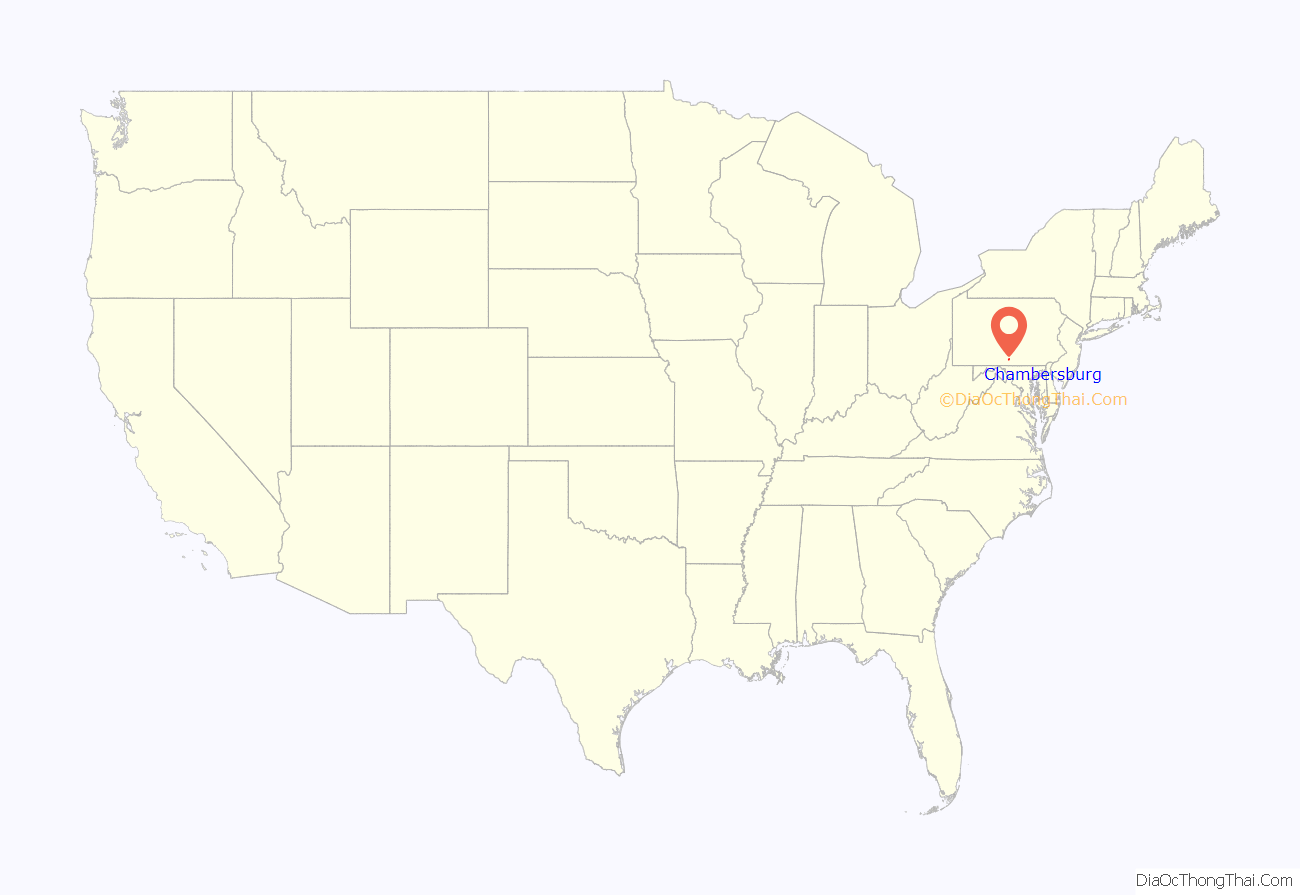

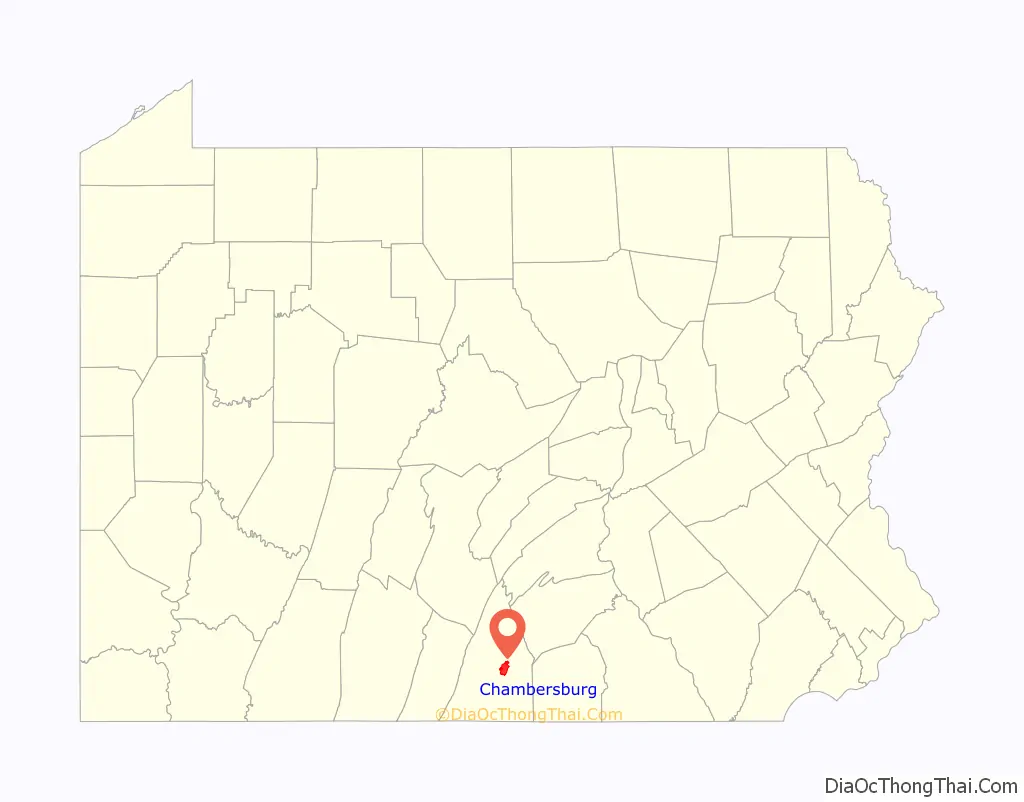

Chambersburg is a borough in and the county seat of Franklin County, in the South Central region of Pennsylvania, United States. It is in the Cumberland Valley, which is part of the Great Appalachian Valley, and 13 miles (21 km) north of Maryland and the Mason-Dixon line and 52 miles (84 km) southwest of Harrisburg, the state capital. According to the United States Census Bureau, Chambersburg’s 2020 population was 21,903. When combined with the surrounding Greene, Hamilton, and Guilford Townships, the population of Greater Chambersburg is 52,273 people. The Chambersburg, PA Metropolitan Statistical Area includes surrounding Franklin County, and in 2010 included 149,618 people.

According to the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development, Chambersburg Borough is the thirteenth-largest municipality in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the largest borough, as measured by fiscal size (2016). Chambersburg Borough is organized under the Pennsylvania Borough Code and is not a home-rule municipality.

Chambersburg’s settlement began in 1730, when water mills were built at Conococheague Creek and Falling Spring Creek. The town developed on both sides of these creeks. Its history includes episodes relating to the French and Indian War, the Whiskey Rebellion, John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, and the Civil War. The borough was the only major northern community burned down by Confederate forces during the war. Residents charged the Confederates with war crimes.

Chambersburg is served by the Lincoln Highway, U.S. 30, between McConnellsburg and Gettysburg. U.S. 11, the Molly Pitcher Highway, passes through it between Shippensburg, Pennsylvania, and Hagerstown, Maryland. Interstate 81 skirts the borough to its east. The town lies approximately midpoint on US Route 30 between Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. The local topography reflects both flatter areas like Philadelphia and mountainous areas like Pittsburgh. Downtown Chambersburg has occasional events such as Food Truck Festival and Apple Fest.

| Name: | Chambersburg borough |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 21 |

