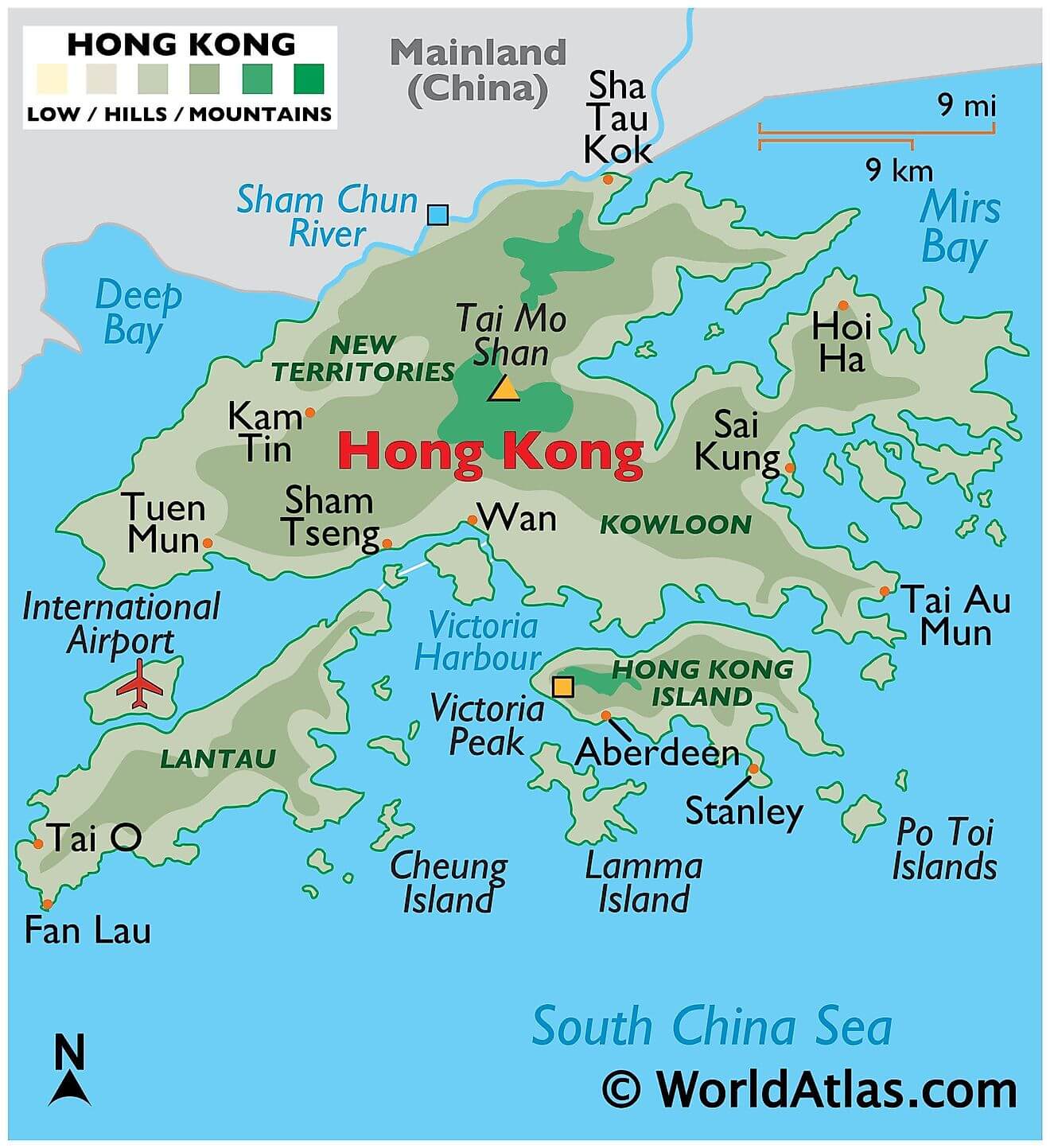

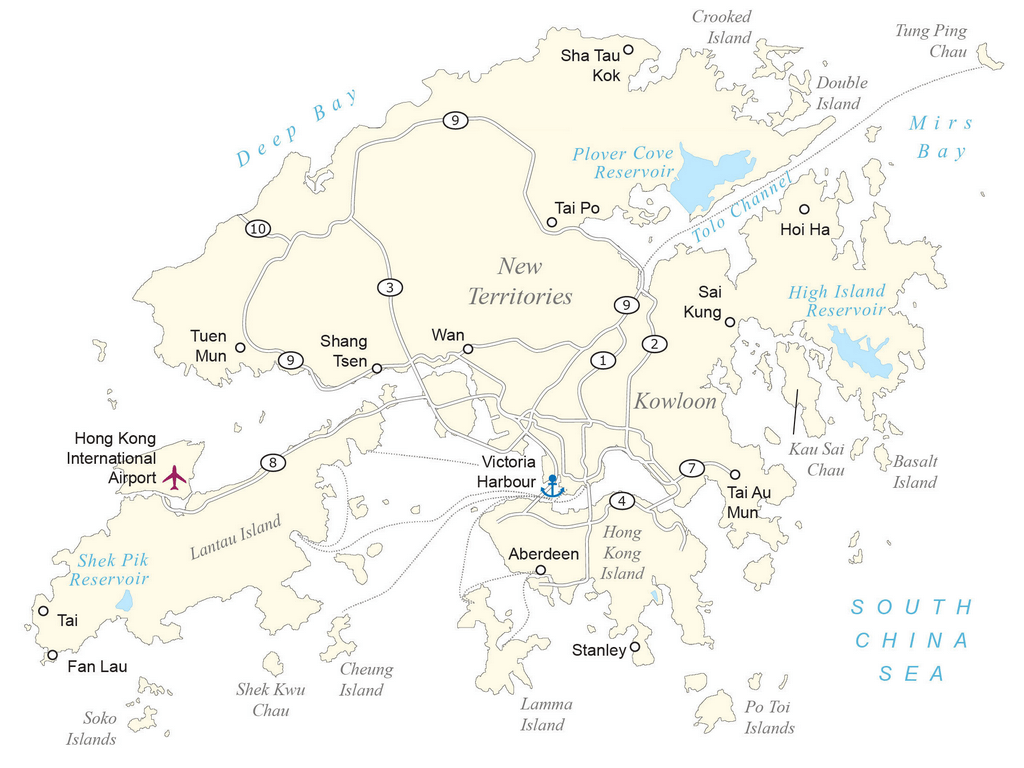

Hong Kong occupies a total area of 1,108 sq. km in the eastern Pearl River Delta of the South China Sea. As seen on the physical map of Hong Kong, it also has several offshore islands including Lantau Island (the largest one), Hong Kong Island, Lamma Island, Cheung Island, Po Toi Island, and others.

Almost all of the available land in Hong Kong is hilly to mountainous with steep slopes. There are very steep mountains that drop into the sea, with some exceeding 2,500 ft. (764 m).

The highest point in Hong Kong is Tai Mo Shan (marked on the map), whose summit peaks at 3,143 ft (958 m). It is located in Tsuen Wan in the New Territories.

Lowlands cover less than one-fifth of Hong Kong’s area. In the north, Yuen Long and Sheung Shui plains are the only regions featuring extensive lowlands.

The land is lower on the northern edges of Hong Kong Island, and in the north along the border with China.

The only major river is the Sham Chun which flows in the north of Hong Kong and drains into Deep Bay.

At 0 m, the South China Sea is the lowest elevation in Hong Kong.

Discover the Beauty of Hong Kong with this Map

Hong Kong is a stunning destination, full of fascinating places to explore. From the metropolitan area to the lush national parks, this map of Hong Kong reveals the beauty of this vibrant city. Take a look and discover the many wonders of this amazing city.

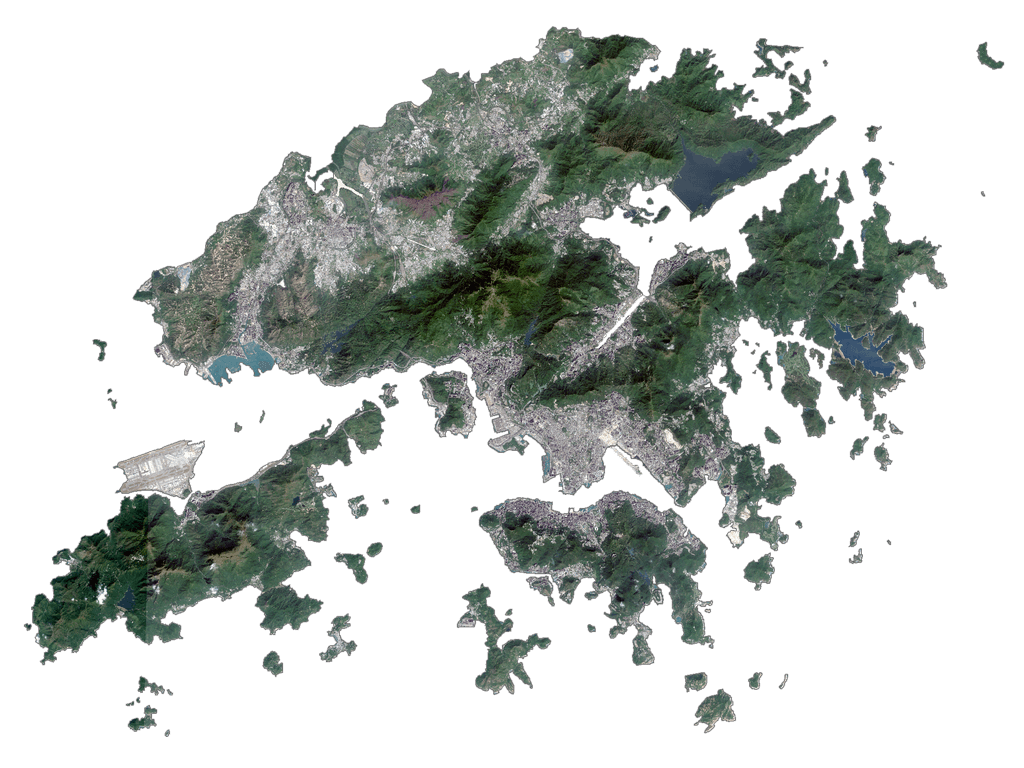

This map of Hong Kong displays the populated places, roads, islands, and districts of the city. With satellite imagery, you can get a glimpse of the metropolitan area and the various national parks of Hong Kong. Whether you’re planning a trip to this vibrant city or just looking to admire its beauty from afar, this map of Hong Kong is the perfect way to explore.

Online Interactive Political Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

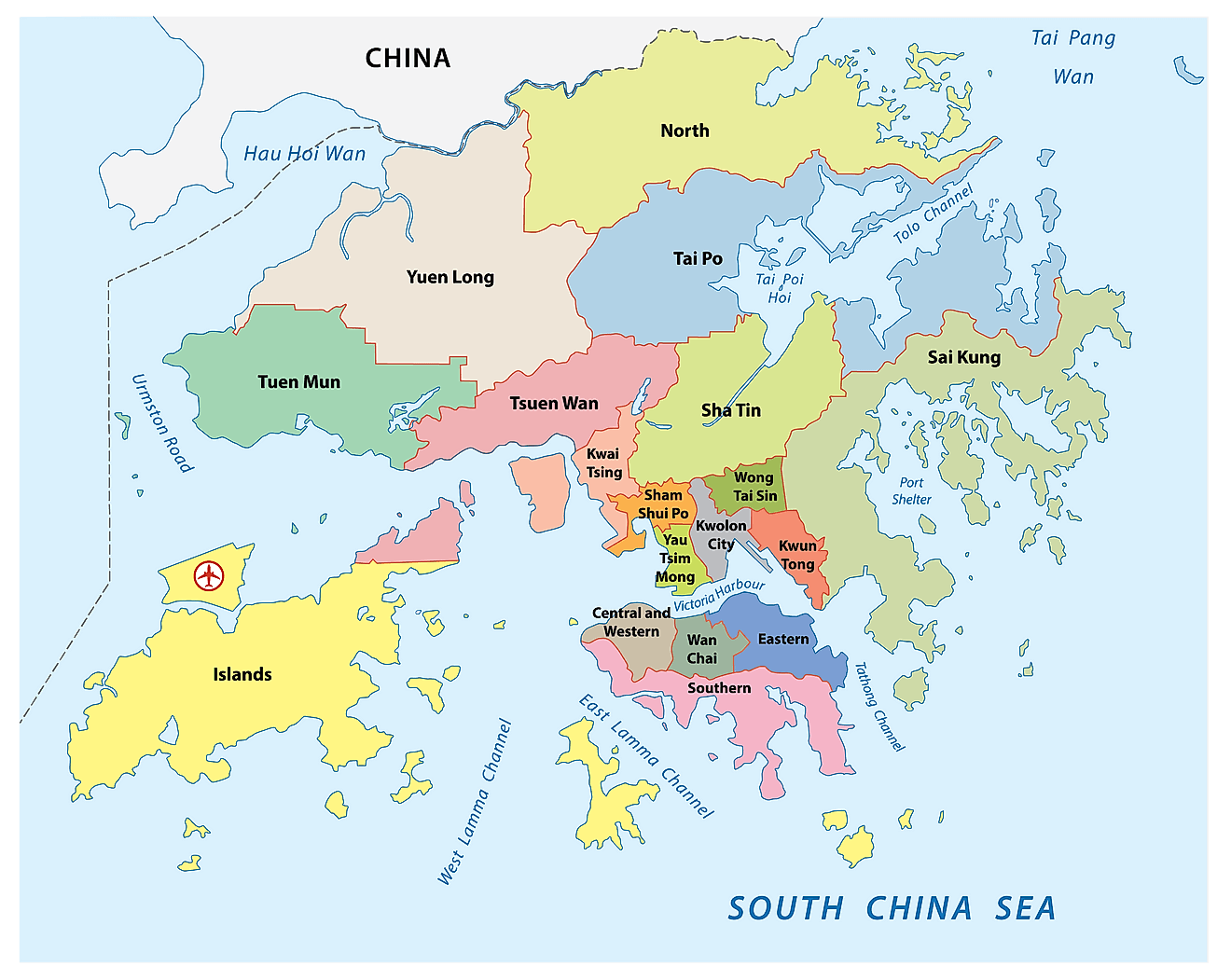

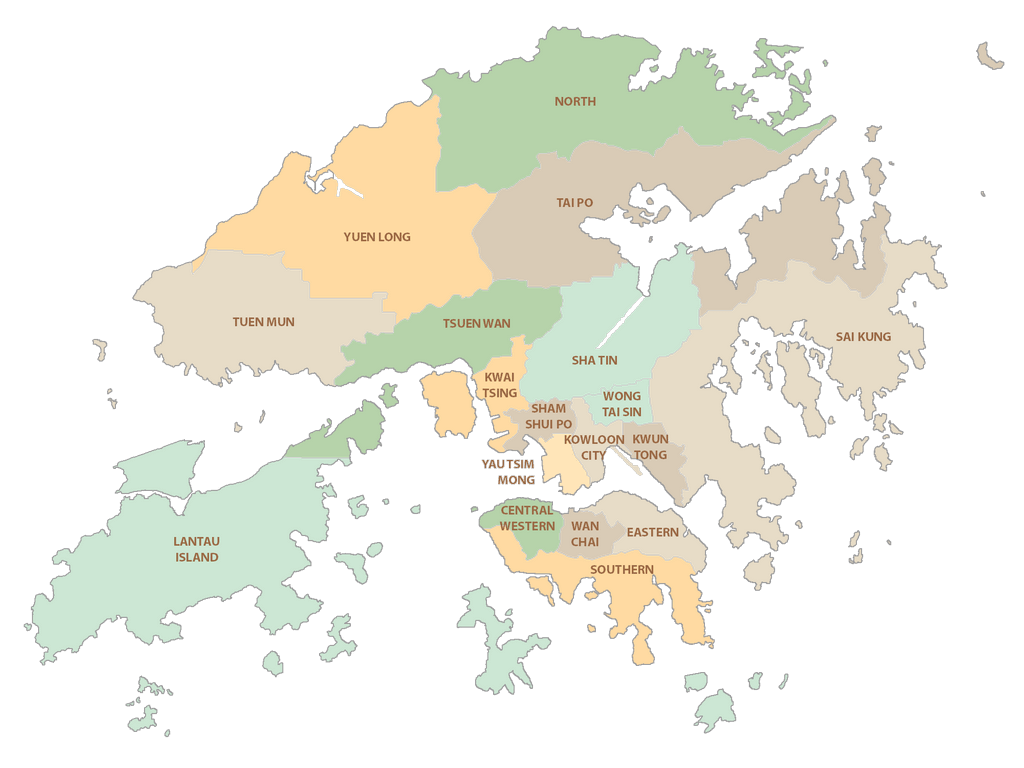

Hong Kong (officially, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China) is divided into 18 districts. These districts are: Islands, Kwai Tsing, North, Sai Kung, Sha Tin, Tai Po, Tsuen Wan, Tuen Mun, Yuen Long, Kowloon city, Kwun Tong, Sham Shui Po, Wong Tai Sin, Yau Tsim Mong, Central and Western, Eastern, Southern and Wan Chai.

With an area of 1,104 sq. km, and a population of over 7.5 million people, Hong Kong is one of the most densely populated regions of the world. Hong Kong is one of the world’s leading financial center and also the most significant economic and commercial ports.

Location Maps

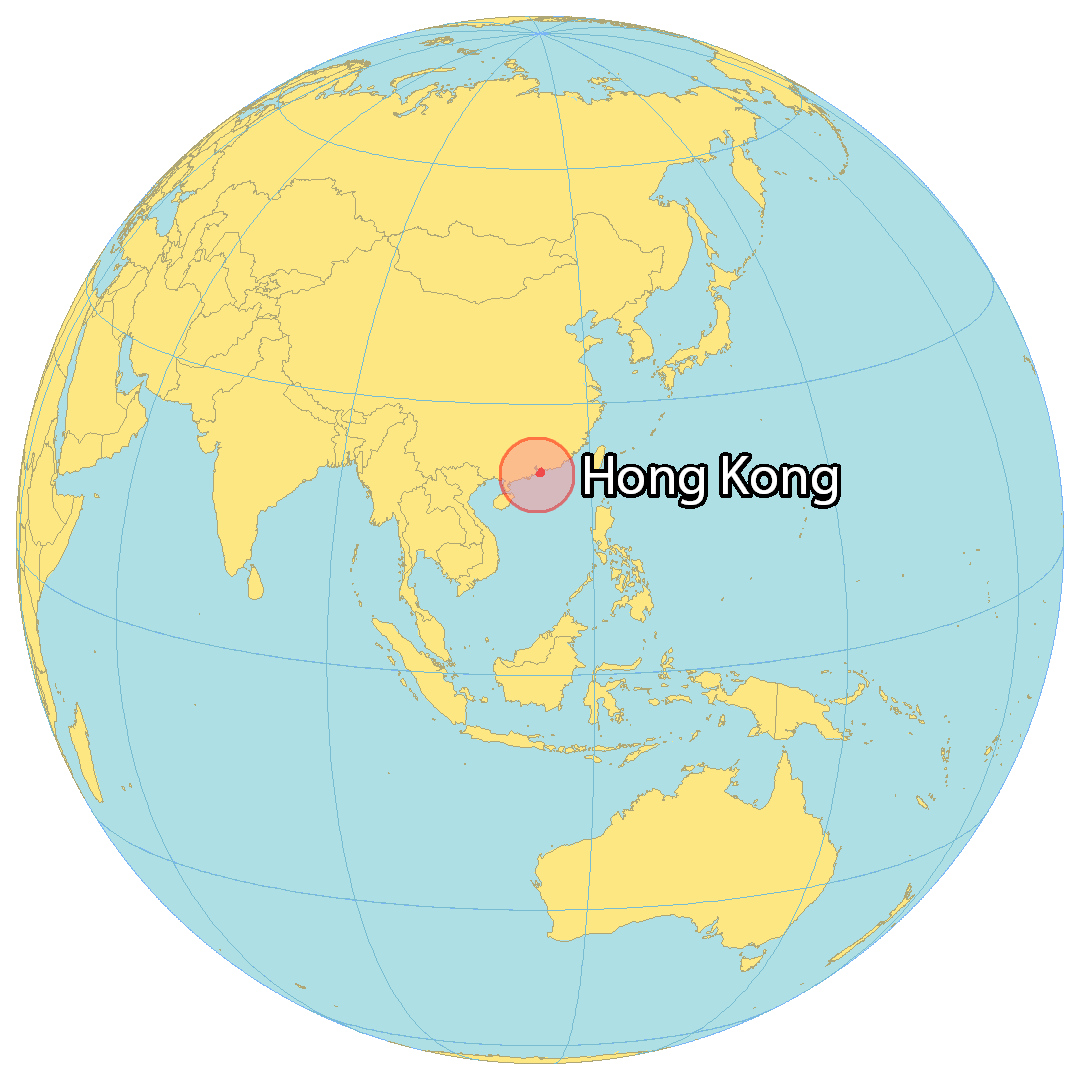

Where is Hong Kong?

Hong Kong is recognized as a “Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China”. It’s located on the south coast bordered by China in the north and near Macau to the east. Hong Kong is 2,755 square kilometers (1,064 sq mi) in area, about one-quarter the size of Rhode Island.

Hong Kong is home to over 7.5 million people. But it’s also known for being a center of business with more skyscrapers than even New York City. High rental costs have made Hong Kong one of the most expensive places to live in the world. Despite this, the city is still referred to as a “kaleidoscope of life” due to its unique blend of Eastern and Western cultures.

High Definition Political Map of Hong Kong

Hong Kong Administrative Map

History

Prehistory and Imperial China

Earliest known human traces in what is now Hong Kong are dated by some to 35,000 and 39,000 years ago during the Paleolithic period. The claim is based on an archaeological investigation in Wong Tei Tung, Sai Kung in 2003. The archaeological works revealed knapped stone tools from deposits that were dated using optical luminescence dating.

During the Middle Neolithic period, about 6,000 years ago, the region had been widely occupied by humans. Neolithic to Bronze Age Hong Kong settlers were semi-coastal people. Early inhabitants are believed to be Austronesians in the Middle Neolithic period and later the Yueh people. As hinted by the archaeological works in Sha Ha, Sai Kung, rice cultivation had been introduced since Late Neolithic period. Bronze Age Hong Kong featured coarse pottery, hard pottery, quartz and stone jewelry, as well as small bronze implements.

The Qin dynasty incorporated the Hong Kong area into China for the first time in 214 BCE, after conquering the indigenous Baiyue. The region was consolidated under the Nanyue kingdom (a predecessor state of Vietnam) after the Qin collapse and recaptured by China after the Han conquest. During the Mongol conquest of China in the 13th century, the Southern Song court was briefly located in modern-day Kowloon City (the Sung Wong Toi site) before its final defeat in the 1279 Battle of Yamen. By the end of the Yuan dynasty, seven large families had settled in the region and owned most of the land. Settlers from nearby provinces migrated to Kowloon throughout the Ming dynasty.

The earliest European visitor was Portuguese explorer Jorge Álvares, who arrived in 1513. Portuguese merchants established a trading post called Tamão in Hong Kong waters and began regular trade with southern China. Although the traders were expelled after military clashes in the 1520s, Portuguese-Chinese trade relations were re-established by 1549. Portugal acquired a permanent lease for Macau in 1557.

After the Qing conquest, maritime trade was banned under the Haijin policies. From 1661 to 1683, the population of most of the area forming present day Hong Kong was cleared under the Great Clearance, turning the region into a wasteland. The Kangxi Emperor lifted the maritime trade prohibition, allowing foreigners to enter Chinese ports in 1684. Qing authorities established the Canton System in 1757 to regulate trade more strictly, restricting non-Russian ships to the port of Canton. Although European demand for Chinese commodities like tea, silk, and porcelain was high, Chinese interest in European manufactured goods was insignificant, so that Chinese goods could only be bought with precious metals. To reduce the trade imbalance, the British sold large amounts of Indian opium to China. Faced with a drug crisis, Qing officials pursued ever more aggressive actions to halt the opium trade.

British colony

In 1839, the Daoguang Emperor rejected proposals to legalise and tax opium and ordered imperial commissioner Lin Zexu to eradicate the opium trade. The commissioner destroyed opium stockpiles and halted all foreign trade, triggering a British military response and the First Opium War. The Qing surrendered early in the war and ceded Hong Kong Island in the Convention of Chuenpi. British forces began controlling Hong Kong shortly after the signing of the convention, from 26 January 1841. However, both countries were dissatisfied and did not ratify the agreement. After more than a year of further hostilities, Hong Kong Island was formally ceded to the United Kingdom in the 1842 Treaty of Nanking.

Administrative infrastructure was quickly built by early 1842, but piracy, disease, and hostile Qing policies initially prevented the government from attracting commerce. Conditions on the island improved during the Taiping Rebellion in the 1850s, when many Chinese refugees, including wealthy merchants, fled mainland turbulence and settled in the colony. Further tensions between the British and Qing over the opium trade escalated into the Second Opium War. The Qing were again defeated and forced to give up Kowloon Peninsula and Stonecutters Island in the Convention of Peking. By the end of this war, Hong Kong had evolved from a transient colonial outpost into a major entrepôt. Rapid economic improvement during the 1850s attracted foreign investment, as potential stakeholders became more confident in Hong Kong’s future.

The colony was further expanded in 1898 when Britain obtained a 99-year lease of the New Territories. The University of Hong Kong was established in 1911 as the territory’s first institution of higher education. Kai Tak Airport began operation in 1924, and the colony avoided a prolonged economic downturn after the 1925–26 Canton–Hong Kong strike. At the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, Governor Geoffry Northcote declared Hong Kong a neutral zone to safeguard its status as a free port. The colonial government prepared for a possible attack, evacuating all British women and children in 1940. The Imperial Japanese Army attacked Hong Kong on 8 December 1941, the same morning as its attack on Pearl Harbor. Hong Kong was occupied by Japan for almost four years before Britain resumed control on 30 August 1945.

Its population rebounded quickly after the war, as skilled Chinese migrants fled from the Chinese Civil War and more refugees crossed the border when the Chinese Communist Party took control of mainland China in 1949. Hong Kong became the first of the Four Asian Tiger economies to industrialise during the 1950s. With a rapidly increasing population, the colonial government attempted reforms to improve infrastructure and public services. The public-housing estate programme, Independent Commission Against Corruption, and Mass Transit Railway were all established during the post-war decades to provide safer housing, integrity in the civil service, and more reliable transportation.

Nevertheless, widespread public discontent resulted in multiple protests from the 1950s to 1980s, including pro-Republic of China and pro-Chinese Communist Party protests. In the 1967 Hong Kong riots, pro-PRC protestors clashed with the British colonial government. As many as 51 were killed and 802 were injured in the violence, including dozens killed by the Royal Hong Kong Police via beatings and shootings.

Although the territory’s competitiveness in manufacturing gradually declined because of rising labour and property costs, it transitioned to a service-based economy. By the early 1990s, Hong Kong had established itself as a global financial centre and shipping hub.

Chinese special administrative region

The colony faced an uncertain future as the end of the New Territories lease approached, and Governor Murray MacLehose raised the question of Hong Kong’s status with Deng Xiaoping in 1979. Diplomatic negotiations with China resulted in the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration, in which the United Kingdom agreed to transfer the colony in 1997 and China would guarantee Hong Kong’s economic and political systems for 50 years after the transfer. The impending transfer triggered a wave of mass emigration as residents feared an erosion of civil rights, the rule of law, and quality of life. Over half a million people left the territory during the peak migration period, from 1987 to 1996. The Legislative Council became a fully elected legislature for the first time in 1995 and extensively expanded its functions and organisations throughout the last years of the colonial rule. Hong Kong was transferred to China on 1 July 1997, after 156 years of British rule.

Immediately after the transfer, Hong Kong was severely affected by several crises. The Hong Kong government was forced to use substantial foreign exchange reserves to maintain the Hong Kong dollar’s currency peg during the 1997 Asian financial crisis, and the recovery from this was muted by an H5N1 avian-flu outbreak and a housing surplus. This was followed by the 2003 SARS epidemic, during which the territory experienced its most serious economic downturn.

Political debates after the transfer of sovereignty have centred around the region’s democratic development and the Chinese central government’s adherence to the “one country, two systems” principle. After reversal of the last colonial era Legislative Council democratic reforms following the handover, the regional government unsuccessfully attempted to enact national security legislation pursuant to Article 23 of the Basic Law. The central government decision to implement nominee pre-screening before allowing chief executive elections triggered a series of protests in 2014 which became known as the Umbrella Revolution. Discrepancies in the electoral registry and disqualification of elected legislators after the 2016 Legislative Council elections and enforcement of national law in the West Kowloon high-speed railway station raised further concerns about the region’s autonomy. In June 2019, mass protests erupted in response to a proposed extradition amendment bill permitting the extradition of fugitives to mainland China. The protests are the largest in Hong Kong’s history, with organisers claiming to have attracted more than three million Hong Kong residents.

The Hong Kong regional government and Chinese central government responded to the protests with a number of administrative measures to quell dissent. In June 2020, the Legislative Council passed the National Anthem Ordinance, which criminalised “insults to the national anthem of China”. The Chinese central government meanwhile enacted the Hong Kong national security law to help quell protests in the region. Nine months later, in March 2021, the Chinese central government introduced amendments to Hong Kong’s electoral system, which included the reduction of directly elected seats in the Legislative Council and the requirement that all candidates be vetted and approved by a Beijing-appointed Candidate Eligibility Review Committee.

Physical Map of Hong Kong