Cleveland is the county seat of and largest city in Bradley County, Tennessee, United States. The population was 47,356 at the 2020 census. It is the principal city of the Cleveland metropolitan area, Tennessee (consisting of Bradley and neighboring Polk County), which is included in the Chattanooga–Cleveland–Dalton, TN–GA–AL Combined Statistical Area.

Cleveland is the sixteenth-largest city in Tennessee and has the fifth-largest industrial economy, having thirteen Fortune 500 manufacturers.

| Name: | Cleveland city |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 25 |

| LSAD Description: | city (suffix) |

| State: | Tennessee |

| County: | Bradley County |

| Founded: | 1835 |

| Incorporated: | 1842 |

| Elevation: | 860 ft (260 m) |

| Total Area: | 30.87 sq mi (79.96 km²) |

| Land Area: | 30.86 sq mi (79.94 km²) |

| Water Area: | 0.01 sq mi (0.02 km²) |

| Total Population: | 47,356 |

| Population Density: | 1,534.34/sq mi (592.41/km²) |

| Area code: | 423 |

| FIPS code: | 4715400 |

| GNISfeature ID: | 1280705 |

| Website: | www.clevelandtn.gov |

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

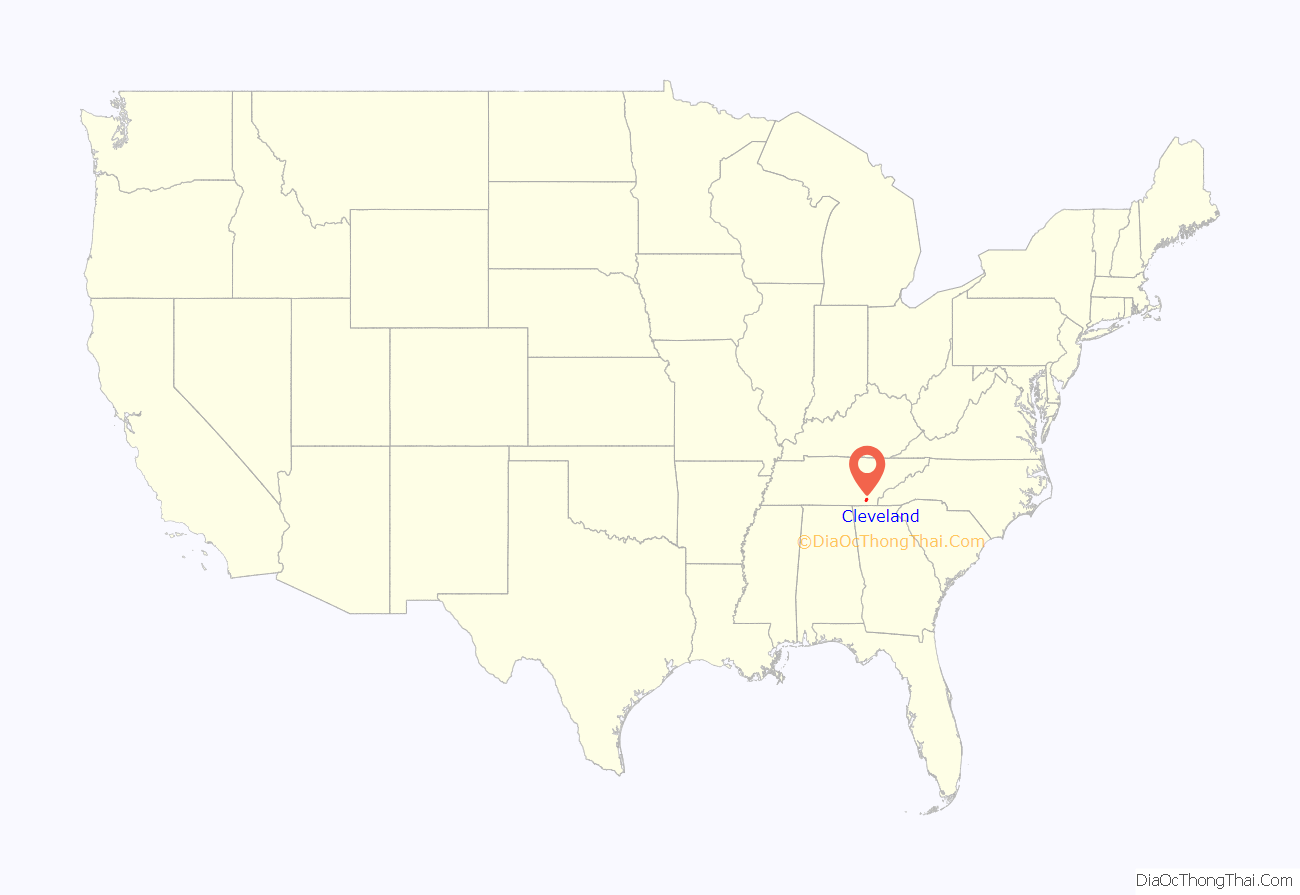

Cleveland location map. Where is Cleveland city?

History

Early history

For thousands of years before European encounter, this area was occupied by succeeding cultures of indigenous peoples. Peoples of the South Appalachian Mississippian culture, beginning about 900-1000 CE, established numerous villages along the river valleys and tributaries. In the more influential villages, they built a single, large earthen platform mound, sometimes surmounted by a temple or elite residence, which was an expression of their religious and political system.

This area was later part of a large territory occupied by the Cherokee Nation, an Iroquoian-speaking people believed to have migrated south from the Great Lakes area, where other Iroquoian tribes arose. Their public architecture was known as the townhouse, a large structure designed for the community to gather together. In some cases, these were built on top of existing mounds; in others the townhouse would front on a broad plaza. Their territory encompassed areas of Western North Carolina, western South Carolina, southeastern Tennessee, northeastern Georgia, and northern Alabama.

The first Europeans to reach the area now occupied by Cleveland and Bradley County were most likely a 1540 expedition through the interior led by Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto. Based on their chronicles, they are believed to have camped along Candies Creek in the western part of present-day Cleveland on June 2, 1540. They encountered some chiefdoms of the Mississippian culture in other areas of South and North Carolina, Tennessee and Georgia. Some writers have suggested that the de Soto expedition was preceded by a party of Welshmen, but there is no supporting evidence and historians consider this unlikely.

During and after the American Revolutionary War, more European Americans entered this area seeking land. They came into increasing conflict with the Cherokee, who occupied this territory. The Cherokee had tolerated traders but resisted settlers who tried to take over their territory and competed for resources.

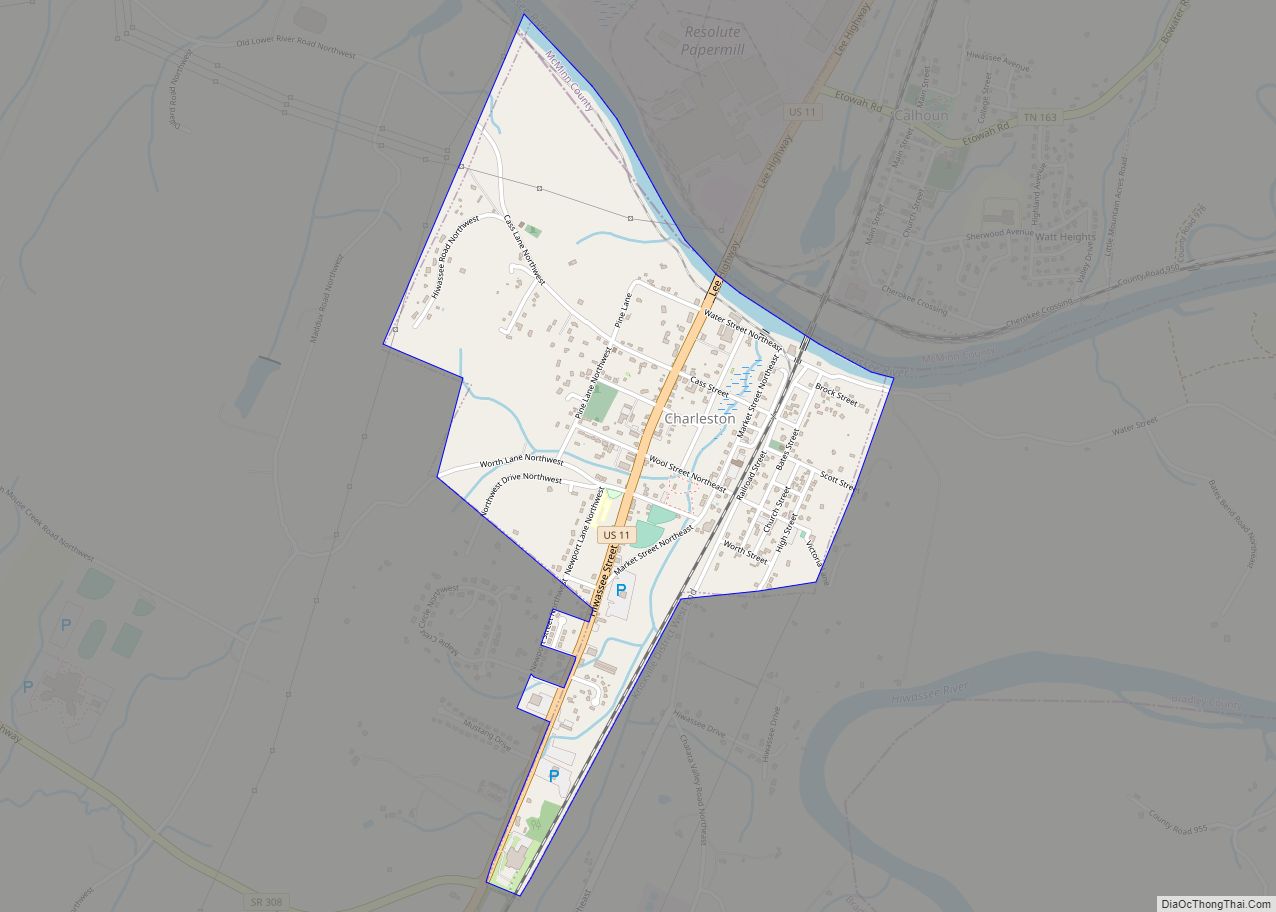

Because of being defeated in repeated attacks by Americans, in 1819 the Cherokee ceded the land directly north of present-day Bradley County (and north of the Hiwassee River) to the U.S. government in the Calhoun Treaty. In 1821 the Cherokee Agency— the official liaison between the U.S. government and the Cherokee Nation— was moved to the south bank of the Hiwassee River in present-day Charleston, a few miles north of what is now Cleveland. The Indian agent was Colonel Return J. Meigs.

By the 1830s, white settlers had begun to move rapidly into this area in anticipation of a forced relocation of the Cherokee and other Southeast tribes. Congress had passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, under President Andrew Jackson’s direction. In 1832, the Cherokee moved the seat of their government to the Red Clay Council Grounds in southern Bradley County. Some Cherokee had already moved to the West, where they were known as Old Settlers until reunification of the Nation. It operated there until the Cherokee removal in 1838, part of the larger forced migration of Cherokee to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). This became known as the Trail of Tears. The former Cherokee seat is now preserved within Red Clay State Park.

The removal was initiated by the Treaty of New Echota on December 29, 1835, although the majority of Cherokee leaders had not approved it. In the Spring of 1838, removal operations by the US military began. Headquarters for the removal were established at Fort Cass in Charleston. In preparation, thousands of Cherokees were rounded up and held in internment camps located between Cleveland and Charleston. Two of the largest were at Rattlesnake Springs. Blythe Ferry, about 15 miles (24 km) northwest of Cleveland in Meigs County, was also an important site during the Cherokee removal.

The legislative act on February 10, 1836 that created Bradley County, which was named for Colonel Edward Bradley of Shelby County, Tennessee, authorized the establishment of a county seat. It was to be named “Cleveland” after Colonel Benjamin Cleveland, a commander at the Battle of Kings Mountain during the American Revolution. The legislative body appointed to govern the county was required to meet in nearby Chatata Valley until a site was chosen for the county seat.

By a one-vote majority on May 2, 1836, the commissioners chose “Taylor’s Place,” the home of Andrew Taylor, as the county seat, due largely to the site’s excellent water sources. Taylor, who had married a Cherokee woman and constructed a log cabin on the site next to a spring, had been given a reservation at the site. A permanent settlement had been established there in 1835, and became a favored stopping place for travelers. The other proposed location for the city was a site a few miles to the east, owned by a wealthy Cherokee named Deer-In-The-Water.

Cleveland was formally established as the county seat by the state legislature on January 20, 1838. That year the city was reported to have a population of 400; it was home to two churches (one Presbyterian, the other Methodist), and a private school for boys, the Oak Grove Academy. The city was incorporated on February 4, 1842, and elections for mayor and aldermen were held shortly afterward on April 4 that year.

While the overwhelming majority of early inhabitants of Cleveland earned their living in agriculture, by 1850 the city also had a sizeable number of skilled craftsmen and professional people. On September 5, 1851 the railroad was completed through Cleveland. After copper mining began in the Copper Basin in neighboring Polk County in the 1840s, headquarters for mining operations were established in Cleveland by Julius Eckhardt Raht, a German-born businessman and engineer. Copper was delivered from the basin to Cleveland by wagon, where it was loaded onto trains. The city’s first bank, the Ocoee Bank, was established in 1854.

Civil War

While bitterly divided over the issue of secession on the eve of the Civil War, Cleveland, like Bradley County and most of East Tennessee, voted against Tennessee’s Ordinance of Secession in June 1861. The results of the countywide vote were 1,382 to 507 in favor of remaining in the Union. Bradley County was represented by Richard M. Edwards and J.G. Brown at the 1861 East Tennessee Convention in Greeneville, an unsuccessful attempt to allow East Tennessee to split from the state and remain part of the Union. Cleveland and Bradley County were occupied by the Confederate Army from June 1861 until the fall of 1863. Despite this occupation, locals remained loyal to the Union, and placed a Union flag in the courthouse square in April 1861, where it remained until June 1862, when it was removed by Confederate forces from Mississippi. Confederate forces also seized control of the copper mines in the Ducktown basin and the rolling mill in Cleveland owned by Raht. Throughout the war both Union and Confederate troops would pass through Cleveland en route to other locations, which led to many brief skirmishes in the area. The most deadly event in Bradley County during the Civil War was a train wreck near the Black Fox community, a few miles south of Cleveland, that killed 270 Confederate soldiers.

Some significant Civil War locations in Bradley County include the Henegar House in Charleston, in which both Union and Confederate generals, including William Tecumseh Sherman, used as brief headquarters; the Charleston Cumberland Presbyterian Church, also in Charleston, which was used by Confederate forces as a hospital; and the Blue Springs Encampments and Fortifications in southern Bradley County, where Union troops under the command of General Sherman camped on numerous occasions between October 1863 and the end of the war. Troops under the command of Sherman also reportedly camped in 1863 near Tasso, a few miles northeast of Cleveland, on multiple occasions.

No large-scale battles took place in and around Cleveland, but the city was considered militarily important due to the railroads. On June 30, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln sent a telegram to General Henry W. Halleck, which read, “To take and hold the railroad at or east of Cleveland, Tennessee, I think is as fully as important as the taking and holding of Richmond.” The railroad bridge over the Hiwassee River to the north was among those destroyed by the East Tennessee bridge-burning conspiracy in November 1861.

On November 25, 1863, during the Battle of Missionary Ridge in Chattanooga, a group of 1,500 Union cavalrymen led by Col. Eli Long arrived in Cleveland. Over the next two days they destroyed twelve miles of railroad in the area, burned the railroad bridge over the Hiwassee a second time, and destroyed the copper rolling mill, which Confederate forces had been using to manufacture artillery shells, percussion caps, and other weaponry. This would prove to be a major blow to the entire Confederate army, as approximately 90% of their copper came from the Ducktown mines. The next day Long’s troops were attacked by a group of about 500 Confederate cavalrymen led by Col. John H. Kelly, and quickly retreated to Chattanooga.

The defeat of Confederate forces in Chattanooga resulted in Union troops regaining control of Cleveland and Bradley County by January 1864, and they retained control for the remainder of the war. Within a few days of the Battle of Missionary Ridge and Long’s raid, several Union units, including members of the 9th Indiana Infantry Regiment, arrived in Cleveland. Additional Union troops arrived in the area in the summer of 1864, and between May and October 1864 a Union artillery unit was stationed downtown, with headquarters established at the home of Julius Eckhardt Raht. During this time as many as 20,000 Union troops at a time camped in the fields surrounding the house in preparation for Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign. Union troops also established two forts, Fort McPherson and Fort Sedgewick, located at Hillcrest Memorial Gardens and Fort Hill Cemetery, respectively, on the highest points of the ridge south of downtown. They successfully repelled an attempted raid by Confederate Gen. Joseph Wheeler on August 17, 1864.

Most of the Union troops stationed in Bradley County left in the summer of 1864 as part of the Atlanta campaign. From this point, Confederate sympathizers conducted guerrilla attacks against Unionist families in Cleveland and surrounding areas, continuing until after the war was over. Members of the Army of Tennessee attempted to destroy a passing Union train near Tasso in the spring of 1864, which instead resulted in the destruction of a Confederate train. The Civil War resulted in much damage to Cleveland and Bradley County, and much of the area was left in ruins.

Reconstruction and industrial revolution

Despite the devastation of the Civil War, Cleveland recovered quickly and much more rapidly than many cities in the South. During the 1870s, Cleveland had a growth spurt, and became one of the first cities in Tennessee to begin to develop industry. Raht, who had fled to Cincinnati, Ohio during the Civil War, returned to Cleveland in 1866 and reopened the copper mines. By 1878 it produced a total of 24 million pounds of copper. Numerous factories were also established, including the Hardwick Stove Company in 1879, the Cleveland Woolen Mills in 1880, and the Cleveland Chair Company in 1884. By 1890, this industrialization helped the city support nine physicians, twelve attorneys, eleven general stores, fourteen grocery stores, three drug stores, three hardware stores, six butcher shops, two hatmakers, two hotels, a shoe store, and seven saloons.

Reflecting industrial prosperity, the city’s iconic Craigmiles Hall was constructed in 1878 as an opera house and meeting hall. It is regarded as the city’s most famous landmark and is one of Tennessee’s most photographed buildings. Behind Craigmiles Hall is a reconstructed bandstand, first built in 1920. The reconstruction was built in 2005 by the Allan Jones Foundation, based on the 1920 blueprints.

The city failed to renew its charter in 1879, with the result that it disincorporated on January 1, 1880. Residents worked to reincorporate the city, and on March 15, 1882, they voted overwhelmingly in favor of recharter. The first city elections under the new charter took place on May 20, 1882. Public amenities were developed in the late 19th century: A mule-drawn trolley system was founded in 1886, and the city received telephone service in 1888. In 1895 the city received electricity and public water. During this period, Cleveland’s population more than doubled, from 1,812 in 1880 to 3,643 in 1900. Many of the buildings in today’s downtown area, now designated as the Cleveland Commercial Historic District, as well as those in the nearby Ocoee Street and Centenary Avenue historic districts, were constructed between 1880 and 1915.

20th century

In 1911 the local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy erected a monument at the intersection of Ocoee, Broad, and 8th streets. This monument was reportedly the first of its kind in East Tennessee. In 1914, the Grand Army of the Republic placed a monument in honor of Union soldiers from Bradley County in Fort Hill Cemetery.

In 1918, the Church of God, a Christian denomination headquartered in Cleveland, established a Bible school that would develop as Lee University. Cleveland’s Chamber of Commerce was established in 1925. On March 21, 1931, the city’s form of government was changed from mayor-aldermen to city commission.

Bob Jones College, a non-denominational Christian college, relocated to Cleveland in 1933 from Panama City, Florida, where it remained until 1947, when it moved to Greenville, South Carolina. The Reverend Billy Graham attended Bob Jones College in Cleveland for one year beginning in 1936.

Following World War II, several major industries located to the area, and the city entered a period of rapid industrial and economic growth as part of the Post–World War II economic expansion. Major factories constructed in the city during this time included American Uniform Company in 1949, Peerless Woolen Mills in 1955, Mallory Battery in 1961, Olin Corporation near Charleston in 1962, and Bendix Corporation in 1964, as well as a Bowater paper mill in nearby Calhoun in 1954. Despite this massive growth in employment, many African American residents of Cleveland and Bradley County moved away as part of the Second Great Migration, and the number of blacks in Cleveland actually declined between 1940 and 1970, while the city’s overall population nearly doubled during this time. During this time and afterwards, Cleveland became one of the largest manufacturing hubs in the Southeastern United States, and this economic expansion continued into the 21st century, with additional major factories locating to the area in the 1970s and 1980s.

In 1966 the Church of God of Prophecy, based in Cleveland, established Tomlinson College north of town, which remained in operation until 1992, when it closed. That same year Cleveland High School was established and schools in Cleveland and Bradley County were integrated. Cleveland State Community College was established in 1967.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the city gained a national reputation for the crime of odometer fraud after 40 people in Bradley County, including multiple owners of car dealerships, were sent to federal prison for the crime. Cleveland was the subject of a November 1983 60 Minutes episode about this crime. The city came to be known as the “Odometer Rollback Capital of the World” to some.

Beginning in the 1950s, the city began to gradually expand to the north as a result of most residential and industrial growth taking place there, but prior to 1987, the city limits of Cleveland did not extend west of Candies Creek Ridge. In 1988, the city began annexing large numbers of adjacent neighborhoods and industrial areas north, northeast, and northwest of the city. These major annexations continued until the late 1990s, and led to the city’s land area increasing in size from approximately 18 square miles in 1989 to about 29.5 square miles in 2000. As a result of this growth, the downtown business district is now geographically located in the southern part of the city.

Recent history

In 1993, Cleveland voters approved a referendum changing the city’s form of government from a city commission to a council-manager government.

Cleveland officially adopted the nickname “The City with Spirit” in 2012. In 2018 voters approved a referendum allowing for package liquor stores to be located within the city. In 2020, the city completed construction of a public park at the site of Taylor Spring, where the first settlement that became Cleveland was founded.

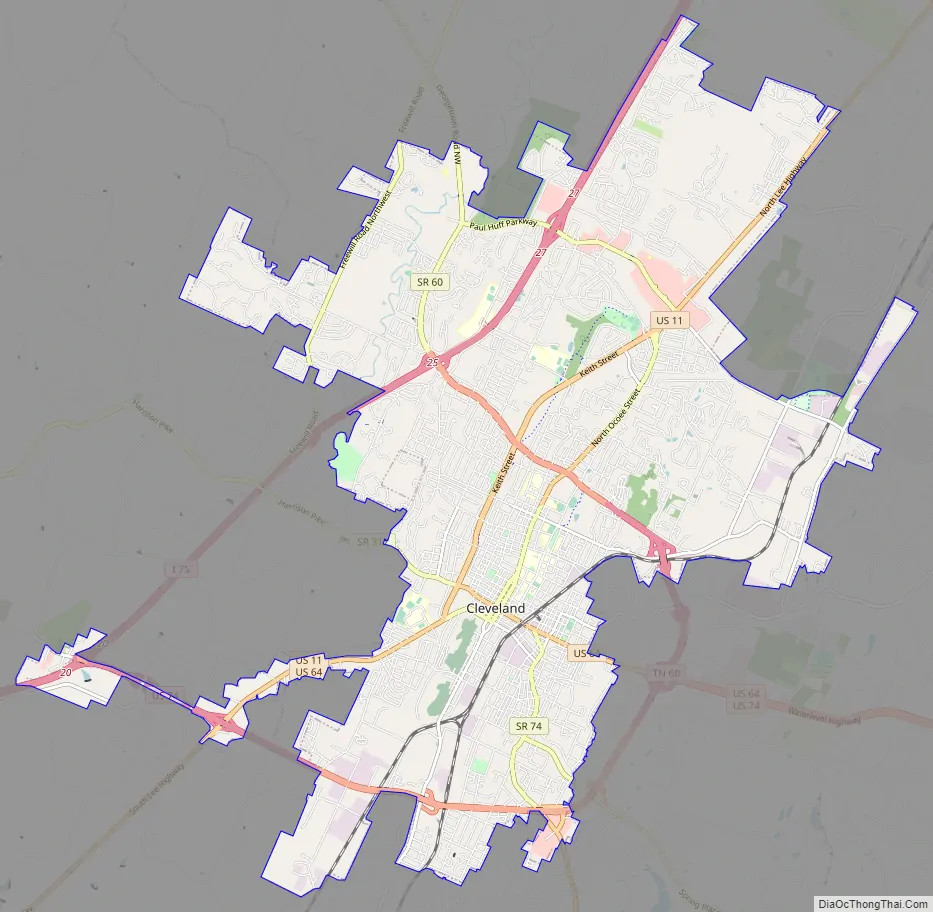

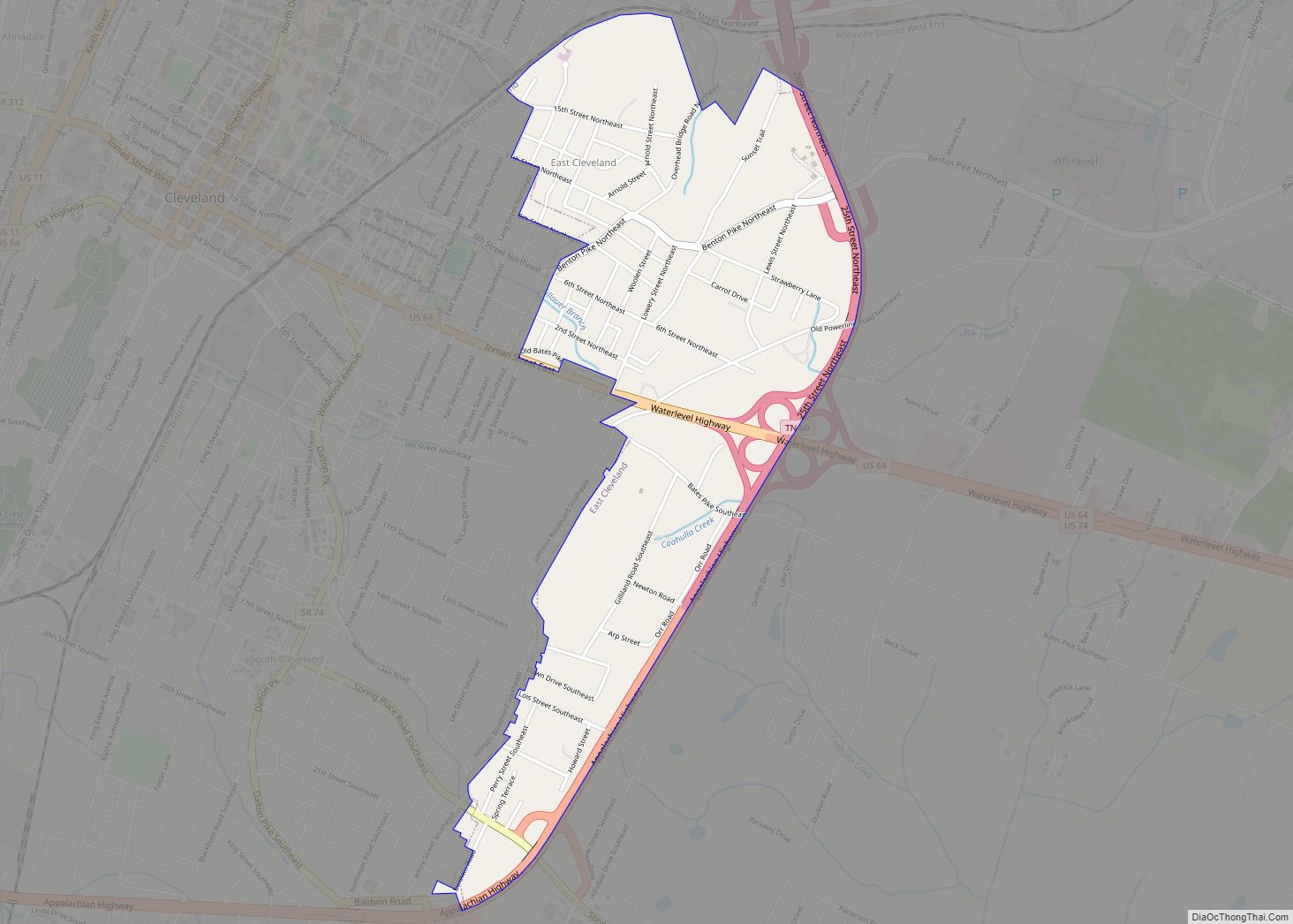

Cleveland Road Map

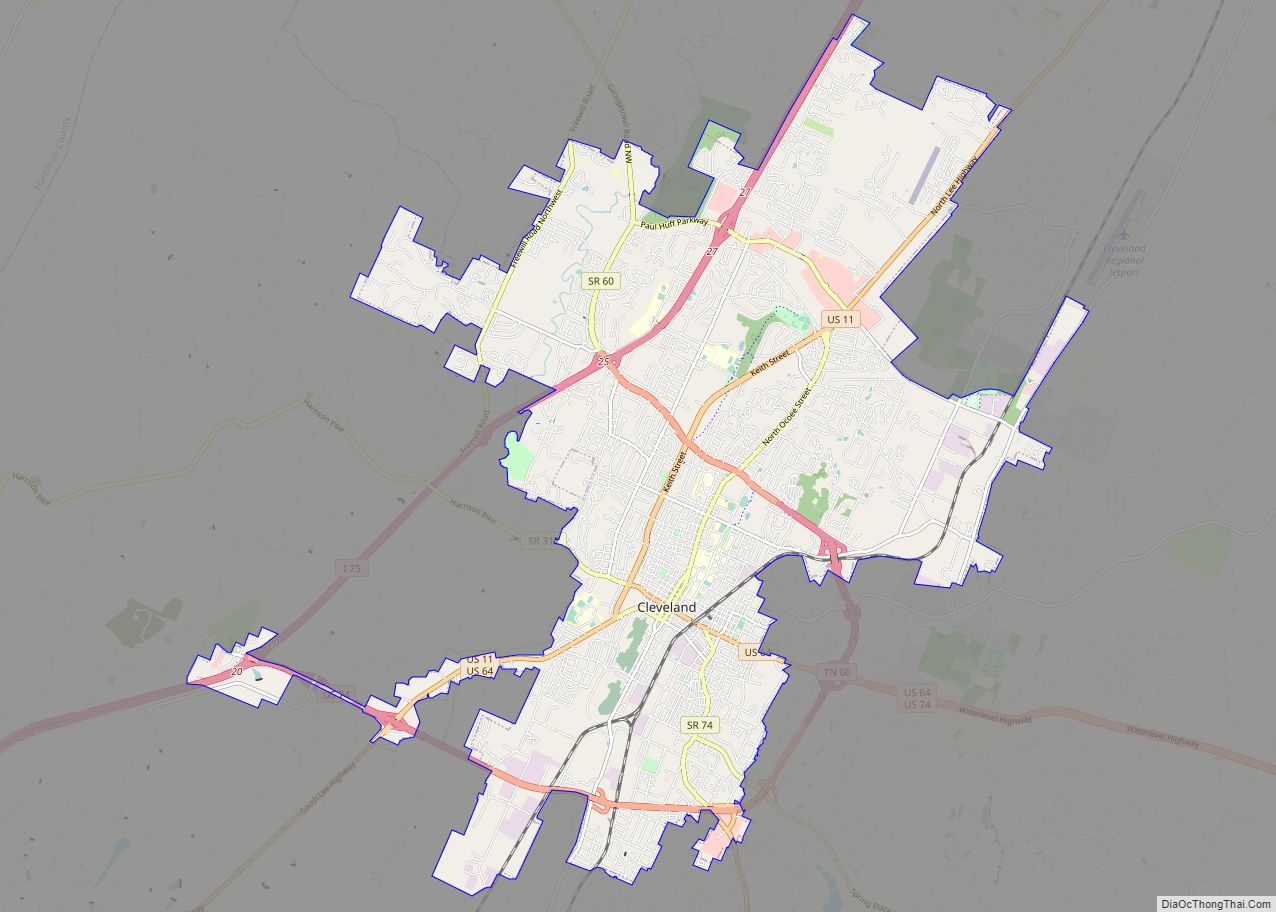

Cleveland city Satellite Map

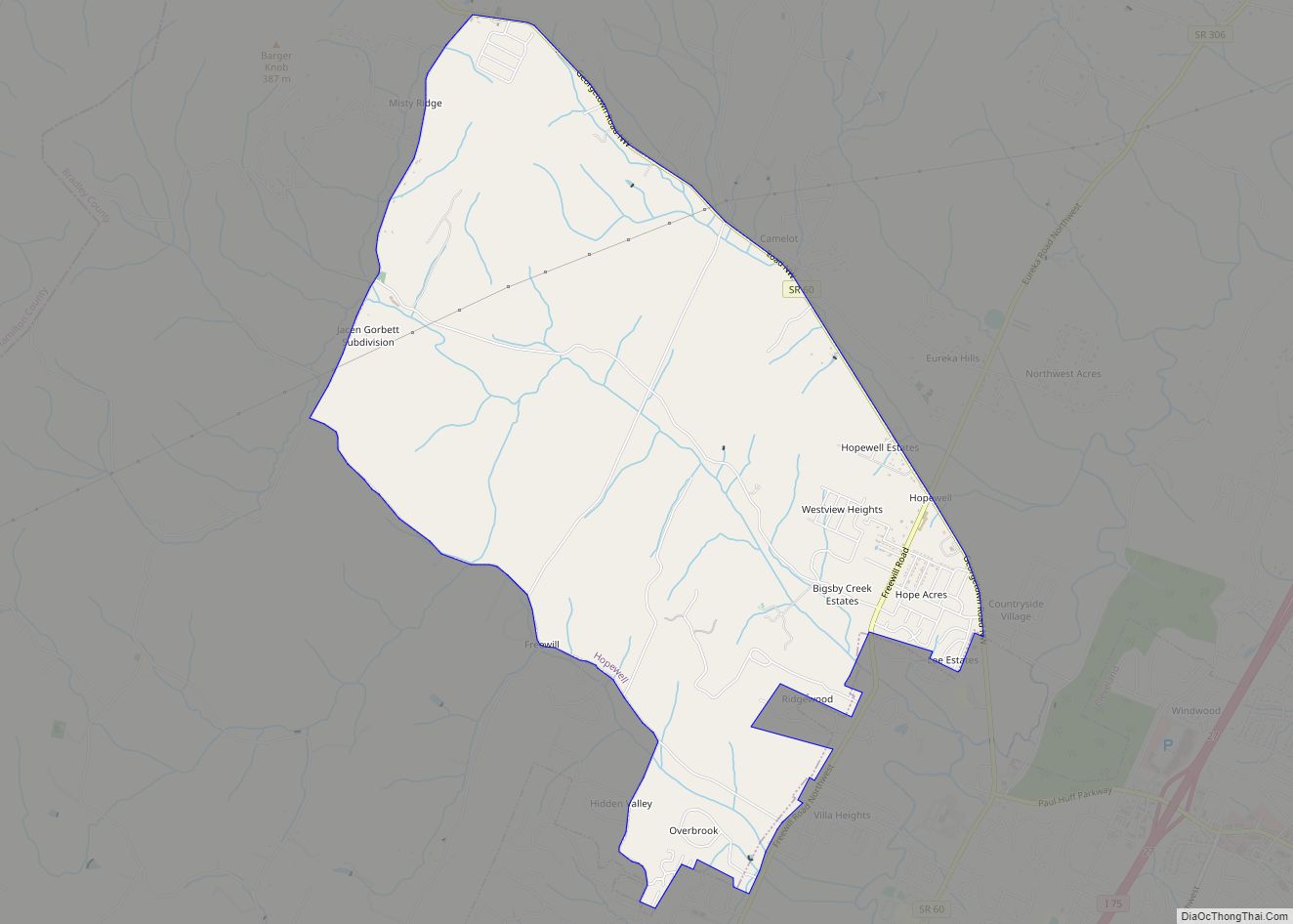

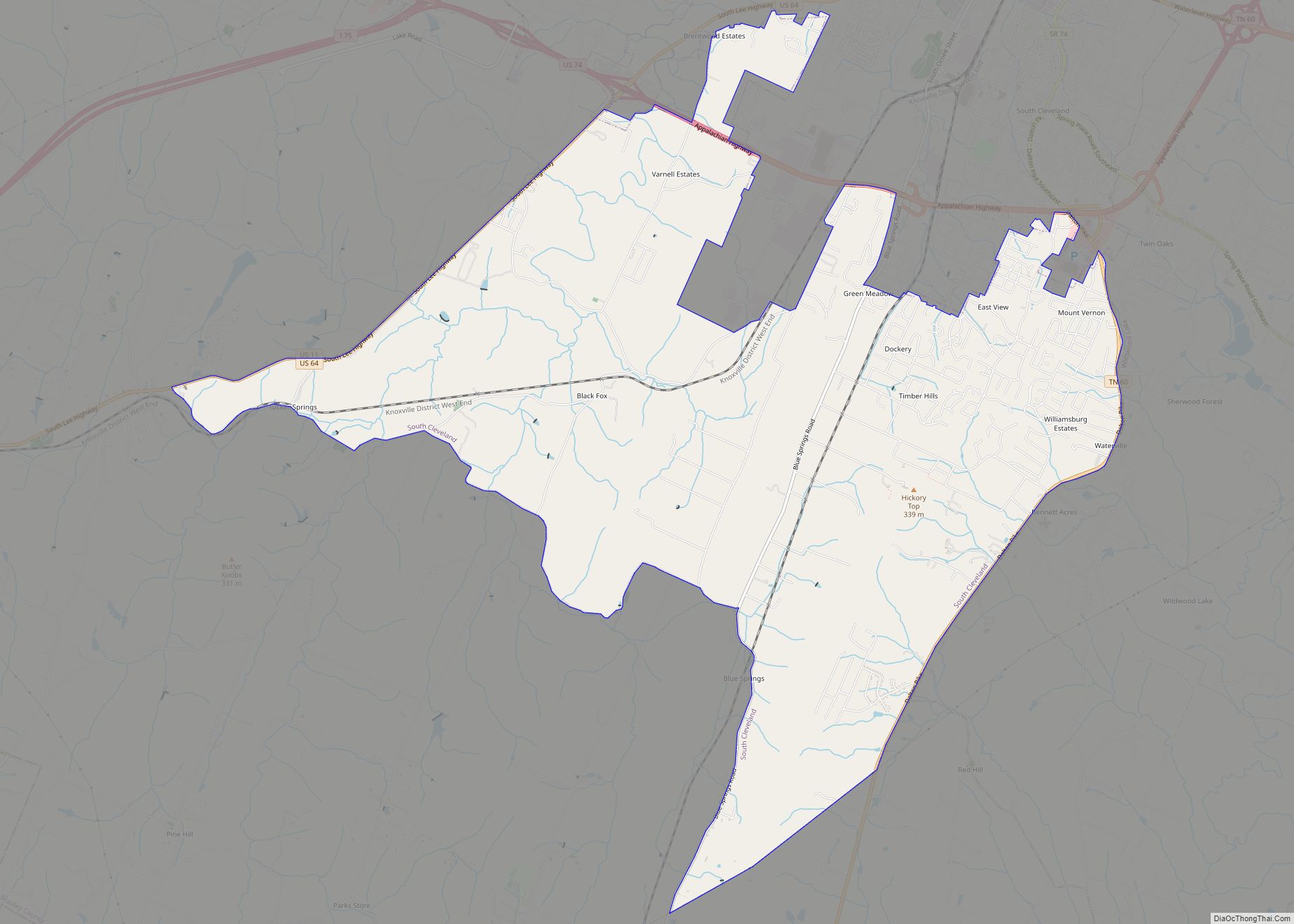

Geography

Cleveland is located in southeast Tennessee in the center of Bradley County in the Great Appalachian Valley, situated among a series of low hills and ridges roughly 15 miles (24 km) west of the Blue Ridge Mountains and 15 miles (24 km) east of the Chickamauga Lake impoundment of the Tennessee River. The Hiwassee River, which flows down out of the mountains and forms the northern boundary of Bradley County, empties into the Tennessee a few miles northwest of Cleveland. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city had a total land area of 26.9 square miles (69.7 km) in 2010.

The area’s terrain is made up of parallel ridges, including Candies Creek Ridge (also called Clingan Ridge), Mouse Creek/Lead Mine Ridge, and Blue Springs Ridge, which are extensions of the Appalachian Mountains (specifically part of the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians) that run approximately north-northeast through the area. Mouse Creek and Blue Springs Ridge have significantly lower elevations within the city of Cleveland than elsewhere in Bradley County, which historically made the area easier to settle. Several streams run in the valleys between the ridges including Candies Creek, located west of Clingan Ridge, and South Mouse Creek, between Mouse Creek and Lead Mine Ridge. Elevations in the city range from just under 700 feet (210 m) to nearly 1,200 feet (370 m). The Tennessee Valley Divide, the boundary of the Tennessee Valley and Mobile River drainage basins, is located on the southern and eastern fringes of the city, and has prevented the city limits from expanding beyond this point in most locations.

Downtown Cleveland, which roughly coexists with the Cleveland Commercial Historic District, encompasses the business district and consists of private businesses and government office buildings including the Bradley County Courthouse and Courthouse Annex, Cleveland Municipal Building, Cleveland Police and Fire department headquarters, and various other government buildings, primarily the offices of city and county departments. The surrounding residential areas, including the Stuart Heights, Ocoee Street, Centenary Avenue, and Annadale neighborhoods, are sometimes considered part of downtown Cleveland. Northern Cleveland has developed as the location for most of the city’s retail shops and private interests. In addition, it is a major residential division, made up of Burlington Heights, Fairview, and Sequoia Grove neighborhoods, and a few major industries. A large industrial area is also located in the northeastern part of the city. The western part of the city is almost entirely residential. Much of it is an extension of the city limits westward to encompass populous middle to upper-class neighborhoods including Hopewell Estates and Rolling Hills. East and South Cleveland consist of lower class residential and industrial areas. People living in East Cleveland tend to be less privileged.

Neighborhoods

Several neighborhoods and communities are located within the city. These include:

- Annadale

- Burlington Heights

- North Cleveland

- Windwood

- Fairview

- Sequoia Grove

- Hopewell (partial)

- Centenary Avenue

- Ocoee Street

- Brentwood Estates

- 20th Street NE/Parker Street District

- Blythe Oldfield

- Rolling Hills

- Laurel Ridge

Climate

Since 1908, 28 tornadoes have been documented in the Cleveland area, seven of which struck on April 27, 2011.

See also

Map of Tennessee State and its subdivision:- Anderson

- Bedford

- Benton

- Bledsoe

- Blount

- Bradley

- Campbell

- Cannon

- Carroll

- Carter

- Cheatham

- Chester

- Claiborne

- Clay

- Cocke

- Coffee

- Crockett

- Cumberland

- Davidson

- Decatur

- DeKalb

- Dickson

- Dyer

- Fayette

- Fentress

- Franklin

- Gibson

- Giles

- Grainger

- Greene

- Grundy

- Hamblen

- Hamilton

- Hancock

- Hardeman

- Hardin

- Hawkins

- Haywood

- Henderson

- Henry

- Hickman

- Houston

- Humphreys

- Jackson

- Jefferson

- Johnson

- Knox

- Lake

- Lauderdale

- Lawrence

- Lewis

- Lincoln

- Loudon

- Macon

- Madison

- Marion

- Marshall

- Maury

- McMinn

- McNairy

- Meigs

- Monroe

- Montgomery

- Moore

- Morgan

- Obion

- Overton

- Perry

- Pickett

- Polk

- Putnam

- Rhea

- Roane

- Robertson

- Rutherford

- Scott

- Sequatchie

- Sevier

- Shelby

- Smith

- Stewart

- Sullivan

- Sumner

- Tipton

- Trousdale

- Unicoi

- Union

- Van Buren

- Warren

- Washington

- Wayne

- Weakley

- White

- Williamson

- Wilson

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming