Greeneville is a town in and the county seat of Greene County, Tennessee, United States. The population as of the 2020 census was 15,479. The town was named in honor of Revolutionary War hero Nathanael Greene, and it is the second oldest town in Tennessee. It is the only town with this spelling in the United States, although there are numerous U.S. towns named Greenville. The town was the capital of the short-lived State of Franklin in the 18th-century history of East Tennessee.

Greeneville is known as the town where United States President Andrew Johnson began his political career when elected from his trade as a tailor. He and his family lived there for most of his adult years. It was an area of strong abolitionist and Unionist views and yeoman farmers, an environment that influenced Johnson’s outlook.

The Greeneville Historic District was established in 1974.

The U.S. Navy Los Angeles-class submarine USS Greeneville was named in honor of the town.

Greeneville is part of the Johnson City–Kingsport– Bristol TN-VA Combined Statistical Area – commonly known as the “Tri-Cities” region.

| Name: | Greeneville town |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 43 |

| LSAD Description: | town (suffix) |

| State: | Tennessee |

| County: | Greene County |

| Founded: | 1783 |

| Incorporated: | 1795 |

| Elevation: | 1,519 ft (463 m) |

| Land Area: | 17.00 sq mi (44.02 km²) |

| Water Area: | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km²) |

| Population Density: | 910.69/sq mi (351.63/km²) |

| Area code: | 423 |

| FIPS code: | 4730980 |

| Website: | www.greenevilletn.gov |

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

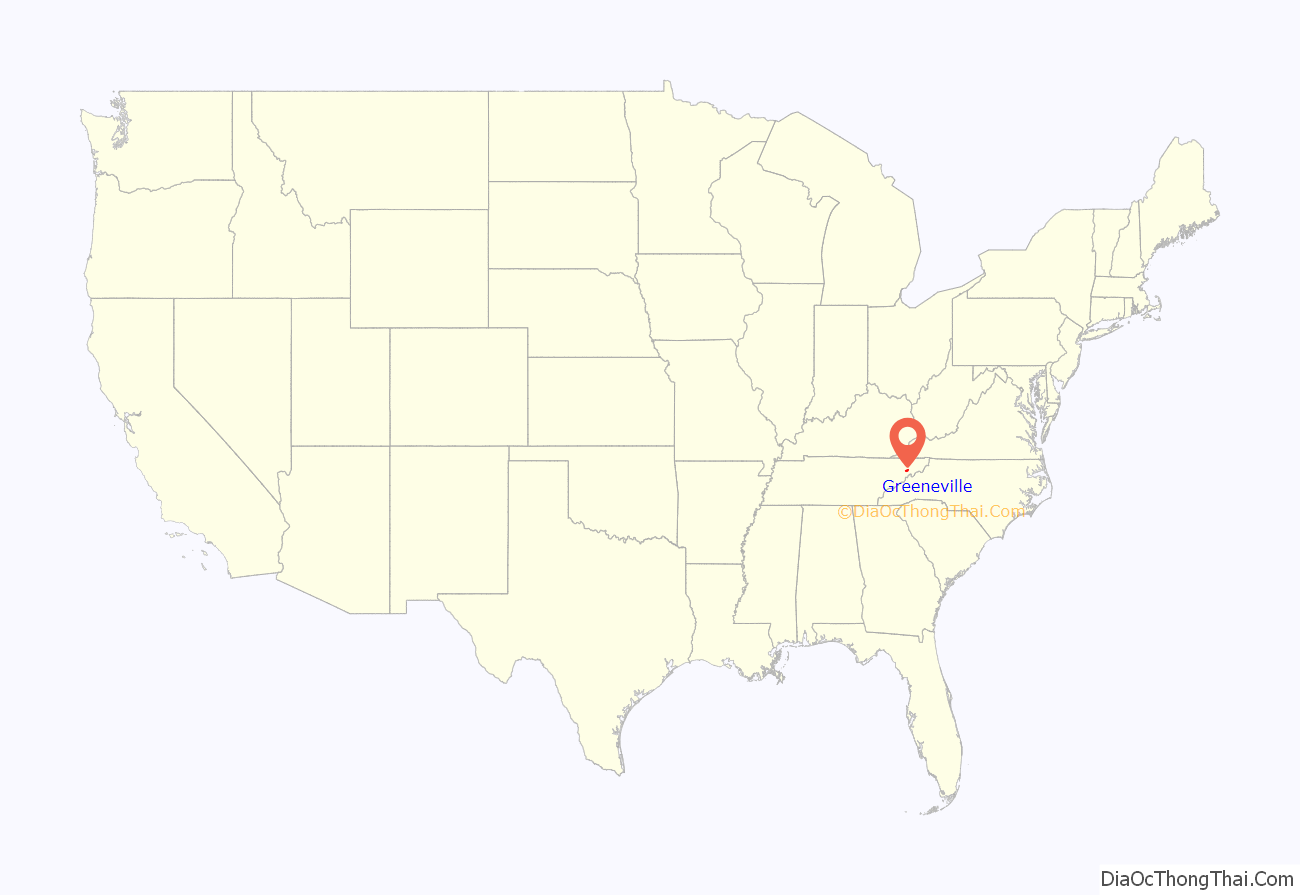

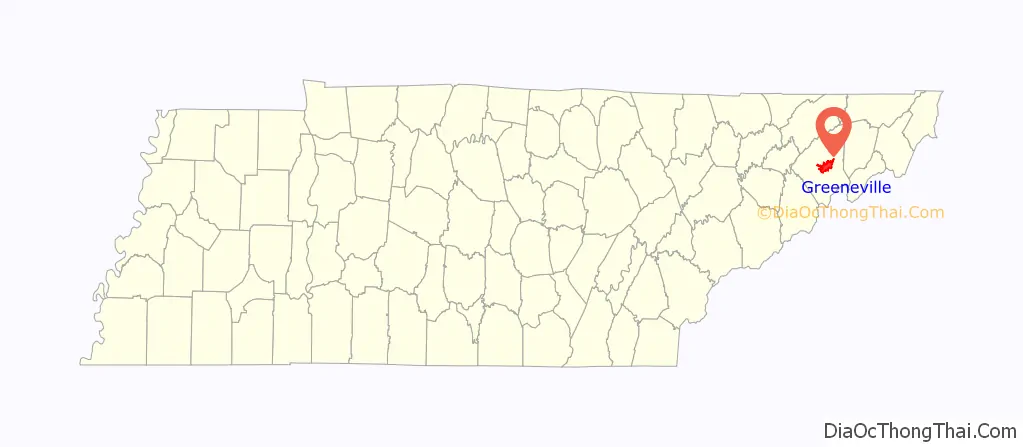

Greeneville location map. Where is Greeneville town?

History

Early history

Native Americans were hunting and camping in the Nolichucky Valley as early as the Paleo-Indian period (c. 10,000 B.C.). A substantial Woodland period (1000 B.C. – 1000 A.D.) village existed at the Nolichucky’s confluence with Big Limestone Creek (now part of Davy Crockett Birthplace State Park). By the time the first Euro-American settlers arrived in the area in the late 18th century, the Cherokee claimed the valley as part of their hunting grounds. The Great Indian Warpath passed just northwest of modern Greeneville, and the townsite is believed to have once been the juncture of two lesser Native American trails.

The permanent European settlement of Greene County began in 1772. Jacob Brown, a North Carolina merchant, leased a large stretch of land from the Cherokee, located between the upper Lick Creek watershed and the Nolichucky River, in what is now the northeastern corner of the county. The “Nolichucky Settlement” initially aligned itself with the Watauga Association as part of Washington County, North Carolina. After voting irregularities in a local election, however, an early Nolichucky settler named Daniel Kennedy (1750–1802) led a movement to form a separate county, which was granted in 1783.

The county was named after Nathanael Greene, reflecting the loyalties of the numerous Revolutionary War veterans who settled in the Nolichucky Valley, especially from Pennsylvania and Virginia. The first county court sessions were held at the home of Robert Kerr, who lived at “Big Spring” (near the center of modern Greeneville). Kerr donated 50 acres (0.20 km) for the establishment of the county seat, most of which was located in the area currently bounded by Irish, College, Church, and Summer streets. “Greeneville” was officially recognized as a town in 1786.

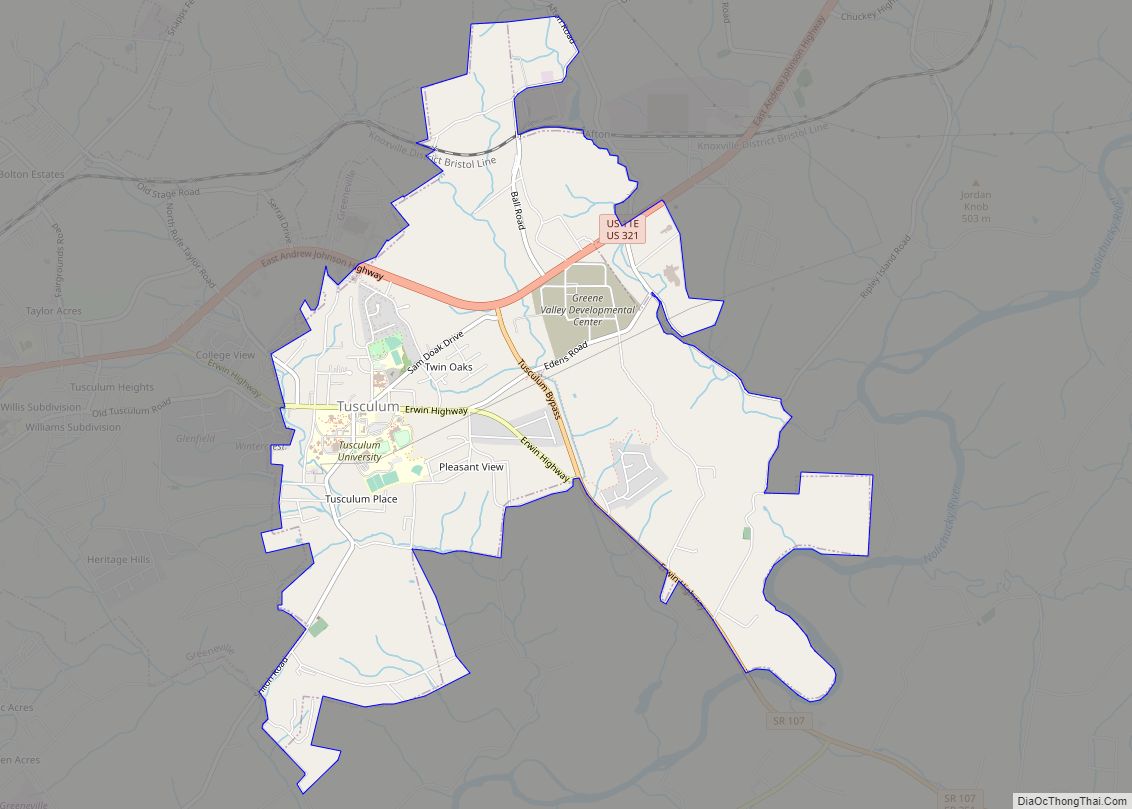

State of Franklin

In 1784, North Carolina attempted to resolve its debts by giving the U.S. Congress its lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, including Greene County, abandoning responsibility for the area to the federal government. In response, delegates from Greene and neighboring counties convened at Jonesborough and resolved to break away from North Carolina and establish an independent state. The delegates agreed to meet again later that year to form a constitution, which was rejected when presented to the general delegation in December. Reverend Samuel Houston (not to be confused with the later governor of Tennessee and Texas) had presented a draft constitution that restricted the election of lawyers and other professionals. Houston’s draft met staunch opposition, especially from Reverend Hezekiah Balch (1741–1810) (who was later instrumental in the creation of Tusculum College). John Sevier was elected governor, and other executive offices were filled.

A petition for statehood for what would have become known as the State of Franklin (named in honor of Benjamin Franklin) was drawn at the delegates session in May 1785. The delegates submitted a petition for statehood to Congress, which failed to gain the requisite votes needed for admission to the Union. The first state legislature of Franklin met in December 1785 in a crude log courthouse in Greeneville, which had been named the capital city the previous August. During this session, the delegates finally approved a constitution that was based on, and quite similar to, the North Carolina state constitution. However, the Franklin movement began to collapse soon thereafter, with North Carolina reasserting its control of the area the following spring.

In 1897, at the Tennessee Centennial Exposition in Nashville, a log house that had been moved from Greeneville was displayed as the capitol where the State of Franklin’s delegates met in the 1780s. There is, however, nothing to verify that this building was the actual capitol. In the 1960s, the capitol was reconstructed, based largely on the dimensions given in historian J. G. M. Ramsey’s Annals of Tennessee.

Greeneville and the abolitionist movement

Greene County, like much of East Tennessee, was home to a strong abolitionist movement in the early 19th century. This movement was likely influenced by the relatively large numbers of Quakers who migrated to the region from Pennsylvania in the 1790s. The Quakers considered slavery to be in violation of Biblical Scripture and were active in the region’s abolitionist movement throughout the antebellum period. One such Quaker was Elihu Embree (1782–1820), who published the nation’s first abolitionist newspaper, The Emancipator, at nearby Jonesborough.

When Embree’s untimely death in 1820 effectively ended publication of The Emancipator, several of Embree’s supporters turned to Ohio abolitionist Benjamin Lundy, who had started publication of his own antislavery newspaper, The Genius of Universal Emancipation, in 1821. Anticipating that a southern-based abolitionist movement would be more effective, Lundy purchased Embree’s printing press and moved to Greeneville in 1822. Lundy remained in Greeneville for two years before moving to Baltimore. He would later prove influential in the career of William Lloyd Garrison, whom he hired as an associate editor in 1829.

Greenevillians involved in the abolitionist movement included Hezekiah Balch, who freed his slaves at the Greene County Courthouse in 1807. Samuel Doak, the founder of Tusculum College, followed in 1818. Valentine Sevier (1780–1854), a nephew of John Sevier who served as Greene County Court Clerk, freed his slaves in the 1830s and offered to pay for their passage to Liberia, which had been formed as a colony for freed slaves. Francis McCorkle, the pastor of Greeneville’s Presbyterian Church, was a leading member of the Manumission Society of Tennessee.

Civil War

In June 1861, on the eve of the Civil War, thirty counties of the pro-Union East Tennessee Convention met in Greeneville to discuss strategy after state voters had elected to join the Confederate States of America. The convention sought to create a separate state in East Tennessee that would remain with the United States. The state government in Nashville rejected the convention’s request, however, and East Tennessee was occupied by Confederate forces shortly thereafter. Thomas Dickens Arnold, a Greeneville resident and former congressman who attended the convention, advocated the use of violent force to allow East Tennessee to break away from Tennessee, and taunted other members of the convention who advocated a more peaceful set of resolutions.

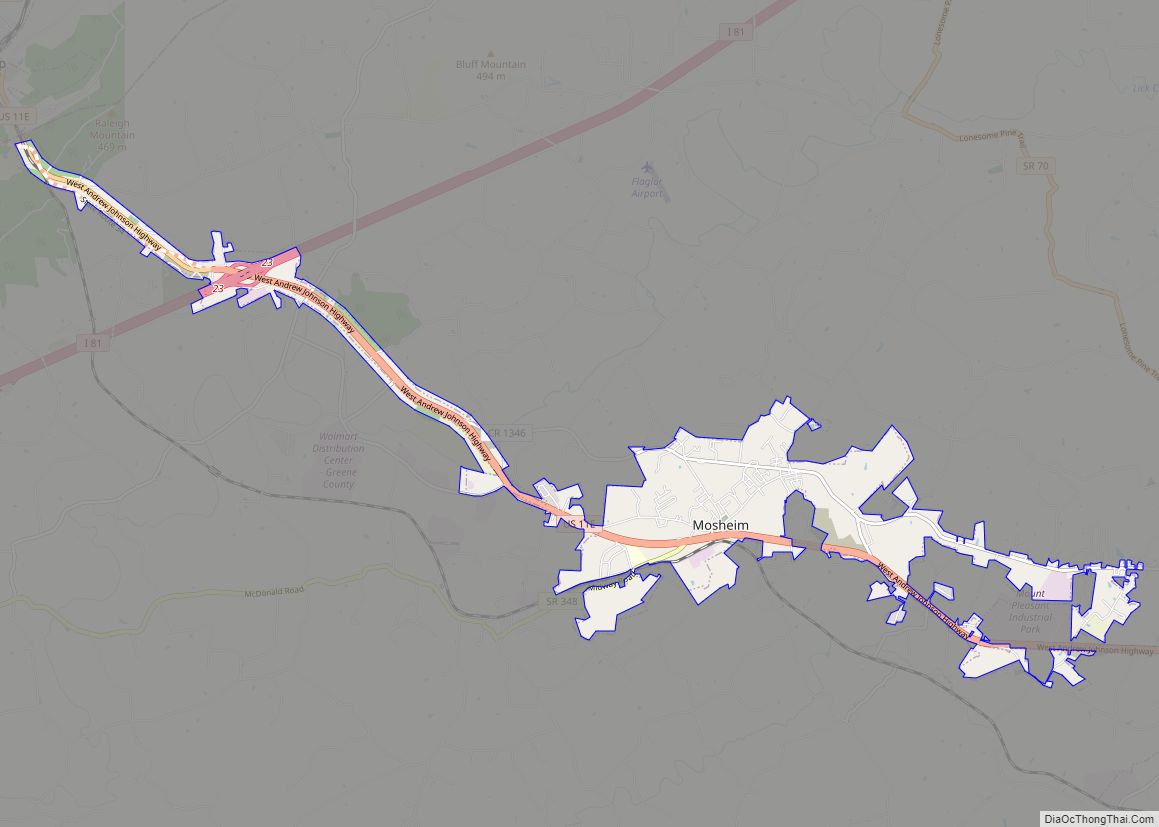

Several conspirators involved in the pro-Union East Tennessee bridge burnings lived near what is now Mosheim, and managed to destroy the railroad bridge over Lick Creek in western Greene County on the night of November 8, 1861. Two of the conspirators, Jacob Hensie and Henry Fry, were executed in Greeneville on November 30, 1861.

A portion of James Longstreet’s army wintered in Greeneville following the failed Siege of Knoxville in late 1863. Confederate general John Hunt Morgan was killed in Greeneville during a raid by Union soldiers led by Alvan Cullem Gillem on September 4, 1864.

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson, the 17th President of the United States, spent much of his active life in Greeneville. In 1826, Johnson arrived in Greeneville after fleeing an apprenticeship in Raleigh. Johnson chose to remain in Greeneville after learning that the town’s tailor was planning to retire. Johnson purchased the tailor shop, which he moved from Main Street to its present location at the corner of Depot and College streets. Johnson married a local girl, Eliza McCardle, in 1827. The two were married by Mordecai Lincoln (1778–1851), who was Greene County’s Justice of the Peace. He was a cousin of Abraham Lincoln, under whom Johnson would serve as vice president.

In the late 1820s, a local artisan named Blackstone McDannel often stopped by Johnson’s tailor shop to debate issues of the day, especially the Indian Removal, which Johnson opposed. Johnson and McDannel decided to debate the issue publicly. The interest sparked by this debate led Johnson, McDannel, and several others to form a local debate society. The experience and influence Johnson gained in debating local issues helped him get elected to the Greeneville City Council in 1829. He was elected mayor of Greeneville in 1834, although he resigned after just a few months in office to pursue a position in the Tennessee state legislature, which he attained the following year. As Johnson rose through the ranks of political office in state and national government, he used his influence to help Greeneville constituents obtain government positions, among them his long-time supporter, Sam Milligan, who was appointed to the Court of Claims in Washington, D.C.

Whilst Andrew Johnson was away from home, during his vice-presidency, both Union and Confederate armies often used his home as a place to stay and rest during their travel. Soldiers left graffiti on the walls of Johnson’s home. Confederate soldiers left notes on the walls expressing their displeasure, to put it delicately, of Johnson. Evidence of this can still be seen at the Andrew Johnson home. Andrew Johnson had to almost completely renovate his home after he returned home from Washington, D.C.

The Andrew Johnson National Historic Site, located in Greeneville, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1963. Contributing properties include Johnson’s tailor shop at the corner of Depot and College streets. The site also maintains Johnson’s house on Main Street and the Andrew Johnson National Cemetery (atop Monument Hill to the south). A replica of Johnson’s birth home and a life-size statue of Johnson have been placed across the street from the visitor center and tailor shop.

Indian Wars

Buffalo Soldiers originally were members of the 10th Cavalry Regiment of the United States Army, formed on September 21, 1866, at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. This nickname was given to the Black Cavalry by Native American tribes who fought in the Indian Wars. The term eventually became synonymous with all of the African-American regiments formed in 1866. Greeneville was home to at least four men who bravely served the country as “Buffalo Soldiers”.

George Clem School

In 1887, with assistance from the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, the George Clem School was organized as Greeneville College. In 1932, the Greeneville Board of Education leased the property to provide public education for Negroes. Three years later, George Clem was appointed principal. Consisting of grades one through ten, the school was renamed Greeneville College High School. In 1937, the 11th grade was added. A year later, the school became an accredited four-year school. In 1939, the city purchased the school and renamed in the George Clem School. A decade later, the original building was demolished and the present building was erected in 1950. The school closed in 1965 when the public schools desegregated, and it became the location of the Greeneville City Schools Central Office. The George Clem School is often overlooked when talking about Greeneville history. Topics such as Sam Doak, the death of General Morgan, and Andrew Johnson are often the focal points when learning about Greeneville. The George Clem School is something the town should promote and be proud of. This history shows the accomplishments of the black community in Greeneville through the years. There is now a non profit organization in Greeneville by the name of George Clem Multicultural Alliance that helps honor the history of the school. The George Clem Multicultural Alliance is a non-profit 501(c)(3), public benefit, & exclusively charitable organization dedicated to supporting civic pride & cultural diversity awareness through various means within Wesley Heights community, and Greeneville/Greene County at large

From 1947 to 2005, Magnavox—an electronics manufacturer best known for its television sets—operated its main three facilities in Greeneville. Magnavox was at one time the largest employer of Greeneville, employing more than 5,000 workers. Eight years after the first plant opened, Magnavox workers voted to form a union through the IBEW. In 1974, the facilities and the Magnavox company were acquired by the electronics giant Philips. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, the Greeneville facility saw a fluctuation and drops in employment. In 1997, Phillips sold its facilities to Knoxville-based company Five Rivers Electronic Innovations. In 2005, Five Rivers closed the former Magnavox plant after declaring bankruptcy. Before its shuttering, the Five Rivers facility was the site of the last television manufactured in the United States, which is now on display in the Greeneville-Greene County History Museum.

2011 tornado outbreak

On April 27, 2011, the rural community of Camp Creek south of Greeneville was severely affected by an EF3 tornado in the 2011 Super Outbreak. Six people were killed and 220 were injured by the tornado that either damaged or destroyed over 175 homes. Two hours later, Horse Creek, southeast of Greeneville, was also hit by an EF3 tornado, with the path travelling alongside and later crossing the earlier Camp Creek event as it moved into Washington County. Another 60-65 homes were either damaged or destroyed, and around 25 farms sustained heavy structural damage. Two more people were killed by that tornado, with an estimated 70 more being injured. A total of seven were killed in Greene County, with an eighth fatality in Washington County.

Downtown revitalization

In 2018, town officials, with the cooperation of a development and urban design firm, began efforts towards the redevelopment of the central business district of Greeneville. The project is projected to operate in several phases, projects proposed include: a farmer’s market pavilion, a greenway along Richland Creek, an alley park, improved access for pedestrians and cyclists, parking garages, and the conversion of Depot Street into a street fair area.

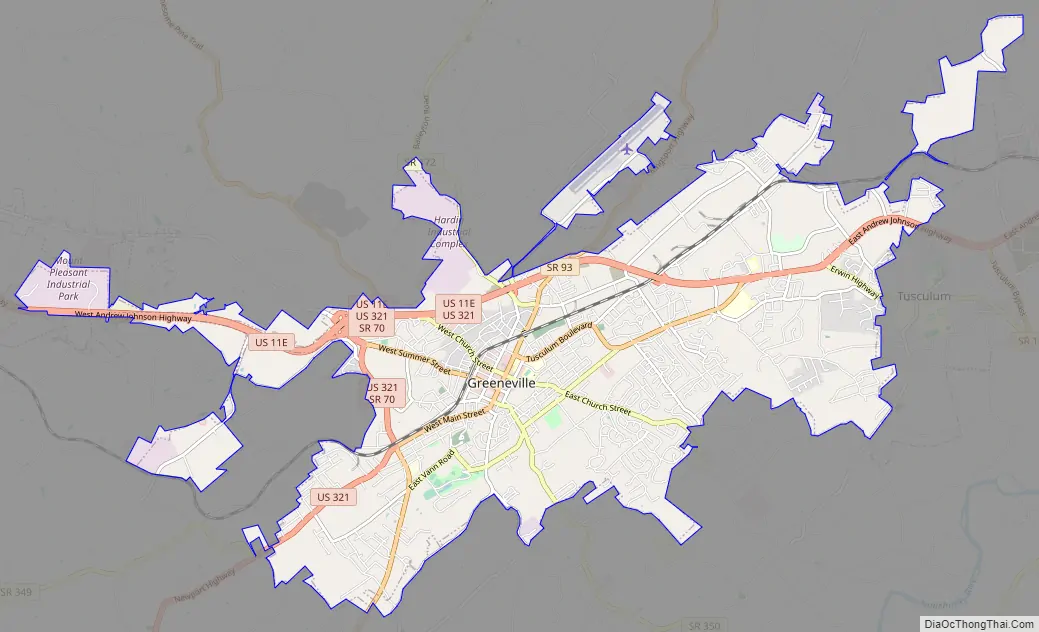

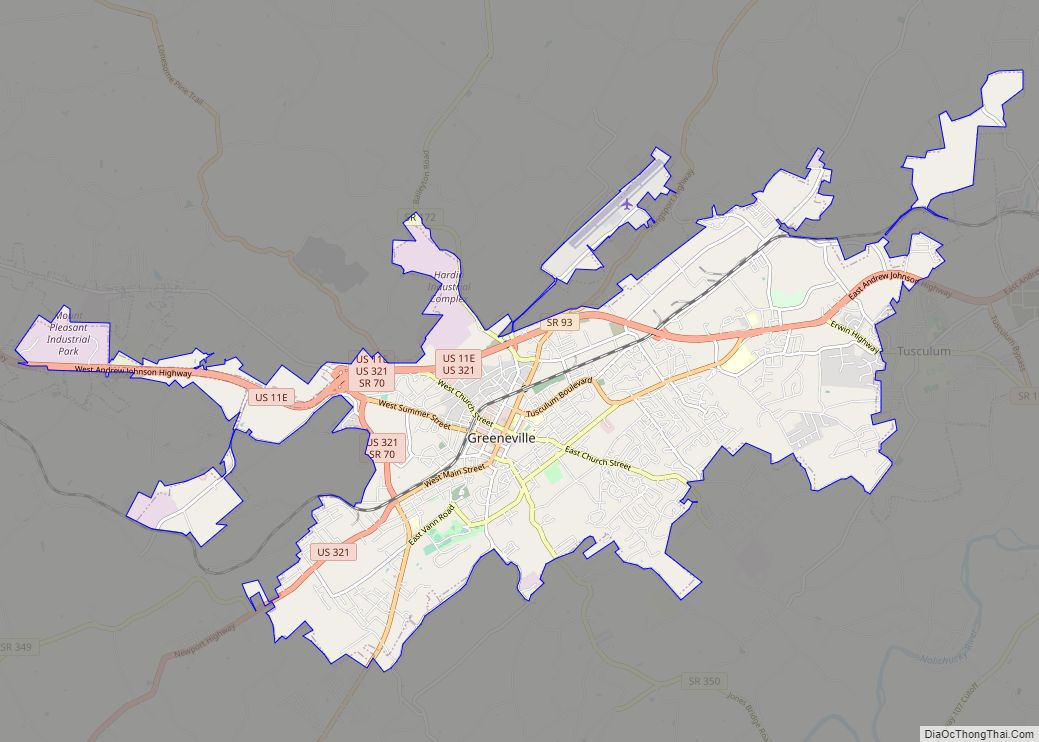

Greeneville Road Map

Greeneville city Satellite Map

Geography

Greeneville is located at 36°10′6″N 82°49′21″W / 36.16833°N 82.82250°W / 36.16833; -82.82250 (36.168240, -82.822474). It lies in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. These hills are part of the Appalachian Ridge-and-Valley Province, which is characterized by fertile river valleys flanked by narrow, elongate ridges. Greeneville is located roughly halfway between Bays Mountain to the northwest and the Bald Mountains— part of the main Appalachian crest— to the southeast. The valley in which Greeneville is situated is part of the watershed of the Nolichucky River, which passes a few miles south of the town.

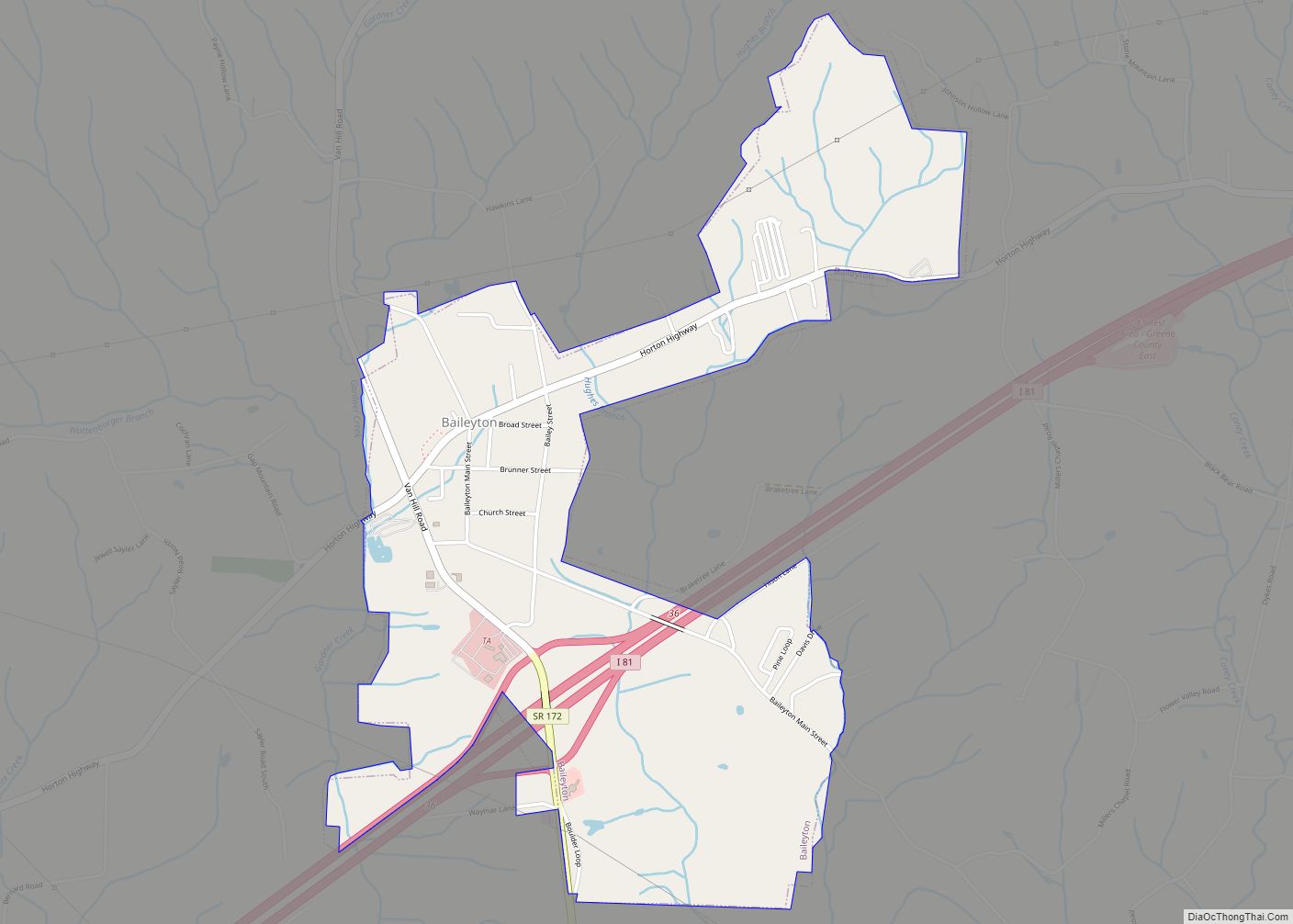

Several federal and state highways now intersect in Greeneville, as they were built to follow old roads and trails. U.S. Route 321 follows Main Street through the center of the town and connects Greeneville to Newport to the southwest. U.S. Route 11E (Andrew Johnson Highway), which connects Greeneville with Morristown to the west, intersects U.S. 321 in Greeneville and the merged highway proceeds northeast to Johnson City. Tennessee State Route 107, which also follows Main Street and Andrew Johnson Hwy, Greeneville to Erwin to the east and to the Del Rio area to the south. Tennessee State Route 70 (Lonesome Pine Trail) connects Greeneville with Interstate 81, and Rogersville to the north and Asheville, North Carolina to the south. Tennessee State Route 172 (Baileyton Road) connects Greeneville with Interstate 81 and Baileyton to the north.

Tennessee State Route 93 (Kingsport Highway) connects Greeneville to Interstate 81, Fall Branch and Kingsport to the north.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 17.01 square miles (44.1 km), all land.

Climate

Neighborhoods

- Buckingham Heights

- Cherrydale

- Oak Hills

- Windy Hills

- Harrison Hills

See also

Map of Tennessee State and its subdivision:- Anderson

- Bedford

- Benton

- Bledsoe

- Blount

- Bradley

- Campbell

- Cannon

- Carroll

- Carter

- Cheatham

- Chester

- Claiborne

- Clay

- Cocke

- Coffee

- Crockett

- Cumberland

- Davidson

- Decatur

- DeKalb

- Dickson

- Dyer

- Fayette

- Fentress

- Franklin

- Gibson

- Giles

- Grainger

- Greene

- Grundy

- Hamblen

- Hamilton

- Hancock

- Hardeman

- Hardin

- Hawkins

- Haywood

- Henderson

- Henry

- Hickman

- Houston

- Humphreys

- Jackson

- Jefferson

- Johnson

- Knox

- Lake

- Lauderdale

- Lawrence

- Lewis

- Lincoln

- Loudon

- Macon

- Madison

- Marion

- Marshall

- Maury

- McMinn

- McNairy

- Meigs

- Monroe

- Montgomery

- Moore

- Morgan

- Obion

- Overton

- Perry

- Pickett

- Polk

- Putnam

- Rhea

- Roane

- Robertson

- Rutherford

- Scott

- Sequatchie

- Sevier

- Shelby

- Smith

- Stewart

- Sullivan

- Sumner

- Tipton

- Trousdale

- Unicoi

- Union

- Van Buren

- Warren

- Washington

- Wayne

- Weakley

- White

- Williamson

- Wilson

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming