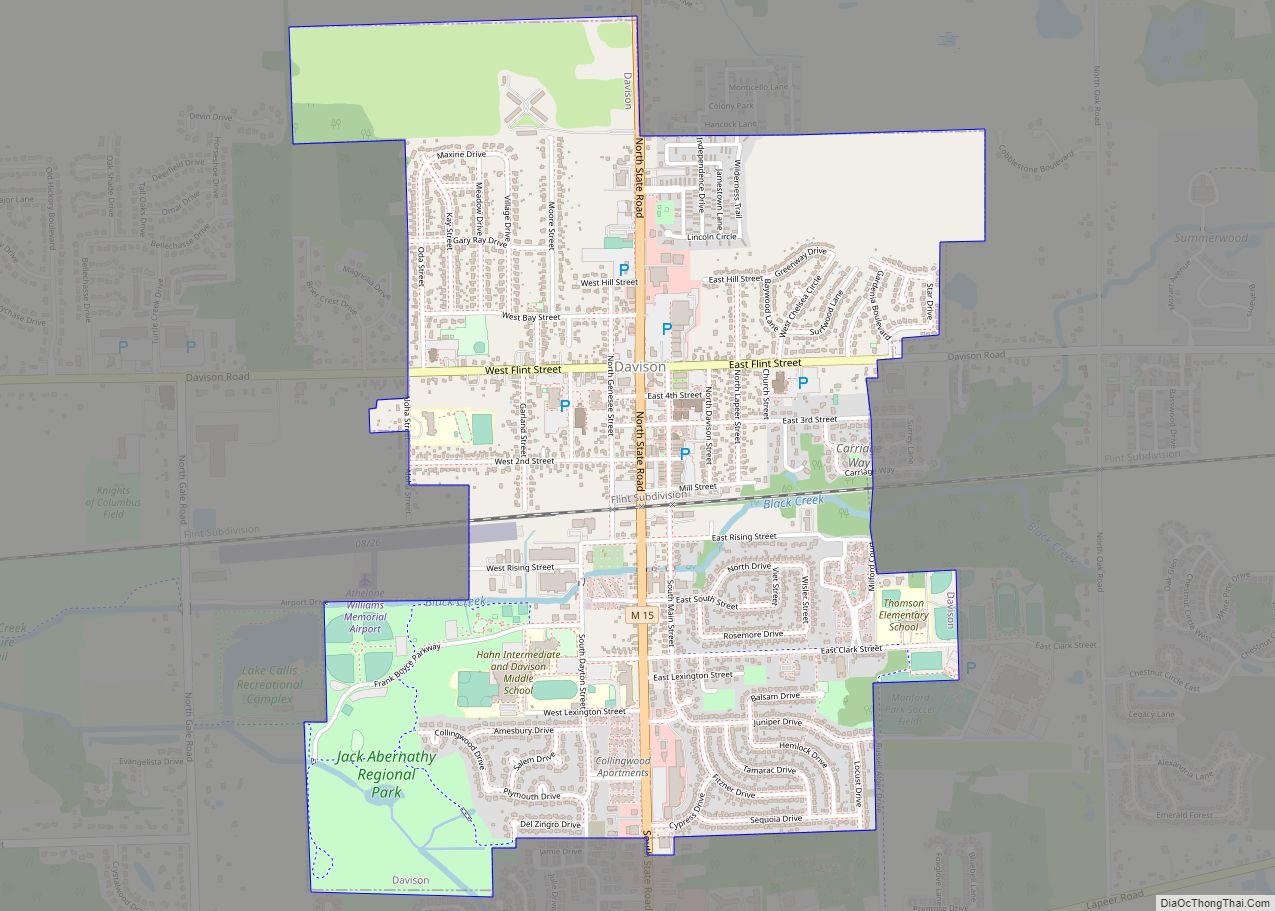

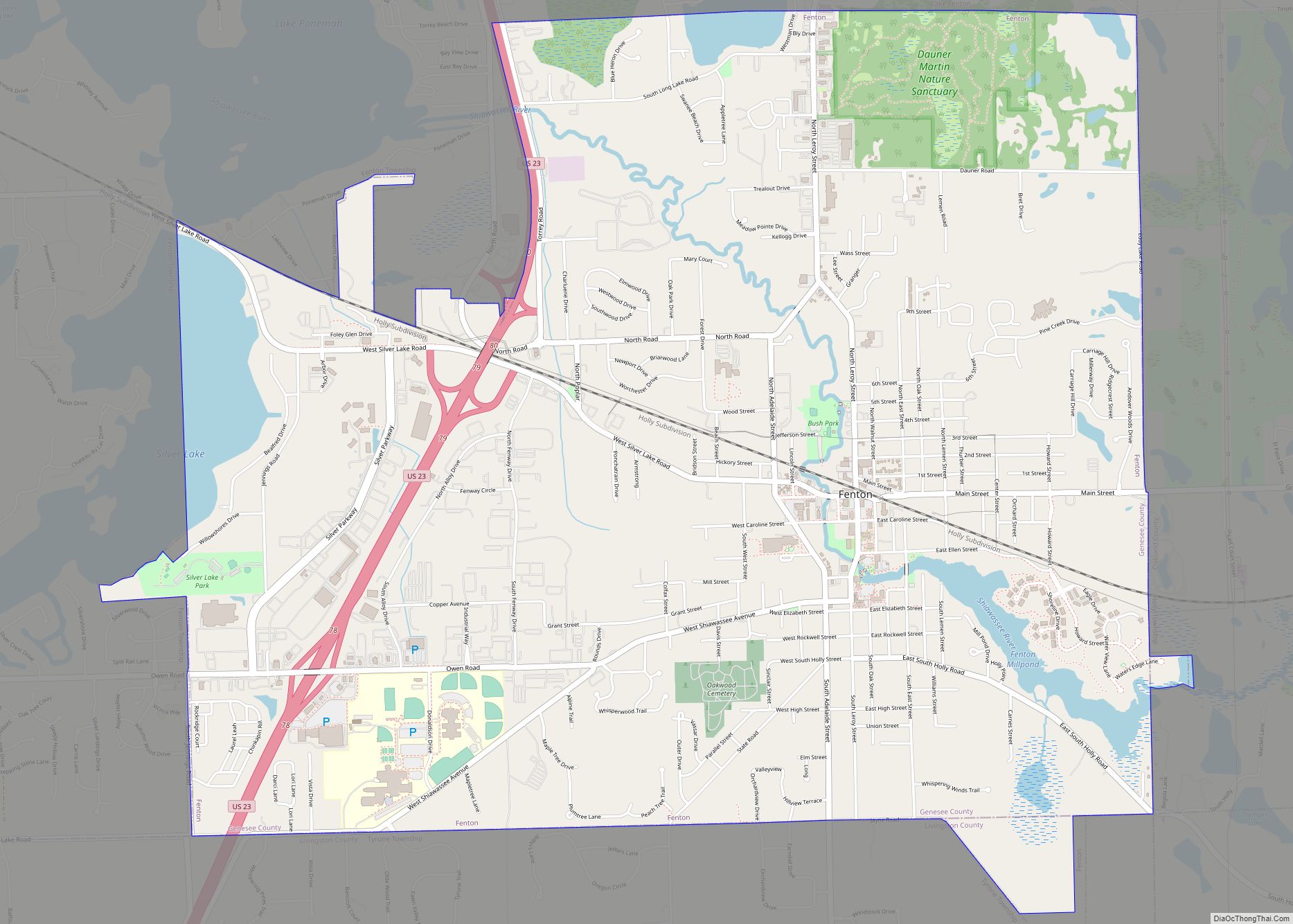

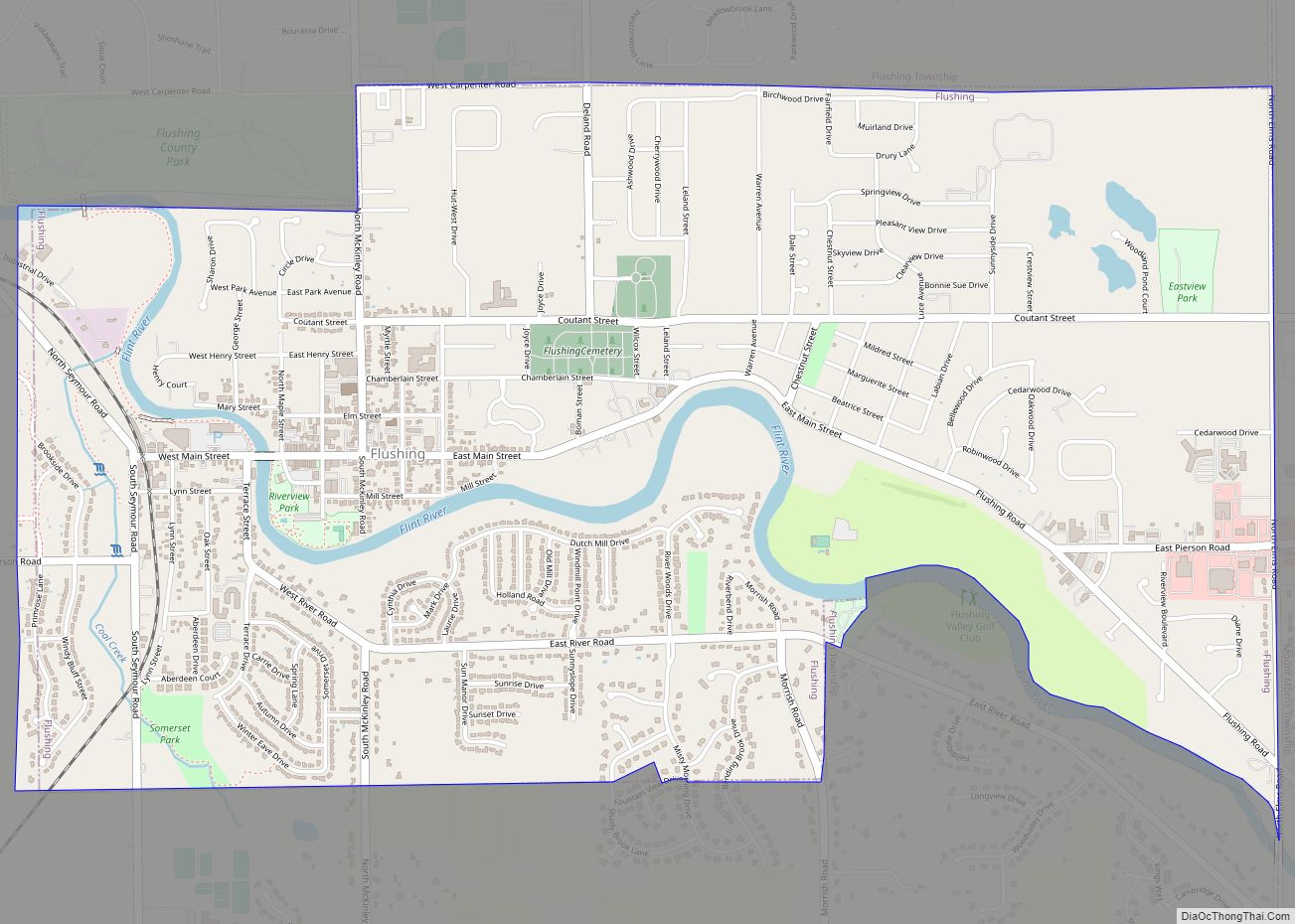

| Name: | Flint city |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 25 |

| LSAD Description: | city (suffix) |

| State: | Michigan |

| County: | Genesee County |

| Incorporated: | 1855 |

| Elevation: | 751 ft (229 m) |

| Land Area: | 33.44 sq mi (86.61 km²) |

| Water Area: | 0.67 sq mi (1.72 km²) |

| Population Density: | 2,429.78/sq mi (938.13/km²) |

| Area code: | 810 |

| FIPS code: | 2629000 |

| GNISfeature ID: | 0626170 |

| Website: | cityofflint.com |

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

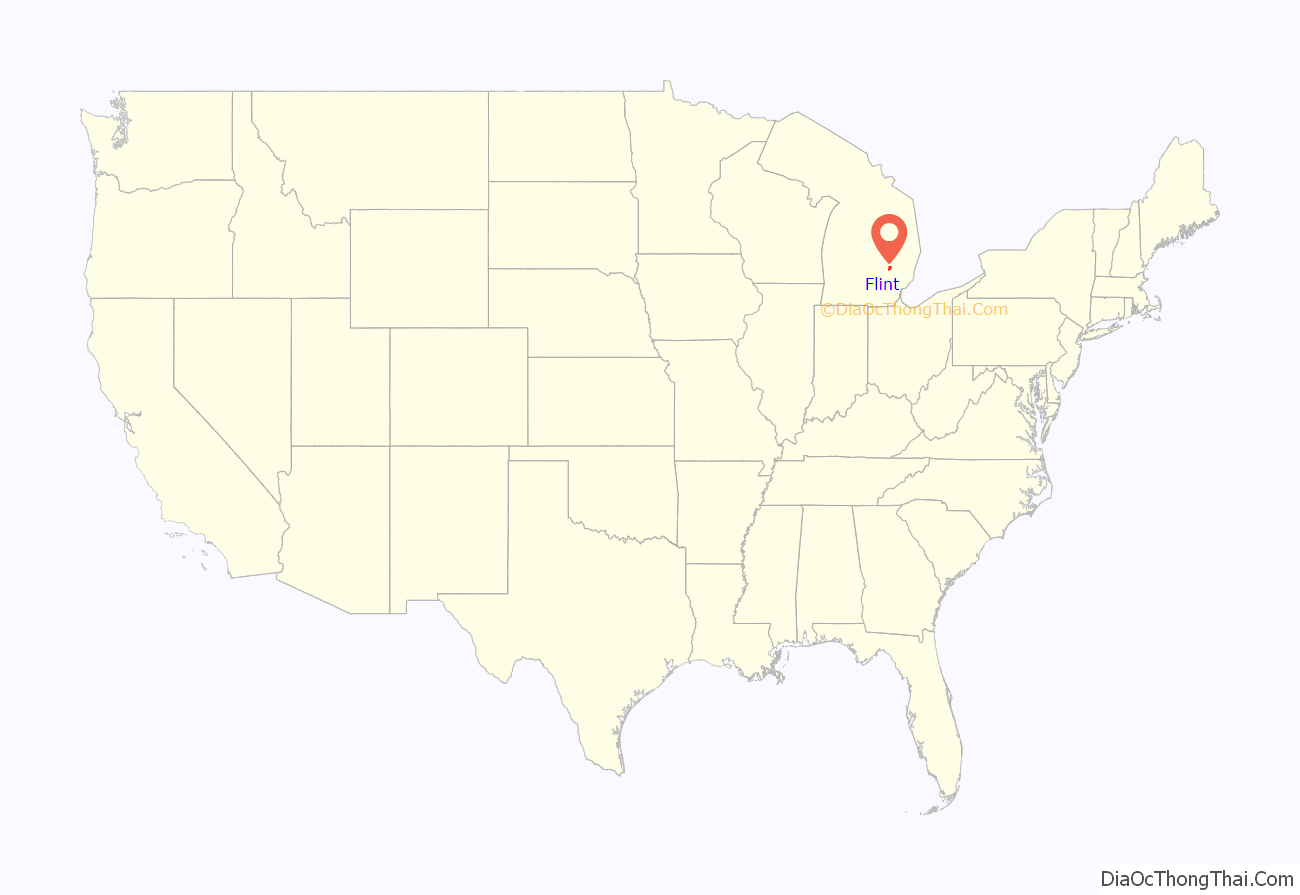

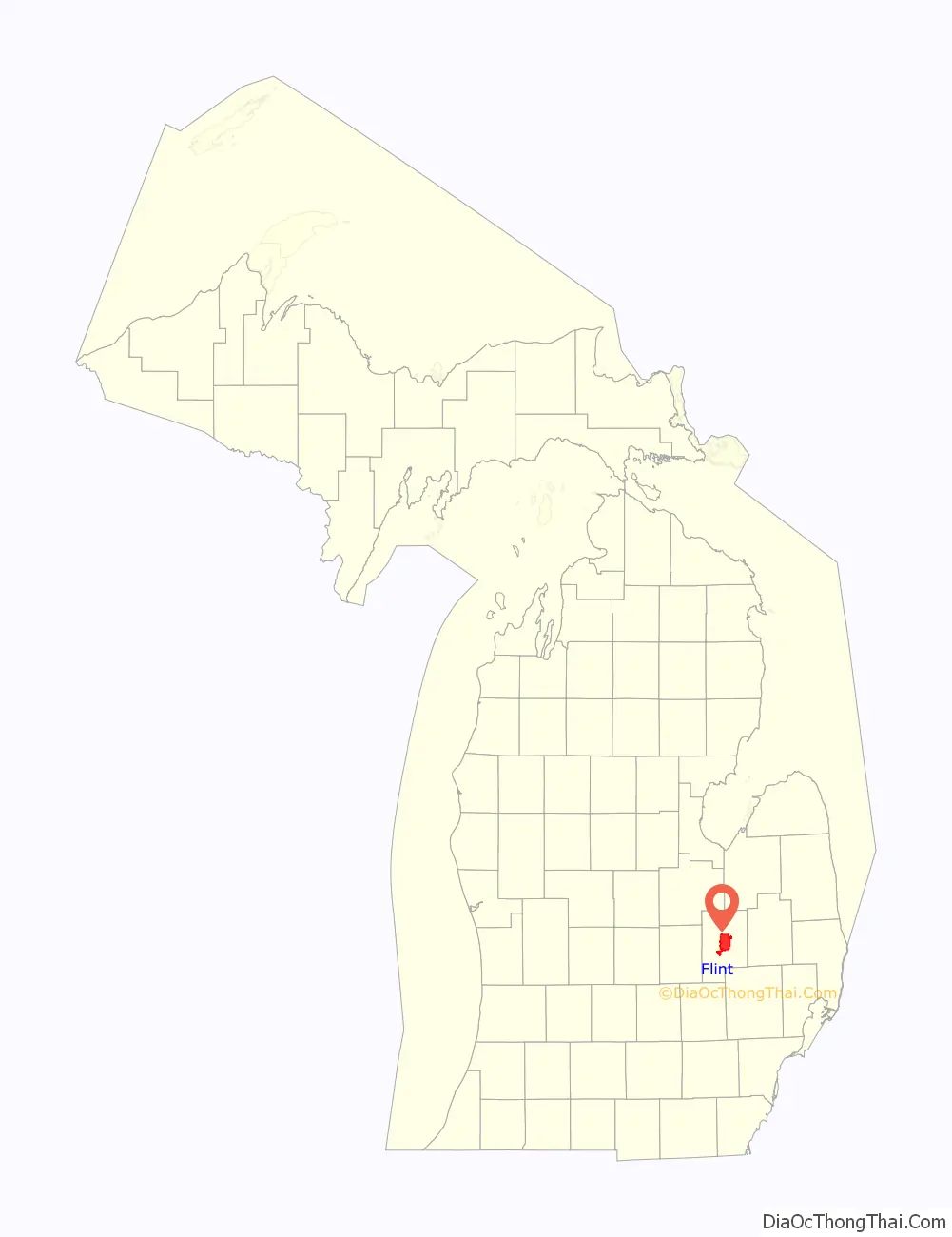

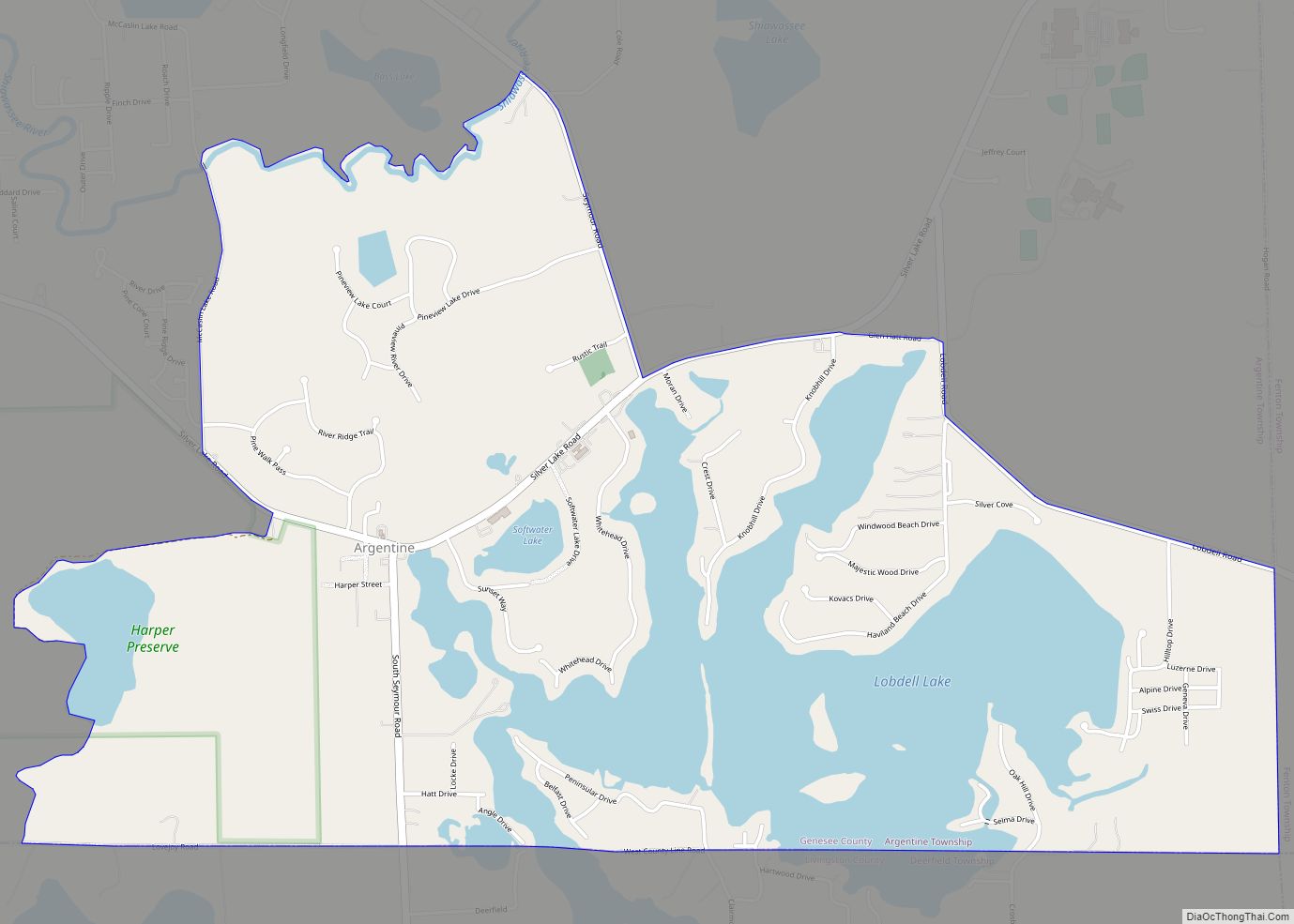

Flint location map. Where is Flint city?

History

The region was home to several Ojibwe tribes at the start of the 19th century, with a particularly significant community established near present-day Montrose. The Flint River had several convenient fords which became points of contention among rival tribes, as attested by the presence of nearby arrowheads and burial mounds. Some of the city currently resides atop ancient Ojibwe burial grounds.

19th century: lumber and the beginnings of the automobile industry

In 1819, Jacob Smith, a fur trader on cordial terms with both the local Ojibwe and the territorial government, founded a trading post at the Grand Traverse of the Flint River. On several occasions, Smith negotiated land exchanges with the Ojibwe on behalf of the U.S. government, and he was highly regarded on both sides. Smith apportioned many of his holdings to his children. As the ideal stopover on the overland route between Detroit and Saginaw, Flint grew into a small but prosperous village and incorporated in 1855. The 1860 U.S. census indicated that Genesee County had a population of 22,498 of Michigan’s 750,000.

In the latter half of the 19th century, Flint became a center of the Michigan lumber industry. Revenue from lumber funded the establishment of a local carriage-making industry. As horse-drawn carriages gave way to the automobiles, Flint then naturally grew into a major player in the nascent auto industry. Buick Motor Company, after a rudimentary start in Detroit, soon moved to Flint. AC Spark Plug originated in Flint. These were followed by several now-defunct automobile marques such as the Dort, Little, Flint, and Mason brands. Chevrolet’s first (and for many years, main) manufacturing facility was also in Flint, although the Chevrolet headquarters were in Detroit. For a brief period, all Chevrolets and Buicks were built in Flint.

The first Ladies’ Library Association in Michigan was started in Flint in 1851 in the home of Maria Smith Stockton, daughter of the founder of the community. This library, initially private, is considered the precursor of the current Flint Public Library.

Early and mid-20th century: the auto industry takes shape

In 1904, local entrepreneur William C. Durant was brought in to manage Buick, which became the largest manufacturer of automobiles by 1908. In 1908, Durant founded General Motors (GM), filing incorporation papers in New Jersey, with headquarters in Flint. GM moved its headquarters to Detroit in the mid-1920s. Durant lost control of GM twice during his lifetime. On the first occasion, he befriended Louis Chevrolet and founded Chevrolet, which was a runaway success. He used the capital from this success to buy back share control. He later lost decisive control again, permanently. Durant experienced financial ruin in the stock market crash of 1929 and subsequently ran a bowling alley in Flint until the time of his death in 1947.

The city’s mayors were targeted for recall twice, Mayor David Cuthbertson in 1924 and Mayor William H. McKeighan in 1927. Recall supporters in both cases were jailed by the police. Cuthbertson had angered the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) by the appointment of a Catholic police chief. The KKK led the recall effort and supported Judson Transue, Cutbertson’s elected successor. Transue however did not remove the police chief. McKeighan survived his recall only to face conspiracy charges in 1928. McKeighan was under investigation for a multitude of crimes which angered city leaders enough to push for changes in the city charter.

In 1928, the city adopted a new city charter with a council-manager form of government. Subsequently, McKeighan ran the “Green Slate” of candidates who won in 1931 and 1932 and he was select as mayor in 1931. In 1935, the city residents approved a charter amendment establishing the Civil Service Commission.

For the last century, Flint’s history has been dominated by both the auto industry and car culture. During the Sit-Down Strike of 1936–1937, the fledgling United Automobile Workers triumphed over General Motors, inaugurating the era of labor unions. The successful mediation of the strike by Governor Frank Murphy, culminating in a one-page agreement recognizing the Union, began an era of successful organizing by the UAW. The city was a major contributor of tanks and other war machines during World War II due to its extensive manufacturing facilities. For decades, Flint remained politically significant as a major population center as well as for its importance to the automotive industry.

A freighter named after the city, the SS City of Flint, was the first US ship to be captured during the Second World War, in October 1939. The vessel was later sunk in 1943. On June 8, 1953, the Flint-Beecher tornado, a large F5 tornado, struck the city, killing 116 people.

The city’s population peaked in 1960 at almost 200,000, at which time it was the second largest city in the state. The decades of the 1950s and 1960s are seen as the height of Flint’s prosperity and influence. They culminated with the establishment of many local institutions, most notably the Flint Cultural Center. This landmark remains one of the city’s chief commercial and artistic draws to this day. The city’s Bishop International Airport was the busiest in Michigan for United Airlines apart from Detroit Metropolitan Airport, with flights to many destinations in the Mid-West and the Mid-Atlantic.

Late 20th century: deindustrialization and demographic changes

Since the late 1960s through the end of the 20th century, Flint has suffered from disinvestment, deindustrialization, depopulation and urban decay, as well as high rates of crime, unemployment and poverty. Initially, this took the form of “white flight” that afflicted many urban industrialized American towns and cities. Given Flint’s role in the automotive industry, this decline was exacerbated by the 1973 oil crisis with spiking oil prices and the U.S. auto industry’s subsequent loss of market share to imports, as Japanese manufacturers were producing cars with better fuel economy.

In the 1980s, the rate of deindustrialization accelerated again with local GM employment falling from a 1978 high of 80,000 to under 8,000 by 2010. Only 10% of the manufacturing work force from its height remains in Flint. Many factors have been blamed, including outsourcing, offshoring, increased automation, and moving jobs to non-union facilities in right to work states and foreign countries.

This decline was highlighted in the film Roger & Me by Michael Moore (the title refers to Roger B. Smith, the CEO of General Motors during the 1980s). Also highlighted in Moore’s documentary was the failure of city officials to reverse the trends with entertainment options (e.g. the now-demolished AutoWorld) during the 1980s. Moore, a native of Davison (a Flint suburb), revisited Flint in his later movies, including Bowling for Columbine, Fahrenheit 9/11, and Fahrenheit 11/9.

21st century

By 2002, Flint had accrued $30 million in debt. On March 5, 2002, the city’s voters recalled Mayor Woodrow Stanley. On May 22, Governor John Engler declared a financial emergency in Flint, and on July 8 the state appointed an emergency financial manager, Ed Kurtz. The emergency financial manager displaced the temporary mayor, Darnell Earley, in the city administrator position.

In August 2002, city voters elected former Mayor James Rutherford to finish the remainder of Stanley’s term of office. On September 24, Kurtz commissioned a salary and wage study for top city officials from an outside accounting and consulting firm. The financial manager then installed a new code enforcement program for annual rental inspections and emergency demolitions. On October 8, Kurtz ordered cuts in pay for the mayor (from $107,000 to $24,000) and the City Council members (from $23,000 to $18,000). He also eliminated insurance benefits for most officials. After spending $245,000 fighting the takeover, the City Council ended the lawsuits on October 14. Immediately thereafter on October 16, a new interim financial plan was put in place by the manager. This plan initiated controls on hiring, overnight travel and spending by city employees. On November 12, Kurtz directed the city’s retirement board to stop unusual pension benefits, which had decreased some retiree pensions by 3.5%. Kurtz sought the return of overpayments to the pension fund. However, in December, the state attorney general stated that emergency financial managers do not have authority over the retirement system. With contract talks stalled, Kurtz stated that there either need to be cuts or layoffs to union employees. That same month, the city’s recreation centers were temporarily closed.

Emergency measures continued in 2003. In May, Kurtz increased water and sewer bills by 11% and shut down operations of the ombudsman’s office. In September, a 4% pay cut was agreed to by the city’s largest union. In October, Kurtz moved in favor of infrastructure improvements, authorizing $1 million in sewer and road projects. Don Williamson was elected a full-term mayor and sworn in on November 10. In December, city audits reported nearly $14 million in reductions in the city deficit. For the 2003–2004 budget year, estimates decreased that amount to between $6 million and $8 million.

With pressure from Kurtz for large layoffs and replacement of the board on February 17, 2004, the City Retirement Board agreed to four proposals reducing the amount of the city’s contribution into the system. On March 24, Kurtz indicated that he would raise the City Council’s and the mayor’s pay, and in May, Kurtz laid off 10 workers as part of 35 job cuts for the 2004–05 budget. In June 2004, Kurtz reported that the financial emergency was over.

In November 2013, American Cast Iron Pipe Company, a Birmingham, Alabama based company, became the first to build a production facility in Flint’s former Buick City site, purchasing the property from the RACER Trust. Commercially, local organizations have attempted to pool their resources in the central business district and to expand and bolster higher education at four local institutions. Examples of their efforts include the following:

- Landmarks such as the First National Bank building have been extensively renovated, often to create lofts or office space, and filming for the Will Ferrell movie Semi-Pro resulted in renovations to the Capitol Theatre.

- The Paterson Building at Saginaw and Third street has been owned by the Collison Family, Thomas W. Collison & Co., Inc., for the last 30 years. The building is rich in Art Deco throughout the interior and exterior. The building also houses its own garage in the lower level, providing heated valet parking to The Paterson Building Tenants.

- In 2004, University Park, the first planned residential community in Flint in over 30 years, was built north of Fifth Avenue off Saginaw Street, Flint’s main thoroughfare.

- Local foundations have funded the renovation and redecoration of Saginaw Street and have begun work turning University Avenue (formerly known as Third Avenue) into a mile-long “University Corridor” connecting University of Michigan–Flint with Kettering University.

- Atwood Stadium, located on University Avenue, received extensive renovations, and the Cultivating Our Community project landscaped 16 different locations as a part of a $415,600 beautification project.

- Wade Trim and Rowe Incorporated made major renovations to transform empty downtown Flint blocks into business, entertainment, and housing centers. WNEM-TV, a television station based in Saginaw, uses space in the Wade Trim building facing Saginaw Street as a secondary studio and newsroom.

- The long-vacant Durant Hotel, formerly owned by the United Hotels Company, was turned into a mixture of commercial space and apartments intended to attract young professionals or college students, with 93 units.

- In March 2008, the Crim Race Foundation put up an offer to buy the vacant Character Inn and turn it into a fitness center and do a multimillion-dollar renovation.

Similar to a plan in Detroit, Flint is in the process of tearing down thousands of abandoned homes to create available real estate. As of June 2009, approximately 1,100 homes have been demolished in Flint, with one official estimating another 3,000 more will have to be torn down.

On September 30, 2011, Governor Rick Snyder appointed an eight-member team to review Flint’s financial state with a request to report back in 30 days (half the legal time for a review). On November 8, Mayor Dayne Walling defeated challenger Darryl Buchanan 8,819 votes (56%) to 6,868 votes (44%). That same day, the Michigan State review panel declared Flint to be in a state of a “local government financial emergency” recommending the state again appoint an emergency manager. On November 14, the City Council voted 7 to 2 to not appeal the state review with Mayor Walling concurring the next day. Governor Snyder appointed Michael Brown as the city’s emergency manager. On December 2, Brown dismissed a number of top administrators. Pay and benefits from Flint’s elected officials were automatically removed. On December 8, the office of ombudsman and the Civil Service Commission were eliminated by Brown.

On January 16, 2012, protestors against the emergency manager law including Flint residents marched near the governor’s home. The next day, Brown filed a financial and operating plan with the state as mandated by law. The next month, each ward in the city had a community engagement meeting hosted by Brown. Governor Snyder on March 7 made a statewide public safety message from Flint City Hall that included help for Flint with plans for reopening the Flint lockup and increasing state police patrols in Flint.

On March 20, 2012, days after a lawsuit was filed by labor union AFSCME, and a restraining order was issued against Brown, his appointment was found to be in violation of the Michigan Open Meetings Act, and Mayor Walling and the City Council had their powers returned. The state immediately filed an emergency appeal, claiming the financial emergency still existed. On March 26, the appeal was granted, putting Brown back in power. Brown and several unions agreed to new contract terms in April. Brown unveiled his fiscal year 2013 budget on April 23. It included cuts in nearly every department including police and fire, as well as higher taxes. An Obsolete Property Rehabilitation District was created by Manager Brown in June 2012 for 11 downtown Flint properties. On July 19, the city pension system was transferred to the Municipal Employees Retirement System by the city’s retirement board which led to a legal challenge.

On August 3, 2012, the Michigan Supreme Court ordered the state Board of Canvassers to certify a referendum on Public Act 4, the Emergency Manager Law, for the November ballot. Brown made several actions on August 7 including placing a $6 million public safety millage on the ballot and sold Genesee Towers to a development group for $1 to demolish the structure. The board certified the referendum petition on August 8, returning the previous Emergency Financial Manager Law into effect. With Brown previously temporary mayor for the last few years, he was ineligible to be the Emergency Financial Manager. Ed Kurtz was once again appointed Emergency Financial Manager by the Emergency Financial Assistance Loan Board.

Two lawsuits were filed in September 2012, one by the city council against Kurtz’s appointment, while another was against the state in Ingham County Circuit Court claiming the old emergency financial manager law remains repealed. On November 30, State Treasurer Andy Dillon announced the financial emergency was still ongoing, and the emergency manager was still needed.

Michael Brown was re-appointed Emergency Manager on June 26, 2013, and returned to work on July 8. Flint had an $11.3 million projected deficit when Brown started as emergency manager in 2011. The city faced a $19.1 million combined deficit from 2012, with plans to borrow $12 million to cover part of it. Brown resigned from his position in early September 2013, and his last day was October 31. He was succeeded by Saginaw city manager (and former Flint temporary mayor) Darnell Earley.

Earley formed a blue ribbon committee on governance with 23 members on January 16, 2014, to review city operations and consider possible charter amendments. The blue ribbon committee recommend that the city move to a council-manager government. Six charter amendment proposals were placed on the November 4, 2014, ballot with the charter review commission proposal passing along with reduction of mayoral staff appointments and budgetary amendments. Proposals which would eliminate certain executive departments, the Civil Service Commission and the ombudsman office were defeated. Flint elected a nine-member Charter Review Commission on May 5, 2015.

With Earley appointed to be emergency manager for Detroit Public Schools on January 13, 2015, city financial adviser Jerry Ambrose was selected to finish out the financial emergency with an expected exit in April. On April 30, 2015, the state moved the city from under an emergency manager receivership to a Receivership Transition Advisory Board. On November 3, 2015, Flint residents elected Karen Weaver as their first female mayor. On January 22, 2016, the Receivership Transition Advisory Board unanimously voted to return some powers, including appointment authority, to the mayor. The Receivership Transit Authority Board was formally dissolved by State Treasurer Nick Khouri on April 10, 2018, returning the city to local control.

In April 2014, during a financial crisis, state-appointed emergency manager Darnell Earley changed Flint’s water source from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department (sourced from Lake Huron) to the Flint River. The problem was compounded with the fact that anticorrosive measures were not implemented. After two independent studies, lead poisoning caused by the water was found in the area’s population. This has led to several lawsuits, the resignation of several officials, fifteen criminal indictments, and a federal public health state of emergency for all of Genesee County.

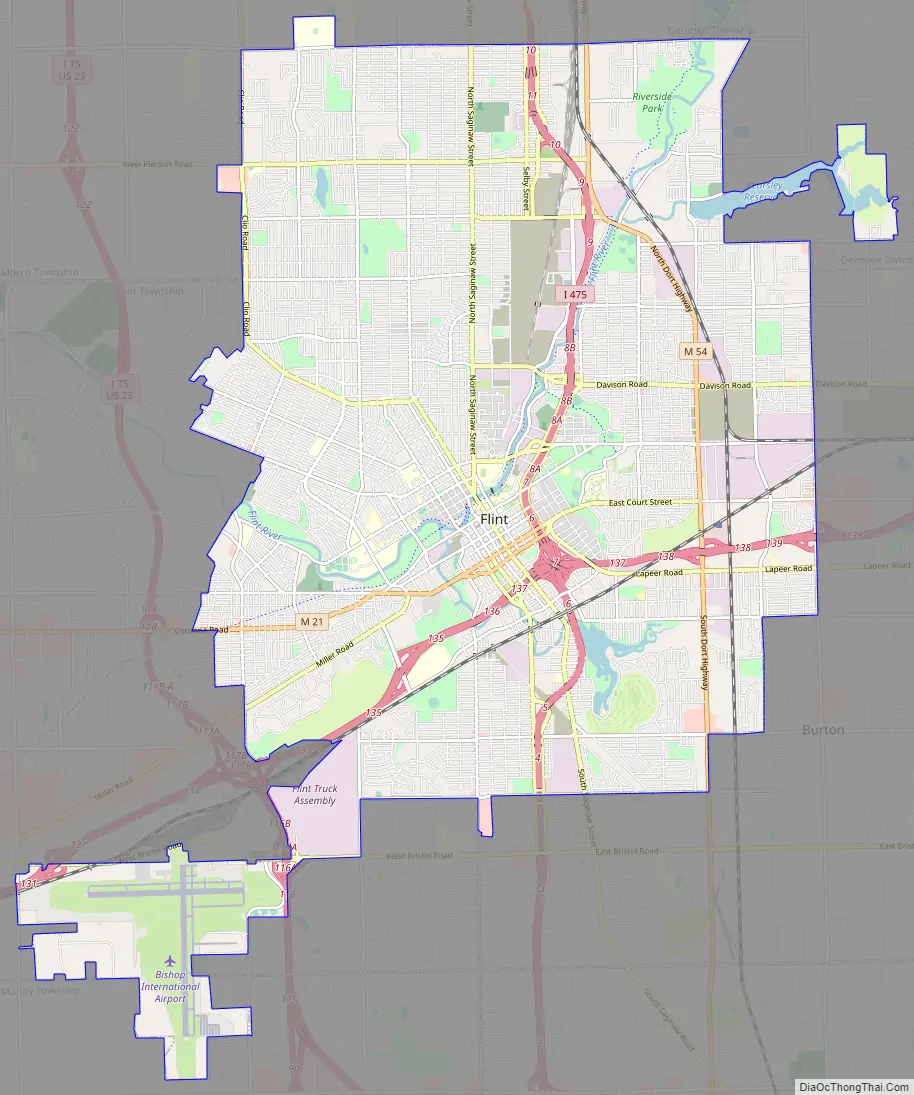

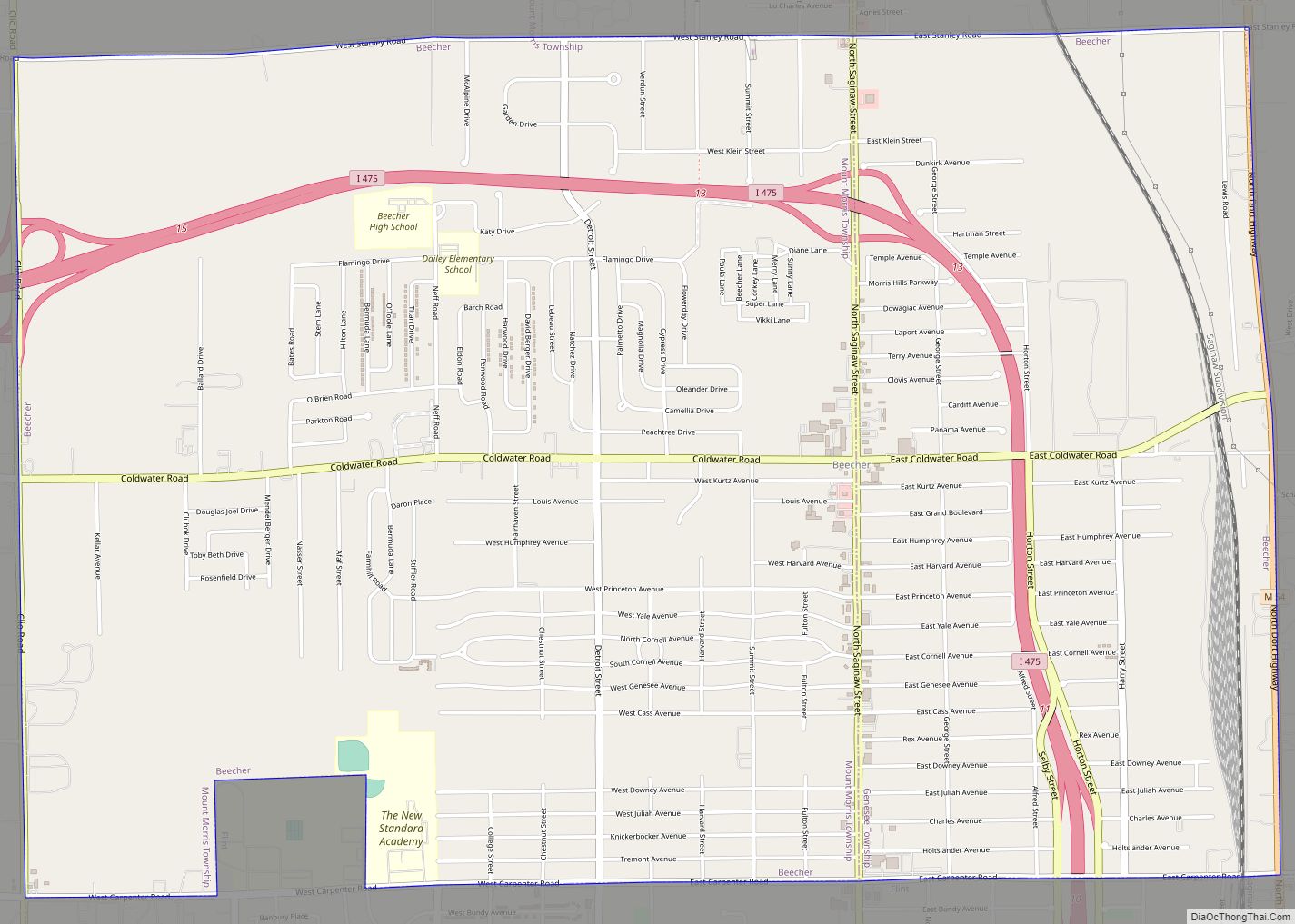

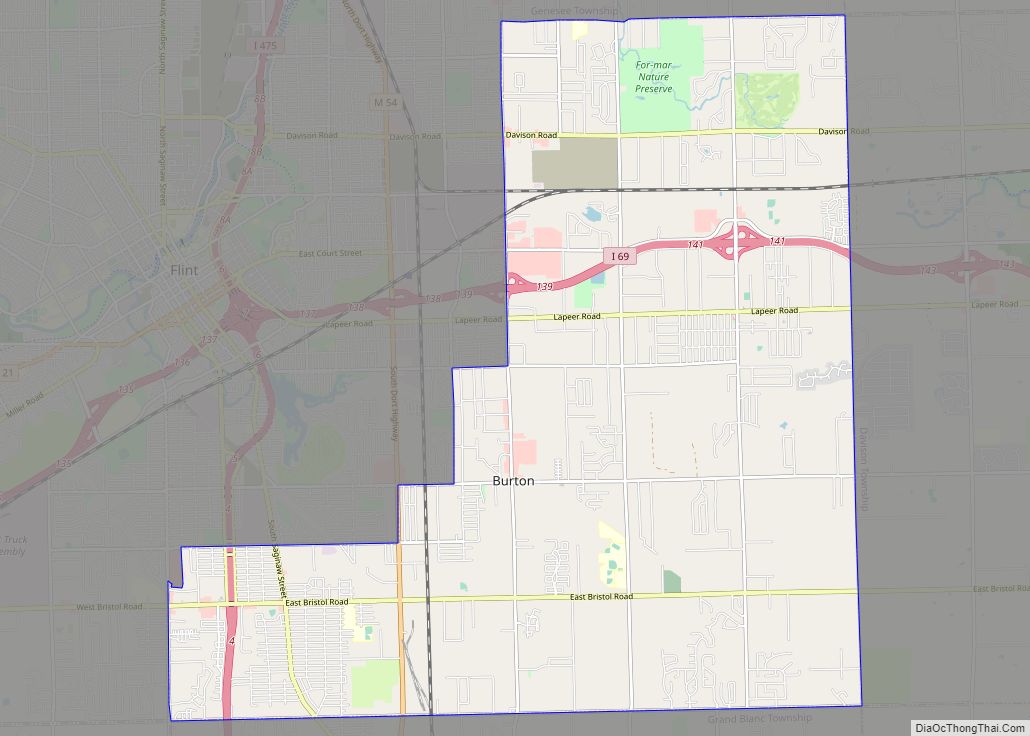

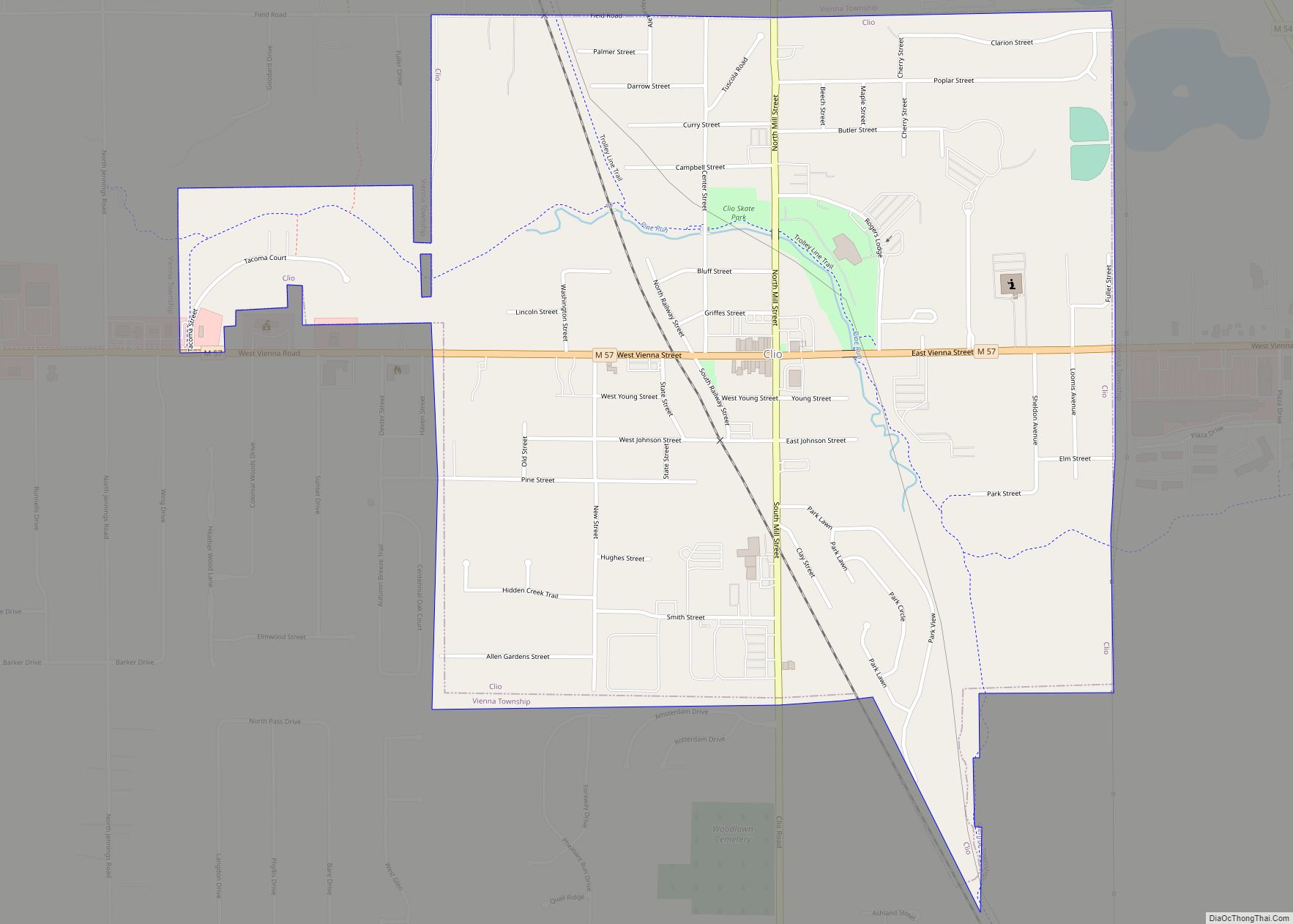

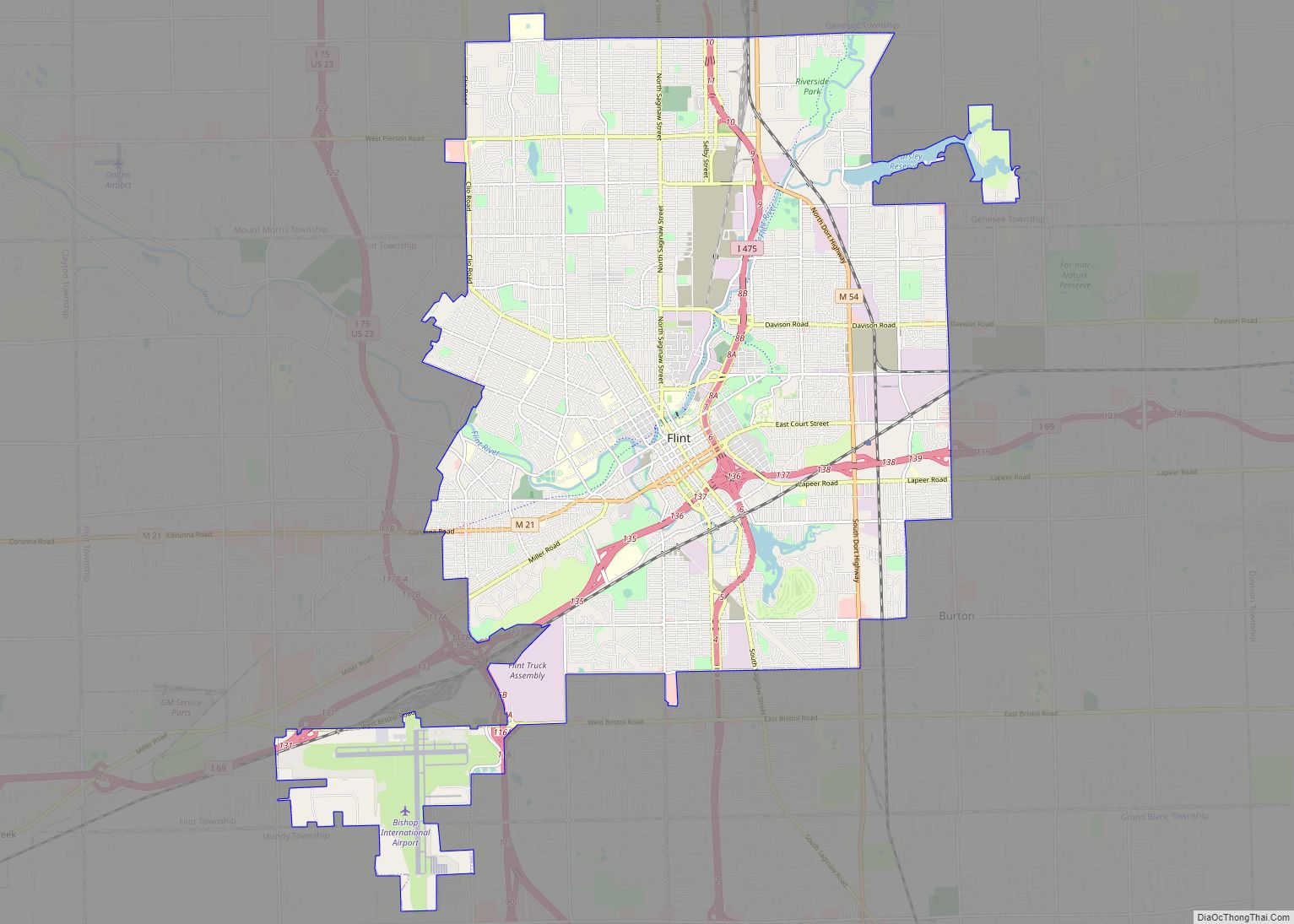

Flint Road Map

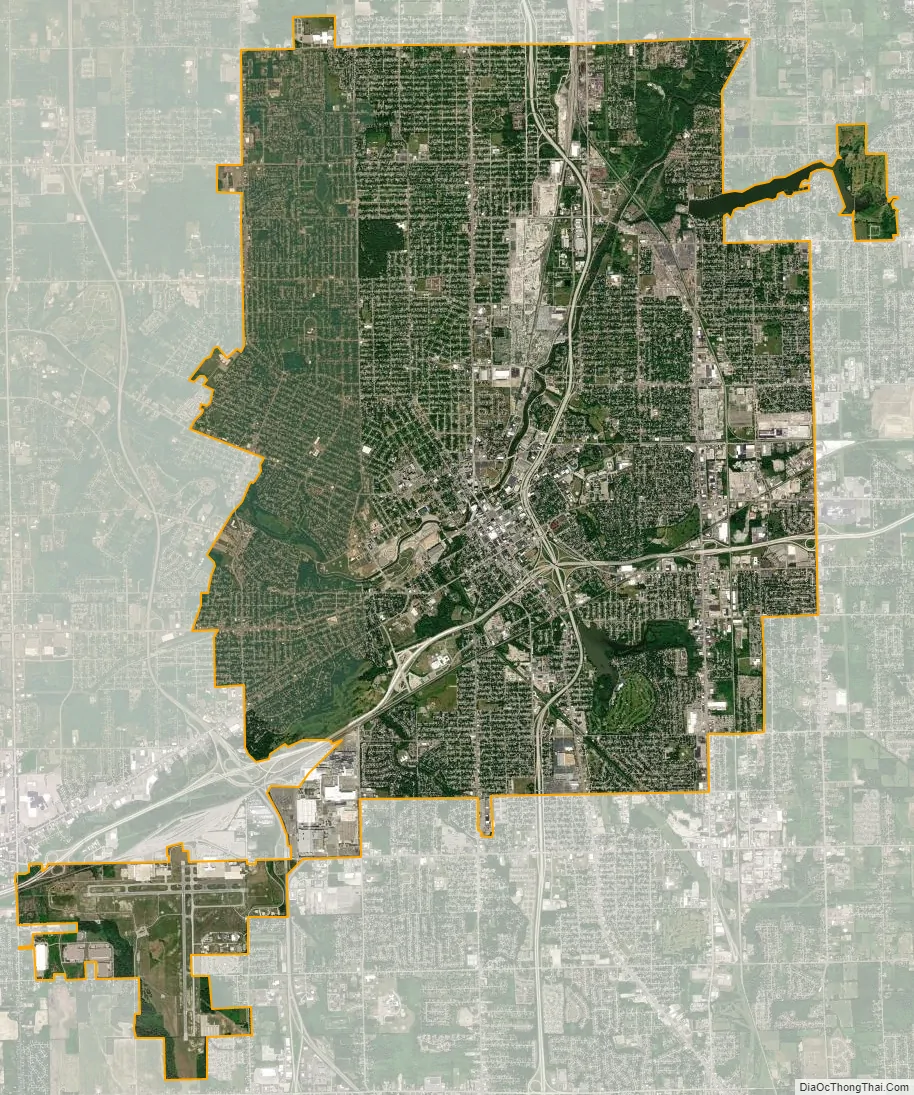

Flint city Satellite Map

Geography

Flint lies in the Flint/Tri-Cities region of Michigan. Flint and Genesee County can be categorized as a subregion of Flint/Tri-Cities. It is located along the Flint River, which flows through Lapeer, Genesee, and Saginaw counties and is 78.3 mi (126.0 km) long.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 34.06 square miles (88.21 km), of which, 33.42 square miles (86.56 km) is land and 0.64 square miles (1.66 km) is water. Flint lies just to the northeast of the Flint hills. The terrain is low and rolling along the south and east sides, and flatter to the northwest.

Neighborhoods

Flint has several neighborhoods grouped around the center of the city on the four cardinal sides. The downtown business district is centered on Saginaw Street south of the Flint River. Just west, on opposite sides of the river, are Carriage Town (north) and the Grand Traverse Street District (south). Both neighborhoods boast strong neighborhood associations. These neighborhoods were the center of manufacturing for and profits from the nation’s carriage industry until the 1920s and are the site of many well-preserved Victorian homes and the setting of Atwood Stadium.

The University Avenue corridor of Carriage Town is home to the largest concentration of Greek housing in the area, with fraternity houses from both Kettering University, and the University of Michigan-Flint. Chapter houses include Phi Delta Theta, Sigma Alpha Epsilon, Delta Chi, Theta Chi, Lambda Chi Alpha, Theta Xi, Alpha Phi Alpha, Phi Gamma Delta, and Delta Tau Delta Fraternities.

Just north of downtown is River Village, an example of gentrification via mixed-income public housing. To the east of I-475 is Central Park and Fairfield Village. These are the only two neighborhoods between UM-Flint and Mott Community College and enjoy strong neighborhood associations. Central Park piloted a project to convert street lights to LED and is defined by seven cul-de-sacs.

The North Side and 5th Ward are predominantly African American, with such historic districts as Buick City and Civic Park on the north, and Sugar Hill, Floral Park, and Kent and Elm Parks on the south. Many of these neighborhoods were the original centers of early Michigan blues. The South Side in particular was also a center for multi-racial migration from Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, and the Deep South since World War II. These neighborhoods are most often lower income but have maintained some level of economic stratification. The East Side is the site of the Applewood Mott Estate, and Mott Community College, the Cultural Center, and East Village, one of Flint’s more prosperous areas. The surrounding neighborhood is called the College/Cultural Neighborhood, with a strong neighborhood association, lower crime rate and stable housing prices.

Just north is Eastside Proper, also known as the State Streets, and has much of Flint’s Hispanic community. The West Side includes the main site of the 1936–37 sit-down strike, the Mott Park neighborhood, Kettering University, and the historic Woodcroft Estates, owned in the past by legendary automotive executives and current home to prominent and historic Flint families such as the Motts, the Manleys, and the Smiths.

Facilities associated with General Motors in the past and present are scattered throughout the city, including GM Truck and Bus, Flint Metal Center and Powertrain South (clustered together on the city’s southwestern corner); Powertrain North, Flint Tool and Die and Delphi East. The largest plant, Buick City, and adjacent facilities have been demolished.

Half of Flint’s fourteen tallest buildings were built during the 1920s. The 19-story Genesee Towers, formerly the city’s tallest building, was completed in 1968. The building became unused in later years and fell into severe disrepair: a cautionary sign warning of falling debris was put on the sidewalk in front of it. An investment company purchased the building for $1, and it was demolished (by implosion) on December 22, 2013.

Climate

Typical of southeastern Michigan, Flint has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb), and is part of USDA Hardiness zone 6a. Winters are cold, with moderate snowfall and temperatures not rising above freezing on an average 52 days annually, while dropping to 0 °F (−18 °C) or below on an average 9.3 days a year; summers are warm to hot with temperatures exceeding 90 °F (32 °C) on 9.0 days. The monthly daily mean temperature ranges from 23.0 °F (−5.0 °C) in January to 70.9 °F (21.6 °C) in July. Official temperature extremes range from 108 °F (42 °C) on July 8 and 13, 1936 down to −25 °F (−32 °C) on January 18, 1976, and February 20, 2015; the record low maximum is −4 °F (−20 °C) on January 18, 1994, while, conversely the record high minimum is 79 °F (26 °C) on July 18, 1942. Decades may pass between readings of 100 °F (38 °C) or higher, which last occurred July 17, 2012. The average window for freezing temperatures is October 8 thru May 7, allowing a growing season of 153 days. On June 8, 1953, Flint was hit by an F5 tornado, which claimed 116 lives.

Precipitation is moderate and somewhat evenly-distributed throughout the year, although the warmer months average more, averaging 31.97 inches (812 mm) annually, but historically ranging from 18.08 in (459 mm) in 1963 to 45.38 in (1,153 mm) in 1975. Snowfall, which typically falls in measurable amounts between November 12 through April 9 (occasionally in October and very rarely in May), averages 52.1 inches (132 cm) per year, although historically ranging from 16.0 in (41 cm) in 1944–45 to 85.3 in (217 cm) in 2017–18. A snow depth of 1 in (2.5 cm) or more occurs on an average 64 days, with 53 days from December to February.

See also

Map of Michigan State and its subdivision:- Alcona

- Alger

- Allegan

- Alpena

- Antrim

- Arenac

- Baraga

- Barry

- Bay

- Benzie

- Berrien

- Branch

- Calhoun

- Cass

- Charlevoix

- Cheboygan

- Chippewa

- Clare

- Clinton

- Crawford

- Delta

- Dickinson

- Eaton

- Emmet

- Genesee

- Gladwin

- Gogebic

- Grand Traverse

- Gratiot

- Hillsdale

- Houghton

- Huron

- Ingham

- Ionia

- Iosco

- Iron

- Isabella

- Jackson

- Kalamazoo

- Kalkaska

- Kent

- Keweenaw

- Lake

- Lake Hurron

- Lake Michigan

- Lake St. Clair

- Lake Superior

- Lapeer

- Leelanau

- Lenawee

- Livingston

- Luce

- Mackinac

- Macomb

- Manistee

- Marquette

- Mason

- Mecosta

- Menominee

- Midland

- Missaukee

- Monroe

- Montcalm

- Montmorency

- Muskegon

- Newaygo

- Oakland

- Oceana

- Ogemaw

- Ontonagon

- Osceola

- Oscoda

- Otsego

- Ottawa

- Presque Isle

- Roscommon

- Saginaw

- Saint Clair

- Saint Joseph

- Sanilac

- Schoolcraft

- Shiawassee

- Tuscola

- Van Buren

- Washtenaw

- Wayne

- Wexford

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming