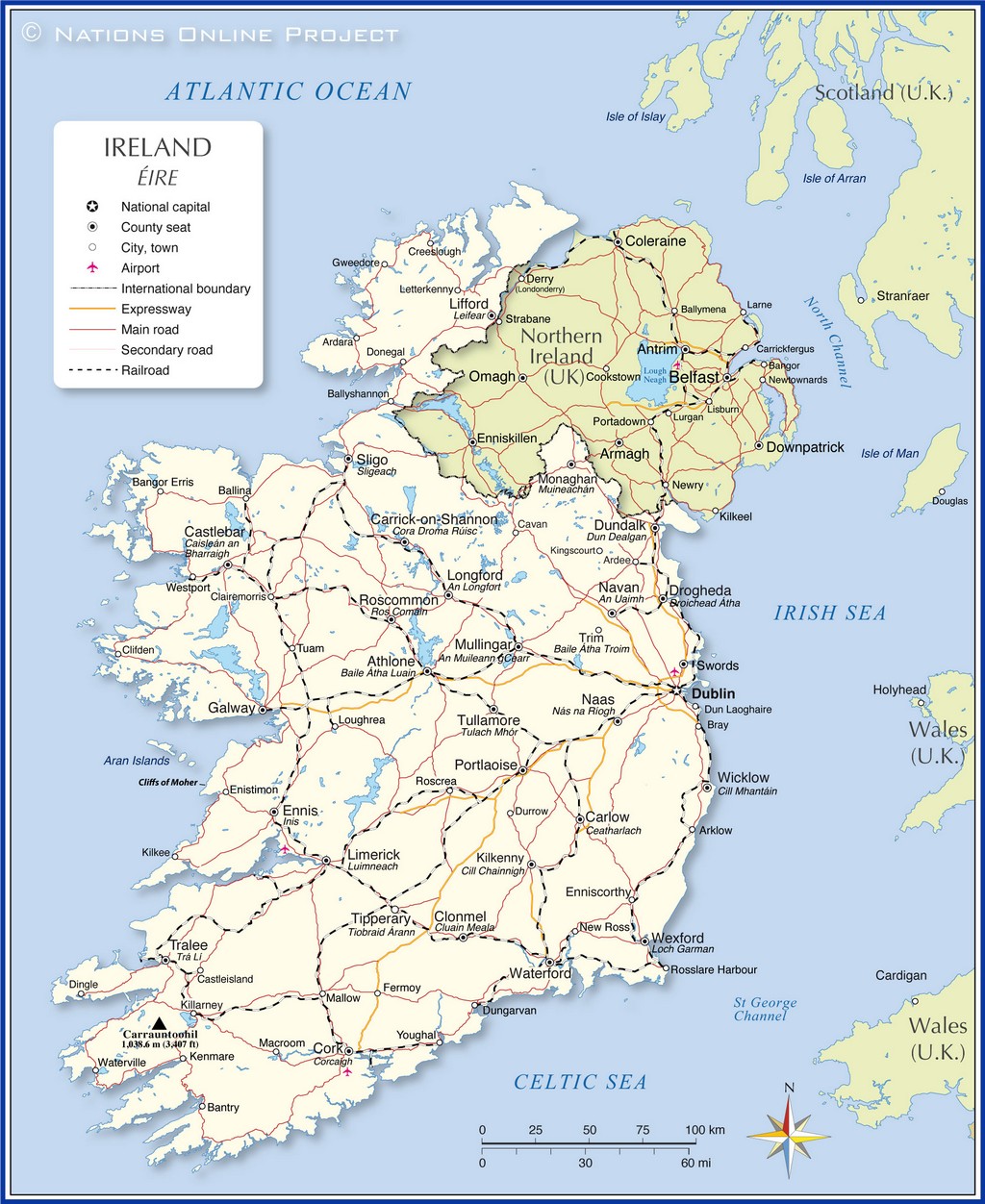

An island country in the North Atlantic, Ireland has an area of 84,421 km2 (32,595 sq mi). As observed on the physical map of Ireland above, the country has a significantly diverse topography despite its small size.

Ireland’s central lowlands of flat rolling plains are dissected by bogs, loughs (lakes) and rivers, and surrounded by hills and low mountains.

The major mountain ranges include the Blackstairs, Bluestack, Comeragh, Derryveagh, Macgillycuddy’s Reeks, Nephinbeg, Ox, Silvermines, Slieve Mish, Twelve Pins, and Wicklow.

The country’s highest point, Carrauntuohill, in the far southwest, stands at 1041 m (3414 ft.) high. The yellow upright triangle marks its position on the map.

The western coastline includes numerous sea cliffs. The most famous, and some say the most beautiful in all of Europe, are the Cliff of Moher. They reach a maximum height of just over 213 m (700 ft.)

As observed on the map above, Ireland has dozens of coastal islands, including Achill, the country’s largest. Others of significance include the Aran Islands to the southwest of Galway and Valentia Island just off the Iveragh Peninsula. Other peninsulas of note include the Beara and Dingle.

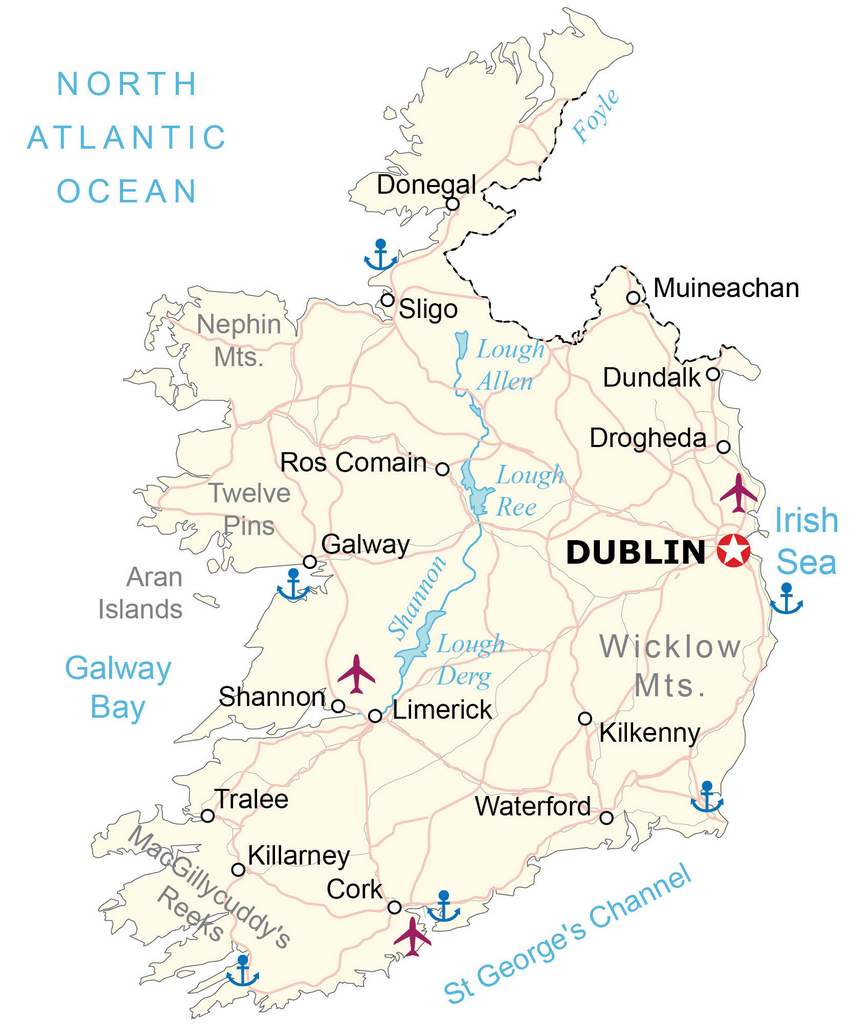

The River Shannon at 386 km (240 miles) long is Ireland’s longest river. It widens into four loughs (lakes) along its route, including Lough Allen, Lough Bafin, Lough Derg and Lough Ree. Other inland loughs of note are the Conn, Corrib and Mask.

Besides the Shannon, additional rivers of size are the Barrow, Blackwater, Boyne, Finn, Lee, Liffey, Nore, Slaney and Suir.

The lowest point of Ireland is the sea at 0 m.

Explore the Republic of Ireland and its varied landscape with this interactive map. Featuring major cities, highways, lakes, rivers, and airports, this map gives you a unique view of the country. Zoom in to see the elevation and satellite views of the Irish landscape, including its various mountain ranges.

Online Interactive Political Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

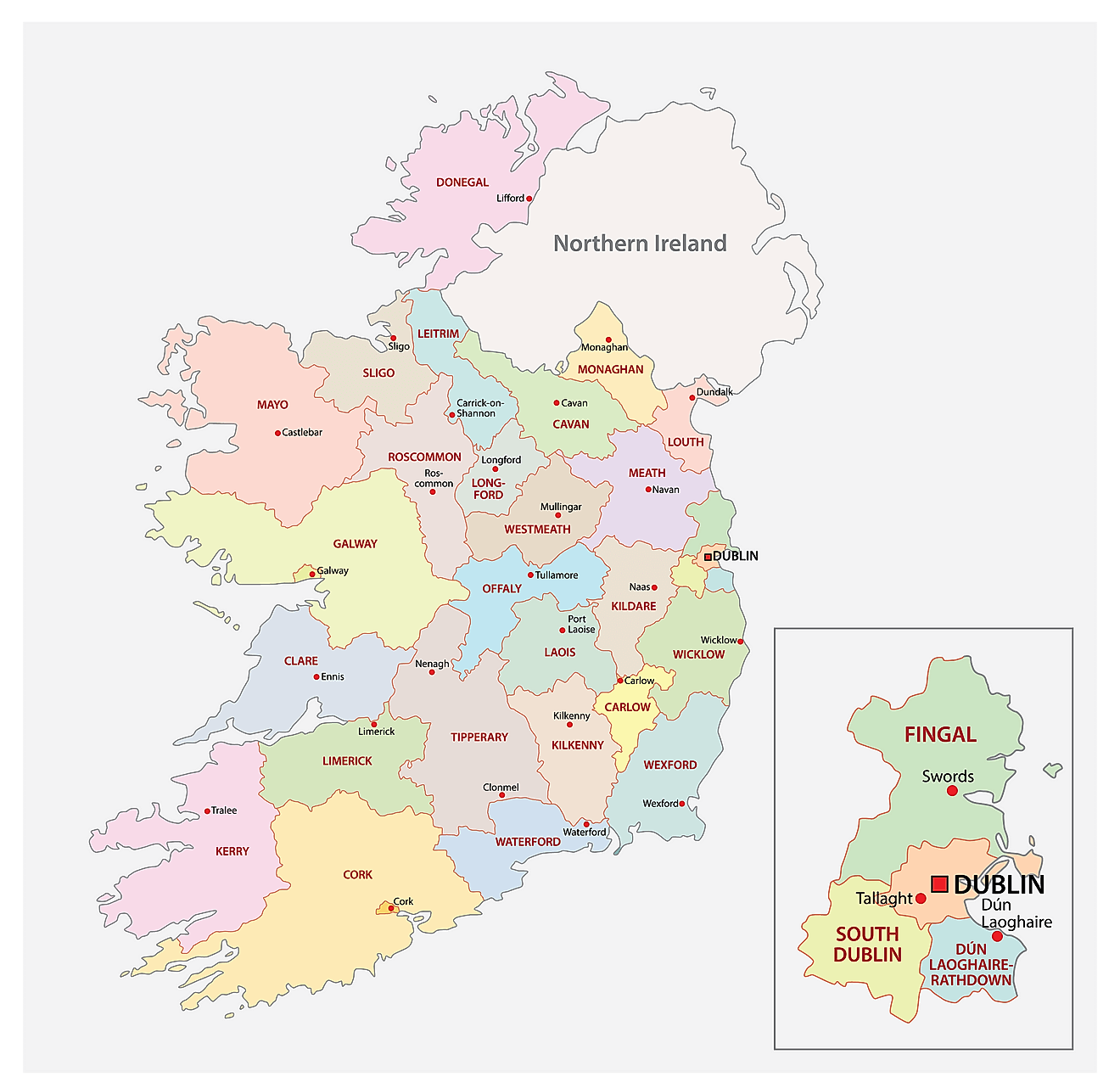

Ireland (officially, the Republic of Ireland) is divided into 26 county councils, 3 city councils, 2 city & county councils.

The county councils are: Carlow, Dun Laoghaire Rathdown, Fingal, South Dublin, Kildare, Kilkenny, Laois, Longford, Louth, Meath, Offaly, Westmeath, Wexford, Wicklow, Clare, Cork, Kerry, Tipperary, Galway, Leitrium, Mayo, Roscommon, Sligo, Cavan, Donegal and Monaghan.

The city councils are: Dublin city council, Cork city council and Galway city council.

The city and county councils are: Limerick city and county council, Waterford city and county council.

Located in the eastern part of the country is, Dublin – the capital, the largest and the most populous city in Ireland. It is also the major cultural, financial, commercial center and the chief maritime port of Ireland.

Location Maps

Where is Ireland?

The Republic of Ireland is situated on an island in Western Europe, along with Northern Ireland. It shares its eastern border with the Irish Sea, the southern border with the Celtic Sea, and is bordered by the North Atlantic Ocean to the west. St. George’s Channel lies between Ireland and Wales, both of which are part of the United Kingdom.

Dublin is the capital of Ireland, with 40% of the population living within 100 kilometers of the city. The other major cities in the country are Belfast, Cork, and Limerick.

High Definition Political Map of Ireland

History

Home-rule movement

From the Act of Union on 1 January 1801, until 6 December 1922, the island of Ireland was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. During the Great Famine, from 1845 to 1849, the island’s population of over 8 million fell by 30%. One million Irish died of starvation and/or disease and another 1.5 million emigrated, mostly to the United States. This set the pattern of emigration for the century to come, resulting in constant population decline up to the 1960s.

From 1874, and particularly under Charles Stewart Parnell from 1880, the Irish Parliamentary Party gained prominence. This was firstly through widespread agrarian agitation via the Irish Land League, which won land reforms for tenants in the form of the Irish Land Acts, and secondly through its attempts to achieve Home Rule, via two unsuccessful bills which would have granted Ireland limited national autonomy. These led to “grass-roots” control of national affairs, under the Local Government Act 1898, that had been in the hands of landlord-dominated grand juries of the Protestant Ascendancy.

Home Rule seemed certain when the Parliament Act 1911 abolished the veto of the House of Lords, and John Redmond secured the Third Home Rule Act in 1914. However, the Unionist movement had been growing since 1886 among Irish Protestants after the introduction of the first home rule bill, fearing discrimination and loss of economic and social privileges if Irish Catholics achieved real political power. In the late 19th and early 20th-century unionism was particularly strong in parts of Ulster, where industrialisation was more common in contrast to the more agrarian rest of the island, and where the Protestant population was more prominent, with a majority in four counties. Under the leadership of the Dublin-born Sir Edward Carson of the Irish Unionist Party and the Ulsterman Sir James Craig of the Ulster Unionist Party, unionists became strongly militant, forming Ulster Volunteers in order to oppose “the Coercion of Ulster”. After the Home Rule Bill passed parliament in May 1914, to avoid rebellion with Ulster, the British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith introduced an Amending Bill reluctantly conceded to by the Irish Party leadership. This provided for the temporary exclusion of Ulster from the workings of the bill for a trial period of six years, with an as yet undecided new set of measures to be introduced for the area to be temporarily excluded.

Revolution and steps to independence

Though it received the Royal Assent and was placed on the statute books in 1914, the implementation of the Third Home Rule Act was suspended until after the First World War which defused the threat of civil war in Ireland. With the hope of ensuring the implementation of the Act at the end of the war through Ireland’s engagement in the war, Redmond and the Irish National Volunteers supported the UK and its Allies. 175,000 men joined Irish regiments of the 10th (Irish) and 16th (Irish) divisions of the New British Army, while Unionists joined the 36th (Ulster) divisions.

The remainder of the Irish Volunteers, who refused Redmond and opposed any support of the UK, launched an armed insurrection against British rule in the 1916 Easter Rising, together with the Irish Citizen Army. This commenced on 24 April 1916 with the declaration of independence. After a week of heavy fighting, primarily in Dublin, the surviving rebels were forced to surrender their positions. The majority were imprisoned, with fifteen of the prisoners (including most of the leaders) were executed as traitors to the UK. This included Patrick Pearse, the spokesman for the rising and who provided the signal to the volunteers to start the rising, as well as James Connolly, socialist and founder of the Industrial Workers of the World union and both the Irish and Scottish Labour movements. These events, together with the Conscription Crisis of 1918, had a profound effect on changing public opinion in Ireland against the British Government.

In January 1919, after the December 1918 general election, 73 of Ireland’s 105 Members of Parliament (MPs) elected were Sinn Féin members who were elected on a platform of abstentionism from the British House of Commons. In January 1919, they set up an Irish parliament called Dáil Éireann. This first Dáil issued a declaration of independence and proclaimed an Irish Republic. The declaration was mainly a restatement of the 1916 Proclamation with the additional provision that Ireland was no longer a part of the United Kingdom. The Irish Republic’s Ministry of Dáil Éireann sent a delegation under Ceann Comhairle (Head of Council, or Speaker, of the Daíl) Seán T. O’Kelly to the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, but it was not admitted.

After the War of Independence and truce called in July 1921, representatives of the British government and the five Irish treaty delegates, led by Arthur Griffith, Robert Barton and Michael Collins, negotiated the Anglo-Irish Treaty in London from 11 October to 6 December 1921. The Irish delegates set up headquarters at Hans Place in Knightsbridge, and it was here in private discussions that the decision was taken on 5 December to recommend the treaty to Dáil Éireann. On 7 January 1922, the Second Dáil ratified the Treaty by 64 votes to 57.

In accordance with the treaty, on 6 December 1922 the entire island of Ireland became a self-governing Dominion called the Irish Free State (Saorstát Éireann). Under the Constitution of the Irish Free State, the Parliament of Northern Ireland had the option to leave the Irish Free State one month later and return to the United Kingdom. During the intervening period, the powers of the Parliament of the Irish Free State and Executive Council of the Irish Free State did not extend to Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland exercised its right under the treaty to leave the new Dominion and rejoined the United Kingdom on 8 December 1922. It did so by making an address to the King requesting, “that the powers of the Parliament and Government of the Irish Free State shall no longer extend to Northern Ireland.” The Irish Free State was a constitutional monarchy sharing a monarch with the United Kingdom and other Dominions of the British Commonwealth. The country had a governor-general (representing the monarch), a bicameral parliament, a cabinet called the “Executive Council”, and a prime minister called the President of the Executive Council.

Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War (June 1922 – May 1923) was the consequence of the ratification of the Anglo-Irish Treaty and the creation of the Irish Free State. Anti-treaty forces, led by Éamon de Valera, objected to the fact that acceptance of the treaty abolished the Irish Republic of 1919 to which they had sworn loyalty, arguing in the face of public support for the settlement that the “people have no right to do wrong”. They objected most to the fact that the state would remain part of the British Empire and that members of the Free State Parliament would have to swear what the anti-treaty side saw as an oath of fidelity to the British king. Pro-treaty forces, led by Michael Collins, argued that the treaty gave “not the ultimate freedom that all nations aspire to and develop, but the freedom to achieve it”.

At the start of the war, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) split into two opposing camps: a pro-treaty IRA and an anti-treaty IRA. The pro-treaty IRA disbanded and joined the new National Army. However, because the anti-treaty IRA lacked an effective command structure and because of the pro-treaty forces’ defensive tactics throughout the war, Michael Collins and his pro-treaty forces were able to build up an army with many tens of thousands of World War I veterans from the 1922 disbanded Irish regiments of the British Army, capable of overwhelming the anti-treatyists. British supplies of artillery, aircraft, machine-guns and ammunition boosted pro-treaty forces, and the threat of a return of Crown forces to the Free State removed any doubts about the necessity of enforcing the treaty. Lack of public support for the anti-treaty forces (often called the Irregulars) and the determination of the government to overcome the Irregulars contributed significantly to their defeat.

Constitution of Ireland 1937

Following a national plebiscite in July 1937, the new Constitution of Ireland (Bunreacht na hÉireann) came into force on 29 December 1937. This replaced the Constitution of the Irish Free State and declared that the name of the state is Éire, or “Ireland” in the English language. While Articles 2 and 3 of the Constitution defined the national territory to be the whole island, they also confined the state’s jurisdiction to the area that had been the Irish Free State. The former Irish Free State government had abolished the Office of Governor-General in December 1936. Although the constitution established the office of President of Ireland, the question over whether Ireland was a republic remained open. Diplomats were accredited to the king, but the president exercised all internal functions of a head of state. For instance, the President gave assent to new laws with his own authority, without reference to King George VI who was only an “organ”, that was provided for by statute law.

Ireland remained neutral during World War II, a period it described as The Emergency. Ireland’s Dominion status was terminated with the passage of the Republic of Ireland Act 1948, which came into force on 18 April 1949 and declared that the state was a republic. At the time, a declaration of a republic terminated Commonwealth membership. This rule was changed 10 days after Ireland declared itself a republic, with the London Declaration of 28 April 1949. Ireland did not reapply when the rules were altered to permit republics to join. Later, the Crown of Ireland Act 1542 was repealed in Ireland by the Statute Law Revision (Pre-Union Irish Statutes) Act 1962.

Recent history

Ireland became a member of the United Nations in December 1955, after having been denied membership because of its neutral stance during the Second World War and not supporting the Allied cause. At the time, joining the UN involved a commitment to using force to deter aggression by one state against another if the UN thought it was necessary.

Interest towards membership of the European Communities (EC) developed in Ireland during the 1950s, with consideration also given to membership of the European Free Trade Area. As the United Kingdom intended on EC membership, Ireland applied for membership in July 1961 due to the substantial economic linkages with the United Kingdom. However, the founding EC members remained sceptical regarding Ireland’s economic capacity, neutrality, and unattractive protectionist policy. Many Irish economists and politicians realised that economic policy reform was necessary. The prospect of EC membership became doubtful in 1963 when French President General Charles de Gaulle stated that France opposed Britain’s accession, which ceased negotiations with all other candidate countries. However, in 1969 his successor, Georges Pompidou, was not opposed to British and Irish membership. Negotiations began and in 1972 the Treaty of Accession was signed. A referendum was held later that year which confirmed Ireland’s entry into the bloc, and it finally joined the EC as a member state on 1 January 1973.

The economic crisis of the late 1970s was fuelled by the Fianna Fáil government’s budget, the abolition of the car tax, excessive borrowing, and global economic instability including the 1979 oil crisis. There were significant policy changes from 1989 onwards, with economic reform, tax cuts, welfare reform, an increase in competition, and a ban on borrowing to fund current spending. This policy began in 1989–1992 by the Fianna Fáil/Progressive Democrat government, and continued by the subsequent Fianna Fáil/Labour government and Fine Gael/Labour/Democratic Left government. Ireland became one of the world’s fastest growing economies by the late 1990s in what was known as the Celtic Tiger period, which lasted until the Great Recession. However, since 2014, Ireland has experienced increased economic activity.

In the Northern Ireland question, the British and Irish governments started to seek a peaceful resolution to the violent conflict involving many paramilitaries and the British Army in Northern Ireland known as “The Troubles”. A peace settlement for Northern Ireland, known as the Good Friday Agreement, was approved in 1998 in referendums north and south of the border. As part of the peace settlement, the territorial claim to Northern Ireland in Articles 2 and 3 of the Constitution of Ireland was removed by referendum. In its white paper on Brexit the United Kingdom government reiterated its commitment to the Good Friday Agreement. With regard to Northern Ireland’s status, it said that the UK Government’s “clearly-stated preference is to retain Northern Ireland’s current constitutional position: as part of the UK, but with strong links to Ireland”.