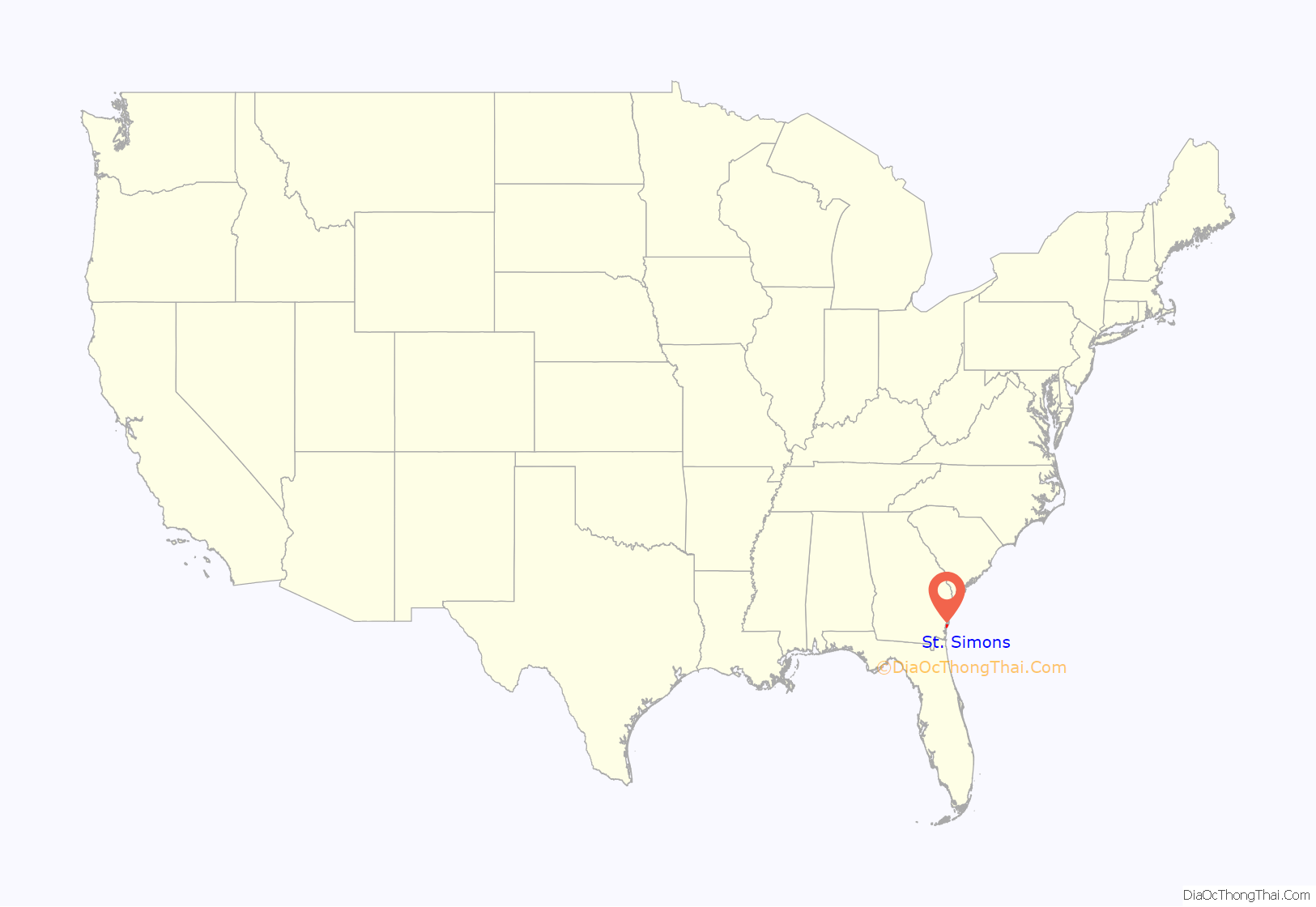

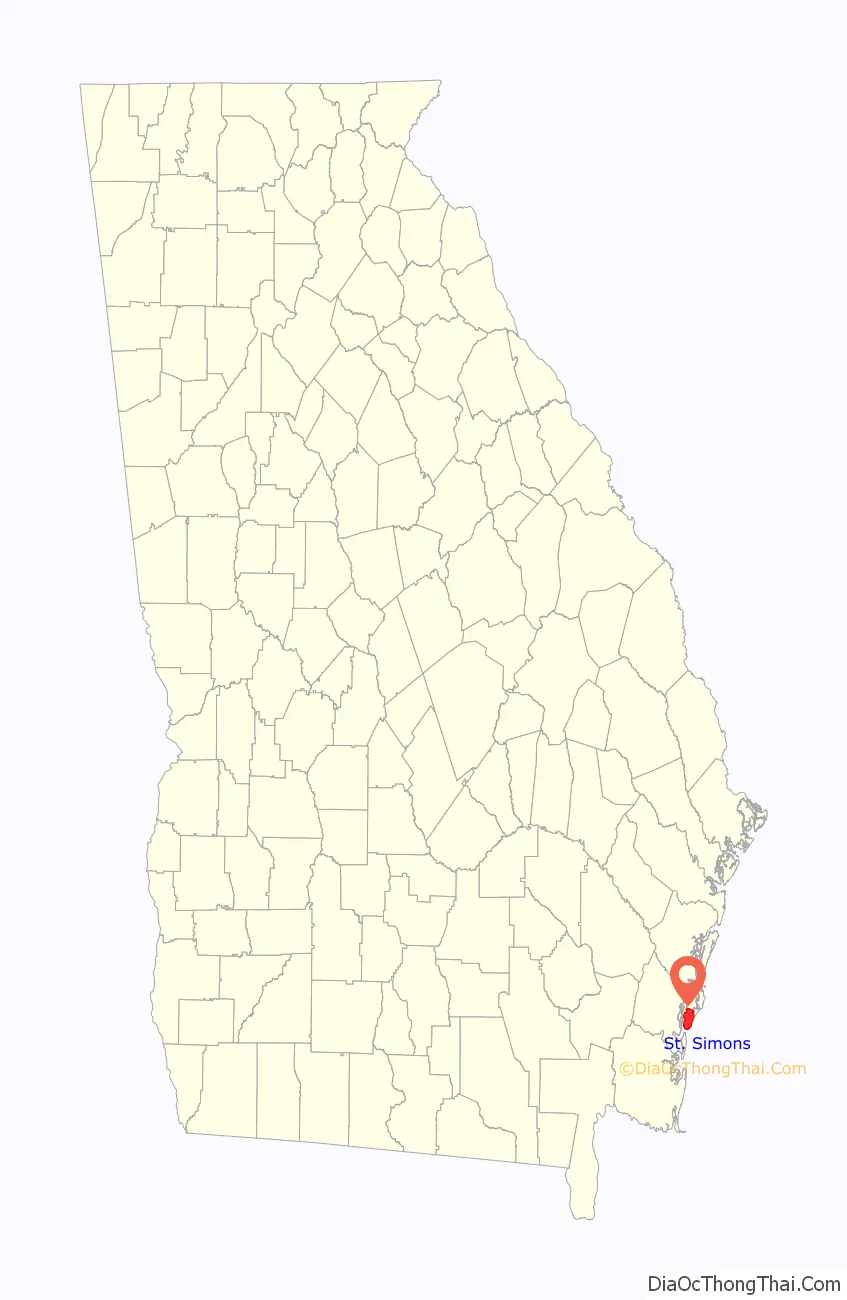

St. Simons Island (or simply St. Simons) is a barrier island and census-designated place (CDP) located on St. Simons Island in Glynn County, Georgia, United States. The names of the community and the island are interchangeable, known simply as “St. Simons Island” or “SSI”, or locally as “The Island”. St. Simons is part of the Brunswick metropolitan statistical area, and according to the 2020 U.S. census, the CDP had a population of 14,982.

Located on the southeast Georgia coast, midway between Savannah and Jacksonville, St. Simons Island is both a seaside resort and residential community. It is the largest of Georgia’s renowned Golden Isles (along with Sea Island, Jekyll Island, and privately owned Little St. Simons Island). Visitors are drawn to the Island for its warm climate, beaches, variety of outdoor activities, shops and restaurants, historical sites, and natural environment.

In addition to its base of permanent residents, the island enjoys an influx of visitors and part-time residents throughout the year. The 2010 census noted that 26.8% of total housing units were for “seasonal, recreational, or occasional use”. The vast majority of commercial and residential development is located on the southern half of the island. Much of the northern half remains marsh or woodland. A large tract of land in the northeast has been converted to a nature preserve containing trails, historical ruins, and an undisturbed maritime forest. The tract, Cannon’s Point Preserve, is open to the public on specified days and hours.

Originally inhabited by tribes of the Creek Nation, the Spaniards, English, and French contested the area of South Georgia that includes St. Simons Island. After securing the Georgia colony, the English cultivated the land for rice and cotton plantations worked by large numbers of enslaved Africans, who created the unique Gullah culture that survives to this day.

The primary mode of travel to the island is by automobile via F.J. Torras Causeway. Malcolm McKinnon Airport (IATA: SSI) serves general aviation on the island.

| Name: | St. Simons CDP |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 57 |

| LSAD Description: | CDP (suffix) |

| State: | Georgia |

| County: | Glynn County |

| Elevation: | 10 ft (3 m) |

| Total Area: | 17.51 sq mi (45.34 km²) |

| Land Area: | 16.48 sq mi (42.69 km²) |

| Water Area: | 1.02 sq mi (2.65 km²) |

| Total Population: | 14,982 |

| Population Density: | 908.94/sq mi (350.95/km²) |

| Area code: | 912 |

| FIPS code: | 1368040 |

| GNISfeature ID: | 0322308 |

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

St. Simons location map. Where is St. Simons CDP?

History

Pre-European contact

Just north of the village on St. Simons Island off Mallery Street is a park of oak trees named St. Simons Park. On the southern edge of the oaks, along a narrow lane, is a low earthen mound where 30 Timucuan Native Americans are buried. The men, women, and children interred there lived in a settlement on the site two centuries before the first European contact.

Cannon’s Point, on the north end of St. Simon’s Island, is an archaeological site that includes a Late Archaic shell ring. The Cannon’s Point site has yielded evidence of occupation by Native Americans since at least as early as the appearance of ceramics in the southeastern United States. Milanich lists the succession of periods at Cannon’s Point as: Sapelo Period (2500–1000 BC); ceramics related to those of the Stallings culture of the Savannah River valley and Orange period of northern Florida; Refuge Period (1000–500 BC); Deptford Periods (500 BC to AD 700); Wilmington Period (700–1000); St. Catherine’s Period (1000–1250); Savannah Periods (1250–1540); Pine Harbor Period (1540–1625), where European artifacts appear in the archaeological record in this period; and Sutherland Bluff Period (1625–1680), where Native American occupation of Cannon’s Point seems to have ended during this period.

Many scholars in the early 20th century identified the people of St. Simons Island as Guale. Hann cites evidence that the people of St. Simons, at least as early as 1580, were part of the Mocama people. Ashley et al. suggest that St. Simons may have been occupied by the Guale people when Europeans arrived in southeastern Georgia in the 16th century and that the original Guale population on St. Simons was displaced from at least the southern part of the island after the Guale rebellion of 1597, and replaced by Timucua speaking Mocama people.

The mission of San Buenaventura de Guadalquini was established on the southern end of St. Simons sometime between 1597 and 1609 (probably near the present-day St. Simons Island Light) and was the northernmost mission in the Mocama area. The Timucua language name for St. Simon’s Island was Guadalquini. The Spanish called it Isla de Ballenas (Isle of Whales). Some Spanish documents called the island Boadalquivi.

Raiders from the Chichimecos (the Spanish name for Westos), Uchise (the Spanish name for Muscogee), and Chiluque (a name the Spanish used for a faction of the Mocamo and for Yamassee) and possibly other nations, aided and supported by the English in the Province of Carolina, attacked Colon (also called San Simon) a village of un-Christianized Yamasee to the north of San Buenaventura on St. Simon Island, in 1680. A force of Spanish soldiers and Native Americans from San Buenaventura went to the aid of Colon, forcing the raiders to withdraw.

In 1683, St. Augustine was attacked by a pirate fleet, and in 1684 missions along what is now the Georgia coast were attacked by Native American allies of the English. The mission of San Buenaventura was ordered to move south and merge with the mission of San Juan del Puerto on the St. Johns River. Before the mission could be moved, pirates returned to the area in the second half of 1684. On hearing of the presence of the pirates, Lorenzo de Santiago, chief of San Buenaventura, moved the people of his village, along with most of their property and stored maize, to the mainland. When the pirates landed at San Buenaventura, they found only ten men under a sub-chief who had been left to guard the village. The San Buenaventura men withdrew to the woods, and the pirates burned the village and mission. After the pirates burned the mission, the people of Guadalquini moved to a site about one league west of San Juan del Puerto on the St. Johns River, where a new mission named Santa Cruz de Guadalquini was established.

Fort Frederica

Fort Frederica, now Fort Frederica National Monument, was built beginning in 1736 as the military headquarters of the Province of Georgia during the early English colonial period. It served as a buffer against Spanish incursion from Florida.

Nearby is the site of the Battle of Gully Hole Creek and Battle of Bloody Marsh, where on July 7, 1742, the British ambushed Spanish troops marching single file through the marsh and routed them from the island. This marked the end of the Spanish efforts to invade Georgia during the War of Jenkins’ Ear.

It was preserved in the 20th century and identified as a national historic site largely by the efforts of Margaret Davis Cates, a resident who contributed much to historic preservation. She helped raise more than $100,000 in 1941 to buy the site of the fort and conduct stabilization and some preservation. It was designated as a National Monument in 1947.

Wesley brothers

In the 1730s, St. Simons served as a sometime home to John Wesley, the young minister of the colony at Savannah. He later returned to England, where in 1738, he founded the evangelical movement of Methodism within the Anglican Church. Wesley performed missionary work at St. Simons but was despondent about failing to bring about conversions. (He wrote that the local inhabitants had more tortures from their environment than he could describe for Hell). In the 1730s, John Wesley’s brother Charles Wesley also did missionary work on St. Simons. In the late eighteenth century, Methodist preachers traveled throughout Georgia as part of the Great Awakening, a religious revival movement led by Methodists and Baptists. A significant impact of the revival was to convert enslaved African-Americans in Georgia (as well as those in the rest of the Thirteen Colonies) to Christianity.

On April 5, 1987, fifty-five St. Simons United Methodist Church members were commissioned, with Bishop Frank Robertson as the first pastor, to begin a new church on the north end of St. Simons Island. This was where John and Charles Wesley had preached and ministered to the people at Fort Frederica. The new church was named Wesley United Methodist Church at Frederica.

American Revolution

In 1778 Colonel Samuel Elbert commanded Georgia’s Continental Army and Navy. On April 15, he learned that four British vessels (the naval vessels HMS Galatea and HMS Hinchinbrook, and the hired vessels Rebecca, and Hatter) from East Florida were sailing in St. Simons Sound. Elbert commanded about 360 troops from the Georgia Continental Battalions at Fort Howe to march to Darien, Georgia. There they boarded three Georgia Navy galleys: Washington, commanded by Captain John Hardy; Lee, commanded by Captain John Cutler Braddock; and Bulloch, commanded by Captain Archibald Hatcher.

On April 18, they entered Frederica River and anchored about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from Fort Frederica. The next day the galleys attacked the British vessels. The Colonial ships were armed with heavier cannons than the British, and the galleys also had a shallow draft and could be rowed. When the wind died down, the British ships had difficulty maneuvering in the restricted waters of the river and sound. Two British ships ran aground, and the crews escaped to their other ships. The battle showed the effectiveness of the galleys in restricted waters over ships designed for the open sea. The victory in the Frederica Naval Action boosted the morale of the colonials in Georgia.

Cotton production

During the plantation era, Saint Simons became a center of cotton production, known for its long-fiber Sea Island Cotton. Nearly the entire island was cleared of trees to make way for several large cotton plantations worked by enslaved Geechee people and their descendants. The plantations of this and other Sea Islands were large, and often the owners stayed on the mainland in Darien and other towns, especially during the summers, because the Island was considered swamp lands. Still, enslaved Geechee people lived on the island and were not allowed to come to the mainland unless accompanied by an enslaver. This season was considered bad for diseases in the lowlands. These enslaved people were held in smaller groups and interacted more with whites. They were also confused with the Gullah tribe from South Carolina. An original slave cabin still stands at the intersection of Demere Rd. and Frederica Rd. at the roundabout.

American Civil War and its aftermath

During the early stages of the war, Confederate troops occupied St. Simons Island to protect its strategic location at the entrance to Brunswick harbor. However, in 1862, Robert E. Lee ordered an evacuation of the island to relocate the soldiers for the defense of Savannah, Georgia. Before departing, they destroyed the lighthouse to prevent its use as a navigation aid by U.S. Navy forces. Most property owners then retreated inland with the people they enslaved, and the U.S. Army occupied the island for the remainder of the war.

Postwar, the island plantations were in ruins, and landowners found it financially unfeasible to cultivate cotton or rice. Most moved inland to pursue other occupations, and the island’s economy remained dormant for several years. Formerly enslaved people established a community in the center of the island known as Harrington.

Since Reconstruction

Saint Simons’ first exports of lumber occurred after the Naval Act of 1794 when timber harvested from two thousand Southern live oak trees from Gascoigne Bluff was used to build the USS Constitution and five other frigates (see six original United States frigates). The USS Constitution is known as “Old Ironsides”, as cannonballs bounced off its hard live oak planking.

The second phase of lumber production on the island began in the late 1870s when mills were constructed in the area surrounding Gascoigne Bluff. The mills supported a vibrant community that lasted until just after the turn of the twentieth century. During this time, lumber from St. Simons was shipped to New York City for use in the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge.

In contrast to the post-Civil War era, the decline of lumber did not open a new period of economic hardship; for a new industry was taking hold on St. Simons Island. As early as the 1870s, summer cottages were being constructed on the island’s south end, and a small village was forming to serve them. Construction of the pier in 1887 brought visitors by boat from Brunswick and south Georgia. The Hotel St. Simons, on the present site of Massengale Park, opened in 1888. About a decade later, two hotels were built near the pier. The arrival of the automobile and the opening of the Torras Causeway in 1924 ensured the continued growth of tourism on St. Simons, the only one of the Golden Isles not privately held. New hotels were built. Roads were constructed, and tourism became the dominant force in the Island’s economy.

On April 8, 1942, World War II became a reality to residents of St. Simons Island when a German U-boat sank two oil tankers in the middle of the night. The blasts shattered windows as far away as Brunswick, and unsubstantiated rumors spread about German soldiers landing on the beaches. Security measures were tightened after the sinkings, and anti-submarine patrols from Glynco Naval Air Station in Brunswick ultimately ended the U-boat threat. During the war, McKinnon Airport became Naval Air Station St. Simons, home to the Navy Radar Training School. The King and Prince Hotel, built in 1941, was used as a training facility and radar station. It was listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places in 2005.

President Jimmy Carter visited the island with his brother Billy Carter in 1977, arriving by Marine One.

During the postwar years, as resort and vacation travel increased, permanent residential development began to take place on St. Simons Island and surrounding mainland communities. The island’s population grew from 1,706 in 1950 to 13,381 by 2000.

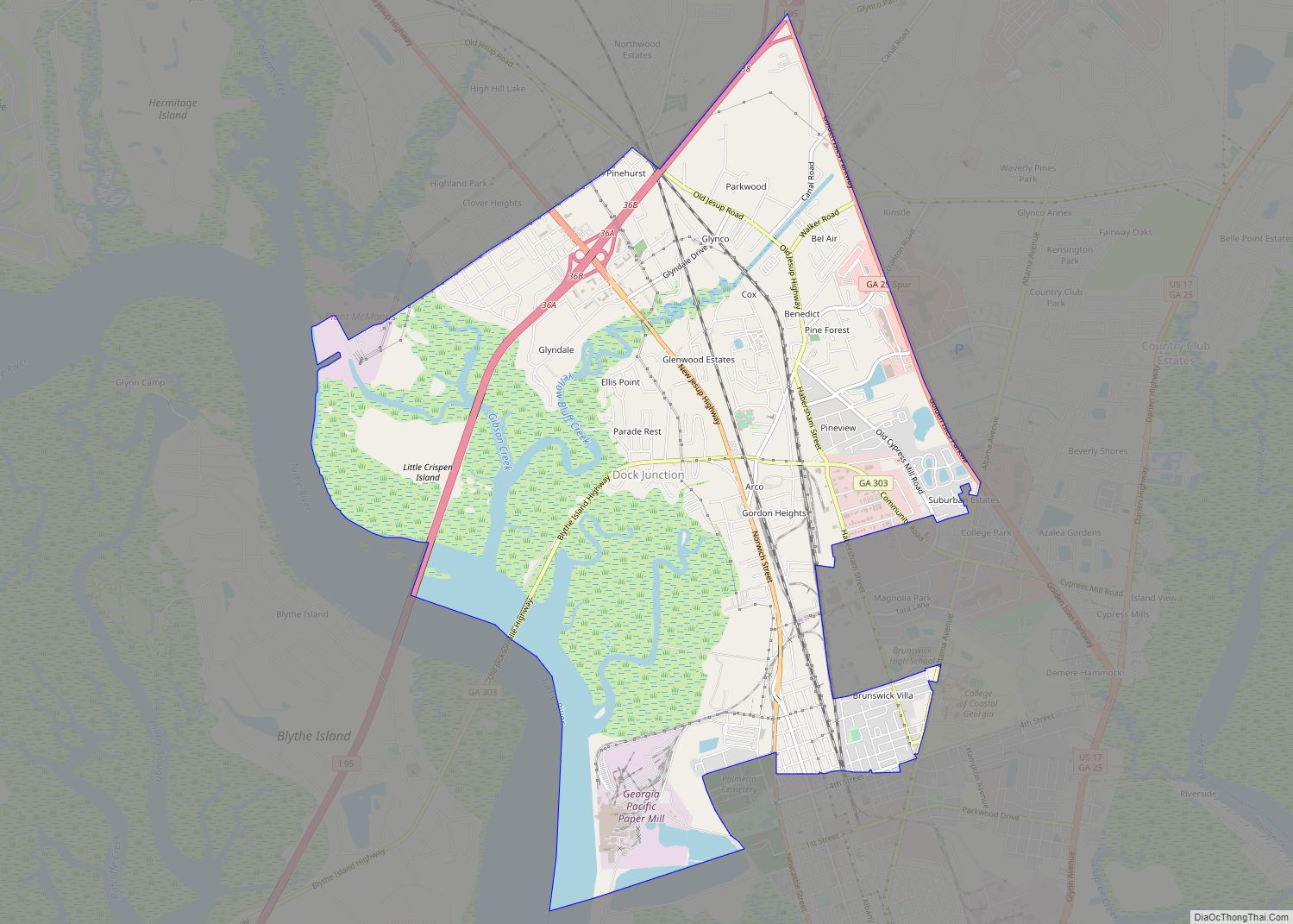

St. Simons Road Map

St. Simons city Satellite Map

Geography

St. Simons Island is part of a cluster of barrier islands and marsh hammocks between the Altamaha River delta to the north, and St. Simons Sound to the south. Sea Island forms the eastern edge of this cluster, with Little St. Simons on the north and the marshes of Glynn plus the Intracoastal Waterway to the west.

St. Simons is located at 31°9′40″N 81°23′13″W / 31.16111°N 81.38694°W / 31.16111; -81.38694 (31.161250, -81.386875), midway between Savannah, Georgia and Jacksonville, Florida, and approximately 12 miles (19 km) east of Brunswick, Georgia, the sole municipality in Glynn County and the county government seat.

Climate

The Köppen Climate Classification System rates the climate of St. Simons Island as humid subtropical. Ocean breezes tend to moderate the island climate, as compared to the nearby mainland. Daytime mean highs in winter range from 61 to 68 °F (16 to 20 °C), with nighttime lows averaging 43 to 52 °F (6 to 11 °C). Summertime mean highs are 88 to 90 °F (31 to 32 °C), with average lows 73 to 75 °F (23 to 24 °C). The average rainfall is 45 inches per year. Rainfall is greatest in August and September when passing afternoon thunderstorms are typical. Accumulation of snow/ice is extremely rare. The last recorded snow on St. Simons was in 1989. The island is located in USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 9a.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 17.7 square miles (46 km), 15.9 square miles (41 km) of which is land and 1.7 square miles (4.4 km) of it (10 percent) is water.

Ecology, vegetation, and wildlife

A diverse and complex ecology exists alongside residential and commercial development on St. Simons Island. The island shares many features common to the chain of sea islands along the southeastern U.S. coast, such as sandy beaches on the ocean side, marshes to the west, and maritime forests inland. Despite centuries of agriculture and development, a canopy of live oaks and other hardwoods draped in Spanish moss continues to shade much of the island. The abundance of food provided by the marshes, estuaries, and vegetation attracts various wildlife on the land, sea, and in the air.

Commonly sighted land and amphibious animals include white-tailed deer, marsh rabbits, raccoons, minks, alligators, armadillos, terrapins and frogs. Overhead, along the shore, and in the marshes, a wide variety of native and migratory shorebirds can be seen year-round. Species include sandpipers, plovers, terns, gulls, herons, egrets, hawks, ospreys, cormorants, white ibis, brown pelicans, and the southern bald eagle.

The area surrounding St. Simons Island and the Altamaha River delta is an important stopover for migrating shorebirds traveling between South America and their spawning grounds in the Canadian arctic. As a result of all this avian activity, Gould’s Inlet and East Beach on St. Simons Island have designated stops on the Colonial Coast Birding Trail.

The waters off St. Simons Island are likewise home to a great variety of sea life, including dolphins, right whales, a wide diversity of gamefish, and the occasional manatee. On late spring and summer nights, loggerhead sea turtles arrive on the beach to lay their eggs. Area naturalists monitor and protect nests, and guided turtle walks are available. Shrimping is still important to the region, and shrimp boats are often seen just off the beaches.

Like most barrier islands, St. Simons Island beaches constantly shift as tides, wind, and storms move tons of sand annually. Along with umbrellas and folding chairs, beach-goers can encounter fast-moving ghost crabs, sand dollars, giant horseshoe crabs, and moving conch shells powered by resident hermit crabs. Sea oats and morning glories cover the dunes along East Beach. Jumping mullet and tiny bait fish populate the coastal waters. Dolphin sightings are common, particularly off the island’s south coast.

Cannon’s Point Preserve

In September 2012, following an 18-month fund-raising effort, the St. Simons Land Trust acquired a 608-acre tract of undeveloped land in the northeast portion of the island. The acreage includes maritime forest, salt marsh, tidal creek, and river shoreline, as well as ancient shell middens and remains of the John Couper plantation of the early 19th century.

The Preserve is open to the public on Saturdays, Sundays, and Mondays, 9 AM-3 PM, for hiking, bicycling, bird-watching, and picnicking. The Preserve also features a launch site for kayaks, canoes, and paddleboards and an observation tower at the north end.

See also

Map of Georgia State and its subdivision:- Appling

- Atkinson

- Bacon

- Baker

- Baldwin

- Banks

- Barrow

- Bartow

- Ben Hill

- Berrien

- Bibb

- Bleckley

- Brantley

- Brooks

- Bryan

- Bulloch

- Burke

- Butts

- Calhoun

- Camden

- Candler

- Carroll

- Catoosa

- Charlton

- Chatham

- Chattahoochee

- Chattooga

- Cherokee

- Clarke

- Clay

- Clayton

- Clinch

- Cobb

- Coffee

- Colquitt

- Columbia

- Cook

- Coweta

- Crawford

- Crisp

- Dade

- Dawson

- Decatur

- DeKalb

- Dodge

- Dooly

- Dougherty

- Douglas

- Early

- Echols

- Effingham

- Elbert

- Emanuel

- Evans

- Fannin

- Fayette

- Floyd

- Forsyth

- Franklin

- Fulton

- Gilmer

- Glascock

- Glynn

- Gordon

- Grady

- Greene

- Gwinnett

- Habersham

- Hall

- Hancock

- Haralson

- Harris

- Hart

- Heard

- Henry

- Houston

- Irwin

- Jackson

- Jasper

- Jeff Davis

- Jefferson

- Jenkins

- Johnson

- Jones

- Lamar

- Lanier

- Laurens

- Lee

- Liberty

- Lincoln

- Long

- Lowndes

- Lumpkin

- Macon

- Madison

- Marion

- McDuffie

- McIntosh

- Meriwether

- Miller

- Mitchell

- Monroe

- Montgomery

- Morgan

- Murray

- Muscogee

- Newton

- Oconee

- Oglethorpe

- Paulding

- Peach

- Pickens

- Pierce

- Pike

- Polk

- Pulaski

- Putnam

- Quitman

- Rabun

- Randolph

- Richmond

- Rockdale

- Schley

- Screven

- Seminole

- Spalding

- Stephens

- Stewart

- Sumter

- Talbot

- Taliaferro

- Tattnall

- Taylor

- Telfair

- Terrell

- Thomas

- Tift

- Toombs

- Towns

- Treutlen

- Troup

- Turner

- Twiggs

- Union

- Upson

- Walker

- Walton

- Ware

- Warren

- Washington

- Wayne

- Webster

- Wheeler

- White

- Whitfield

- Wilcox

- Wilkes

- Wilkinson

- Worth

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming