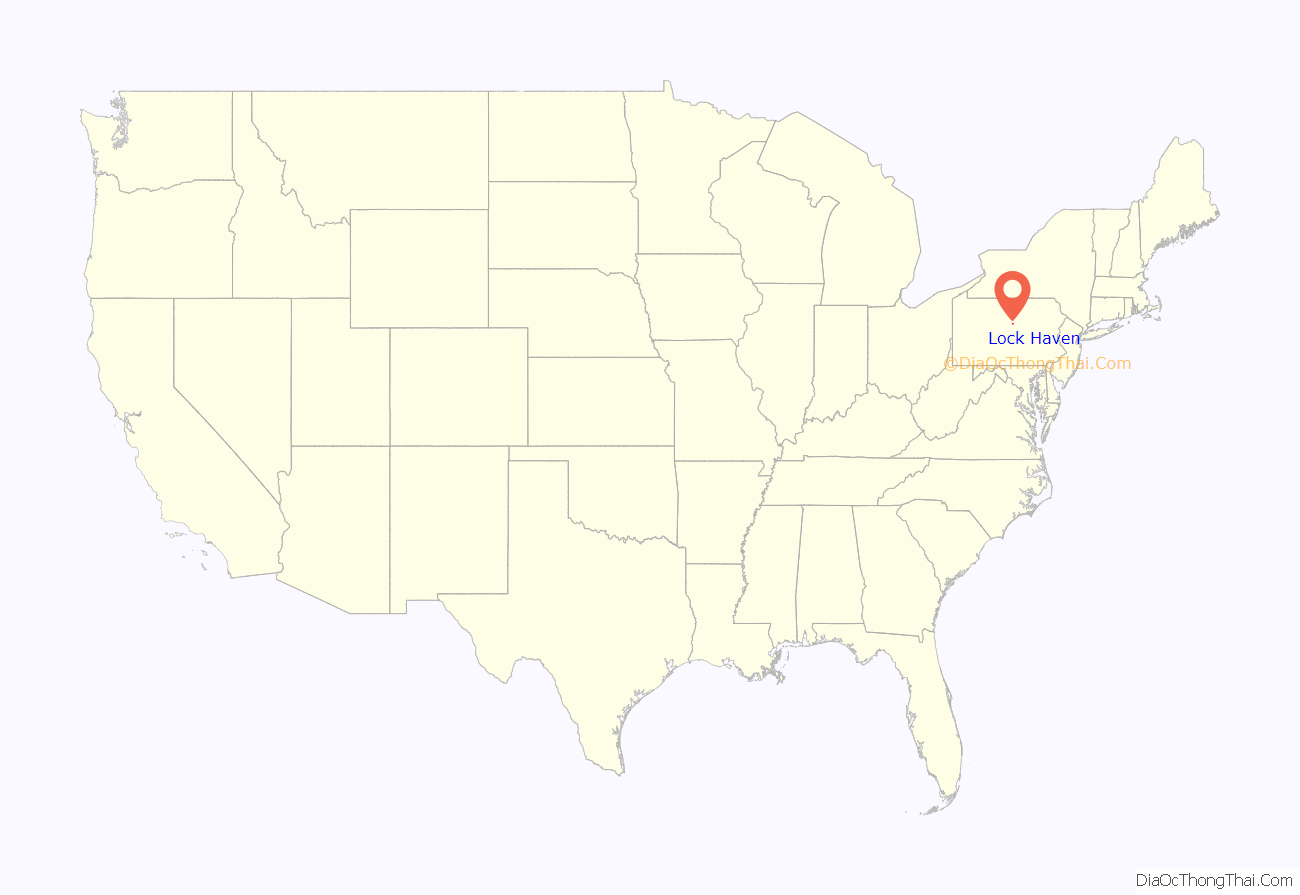

Lock Haven is the county seat of Clinton County, in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. Located near the confluence of the West Branch Susquehanna River and Bald Eagle Creek, it is the principal city of the Lock Haven Micropolitan Statistical Area, itself part of the Williamsport–Lock Haven combined statistical area. At the 2010 census, Lock Haven’s population was 9,772.

Built on a site long favored by pre-Columbian peoples, Lock Haven began in 1833 as a timber town and a haven for loggers, boatmen, and other travelers on the river or the West Branch Canal. Resource extraction and efficient transportation financed much of the city’s growth through the end of the 19th century. In the 20th century, a light-aircraft factory, a college, and a paper mill, along with many smaller enterprises, drove the economy. Frequent floods, especially in 1972, damaged local industry and led to a high rate of unemployment in the 1980s.

The city has three sites on the National Register of Historic Places—Memorial Park Site, a significant pre-Columbian archaeological find; Heisey House, a Victorian-era museum; and Water Street District, an area with a mix of 19th- and 20th-century architecture. A levee, completed in 1995, protects the city from further flooding. While industry remains important to the city, about a third of Lock Haven’s workforce is employed in education, health care, or social services.

| Name: | Lock Haven city |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 25 |

| LSAD Description: | city (suffix) |

| State: | Pennsylvania |

| County: | Clinton County |

| Elevation: | 561 ft (171 m) |

| Total Area: | 2.67 sq mi (6.91 km²) |

| Land Area: | 2.50 sq mi (6.47 km²) |

| Water Area: | 0.17 sq mi (0.44 km²) 6.44% |

| Total Population: | 8,108 |

| Population Density: | 3,248.40/sq mi (1,254.00/km²) |

| ZIP code: | 17745 |

| Area code: | 570 and 272 |

| FIPS code: | 4244128 |

| Website: | lockhavenpa.gov |

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

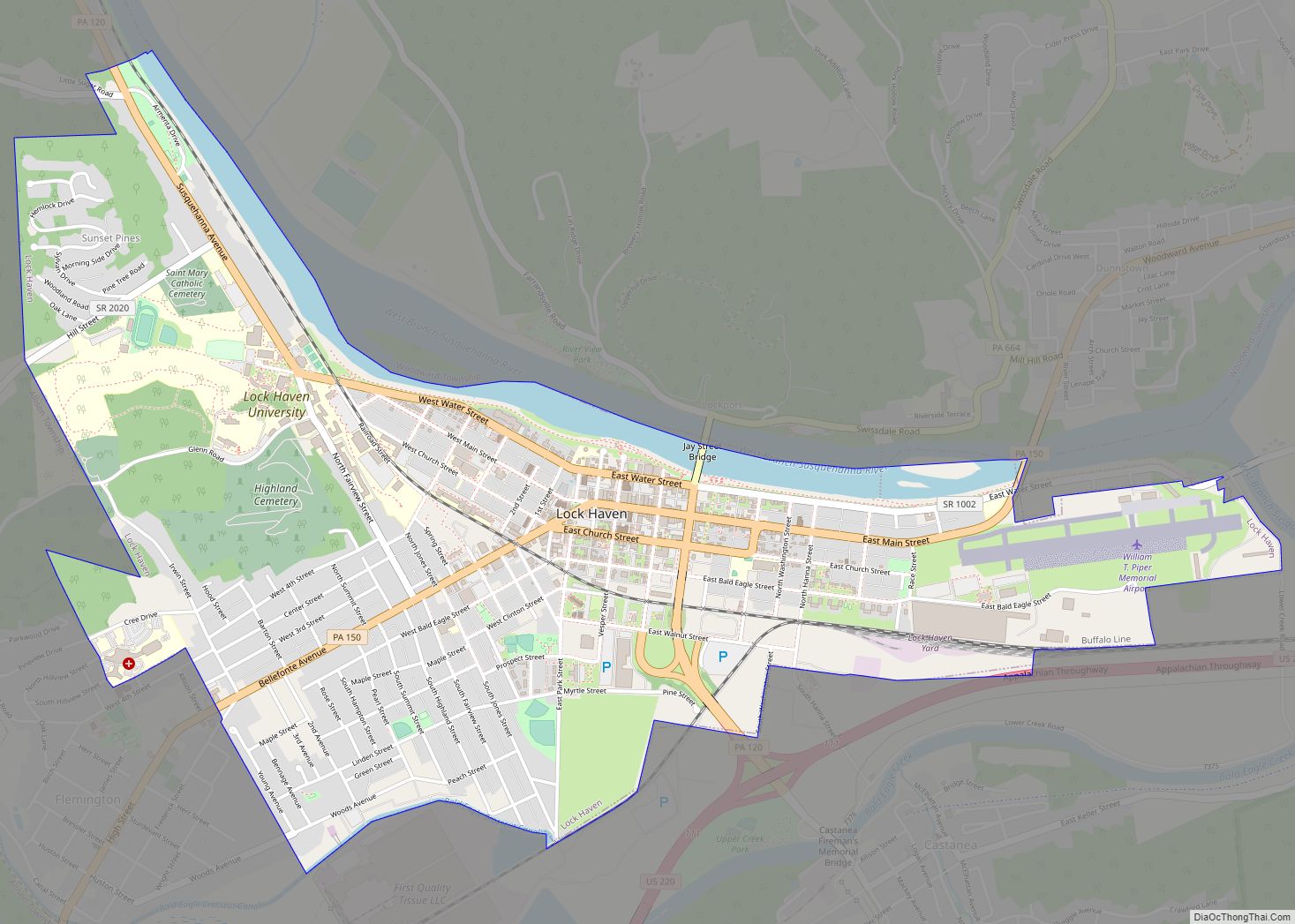

Lock Haven location map. Where is Lock Haven city?

History

Pre-European

The earliest settlers in Pennsylvania arrived from Asia between 12000 BCE and 8000 BCE, when the glaciers of the Pleistocene Ice Age were receding. Fluted point spearheads from this era, known as the Paleo-Indian Period, have been found in most parts of the state. Archeological discoveries at the Memorial Park Site 36Cn164 near the confluence of the West Branch Susquehanna River and Bald Eagle Creek collectively span about 8,000 years and represent every major prehistoric period from the Middle Archaic to the Late Woodland period. Prehistoric cultural periods over that span included the Middle Archaic starting at 6500 BCE; the Late Archaic starting at 3000 BCE; the Early Woodland starting at 1000 BCE; the Middle Woodland starting at 0 CE; and the Late Woodland starting at 900 CE. First contact with Europeans occurred in Pennsylvania between 1500 and 1600 CE.

Eighteenth century

In the early 18th century, a tribal confederacy known as the Six Nations of the Iroquois, headquartered in New York, ruled the Indian (Native American) tribes of Pennsylvania, including those who lived near what would become Lock Haven. Indian settlements in the area included three Munsee villages on the 325-acre (1.32 km) Great Island in the West Branch Susquehanna River at the mouth of Bald Eagle Creek. Four Indian trails, the Great Island Path, the Great Shamokin Path, the Bald Eagle Creek Path, and the Sinnemahoning Path, crossed the island, and a fifth, Logan’s Path, met Bald Eagle Creek Path a few miles upstream near the mouth of Fishing Creek. During the French and Indian War (1754–63), colonial militiamen on the Kittanning Expedition destroyed Munsee property on the Great Island and along the West Branch. By 1763, the Munsee had abandoned their island villages and other villages in the area.

With the signing of the first Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768, the British gained control from the Iroquois of lands south of the West Branch. However, white settlers continued to appropriate land, including tracts in and near the future site of Lock Haven, not covered by the treaty. In 1769, Cleary Campbell, the first white settler in the area, built a log cabin near the present site of Lock Haven University of Pennsylvania, and by 1773 William Reed, another settler, had built a cabin surrounded by a stockade and called it Reed’s Fort. It was the westernmost of 11 mostly primitive forts along the West Branch; Fort Augusta, located by the confluence of the East (or North) and West branches of the Susquehanna at what is now Sunbury, was the easternmost and most defensible. In response to settler incursions, and encouraged by the British during the American Revolution (1775–83), Indians attacked colonists and their settlements along the West Branch. Fort Reed and the other white settlements in the area were temporarily abandoned in 1778 during a general evacuation known as the Big Runaway. Hundreds of people fled along the river to Fort Augusta, about 50 miles (80 km) from Fort Reed; some did not return for five years. In 1784, the second Treaty of Fort Stanwix, between the Iroquois and the United States, transferred most of the remaining Indian territory in Pennsylvania, including what would become Lock Haven, to the state. The U.S. acquired the last remaining tract, the Erie Triangle, through a separate treaty and sold it to Pennsylvania in 1792.

Nineteenth century

Lock Haven was laid out as a town in 1833, and it became the county seat in 1839, when Clinton County was created out of parts of Lycoming and Centre counties. Incorporated as a borough in 1840 and as a city in 1870, Lock Haven prospered in the 19th century largely because of timber and transportation. The forests of Clinton County and counties upriver held a huge supply of white pine and hemlock as well as oak, ash, maple, poplar, cherry, beech, and magnolia. The wood was used locally for such things as frame houses, shingles, canal boats, and wooden bridges, and whole logs were floated to Chesapeake Bay and on to Baltimore, to make spars for ships. Log driving and log rafting, competing forms of transporting logs to sawmills, began along the West Branch around 1800. By 1830, slightly before the founding of the town, the lumber industry was well established.

The West Branch Canal, which opened in 1834, ran 73 miles (117 km) from Northumberland to Farrandsville, about 5 miles (8 km) upstream from Lock Haven. A state-funded extension called the Bald Eagle Cut ran from the West Branch through Lock Haven and Flemington to Bald Eagle Creek. A privately funded extension, the Bald Eagle and Spring Creek Navigation, eventually reached Bellefonte, 24 miles (39 km) upstream. Lock Haven’s founder, Jeremiah Church, and his brother, Willard, chose the town site in 1833 partly because of the river, the creek, and the canal. Church named the town Lock Haven because it had a canal lock and because it was a haven for loggers, boatmen, and other travelers. Over the next quarter century, canal boats 12 feet (4 m) wide and 80 feet (24 m) long carried passengers and mail as well as cargo such as coal, ashes for lye and soap, firewood, food, furniture, dry goods, and clothing. A rapid increase in Lock Haven’s population (to 830 by 1850) followed the opening of the canal.

A Lock Haven log boom, smaller than but otherwise similar to the Susquehanna Boom at Williamsport, was constructed in 1849. Large cribs of timbers weighted with tons of stone were arranged in the pool behind the Dunnstown Dam, named for a settlement on the shore opposite Lock Haven. The piers, about 150 feet (46 m) from one another, stretched in a line from the dam to a point 3 miles (5 km) upriver. Connected by timbers shackled together with iron yokes and rings, the piers anchored an enclosure into which the river current forced floating logs. Workers called boom rats sorted the captured logs, branded like cattle, for delivery to sawmills and other owners. Lock Haven became the lumber center of Clinton County and the site of many businesses related to forest products.

The Sunbury and Erie Railroad, renamed the Philadelphia and Erie Railroad in 1861, reached Lock Haven in 1859, and with it came a building boom. Hoping that the area’s coal, iron ore, white pine, and high-quality clay would produce significant future wealth, railroad investors led by Christopher and John Fallon financed a line to Lock Haven. On the strength of the railroad’s potential value to the city, local residents had invested heavily in housing, building large homes between 1854 and 1856. Although the Fallons’ coal and iron ventures failed, Gothic Revival, Greek Revival, and Italianate mansions and commercial buildings such as the Fallon House, a large hotel, remained, and the railroad provided a new mode of transport for the ongoing timber era. A second rail line, the Bald Eagle Valley Railroad, originally organized as the Tyrone and Lock Haven Railroad and completed in the 1860s, linked Lock Haven to Tyrone, 56 miles (90 km) to the southwest. The two rail lines soon became part of the network controlled by the Pennsylvania Railroad.

During the era of log floating, logjams sometimes occurred when logs struck an obstacle. Log rafts floating down the West Branch had to pass through chutes in canal dams. The rafts were commonly 28 feet (9 m) wide—narrow enough to pass through the chutes—and 150 feet (46 m) to 200 feet (61 m) long. In 1874, a large raft got wedged in the chute of the Dunnstown Dam and caused a jam that blocked the channel from bank to bank with a pile of logs 16 feet (5 m) high. The jam eventually trapped another 200 log rafts, and 2 canal boats, The Mammoth of Newport and The Sarah Dunbar.

In terms of volume, the peak of the lumber era in Pennsylvania arrived in about 1885, when 1.9 million logs went through the boom at Williamsport. These logs produced a total of 226 million board feet (530 thousand cubic metres) of sawed lumber. After that, production steadily declined throughout the state. Lock Haven’s timber business was also affected by flooding, which badly damaged the canals and destroyed the log boom in 1889.

The Central State Normal School, established to train teachers for central Pennsylvania, held its first classes in 1877 at a site overlooking the West Branch Susquehanna River. The small school, with enrollments below 150 until the 1940s, eventually became Lock Haven University of Pennsylvania. In the early 1880s, the New York and Pennsylvania Paper Mill in Castanea Township near Flemington began paper production on the site of a former sawmill; the paper mill remained a large employer until the end of the 20th century.

Twentieth century

As older forms of transportation such as the canal boat disappeared, new forms arose. One of these, the electric trolley, began operation in Lock Haven in 1894. The Lock Haven Electric Railway, managed by the Lock Haven Traction Company and after 1900 by the Susquehanna Traction Company, ran passenger trolleys between Lock Haven and Mill Hall, about 3 miles (5 km) to the west. The trolley line extended from the Philadelphia and Erie Railroad station in Lock Haven to a station of the Central Railroad of Pennsylvania, which served Mill Hall. The route went through Lock Haven’s downtown, close to the Normal School, across town to the trolley car barn on the southwest edge of the city, through Flemington, over the Bald Eagle Canal and Bald Eagle Creek, and on to Mill Hall via what was then known as the Lock Haven, Bellefonte, and Nittany Valley Turnpike. Plans to extend the line from Mill Hall to Salona, 3 miles (5 km) south of Mill Hall, and to Avis 10 miles (16 km) northeast of Lock Haven, were never carried out, and the line remained unconnected to other trolley lines. The system, always financially marginal, declined after World War I. Losing business to automobiles and buses, it ceased operations around 1930.

William T. Piper Sr. built the Piper Aircraft Corporation factory in Lock Haven in 1937 after the company’s Taylor Aircraft manufacturing plant in Bradford, Pennsylvania, was destroyed by fire. The factory began operations in a building that once housed a silk mill. As the company grew, the original factory expanded to include engineering and office buildings. Piper remained in the city until 1984, when its new owner, Lear-Siegler, moved production to Vero Beach, Florida. The Clinton County Historical Society opened the Piper Aviation Museum at the site of the former factory in 1985, and 10 years later the museum became an independent organization.

The state of Pennsylvania acquired Central State Normal School in 1915 and renamed it Lock Haven State Teachers College in 1927. Between 1942 and 1970, the student population grew from 146 to more than 2,300; the number of teaching faculty rose from 25 to 170, and the college carried out a large building program. The school’s name was changed to Lock Haven State College in 1960, and its emphasis shifted to include the humanities, fine arts, mathematics, and social sciences, as well as teacher education. Becoming Lock Haven University of Pennsylvania in 1983, it opened a branch campus in Clearfield, 48 miles (77 km) west of Lock Haven, in 1989.

An 8-acre (3.2 ha) industrial area in Castanea Township adjacent to Lock Haven was placed on the National Priorities List of uncontrolled hazardous waste sites (commonly referred to as Superfund sites) in 1982. Drake Chemical, which went bankrupt in 1981, made ingredients for pesticides and other compounds at the site from the 1960s to 1981. Starting in 1982, the United States Environmental Protection Agency began a clean-up of contaminated containers, buildings, and soils at the site and by the late 1990s had replaced the soils. Equipment to treat contaminated groundwater at the site was installed in 2000 and continues to operate.

Floods

Pennsylvania’s streams have frequently flooded. According to William H. Shank, the Native Americans of Pennsylvania warned white settlers that great floods occurred on the Delaware and Susquehanna rivers every 14 years. Shank tested this idea by tabulating the highest floods on record at key points throughout the state over a 200-year period and found that a major flood had occurred, on average, once every 25 years between 1784 and 1972. Big floods recorded at Harrisburg, on the main stem of the Susquehanna about 120 miles (190 km) downstream from Lock Haven, occurred in 1784, 1865, 1889, 1894, 1902, 1936, and 1972. Readings from the Williamsport stream gauge, 24 miles (39 km) below Lock Haven on the West Branch of the Susquehanna, showed major flooding between 1889 and 1972 in the same years as the Harrisburg station; in addition, a large flood occurred on the West Branch at Williamsport in 1946. Estimated flood-crest readings between 1847 and 1979—based on data from the National Weather Service flood gauge at Lock Haven—show that flooding likely occurred in the city 19 times in 132 years. The biggest flood occurred on March 18, 1936, when the river crested at 32.3 feet (9.8 m), which was about 11 feet (3.4 m) above the flood stage of 21 feet (6.4 m).

The third biggest flood, cresting at 29.8 feet (9.1 m) in Lock Haven, occurred on June 1, 1889, and coincided with the Johnstown Flood. The flood demolished Lock Haven’s log boom, and millions of feet of stored timber were swept away. The flood damaged the canals, which were subsequently abandoned, and destroyed the last of the canal boats based in the city.

The most damaging Lock Haven flood was caused by the remnants of Hurricane Agnes in 1972. The storm, just below hurricane strength when it reached the region, made landfall on June 22 near New York City. Agnes merged with a non-tropical low on June 23, and the combined system affected the northeastern United States until June 25. The combination produced widespread rains of 6 to 12 inches (152 to 305 mm) with local amounts up to 19 inches (483 mm) in western Schuylkill County, about 75 miles (121 km) southeast of Lock Haven. At Lock Haven, the river crested on June 23 at 31.3 feet (9.5 m), second only to the 1936 crest. The flood greatly damaged the paper mill and Piper Aircraft.

In 1992 federal, state, and local governments began construction of barriers to protect the city. The project included a levee of 36,000 feet (11,000 m) and a flood wall of 1,000 feet (300 m) along the Susquehanna River and Bald Eagle Creek, closure structures, retention basins, a pumping station, and some relocation of roads and buildings. Completed in 1995, the levee protected the city from high water in the year of the Blizzard of 1996, and again 2004, when rainfall from the remnants of Hurricane Ivan threatened the city.

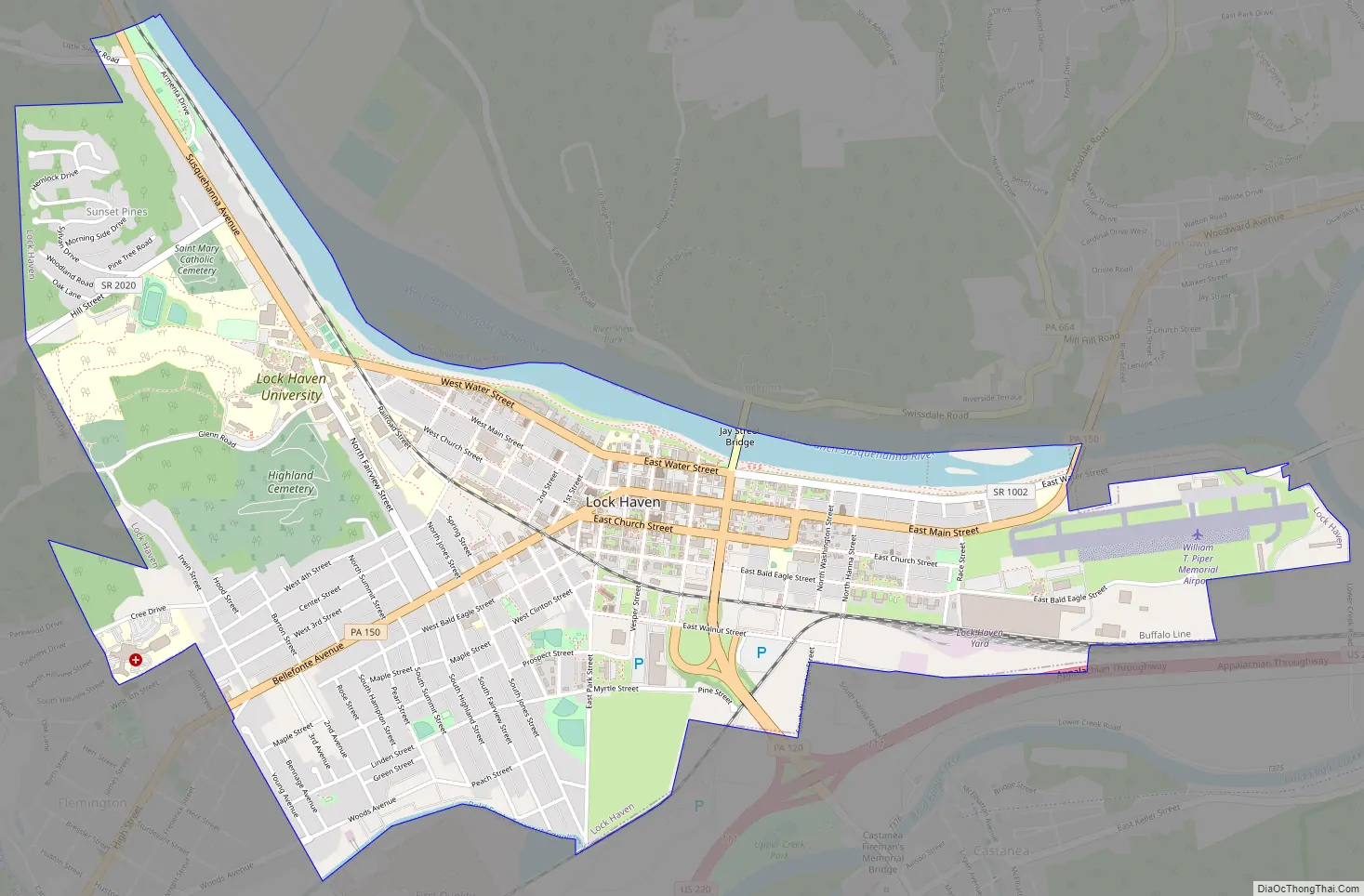

Lock Haven Road Map

Lock Haven city Satellite Map

Geography

Lock Haven is the county seat of Clinton County. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 2.7 square miles (7.0 km), 2.5 square miles (6.5 km) of which is land. About 0.2 square miles (0.5 km), 6 percent, is water.

Lock Haven is at 561 feet (171 m) above sea level near the confluence of Bald Eagle Creek and the West Branch Susquehanna River in north-central Pennsylvania. The city is approximately 200 miles (320 km) by highway northwest of Philadelphia and 175 miles (280 km) northeast of Pittsburgh. U.S. Route 220, a major transportation corridor, skirts the city on its southern edge, intersecting with Pennsylvania Route 120, which passes through the city and connects it with Renovo in northern Clinton County. Other highways entering Lock Haven include state routes 150, which connects to Avis, and 664.

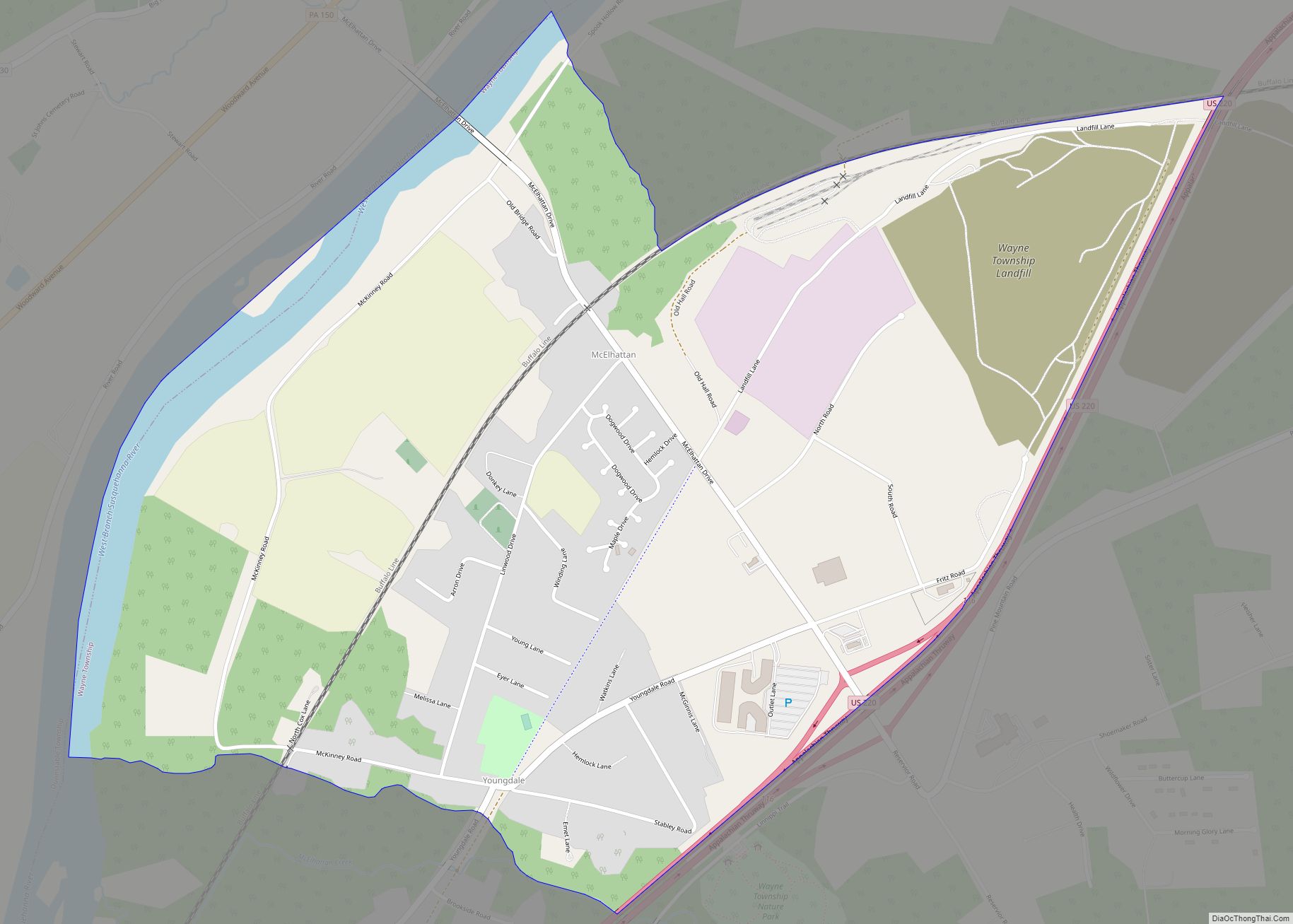

The city and nearby smaller communities—Castanea, Dunnstown, Flemington, and Mill Hall—are mainly at valley level in the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians, a mountain belt characterized by long, even valleys running between long continuous ridges. Bald Eagle Mountain, one of these ridges, runs parallel to Bald Eagle Creek on the south side of the city. Upstream of the confluence with Bald Eagle Creek, the West Branch Susquehanna River drains part of the Allegheny Plateau, a region of dissected highlands (also called the “Deep Valleys Section”) generally north of the city. The geologic formations in the southeastern part of the city are mostly limestone, while those to the north and west consist mostly of siltstone and shale. Large parts of the city are flat, but slopes rise to the west, and very steep slopes are found along the river, on the university campus, and along Pennsylvania Route 120 as it approaches U.S. Route 220.

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Lock Haven is in zone Dfa, meaning a humid continental climate with hot or very warm summers. The average temperature here in January is 28 °F (−2 °C), and in July it is 73 °F (23 °C). Between 1888 and 1996, the highest recorded temperature for the city was 106 °F (41 °C) in 1936, and the lowest recorded temperature was −22 °F (−30 °C) in 1912. The average wettest month is June. Between 1926 and 1977, the mean annual precipitation was approximately 39 inches (990 mm), and the number of days each year with precipitation of 0.1 inches (2.5 mm) or more was 77. Annual snowfall amounts between 1888 and 1996 varied from 0 in several years to about 65 inches (170 cm) in 1942. The maximum recorded snowfall in a single month was 38 inches (97 cm) in April 1894.

See also

Map of Pennsylvania State and its subdivision:- Adams

- Allegheny

- Armstrong

- Beaver

- Bedford

- Berks

- Blair

- Bradford

- Bucks

- Butler

- Cambria

- Cameron

- Carbon

- Centre

- Chester

- Clarion

- Clearfield

- Clinton

- Columbia

- Crawford

- Cumberland

- Dauphin

- Delaware

- Elk

- Erie

- Fayette

- Forest

- Franklin

- Fulton

- Greene

- Huntingdon

- Indiana

- Jefferson

- Juniata

- Lackawanna

- Lancaster

- Lawrence

- Lebanon

- Lehigh

- Luzerne

- Lycoming

- Mc Kean

- Mercer

- Mifflin

- Monroe

- Montgomery

- Montour

- Northampton

- Northumberland

- Perry

- Philadelphia

- Pike

- Potter

- Schuylkill

- Snyder

- Somerset

- Sullivan

- Susquehanna

- Tioga

- Union

- Venango

- Warren

- Washington

- Wayne

- Westmoreland

- Wyoming

- York

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming