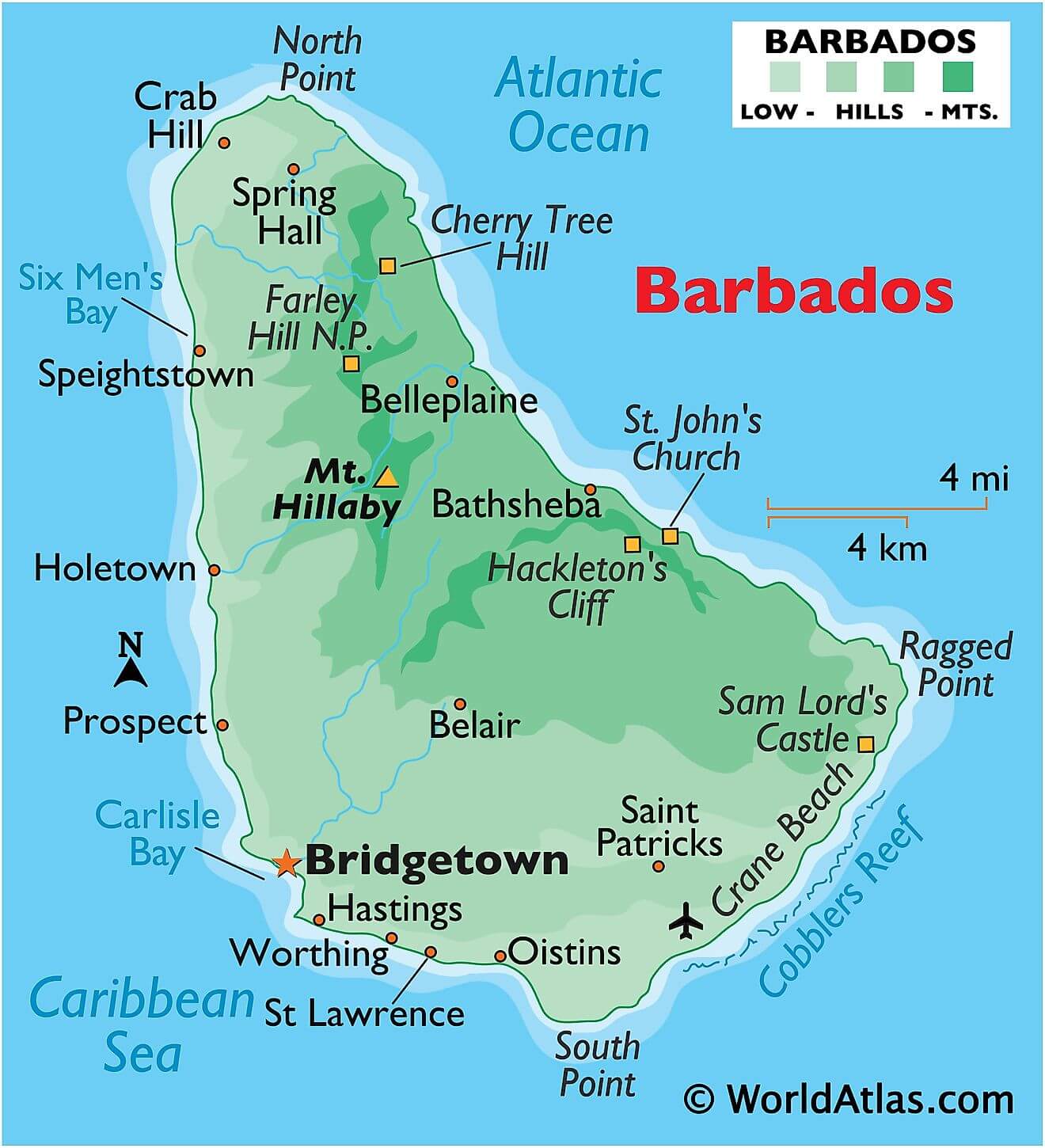

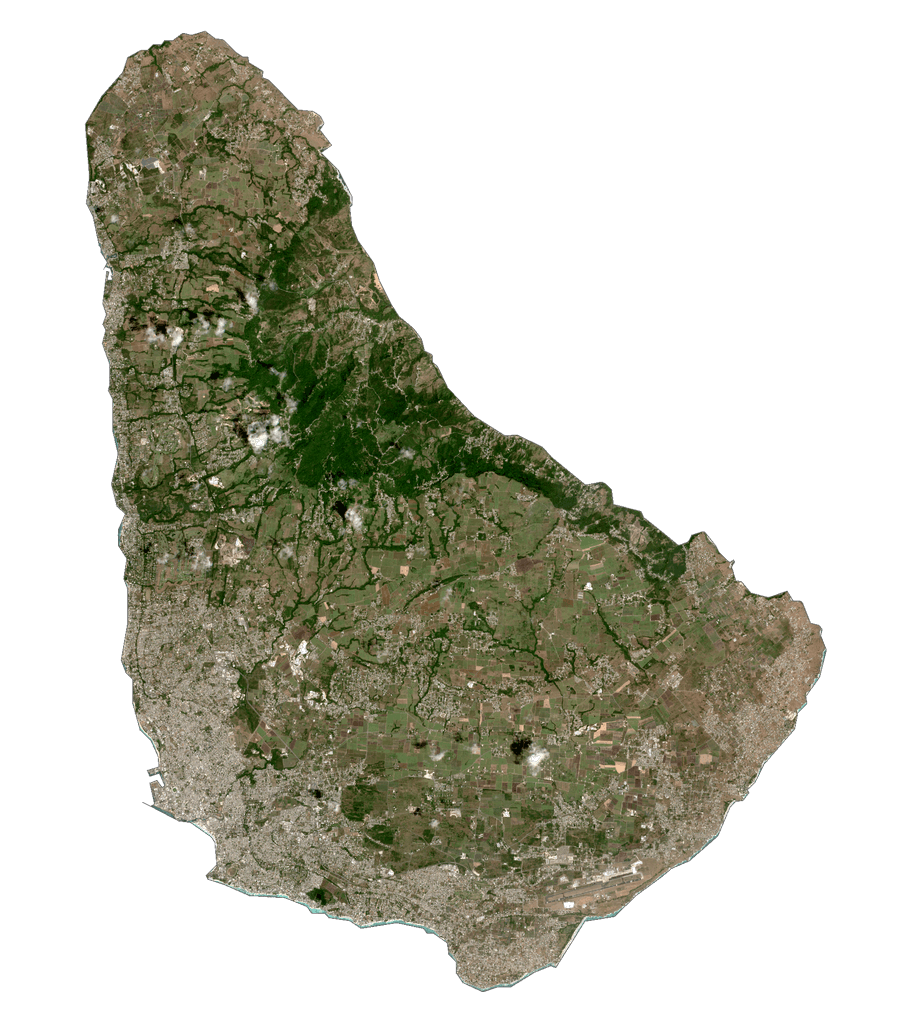

Barbados, the easternmost island in the Caribbean Sea, is relatively flat and less mountainous, in comparison to its more-mountainous island neighbours to the west. It has an area of 439 sq. km (169 sq mi).

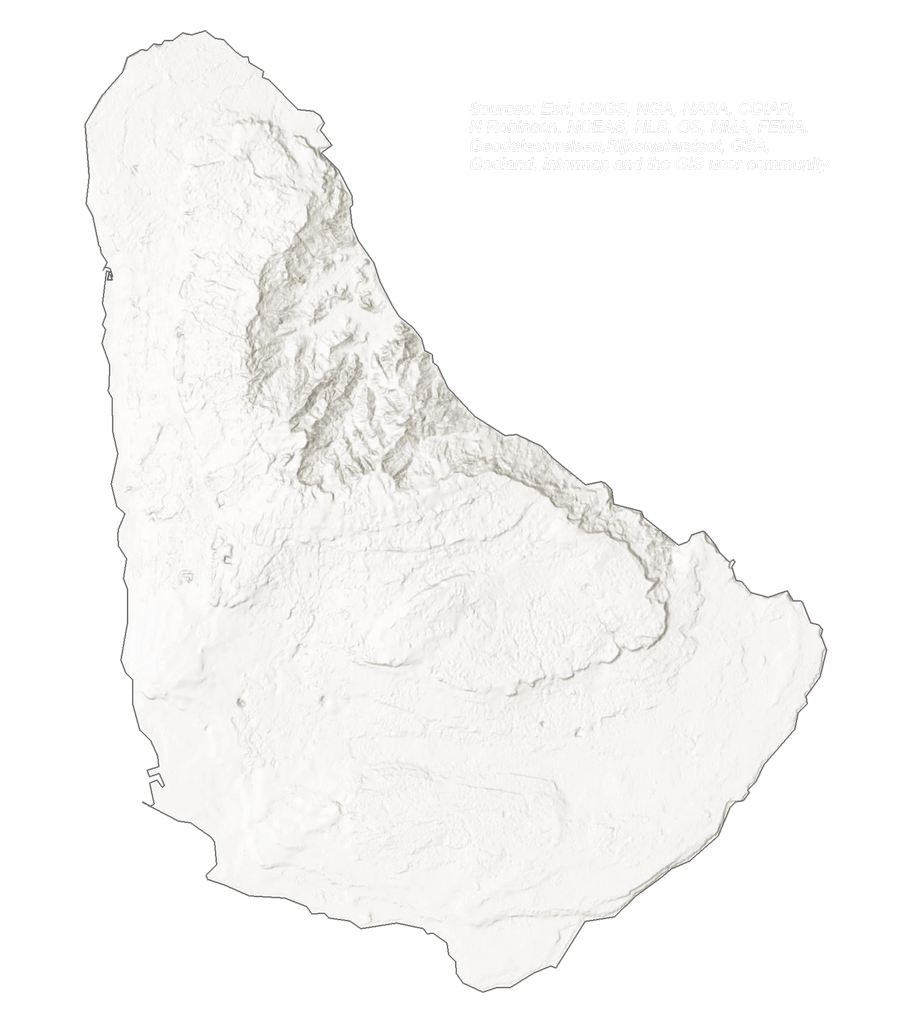

As observed on the physical map of Barbados above, the island is roughly triangular in shape. In the western half, the land rises gently from coastal lowlands into the rolling hills.

Beyond those hills in the central highland region stands the island’s highest point – Mount Hillaby, at an elevation on 1,120ft (340m) above sea level (as marked on the map by a yellow upright triangle).

In the eastern third of Barbados, the landscape rises sharply into low hills that shadow the coastline. In the southern part of the island, the highlands decline steeply to the St. George’s Valley, where the land rises to form Christ Church Ridge between the sea and the valley. Barbados is drained by a few small rivers and all rise in the hilly areas of the central and north. Rainfall also irrigates Barbados through a series of small streams. Offshore, much of the country is circled by coral reefs.

Explore Barbados with this Map

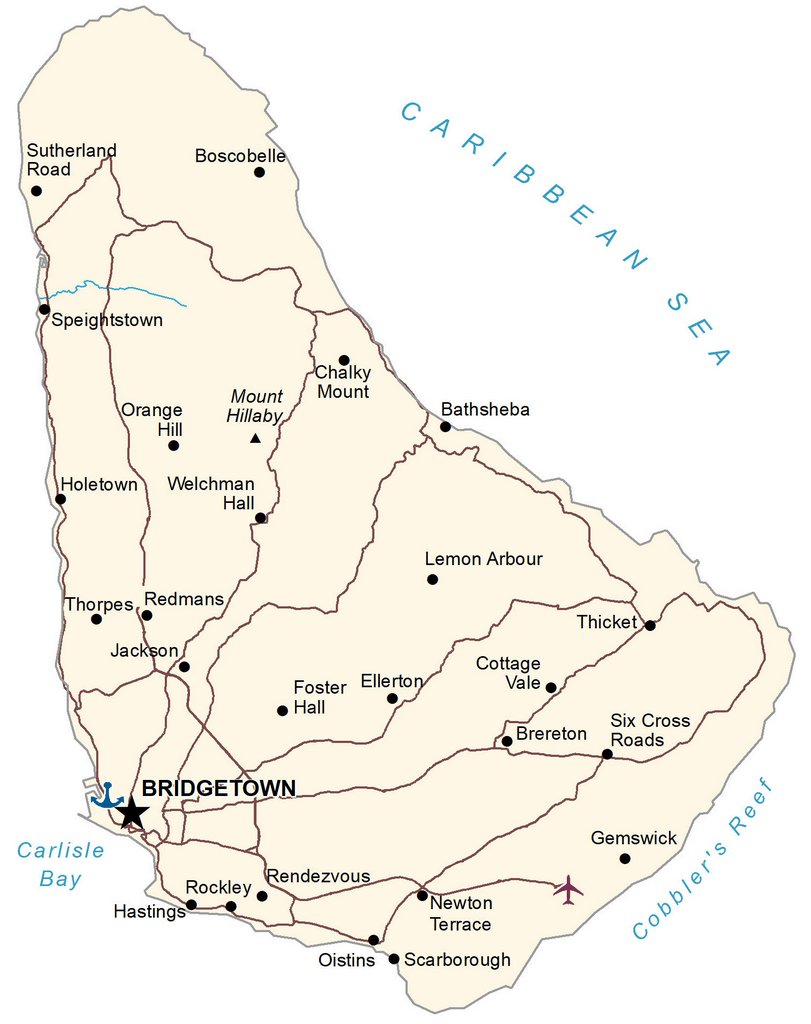

Discover the beauty of Barbados with this detailed map. With its hilly interior and coastal beaches, Barbados is the most easterly of the Caribbean islands in the Lesser Antilles chain. This map shows its major cities, towns and highways, as well as an elevation and satellite map.

Online Interactive Political Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

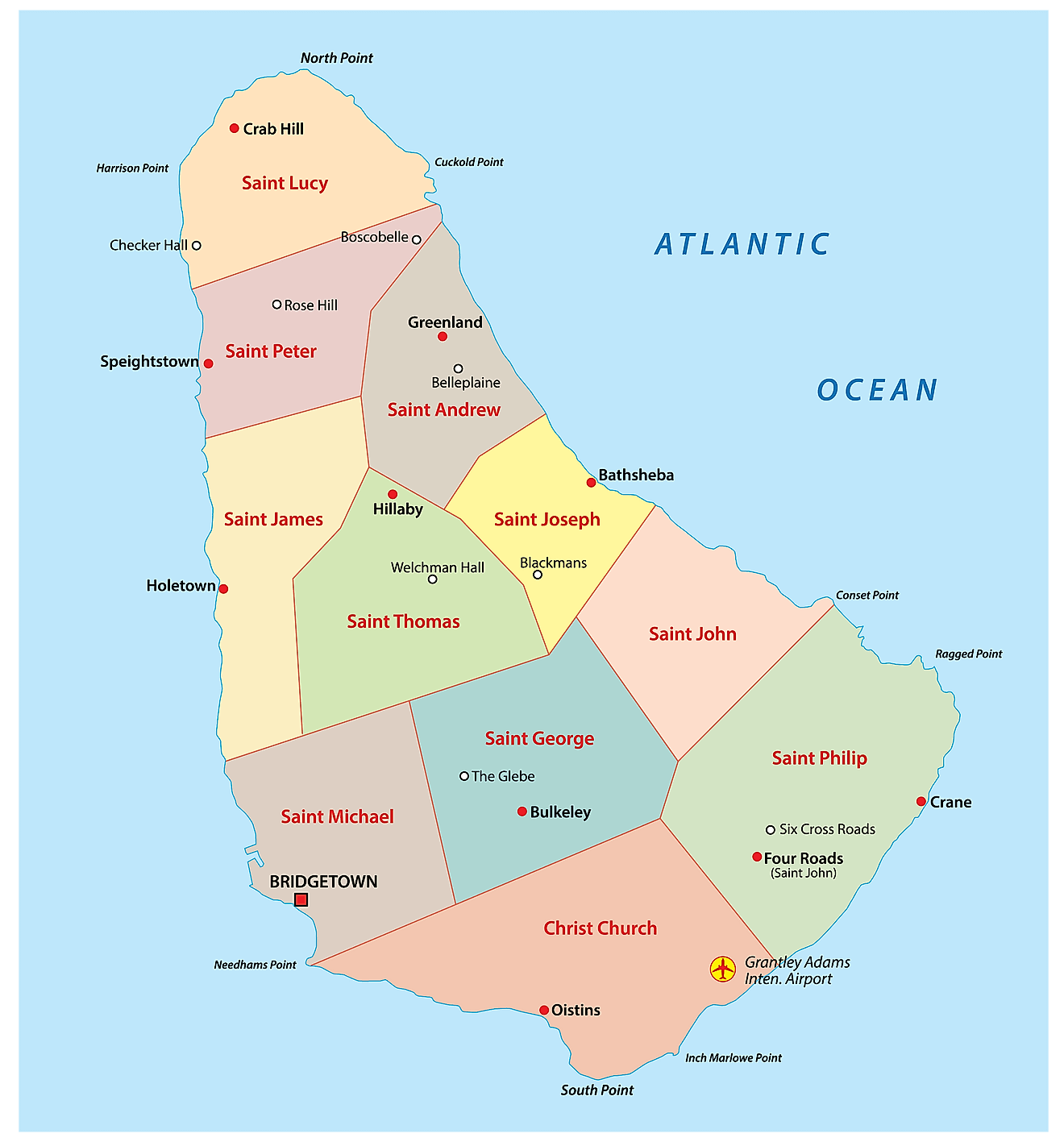

Barbados is divided into 11 parishes and 1 city. In alphabetical order, the parishes are: Christ Church, Saint Andrew, Saint George, Saint James, Saint John, Saint Joseph, Saint Lucy, Saint Michael, Saint Peter, Saint Philip, and Saint Thomas. Bridgetown is a city in Barbados.

Located in the south western part of the island country, along the Carlisle Bay is, Bridgetown – the capital and the largest city of Barbados. It is the chief administrative and financial center of the country. Bridgetown is an important sea port in the Caribbean region.

Location Maps

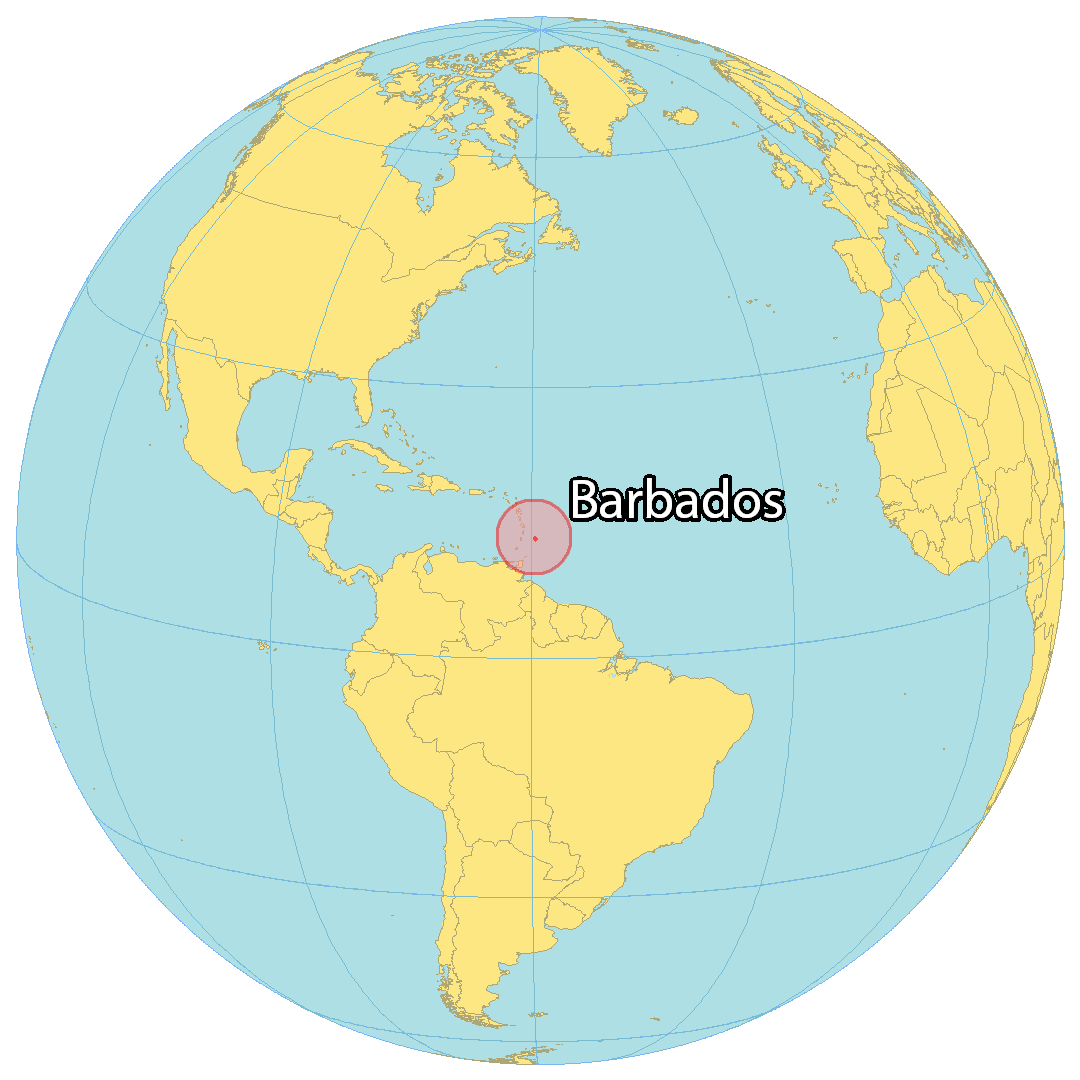

Where is Barbados?

Barbados is a single island nestled in the Caribbean Sea. It is located close to St. Vincent and the Grenadines, as well as Saint Lucia. Covering an area of 439 square kilometers (169 sq mi), it has a coastline of 97 kilometers around the island (32 x 23 km), which can be driven around in less than an hour. It is fortunate to not have any volcanoes due to its position relative to tectonic plates, and it is further away from the hurricane belt, making it less prone to storms and violent winds. The capital city of Barbados is Bridgetown, situated in the southwest corner of the island.

High Definition Political Map of Barbados

History

Geological history

Barbados is an island of volcanic origin. The volcano that created the island was formed when a disturbance in the transition zone led magma from the zone toward Earth’s surface about 30 million years ago.

About 700 thousand years ago the island emerged from the ocean as a result of a muddy sediment known as a diapir, located under Barbados, pushing it upwards. A process that is still happening, and makes the island rise about 30 centimeters on average every thousand years. Currently, dozens of inland sea reefs still dominate coastal features within terraces and cliffs of the island.

Pre-colonial period

Archeological evidence suggests humans may have first settled or visited the island circa 1600 BC. More permanent Amerindian settlement of Barbados dates to about the 4th to 7th centuries AD, by a group known as the Saladoid-Barrancoid. Settlements of Arawaks from South America appeared by around 800 AD and again in the 12th-13th century. The Kalinago (called “Caribs” by the Spanish) visited the island regularly, although there is no evidence of permanent settlement.

European arrival

It is uncertain which European nation arrived first in Barbados, which probably would have been at some point in the 15th century or 16th century. One lesser-known source points to earlier revealed works antedating contemporary sources, indicating it could have been the Spanish. Many, if not most, believe the Portuguese, en route to Brazil, were the first Europeans to come upon the island. The island was largely ignored by Europeans, though Spanish slave raiding is thought to have reduced the native population, with many fleeing to other islands.

English settlement in the 17th century

The first English ship, which had arrived on 14 May 1625, was captained by John Powell. The first settlement began on 17 February 1627, near what is now Holetown (formerly Jamestown, after King James I of England), by a group led by John Powell’s younger brother, Henry, consisting of 80 settlers and 10 English indentured labourers. Some sources state that some Africans were amongst these first settlers.

The settlement was established as a proprietary colony and funded by Sir William Courten, a City of London merchant who acquired the title to Barbados and several other islands. The first colonists were actually tenants, and much of the profits of their labour returned to Courten and his company. Courten’s title was later transferred to James Hay, 1st Earl of Carlisle, in what was called the “Great Barbados Robbery”. Carlisle then chose as governor Henry Powell, who established the House of Assembly in 1639, in an effort to appease the planters, who might otherwise have opposed his controversial appointment.

In the period 1640–1660, the West Indies attracted over two-thirds of the total number of English emigrants to the Americas. By 1650, there were 44,000 settlers in the West Indies, as compared to 12,000 on the Chesapeake and 23,000 in New England. Most English arrivals were indentured. After five years of labour, they were given “freedom dues” of about £10, usually in goods. Before the mid-1630s, they also received 5 to 10 acres (2 to 4 hectares) of land, but after that time the island filled and there was no more free land. During the Cromwellian era (1650s) this included a large number of prisoners-of-war, vagrants and people who were illicitly kidnapped, who were forcibly transported to the island and sold as servants. These last two groups were predominantly Irish, as several thousand were infamously rounded up by English merchants and sold into servitude in Barbados and other Caribbean islands during this period, a practice that came to be known as being Barbadosed. Cultivation of tobacco, cotton, ginger and indigo was thus handled primarily by European indentured labour until the start of the sugar cane industry in the 1640s and the growing reliance on and importation of African slaves.

Parish registers from the 1650s show that, for the white population, there were four times as many deaths as marriages. The mainstay of the infant colony’s economy was the growth export of tobacco, but tobacco prices eventually fell in the 1630s as Chesapeake production expanded.

Around the same time, fighting during the War of the Three Kingdoms and the Interregnum spilled over into Barbados and Barbadian territorial waters. The island was not involved in the war until after the execution of Charles I, when the island’s government fell under the control of Royalists (ironically the Governor, Philip Bell, remaining loyal to Parliament while the Barbadian House of Assembly, under the influence of Humphrey Walrond, supported Charles II). To try to bring the recalcitrant colony to heel, the Commonwealth Parliament passed an act on 3 October 1650 prohibiting trade between England and Barbados, and because the island also traded with the Netherlands, further Navigation Acts were passed, prohibiting any but English vessels trading with Dutch colonies. These acts were a precursor to the First Anglo-Dutch War. The Commonwealth of England sent an invasion force under the command of Sir George Ayscue, which arrived in October 1651. Ayscue, with a smaller force that included Scottish prisoners, surprised a larger force of Royalists, but had to resort to spying and diplomacy ultimately. On 11 January 1652, the Royalists in the House of Assembly led by Lord Willoughby surrendered, which marked the end of royalist privateering as a major threat. The conditions of the surrender were incorporated into the Charter of Barbados (Treaty of Oistins), which was signed at the Mermaid’s Inn, Oistins, on 17 January 1652.

Irish people in Barbados

Starting with Cromwell, a large percentage of the white labourer population were indentured servants and involuntarily transported people from Ireland. Irish servants in Barbados were often treated poorly, and Barbadian planters gained a reputation for cruelty. The decreased appeal of an indenture on Barbados, combined with enormous demand for labour caused by sugar cultivation, led to the use of involuntary transportation to Barbados as a punishment for crimes, or for political prisoners, and also to the kidnapping of labourers who were sent to Barbados involuntarily. Irish indentured servants were a significant portion of the population throughout the period when white servants were used for plantation labour in Barbados, and while a “steady stream” of Irish servants entered the Barbados throughout the seventeenth century, Cromwellian efforts to pacify Ireland created a “veritable tidal wave” of Irish labourers who were sent to Barbados during the 1650s. Due to inadequate historical records, the total number of Irish labourers sent to Barbados is unknown, and estimates have been “highly contentious”. While one historical source estimated that as many as 50,000 Irish people were transported to either Barbados or Virginia unwillingly during the 1650s, this estimate is “quite likely exaggerated”. Another estimate that 12,000 Irish prisoners had arrived in Barbados by 1655 has been described as “probably exaggerated” by historian Richard B. Sheridan. According to historian Thomas Bartlett, it is “generally accepted” that approximately 10,000 Irish were sent to the West Indies involuntarily, and approximately 40,000 came as voluntary indentured servants, while many also travelled as voluntary, un-indentured emigrants.

The introduction of sugar cane from Dutch Brazil in 1640 completely transformed society, the economy and the physical landscape. Barbados eventually had one of the world’s biggest sugar industries. One group instrumental in ensuring the early success of the industry was the Sephardic Jews, who had originally been expelled from the Iberian peninsula, to end up in Dutch Brazil. As the effects of the new crop increased, so did the shift in the ethnic composition of Barbados and surrounding islands. The workable sugar plantation required a large investment and a great deal of heavy labour. At first, Dutch traders supplied the equipment, financing, and African slaves, in addition to transporting most of the sugar to Europe. In 1644 the population of Barbados was estimated at 30,000, of which about 800 were of African ancestry, with the remainder mainly of English ancestry. These English smallholders were eventually bought out and the island filled up with large sugar plantations worked by African slaves. By 1660 there was near parity with 27,000 blacks and 26,000 whites. By 1666 at least 12,000 white smallholders had been bought out, died, or left the island, many choosing to emigrate to Jamaica or the American Colonies (notably the Carolinas). As a result, Barbados enacted a slave code as a way of legislatively controlling its black slave population. The law’s text was influential in laws in other colonies.

By 1680 there were 20,000 free whites and 46,000 enslaved Africans; by 1724, there were 18,000 free whites and 55,000 enslaved Africans.

18th and 19th centuries

The harsh conditions endured by the slaves resulted in several planned slave rebellions, the largest of which was Bussa’s rebellion in 1816 which was rapidly suppressed by the colonial authorities. In 1819, another slave revolt broke out on Easter Day. The revolt was put down in blood, with heads being displayed on stakes. Nevertheless, the brutality of the repression shocked even England and strengthened the abolitionist movement. Growing opposition to slavery led to its abolition in the British Empire in 1833. The plantocracy class retained control of political and economic power on the island, with most workers living in relative poverty.

The 1780 hurricane killed over 4,000 people on Barbados. In 1854, a cholera epidemic killed over 20,000 inhabitants.

20th century before independence

Deep dissatisfaction with the situation on Barbados led many to emigrate. Things came to a head in the 1930s during the Great Depression, as Barbadians began demanding better conditions for workers, the legalisation of trade unions and a widening of the franchise, which at that point was limited to male property owners. As a result of the increasing unrest the British sent a commission, called the West Indies Royal Commission, or Moyne Commission, in 1938, which recommended enacting many of the requested reforms on the islands. As a result, Afro-Barbadians began to play a much more prominent role in the colony’s politics, with universal suffrage being introduced in 1950.

Prominent among these early activists was Grantley Herbert Adams, who helped found the Barbados Labour Party (BLP) in 1938. He became the first Premier of Barbados in 1953, followed by fellow BLP-founder Hugh Gordon Cummins from 1958 to 1961. A group of left-leaning politicians who advocated swifter moves to independence broke off from the BLP and founded the Democratic Labour Party (DLP) in 1955. The DLP subsequently won the 1961 Barbadian general election and their leader Errol Barrow became premier.

Full internal self-government was enacted in 1961. Barbados joined the short-lived West Indies Federation from 1958 to 1962, later gaining full independence on 30 November 1966. Errol Barrow became the country’s first prime minister. Barbados opted to remain within the Commonwealth of Nations. The broken trident on its national flag recalls its legacy when Barbados was a British colony and symbolises that it has broken away from three centuries of colonial rule.

The effect of independence meant that the Queen of the United Kingdom ceased to have sovereignty over Barbados, but the island chose to remain a constitutional monarchy with Elizabeth II as Queen of Barbados. The Monarch was represented locally by a Governor-General.

Post-independence era

The Barrow government sought to diversify the economy away from agriculture, seeking to boost industry and the tourism sector. Barbados was also at the forefront of regional integration efforts, spearheading the creation of CARIFTA and CARICOM. The DLP lost the 1976 Barbadian general election to the BLP under Tom Adams. Adams adopted a more conservative and strongly pro-Western stance, allowing the Americans to use Barbados as the launchpad for their invasion of Grenada in 1983. Adams died in office in 1985 and was replaced by Harold Bernard St. John; however, St. John lost the 1986 Barbadian general election, which saw the return of the DLP under Errol Barrow, who had been highly critical of the US intervention in Grenada. Barrow, too, died in office, and was replaced by Lloyd Erskine Sandiford, who remained Prime Minister until 1994.

Owen Arthur of the BLP won the 1994 Barbadian general election, remaining Prime Minister until 2008. Arthur was a strong advocate of republicanism, though a planned referendum to replace Queen Elizabeth as Head of State in 2008 never took place. The DLP won the 2008 Barbadian general election, but the new Prime Minister David Thompson died in 2010 and was replaced by Freundel Stuart. The BLP returned to power in 2018 under Mia Mottley, who became Barbados’s first female Prime Minister.

The Government of Barbados announced on 15 September 2020 that it intended to become a republic by 30 November 2021, the 55th anniversary of its independence resulting in the replacement of the Barbadian monarchy with an elected president. Barbados would then cease to be a Commonwealth realm, but could maintain membership in the Commonwealth of Nations, like Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago.

On 20 September 2021, just over a full year after the announcement for the transition was made, the Constitution (Amendment) (No. 2) Bill, 2021 was introduced to the Parliament of Barbados. Passed on 6 October, the Bill made amendments to the Constitution of Barbados, introducing the office of the president of Barbados to replace the role of Elizabeth, Queen of Barbados. The following week, on 12 October 2021, incumbent Governor-General of Barbados Sandra Mason was jointly nominated by the Prime Minister and Leader of the Opposition as candidate to be the first president of Barbados, and was subsequently elected on 20 October. Mason took office on 30 November 2021. Charles III, who, as Prince Charles, was heir apparent to the Barbadian Crown at the time, attended the swearing-in ceremony in Bridgetown at the invitation of the Government of Barbados.

Queen Elizabeth sent a message of congratulations to President Mason and the people of Barbados, saying: “As you celebrate this momentous day, I send you and all Barbadians my warmest good wishes for your happiness, peace and prosperity in the future.”

A survey that was conducted between 23 October 2021, and 10 November 2021, by the University of the West Indies showed 34% of respondents being in favour of transitioning to a republic, while 30% were indifferent. Notably, no overall majority was found in the survey; with 24% not indicating a preference, and the remaining 12% being opposed to the removal of Queen Elizabeth.

On 20 June 2022, a Constitutional Review Commission was formed and sworn in by Jeffrey Gibson (who, at the time, was serving temporarily as Acting President of Barbados) to review the Constitution of Barbados.

The Commission will have an 18-month timeline to complete its work. They are expected to solicit input from members of the public in Barbados via a series of face-to-face and online events.

Physical Map of Barbados