| Name: | Galveston city |

|---|---|

| LSAD Code: | 25 |

| LSAD Description: | city (suffix) |

| State: | Texas |

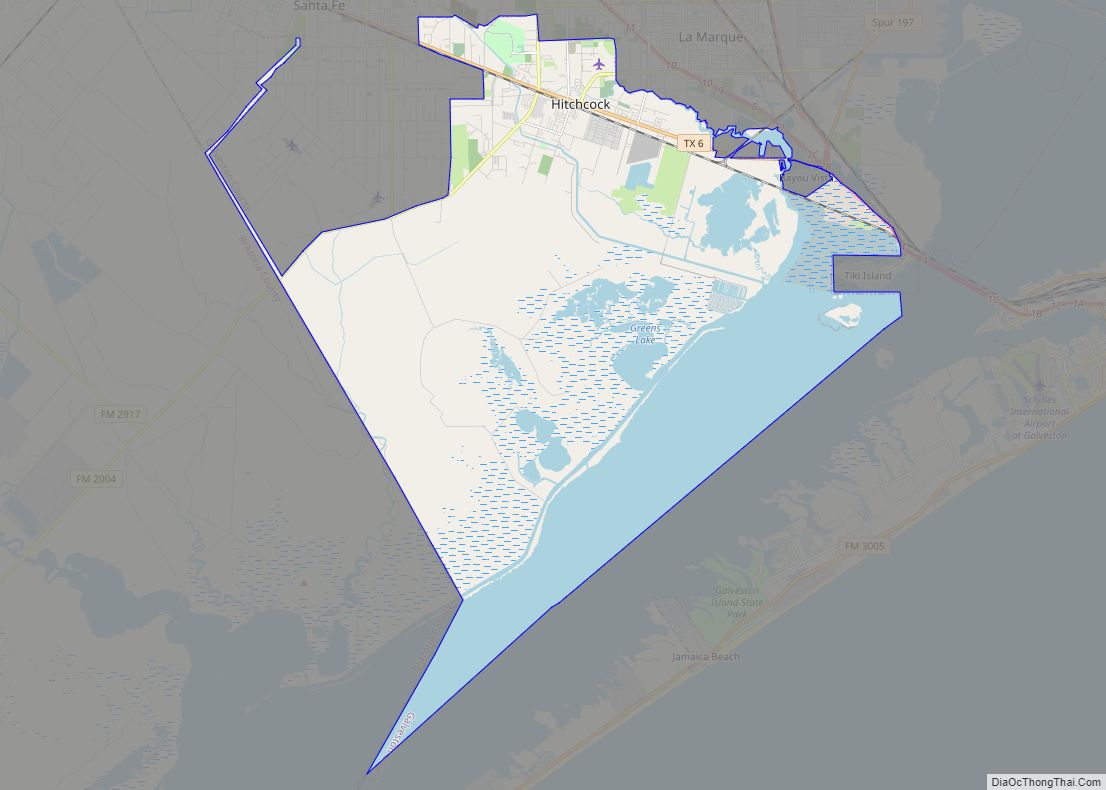

| County: | Galveston County |

| Incorporated: | town incorporated 1839 |

| Elevation: | 7 ft (2 m) |

| Land Area: | 41.05 sq mi (106.33 km²) |

| Water Area: | 170.66 sq mi (442.02 km²) |

| Population Density: | 1,307.9/sq mi (505.0/km²) |

| Area code: | 409 |

| FIPS code: | 4828068 |

| GNISfeature ID: | 1377745 |

| Website: | galvestontx.gov |

Online Interactive Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

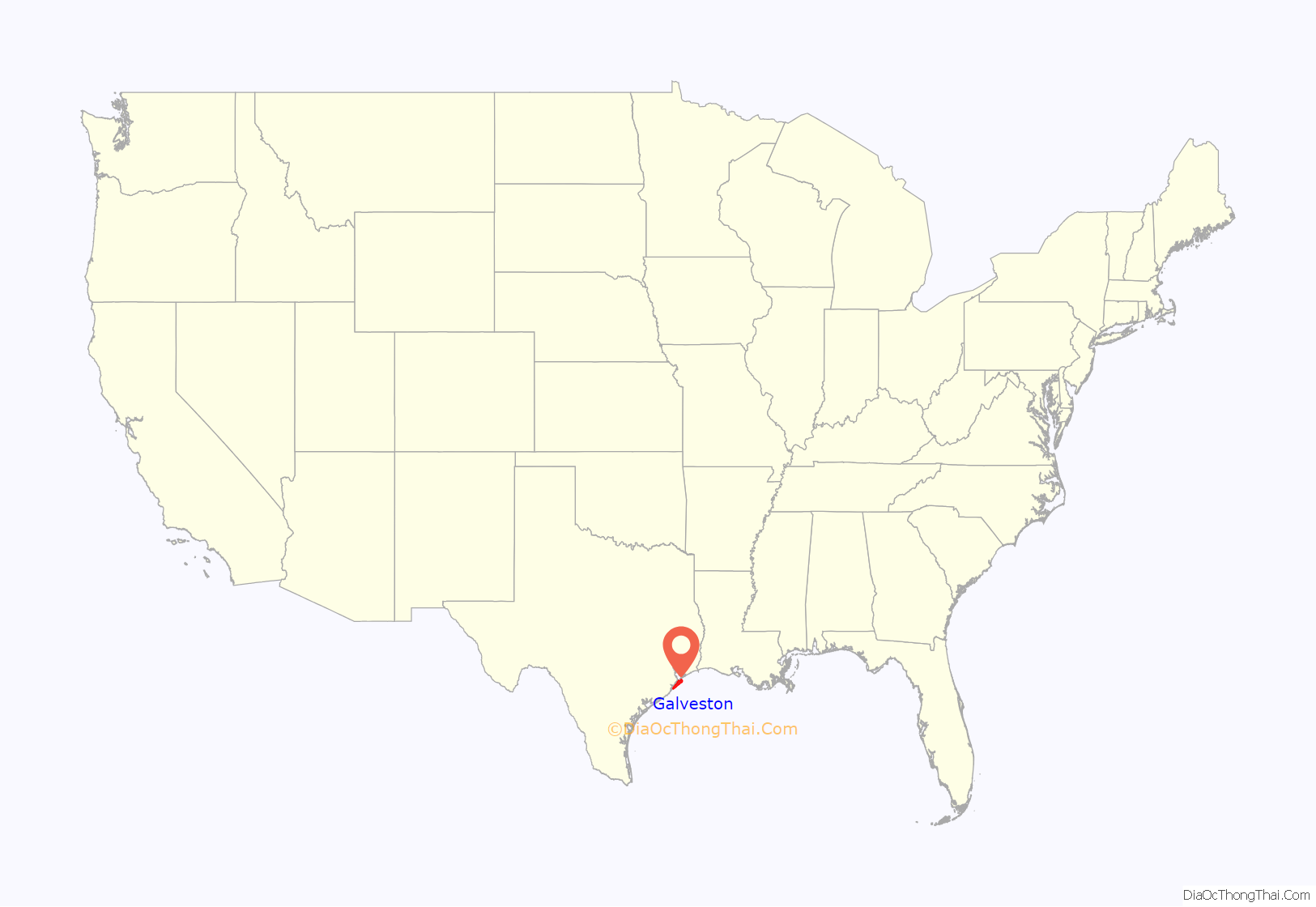

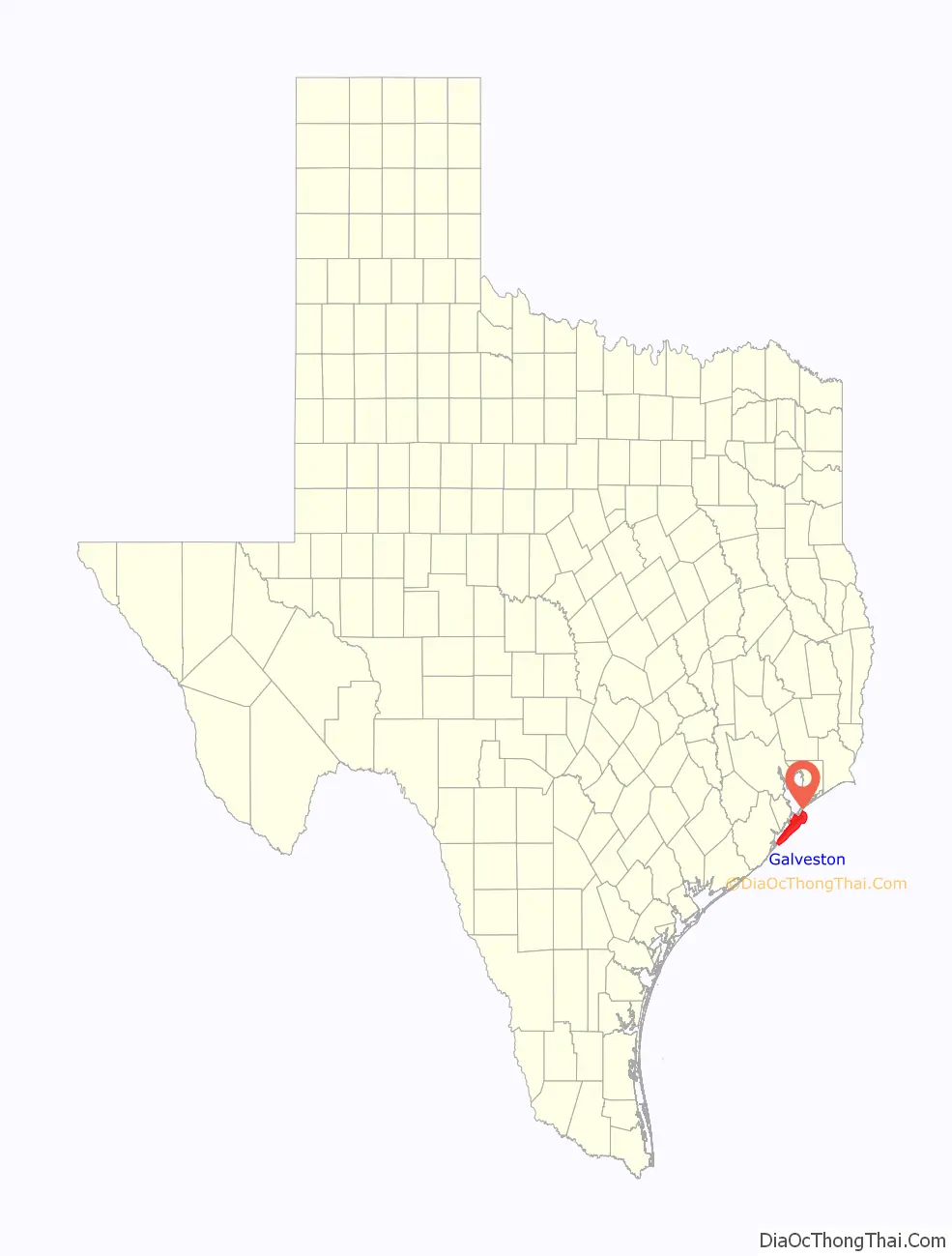

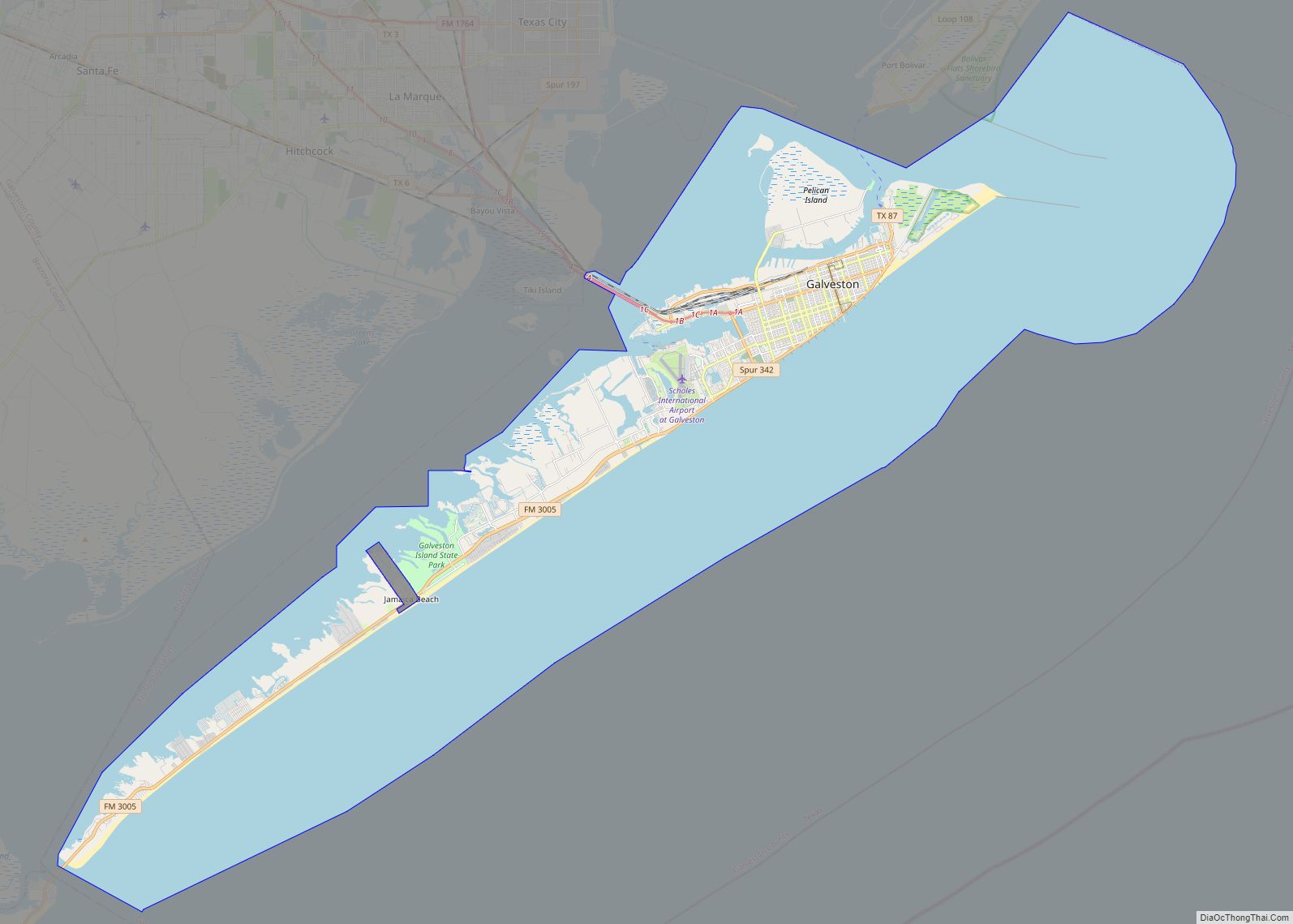

Galveston location map. Where is Galveston city?

History

Exploration and 19th-century development

Indigenous inhabitants of Galveston Island called the island Auia. Though there is no certainty regarding their route and their landings, Cabeza de Vaca and his crew were shipwrecked at a place he called “Isla de Malhado” in November 1528. This could have referred to Galveston Island or San Luis Island. During his charting of the Gulf Coast in 1785, the Spanish explorer José de Evia labeled the water features surrounding the island “Bd. de Galvestown” and “Bahia de Galvestowm” [sic]. He was working under the orders of Bernardo de Gálvez. In his early chart, he calls the western end of the island “Isla de San Luis” and the eastern end “Pt. de Culebras”. Evia did not label the island itself on his map of 1799. Just five years later Alexander von Humboldt borrowed the place names Isla de San Luis, Pte. De Culebras, and Bahia de Galveston. Stephen F. Austin followed his predecessors in the use of “San Luis Island”, but introduced “Galveston” to refer to the little village at the east end of the island. Evidence of the name Galveston Island appears on the 1833 David H. Burr.

The island’s first permanent European settlements were constructed around 1816 by the pirate Louis-Michel Aury to support Mexico’s rebellion against Spain. In 1817, Aury returned from an unsuccessful raid against Spain to find Galveston occupied by the pirate Jean Lafitte. Lafitte organized Galveston into a pirate “kingdom” he called “Campeche”, anointing himself the island’s “head of government”. Lafitte remained in Galveston until 1821, when the United States Navy forced him and his raiders off the island.

In 1825 the Congress of Mexico established the Port of Galveston and in 1830 erected a customs house. Galveston served as the capital of the Republic of Texas when in 1836 the interim president David G. Burnet relocated his government there. In 1836, the French-Canadian Michel Branamour Menard and several associates purchased 4,605 acres (18.64 km) of land for $50,000 to found the town that would become the modern city of Galveston. As Anglo-Americans migrated to the city, they brought along or purchased enslaved African-Americans, some of whom worked domestically or on the waterfront, including on riverboats.

In 1839, the City of Galveston adopted a charter and was incorporated by the Congress of the Republic of Texas. The city was by then a burgeoning port of entry and attracted many new residents in the 1840s and later among the flood of German immigrants to Texas, including Jewish merchants. Together with ethnic Mexican residents, these groups tended to oppose slavery, support the Union during the Civil War, and join the Republican Party after the war.

During this expansion, the city had many “firsts” in the state, with the founding of institutions and adoption of inventions: post office (1836), naval base (1836), Texas chapter of a Masonic order (1840); cotton compress (1842), Catholic parochial school (Ursuline Academy) (1847), insurance company (1854), and gas lights (1856).

During the American Civil War, Confederate forces under Major General John B. Magruder attacked and expelled occupying Union troops from the city in January 1863 in the Battle of Galveston. On June 19, 1865, two months after the end of the war and almost three years after the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, General Gordon Granger of the Union Army informed the enslaved people of Texas that they were now free. This news was transmitted via General Order No. 3, an event now commemorated on the federal holiday of Juneteenth.

In 1867 Galveston suffered a yellow fever epidemic; about 1800 people died in the city. These occurred in waterfront and river cities throughout the 19th century, as did cholera epidemics.

The city’s progress continued through the Reconstruction era with numerous “firsts”: construction of the opera house (1870), and orphanage (1876), and installation of telephone lines (1878) and electric lights (1883). Having attracted freedmen from rural areas, in 1870 the city had a black population that totaled 3,000, made up mostly of former slaves but also by persons who were free men of color and educated before the war. Blacks comprised nearly 25% of the city’s population of 13,818 that year.

During the post–Civil War period, leaders such as George T. Ruby and Norris Wright Cuney, who headed the Texas Republican Party and promoted civil rights for freedmen, helped to dramatically improve educational and employment opportunities for blacks in Galveston and in Texas. Cuney established his own business of stevedores and a union of black dockworkers to break the white monopoly on dock jobs. Galveston was a cosmopolitan city and one of the more successful during Reconstruction; the Freedmen’s Bureau was headquartered here. German families sheltered teachers from the North, and hundreds of freedmen were taught to read. Its business community promoted progress, and immigrants stayed after arriving at this port of entry.

By the end of the 19th century, the city of Galveston had a population of 37,000. Its position on the natural harbor of Galveston Bay along the Gulf of Mexico made it the center of trade in Texas. It was one of the nation’s largest cotton ports, in competition with New Orleans. Throughout the 19th century, the port city of Galveston grew rapidly and the Strand was considered the region’s primary business center. For a time, the Strand was known as the “Wall Street of the South”. In the late 1890s, the government constructed Fort Crockett defenses and coastal artillery batteries in Galveston and along the Bolivar Roads. In February 1897, the USS Texas (nicknamed Old Hoodoo), the first commissioned battleship of the United States Navy, visited Galveston. During the festivities, the ship’s officers were presented with a $5,000 silver service, adorned with various Texas motifs, as a gift from the state’s citizens.

Hurricane of 1900 and recovery

On September 8, 1900, the island was struck by a devastating hurricane. This event holds the record as the United States’ deadliest natural disaster. The city was devastated, and an estimated 6,000 to 8,000 people on the island were killed. Following the storm, a 10-mile (16 km) long, 17 foot (5.2 m) high seawall was built to protect the city from floods and hurricane storm surges. A team of engineers including Henry Martyn Robert (Robert’s Rules of Order) designed the plan to raise much of the existing city to a sufficient elevation behind a seawall so that confidence in the city could be maintained.

The city developed the city commission form of city government, known as the “Galveston Plan”, to help expedite recovery.

Despite attempts to draw investment to the city after the hurricane, Galveston never returned to its levels of national importance or prosperity. Development was also hindered by the construction of the Houston Ship Channel, which brought the Port of Houston into competition with the natural harbor of the Port of Galveston for sea traffic. Finally, the Seawall itself created an insurmountable problem: passive erosion resulting in the gradual disappearance of the once-wide beach and the resort business with it. “Within twenty years, the city had lost one hundred yards of sand. People who once watched auto racing on a wide beach were left with a narrow strip of sand at low tide and a gloomy vista of waves on rocks when the tide was high.”

To further her recovery, and rebuild her population, Galveston actively solicited immigration. Through the efforts of Rabbi Henry Cohen and Congregation B’nai Israel, Galveston became the focus of an immigration plan called the Galveston Movement that, between 1907 and 1914, diverted roughly 10,000 Eastern European Jewish immigrants from the usual destinations of the crowded cities of the Northeastern United States. Additionally numerous other immigrant groups, including Greeks, Italians and Russian Jews, came to the city during this period. This immigration trend substantially altered the ethnic makeup of the island, as well as many other areas of Texas and the western U.S.

Though the storm stalled economic development and the city of Houston developed as the region’s principal metropolis, Galveston economic leaders recognized the need to diversify from the traditional port-related industries. In 1905 William Lewis Moody, Jr. and Isaac H. Kempner, members of two of Galveston’s leading families founded the American National Insurance Company. Two years later, Moody established the City National Bank, which would become the Moody National Bank.

During the 1920s and 1930s, the city re-emerged as a major tourist destination. Under the influence of Sam Maceo and Rosario Maceo, the city exploited the prohibition of liquor and gambling in clubs like the Balinese Room, which offered entertainment to wealthy Houstonians and other out-of-towners. Combined with prostitution, which had existed in the city since the Civil War, Galveston became known as the “sin city” of the Gulf. Galvestonians accepted and supported the illegal activities, often referring to their island as the “Free State of Galveston”. The island had entered what would later become known as the “open era”.

The 1930s and 1940s brought much change to the Island City. During World War II, the Galveston Municipal Airport, predecessor to Scholes International Airport, was re-designated a U.S. Army Air Corps base and named “Galveston Army Air Field”. In January 1943, Galveston Army Air Field was officially activated with the 46th Bombardment Group serving an anti-submarine role in the Gulf of Mexico. In 1942, William Lewis Moody, Jr., along with his wife Libbie Shearn Rice Moody, established the Moody Foundation, to benefit “present and future generations of Texans”. The foundation, one of the largest in the United States, would play a prominent role in Galveston during later decades, helping to fund numerous civic and health-oriented programs.

After World War II

The end of the war drastically reduced military investment in the island. Increasing enforcement of gambling laws and the growth of Las Vegas, Nevada, as a competitive center of gambling and entertainment put pressure on the gaming industry on the island. Finally in 1957, Texas Attorney General Will Wilson and the Texas Rangers began a massive campaign of raids that disrupted gambling and prostitution in the city. As these vice industries crashed, so did tourism, taking the rest of the Galveston economy with it. Neither the economy nor the culture of the city was the same afterward.

In 1947, buildings in the city were damaged when a ship carrying 2,200 tons of ammonium nitrate exploded at the nearby Port of Texas City, in what became known as the Texas City disaster.

The island’s economy began a long stagnation. Many businesses relocated off the island during this period, but health care, insurance, and financial industries continue to be strong contributors to the economy. By 1959, the city of Houston had long outpaced Galveston in population and economic growth. Beginning in 1957, the Galveston Historical Foundation began its efforts to preserve historic buildings. The 1966 book The Galveston That Was helped encourage the preservation movement. Restoration efforts financed by motivated investors, notably Houston businessman George P. Mitchell, gradually developed the Strand Historic District and reinvented other areas. A new, family-oriented tourism emerged in the city over many years.

In September 1961, Hurricane Carla struck the city, generating an F4 tornado that killed eight and injured 200.

With the 1960s came the expansion of higher education in Galveston. Already home to the University of Texas Medical Branch, the city got a boost in 1962 with the creation of the Texas Maritime Academy, predecessor of Texas A&M University at Galveston; and by 1967, a community college, Galveston College, had been established.

In the 2000s, property values rose after expensive projects were completed, and demand for second homes by the wealthy increased. It has made it difficult for middle-class workers to find affordable housing on the island.

Hurricane Ike made landfall on Galveston Island in the early morning of September 13, 2008, as a category-2 hurricane with winds of 110 miles per hour. Damage was extensive to buildings along the seawall.

After the storm, the island was rebuilt with investments in tourism and shipping, and continued emphasis on higher education and health care, notably the addition of the Galveston Island Historic Pleasure Pier and the replacement of the bascule-type drawbridge on the railroad causeway with a vertical-lift-type drawbridge to allow heavier freight.

Galveston Road Map

Galveston city Satellite Map

Geography

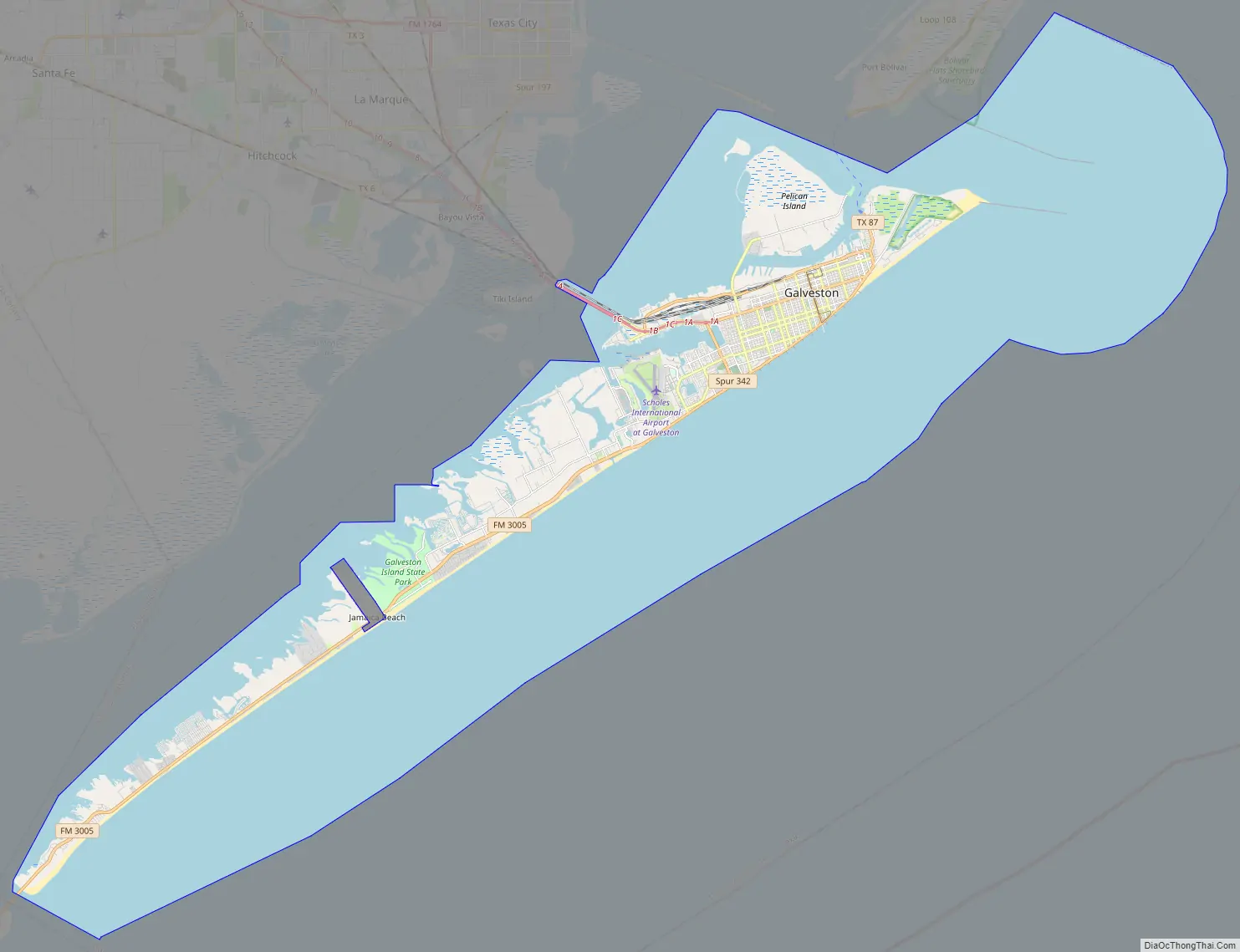

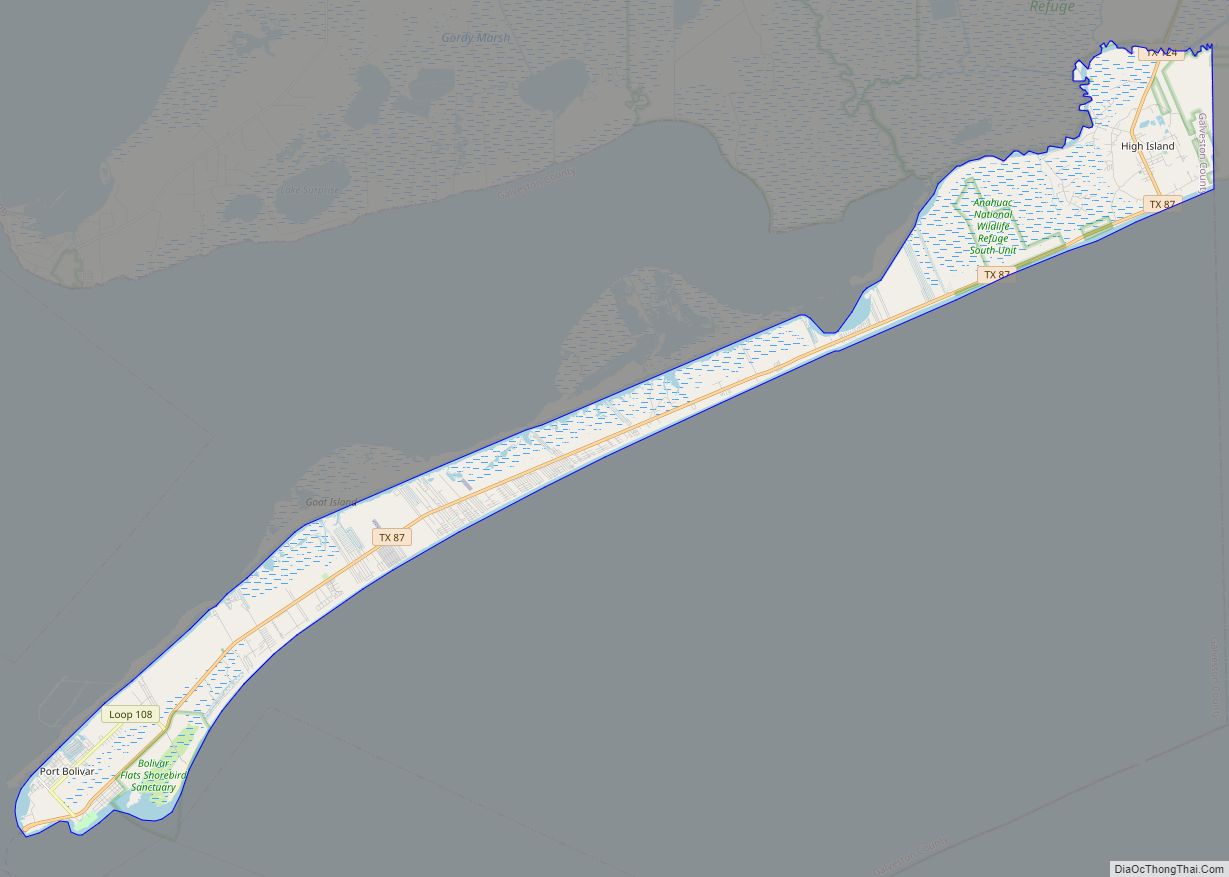

The city of Galveston is situated on Galveston Island, a barrier island off the Texas Gulf coast near the mainland coast. Made up of mostly sand-sized particles and smaller amounts of finer mud sediments and larger gravel-sized sediments, the island is unstable, affected by water and weather, and can shift its boundaries through erosion.

The city is about 45 miles (72 km) southeast of downtown Houston. The island is oriented generally northeast-southwest, with the Gulf of Mexico on the east and south, West Bay on the west, and Galveston Bay on the north. The island’s main access point from the mainland is the Interstate Highway 45 causeway that crosses West Bay on the island’s northeast side.

A deepwater channel connects Galveston’s harbor with the Gulf and the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 209.3 square miles (542.2 km), of which 41.2 square miles (106.8 km) are land and 168.1 square miles (435.4 km), or 80.31%, are water. The island is 50 miles (80 km) southeast of Houston.

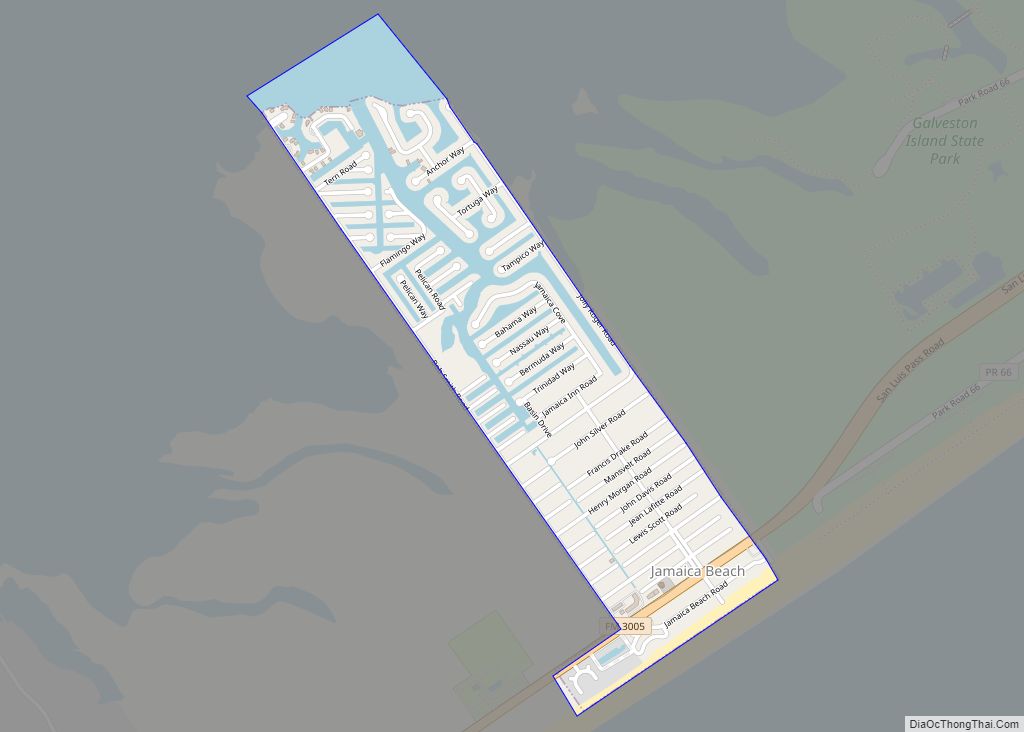

The western portion of Galveston is referred to as the “West End”, roughly corresponding to the area west of the western end of the seawall. Communities in eastern Galveston (the area east of the western end of the seawall) include Havre Lafitte, Offats Bayou, Central City, Fort Crockett, Bayou Shore, Lasker Park, Carver Park, Kempner Park, Old City/Central Business District, San Jacinto, East End, and Lindale. As of 2009 many residents of the west end use golf carts as transportation to take them to and from residential houses, the Galveston Island Country Club, and stores. In 2009, Chief of Police Charles Wiley said he believed golf carts should be prohibited outside golf courses, and West End residents campaigned against any ban on their use.

In 2011 Rice University released a study, “Atlas of Sustainable Strategies for Galveston Island”, which argued the West End of Galveston was quickly eroding and the city should reduce construction and/or population in that area. It recommended against any rebuilding of the West End in the event of damage from another hurricane.

Historic districts

Galveston is home to six historic districts with over 60 structures listed representing architectural significance in the National Register of Historic Places. The Silk Stocking National Historic District, between Broadway and Seawall Boulevard and bounded by Ave. K, 23rd St., Ave. P, and 26th St., contains a collection of historic homes constructed from the Civil War through World War II. The East End Historic District on both sides of Broadway and Market Streets, contains 463 buildings. Other historic districts include Cedar Lawn, Denver Court and Fort Travis.

The Strand National Historic Landmark District is a National Historic Landmark District of mainly Victorian era buildings that have been adapted for use as restaurants, antique stores, historical exhibits, museums and art galleries. The area is a major tourist attraction for the island city. It is the center for two very popular seasonal festivals. It is widely considered the island’s shopping and entertainment center. Today, “the Strand” is generally used to refer to the five-block business district between 20th and 25th streets in downtown Galveston, near the city’s wharf.

Oleander City

Since the early 20th century, Galveston has been popularly known as the ‘Oleander City’ because of a long history of cultivating Nerium oleander, a subtropical evergreen shrub which thrives on the island. Oleanders are a defining feature of the city; when flowering (between April and October) they add masses of color to local gardens, parks, and streets. Thousands were planted in the recovery following the Hurricane of 1900 and Galvestonians continue to treasure the plant for its low water needs, tolerance of heat, salt spray and sandy soils. This makes them especially resistant to the after-effects of hurricanes and tropical storms. Galveston is reputed to have the most diverse range of Oleander cultivars in the world, numbering over 100, with many varieties developed in the city and named after prominent Galvestonians. In 2005 the month of May was declared “Oleander Month” by the City of Galveston and there are also Oleander-themed tours of the city exploring the history of the plant on the island. Since 1967 the International Oleander Society has operated in Galveston, which promotes the cultivation of the plant, organizes an Oleander festival every spring and maintains a commemorative Oleander garden in the city.

Architecture

Galveston contains a large and historically significant collection of 19th-century buildings in the United States. Galveston’s architectural preservation and revitalization efforts over several decades have earned national recognition.

Located in the Strand District, the Grand 1894 Opera House is a restored historic Romanesque Revival style Opera House that is currently operated as a not-for-profit performing arts theater. The Bishop’s Palace, also known as Gresham’s Castle, is an ornate Victorian house located on Broadway and 14th Street in the East End Historic District of Galveston, Texas. The American Institute of Architects listed Bishop’s Palace as one of the 100 most significant buildings in the United States, and the Library of Congress has classified it as one of the fourteen most representative Victorian structures in the nation.

The Galvez Hotel is a historic hotel that opened in 1911. The building was named the Galvez, honoring Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid, Count of Gálvez, for whom the city was named. The hotel was added to the National Register of Historic Places on April 4, 1979. The Michel B. Menard House, built in 1838 and the oldest surviving structure in Galveston, is designed in the Greek revival style. In 1880, the house was bought by Edwin N. Ketchum who was police chief of the city during the 1900 Storm. The Ketchum family owned the home until the 1970s. Ashton Villa, a red-brick Victorian Italianate home, was constructed in 1859 by James Moreau Brown. One of the first brick structures in Texas, it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is a recorded Texas Historic Landmark. The structure is also the site of what was to become the holiday known as Juneteenth, where on June 19, 1865, Union General Gordon Granger, standing on its balcony, read the contents of “General Order No. 3”, thereby emancipating all slaves in the state of Texas.

St. Joseph’s Church was built by German immigrants in 1859–1860 and is the oldest wooden church building in Galveston and the oldest German Catholic Church in Texas. The church was dedicated in April 1860, to St. Joseph, the patron saint of laborers. The building is a wooden gothic revival structure, rectangular with a square bell tower with trefoil window. The U.S. Custom House began construction in 1860 and was completed in 1861. The Confederate Army occupied the building during the American Civil War, In 1865, the Custom House was the site of the ceremony officially ending the Civil War.

Galveston’s modern architecture include the American National Insurance Company Tower (One Moody Plaza), San Luis Resort South and North Towers, The Breakers Condominiums, The Galvestonian Resort and Condos, One Shearn Moody Plaza, US National Bank Building, the Rainforest Pyramid at Moody Gardens, John Sealy Hospital Towers at UTMB and Medical Arts Building (also known as Two Moody Plaza).

Climate

Galveston’s climate is classified as humid subtropical (Cfa in Köppen climate classification system), and is part of USDA Plant hardiness zone 9b. Prevailing winds from the south and southeast bring moisture from the Gulf of Mexico. Summer temperatures regularly exceed 90 °F (32 °C) and the area’s humidity drives the heat index even higher, while nighttime lows average around 80 °F (27 °C). Winters in the area are temperate with typical January highs above 60 °F (16 °C) and lows near 50 °F (10 °C). Snowfall is generally rare; however, 15.4 in (39.1 cm) of snow fell in February 1895, making the 1894–95 winter the snowiest on record. Annual rainfall averages well over 40 inches (1,000 mm) a year with some areas typically receiving over 50 inches (1,300 mm). Temperatures reaching 20 °F (−7 °C) or 100 °F (38 °C) are quite rare, having last occurred on December 23, 1989, and June 25, 2012, respectively. Record temperatures range from 8 °F (−13 °C) on February 12, 1899, up to 104 °F (40 °C) on September 5, 2000; the record cold maximum is 25 °F (−4 °C) on February 7, 1895, and again on the date of the all-time low, while, conversely, the record warm minimum is 87 °F (31 °C) set on August 31 – September 3, 2020. On average, the warmest night is at 84 °F (29 °C), seldom straying far from averages.

Hurricanes are an ever-present threat during the summer and fall season, which puts Galveston in Coastal Windstorm Area. Galveston Island and the Bolivar Peninsula are generally at the greatest risk among the communities near the Galveston Bay. However, though the island and peninsula provide some shielding, the bay shoreline still faces significant danger from storm surge. Talks of building a coastal storm barrier with a mix of federal and state funding to protect Galveston and Houston have been ongoing for years.

Notes:

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said thread from 1991 to 2020, i.e. the COOP station from January 1981 to December 1996, and Scholes Int’l from January 1997 to December 2010.

- ^ Official records for Galveston were kept at an unknown location from April 1871 to August 1946, at the COOP station from September 1946 to December 1996, and at Scholes Int’l since January 1997. The temperature record dates back to June 1874. Therefore, precipitation day normals are not currently available at Scholes Int’l. For more information, see ThreadEx Archived May 19, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

See also

Map of Texas State and its subdivision:- Anderson

- Andrews

- Angelina

- Aransas

- Archer

- Armstrong

- Atascosa

- Austin

- Bailey

- Bandera

- Bastrop

- Baylor

- Bee

- Bell

- Bexar

- Blanco

- Borden

- Bosque

- Bowie

- Brazoria

- Brazos

- Brewster

- Briscoe

- Brooks

- Brown

- Burleson

- Burnet

- Caldwell

- Calhoun

- Callahan

- Cameron

- Camp

- Carson

- Cass

- Castro

- Chambers

- Cherokee

- Childress

- Clay

- Cochran

- Coke

- Coleman

- Collin

- Collingsworth

- Colorado

- Comal

- Comanche

- Concho

- Cooke

- Coryell

- Cottle

- Crane

- Crockett

- Crosby

- Culberson

- Dallam

- Dallas

- Dawson

- Deaf Smith

- Delta

- Denton

- Dewitt

- Dickens

- Dimmit

- Donley

- Duval

- Eastland

- Ector

- Edwards

- El Paso

- Ellis

- Erath

- Falls

- Fannin

- Fayette

- Fisher

- Floyd

- Foard

- Fort Bend

- Franklin

- Freestone

- Frio

- Gaines

- Galveston

- Garza

- Gillespie

- Glasscock

- Goliad

- Gonzales

- Gray

- Grayson

- Gregg

- Grimes

- Guadalupe

- Hale

- Hall

- Hamilton

- Hansford

- Hardeman

- Hardin

- Harris

- Harrison

- Hartley

- Haskell

- Hays

- Hemphill

- Henderson

- Hidalgo

- Hill

- Hockley

- Hood

- Hopkins

- Houston

- Howard

- Hudspeth

- Hunt

- Hutchinson

- Irion

- Jack

- Jackson

- Jasper

- Jeff Davis

- Jefferson

- Jim Hogg

- Jim Wells

- Johnson

- Jones

- Karnes

- Kaufman

- Kendall

- Kenedy

- Kent

- Kerr

- Kimble

- King

- Kinney

- Kleberg

- Knox

- La Salle

- Lamar

- Lamb

- Lampasas

- Lavaca

- Lee

- Leon

- Liberty

- Limestone

- Lipscomb

- Live Oak

- Llano

- Loving

- Lubbock

- Lynn

- Madison

- Marion

- Martin

- Mason

- Matagorda

- Maverick

- McCulloch

- McLennan

- McMullen

- Medina

- Menard

- Midland

- Milam

- Mills

- Mitchell

- Montague

- Montgomery

- Moore

- Morris

- Motley

- Nacogdoches

- Navarro

- Newton

- Nolan

- Nueces

- Ochiltree

- Oldham

- Orange

- Palo Pinto

- Panola

- Parker

- Parmer

- Pecos

- Polk

- Potter

- Presidio

- Rains

- Randall

- Reagan

- Real

- Red River

- Reeves

- Refugio

- Roberts

- Robertson

- Rockwall

- Runnels

- Rusk

- Sabine

- San Augustine

- San Jacinto

- San Patricio

- San Saba

- Schleicher

- Scurry

- Shackelford

- Shelby

- Sherman

- Smith

- Somervell

- Starr

- Stephens

- Sterling

- Stonewall

- Sutton

- Swisher

- Tarrant

- Taylor

- Terrell

- Terry

- Throckmorton

- Titus

- Tom Green

- Travis

- Trinity

- Tyler

- Upshur

- Upton

- Uvalde

- Val Verde

- Van Zandt

- Victoria

- Walker

- Waller

- Ward

- Washington

- Webb

- Wharton

- Wheeler

- Wichita

- Wilbarger

- Willacy

- Williamson

- Wilson

- Winkler

- Wise

- Wood

- Yoakum

- Young

- Zapata

- Zavala

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming