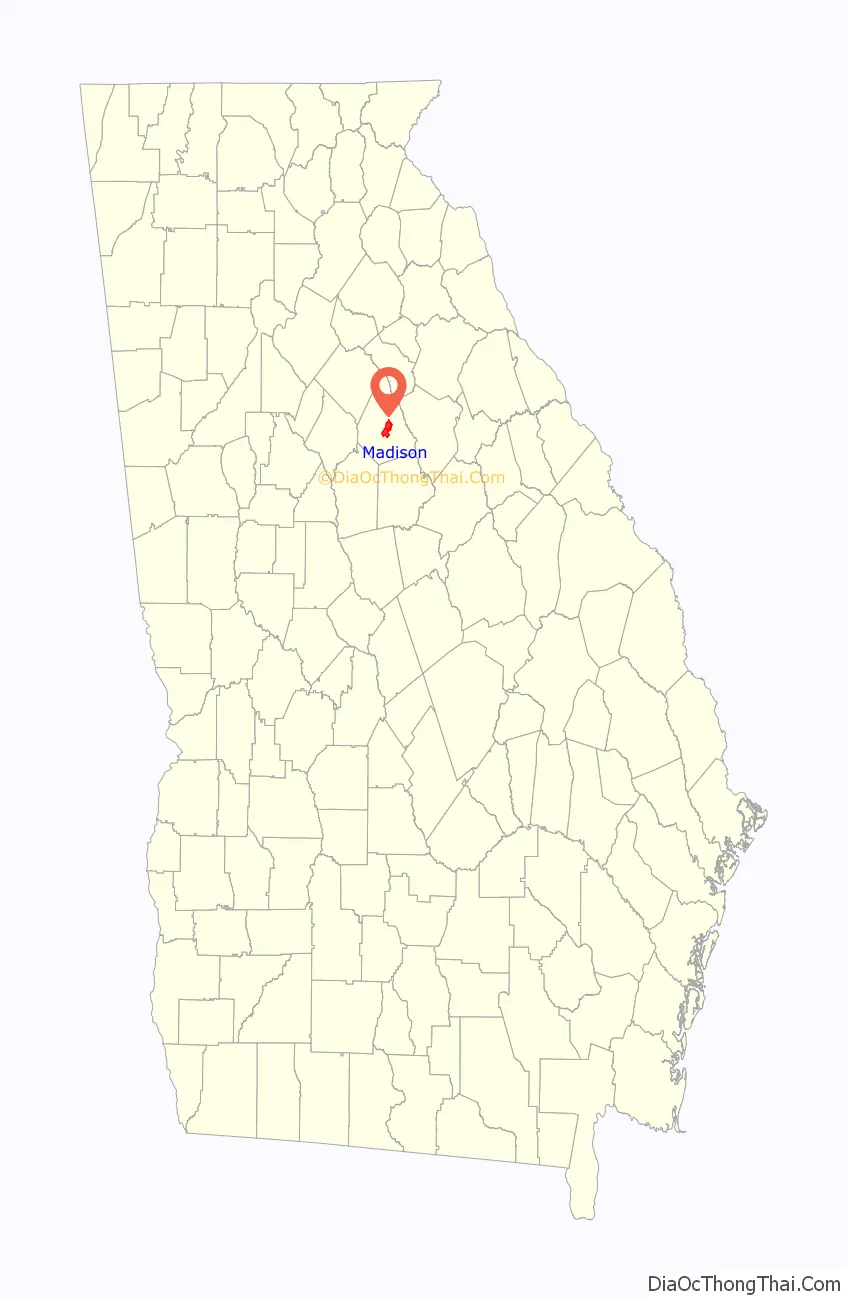

Madison is a city in Morgan County, Georgia, United States. It is part of the Atlanta-Athens-Clarke-Sandy Springs Combined Statistical Area. The population was 4,447 at the 2020 census, up from 3,979 in 2010. The city is the county seat of Morgan County and the site of the Morgan County Courthouse.

The Madison Historic District is one of the largest in the state. Many of the nearly 100 antebellum homes have been carefully restored. Bonar Hall is one of the first of the grand-style Federal homes built in Madison during the town’s cotton-boom heyday from 1840 to 1860.

Budget Travel magazine voted Madison as one of the world’s 16 most picturesque villages.

Madison is featured on Georgia’s Antebellum Trail, and is designated as one of the state’s Historic Heartland cities.

| Name: | Madison city |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 25 |

| LSAD Description: | city (suffix) |

| State: | Georgia |

| County: | Morgan County |

| Incorporated: | December 12, 1809; 213 years ago (1809-12-12) |

| Elevation: | 679 ft (207 m) |

| Total Area: | 8.86 sq mi (22.94 km²) |

| Land Area: | 8.78 sq mi (22.75 km²) |

| Water Area: | 0.07 sq mi (0.19 km²) |

| Total Population: | 4,447 |

| Population Density: | 506.26/sq mi (195.48/km²) |

| ZIP code: | 30650 |

| Area code: | 706 |

| FIPS code: | 1349196 |

| GNISfeature ID: | 0332303 |

| Website: | madisonga.com |

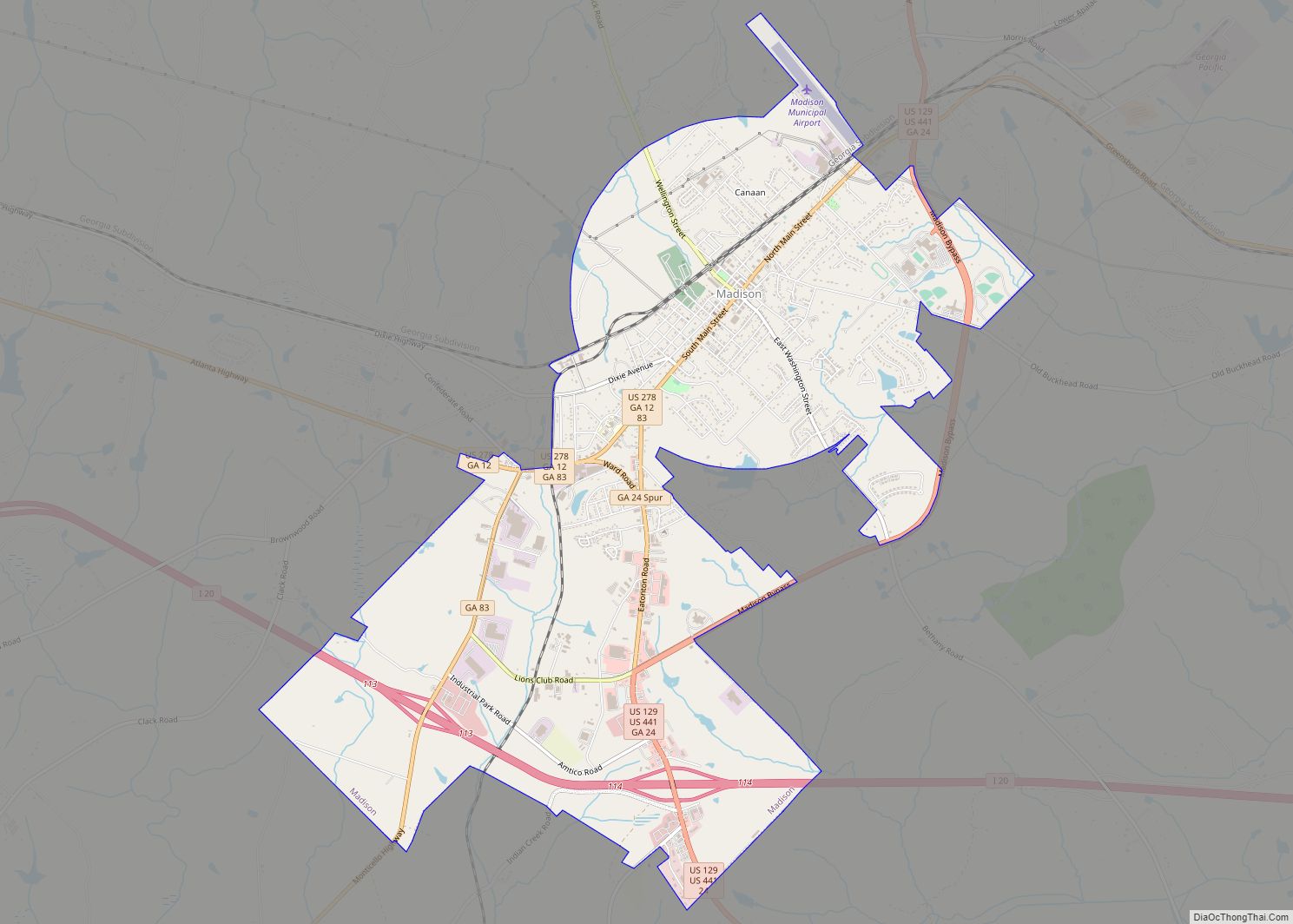

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

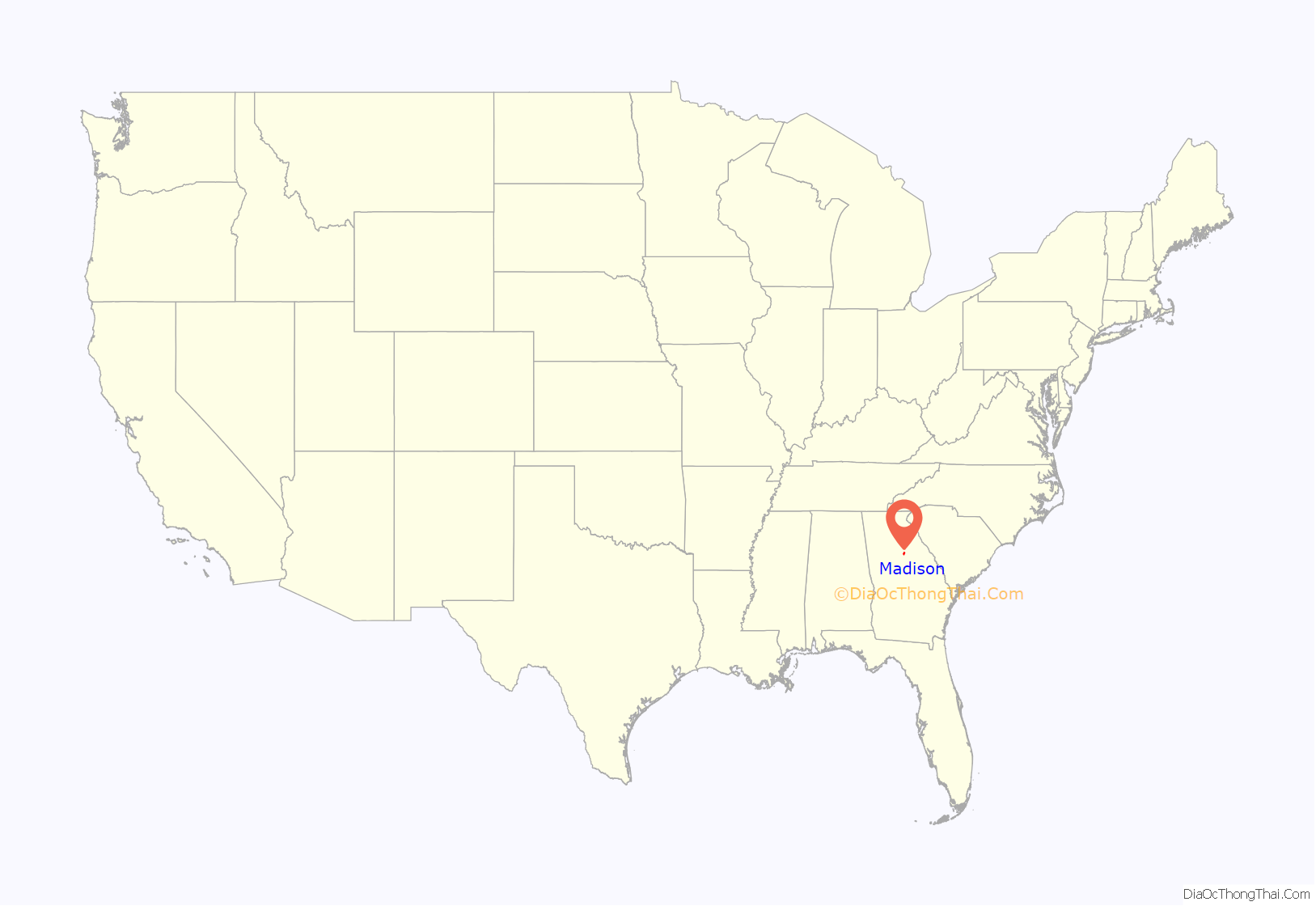

Madison location map. Where is Madison city?

History

Early 19th century

On December 12, 1809, the town, named for 4th United States president, James Madison, was incorporated. Madison was described in an early 19th-century issue of White’s Statistics of Georgia as “the most cultured and aristocratic town on the stagecoach route from Charleston to New Orleans.” An 1849 edition of White’s Statistics stated, “In point of intelligence, refinement, and hospitality, this town acknowledges no superior.”

While many believe that William Tecumseh Sherman spared the town because it was too beautiful to burn during his March to the Sea, the truth is that Madison was home to pro-Union Congressman (later Senator) Joshua Hill. Hill had ties with General Sherman’s brother in the House of Representatives, so his sparing the town was more political than appreciation of its beauty.

Jim Crow era

In 1895 Madison was reported to have an oil mill with a capital of $35,000, a soap factory, a fertilizer factory, four steam ginneries, a mammoth compress, two carriage factories, a furniture factory, a grist and flouringmill, a bottling works, a distillery with a capacity of 120 gallons a day, an ice factory with a capital of $10,500, a canning factory with a capital of $10,000, a bank with a capital of $75,000, surplus $12,000, and a number of small industries operated by individual enterprise. One of the carriage factories was owned and operated by prominent African-American businessman and entrepreneur H. R. Goldwire.

Against the backdrop of this Jim Crow-era prosperity, white Madisonians participated in at least three documented lynchings of African Americans. In February 1890, after a rushed trial involving knife-wielding jurors, Brown Washington, a 15-year-old, was found guilty of the murder of a 9-year-old local white girl. After the verdict, though the sheriff with the governor’s approval called up the Madison Home Guard to protect Washington, “only three militiamen and none of the officers” responded to the order. Washington was thus easily taken from jail by a posse of ten men organized by a “leading local businessman”. Described as “among the best citizens”, they promptly handed him over to a mob of 300+ waiting outside the courthouse. From there, he was taken to a telegraph pole behind a Mr. Poullain’s residence, allowed a prayer, then strung up and shot, his body mutilated by more than a hundred bullets. Afterwards, in the patriarchal exhibition-style common of southern lynchings, a sign was posted on the telegraph pole: “Our women and children will be protected.” His body was not taken down until noon the next day.

According to Brundage’s account of the lynching of Brown Washington in Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 1880-1930:

In the aftermath, though local and state authorities vowed to thoroughly investigate the lynching as well as the Madison Home Guard’s dereliction of duty, just a week later a grand jury was advised by a judge of the superior court of Madison that any investigation would be a waste of time. In addition, the state body charged with investigating the home guard’s non-response reported that their absence had been satisfactorily explained and no tribunal would be convened to investigate the matter.”

Although the local Madisonian newspaper failed to report on the 1890 extra-judicial murder of Mr. Washington, an even earlier first lynching by Madisonians of a man they similarly pulled out of the old stone county jail appears in the contemporary accounts from the Atlanta Constitution.

In 1919, ten years after the erection of a Confederate memorial one block from the newly built Morgan County courthouse, a third lynching occurred in the dark of night a few days before Thanksgiving. This time, citizens skipped the show-trials altogether, opting to travel to the home of Mr. Wallace Baynes in what one paper of the day called an “arresting party”, though no charges against Mr. Baynes were stipulated in the news account. Baynes shot at the party, striking Mr. Frank F. Ozburn of Madison in the head, killing him instantly. In response, the mob outside his home grew to 40-50 men. Despite the arrival of Madison Sheriff C.S. Baldwin, Mr. Baynes was pulled from his home by a rope and shot near the Little River. Afterwards, the sheriff present at the lynching said he could not identify any of the men who came for Mr. Baynes, despite the fact that they arrived in cars and lit up Mr. Baynes’ home with the headlights of their vehicles. In an editorial that argued that mobs in the South were no worse than mobs in the North yet condemned future lynchings, the local Madisonian claimed: “There is not now and perhaps will never be, any friction between the races here.”

The Confederate monument erected in 1909 by the Morgan County Daughters of the Confederacy one block from the courthouse where Mr. Baynes was not afforded a trial was inscribed in part: “NO NATION ROSE/SO WHITE AND FAIR, NONE FELL SO PURE OF CRIME.” In the 1950s the monument was moved to Hill Park, a Madison city property donated by Bell Hill Knight, daughter of Joshua Hill, the aforementioned pro-Union senator who before the Civil War resigned his position rather than support secession. Mrs. Knight, whose husband Captain Gazaway Knight was Commander of the Panola Guards, a Confederate brigade that was organized in Madison, was a staunch member of the Morgan County Daughters of the Confederacy.

Present day

Madison has one of the largest historic districts in the state of Georgia, with visitors coming to see the antebellum architecture of the homes. Allie Carroll Hart was instrumental in establishing Madison’s historical prestige.

According to the Madison Historic Preservation Commission, “The Madison Historic District is listed in the National Register of Historic Places and is Madison’s foremost tourist attraction. Preservation of the district and of each property within its boundary provides for the protection of Madison’s unique historic character and quality environment. Madison’s preservation efforts reflect a nationwide movement to preserve a ‘sense of place’ amid generic modern development.” The Historic Preservation Commission, appointed by Mayor and Council, is charged with protecting the historic character of the district through review of proposed exterior changes.

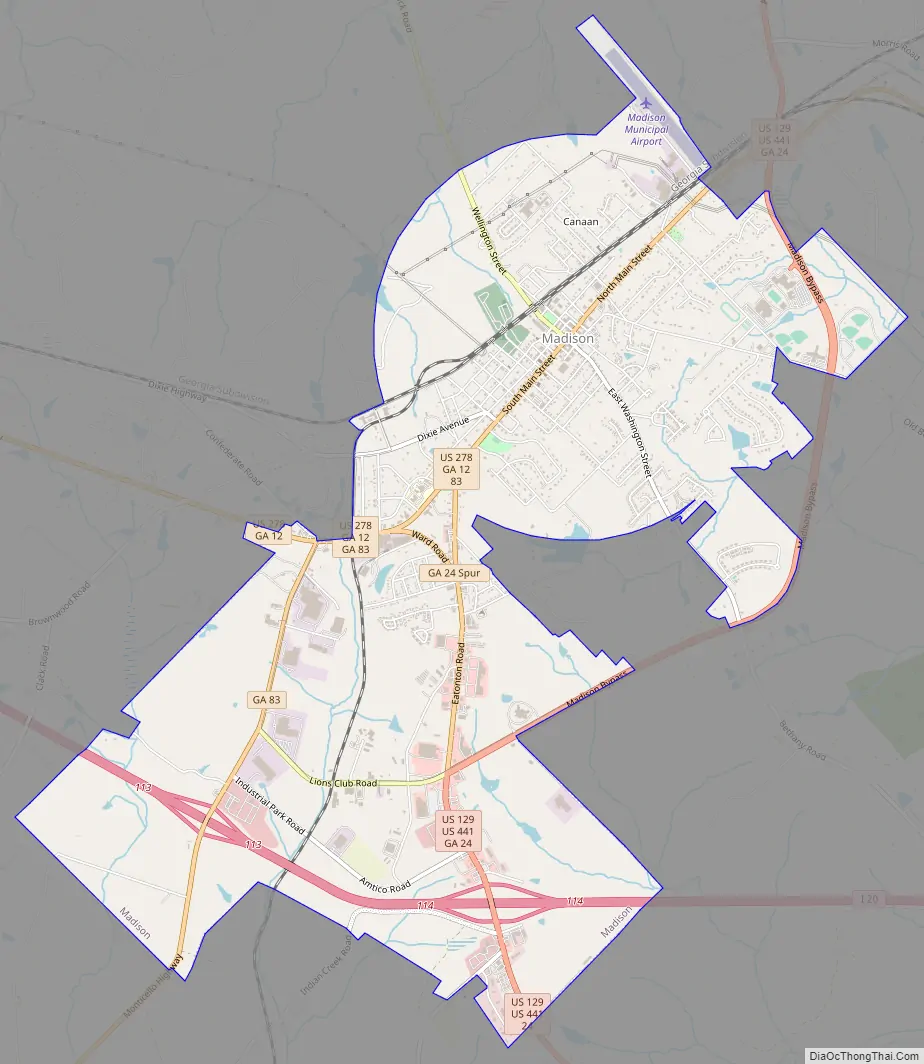

Madison Road Map

Madison city Satellite Map

Geography

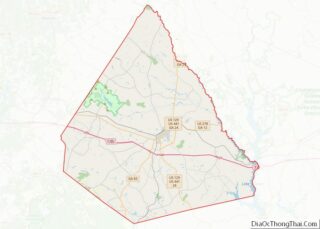

Madison is located in central Morgan County at 33°35′17″N 83°28′21″W / 33.58806°N 83.47250°W / 33.58806; -83.47250 (33.588038, -83.472368). According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 8.9 square miles (23 km), of which 0.07 square miles (0.18 km), or 0.82%, are water.

Madison is situated at an elevation of 691 feet (211 m) on a ridge which traverses Morgan County from the northeast to the southwest. In Madison, the south side of the ridge drains to tributaries of Sugar Creek, which flows southeast to the Oconee River, while the north side drains via Mill Branch to Hard Labor Creek, an east-flowing tributary of the Apalachee River, which continues to the Oconee. The southwest part of the city drains to Little Indian Creek, a tributary of the Little River, which flows to the Oconee north of Milledgeville.

Interstate 20, U.S. Route 129, U.S. Route 441, and U.S. Route 278 pass through Madison. I-20 serves the city from exits 113 and 114, leading east 90 miles (140 km) to Augusta and west 57 miles (92 km) to Atlanta. U.S. 278 runs through the center of the city, leading east 19 miles (31 km) to Greensboro and west 24 miles (39 km) to Covington. U.S. 129/441 run through the city together, leading north 29 miles (47 km) to Athens and south 22 miles (35 km) to Eatonton.

See also

Map of Georgia State and its subdivision:- Appling

- Atkinson

- Bacon

- Baker

- Baldwin

- Banks

- Barrow

- Bartow

- Ben Hill

- Berrien

- Bibb

- Bleckley

- Brantley

- Brooks

- Bryan

- Bulloch

- Burke

- Butts

- Calhoun

- Camden

- Candler

- Carroll

- Catoosa

- Charlton

- Chatham

- Chattahoochee

- Chattooga

- Cherokee

- Clarke

- Clay

- Clayton

- Clinch

- Cobb

- Coffee

- Colquitt

- Columbia

- Cook

- Coweta

- Crawford

- Crisp

- Dade

- Dawson

- Decatur

- DeKalb

- Dodge

- Dooly

- Dougherty

- Douglas

- Early

- Echols

- Effingham

- Elbert

- Emanuel

- Evans

- Fannin

- Fayette

- Floyd

- Forsyth

- Franklin

- Fulton

- Gilmer

- Glascock

- Glynn

- Gordon

- Grady

- Greene

- Gwinnett

- Habersham

- Hall

- Hancock

- Haralson

- Harris

- Hart

- Heard

- Henry

- Houston

- Irwin

- Jackson

- Jasper

- Jeff Davis

- Jefferson

- Jenkins

- Johnson

- Jones

- Lamar

- Lanier

- Laurens

- Lee

- Liberty

- Lincoln

- Long

- Lowndes

- Lumpkin

- Macon

- Madison

- Marion

- McDuffie

- McIntosh

- Meriwether

- Miller

- Mitchell

- Monroe

- Montgomery

- Morgan

- Murray

- Muscogee

- Newton

- Oconee

- Oglethorpe

- Paulding

- Peach

- Pickens

- Pierce

- Pike

- Polk

- Pulaski

- Putnam

- Quitman

- Rabun

- Randolph

- Richmond

- Rockdale

- Schley

- Screven

- Seminole

- Spalding

- Stephens

- Stewart

- Sumter

- Talbot

- Taliaferro

- Tattnall

- Taylor

- Telfair

- Terrell

- Thomas

- Tift

- Toombs

- Towns

- Treutlen

- Troup

- Turner

- Twiggs

- Union

- Upson

- Walker

- Walton

- Ware

- Warren

- Washington

- Wayne

- Webster

- Wheeler

- White

- Whitfield

- Wilcox

- Wilkes

- Wilkinson

- Worth

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming