Mozambique occupies an area of 801,590 sq. km in Southern Africa.

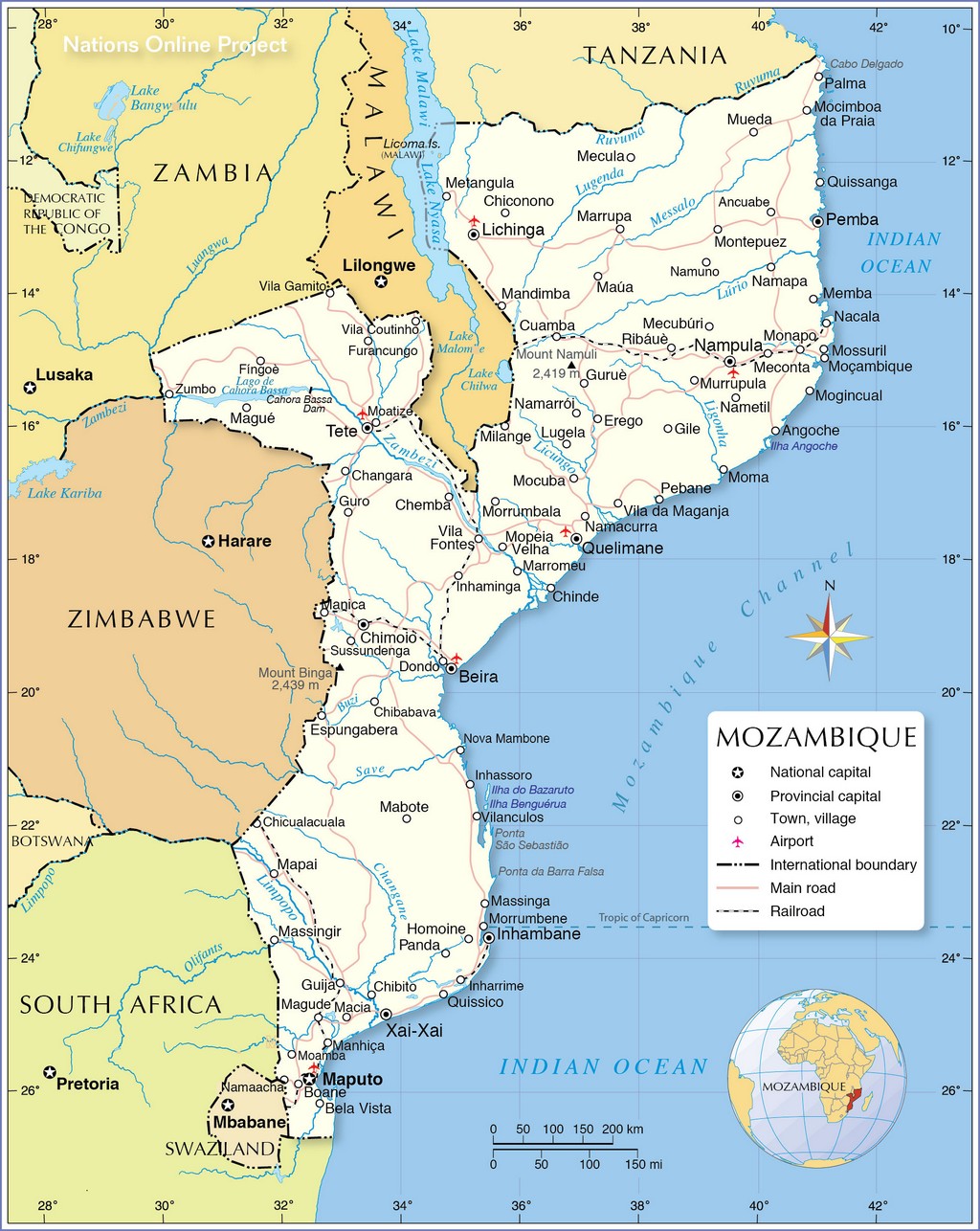

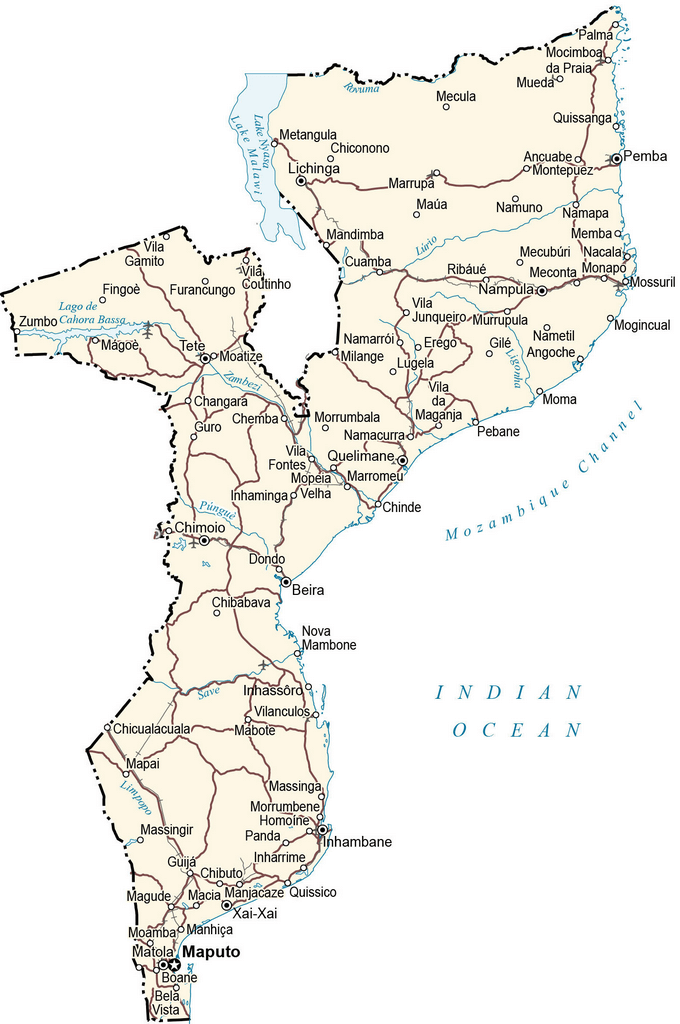

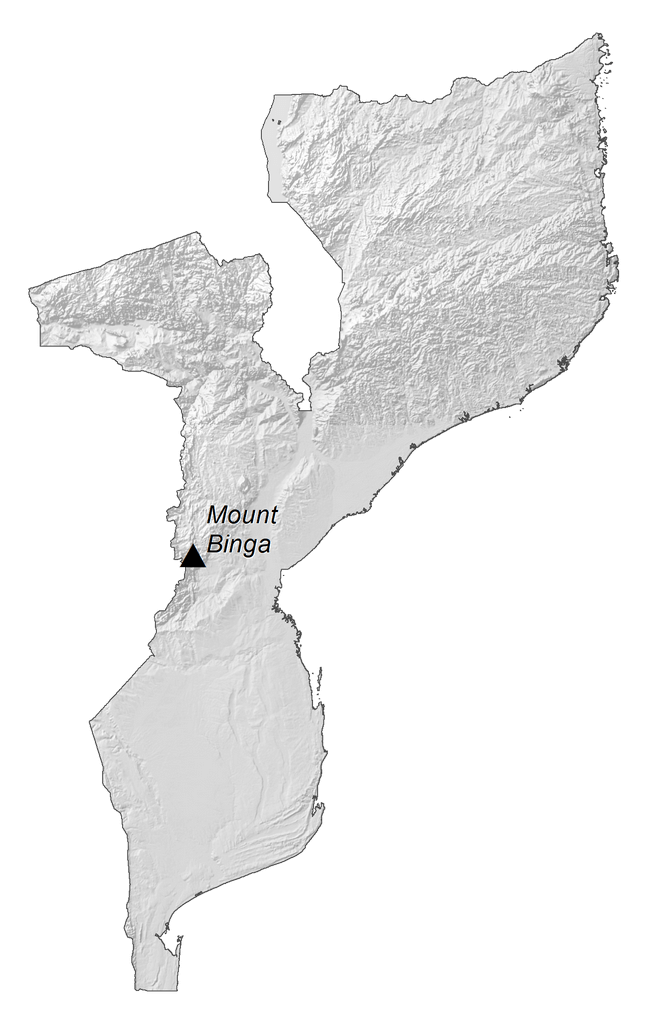

Mozambique is divided into two major topographical regions:To the north of the Zambezi river that runs almost through central Mozambique, a narrow coastline and bordering plateau slope upward into hills and a series of rugged highlands like Angonia Highlands and Lichinga Highlands (as shown on map) punctuated by scattered mountains.

South of the Zambezi River, the lowlands are much wider with scattered hills and mountains along its borders with South Africa, Swaziland and Zambia.

Monte Binga (marked on map), peaking at 2,435 m, is the highest point of Mozambique; the Indian Ocean (0 m) is the lowest.

The country is drained by several significant rivers, with the Zambezi being the largest and most important.The Zambezi is in fact the fourth-longest river in Africa, and the largest flowing into the Indian Ocean from Africa. Other important rivers flowing in Mozambique include Limpopo, Licungo, Lurio, Rovuma, and others.

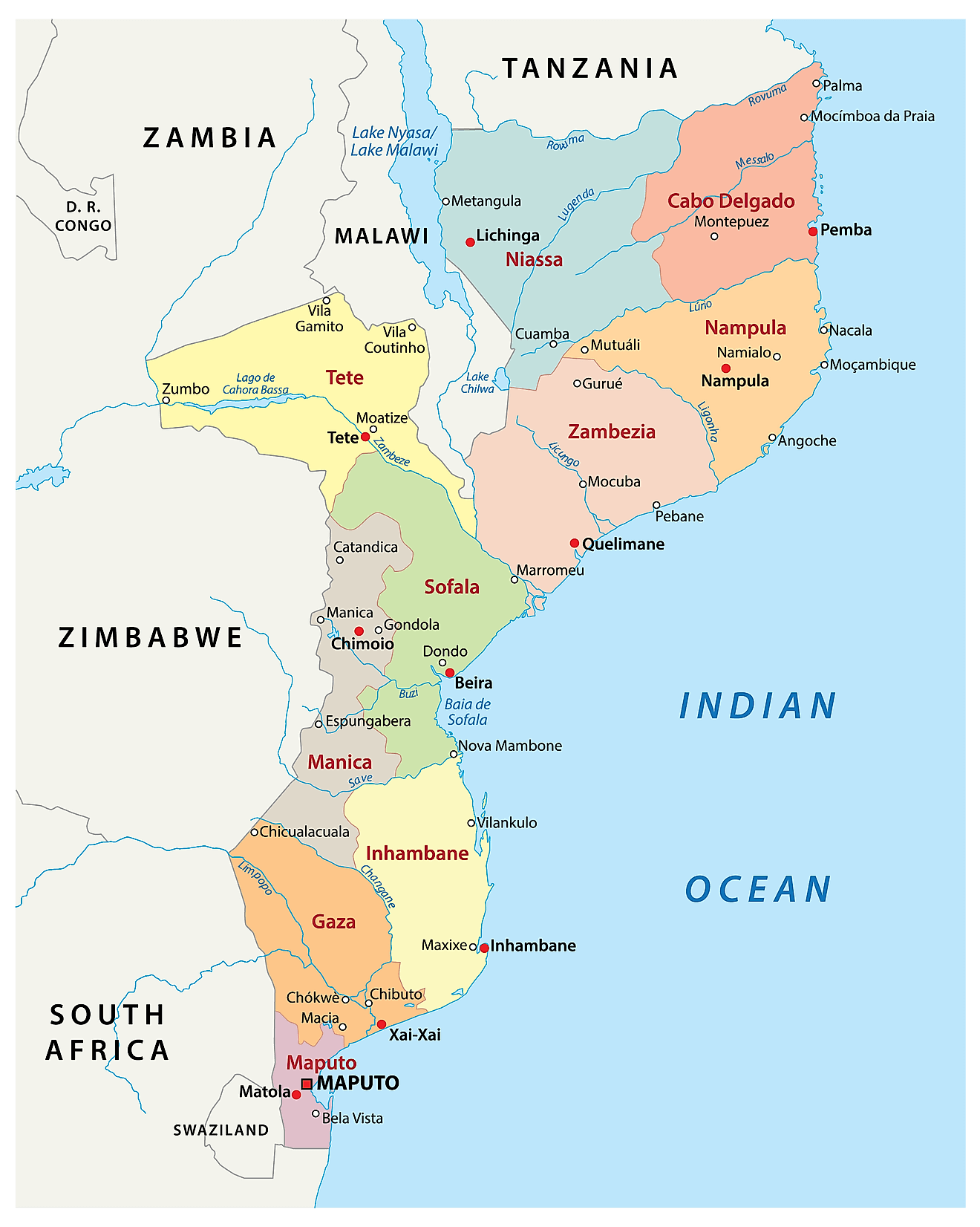

Lake Malawi (Nyasa) is the country’s major lake. As seen on the map, it is located on Mozambique’s border with Malawi. The Cahora Bassa is Africa’s fourth-largest artificial lake. A small slice of Malawi’s Lake Chiuta sits in Mozambique.

Explore the stunning natural beauty of Mozambique with this interactive map! Featuring cities, lakes, rivers, and roads, this map provides a detailed overview of the country. Get a closer look at the Zambezi River, the Mozambique Plateau, and the Angolan Highlands with the help of satellite imagery and an elevation map.

Online Interactive Political Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

Mozambique is divided into 10 provinces. In alphabetical order, these are as follows: Cabo Delgado, Gaza, Inhambane, Manica, Maputo, Nampula, Niassa, Sofala, Tete, Zambezia. The country also hosts one city, the Cidade de Maputo. The provinces are subdivided into 129 districts which, in turn, are divided into 405 Administrative Posts. The latter is divided into Localidades.

With an area of 129,056 sq. km, Niassa is the biggest province of Mozambique by area while Nampula is the most populous one.

Location Maps

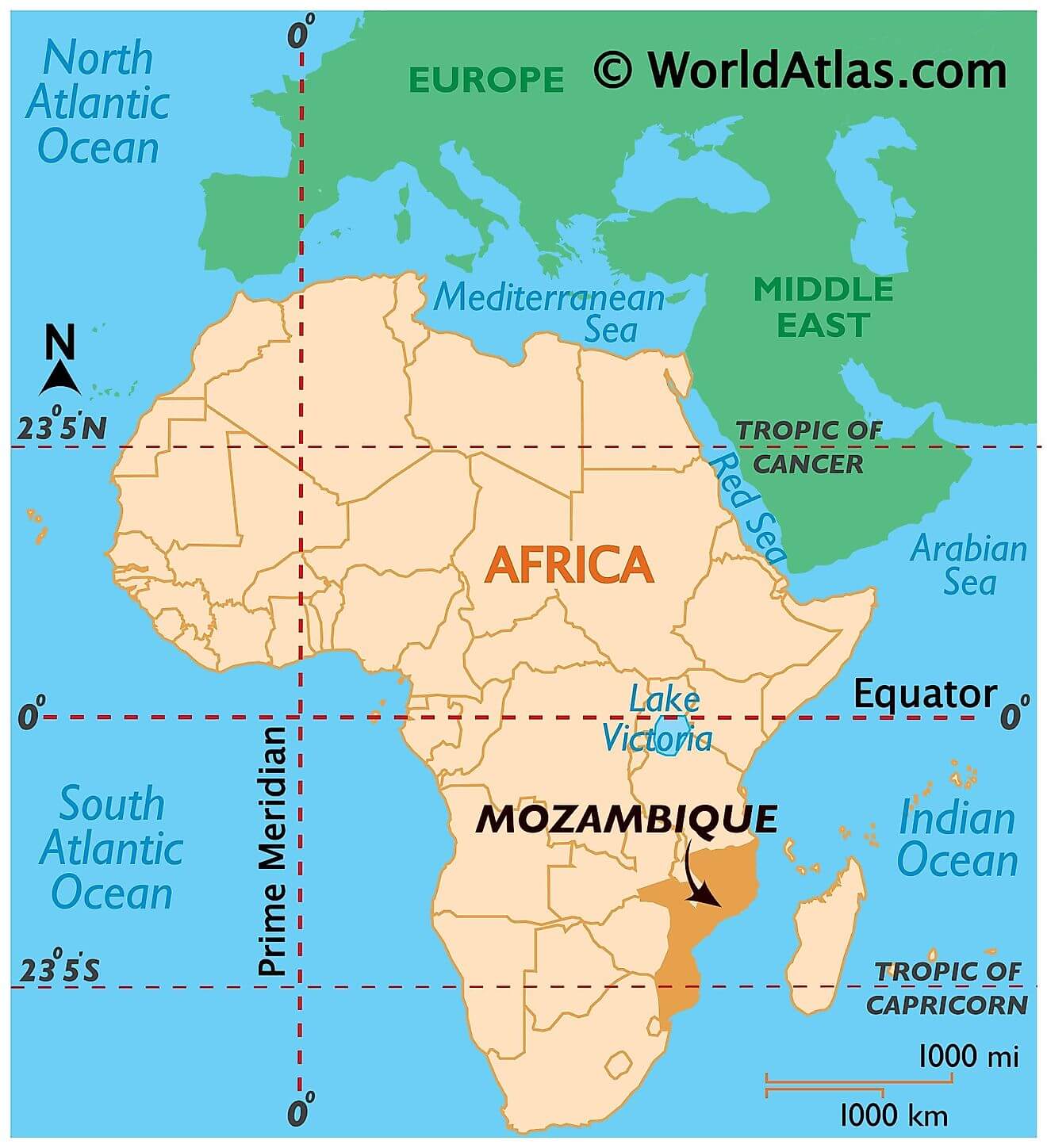

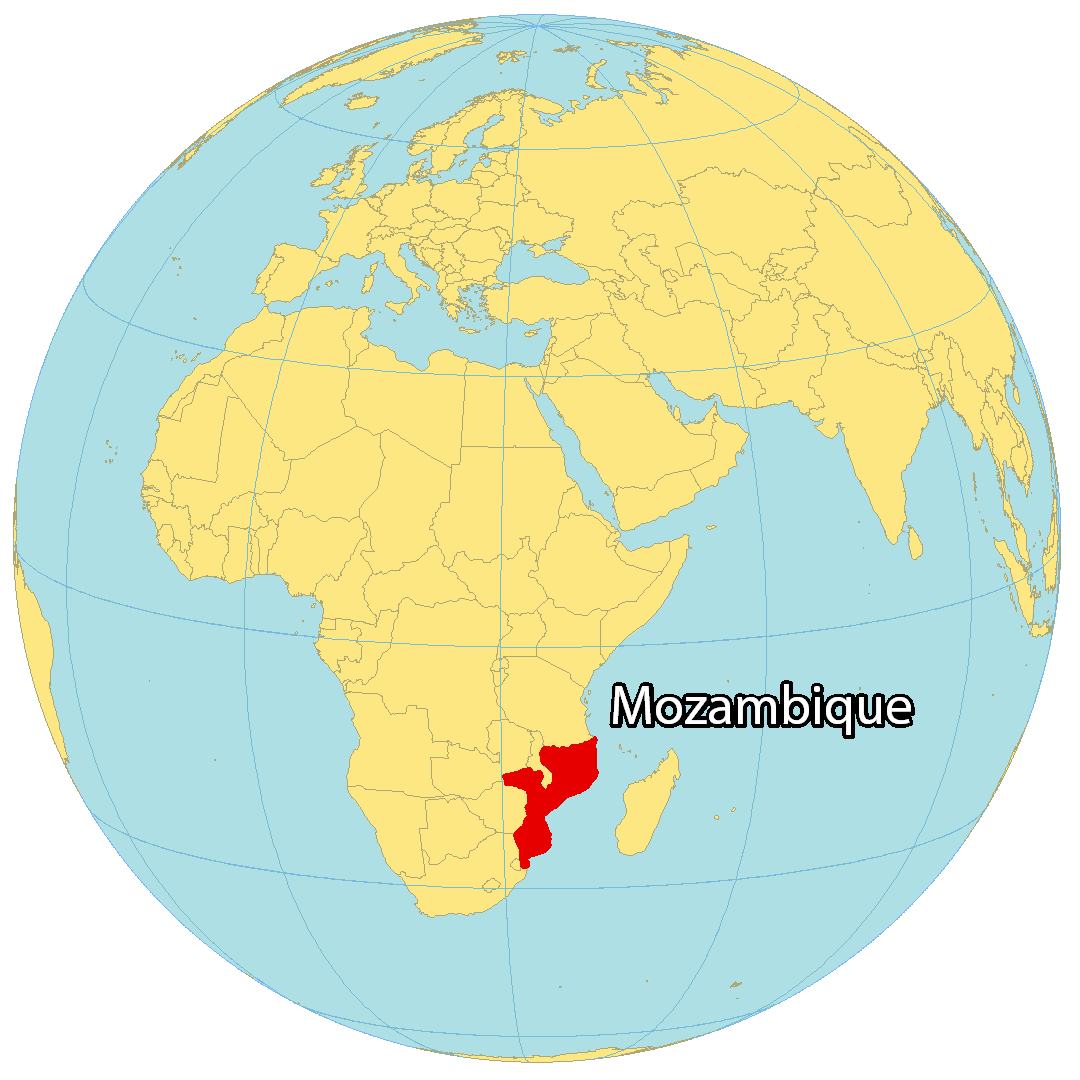

Where is Mozambique?

Mozambique is situated in southern Africa, renowned for its stunning beaches, abundant wildlife, and natural heritage. It borders six countries, including Tanzania and Malawi to the north, Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, as well as Eswatini and South Africa to the southwest. With a coastline of 2,300 kilometers (1,430 mi) along the Indian Ocean, Mozambique has the longest coastline of any African country. The Mozambique Channel separates it from Madagascar, about 425 kilometers (264 mi) away. The capital and largest city of Mozambique is Maputo (formerly Lourenço Marques).

High Definition Political Map of Mozambique

History

Bantu migrations

Bantu-speaking peoples migrated into Mozambique as early as the 4th century BC. It is believed between the 1st and 5th centuries AD, waves of migration from the west and north went through the Zambezi River valley and then gradually into the plateau and coastal areas of Southern Africa. They established agricultural communities or societies based on herding cattle. They brought with them the technology for smelting and smithing iron.

Swahili Coast

From the late first millennium AD, vast Indian Ocean trade networks extended as far south into Mozambique as evidenced by the ancient port town of Chibuene. Beginning in the 9th century, a growing involvement in Indian Ocean trade led to the development of numerous port towns along the entire East African coast, including modern day Mozambique. Largely autonomous, these towns broadly participated in the incipient Swahili culture. Islam was often adopted by urban elites, facilitating trade. In Mozambique, Sofala, Angoche, and Mozambique Island were regional powers by the 15th century.

The towns traded with merchants from both the African interior and the broader Indian Ocean world. Particularly important were the gold and ivory caravan routes. Inland states like the Kingdom of Zimbabwe and Kingdom of Mutapa provided the coveted gold and ivory, which were then exchanged up the coast to larger port cities like Kilwa and Mombasa.

Portuguese Mozambique (1498–1975)

The Island of Mozambique after which the country is named, is a small coral island at the mouth of Mossuril Bay on the Nacala coast of northern Mozambique, first explored by Europeans in the late 15th century.

When Portuguese explorers reached Mozambique in 1498, Arab-trading settlements had existed along the coast and outlying islands for several centuries. From about 1500, Portuguese trading posts and forts displaced the Arabic commercial and military hegemony, becoming regular ports of call on the new European sea route to the east, the first steps in what was to become a process of colonisation.

The voyage of Vasco da Gama around the Cape of Good Hope in 1498 marked the Portuguese entry into trade, politics, and society of the region. The Portuguese gained control of the Island of Mozambique and the port city of Sofala in the early 16th century, and by the 1530s, small groups of Portuguese traders and prospectors seeking gold penetrated the interior regions, where they set up garrisons and trading posts at Sena and Tete on the Zambezi and tried to gain exclusive control over the gold trade.

In the central part of the Mozambique territory, the Portuguese attempted to legitimise and consolidate their trade and settlement positions through the creation of prazos. These land grants tied emigrants to their settlements, and inland Mozambique was largely left to be administered by prazeiros, the grant holders, while central authorities in Portugal concentrated their direct exercise of power on, in their view, the more important Portuguese possessions in Asia and the Americas. Slavery in Mozambique pre-dated European-contact. African rulers and chiefs dealt in enslaved people, first with Arab Muslim traders, who sent the enslaved to Middle East Asia cities and plantations, and later with Portuguese and other European traders. In a continuation of the trade, slaves were supplied by warring local African rulers, who raided enemy tribes and sold their captives to the prazeiros. The authority of the prazeiros was exercised and upheld amongst the local population by armies of these enslaved men, whose members became known as Chikunda. Continuing emigration from Portugal occurred at comparatively low levels until late in the nineteenth century, promoting “Africanisation”. While prazos were originally intended to be held solely by Portuguese colonists, through intermarriage and the relative isolation of prazeiros from ongoing Portuguese influences, the prazos became African-Portuguese or African-Indian.

Although Portuguese influence gradually expanded, its power was limited and exercised through individual settlers and officials who were granted extensive autonomy. The Portuguese were able to wrest much of the coastal trade from Arab Muslims between 1500 and 1700, but, with the Arab Muslim seizure of Portugal’s key foothold at Fort Jesus on Mombasa Island (now in Kenya) in 1698, the pendulum began to swing in the other direction. As a result, investment lagged while Lisbon devoted itself to the more lucrative trade with India and the Far East and to the colonisation of Brazil.

The Mazrui and Omani Arabs reclaimed much of the Indian Ocean trade, forcing the Portuguese to retreat south. Many prazos had declined by the mid-19th century, but several of them survived. During the 19th century other European powers, particularly the British (British South Africa Company) and the French (Madagascar), became increasingly involved in the trade and politics of the region around the Portuguese East African territories.

By the early 20th century the Portuguese had shifted the administration of much of Mozambique to large private companies, like the Mozambique Company, the Zambezia Company and the Niassa Company, controlled and financed mostly by British financiers such as Solomon Joel, which established railroad lines to their neighbouring colonies (South Africa and Rhodesia). Although slavery had been legally abolished in Mozambique, at the end of the 19th century the chartered companies enacted a forced labour policy and supplied cheap—often forced—African labour to the mines and plantations of the nearby British colonies and South Africa. The Zambezia Company, the most profitable chartered company, took over several smaller prazeiro holdings and established military outposts to protect its property. The chartered companies built roads and ports to bring their goods to market including a railroad linking present-day Zimbabwe with the Mozambican port of Beira.

Due to their unsatisfactory performance and the shift, under the corporatist Estado Novo regime of Oliveira Salazar, toward a stronger Portuguese control of Portuguese Empire’s economy, the companies’ concessions were not renewed when they ran out. This was what happened in 1942 with the Mozambique Company, which, however, continued to operate in the agricultural and commercial sectors as a corporation, and had already happened in 1929 with the termination of the Niassa Company’s concession. In 1951, the Portuguese overseas colonies in Africa were rebranded as Overseas Provinces of Portugal.

The Mueda massacre of 16 June 1960, resulted in the death of Makonde protestors, which provoked the struggle of independence from Portuguese rule of Mozambique.

Mozambican War of Independence (1964–1975)

As communist and anti-colonial ideologies spread out across Africa, many clandestine political movements were established in support of Mozambican independence. These movements claimed that since policies and development plans were primarily designed by the ruling authorities for the benefit of Mozambique’s Portuguese population, little attention was paid to Mozambique’s tribal integration and the development of its native communities.

According to the official guerrilla statements, this affected a majority of the indigenous population who suffered both state-sponsored discrimination and enormous social pressure. Many felt they had received too little opportunity or resources to upgrade their skills and improve their economic and social situation to a degree comparable to that of the Europeans. Statistically, Mozambique’s Portuguese whites were indeed wealthier and more skilled than the black indigenous majority. As a response to the guerrilla movement, the Portuguese government from the 1960s and principally the early 1970s initiated gradual changes with new socioeconomic developments and egalitarian policies.

The Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (FRELIMO) initiated a guerrilla campaign against Portuguese rule in September 1964. This conflict—along with the two others already initiated in the other Portuguese colonies of Angola and Portuguese Guinea—became part of the so-called Portuguese Colonial War (1961–1974). From a military standpoint, the Portuguese regular army maintained control of the population centres while the guerrilla forces sought to undermine their influence in rural and tribal areas in the north and west. As part of their response to FRELIMO, the Portuguese government began to pay more attention to creating favourable conditions for social development and economic growth.

Independence (1975)

FRELIMO took control of the territory after ten years of sporadic warfare, as well as Portugal’s own return to democracy after the fall of the authoritarian Estado Novo regime in the Carnation Revolution of April 1974 and the failed coup of 25 November 1975. Within a year, most of the 250,000 Portuguese in Mozambique had left—some expelled by the government of the nearly independent territory, some left the country to avoid possible reprisals from the unstable government—and Mozambique became independent from Portugal on 25 June 1975. A law had been passed on the initiative of the relatively unknown Armando Guebuza of the FRELIMO party, ordering the Portuguese to leave the country in 24 hours with only 20 kilograms (44 pounds) of luggage. Unable to salvage any of their assets, most of them returned to Portugal penniless.

Mozambican Civil War (1977–1992)

The new government under President Samora Machel established a one-party state based on Marxist principles. It received diplomatic and some military support from Cuba and the Soviet Union and proceeded to crack down on opposition. Starting shortly after independence, the country was plagued from 1977 to 1992 by a long and violent civil war between the opposition forces of anti-communist Mozambican National Resistance (RENAMO) rebel militias and the FRELIMO regime. This conflict characterised the first decades of Mozambican independence, combined with sabotage from the neighbouring states of Rhodesia and South Africa, ineffective policies, failed central planning, and the resulting economic collapse. This period was also marked by the exodus of Portuguese nationals and Mozambicans of Portuguese heritage, a collapsed infrastructure, lack of investment in productive assets, and government nationalisation of privately owned industries, as well as widespread famine.

During most of the civil war, the FRELIMO-formed central government was unable to exercise effective control outside of urban areas, many of which were cut off from the capital. RENAMO-controlled areas included up to 50% of the rural areas in several provinces, and it is reported that health services of any kind were isolated from assistance for years in those areas. The problem worsened when the government cut back spending on health care. The war was marked by mass human rights violations from both sides of the conflict, with both RENAMO and FRELIMO contributing to the chaos through the use of terror and indiscriminate targeting of civilians. The central government executed tens of thousands of people while trying to extend its control throughout the country and sent many people to “re-education camps” where thousands died.

During the war, RENAMO proposed a peace agreement based on the secession of RENAMO-controlled northern and western territories as the independent Republic of Rombesia, but FRELIMO refused, insisting on the undivided sovereignty of the entire country. An estimated one million Mozambicans perished during the civil war, 1.7 million took refuge in neighbouring states, and several million more were internally displaced. The FRELIMO regime also gave shelter and support to South African (African National Congress) and Zimbabwean (Zimbabwe African National Union) rebel movements, while the governments of Rhodesia and later Apartheid South Africa backed RENAMO in the civil war. Between 300,000 and 600,000 people died of famine during the war.

On 19 October 1986, Machel was on his way back from an international meeting in Zambia in the presidential Tupolev Tu-134 aircraft when the plane crashed in the Lebombo Mountains near Mbuzini in the Mpumalanga region of apartheid-ruling South Africa. There were ten survivors, but President Machel and thirty-three others died, including ministers and officials of the Mozambique government. The United Nations’ Soviet delegation issued a minority report contending that their expertise and experience had been undermined by the South Africans. Representatives of the Soviet Union advanced the theory that the plane had been intentionally diverted by a false navigational beacon signal, using a technology provided by military intelligence operatives of the South African government.

Machel’s successor Joaquim Chissano implemented sweeping changes in the country, starting reforms such as changing from Marxism to capitalism and began peace talks with RENAMO. The new constitution enacted in 1990 provided for a multi-party political system, market-based economy, and free elections. The civil war ended in October 1992 with the Rome General Peace Accords, first brokered by the Christian Council of Mozambique (Council of Protestant Churches) and then taken over by Community of Sant’Egidio. Peace returned to Mozambique, under the supervision of the peacekeeping force of the United Nations.

Democratic era (1993–present)

Mozambique held elections in 1994, which were accepted by most political parties as free and fair although still contested by many nationals and observers alike. FRELIMO won, under Joaquim Chissano, while RENAMO, led by Afonso Dhlakama, ran as the official opposition. In 1995, Mozambique joined the Commonwealth of Nations, becoming, at the time, the only member nation that had never been part of the British Empire.

By mid-1995, over 1.7 million refugees who had sought asylum in neighbouring countries had returned to Mozambique, part of the largest repatriation witnessed in sub-Saharan Africa. An additional four million internally displaced persons had returned to their homes. In December 1999, Mozambique held elections for a second time since the civil war, which were again won by FRELIMO. RENAMO accused FRELIMO of fraud and threatened to return to civil war but backed down after taking the matter to the Supreme Court and losing.

In early 2000, a cyclone caused widespread flooding, killing hundreds and devastating the already precarious infrastructure. There were widespread suspicions that foreign aid resources had been diverted by powerful leaders of FRELIMO. Carlos Cardoso, a journalist investigating these allegations, was murdered, and his death was never satisfactorily explained.

Indicating in 2001 that he would not run for a third term, Chissano criticised leaders who stayed on longer than he had, which was generally seen as a reference to Zambian President Frederick Chiluba, who at the time was considering a third term, and Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe, then in his fourth term. Presidential and National Assembly elections took place on 1–2 December 2004. FRELIMO candidate Armando Guebuza won with 64% of the popular vote, and Dhlakama received 32% of the popular vote. FRELIMO won 160 seats in Parliament, with a coalition of RENAMO and several small parties winning the 90 remaining seats. Guebuza was inaugurated as the President of Mozambique on 2 February 2005 and served two five-year terms. His successor, Filipe Nyusi, became the fourth President of Mozambique on 15 January 2015.

From 2013 to 2019, a low-intensity insurgency by RENAMO occurred, mainly in the country’s central and northern regions. On 5 September 2014, Guebuza and Dhlakama signed the Accord on Cessation of Hostilities, which brought the military hostilities to a halt and allowed both parties to concentrate on the general elections to be held in October 2014. However, after the general elections, a new political crisis emerged. RENAMO did not recognise the validity of the election results and demanded the control of six provinces – Nampula, Niassa, Tete, Zambezia, Sofala, and Manica – where they claimed to have won a majority. About 12,000 refugees fled to Malawi. The UNHCR, Doctors Without Borders, and Human Rights Watch reported that government forces had torched villages and carried out summary executions and sexual abuses.

In October 2019, President Filipe Nyusi was re-elected after a landslide victory in general election. FRELIMO won 184 seats, RENAMO got 60 seats and the MDM party received the remaining 6 seats in the National Assembly. Opposition did not accept the results because of allegations of fraud and irregularities. FRELIMO secured two-thirds majority in parliament which allowed FRELIMO to re-adjust the constitution without needing the agreement of the opposition.

Since 2017, the country has faced an ongoing insurgency by Islamist groups. In September 2020, ISIL insurgents captured and briefly occupied Vamizi Island in the Indian Ocean. In March 2021, dozens of civilians were killed and 35,000 others were displaced after Islamist rebels seized the city of Palma. In December 2021, nearly 4,000 Mozambicans fled their villages after an intensification of jihadist attacks in Niassa.

Physical Map of Mozambique

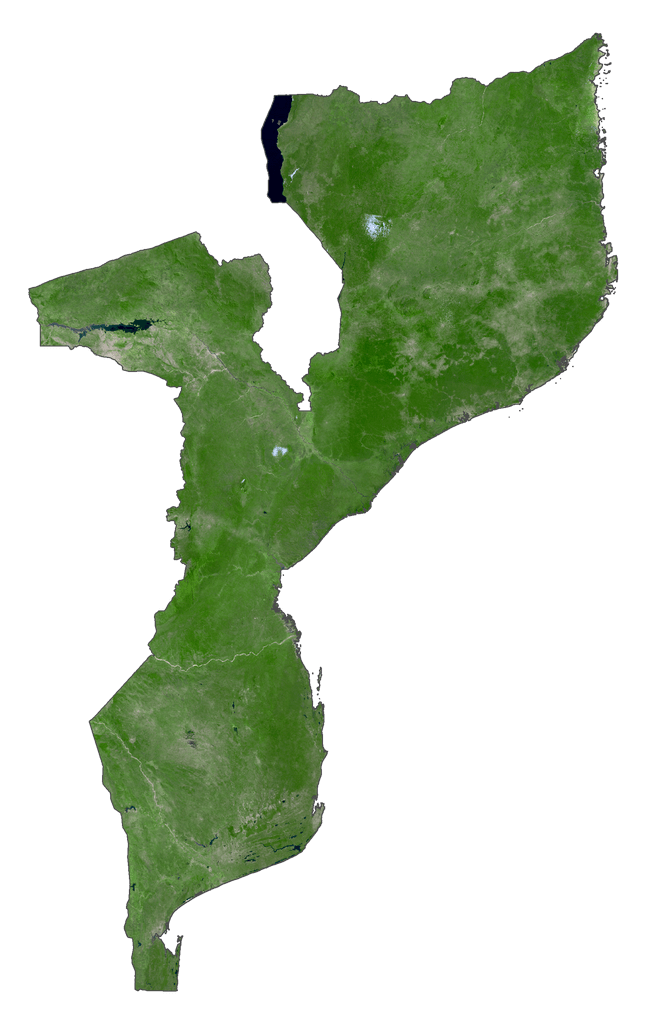

Mozambique Satellite Map

Topo Map