| LSAD Description: | borough (suffix) |

| State: | Pennsylvania |

| County: | Franklin County |

| Founded: | 1734 |

| Incorporated: | March 21, 1803 |

| Elevation: | 630 ft (192 m) |

| Land Area: | 6.92 sq mi (17.94 km²) |

| Water Area: | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km²) |

| Population Density: | 3,162.89/sq mi (1,221.23/km²) |

| ZIP code: | 17201, 17202 |

| Area code: | 717 and 223 |

| FIPS code: | 4212536 |

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

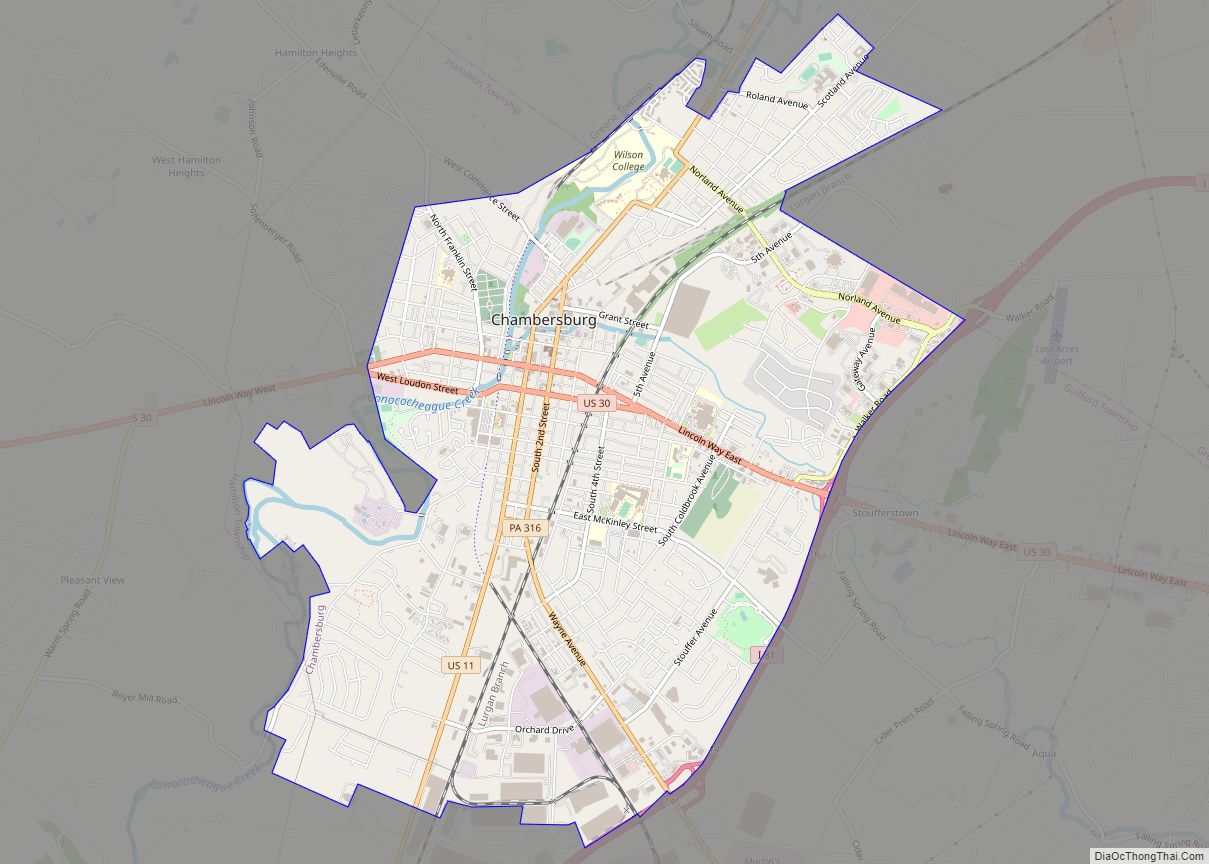

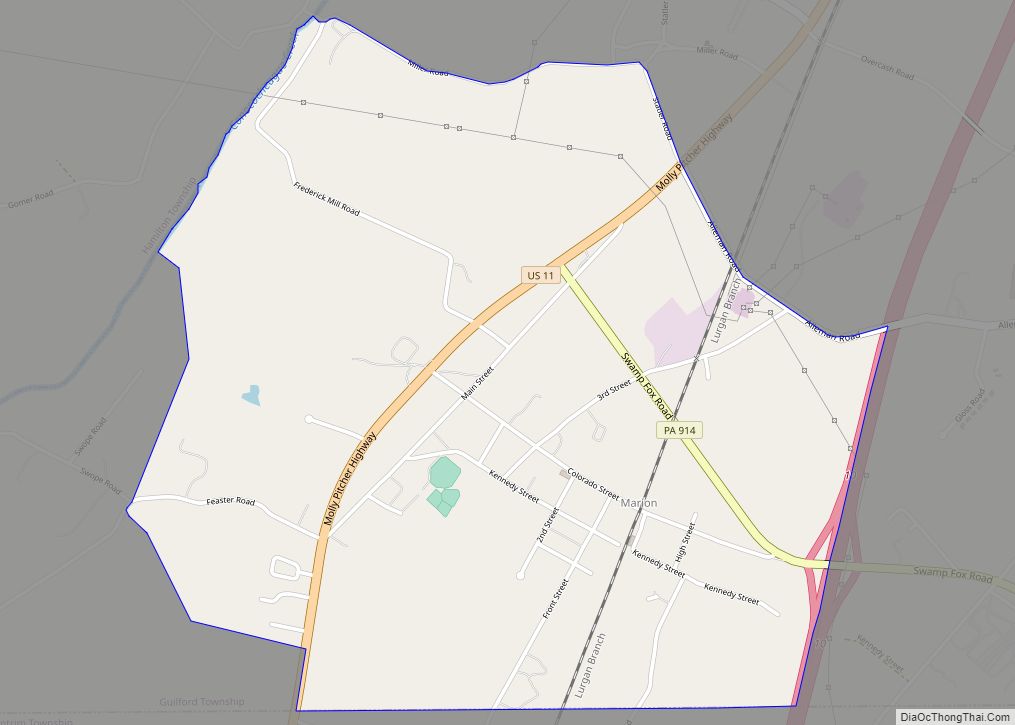

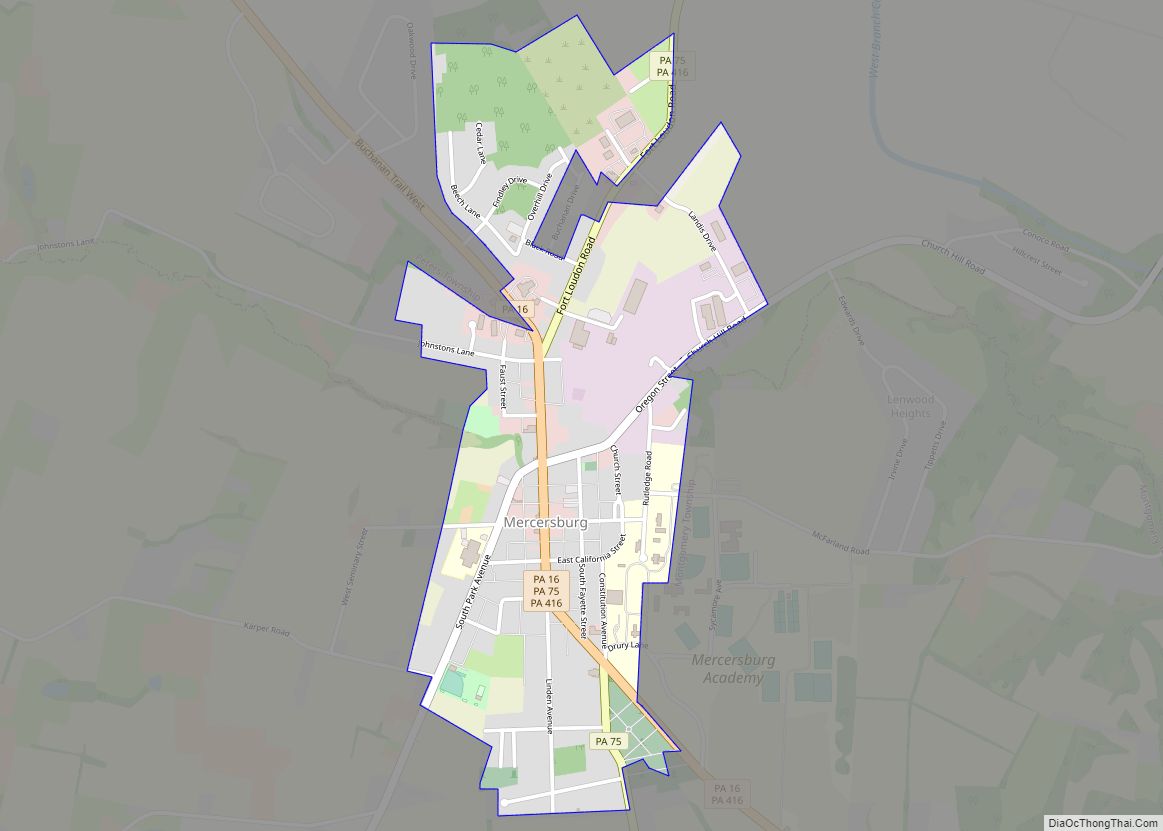

Chambersburg location map. Where is Chambersburg borough?

History

European settlement

Native Americans living or hunting in the area during the 18th century included the six Iroquois tribes of a confederacy known as the Iroquois League or Haudenosaunee, the Lenape, and the Shawnee. The Lenape lived mostly to the east, with the Iroquois to the north, and the Shawnee to the south. Their traders, hunters, and warriors traveled on the north-south route sometimes called the “Virginia path” through the Cumberland Valley, from New York through what became Carlisle and Shippensburg, then through what would become Hagerstown, Maryland, crossing the Potomac River into the Shenandoah Valley.

Benjamin Chambers, a Scots-Irish immigrant, is credited with settling “Falling Spring” in 1730. He built a grist mill and saw mill by a then-26-foot-high (7.9 m) waterfall where Falling Spring Creek joined Conococheague Creek. The creek provided power for the mills, and soon a settlement grew and became known as “Falling Spring.”

On March 30, 1734, Chambers received a “Blunston license” for 400 acres (160 ha), from a representative of the Penn family. European settlement in the area remained of questionable legality until the treaty ending the French and Indian War in 1763, because not all Indian tribes with land claims had signed treaties with the British colonial government.

The Penn family encouraged settlement in the area in order to strengthen its case in a border dispute with the Maryland Colony, which had resulted in hostilities known as Cresap’s War. This dispute was not settled until 1767, with the border survey that resulted in the Mason-Dixon line. Chambers traveled to England to testify in support of Penn’s claims. To maintain peace with the Indians, Penn sometimes arranged for European settlers to be removed from nearby areas. In May 1750, Benjamin Chambers helped remove settlers from the nearby Burnt Cabins, named after an incident.

The area was first classified as part of Chester County, then Lancaster County (as that was created from Chester County’s western area). Then Lancaster County was split, with its western portion renamed as Cumberland County; finally another split (this time of Cumberland County) established Franklin County in 1784. (Adams County adjoins it on the east).

The Great Wagon Road connecting Philadelphia with the Shenandoah Valley (and an east-west branch through Hagerstown and Cumberland, Maryland to the Ohio Valley known as Nemacolin’s Path) passed nearby. In 1744, the road was completed through Harris’s Ferry, Carlisle, Shippensburg, and Chambersburg to the Potomac River. In 1748 a local militia was formed for protection against Indians, with Benjamin Chambers named as its colonel.

Chambersburg was still considered frontier during the French and Indian War. Benjamin Chambers built a private stone fort during the war, which was equipped with two 4-pounder cannons. Fighting and troop movements occurred nearby. The area’s population dropped from about 3,000 in 1755 as the war began, to about 300 during the conflict. Most settlers did not return until after 1764 (when the peace treaty was signed between Great Britain and France).

Because Chambers’s fort was otherwise lightly defended, officials attempted to remove the cannons to prevent them from being captured by Indians and used against other forts. However, the attempted removal failed. One of the cannons still remained in 1840, when it was fired to celebrate Independence Day that year.

The Forbes Road and other trails going to Fort Pitt passed nearby as well. The Forbes Road developed into part of the main road connecting Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, and much later into US 30. Chambersburg developed as a trading and transportation hub at the crossroads of Forbes Road and the Great Wagon Road.

Fighting continued in the area after the war. The Enoch Brown school massacre took place during Pontiac’s War, when Native Americans were trying to expel European Americans from the area. The Black Boys rebelled against British troops stationed at Fort Loudon.

The town of Chambersburg was platted or laid out in 1764. Lots were advertised for sale on July 19 in Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette.

The first settlers were Scots-Irish Presbyterians; German Protestants came soon afterward. Relatively few Quakers and English Protestants (who made up a large proportion of early Pennsylvania settlers generally) settled as far west as Chambersburg. However, blacks lived in Chambersburg almost from the settlement’s beginning. Benjamin Chambers owned a black female slave sometime before the French and Indian War and twenty slaves were recorded as taxable property in 1786.

The earliest church was established by Scots-Irish Presbyterians in 1734. Chambers gave the congregation land in 1768, for an annual rent of only a single rose. Later, the First Lutheran Church and Zion Reformed Church both organized in 1780 under similar terms, so these three churches came to be known as the “Rose Rent Churches.” A Catholic community organized in 1785. St. James African Methodist Episcopal Church dates its founding to members purchasing a log cabin from the expanding Catholic congregation in 1811, and the congregation continued and expanded through 1830. The Mt. Moriah First African Baptist Church dates to 1887. The Jewish cemetery dates back to 1840.

1775–1858

In June 1775, soon after the Battle of Lexington, local troops were raised to fight the British in the American Revolution under the command of Benjamin Chambers’s eldest son Captain James Chambers, as part of the 1st Pennsylvania Regiment. These troops were among the first non-New Englanders to join the siege of Boston, arriving on August 7, 1775. James Chambers fought for seven years during the revolution, reaching the rank of Colonel of Continental Army troops on September 26, 1776. His two brothers, William and Benjamin Jr., each served for much of the war and reached the rank of captain. James Chambers commanded local troops at the Battle of Long Island, and at White Plains, Trenton, Princeton, Brandywine, Germantown, and Monmouth. He was part of the rear guard covering the retreat from Brooklyn, and was wounded at the Battle of Brandywine while facing Hessian troops under General Knuphausen at Chadds Ford.

During the Whiskey Rebellion, local citizens raised a liberty pole in support of the rebels, and to protest conscription of soldiers to put down the rebellion. Nevertheless, these citizens were censured in a town meeting and removed the pole the next day. President George Washington, while leading United States troops against the rebels, came through town on the way from Carlisle to Bedford, staying overnight on October 12, 1794. According to tradition, Washington lodged with Dr. Robert Johnson, a surgeon in the Pennsylvania line during the Revolution. This march was one of only two times that a sitting president personally commanded the military in the field. (The other was after President James Madison fled the British occupation of Washington, D.C. during the War of 1812.) After sending the troops toward Pittsburgh from Bedford under General Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, Washington returned through Chambersburg sometime between October 21–26. James Chambers was appointed a Brigadier General of Militia during the Whiskey Rebellion.

Chambersburg was incorporated on March 21, 1803, and declared the County Seat when the State Assembly established a formal government. The first courthouse was John Jack’s tavern on the Diamond (town square) in 1784, with a permanent courthouse built in 1793, and the first county jail built 1795. The “Old Jail” was built in 1818, survived the fire of 1864 and is the oldest jail building in Pennsylvania. It was originally used as the sheriff’s residence and had the longest continuous use of any jail in the state, operating until 1971. Today the Old Jail is a museum and home to the Franklin County – Kittochtinny Historical Society. The county’s gallows still stand in the jail’s courtyard. From 1786 to 1879 there were 5 executions in Franklin County totaling 6 felons- 5 for murder and 1 for rape.

Much of the town’s growth was due to its position as a transportation center, first as the starting point on the Forbes Road to Pittsburgh. The U.S. Congress placed Chambersburg on the Philadelphia-Pittsburgh postal road in 1803. The road was rebuilt as the Chambersburg-Bedford Turnpike in 1811. The Cumberland Valley Railroad was built in 1837 and was the area’s center of economic activity for nearly 100 years. Until the completion of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s main line in 1857, the fastest route from Pittsburgh to Philadelphia was by stagecoach from Pittsburgh to Chambersburg, and then by train to Philadelphia.

Civil War era

By 1859, Chambersburg’s active community of free and enslaved blacks and sympathetic whites had attracted a stop on the Underground Railroad. Several schools taught black children, although such activity was illegal in Virginia and other slave states further south. John Brown stayed in an upstairs room at Mary Ritner’s boarding house between June and October, 1859 while preparing for his raid on Harpers Ferry (then in Virginia). Several of his fellow raiders stayed in the house as well, and four of them escaped capture and briefly visited the house after the raid. The house still stands at 225 East King Street. While in Chambersburg, Brown posed as Dr. Isaac Smith, an iron mine developer, and bought, shipped, and stored weapons under the guise of mining equipment.

Brown (using the name John Smith) and John Henry Kagi met with Frederick Douglass and Shields Green at an abandoned quarry outside of town to discuss the raid on August 19. According to Douglass’s account, Brown described the planned raid in detail and Douglass advised him against it. Douglass also provided $10 from a supporter, and had helped Green – a future raider – locate Brown.

During the American Civil War on October 10, 1862, Confederate Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, with 1,800 cavalrymen, raided Chambersburg, destroying $250,000 of railroad property and taking 500 guns, hundreds of horses, and enslaving “eight young colored men and boys.” They failed, however, to accomplish one of the main targets of the raid: to burn the railroad bridge across the Conococheague Creek at Scotland, five miles (8 km) north of town.

During the early days of the 1863 Gettysburg Campaign, a Virginia cavalry brigade under Brig. Gen. Albert G. Jenkins occupied the town and burned several warehouses and Cumberland Valley Railroad structures and the bridge at Scotland. From June 24–28, 1863, much of the Army of Northern Virginia passed through Chambersburg en route to Carlisle and Gettysburg, and General Robert E. Lee established his headquarters at a nearby farm.

The following year, Chambersburg was invaded for a third time, as cavalry, dispatched from the Shenandoah Valley by Jubal Early, arrived. On July 30, 1864, a large portion of the town was burned down by Confederate Brig. Gen. John McCausland for failing to provide a ransom of $500,000 in U.S. currency, or $100,000 in gold. The local bank had sent its reserves out of town for safekeeping. Among the few buildings left standing was the Masonic Temple, which had been guarded under orders by a Confederate member of the Masons. Norland, the home of Republican politician and editor Alexander McClure, was burned although it was well north of the main fire. Early had ordered the ransom as compensation for those residents of the Shenandoah Valley whose homes has been burned by Union Brig.-Gen. David Hunter. He also burned the Virginia Military Institute. According to McCausland report the only death occurred when one of his soldiers was killed in the vicinity of the town after his troops left and no citizens lost their lives. One black Chambersburg resident was burned to death when Confederates set his house on fire and then refused to allow him to leave, trapping him in the flames. Another man was asked by the Confederates if he had ever educated “niggers”; after replying that he had, the Confederates burned his house down. Subsequently, “Remember Chambersburg” became a Union battle cry. The Property damage was $713,294.34 + Personal Property damage was $915,137,24 totaling $1,628,431.58 of which 50% was paid by State approbation, first by an Act of Legislature Feb 15, 1866, $500,000.00 and the second under the Act of Legislation May 27, 1871; under the last named act claiments [numbering 650] each had a certificate for amount of his loss but claims payable only when said claims were paid by the United States Government

John Brown in 1859

Alexander K. McClure

J.E.B. Stuart

Gen. John McCausland

Lieut. Gen. Jubal Early, who ordered Chambersburg burned

Civil War Legacy

Confederate Lieutenant General Jubal Early was accused of war crimes for ordering Chambersburg burned. The actual burning divided two of his cavalry commanders, because when Maryland-born Gen. Joseph “Allegheny” Johnson saw the behavior of Gen. McCausland’s troops in Chambersburg, he refused to participate in a similar burning at Cumberland and Hancock, Maryland not far to the south, so both those towns survived despite likewise not paying ransoms. Union cavalry under Brig. Gen. William W. Averell, although initially misdirected toward Baltimore and thus late to arrive to prevent the atrocities, also pursued the Confederates, who sustained several defeats and lost most of the Shenandoah Valley by November. Furthermore, when the Army of Northern Virginia surrendered on April 9, 1865, Early escaped to Texas by horseback, where he hoped to find a Confederate force still holding out. He proceeded to Mexico, and from there, sailed to Cuba and Canada. Living in Toronto, he wrote his memoir, A Memoir of the Last Year of the War for Independence, in the Confederate States of America, which focused on his Valley Campaign and was published in 1867.

A combination of state and private funding rebuilt Chambersburg. However, many new buildings were erected quickly and not initially built to the original standards. It took more than 30 years to fully restore the town’s housing stock to pre-Civil War standards. As discussed further below, Chambersburg was the site of one of the 69 schools established by Pennsylvania to educate children orphaned by the war, and which remained when all other such were closed decades later. Known as “The Scotland School for Veterans Children” after the 1890s, it remained open until 2010 and graduated more than 10,000 children during its lifetime.

Since people from Chambersburg had relatives on both sides during the war, and the war devastated the town, the town event also became a part of the town’s identity. On July 17, 1878, 15,000 people attended dedication of Memorial Fountain in the town’s center, which honors the Civil War soldiers, and later Chambersburg’s fighters in other wars. A statue of a Union soldier stands next to the fountain, facing south to guard against the return of southern raiders.

To this day, the Civil War burning of Chambersburg remains a part of the town’s historic identity and yearly memorial events are held, especially near July 30.

Chambersburg has also recently been the subject of study on how people have historically perceived and responded to war tragedies.

National Register of Historic Places

The following places in Chambersburg are on the National Register of Historic Places:

Historic images

Colorized photographs taken from a series of 22 postcard views mailed in 1921.

Birds eye view of the borough.

City Hall

King Street Bridge.

View of the “Lincoln Way Arch” on the Diamond.

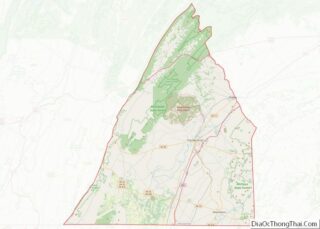

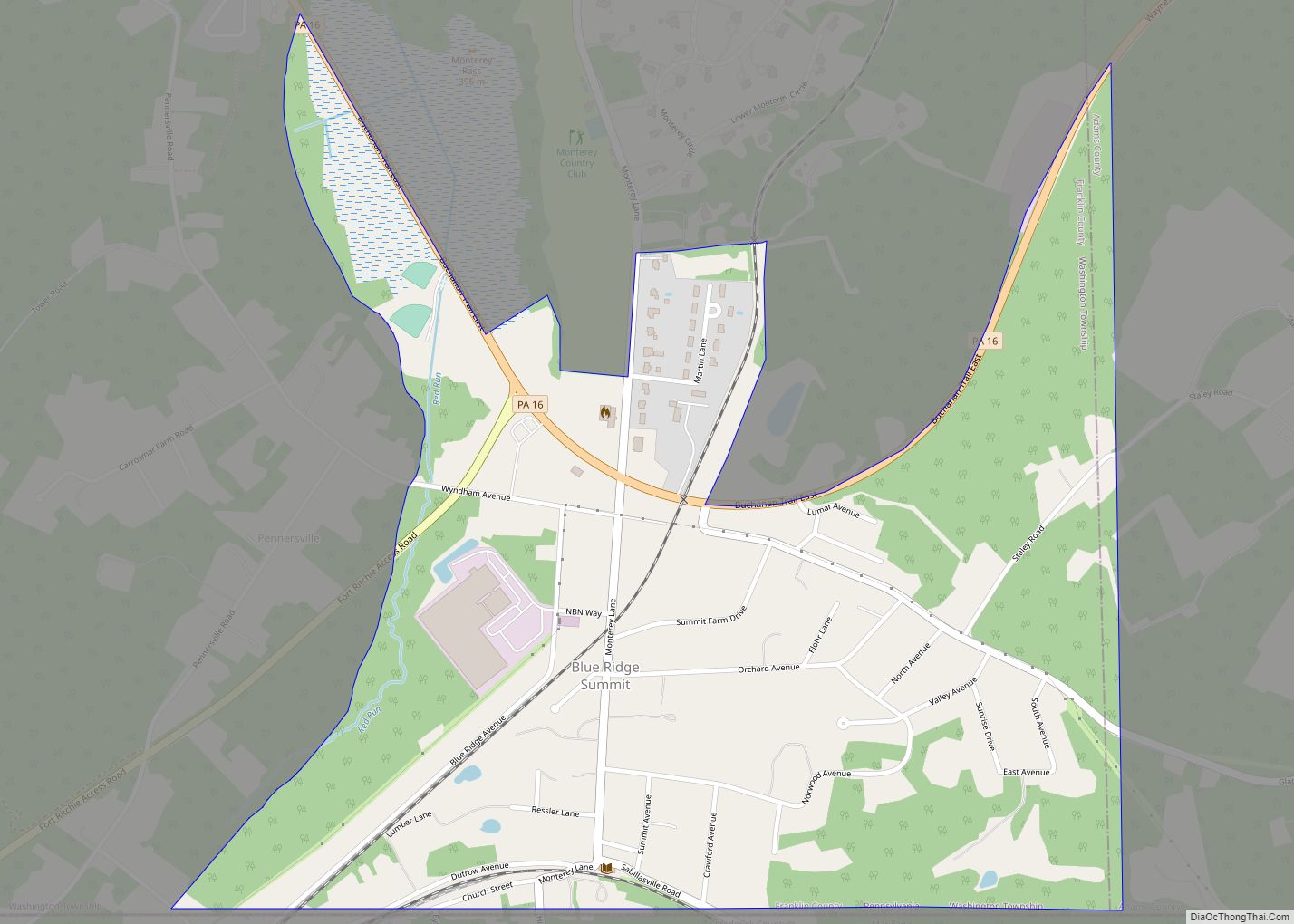

Chambersburg Road Map

Chambersburg city Satellite Map

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, Chambersburg has a total area of 6.8 square miles (17.6 km), all land. The elevation is 617 feet (188 m) above sea level. Chambersburg is located in the Cumberland Valley next to the Appalachian Mountains. It also sits right outside of Caledonia State Park, a 1,125-acre (455 ha) park with fishing and hunting areas and hiking trails, including a section of the Appalachian Trail. Also outside of Chambersburg is Michaux State Forest, a 85,000-acre (34,000 ha) forest. Both of these places provide recreation for residents.

Conococheague Creek, a noted trout stream, runs through the center of town. It is a tributary of the Potomac River. The northernmost reach of the Potomac watershed is a few miles north of town.

Climate

Chambersburg has a cold climate, according to the United States Department of Energy. The area receives anywhere from 38 to 42 inches (970 to 1,070 mm) of precipitation per year. Chambersburg falls within the warmest part of the Humid Continental Climate with some characteristics in the summer of a Humid Subtropical Climate, but bears much more characteristics of the former. The average January low is about 23 °F (−5 °C) and the average high is 37 °F (3 °C). The average July high is 85 °F (29 °C) and the average low is about 65 °F (18 °C).

See also

Map of Pennsylvania State and its subdivision:- Adams

- Allegheny

- Armstrong

- Beaver

- Bedford

- Berks

- Blair

- Bradford

- Bucks

- Butler

- Cambria

- Cameron

- Carbon

- Centre

- Chester

- Clarion

- Clearfield

- Clinton

- Columbia

- Crawford

- Cumberland

- Dauphin

- Delaware

- Elk

- Erie

- Fayette

- Forest

- Franklin

- Fulton

- Greene

- Huntingdon

- Indiana

- Jefferson

- Juniata

- Lackawanna

- Lancaster

- Lawrence

- Lebanon

- Lehigh

- Luzerne

- Lycoming

- Mc Kean

- Mercer

- Mifflin

- Monroe

- Montgomery

- Montour

- Northampton

- Northumberland

- Perry

- Philadelphia

- Pike

- Potter

- Schuylkill

- Snyder

- Somerset

- Sullivan

- Susquehanna

- Tioga

- Union

- Venango

- Warren

- Washington

- Wayne

- Westmoreland

- Wyoming

- York

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming