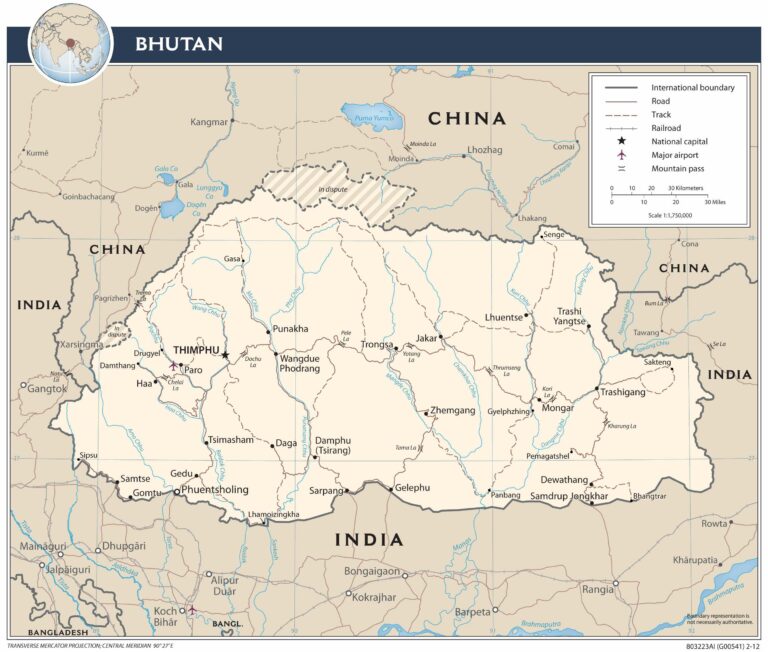

The Kingdom of Bhutan covers an area of 38,394 sq. km at the eastern limits of the Himalayas. The length of the country is only slightly larger than the width giving it a compact shape.

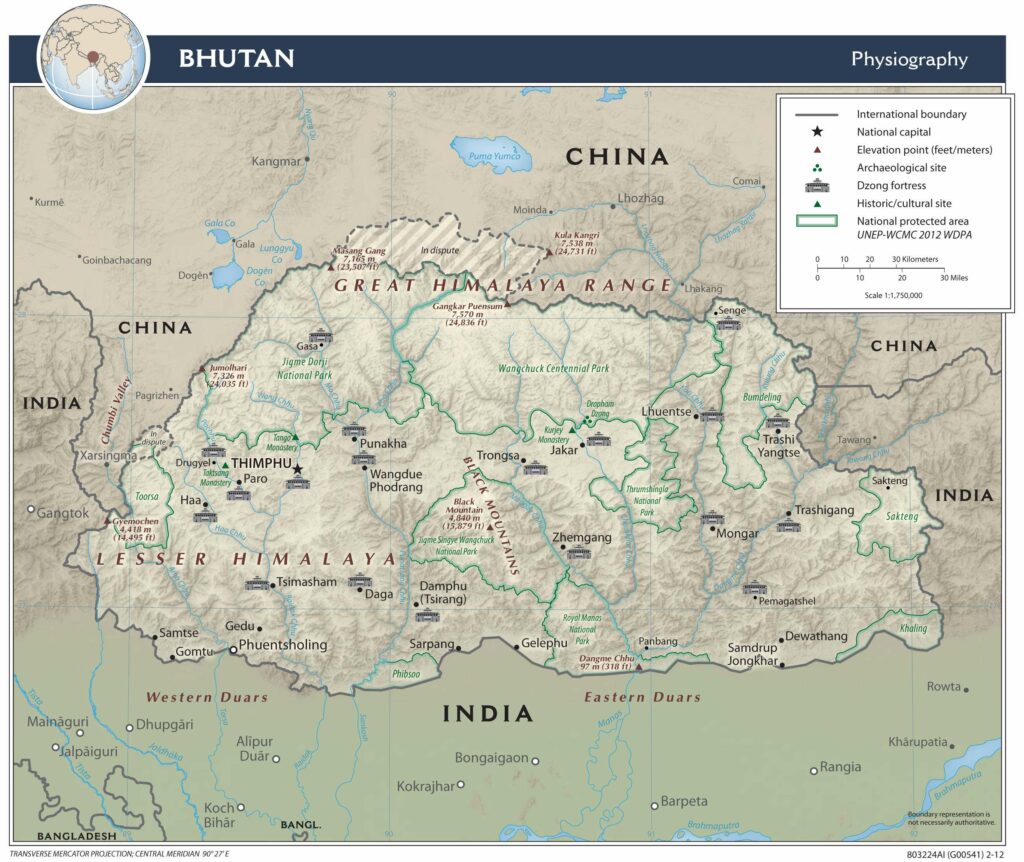

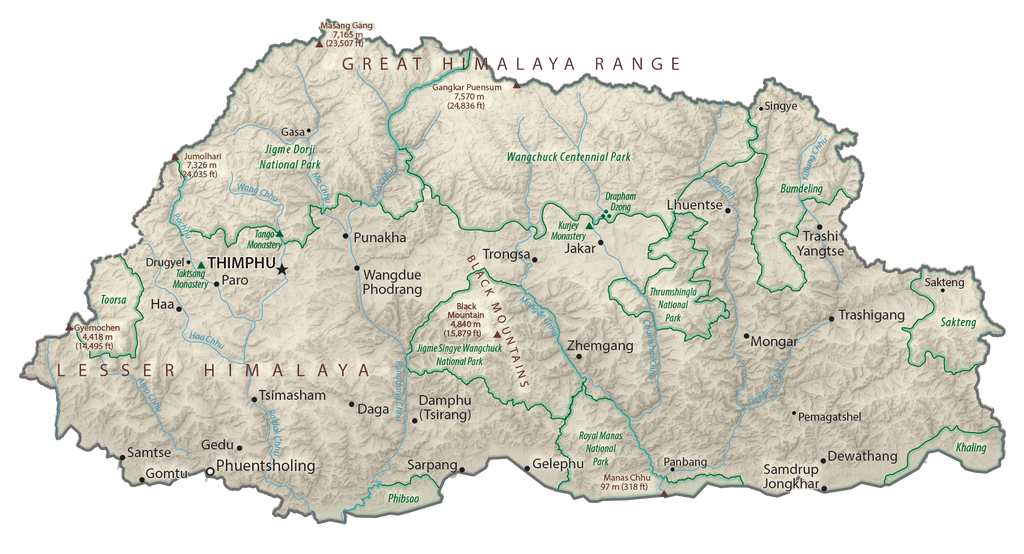

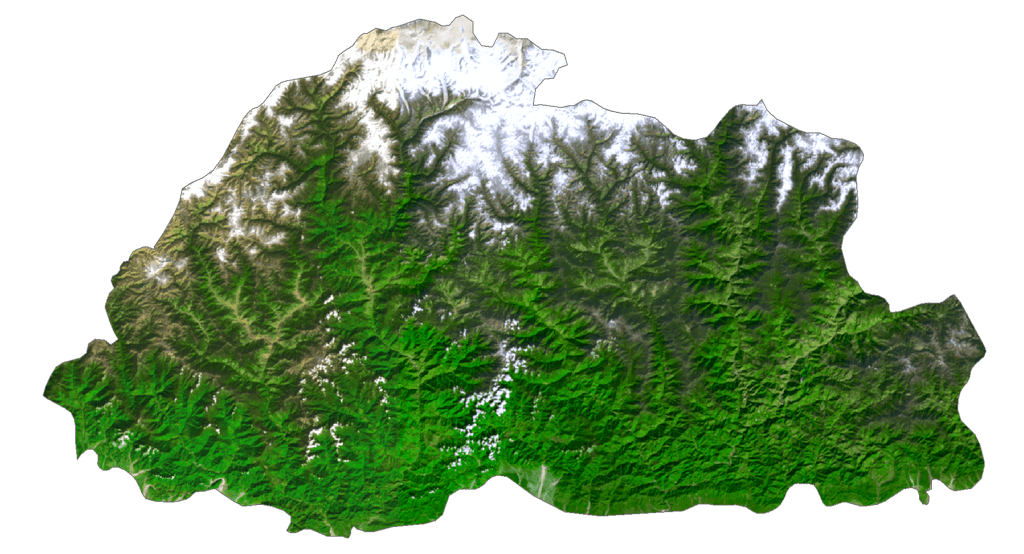

As observed on the physical map of Bhutan above, the country is highly mountainous. Here several peaks of the Himalayas reach as high 7,000 m along the country’s northern border with China. The tallest point in the country (as marked on the map by a yellow upright triangle) is the Kula Kangri. However, there is a lot of dispute regarding the location of this peak as some authorities claim it is part of Tibet. Instead, the 7,570 metres (24,840 ft) tall Gangkhar Puensum is often regarded as Bhutan’s tallest peak. The latter is the world’s tallest unclimbed mountain.

The central parts of Bhutan feature the mountains of the lesser or the lower Himalayas.

Along its southern border with India, the Himalayan foothills and associated lowland areas are found. Large parts here are forested.

The lowest point in Bhutan at 97 m (318 ft) above sea level is located in the Drangme Chhu river system.

The lowest point is located in the Drangme Chhu, a river system in central and eastern Bhutan, at 97 m (318 ft) above sea level.

Numerous small rivers drain the land, including the Dangme, Mangde, Sankosh and Torsa.

Explore the beauty of Bhutan with this interactive map! It showcases satellite imagery, elevation, and reference information, as well as major cities, towns, roads, rivers, administrative districts, and topographic features such as the Great Himalayas Range. Zoom in and out to get a better view of the area, or use the reference information to find out more about the geography of Bhutan.

Online Interactive Political Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

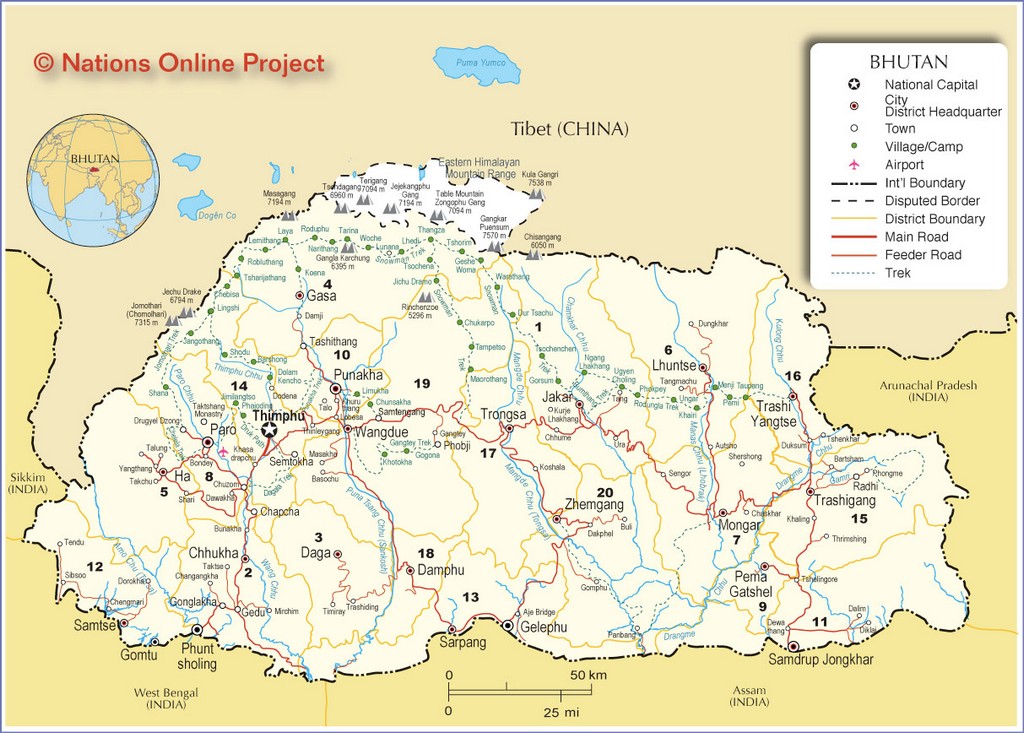

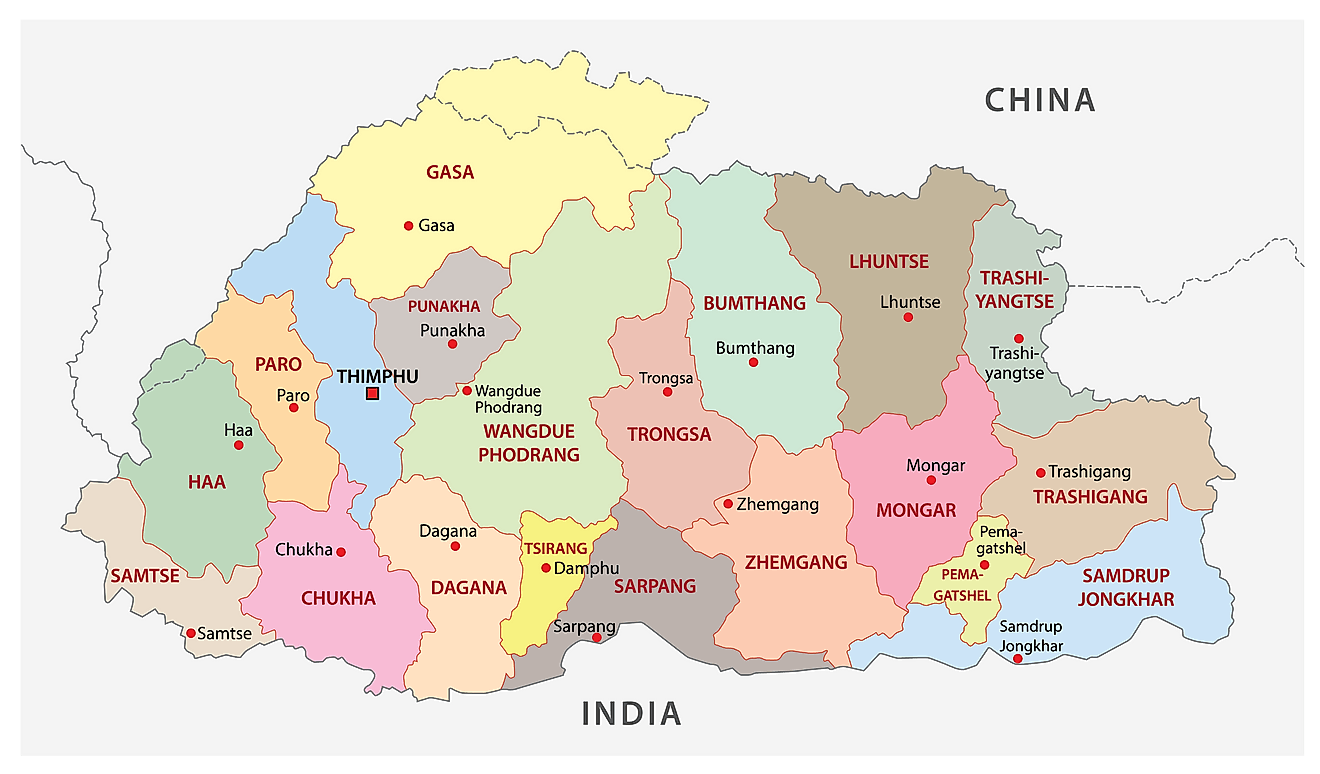

Bhutan (officially, The Kingdom of Bhutan) is divided into 20 districts (dzongkhags). In alphabetical order, these districts are: Bumthang, Chhukha, Dagana, Gasa, Haa, Lhuentse, Mongar, Paro, Pemagatshel, Punakha, Samdrup Jongkhar, Samtse, Sarpang, Thimphu, Trashigang, Trashi Yangtse, Trongsa, Tsirang, Wangdue Phodrang and Zhemgang.

With a population of around 754,388, Bhutan is the second-least populated nation in South Asia. Located in the west-central part of the country, surrounding the Thimphu River Valley is Thimphu city – the capital and the largest city of Bhutan. Situated at an altitude of 2,320m, Thimphu is the 5th highest capital in the world. Thimphu also serves as the administrative and economic center of Bhutan. Phuntsholing – located in the southern part of the country, near the India-Bhutan border, serves as the financial center of Bhutan.

Location Maps

Where is Bhutan?

Bhutan is a landlocked country located in Southern Asia on the eastern edge of the Himalayas. It borders two countries with China to the north and India to the south. Although Nepal and Bangladesh are close to Bhutan, they don’t have a shared border. The origin of the name “Bhutan” is “Land of the Thunder Dragon”, which is derived from the thunderous storms that occur in Bhutan due to the Great Himalayas Range. Despite being known for measuring national happiness, Bhutan still ranks relatively low due to its poverty.

High Definition Political Map of Bhutan

Bhutan Administrative Map

Physical Map of Bhutan

Geography

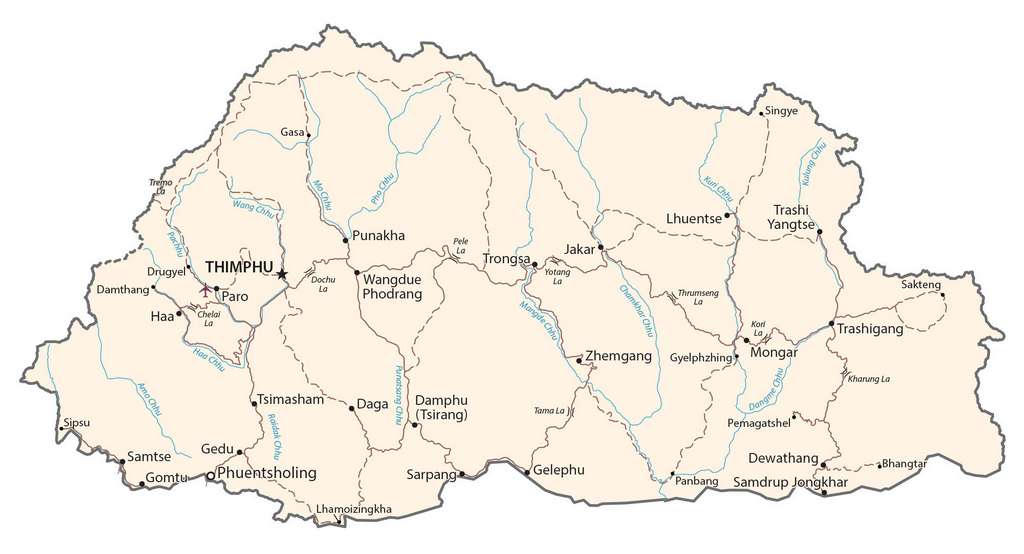

Bhutan is on the southern slopes of the eastern Himalayas, landlocked between the Tibet Autonomous Region of China to the north and the Indian states of Sikkim, West Bengal, Assam to the west and south, and the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh to the east. It lies between latitudes 26°N and 29°N, and longitudes 88°E and 93°E. The land consists mostly of steep and high mountains crisscrossed by a network of swift rivers that form deep valleys before draining into the Indian plains. Elevation rises from 200 m (660 ft) in the southern foothills to more than 7,000 m (23,000 ft). This great geographical diversity combined with equally diverse climate conditions contributes to Bhutan’s outstanding range of biodiversity and ecosystems.

Bhutan’s northern region consists of an arc of Eastern Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows reaching up to glaciated mountain peaks with an extremely cold climate at the highest elevations. Most peaks in the north are over 7,000 m (23,000 ft) above sea level; the highest point is 7,570-metre (24,840 ft)-tall Gangkhar Puensum, which has the distinction of being the highest unclimbed mountain in the world. The lowest point, at 98 m (322 ft), is in the valley of Drangme Chhu, where the river crosses the border with India. Watered by snow-fed rivers, alpine valleys in this region provide pasture for livestock, tended by a sparse population of migratory shepherds.

The Black Mountains in Bhutan’s central region form a watershed between two major river systems: the Mo Chhu and the Drangme Chhu. Peaks in the Black Mountains range between 1,500 and 4,925 m (4,921 and 16,158 ft) above sea level, and fast-flowing rivers have carved out deep gorges in the lower mountain areas. The forests of the central Bhutan mountains consist of Eastern Himalayan subalpine conifer forests in higher elevations and Eastern Himalayan broadleaf forests in lower elevations. The Woodlands of the central region provide most of Bhutan’s forest production. The Torsa, Raidak, Sankosh, and Manas are Bhutan’s main rivers, flowing through this region. Most of the population lives in the central highlands.

In the south, the Shiwalik Hills are covered with dense Himalayan subtropical broadleaf forests, alluvial lowland river valleys, and mountains up to around 1,500 m (4,900 ft) above sea level. The foothills descend into the subtropical Duars Plain, which is the eponymous gateway to strategic mountain passes (also known as dwars or dooars; literally, “doors” in Assamese, Bengali, Maithili, Bhojpuri, and Magahi languages). Most of the Duars is in India, but a 10 to 15 km (6.2 to 9.3 mi)-wide strip extends into Bhutan. The Bhutan Duars is divided into two parts, the northern and southern Duars.

The northern Duars, which abut the Himalayan foothills, have rugged, sloping terrain and dry, porous soil with dense vegetation and abundant wildlife. The southern Duars have moderately fertile soil, heavy savanna grass, dense, mixed jungle, and freshwater springs. Mountain rivers, fed by melting snow or monsoon rains, empty into the Brahmaputra River in India. Data released by the Ministry of Agriculture showed that the country had a forest cover of 64% as of October 2005.

- Landscape of Bhutan

Gangkar Puensum, the highest mountain in Bhutan

Sub-alpine Himalayan landscape

A Himalayan peak from Bumthang

Jigme Dorji National Park

The Haa Valley in Western Bhutan

Climate

Bhutan’s climate varies with elevation, from subtropical in the south to temperate in the highlands and polar-type climate with year-round snow in the north. Bhutan experiences five distinct seasons: summer, monsoon, autumn, winter and spring. Western Bhutan has the heavier monsoon rains; southern Bhutan has hot humid summers and cool winters; central and eastern Bhutan are temperate and drier than the west with warm summers and cool winters.

Biodiversity

Bhutan signed the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity on 11 June 1992, and became a party to the convention on 25 August 1995. It has subsequently produced a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, with two revisions, the most recent of which was received by the convention on 4 February 2010.

Bhutan has a rich primate life, with rare species such as the golden langur. A variant Assamese macaque has also been recorded, which is regarded by some authorities as a new species, Macaca munzala.

The Bengal tiger, clouded leopard, hispid hare and the sloth bear live in the tropical lowland and hardwood forests in the south. In the temperate zone, grey langur, tiger, goral and serow are found in mixed conifer, broadleaf and pine forests. Fruit-bearing trees and bamboo provide habitat for the Himalayan black bear, red panda, squirrel, sambar, wild pig and barking deer. The alpine habitats of the great Himalayan range in the north are home to the snow leopard, blue sheep, Himalayan marmot, Tibetan wolf, antelope, Himalayan musk deer and the takin, Bhutan’s national animal. The endangered wild water buffalo occurs in southern Bhutan, although in small numbers.

More than 770 species of bird have been recorded in Bhutan. The globally endangered white-winged duck has been added recently in 2006 to Bhutan’s bird list.

More than 5,400 species of plants are found in Bhutan, including Pedicularis cacuminidenta. Fungi form a key part of Bhutanese ecosystems, with mycorrhizal species providing forest trees with mineral nutrients necessary for growth, and with wood decay and litter decomposing species playing an important role in natural recycling.

The Eastern Himalayas has been identified as a global biodiversity hotspot and counted among the 234 globally outstanding ecoregions of the world in a comprehensive analysis of global biodiversity undertaken by WWF between 1995 and 1997.

According to the Swiss-based International Union for Conservation of Nature, Bhutan is viewed as a model for proactive conservation initiatives. The Kingdom has received international acclaim for its commitment to the maintenance of its biodiversity. This is reflected in the decision to maintain at least sixty percent of the land area under forest cover, to designate more than 40% of its territory as national parks, reserves and other protected areas, and most recently to identify a further nine percent of land area as biodiversity corridors linking the protected areas. All of Bhutan’s protected land is connected to one another through a vast network of biological corridors, allowing animals to migrate freely throughout the country. Environmental conservation has been placed at the core of the nation’s development strategy, the middle path. It is not treated as a sector but rather as a set of concerns that must be mainstreamed in Bhutan’s overall approach to development planning and to be buttressed by the force of law. The country’s constitution mentions environmental standards in multiple sections.

Although Bhutan’s natural heritage is still largely intact, the government has said that it cannot be taken for granted and that conservation of the natural environment must be considered one of the challenges that will need to be addressed in the years ahead. Nearly 56.3% of all Bhutanese are involved with agriculture, forestry or conservation. The government aims to promote conservation as part of its plan to target Gross National Happiness. It currently has net negative greenhouse gas emissions because the small amount of pollution it creates is absorbed by the forests that cover most of the country. While the entire country collectively produces 2,200,000 metric tons (2,200,000 long tons; 2,400,000 short tons) of carbon dioxide a year, the immense forest covering 72% of the country acts as a carbon sink, absorbing more than four million tons of carbon dioxide every year. Bhutan had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 8.85/10, ranking it 16th globally out of 172 countries.

Bhutan has a number of progressive environmental policies that have caused the head of the UNFCCC to call it an “inspiration and role model for the world on how economies and different countries can address climate change while at the same time improving the life of the citizen.” For example, electric cars have been pushed in the country and as of 2014 make up a tenth of all cars. Because the country gets most of its energy from hydroelectric power, it does not emit significant greenhouse gases for energy production.

In practice, the overlap of these extensive protected lands with populated areas has led to mutual habitat encroachment. Protected wildlife has entered agricultural areas, trampling crops and killing livestock. In response, Bhutan has implemented an insurance scheme, begun constructing solar powered alarm fences, watch towers, and search lights, and has provided fodder and salt licks outside human settlement areas to encourage animals to stay away.

The huge market value of the Ophiocordyceps sinensis fungus crop collected from the wild has also resulted in unsustainable exploitation which is proving very difficult to regulate.

Bhutan has enforced a plastic ban rule from 1 April 2019, where plastic bags were replaced by alternative bags made of jute and other biodegradable material.