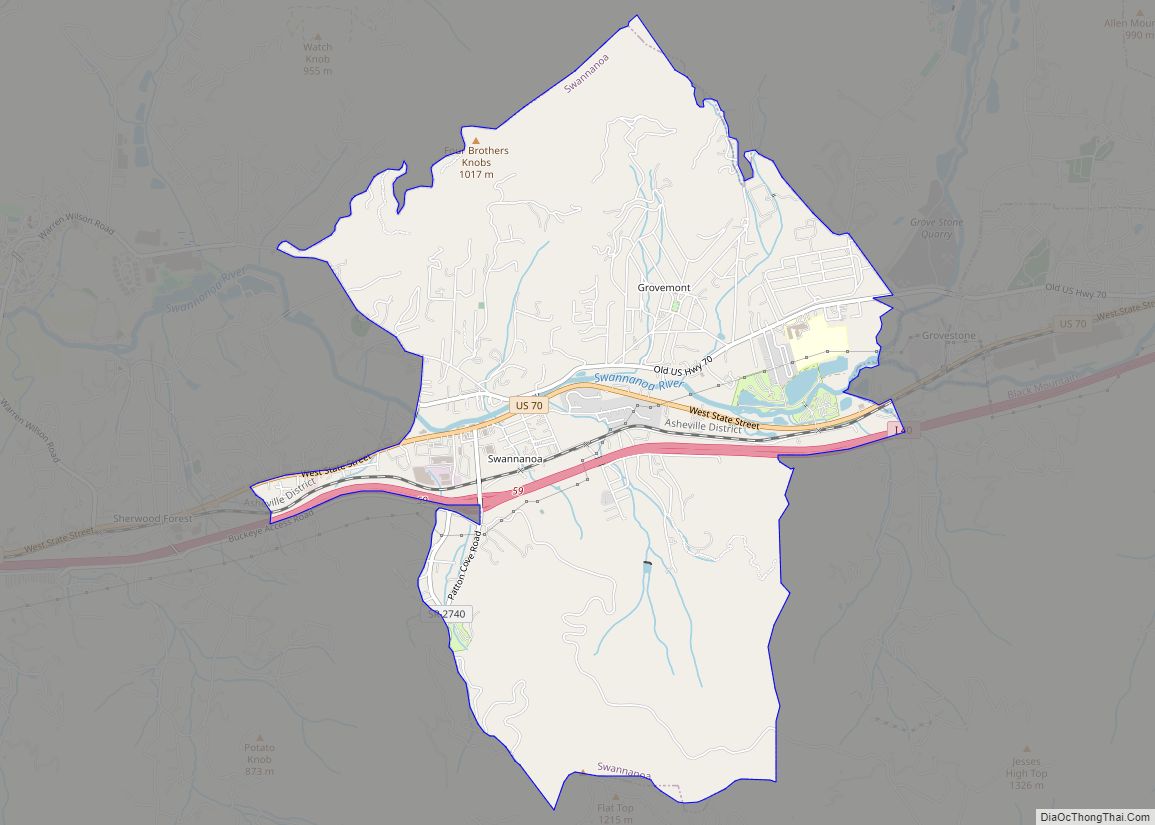

Asheville (/ˈæʃvɪl/ ASH-vil) is a city in, and the county seat of, Buncombe County, North Carolina. Located at the confluence of the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers, it is the largest city in Western North Carolina, and the state’s 11th-most populous city. According to the 2020 census, the city’s population was 94,589, up from 83,393 in the 2010 census. It is the principal city in the four-county Asheville metropolitan area, which had a population of 424,858 in 2010, and of 469,015 in 2020.

| Name: | Asheville city |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 25 |

| LSAD Description: | city (suffix) |

| State: | North Carolina |

| County: | Buncombe County |

| Incorporated: | 1797 |

| Elevation: | 2,134 ft (650 m) |

| Land Area: | 45.47 sq mi (117.77 km²) |

| Water Area: | 0.39 sq mi (1.00 km²) 0.66% |

| Population Density: | 2,080.20/sq mi (803.18/km²) |

| Area code: | 828 |

| FIPS code: | 3702140 |

| GNISfeature ID: | 1018864 |

| Website: | www.ashevillenc.gov |

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

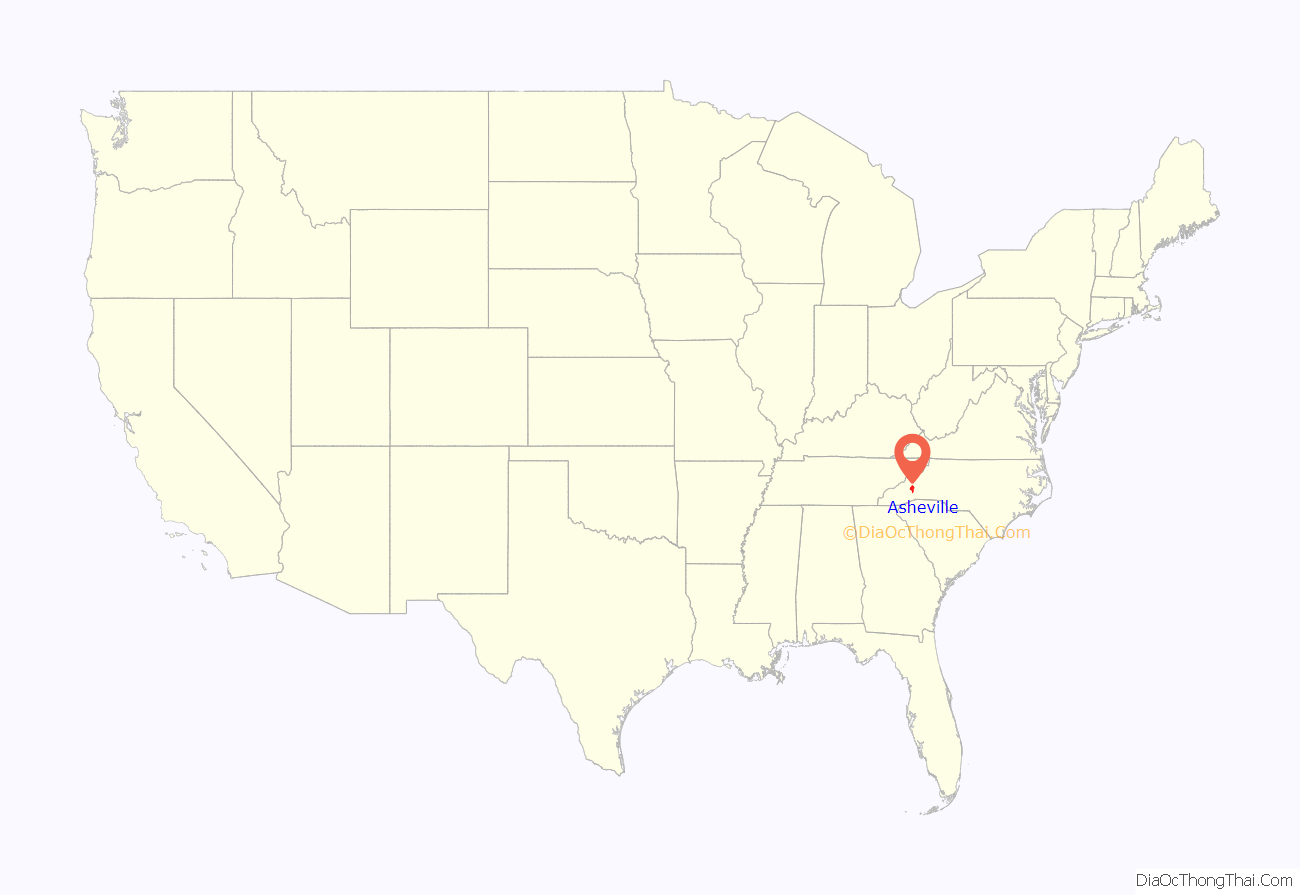

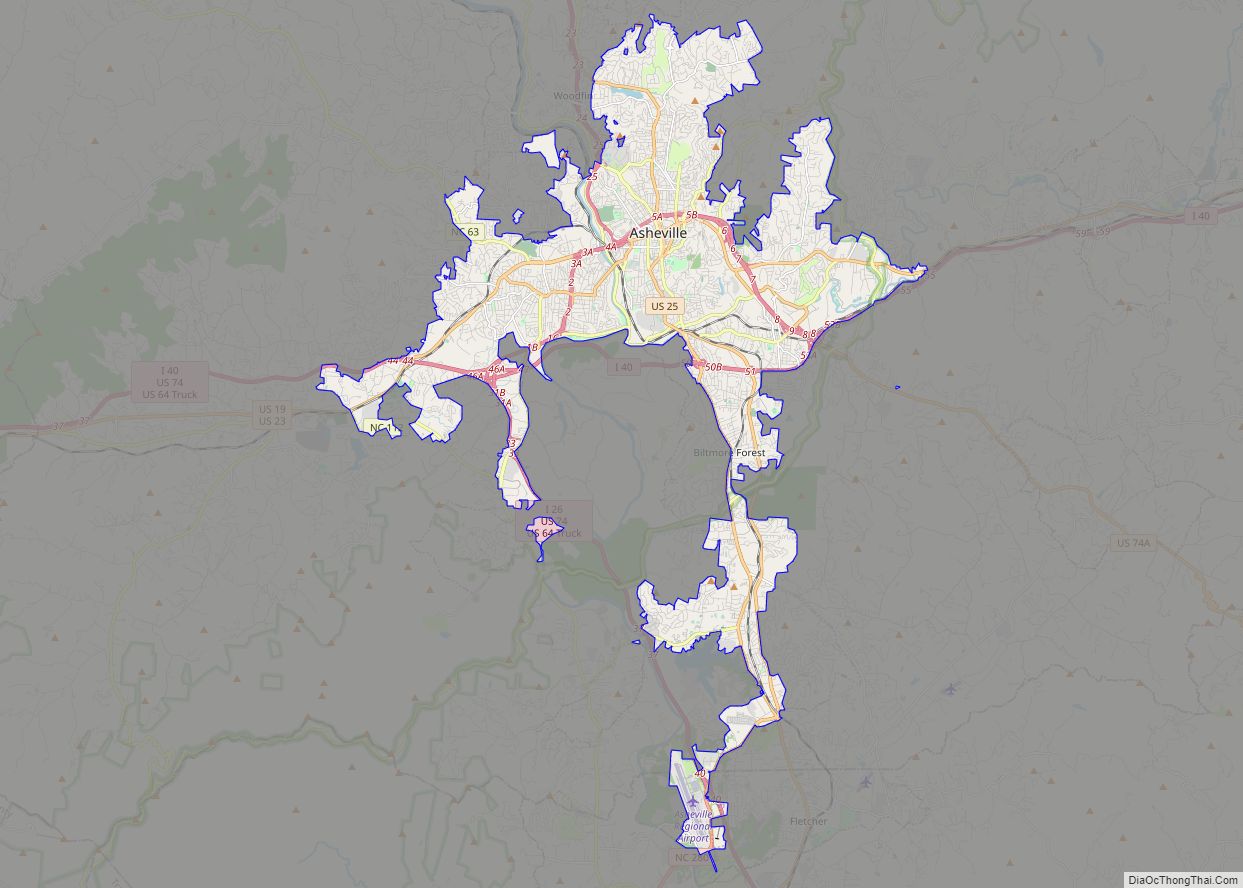

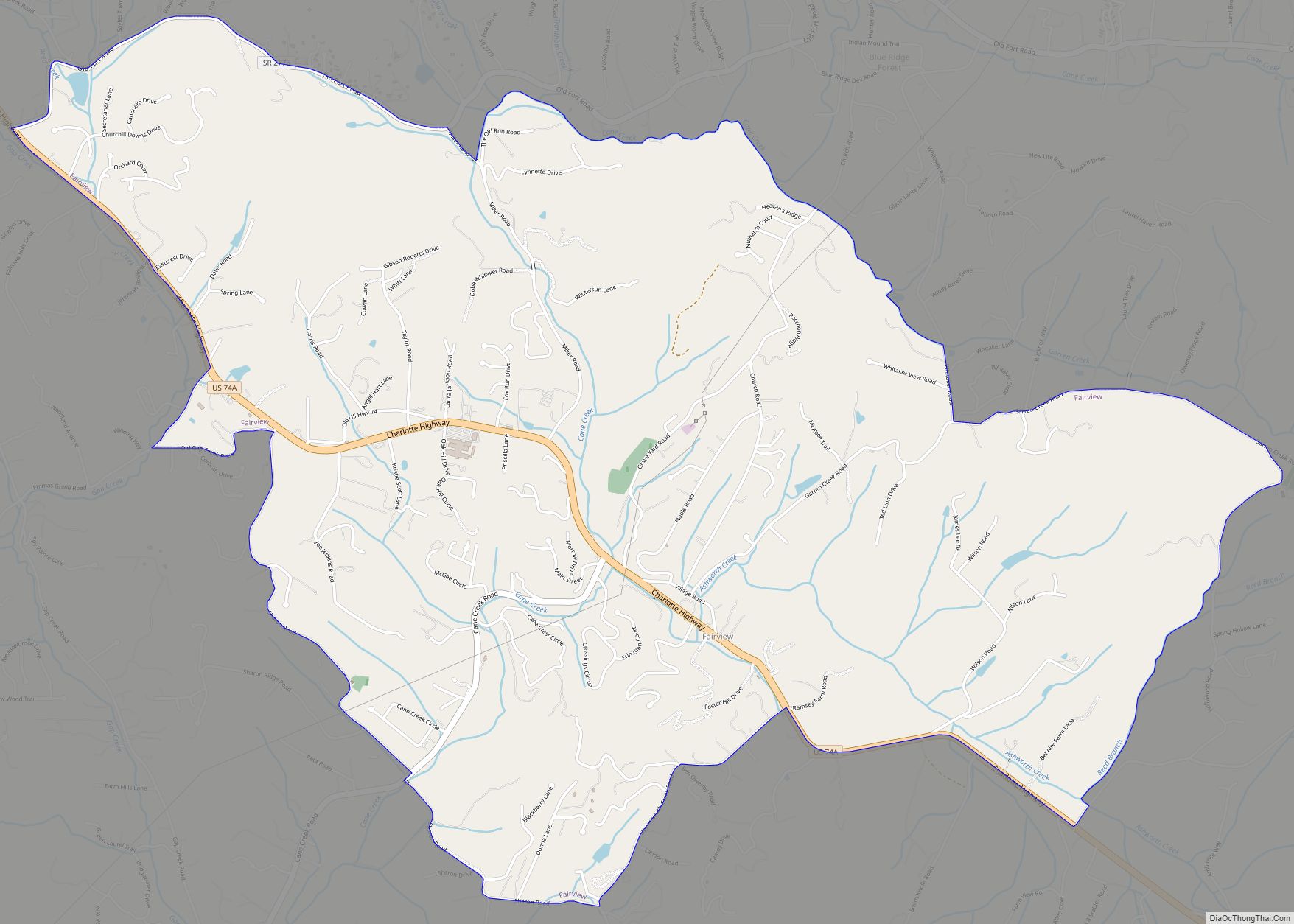

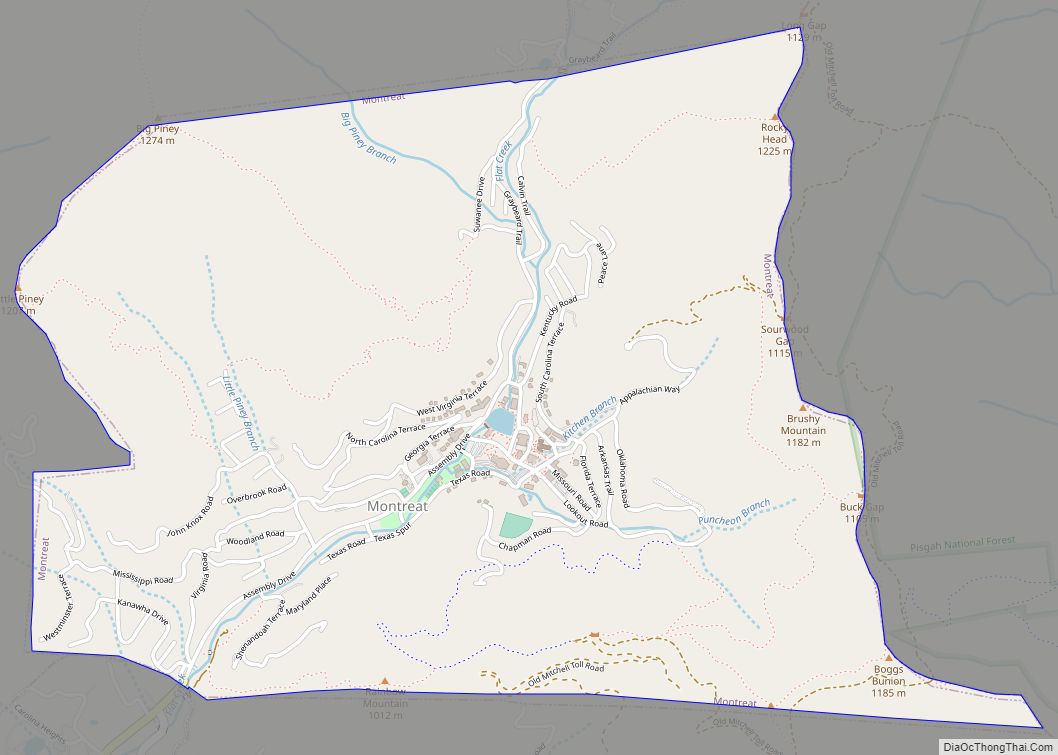

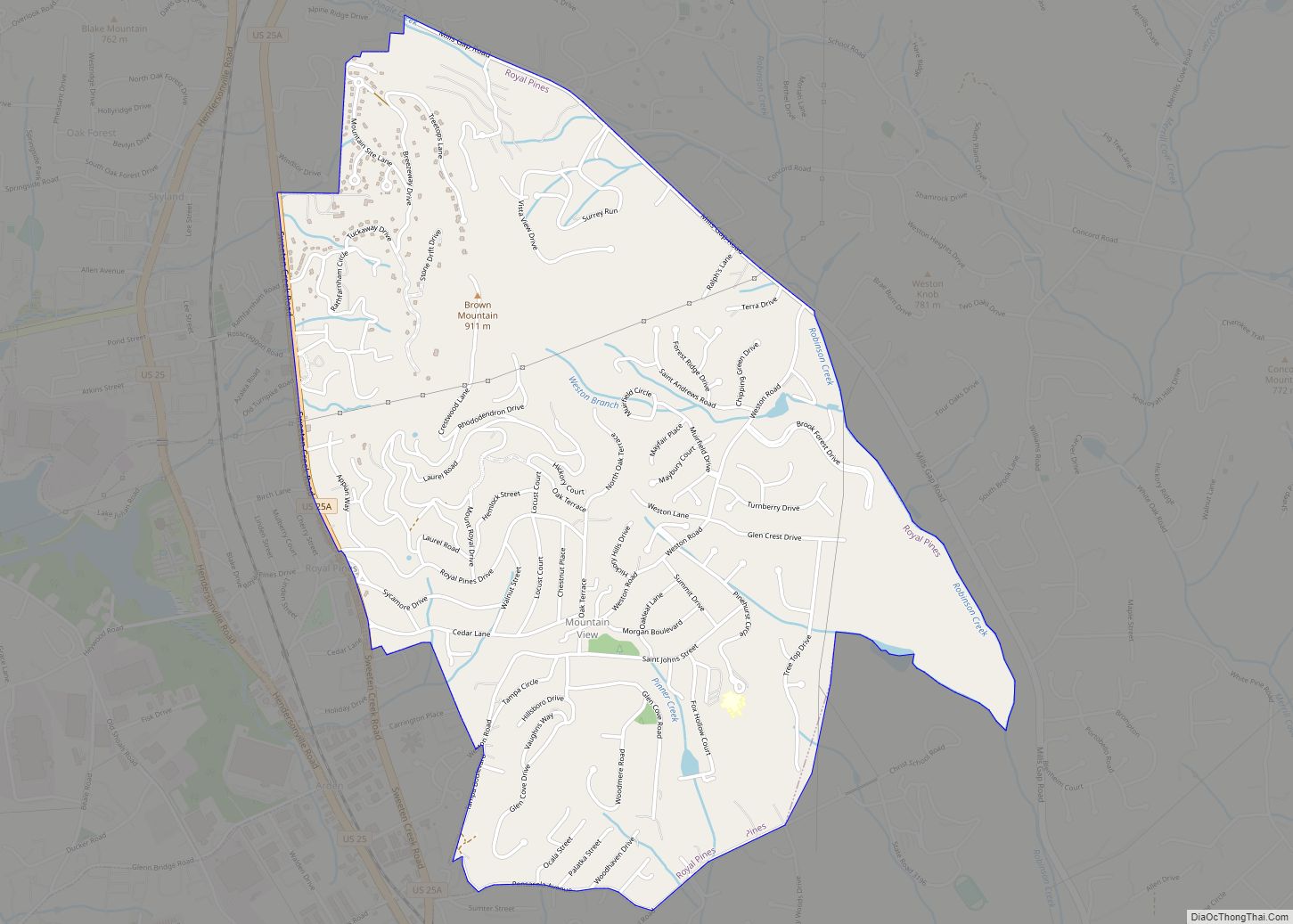

Asheville location map. Where is Asheville city?

History

Origins

Before the arrival of the Europeans, the land where Asheville now exists lay within the boundaries of the Cherokee Nation, which had homelands in modern western North and South Carolina, southeastern Tennessee, and northeastern Georgia. A town at the site of the river confluence was recorded as Guaxule by Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto during his 1540 expedition through this area. His expedition comprised the first European visitors, who carried endemic Eurasian infectious diseases that killed many in the native population.

The Cherokee had traditionally used the area by the confluence for open hunting and meeting grounds. They called it Untokiasdiyi (in Cherokee), meaning “Where they race”, until the middle of the 19th century.

European Americans began to settle in the area of Asheville in 1784, after the United States gained independence in the American Revolutionary War. In that year, Colonel Samuel Davidson and his family settled in the Swannanoa Valley, redeeming a soldier’s land grant from the state of North Carolina made in lieu of pay. Soon after building a log cabin at the bank of Christian Creek, Davidson was lured into the woods and killed by a band of Cherokee hunters resisting white encroachment. Davidson’s wife, child, and female slave fled on foot overnight to Davidson’s Fort (named after Davidson’s father General John Davidson) 16 miles away.

In response to the killing, Davidson’s twin brother Major William Davidson and brother-in-law Colonel Daniel Smith formed an expedition to retrieve Samuel Davidson’s body and avenge his murder. Months after the expedition, Major Davidson and other members of his extended family returned to the area and settled at the mouth of Bee Tree Creek.

The U.S. Census of 1790 counted 1,000 residents of the area, excluding the Cherokee Native Americans as a separate nation. Buncombe County was officially formed in 1792. In the 1800 US Census, some 107 settlers in the county were slaveholders, owning a total of 300 enslaved African Americans. Total county population was 5,812.

The county seat, named “Morristown” in 1793, was established on a plateau where two old Indian trails crossed. In 1797, Morristown was incorporated and renamed “Asheville” after North Carolina Governor Samuel Ashe.

In the 1800s, James McDowell established land for burial of slaves belonging to his and the Smith families in Asheville. His son William Wallace McDowell continued this practice, setting aside about two acres of land for this purpose.

Civil War

On the eve of the Civil War, James W. Patton, son of an Irish immigrant, was the largest slaveholder in the county, and had built a luxurious mansion, known as The Henrietta, in Asheville. Buncombe County had the largest number of prominent slaveholders in Western North Carolina, many in the professional class based in Asheville, numbering a total of 293 countywide in 1863.

Asheville, with a population of about 2,500 by 1861, remained relatively untouched by battles of the Civil War. The city contributed a number of companies to the Confederate States Army, as well as a number for the Union Army. For a time, an Enfield rifle manufacturing facility was located in the town.

The war did not reach Asheville until early April 1865, when the “Battle of Asheville” was fought at the present-day site of the University of North Carolina at Asheville. Union forces withdrew to Tennessee, which they had occupied since 1862. They had encountered resistance in Asheville from a small group of Confederate senior and junior reserves, and recuperating Confederate soldiers in prepared trench lines across the Buncombe Turnpike. The Union force had been ordered to take Asheville only if they could accomplish it without significant losses.

An engagement was fought later that month at Swannanoa Gap, as part of the larger Stoneman’s Raid throughout western North Carolina, Virginia and Tennessee. Union forces retreated in the face of resistance from Brig. Gen. Martin, commander of Confederate troops in western North Carolina. Later, Union forces returned to the area via Howard’s Gap and Henderson County. In late April 1865, North Carolina Union troops from the 3rd North Carolina Mounted Infantry, under the overall command of Union Gen. George Stoneman, captured Asheville. After a negotiated departure, the 2,700 troops left town, accompanied by “hundreds of freed slaves.”

The slave George Avery was among 40 slaves known to have traveled with the troops to Tennessee. There he enlisted in the US Colored Troops. He returned to Asheville after being formally discharged in 1866. After the war, he was hired by his former master William W. McDowell to manage the South Asheville Cemetery, a public place for black burials. This is the oldest and largest black public cemetery in the state. By 1943, when the last burial was conducted, it held remains of an estimated 2,000 people.

Later, the federal troops returned and plundered Asheville, burning a number of Confederate supporters’ homes in Asheville.

1880s

On October 2, 1880, the Western North Carolina Railroad completed its line from Salisbury to Asheville, the first rail line to reach the city. Almost immediately it was sold and resold to the Richmond and Danville Railroad Company, becoming part of the Southern Railway in 1894. With the completion of the first railway, Asheville developed with steady growth as industrial plants increased in number and size, and new residents built homes. Textile mills were built to process cotton from the region, and other plants were set up to manufacture wood and mica products, foodstuffs, and other commodities.

The 21-mile (34 km) distance between Hendersonville and Asheville of the former Asheville and Spartanburg Railroad was completed in 1886. By that point, the line was operated as part of the Richmond and Danville Railroad until 1894 and controlled by the Southern Railway afterward. Following major changes in the industry because of the competition from automobiles, railroad restructuring resulted in Asheville’s final passenger train, a coach-only remnant of the Southern Railway’s Carolina Special, making its last run on December 5, 1968.

Asheville had the first electric street railway lines in the state of North Carolina, the first of which opened in 1889. These were replaced by buses in 1934.

1900s

In 1900, Asheville was the third-largest city in the state, behind Wilmington and Charlotte. Asheville prospered in the decades of the 1910s and 1920s. During these years, Rutherford P. Hayes, son of President Rutherford B. Hayes, bought land, and worked with the prominent African-American businessman Edward W. Pearson, Sr. to develop his land for residential housing known as the African-American Burton Street Community. Hayes also worked to establish a sanitary district in West Asheville, which became an incorporated town in 1913, and merged with Asheville in 1917.

The Asheville Masonic Temple was constructed in 1913, under the direction of famed architect Richard Sharp Smith, a Freemason. It was the meeting place for local Masons through much of the 20th century.

On July 15–16, 1916, the Asheville area was subject to severe flooding from the remnants of a tropical storm which caused more than $3 million in damage. Areas flooded included part of the Biltmore Estate, and the company that ran it sold some of the property to lower their maintenance costs. This area was later developed as an independent jurisdiction known as Biltmore Forest, which is now one of the wealthiest in the country.

The Great Depression hit Asheville quite hard. On November 20, 1930, eight local banks failed. Only Wachovia remained open with infusions of cash from Winston-Salem. Because of the explosive growth of the previous decades, the per capita debt owed by the city (through municipal bonds) was the highest in the nation. By 1929, both the city and Buncombe County had incurred over $56 million in bonded debt to pay for a wide range of municipal and infrastructure improvements, including City Hall, the water system, Beaucatcher Tunnel, and Asheville High School. Rather than default, the city paid those debts over a period of fifty years.

From the start of the depression through the 1980s, economic growth in Asheville was slow. During this time of financial stagnation, most of the buildings in the downtown district remained unaltered. As a result, Asheville has one of the most impressive, comprehensive collections of Art Deco architecture in the United States.

In 1959, the city council would purchase property partially located in neighboring Henderson County for the development of Asheville Regional Airport. The North Carolina General Assembly would pass a bill that would to redesign the boundaries of Buncombe and Henderson to include the proposed airport property entirely in Buncombe, allowing Asheville to annex the complete site.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, urban renewal displaced much of Asheville’s African-American population. Asheville’s neighborhoods of Montford and Kenilworth, now mostly white, used to have a majority of black home owners. Since the late 20th century, there has been an effort to maintain and preserve the South Asheville Cemetery, in the Kenilworth neighborhood. It is the largest public black cemetery in the state, holding about 2000 burials, dating from the early 1800s and slavery years, to 1943. Fewer than 100 of the graves are marked by tombstones.

2000s to present

In 2003, Centennial Olympic Park bomber Eric Robert Rudolph was transported to Asheville from Murphy, North Carolina, for arraignment in federal court.

In September 2004, remnants of Hurricanes Frances and Ivan caused major flooding in Asheville, particularly at Biltmore Village. In 2006, the Asheville Zombie Walk was organized for the first time, starting a tradition that lasted until 2016.

In July 2020, the Asheville City Council voted to provide reparations to Black residents for the city’s “historic role in slavery, discrimination and denial of basic liberties”. The resolution was unanimously passed, and Asheville committed to “make investments in areas where Black residents face disparities”. Also in 2020, efforts were made to remove or change several monuments in the city that celebrated the Confederate States of America or slave owners. Attorney Sean Devereux proposed renaming Asheville in honor of Arthur Ashe, whose ancestors were owned by Samuel Ashe, for whom the city was named. In June 2021, Asheville Mayor Esther Manheimer was one of 11 U.S. mayors to form Mayors Organized for Reparations and Equity (MORE), a coalition of municipal leaders dedicated to starting pilot reparations programs in their cities.

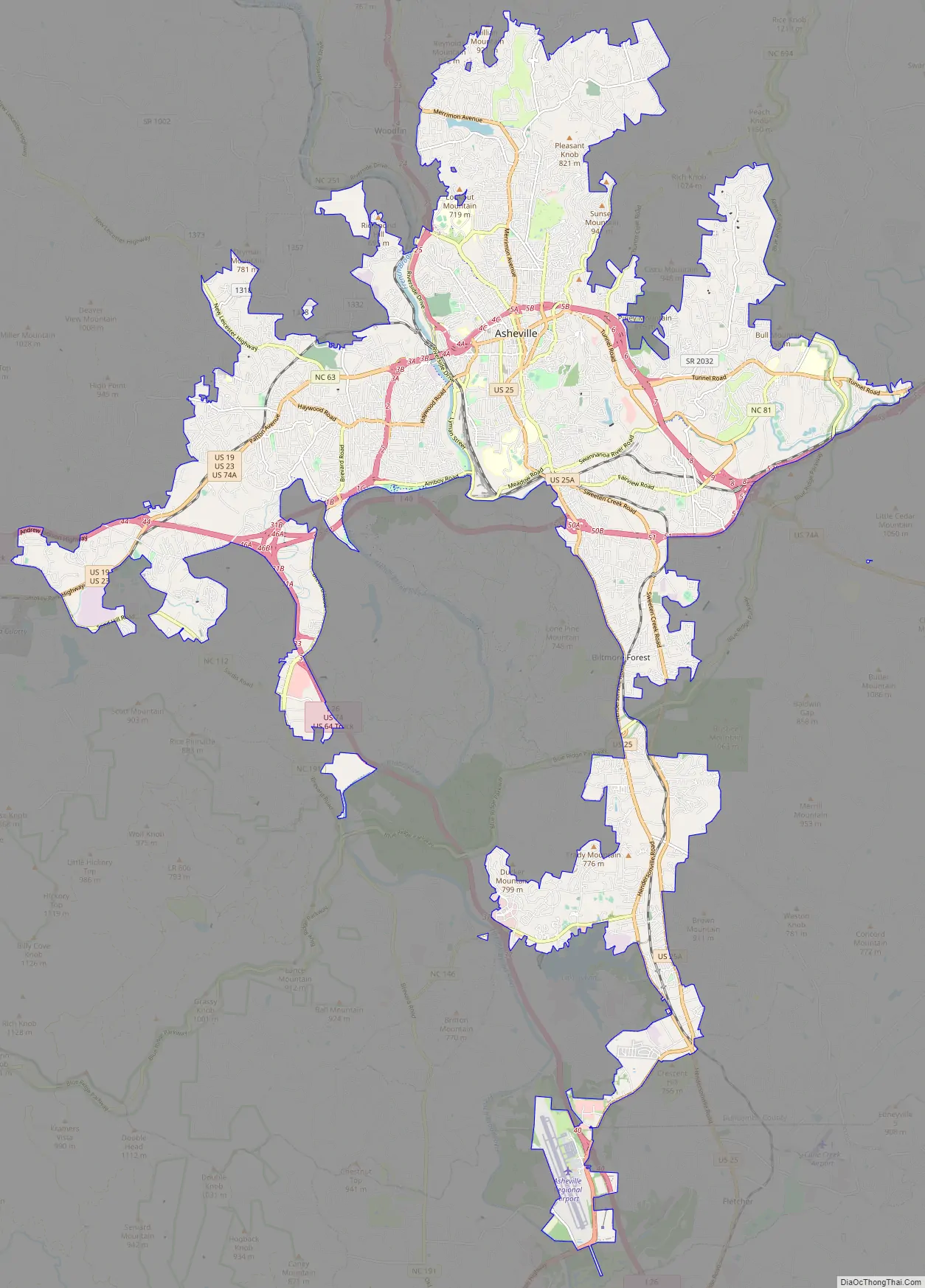

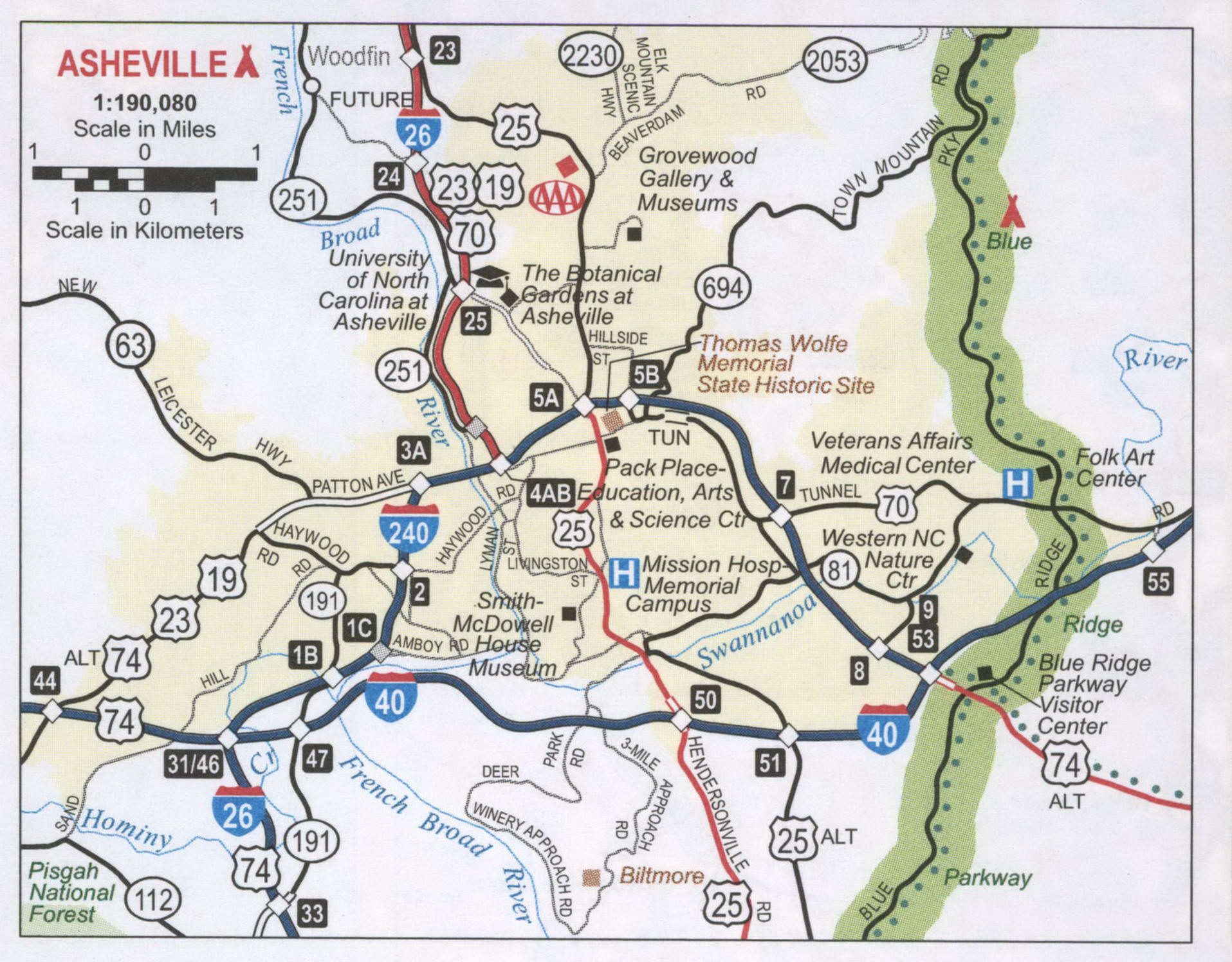

Asheville Road Map

Asheville city Satellite Map

Geography

Asheville is located in the Blue Ridge Mountains at the confluence of the Swannanoa River and the French Broad River. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 45.3 square miles (117.2 km), of which 44.9 square miles (116.4 km) is land and 0.31 square miles (0.8 km), or 0.66%, is water.

Asheville is 68.44 miles west of Hickory, North Carolina, 99.51 northwest of Charlotte, and 133.84 miles southwest of Winston-Salem.

Climate

Asheville features a climate that borders between a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa/Trewartha Do) and an oceanic climate (Koppen Cfb) with noticeably cooler temperatures than the rest of the Piedmont region of the Southeast due to the higher elevation; it is part of USDA Hardiness zone 7a. The area’s summers in particular, though warm, are not as hot as summers in cities farther east in the state, as the July daily average temperature is 73.8 °F (23.2 °C) and there is an average of only 9.4 afternoons with 90 °F (32.2 °C)+ highs annually; The last time a calendar year passed without a single 90 °F (32.2 °C) reading was as recent as 2009. Moreover, warm mornings where the low remains at or above 70 °F or 21.1 °C are much less common than 90 °F or 32.2 °C afternoons. Winters are cool, with a January daily average of 37.1 °F (2.8 °C) and highs remaining at or below freezing on 5.5 afternoons.

Official record temperatures range from −16 °F (−26.7 °C) on January 21, 1985 to 100 °F (37.8 °C) on August 21, 1983; the record cold daily maximum is 4 °F or −15.6 °C on February 4, 1895, while, conversely, the record warm daily minimum is 77 °F or 25 °C on July 17, 1887. Readings as low as 0 °F (−17.8 °C) or as high as 95 °F (35 °C) rarely occur, the last occurrences being January 7, 2014 and July 1, 2012, respectively. The average window for freezing temperatures is October 17 to April 18, allowing a growing season of 181 days.

Asheville is located in the Appalachian temperate rainforest and precipitation is relatively well spread, though the summer months are slightly wetter, and averages 49.6 inches (1,260 mm) annually, but has historically ranged from 22.79 in (579 mm) in 1925 to 79.48 in (2,019 mm) in 2018. Snowfall is sporadic, averaging 10.3 inches or 0.26 metres per winter season, but actual seasonal accumulation varies considerably from one winter to the next; accumulation has ranged from trace amounts in 2011–12 to 48.2 inches or 1.2 metres in 1968–69. Freezing rain often occurs, accompanied by significant disruption. Hail is not uncommon during the spring and summer, accompanied by intense severe thunderstorms but the number of days with thunderstorms varies dramatically from year to year ranging from as low as 15 days in 2008 to as much as 44 in 2018.

Neighborhoods

- North – includes the neighborhoods of Albemarle Park, Beaverdam, Chestnut Hills, Colonial Heights, Five Points, Grove Park, Hillcrest, Kimberly, Klondyke, Montford, and Norwood Park. Chestnut Hill, Grove Park, Lakeview Park, Montford, and Norwood Park neighborhoods are listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Montford and Albemarle Park have been named local historic districts by the Asheville City Council.

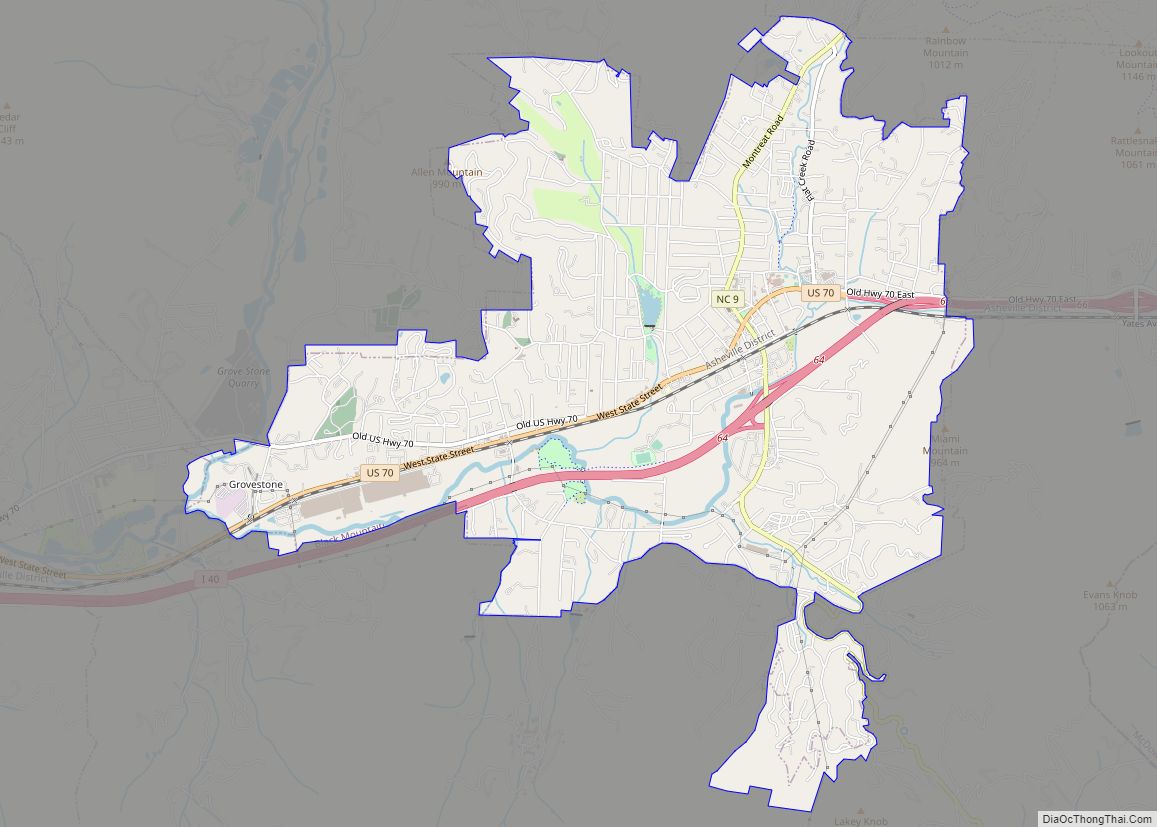

- East – includes the neighborhoods of Kenilworth, Beverly Hills, Chunn’s Cove, Haw Creek, Oakley, Oteen, Reynolds, Riceville, and Town Mountain.

- West – includes the neighborhoods of Camelot, Wilshire Park, Bear Creek, Deaverview Park, Emma, Hi-Alta Park, Lucerne Park, Malvern Hills, Sulphur Springs, Burton Street, Haywood Road, and Pisgah View.

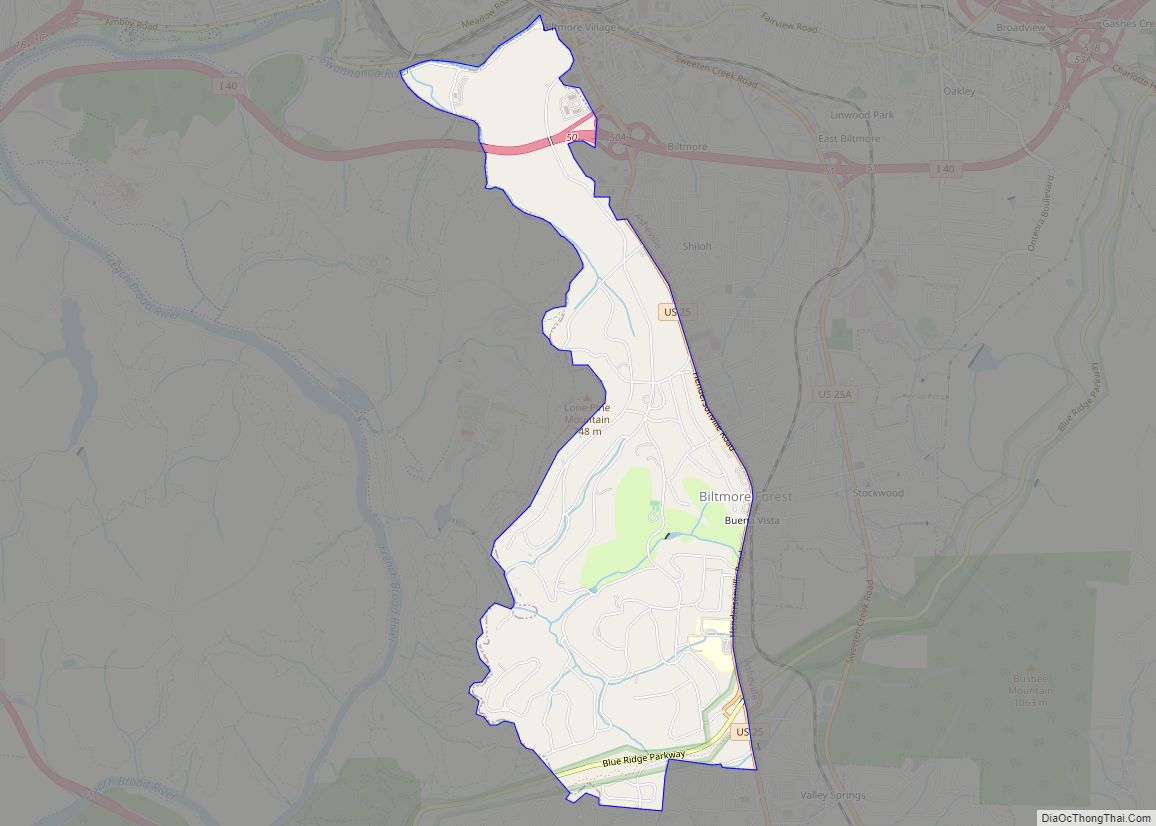

- South – includes the neighborhoods of Ballantree, Biltmore Village, Biltmore Park, Oak Forest, Royal Pines, Shiloh, and Skyland. Biltmore Village has been named a local historic district by the Asheville City Council.

Architecture

Notable architecture in Asheville includes its Art Deco Asheville City Hall, and other unique buildings in the downtown area, such as the Battery Park Hotel, the original of which was 475 feet long with numerous dormers and chimneys; the Neo-Gothic Jackson Building, the first skyscraper on Pack Square; Grove Arcade, one of America’s first indoor shopping malls; and the Basilica of St. Lawrence. The S&W Cafeteria Building is also a fine example of Art Deco architecture in Asheville. The Grove Park Inn is an important example of architecture and design of the Arts and Crafts movement.

Asheville’s recovery from the Depression was slow and arduous. Because of the financial stagnation, there was little new construction and much of the downtown district remained unaltered.

The Montford Area Historic District and other central areas are considered historic districts and include Victorian houses. Biltmore Village, located at the entrance to the famous estate, showcases unique architectural features. It was here that workers stayed during the construction of George Vanderbilt’s estate. The YMI Cultural Center, founded in 1892 by George Vanderbilt in the heart of downtown, is one of the nation’s oldest African-American cultural centers.

Metropolitan area

Asheville is the largest city in the Asheville Metropolitan Statistical Area, which includes Buncombe, Haywood, Henderson, and Madison counties, with a combined 2014 population of 442,316, as estimated by the Census Bureau.

See also

Map of North Carolina State and its subdivision:- Alamance

- Alexander

- Alleghany

- Anson

- Ashe

- Avery

- Beaufort

- Bertie

- Bladen

- Brunswick

- Buncombe

- Burke

- Cabarrus

- Caldwell

- Camden

- Carteret

- Caswell

- Catawba

- Chatham

- Cherokee

- Chowan

- Clay

- Cleveland

- Columbus

- Craven

- Cumberland

- Currituck

- Dare

- Davidson

- Davie

- Duplin

- Durham

- Edgecombe

- Forsyth

- Franklin

- Gaston

- Gates

- Graham

- Granville

- Greene

- Guilford

- Halifax

- Harnett

- Haywood

- Henderson

- Hertford

- Hoke

- Hyde

- Iredell

- Jackson

- Johnston

- Jones

- Lee

- Lenoir

- Lincoln

- Macon

- Madison

- Martin

- McDowell

- Mecklenburg

- Mitchell

- Montgomery

- Moore

- Nash

- New Hanover

- Northampton

- Onslow

- Orange

- Pamlico

- Pasquotank

- Pender

- Perquimans

- Person

- Pitt

- Polk

- Randolph

- Richmond

- Robeson

- Rockingham

- Rowan

- Rutherford

- Sampson

- Scotland

- Stanly

- Stokes

- Surry

- Swain

- Transylvania

- Tyrrell

- Union

- Vance

- Wake

- Warren

- Washington

- Watauga

- Wayne

- Wilkes

- Wilson

- Yadkin

- Yancey

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming